2. Literature Review

In the application research of machine learning in mental health, Senders et al. believed that machine learning is the process of automatically analyzing or predicting new and unknown data by discovering the laws of many existing data points and information [

7]. The father of machine learning, TOM M. Mitchell, gave a formal definition of machine learning. Suppose that Performance (P) is used to evaluate the performance of a computer program on a certain task (T). If the program uses Experience (E) to improve the performance of T, that is, the improvement of P, the program mainly learns T. Many scholars have tried to use machine learning to predict complex psychological problems of individuals, such as predicting stress disorders and anxiety disorders [

8]. Chu and Yang found that thousands of effective features can only predict the possibility of suicide. They built a suicide recognizer for Weibo social media using a multi-layer perceptron algorithm, which can evaluate the possibility of the suicide of Weibo users in real-time with a prediction accuracy of about 94% [

9]. The survey of Aldahiri et al. used the data of 40,736 older people from different regions and used the existing diagnostic codes through machine learning. The future of Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly was predicted. In the following year, the predicted performance could reach 75% or higher [

10]. Kassab et al. used four different machine learning algorithms and multiple logistic regression models to predict the treatment effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy on children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The results showed that the machine learning algorithm performed well in children’s psychological prediction, with an average accuracy of about 80%. The best predictors of treatment effectiveness are the onset and duration of mental illness [

11].

The sports field has begun to try to use internet technology to monitor various physiological parameters of the human body in real-time. Ferrag et al. found that the instrumentation required in this type of field usually requires high experimental conditions and is expensive. In sports and health, the application of internet technology to health development has initially formed a certain influence. In the current information and communication technology, intelligent perception technology is an emerging technology. Fitness products such as smartphones and various wearable smart bracelets, such as sensors and GPS on smartphones, can monitor and guide ordinary people’s exercise [

12]. Jim et al. built a health counseling system based on wearable sensors. Portable and lightweight sensors allow users to obtain more precise motion monitoring [

13]. The results of Lee et al. on the effect of internet technology on mental health can provide a useful reference for college physical education teachers to guide extracurricular sports activities. Wearable smartphones can be used to obtain information conveniently and quickly, such as the user’s geographic location, exercise status, time, and physiological indicators [

14]. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, big data, and other related technologies can be used to analyze and process the user’s basic data and the data collected by the sensor, which can evaluate the user’s action status and guide the action correctly [

15].

Beverly pointed out that moral decision-making can be a responsive decision in the context of either a real or hypothetical moral dilemma (when a responsive choice is required, accompanied by certain moral rules or principles). It can be a morally acceptable decision about behavior judgments of sexuality or the moral character of others (including judgments about individuals, groups, or institutions) [

16]. Desioli et al. believed that the current research on moral science tends to understand the intrinsic nature of human morality from a broader perspective, and carries out more process research from the aspects of moral evolutionary bases, how to make moral decisions, and the construction and maintenance of norms [

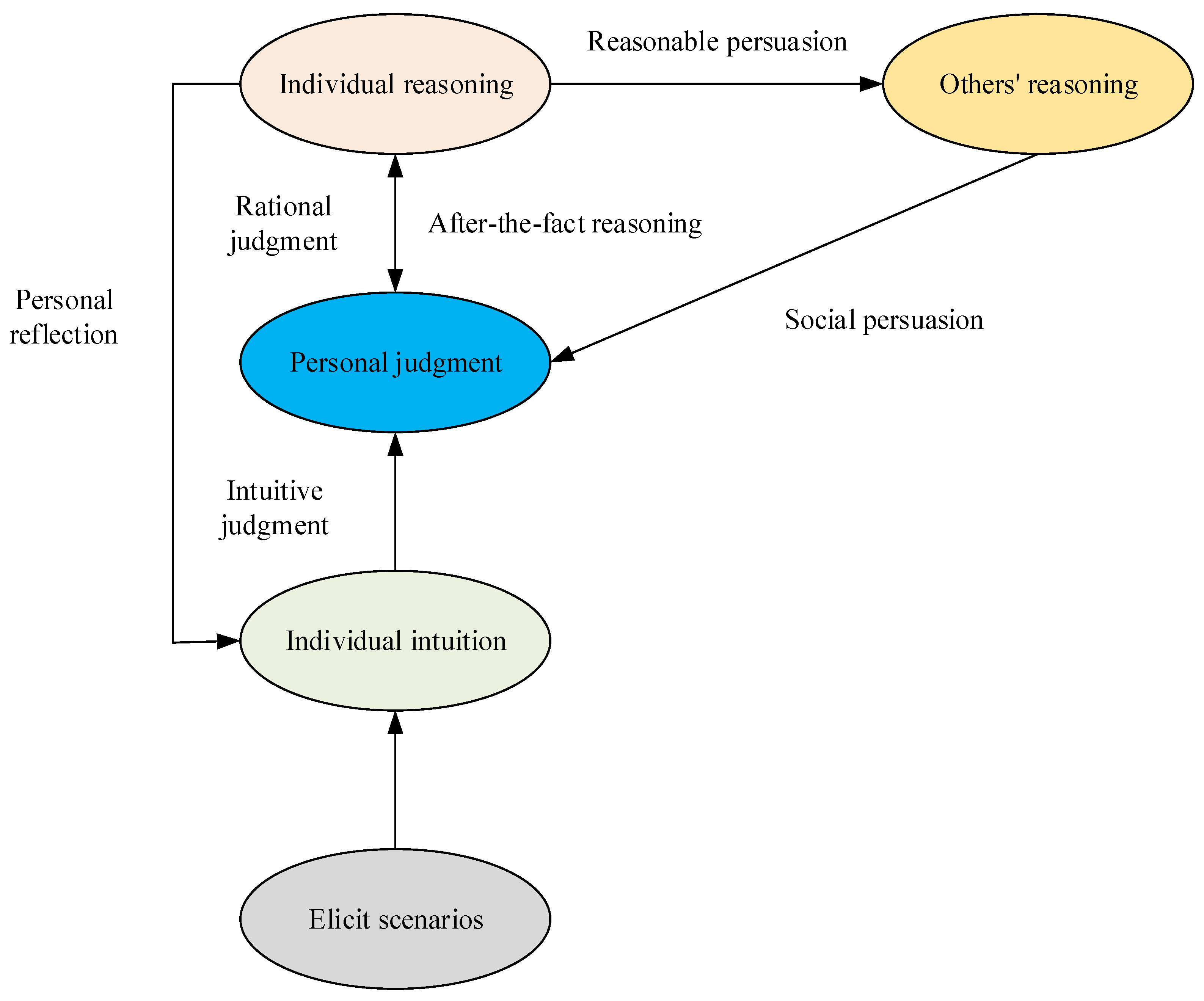

17]. Hadit believed that intuition directly leads individuals to make corresponding moral judgments. This is a cognition, not a reasoning process. Thus, the main idea of the theory is that moral judgments arise from quick moral intuitions, often accompanied by a slow process of reasoning, as shown in

Figure 1. Individual intuition leads to judgment. Discussing the reasons for judgment is to find reasons from the results to justify one’s decision. However, the ethical decision-making and personal reflection aspects of this process are almost nonexistent [

18].

Moral decision is the last link of moral choice, that is, the final decision made by the subject in the process of moral choice. That is to say, when the actor is faced with a variety of possible ways to choose, the final decision on the degree of good and evil and the morality of these possible behavioral ways is the final decision [

19], that is, the result of moral decision-making under the balance of pros and cons. The study of moral decision-making has always been accompanied by disputes of schools, mainly because the measurement of moral decision-making is usually associated with moral dilemma situations, and individuals are often in the contradiction between rational analysis and perceptual intuition. These two ways of thinking also correspond to different decision-making principles, namely, the principle of utilitarianism and the principle of altruism. Beverly, on the other hand, argued that moral decision-making can be either a responsive decision about how to behave in a real or hypothetical moral dilemma (when a choice of response is needed, accompanied by certain moral rules or principles), or a judgment about the moral acceptability of behavior or the moral qualities of others (including judgments about individuals, groups, or institutions) [

20]. Hadit believed that it is moral intuition that directly leads individuals to make corresponding moral judgments, which is a kind of cognition, not a reasoning process. Thus, the main point of the theory is that moral judgments are caused by quick moral intuitions, followed by a slow process of moral reasoning when necessary [

21]. After analyzing and integrating the research results of Hadt et al., Greene proposed a dual-processing theoretical model of moral decision-making from the perspective of cognitive neuroscience. Its theory discusses the decision-making tendency of consequentialism and deontology; the former is driven by cognitive process, while the latter is driven by emotion. In addition, he divided moral judgment into two categories, personal and nonpersonal, i.e., personal is driven by social emotional responses (e.g., in a footbridge dilemma, an individual is required to push another person through physical touch to save another person, and the individual is more directly affected by his or her own emotions), while nonpersonal is less driven by emotional responses and more determined by cognitive processes (e.g., in a trolley dilemma, an individual is required to pull the lever). In his research, “cognition” is not an information processing process, but is defined as a process that contrasts with emotion [

22]. In specific studies, Greene also used the dilemma to test the dual-processing theory, and came to the following conclusion that in the trolley dilemma, the cognitive process can compete with the emotional process, prompting people to recognize individual harmful moral violations; that is, in the case of low emotional response, people tend to be consequential. In a situation like the footbridge dilemma, individuals experience a large number of negative emotional reactions, causing individuals to disapprove of harmful behaviors; that is, in the case of high emotional reactions, people tend to make deontological decisions [

23]. Regarding the study of psychological distance, Trope and Liberman, through experimental support, introduced the concept of “psychological distance” in the field of psychology for the first time, and defined psychological distance as the range formed by individuals extending outward along four different dimensions: time, space, social relations, and hypothetical with their own time and position as reference points [

24]. Another widely used definition is from a social psychology perspective. Agnew focused on explaining the interpersonal distance dimension of psychological distance, that is, social distance. He believed that individuals are based on the collected social information and evaluate and judge the distance between themselves and external individuals after comprehensive analysis. However, the evaluation results are not always perceived by individuals, and may only occur subconsciously [

25]. Gong’s research confirms that when the set dilemma occurs when both spatial and temporal distances are far away, the individual ‘s decision-making results tend to be more utilitarian than when the psychological distance is close, and thus more choices are made to maximize benefits, even if the corresponding costs are greater [

26].

As for the study of moral decision-making of college students majoring in physical education, students in physical education colleges and universities, and college students majoring in physical education in other colleges and universities, because many of them have received physical training since childhood, the proportion of cultural knowledge and ideological education is much less than that of students in ordinary colleges and universities, and their personal values are mostly judged by the results obtained in the competition or by winning or losing. In the long run, this has led to the emphasis on utilitarianism by this group. In life, it is mostly self-centered and interests first, with too much emphasis on results in competition regardless of moral norms or other people’s feelings. Then, with such obvious differences in the values of the two groups, the researchers began to compare and analyze their performance in the moral dilemma. Escolar-Chua first measured the moral judgment performance of two groups of college students and found that basketball players had lower moral judgment scores than nonsports individuals in four life and sports dilemmas [

27]. For the higher utilitarian decision-making tendency of basketball players, Stanger explained it as a collective project where basketball players belong. Even if they violate the rules, the punishment they receive is not always personal, so the price paid is within an acceptable range, and they dare to choose the choice of low risk and high return [

28]. There are many studies on the exploration of time pressure, among which some scholars pay attention to the decision-makers’ decision-making bias under time pressure and distraction in the hypothetical car purchase problem. It is proved that if individuals want to make some judgments involving personal investment under time pressure or distraction, they will rely heavily on negative evidence in the event [

29]. Zakay’s understanding of time pressure is that when the time allocated is less than the time required for decision-making or is considered to be required for decision-making, it may cause time tension and may damage the best performance of the decision-making process. As a background variable, time pressure affects the nature of the decision-making process, especially the strategy of decision-makers [

30].

4. Experimental Design and Performance Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Materials (or Datasets Collection)

This experiment adopts a mixed design of 3 (study learning pressure: high, medium, no) × 2 (spatial distance: Beijing, France) × 2 (social distance: self, others). Learning pressure is a between-subject variable. Spatial and social distance are both within-subject variables. The dependent variable is the number of times subjects made moral decisions. In the early stage of the experiment, it is judged and verified whether the selected dimension is effective for the experiment.

4.2. Experimental Environment

Schedule an experiment. In the sports scenario, 12 moral materials are selected. The situational content and decision-making remain unchanged, and only social and spatial distances are added to the original title.

Original title: In an important football game, you are fighting for possession of the ball with a good opponent who has suffered a leg injury. You know you can get the ball by kicking the player’s injured leg without being punished by the referee.

Will you please do this?

A. Yes B. No

The title after the adaptation is: (please imagine the following events in Beijing or France) In an important football match, you (others) are fighting for possession of the ball with a good player who has a leg injury. You (the other person) know you can kick the player’s injured leg without being punished by the referee to gain possession.

Will you (or anyone else) do this?

A. Yes B. No

Manipulation of psychological distance mainly focuses on two dimensions, social and spatial distance. The initiation of psychological distance is generally reflected in the instruction language. Therefore, a preliminary test is conducted before the formal experiment to confirm that the distance of the psychological distance selected in the formal experiment can be effectively activated.

The questionnaire is conducted in the form of online distribution, and a total of 50 results are collected.

Psychological distance distinguishes between near and far. There are four questions below and no correct answer. Please start from your own actual situation, imagine, and perceive how far it is from you, and make the one that you think is closest to you. A seven-point scale is used to select a psychological distance.

Social distancing: 1. I am participating in competition; 2. He (she) is participating in a competition.

Spatial distance: 1. I participate in a game in Beijing; 2. I participate in a game in France.

Statistical results show that at least 90% of individuals perceive psychological distance as expected. Thus, the pre-test results proved that manipulating social and spatial distance is effective.

4.3. Parameters Setting

Before the start of the experiment, the subjects should be informed in advance that they will participate in a decision-making experiment in a movement dilemma situation. The steps are as follows:

- (1)

The stress group without learning

After the subjects are ready, the instruction language presented is as follows: welcome to participate in this experiment! In order to familiarize yourself with the experimental process, please understand the instructions before entering this experiment. After the “+” gaze point appears on the computer screen, please focus on the center of the computer screen. Next, the segment context description will appear. Immediately after each situation has been read, press the space bar to enter the question page and make a “yes” or “no” choice. If you think the answer is “yes,” press the “Y” key on your keyboard. If you think the answer is “no”, press the “N” key. The descriptions are hypothetical situations, and please imagine as much as possible based on the information in the question statement. There is no absolute right or wrong answer to the question. I hope you can choose according to your own ideas! After understanding the above instructions, please press the “Q” key to enter the formal experiment [

32].

- (2)

(Medium/High) Study Pressure Group

After the subjects are ready, the instruction language presented is as follows: welcome to participate in this experiment! In order to familiarize you with the experimental process, please understand the instructions before entering this experiment. After the “+” gaze point appears on the computer screen, please focus on the center of the computer screen. Then, a situation description will appear on the screen (normal college students need 8 s to read it completely, but in this experiment, the presentation time is only 4 s (or 6 s), so please pay attention. After that, the page will automatically jump to the answer page and ask you to make a “yes” or “no” choice. If you think the answer is “yes,” please press the “Y” key on your keyboard. If you think the answer is “no,” press the “N” key. The descriptions are all hypothetical situations. Please imagine as much as possible based on the information in the question statement. There is no absolute right or wrong answer to the question, and I hope you can choose according to your own ideas! After understanding the above instruction, now, please press the “Q” key to enter the formal experiment [

33].

4.4. Performance Evaluation

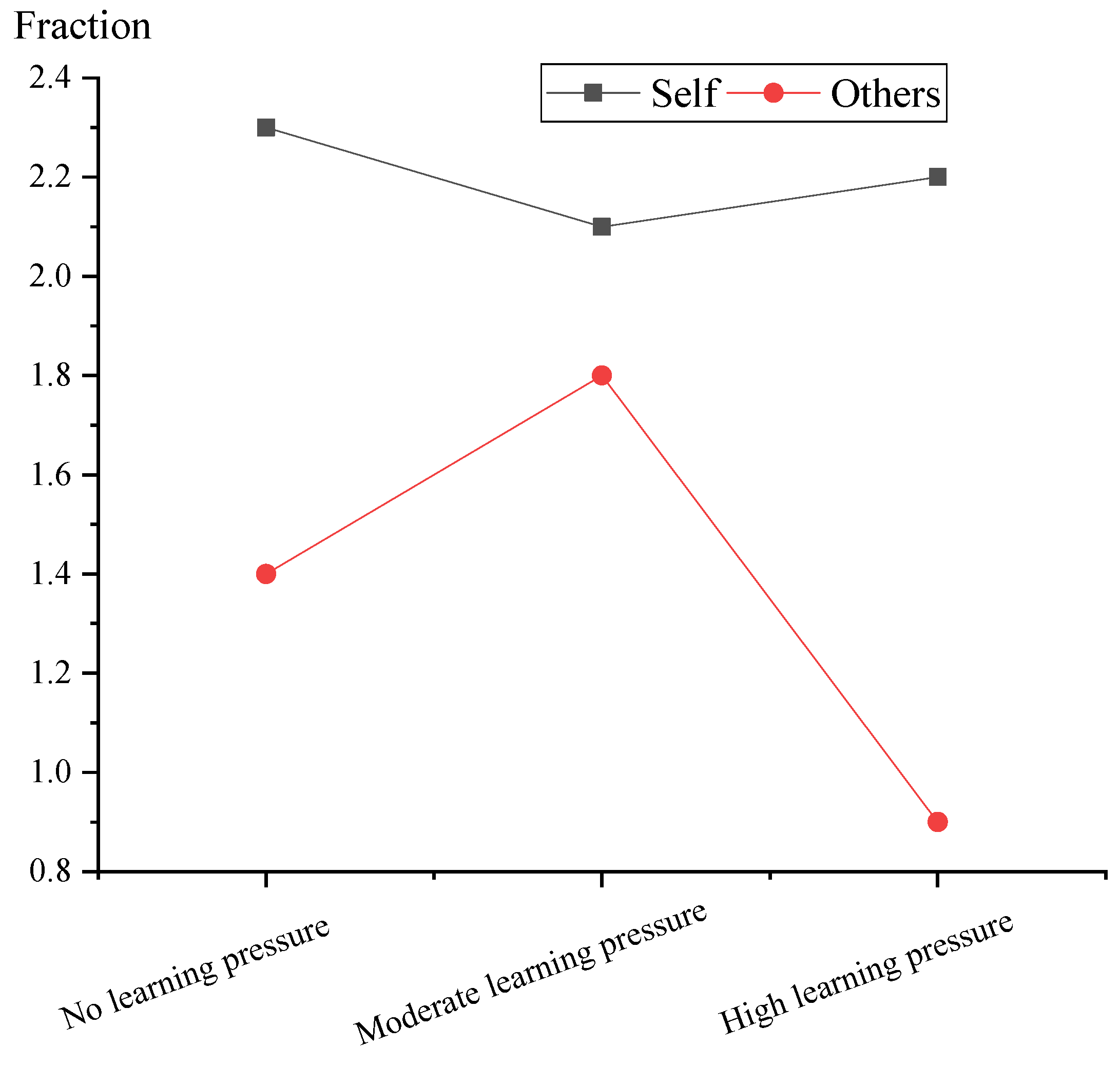

Learning pressure, social distance, and spatial distance are independent variables. The number of moral decisions made by the subjects is used as the dependent variable, and a three-way repeated-measures ANOVA is performed. Under each experimental condition, the results of the subjects making moral decisions are descriptive statistics, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 3 presents the variance analysis of learning pressure × social distance × spatial distance on utilitarian decision-making.

The main effect of social distance is very significant (F = 12.017,

p < 0.01), indicating a significant difference in the decision-making choices of the subjects when the decision-making body is themselves, and the decision-making body is others. The subjects made moral decisions with the self as the main body significantly higher than others. The main effect of learning pressure is not significant (F = 0.820,

p = 0.206), and the main effect of spatial distance is not significant (F = 0.884,

p = 0.355). The interaction between learning pressure and social distance is significantly different (F = 4.703,

p < 0.05). There is a significant difference in the interaction of learning pressure and spatial distance (F = 8.776,

p < 0.06). The interaction between social and spatial distance is not significant (F = 14.52,

p = 0.236). The interactions of learning pressure, social distance, and spatial distance are also not significant (F = 0.830,

p = 0.540). Study pressure and social distance are further analyzed by simple effects. The results show that there are significant differences in moral decision-making between the far and near dimensions of social distance, regardless of the condition of no learning (F = 11.128,

p < 0.05) or high learning pressure (F = 10.043,

p < 0.05). The utilitarian decisions made by individuals with the self as the decision-making subject are significantly higher than those made by others. Under moderate learning pressure, there is no significant difference in decision-making results between self and others (F = 0.850,

p = 0.412); that is, under moderate learning pressure, social distance does not affect individuals’ moral decision-making. The pressure value is 1–3 points, indicating that the pressure value is increasing. The pressure values under different conditions are shown in

Figure 2.

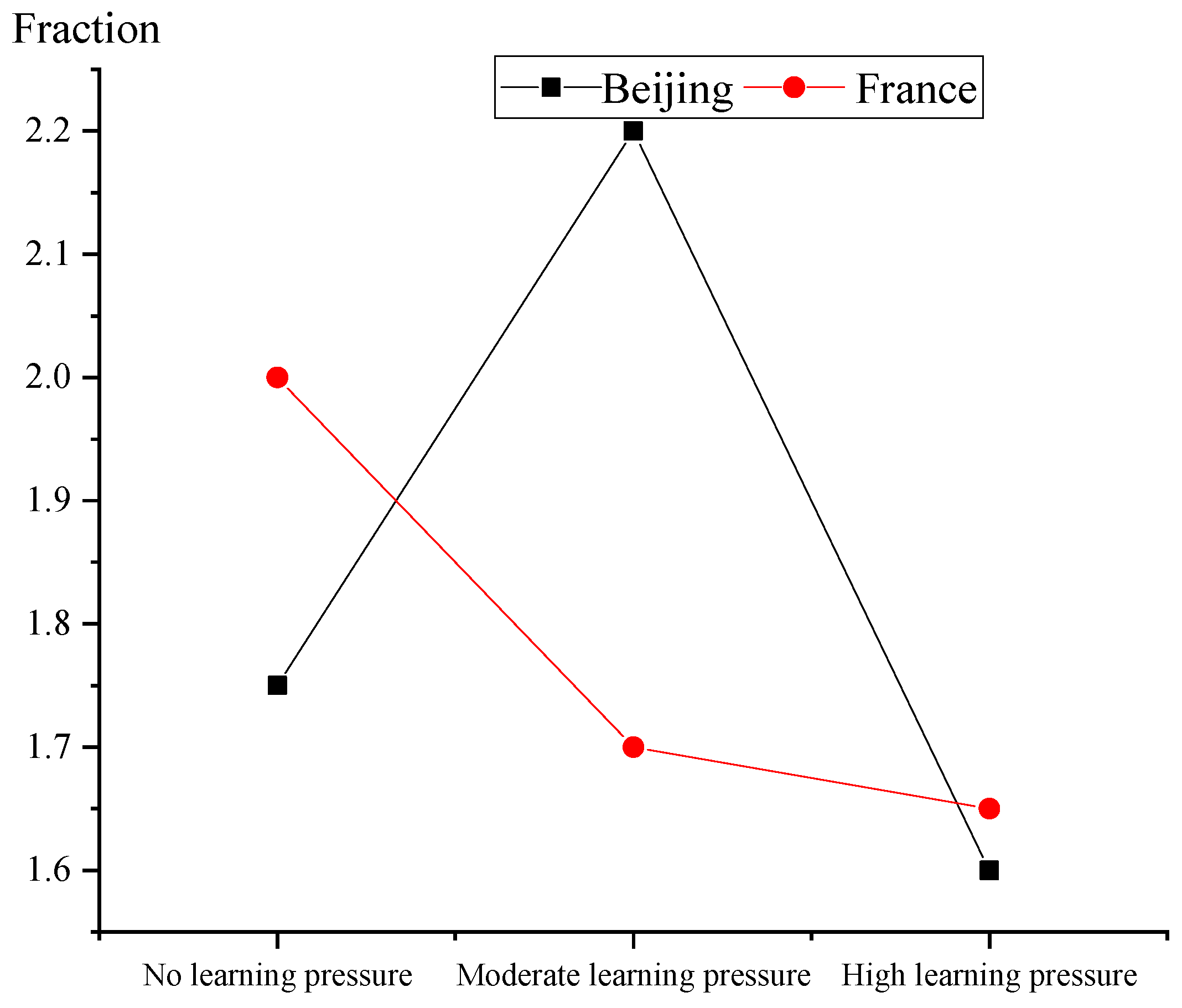

In

Figure 2, the further simple-effects analysis of learning pressure and spatial distance found that in the condition of moderate learning pressure (F = 4.475,

p < 0.05), there are significant differences in the moral decision-making of subjects in the far and near dimensions of spatial distance. The moral decisions made by individuals in Beijing as the background of the event are significantly higher than those in France. In the absence of learning pressure, there is no significant difference in decision-making results between Beijing and France (F = 3.813,

p = 0.058). Similarly, under high learning pressure, there is no significant difference in the decision-making results of the subjects in the two dimensions of spatial distance (F = 3.813,

p = 0.150). In the absence of learning pressure and high learning pressure, spatial distance does not affect individuals’ moral decision-making.

Figure 3 shows the interaction of learning pressure and spatial distance.

4.5. Discussion

This work explores the influence of two dimensions of psychological distance based on learning pressure: spatial distance and social distance, on moral decision-making. After the four levels of psychological distance and different levels of learning and pressure are combined, the change in an individual’s decision-making behavior in the motor dilemmas is analyzed [

34].

Experimental result 1 is that the main effect of social distance is significant. Individuals with closer social distance tend to make utilitarian decisions when making decisions. When social distancing is greater, individuals are more inclined to make deontological decisions.

Experimental result 2 is that spatial distance affects moral decision-making. When the background of the dilemma decision-making situation is Beijing, individuals tend to make utilitarian decisions. When the background of the dilemma decision-making situation is France, which is far away in space, individuals tend to make deontological decisions. Individuals tend to be harsher in their judgments about events at greater spatial distances, so it is easier to judge them as immoral. However, in the research on spatial distance and moral judgment and decision-making, individuals tend to adopt stricter standards for evaluating events or behaviors with close spatial distance, and it is easier to make deontological decisions.

Experimental result 3 is that the interaction between learning pressure and social distance is significant, and the simple effect of social distance is significant at a low level of learning pressure (i.e., when there is no pressure). The simple effect is significant at high levels of learning stress. However, the simple effect is not significant at the medium level of learning stress. When the subject of the event is the individual self, individuals tend to make moral decisions under both stress-free and high-stress conditions. When the decision subject is changed to someone the individual is unfamiliar with, the number of moral decisions is significantly reduced [

35].

Changes in social and spatial distance dimensions can alter individuals’ tendency to make moral decisions under different learning stress conditions. In the socially close dilemma, individuals with no and high learning pressure increase the number of moral decisions. In the spatially distant dilemma, individuals under moderate learning pressure increase the number of moral decisions. The data suggest that spatial and social distancing influences the propensity to make moral decisions. Previous studies have also confirmed that time pressure will speed up individual decision-making time. The experiment shows that the decision-making time of the fresh PE student group under high time pressure (1077.93/2302.98 ms) is faster than that under no time pressure (1994.83/2363.63 ms). The nonsports group also had less decision-making time in the sports dilemma than without time pressure. However, the decision-making time of the nongraduating sports student group increased slightly in the life dilemma under the condition of high time pressure. The reason may be that the scenes described in the life dilemma are closely related to personal job search and other people’s lives [

36]. Due to the existence of time pressure, individuals may not have enough information about the description of the predicament, but they cannot easily make the choice to decide their fate, so the thinking time may be a little longer. In addition, in the plight of life, sports college students have the least reaction time under high time pressure, indicating that when individuals face life difficulties, they need to consider the moral rules and need to weigh more information than in the sports situation, so the information processing process is shorter to make decisions faster. It takes the longest time for ordinary professional college students to make decisions without pressure, indicating that due to the lack of background knowledge of sports competitions, individuals are not very clear about the severity of each moral anomie behavior [

37]. They have to grasp all the information mentioned in the dilemma, and then weigh which choice has the highest return ratio between winning the game with fouls and obeying the rules but losing the game, so their thinking process is more complicated and takes longer decision-making time.

5. Conclusions

The results show that in the context of IoT and machine learning, there is no significant difference in the moral decision-making of college students in general majors and sports majors. The education received by the college students majoring in sports is more about the spirit of sports competition. Their achievement motivation is generally higher, and they are more familiar with sports rules. Based on this cognitive background, ordinary professional college students are more likely to make more harmful behaviors in the sports dilemma, that is, to choose result-oriented decisions. College students majoring in sports are less likely to exhibit some behaviors that violate the spirit of competition, such as passive competition and doping. Their decision-making is not just about the outcome but more about the ethical trade-offs involved in the event. Under high study pressure, both general and sports college students choose to make more utilitarian decisions, and the decision-making tendency in sports dilemmas is higher than that in life dilemmas. Under no learning pressure, both general and sports college students choose to make more deontological decisions. The decision-making tendency in sports dilemmas is higher than that in life dilemmas. This is consistent with the conclusions of previous studies. Without considering other factors, individuals are under high learning pressure and are more inclined to result-oriented utilitarian decision-making. The factor of learning pressure is added to produce a certain sense of urgency in the individual decision-making process. Whether it is a sports major or an ordinary professional college student, the cognitive processing process cannot be carried out completely, thus ignoring the disadvantages brought by breaking the rules. They only notice the egoistic nature of the results. Therefore, individuals under high learning stress are more egoistic in their choices than students under no stress.

5.1. Research Contribution

From a realistic point of view, the thinking and analysis of the current situation of moral education in contemporary colleges and universities systematically analyze the guiding ability of moral education in colleges and universities under the new media environment. The effectiveness and pertinence of moral education are improved. Thus, this work is also very meaningful in practical work. The new media has a wide range of readers in colleges and universities, and it profoundly impacts the moral education of colleges and universities. Therefore, this work analyzes and excavates the value of theory and practice and moral education in colleges and universities.

The experimental results support hypothesis one and hypothesis two, and partially support hypothesis three. Graduated sports college students have a stronger tendency. Graduated PE students and fresh PE students have similar ways of thinking about moral cognition, so when facing the dilemma of life, everyone will choose the result of altruism. However, due to the sports dilemma, the education received by college students majoring in physical education is more about the spirit of sports competition, their achievement motivation is generally higher, and they are more familiar with the rules of sports. Therefore, based on this cognitive background, there are fresh college students majoring in physical education who are more likely to make more harmful behaviors in the sports dilemma, that is, to choose result-oriented decision-making. When they make decisions, they not only consider the results, but also weigh the ethics involved in the event. The experimental results show that under no time and high time pressure, when the self is the decision-making subject, utilitarian decision-making is preferred; especially under no time pressure, the utilitarian choice is highest, but when the decision-making subject is others, individuals are more likely to make deontological decisions. This may be because the situation we face is related to ourselves, with a higher situation involved; thus, considering the problem may be taken with more care, may be more comprehensive, and may be more susceptible to the results, so individuals tend to make utilitarian choices. However, when the spatial distance is closer, the higher the time pressure an individual perceives, the easier it is to make deontological decisions. Simply, the less important information an individual pays attention to and the less complete the cognitive process, the more the individual tends to be conservative rather than risk foul. However, if the decision-making scene occurs at a long distance, even if the information is insufficient, the individual will choose to make a risky decision, which may be because the individual is more tolerant of injury and violations in the long-distance sports scene.

5.2. Future Works and Research Limitations

- (1)

Disadvantages

The research on psychological distance only uses two dimensions, social and spatial distance. The actual psychological distance also includes two aspects, temporal distance and hypothetical, and the scope is not comprehensive enough.

The selected subjects are college students majoring in sports, and their representation is not particularly strong. Such students have less competition experience and are less aware of sportsmanship than professional athletes.

The timeliness of the control of learning pressure is not particularly strong. A learning pressure questionnaire should be added to test whether the subjects’ learning pressure manipulation during the experiment is effective.

- (2)

Future research directions

The four dimensions of psychological distance will be deeply explored for moral decision-making, especially the influence of sports on moral decision-making.

More representative subjects will be selected. Additionally, the analysis of the content of the network environment will be strengthened. Study pressure and whether to apply IoT technology will be researched. The exploration of sports ethics’ anomie behavior is more appropriate and pertinent.

The sports dilemma of sports majors in different types will be discussed more deeply. The tolerance of sports college students and even athletes to moral misconduct will be analyzed and improved.