Temperament, Character and Cognitive Emotional Regulation in the Latent Profile Classification of Smartphone Addiction in University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ① Is there a latent profile group classification for smartphone addiction?

- ② Is there a difference between groups according to smartphone addiction latent profile classification?

- ③ Are there differences according to temperament and character and cognitive and emotional control strategies in the group according to smartphone addiction latent profile classification?

- ④ Are there any differences in the effect relationships between groups according to smartphone addiction latent profile classification?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Smartphone Addiction Scale Based on Behavioral Addiction Criteria (SAS-B)

2.2.2. Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI)

2.2.3. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Latent Profiles of Smartphone Addiction

3.2. Validation of Group Differences according to Smartphone Addiction Latent Profiles

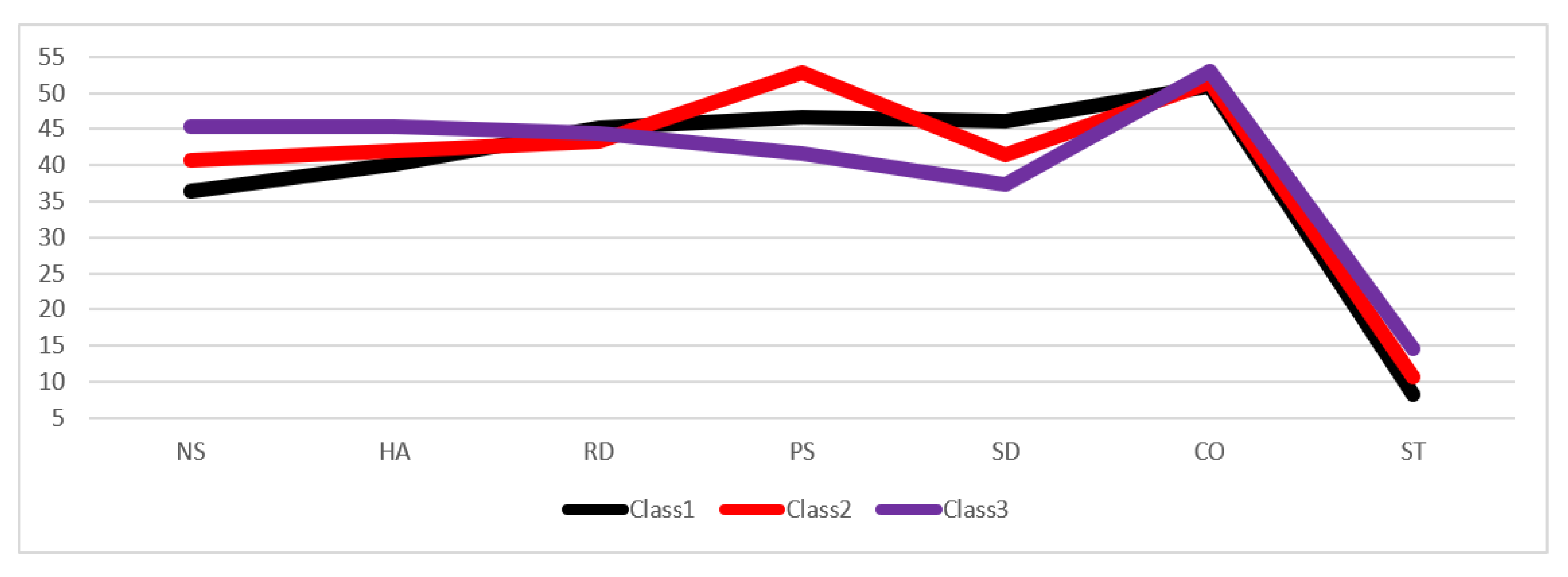

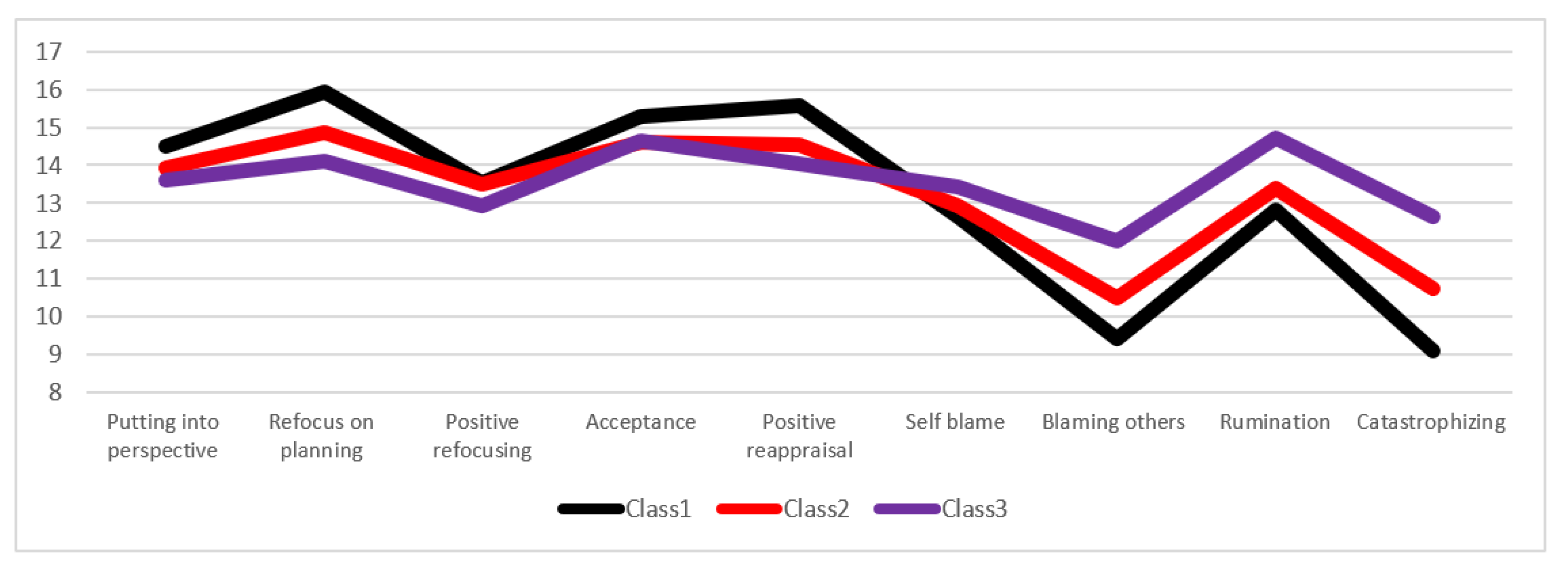

3.3. Group Differences in Temperament and Character, Cognitive and Emotional Control Strategy

3.4. Validation of Influence Relationships according to Smartphone Addiction Latent Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonçalves, S.; Dias, P.; Correia, A.P. Nomophobia and lifestyle: Smartphone use and its relationship to psychopathologies. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2020, 2, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J. Analysis of Problemic Smartphone Use and Life Satisfaction by Smartphone Usage Type. J. Korea Game Soc. 2020, 20, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özaslan, A.; Yıldırım, M.; Guney, E.; Guzel, H.S.; Iseri, E. Association between problematic internet use, quality of parent-adolescents relationship, conflicts, and mental health problems. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 2503–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.A.; Sandra, D.A.; Colucci, É.S.; Bikaii, A.A.; Nahas, J.; Chmoule-vitch, D.; Veissière, S.P.L. Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.W. Physical activity level, sleep quality, attention control and self-regulated learning along to smartphone addiction among college students. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. (JKAIS) 2015, 16, 429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.S.; Lee, H.K.; Ha, J.C. The influence of smartphone addiction on mental health, campus life and personal relations-Focusing on K university students. J. Korean Data Inf. Sci. Soc. 2012, 23, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.X.; Wu, A.M. Effects of smartphone addiction on sleep quality among Chinese university students: The mediating role of self-regulation and bedtime procrastination. Addict. Behav. 2020, 111, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newzoo. Global Mobile Market Report, 2021. Available online: https://newzoo.com/insights/trend-reports/newzoo-global-mobile-market-report-2021-free-version/Google Scholar (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Statiosta(2022). How Many People Have Smartphones Worldwide (Jan 2022). Available online: https://bankmycell.com (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Sebire, K. The Coronavirus Lockdown is Forcing Us to View ‘Screen Time’ Differently. That’s a Good Thing. 2020. Available online: https://theconversation.com/the-coronavirus-lockdown-is-forcing-us-to-view-screen-time-differently-thats-a-good-thing-135641 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Chen, I.-H.; Pakpour, A.H.; Leung, H.; Potenza, M.N.; Su, J.A.; Lin, C.-Y.; Griffiths, M.D. Comparing generalized and specific problematic smartphone/internet use: Longitudinal relationships between smartphone application-based addiction and social media addiction and psychological distress. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, S.; Castro, R.P.; Kwon, M.; Filler, A.; Kowatsch, T.; Schaub, M.P. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Internet addiction: Fact or fiction? Psychologist 1999, 12, 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther, A.D.; Heeren, A.; Schimmenti, A.; Van Rooij, P.; Maurage, M.; Carras, M.; Edman, J.; Blaszczynski, A.; Khazaal, Y.; Billieux, J. How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction. 2017, 112, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panova, T.; Carbonell, X. Is smartphone addiction really an addiction? J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satchell, L.P.; Fido, D.; Harper, C.A.; Shaw, H.; Davidson, B.; Ellis, D.A.; Hart, C.M.; Jalil, R.; Bartoli, A.J.; Kaye, L.K. Development of an Offline-Friend Addiction Questionnaire (O-FAQ): Are most people really social addicts? Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billieux, J. Problematic use of the mobile phone: A literature review and a pathways model. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2012, 8, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Sussman, S. Does smartphone addiction fall on a continuum of addictive behaviors? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L. Big five personality and adolescent Internet addiction: The mediating role of coping style. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. The myth of ‘addictive personality’. Glob. J. Addict. Rehabil. Med. (GJARM) 2017, 3, 555610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Chang, C.T.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, Z.H. The dark side of smartphone usage: Psychological traits, compulsive behavior and technostress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Jain, N.K. Compulsive smartphone usage and users’ ill-being among young Indians: Does personality matter? Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Jeong, Y.; Suh, B.; Gweon, G. Is smartphone addiction different from Internet addiction? comparison of addiction-risk factors among adolescents. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M.D. Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błachnio, A.; Przepiorka, A.; Senol-Durak, E.; Durak, M.; Sherstyuk, L. The role of personality traits in Facebook and Internet addictions: A study on Polish, Turkish, and Ukrainian samples. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R. Exploring the effects of demographic factors, Internet usage and personality traits on Internet addiction in a sample of Italian university students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.R.; Oh, H.S.; Jo, M.H. The Relationship among Temperament, Ambivalence over Emotional Expressiveness, Stress Coping Style, and Smartphone Addiction. Korean Journal of Health Psychology. Korean J. Psychol. Health 2018, 23, 271–292. [Google Scholar]

- Takao, M. Problematic mobile phone use and big-five personality domains. Indian J. Community Med. Off. Publ. Indian Assoc. Prev. Soc. Med. 2014, 39, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, S.R. Personality Theories: A Comparative Analysis, 5th ed.; Dorsey: Homewood, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Digman, J.M. Personality structure: Emergence of the five- factor model. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1989, 41, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, S.; Phillips, J.G. Personality and self reported mobile phone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, W.; Manner, C. The impact of personality traits on smartphone ownership and use. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Chris-Manner-2/publication/265480996_The_Impact_of_Personality_Traits_on_Smartphone_Ownership_and_Use/links/586f8caa08ae329d6215ff48/The-Impact-of-Personality-Traits-on-Smartphone-Ownership-and-Use.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Hussain, Z.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sheffield, D. An investigation into problematic smartphone use: The role of narcissism, anxiety, and personality factors. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacis, L.; Griffiths, M.D.; Limone, P.; Sinatra, M.; Servidio, R. Selfitis behavior: Assessing the Italian version of the Selfitis Behavior Scale and its mediating role in the relationship of dark traits with social media addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Ahadi, S.A.; Evans, D.E. Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.F.; Gorsuch, R.L. Forgiveness within the Big Five personality model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, H.J. The Dynamics of Anxiety and Hysteria: An Experimental Application of Modern Learning Theory to Psychiatry; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Stallings, M.C.; Hewitt, J.K.; Cloninger, C.R.; Heath, A.C.; Eaves, L.J. Genetic and environmental structure of the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire: Three or four temperament dimensions? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Svrakic, D.M.; Przybeck, T.R. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1993, 50, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.S. Problems of temperament and attention deficits affecting autonomy-mediated juvenile delinquency. Educ. Cult. Res. 2018, 24, 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, M.; Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Nie, J.; Lei, L. Can emotion regulation difficulty lead to adolescent problematic smartphone use? A moderated mediation model of depression and perceived social support. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 108, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanjani, Z.; Moghbeli Hanzaii, M.; Mohsenabadi, H. The relationship of depression, distress tolerance and difficulty in emotional regulation with addiction to cell-phone use in students of Kashan University. Feyz J. Kashan Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 22, 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, P.J. Reinforcement sensitivity theory (RST): Introduction. In The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle, W. Personality processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1995, 46, 295–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y. The relationship between mother’s psychological control and smartphone addiction tendency perceived by elementary school students: Mediating effect of cognitive emotion regulation strategy. East-West Psychiatry 2020, 23, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y. The effect of smartphone addiction in adults on subjective well-being: The double-mediated effect of executive function deficits and adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Digit. Converg. Res. 2019, 17, 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.Y. The mediating effect of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategy and negative emotions on the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction. J. Korean Contents Assoc. 2018, 18, 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Senior, S. The effect of parental attachment on smartphone addiction: The mediating effect of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation. Youth Stud. 2017, 24, 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, D.; Atkins, R.; Fegley, S.; Robins, R.W.; Tracy, J.L. Personality and development in childhood: A person-centered approach. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2003, 68, 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abendroth, A.; Parry, D.A.; Roux, D.B.L.; Gundlach, J. An analysis of problematic media use and technology use addiction scales–what are they actually assessing? In Conference on E-Business, E-Services and e-Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, B.I.; Shaw, H.; Ellis, D. Fuzzy Constructs: The Overlap between Mental Health and Technology ‘Use’; School of Management, University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Lim, J.M.; Son, H.B.; Kwak, H.W.; Chang, M.S. Development and Validation of a Smartphone Addiction Scale Based on Behavioral Addiction Criteria. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2016, 28, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmal, N. The role of temperament in human behavior. Web Sci. Int. Sci. Res. J. 2021, 2, 60–74. [Google Scholar]

- Min, B.B.; Oh, H.S.; Lee, S.Y. Temperament and Character Inventroy Menual. Soul Maumsarang. 2007, 6, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 30, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. Study on Relationships Among the Stressful Events, Cognitive Emotion ReguIation Strategies and Psycholocal Well-Being. J. Stud. Guid. Couns. 2008, 26, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Helsen, K.; Jedidi, K.; DeSarbo, W.S. A new approach to country segmentation utilizing multinational diffusion patterns. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.H.; Kang, E.N. A Study of Social Network Type among Korean Older Persons: Focusing on Network Size, Frequencies of Contact, and Closeness. J. Korea Gerontol. Soc. 2016, 36, 765–783. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Y.; Mendell, N.R.; Rubin, D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.; Hussain, Z. Smartphone addiction and associated psychological factors. Addicta Turk. J. Addict. 2016, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Tiamiyu, M.F.; Weeks, J.W.; Levine, J.C.; Picard, K.J.; Hall, B.J. Depression and emotion regulation predict objective smartphone use measured over one week. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 133, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N.; Quintana-Orts, C.; Sánchez-Álvarez, N.; Rey, L. The role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies on problematic smartphone use: Comparison between problematic and non-problematic adolescent users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Yildirim, C.; Alghraibeh, A.M.; Alafnan, A.A. Worry and anger are associated with latent classes of problematic smartphone use severity among college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, M.; Li, C.; Bao, H. The relationships between negative emotions and latent classes of smartphone addiction. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeum, D.M. Latent Profile Analysis on Smart Phone Dependence of Elementary School Students. J. Rehabil. Welf. Eng. Assist. Technol. (J. RWEAT) 2017, 11, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.C.; Deng, Q.; Bi, X.; Ye, H.; Yang, W. Performance of the entropy as an index of classification accuracy in latent profile analysis: A monte carlo simulation study. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2017, 49, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.B.; Wu, A.M.; Feng, L.F.; Deng, Y.; Li, J.H.; Chen, Y.X.; Lau, J.T. Classification of probable online social networking addiction: A latent profile analysis from a large-scale survey among Chinese adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylund-Gibson, K.; Choi, A.Y. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2018, 4, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, É.; Montag, C. Smartphone addiction and beyond: Initial insights on an emerging research topic and its relationship to Internet addiction. In Internet Addiction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann, B.; Duke, É.; Sariyska, R.; Montag, C. Who’s addicted to the smartphone and/or the Internet? Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2019, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohta, R.; Halder, S. A comparative study on cognitive, emotional, and social functioning in adolescents with and without smartphone addiction. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2021, 17, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsido, A.N.; Arato, N.; Lang, A.; Labadi, B.; Stecina, D.; Bandi, S.A. The role of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and social anxiety in problematic smartphone and social media use. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 173, 110647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.S.; Choi, Y.H. The effectiveness of a Autonomous Regulation Improvement Smoking Cessation Program on the Amount of Daily Smoking, Perceived Motivation, Cotinine in Saliva, and Autonomous Regulation for Girls High School Students who Smoked. J. Korea Acad. -Ind. Coop. Soc. (JKAIS) 2015, 16, 6169–6179. [Google Scholar]

- Adinda, D.; Marquet, P. Effects of Blended Learning Teaching Strategies on Students’ Self-Direction. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on e-Learning, Cape Town, South Africa, 5–6 July 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg, W.A.; Igou, E.R. Boredom begs to differ: Differentiation from other negative emotions. Emotion 2017, 17, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bench, S.W.; Lench, H.C. Boredom as a seeking state: Boredom prompts the pursuit of novel (even negative) experiences. Emotion 2019, 19, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Vasquez, J.K.; Lustgarten, S.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Proneness to boredom mediates relationships between problematic smartphone use with depression and anxiety severity. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2018, 36, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Liu, Q.Q.; Lian, S.L.; Zhou, Z.K. Are bored minds more likely to be addicted? The relationship between boredom proneness and problematic mobile phone use. Addict. Behav. 2020, 108, 106426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, M.; Aderka, I.M. Gender differences in social anxiety disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterka-Bonetta, J.; Sindermann, C.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. Personality associations with smartphone and internet use disorder: A comparison study including links to impulsivity and social anxiety. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, P.E. Cognitive and behavioural approaches to changing addictive behaviours. In Addictive Behaviour; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1996; pp. 158–175. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Xiao, T.; Yang, L.; Loprinzi, P.D. Exercise as an alternative approach for treating smartphone addiction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of random controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinauskas, R.; Malinauskiene, V. A meta-analysis of psychological interventions for Internet/smartphone addiction among adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, B.; Hoff, E. Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2006, 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male age (N = 180) | 22.5 (2.3) | |

| Female age (N = 153) | 21.95 (2.738) | ||

| Smartphone addiction | Salience | 9.07 (3.417) | |

| Mood modification | 11.52 (3.707) | ||

| Tolerance | 11.68 (3.324) | ||

| Withdrawal | 10.33 (3.012) | ||

| Conflict | 9.42 (3.738) | ||

| Relapse | 9.72 (3.870) | ||

| Personality | Temperament | Novelty-seeking NS | 39.66 (9.804) |

| Harm Avoidance HA | 42.02 (10.360) | ||

| Reward Dependence RD | 44.25 (8.331) | ||

| Persistence PS | 44.18 (10.428) | ||

| Character | Self-Directedness SD | 42.6 (10.428) | |

| Cooperativeness CO | 51.37 (11.574) | ||

| Self-Transcendence ST | 30.88 (11.595) | ||

| Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategy | Adaptive Cognitive and Emotional Control Strategy | Putting into perspective | 14.10 (3.219) |

| Refocus on planning | 15.22 (32.146) | ||

| Positive refocusing | 13.44 (3.817) | ||

| Acceptance | 14.88 (2.683) | ||

| Positive reappraisal | 14.86 (3.458) | ||

| Maladaptive Cognitive and Emotional Control Strategy | Self-blame | 12.90 (3.260) | |

| Blaming others | 10.24 (3.924) | ||

| Rumination | 13.35 (3.021) | ||

| Catastrophizing | 10.35 (3.679) | ||

| Classification Criteria | Number of Latent Profiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Classification Qulity | Entropy | 0.848 | 0.848 | 0.805 | 0.831 | 0.850 |

| Information Reference Index | AIC | 9797.236 | 9657.831 | 9611.137 | 9578.483 | 9554.185 |

| BIC | 9869.590 | 9745.843 | 9726.805 | 9730.809 | 9773.167 | |

| SABIC | 9809.321 | 9674.369 | 9632.127 | 9604.926 | 9564.08 | |

| Model Comparison Validation | VLMRp | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.0138 * | 0.4771 | 0.1924 |

| LMRp | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.0154 * | 0.4886 | 0.1981 | |

| BLRTp | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | |

| N (%) | Class1 | 167 (0.49) | 135 (0.4) | 57 (0.18) | 62 (0.19) | 55 (0.16) |

| Class2 | 170 (0.51) | 159 (0.48) | 135 (0.4) | 21 (0.06) | 102 (0.31) | |

| Class3 | 39 (0.12) | 109 (0.32) | 92 (0.28) | 12 (0.04) | ||

| Class4 | 32 (0.1) | 127 (0.38) | 15 (0.05) | |||

| Class5 | 31 (0.09) | 31 (0.09) | ||||

| Class6 | 118 (0.35) | |||||

| Class1 (N = 135) | Class2 (N = 159) | Class3 (N = 39) | F | Scheffé | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Salience | 9.156 (0.349) | 12.527 (0.263) | 15.126 (0.604) | 150.495 *** | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Mood modification | 6.139 (0.254) | 10.586 (0.323) | 14.441 (0.393) | 78.529 *** | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Tolerance | 6.762 (0.261) | 10.535 (0.299) | 14.527 (0.402) | 301.316 *** | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Withdrawal | 9.362 (0.202) | 12.614 (0.207) | 14.925 (0.354) | 230.849 *** | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Conflict | 8.32 (0.257) | 10.784 (0.221) | 14.458 (0.439) | 259.727 *** | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Relapse | 14.509 (0.296) | 13.926 (0.283) | 13.601 (0.464) | 143.004 *** | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Class1 | Class2 | Class3 | F | Scheffé | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| Temperament | Novelty-Seeking NS | 36.35 (10.025) | 40.74 (8.058) | 45.41 (11.407) | 15.979 *** | 2, 3 > 1 |

| Harm Avoidance HA | 40.09 (11.857) | 41.96 (8.646) | 45.41 (7.622) | 4.496 * | 3 > 1, 2 | |

| Reward Dependence RD | 45.21 (8.474) | 43.36 (8.095) | 44.44 (8.494) | 1.813 | ||

| Persistence PS | 46.64 (11.567) | 52.89 (8.902) | 41.69 (10.509) | 6.308 ** | 1 > 2, 3 | |

| Character | Self-Directedness SD | 46.16 (11.172) | 41.44 (8.385) | 37.23 (7.436) | 16.66 *** | 1 > 2 > 3 |

| Cooperativeness CO | 50.94 (14.025) | 51.53 (9.82) | 53.03 (7.72) | 0.499 | ||

| Self-Transcendence ST | 8.32 (2.43) | 10.61 (1.966) | 14.64 (1.646) | 9.423 *** | 2, 3 > 1 | |

| Adaptive Cognitive and Emotional Control Strategy | Putting into perspective | 14.5 (3.138) | 13.92 (3.286) | 13.62 (2.917) | 1.787 | |

| Refocus on planning | 15.92 (3.093) | 14.87 (3.05) | 14.1(3.05) | 7.095 ** | 1 > 2, 3 | |

| Positive refocusing | 13.53 (3.501) | 13.51 (3.883) | 12.92 (3.601) | 0.426 | ||

| Acceptance | 15.28 (2.553) | 14.61 (2.797) | 14.64 (2.182) | 2.562 | ||

| Positive reappraisal | 15.56 (3.204) | 14.52 (3.563) | 14.05 (3.103) | 4.822 ** | 1 > 2, 3 | |

| Maladaptive Cognitive and Emotional Control Strategy | Self-blame | 12.63 (3.202) | 12.94 (3.347) | 13.44 (2.77) | 1.015 | |

| Blaming others | 9.41 (4.095) | 10.5 (3.561) | 12 (3.742) | 7.758 ** | 2, 3 > 1 | |

| Rumination | 12.8 (3.243) | 13.39 (2.815) | 14.72 (2.449) | 6.478 ** | 3 > 1, 2 | |

| Catastrophizing | 9.09 (3.707) | 10.73 (3.308) | 12.64 (3.674) | 17.822 *** | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Putting into perspective | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Refocus on planning | 0.513 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Positive refocusing | 0.421 ** | 0.4 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Acceptance | 0.520 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.429 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5. Positive reappraisal | 0.648 ** | 0.721 ** | 0.513 ** | 0.556 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 6. Self-blame | 0.356 ** | 0.363 ** | 0.171 * | 0.377 ** | 0.329 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 7. Blaming others | −0.256 ** | −0.373 ** | −0.057 | −0.284 ** | −0.368 ** | −0.191 * | 1 | ||||||||||

| 8.Rumination | 0.050 | 0.238 ** | 0.345 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.124 | 0.31 ** | 0.019 | 1 | |||||||||

| 9.Catastrophizing | −0.264 ** | −0.275 ** | 0.056 | −0.163 | −0.32 ** | 0.032 | 0.547 ** | 0.328 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 10.Novelty-Seeking NS | 0.062 | −0.034 | 0.108 | 0.074 | −0.080 | 0.121 | 0.271 ** | 0.065 | 0.201 * | 1 | |||||||

| 11.Novelty-Seeking NS | −0.025 | 0.082 | 0.047 | 0.032 | −0.052 | −0.114 | −0.089 | 0.253 ** | 0.063 | −0.027 | 1 | ||||||

| 12.Reward Dependence RD | 0.143 | 0.006 | 0.184 * | 0.173 * | 0.228 ** | 0.033 | 0.075 | 0.094 | 0.004 | 0.132 | −0.327 ** | 1 | |||||

| 13.Persistence PS | 0.103 | 0.193 * | 0.233 ** | 0.066 | 0.244 ** | −0.016 | 0.053 | −0.043 | 0.023 | −0.047 | −0.465 ** | 0.357 ** | 1 | ||||

| 14.Self-Directedness SD | 0.063 | 0.109 | 0.011 | 0.082 | 0.195 * | 0.004 | −0.115 | −0.181 * | −0.145 | −0.255 ** | −0.752 ** | 0.308 ** | 0.578 ** | 1 | |||

| 15.Cooperativeness CO | −0.019 | −0.048 | 0.154 | 0.038 | 0.073 | −0.017 | −0.047 | 0.050 | 0.015 | −0.231 ** | −0.452 ** | −0.506 ** | 0.547 ** | 0.564 ** | 1 | ||

| 16.Self-Transcendence ST | 0.305 ** | 0.223 ** | 0.312 ** | 0.3550 ** | 0.194 * | 0.182 * | 0.047 | 0.333 ** | 0.099 | 0.184 * | 0.265 ** | 0.056 | −0.083 | −0.239 ** | −0.219 * | 1 | |

| 17.Total score for smartphone addiction | 0.024 | −0.116 | 0.062 | 0.126 | −0.08 | −0.004 | 0.043 | 0.140 | 0.101 | 0.088 | 0.083 | 0.109 | −0.169 | −0.191 * | −0.038 | 0.166 | 1 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Putting into perspective | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Refocus on planning | 0.594 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Positive refocusing | 0.575 ** | 0.497 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Acceptance | 0.753 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.582 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5. Positive reappraisal | 0.666 ** | 0.714 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.72 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 6. Self-blame | 0.466 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.563 ** | 0.36 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 7. Blaming others | −0.23 ** | −0.2 * | −0.035 | −0.263 ** | −.244 ** | −0.151 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 8.Rumination | 0.289 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.329 ** | 0.416 ** | 0.171 * | 1 | |||||||||

| 9.Catastrophizing | −0.218 ** | −0.172 * | −0.008 | −0.159 * | −0.17 * | 0.003 | 0.696 ** | 0.696 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 10.Novelty-Seeking NS | 0.193 * | 0.171 * | 0.224 ** | 0.136 | 0.224 ** | 0.060 | 0.193 * | 0.201 * | 0.123 | 1 | |||||||

| 11.Novelty-Seeking NS | 0.022 | −0.146 | −0.063 | 0.055 | −0.062 | 0.135 | −0.016 | 0.065 | 0.060 | −0.036 | 1 | ||||||

| 12.Reward Dependence RD | −0.030 | 0.109 | −0.103 | −0.048 | −0.035 | −0.152 | 0.17 * | 0.120 | 0.101 | 0.141 | −0.293 ** | 1 | |||||

| 13.Persistence PS | −0.080 | 0.167 * | 0.155 | −0.053 | 0.132 | −0.130 | 0.325 ** | 0.2 * | 0.27 ** | 0.169 * | −0.299 ** | 0.2 3** | 1 | ||||

| 14.Self-Directedness SD | 0.037 | 0.198 * | 0.081 | 0.013 | 0.138 | −0.171 * | −0.018 | −0.012 | −0.101 | −0.199 * | −0.636 ** | 0.269 ** | 0.394 ** | 1 | |||

| 15.Cooperativeness CO | 0.055 | 0.173 * | 0.001 | 0.129 | 0.040 | 0.006 | 0.069 | 0.158 * | 0.078 | −0.040 | −0.216 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.468 ** | 0.388 ** | 1 | ||

| 16.Self-Transcendence ST | 0.16 * | 0.252 ** | 0.285 ** | 0.105 | 0.306 ** | 0.018 | 0.148 | 0.187 * | 0.219 ** | 0.378 ** | −0.044 | −0.117 | 0.22. ** | −0.064 | −0.213 ** | 1 | |

| 17.Total score for smartphone addiction | −0.120 | −0.222 ** | −0.018 | −0.103 | −0.175 * | 0.036 | 0.197 * | 0.015 | 0.255** | 0.185 * | 0.108 | −0.169 * | −0.021 | −0.113 | −0.044 | 0.127 | 1 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Putting into perspective | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Refocus on planning | 0.265 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Positive refocusing | 0.325 * | 0.310 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Acceptance | 0.528 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.251 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5. Positive reappraisal | 0.36 * | 0.528 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.391 * | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 6. Self-blame | 0.194 | 0.306 | 0.254 | 0.418 ** | 0.144 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 7. Blaming others | 0.039 | −0.083 | 0.283 | 0.023 | 0.233 | −0.135 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 8.Rumination | 0.003 | 0.339 * | 0.403 * | 0.448 ** | 0.047 | 0.403 * | −0.049 | 1 | |||||||||

| 9.Catastrophizing | −0.084 | −0.086 | 0.324 * | 0.131 | 0.094 | 0.468 ** | 0.415 ** | 0.377 * | 1 | ||||||||

| 10.Novelty-seeking NS | 0.088 | 0.135 | 0.384 * | 0.128 | 0.372 * | 0.286 | 0.494 ** | −0.119 | 0.48 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 11.Novelty-seeking NS | 0.064 | −0.226 | −0.085 | 0.090 | −0.35 * | 0.027 | 0.184 | 0.119 | 0.38 * | 0.085 | 1 | ||||||

| 12.Reward Dependence RD | 0.117 | 0.421 ** | 0.256 | 0.192 | 0.404 * | 0.300 | −0.017 | 0.257 | 0.240 | 0.256 | −0.049 | 1 | |||||

| 13.Persistence PS | 0.011 | 0.251 | 0.444 ** | 0.067 | 0.408 ** | 0.225 | 0.547 ** | −0.018 | 0.437 ** | 0.717 ** | −0.049 | 0.09 | 1 | ||||

| 14.Self-Directedness SD | −0.060 | 0.015 | −0.103 | −0.131 | 0.245 | −0.254 | −0.141 | −0.281 | −0.524 ** | −0.303 | −0.739 ** | −0.161 | −0.182 | 1 | |||

| 15.Cooperativeness CO | −0.129 | −0.090 | −0.007 | −0.017 | −0.009 | 0.045 | −0.207 | 0.209 | 0.172 | 0.030 | 0.066 | 0.32 * | −0.194 | −0.057 | 1 | ||

| 16.Self-Transcendence ST | 0.189 | 0.124 | 0.567 ** | 0.094 | 0.391 * | 0.198 | 0.476 ** | 0.26 | 0.584 ** | 0.569 ** | 0.236 | 0.187 | 0.61 ** | −0.373 * | −0.022 | 1 | |

| 17.Total score for smartphone addiction | 0.329 * | 0.261 | 0.248 | 0.424 ** | 0.312 | 0.155 | 0.492 ** | 0.328 * | 0.281 | 0.342 * | 0.247 | 0.322 * | 0.296 | −0.292 | −0.186 | 0.429 ** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | R | R 2 | F | Durbin-Watson Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score for smartphone addiction | Self-Directedness SD | −0.139 * | 0.191 | 0.029 | 5.058 * | 2.027 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | R | R 2 | F | Durbin-Watson Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score for smartphone addiction | Refocus on planning | −0.275 | 0.424 | 0.147 | 0.545 *** | 1.864 |

| Positive reappraisal | −0.225 | |||||

| Blaming others | −0.039 | |||||

| Catastrophizing | 0.458 * | |||||

| Novelty-seeking NS | 0.203 ** | |||||

| Reward Dependence RD | −0.18 ** |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | R | R 2 | F | Durbin-Watson Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score for smartphone addiction | Putting into perspective | 0.475 | 0.724 | 0.525 | 4.889 ** | 1.924 |

| Acceptance | 0.658 | |||||

| Blaming others | 0.96 * | |||||

| Rumination | 0.639 | |||||

| Novelty-Seeking NS | 0.008 | |||||

| Reward Dependence RD | 0.192 | |||||

| Self-Transcendence ST | 0.038 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, D.-H.; Jung, Y.-S. Temperament, Character and Cognitive Emotional Regulation in the Latent Profile Classification of Smartphone Addiction in University Students. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811643

Choi D-H, Jung Y-S. Temperament, Character and Cognitive Emotional Regulation in the Latent Profile Classification of Smartphone Addiction in University Students. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811643

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Dong-Hyun, and Young-Su Jung. 2022. "Temperament, Character and Cognitive Emotional Regulation in the Latent Profile Classification of Smartphone Addiction in University Students" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811643

APA StyleChoi, D.-H., & Jung, Y.-S. (2022). Temperament, Character and Cognitive Emotional Regulation in the Latent Profile Classification of Smartphone Addiction in University Students. Sustainability, 14(18), 11643. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811643