Assessment of the Sharing Economy in the Context of Smart Cities: Social Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sharing Economy and the Potential of Its Application in the Social Sphere

2.1. Sharing Economy: The Origins of the Formation and Distribution

2.2. The Sharing Economy in Terms of Its Social Significance

2.3. Approaches to Measuring the Sharing Economy

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

- -

- indicator that characterises the degree of the consent of citizens with the fact that “bicycle hiring has reduced congestion” (X1);

- -

- an indicator that characterises the degree of the consent of citizens with the fact that “car-sharing Apps have reduced congestion” (X2);

- -

- an indicator that characterises the degree of the consent of citizens with the fact that “a website or App allows to give away unwanted items to other city residents” (X3).

3.2. Methodology for Assessing the Sharing Economy

4. Results

4.1. The Potential of Sharing Economy Services in Solving Social Problems

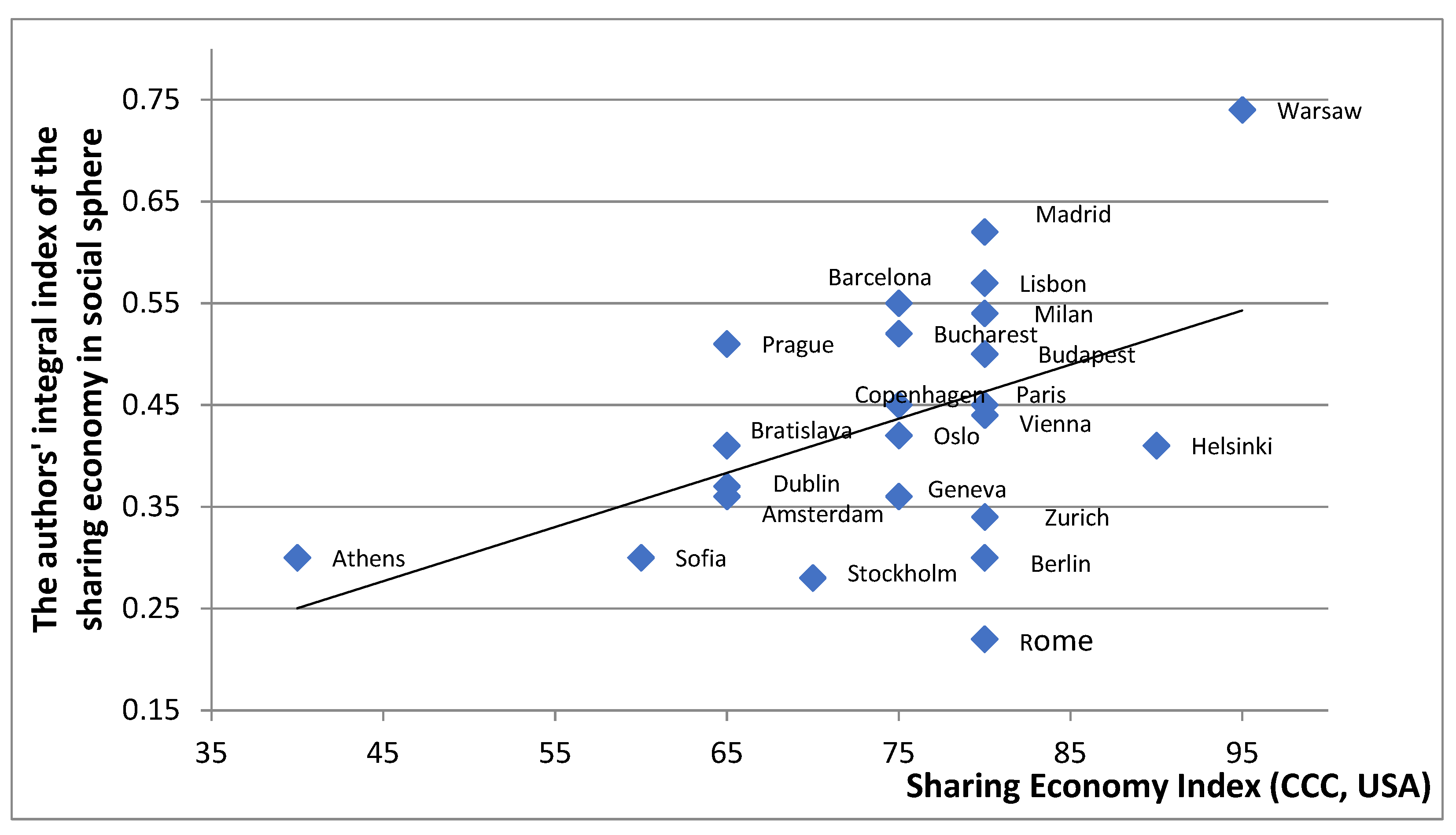

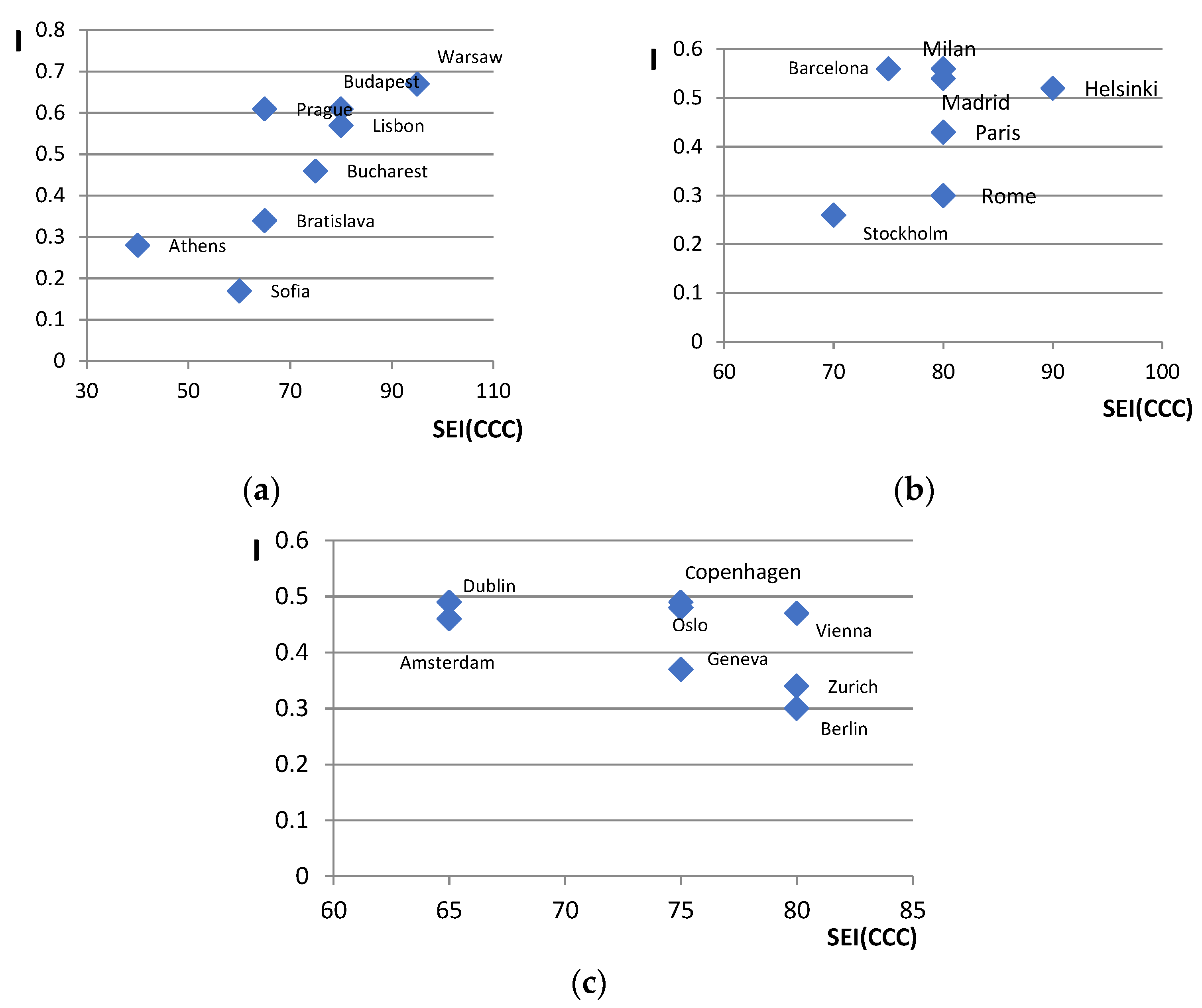

4.2. Ranking of Sharing Economy Cities

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mi, Z.; Coffman, D. The sharing economy promotes sustainable societies. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djevojić, C.; Brajak, M.; Mihajlovic, I. Transformation, Sharing Economy and Effects on Society. In Proceedings of the 32nd International DAAAM Symposium, Vienna, Austria, 28–29 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlitschek, F.; Teubner, T.; Gimpel, H. Consumer motives for peer-to-peer sharing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbis, N.; Soraperra, I.; Shalvi, S. The Consequences of Participating in the Sharing Economy: A Transparency-Based Sharing Framework. J. Manag. 2020, 47, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, E.; Hercegová, K.; Semyachkov, K. Innovations in the Institutional Modelling of the Sharing Economy. J. Inst. Stud. 2018, 10, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambovceva, T. Consumer Perception of Sharing Economy, Environmental Studies. Scholarly Community Encyclopedia. 2022. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17929 (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Ganapati, S.; Reddick, C.G. Prospects and challenges of sharing economy for the public sector. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Lin, Y.; Hou, H. What drives consumers to adopt a sharing platform: An integrated model of value-based and transaction cost theories. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, M. Collaborative consumption practices in Southeast Asian cities: Prospects for growth and sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, M.; Spaeth, J.L. Community Structure and Collaborative Consumption: A routine activity approach. Am. Behav. Sci. 1978, 21, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, A. Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure; Ronald Press: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Lessig, L. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; 329p. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; HarperBusiness: New York, NY, USA, 2010; 304p. [Google Scholar]

- The Sharing Economy. Consumer Intelligence Series; PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://eco.nomia.pt/contents/documentacao/pwc-cis-sharing-economy-1-2187.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Liu, C.; Chan, R.; Wang, M.; Yang, Z. Mapping the Sharing Economy in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Schraven, D.; Bocken, N.; Frenken, K.; Hekkert, M.; Kirchherr, J. The battle of the buzzwords: A comparative review of the circular economy and the sharing economy concepts. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanholz, J.; Leipold, S. Sharing for a circular economy? An analysis of digital sharing platforms’ principles and business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Jiang, J.; Li, E.Y. IT-based entrepreneurship in sharing economy: The mediating role of value expectancy in micro-entrepreneur’s passion and persistence. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Chang. Manag. 2018, 10, 352–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A.-V.; Valkama, P.; Bailey, S.J. Smart cities in the new service economy: Building platforms for smart services. AI Soc. 2013, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vith, S.; Oberg, A.; Höllerer, M.A.; Meyer, R.E. Envisioning the “sharing city”: Governance strategies for the sharing economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1023–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.T.; Kong, H.; Wu, R.; Sui, Z.D. Ridesourcing, the sharing economy, and the future of cities. Cities 2018, 76, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzaru, F.M.; Mitan, A.; Mihalcea, A.D. Reshaping Competition in the o Age of Platforms: The Winners of the Sharing Economy. In Knowledge Management in the Sharing Economy. Knowledge Management and Organizational Learning; Vätämänescu, E., Pinzaru, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turi, A.N.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Sánchez, D.; Osmani, D. A co-utility approach to the mesh economy: The crowd-based business model. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 11, 411–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.; Manjon, M.; Crutzen, N. Factors for collaboration amongst smart city stakeholders: A local government perspective. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbro.se. Timbro Sharing Economy Index. Available online: https://timbro.se/app/uploads/2018/07/tsei-version-17_web.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Sharing Economy Index 2020. Available online: https://consumerchoicecenter.org/sharing-economy-index-2021 (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Pepić, L. The sharing economy: Uber and its effect on taxi companies. Acta Econ. 2018, 16, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittel, A. Qualities of sharing and their transformations in the digital age. Int. Rev. Inf. Ethics 2011, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. Platform-based mechanisms, institutional trust, and continuous use intention: The moderating role of perceived effectiveness of sharing economy institutional mechanisms. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansky, L. The Mesh: Why the Future of Business Is Sharing; Portfolio Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberton, C.; Rose, R. When is ours better that mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. J. Mark. 2012, 4, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O. Clarifying the concept of Product-Service System. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G. Access based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquier, A.; Daudigeos, T.; Pinkse, J. Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, C.; Sandström, C. The sharing economy in social media—Analyzing tensions between market and non-market logics. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, B.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hamann, R.; Faccer, K. Upsides and downsides of the sharing economy: Collaborative consumption business models’ stakeholder value impacts and their relationship to context. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyader, H.; Piscicelli, L. Business model diversification in the sharing economy: The case of GoMore. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Sharing versus Pseudo-Sharing in Web 2.0. Anthropologist 2014, 1, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems, Prize Lecture. 8 December 2009. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/ostrom_lecture.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Williamson, O. Transaction Cost Economics: The Natural Progression. Prize Lecture. 8 December 2009. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/williamson_lecture.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Rochet, J.-C.; Tirole, J. Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2003, 1, 990–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, A.; Plenk, M.; Haselwander, M. Sharing Economy in the Financial Industry: A Platform Approach towards Sharing in Regulatory Reporting using the Shapley Value. SUERF Policy Note 2021, 225, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, T. The Sharing Economy: Business Cases of Social Enterprises Using Collaborative Networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 91, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battino, S.; Lampreu, S. The role of the sharing economy for a sustainable and innovative development of rural areas: A case study in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, A.I. The importance of the sharing economy in improving the quality of life and social integration of local communities on the example of virtual groups. Land 2021, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposato, P.; Preka, R.; Cappellaro, F.; Cutaia, L. Sharing economy and circular economy. How technology and collaborative consumption innovations boost closing the loop strategies. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Rong, K.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T. Value Co-creation for sustainable consumption and production in the sharing economy in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.; Pesonen, J. Impacts of Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Use on Travel Patterns. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, B.; Wattal, S. Show Me the Way to Go Home: An Empirical Investigation of Ride-Sharing and Alcohol Related Motor Vehicle Fatalities. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirta, S. Impact of carsharing on the mobility of lower-income populations in California. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 24, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenti, R.; Singh, J.; Cotrim, J.; Toni, M.; Sinha, R. Characterizing the sharing economy state of the research: A systematic map. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MD-SUTD Smart City Index Report, The IMD World Competitiveness Center. Available online: https://www.imd.org/research-knowledge/reports/imd-smart-city-index-2019/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Collaborative Economy Platforms. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tour_ce_omr/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicka, K. Technology Selection Using the TOPSIS Method. Foresight STI Gov. 2020, 1, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobkova, E. Assessment of the impact of socio-economic criteria on the sustainability of the development of the territory by the TOPSIS method. Reg. Econ. Theory Pract. 2020, 1, 84–107. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trends and Perspectives for Pallets and Wooden Packaging. In Proceedings of the Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Forests and the Forest Industry Seventy-Fourth Session, Geneva, Switzerland, 18–20 October 2016; Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/timber/meetings/20161018/E/ECE_TIM_2016_6_FINAL_wooden_packaging.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Acquier, A.; Carbone, V. Sharing economy and social innovation. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Law of the Sharing Economy; Nestor, M., Davidson, M., Finck, J., Infranca, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J. Debating the Sharing Economy, Great Transition Initiative Essay: Toward a Transformative Vision and Praxis. 2014. Available online: https://greattransition.org/publication/debating-the-sharing-economy (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Herrmann-Fankhaenel, A.; Huesig, S. How much social innovation is behind the online platforms of the sharing economy? An exploratory investigation and educing of clusters in the German context. In Proceedings of the Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), Honolulu, HI, USA, 4–8 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

| The Value of the Integral Index (I) | The City’s Position in the Ranking | Deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | I | Ranking |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3–2 | 5–4 |

| Krakow | 0.81 | 0.77 | 1 | 1 | –0.05 | 0 |

| Warsaw | 0.67 | 0.74 | 2 | 2 | 0.06 | 0 |

| Prague | 0.61 | 0.51 | 3 | 10 | –0.10 | 7 |

| Budapest | 0.61 | 0.50 | 4 | 11 | –0.10 | 7 |

| Lisbon | 0.57 | 0.57 | 5 | 4 | 0.00 | –1 |

| Bologna | 0.57 | 0.55 | 6 | 6 | –0.02 | 0 |

| Barcelona | 0.56 | 0.55 | 7 | 5 | –0.01 | –2 |

| Milan | 0.56 | 0.54 | 8 | 7 | –0.02 | –1 |

| Madrid | 0.54 | 0.62 | 9 | 3 | 0.07 | –6 |

| Helsinki | 0.52 | 0.41 | 10 | 17 | –0.11 | 7 |

| Copenhagen | 0.49 | 0.45 | 11 | 14 | –0.04 | 3 |

| Dublin | 0.49 | 0.36 | 12 | 20 | –0.13 | 8 |

| Oslo | 0.48 | 0.42 | 13 | 16 | –0.06 | 3 |

| Vienna | 0.47 | 0.44 | 14 | 15 | –0.03 | 1 |

| Bilbao | 0.47 | 0.48 | 15 | 12 | 0.01 | –3 |

| Lyon | 0.46 | 0.52 | 16 | 9 | 0.06 | –7 |

| Amsterdam | 0.46 | 0.37 | 17 | 19 | –0.09 | 2 |

| Bucharest | 0.46 | 0.52 | 18 | 8 | 0.07 | –10 |

| Paris | 0.43 | 0.45 | 19 | 13 | 0.02 | –6 |

| Geneva | 0.37 | 0.36 | 20 | 21 | –0.02 | 1 |

| Zaragoza | 0.34 | 0.34 | 21 | 22 | 0.00 | 1 |

| Bratislava | 0.34 | 0.41 | 22 | 18 | 0.07 | –4 |

| Zurich | 0.34 | 0.34 | 23 | 23 | 0.00 | 0 |

| Rome | 0.30 | 0.22 | 24 | 30 | –0.08 | 6 |

| Berlin | 0.30 | 0.30 | 25 | 25 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Hannover | 0.29 | 0.26 | 26 | 28 | –0.03 | 2 |

| Athens | 0.28 | 0.30 | 27 | 24 | 0.02 | –3 |

| Gothenburg | 0.27 | 0.16 | 28 | 31 | –0.10 | 3 |

| Stockholm | 0.26 | 0.28 | 29 | 27 | 0.02 | –2 |

| Rotterdam | 0.22 | 0.22 | 30 | 29 | 0.00 | –1 |

| Sofia | 0.17 | 0.30 | 31 | 26 | 0.12 | –5 |

| Indicators | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of nights per capita booked through the collaborative economy platform(X4) | 0.68 | 0.61 |

| Indicator characterising the degree of the consent of citizens with the statement that “car-sharing Apps have reduced congestion” (X2) | 0.73 | 0.84 |

| Indicator characterising the degree of the consent of citizens with the statement that “bicycle hiring has reduced congestion” (X1) | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| The indicator that characterises the degree of the consent of citizens with the statement that “a website or App allows unwanted items to be given away other city residents (X3)” | 0.36 | 0.27 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Veretennikova, A.; Kozinskaya, K. Assessment of the Sharing Economy in the Context of Smart Cities: Social Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912200

Veretennikova A, Kozinskaya K. Assessment of the Sharing Economy in the Context of Smart Cities: Social Performance. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912200

Chicago/Turabian StyleVeretennikova, Anna, and Kseniya Kozinskaya. 2022. "Assessment of the Sharing Economy in the Context of Smart Cities: Social Performance" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912200

APA StyleVeretennikova, A., & Kozinskaya, K. (2022). Assessment of the Sharing Economy in the Context of Smart Cities: Social Performance. Sustainability, 14(19), 12200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912200