How the Experience Designs of Sustainable Festive Events Affect Cultural Emotion, Travel Motivation, and Behavioral Intention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Experience Designs of Festive Events

2.2. Cultural Emotion towards Festivals

2.3. Travel Motivation and Behavioral Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Framework and Hypotheses

3.2. Case Study

3.3. Research Tool

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.1.1. Convergent and Discrimination Validity

4.1.2. Multivariate Normality Tests

4.2. Structural Model Analysis and Hypotheses Verification

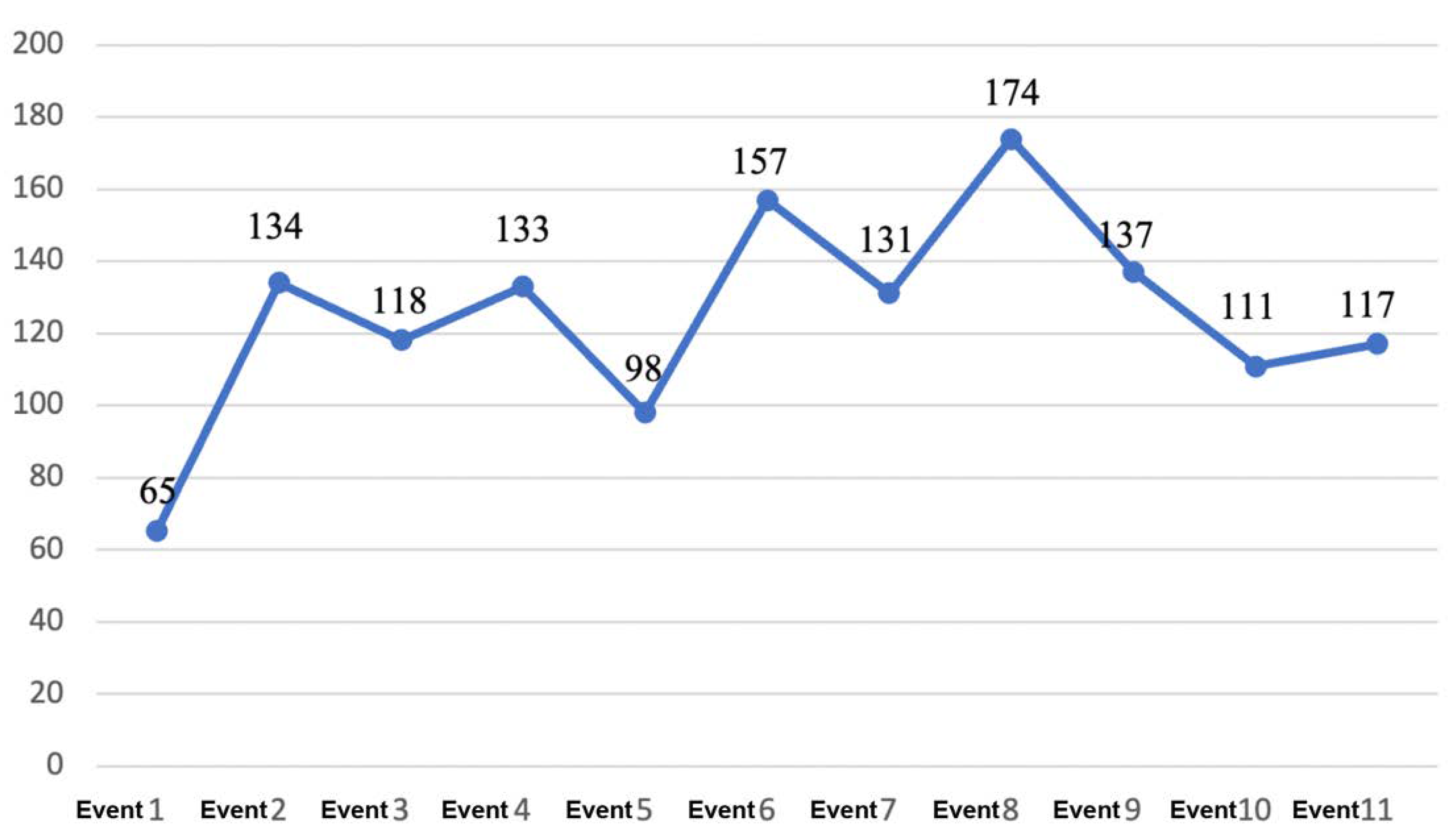

4.3. Preferences and Experience Designs of the Research Event

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

- We conducted a questionnaire survey to examine the effects that the experience designs of festive events have on cultural emotion, travel motivation, and behavioral intention. The goodness-of-fit results verified the feasibility of the proposed Festival Experience Design Influence Model and its value for future research and applications.

- The experience designs examined in this study significantly and positively influenced the respondents’ cultural emotions and travel motivations. However, they did not significantly impact participatory intentions, revisitation willingness, recommendation behavior, and other behavioral intentions, suggesting that, although the event content and implications resonated with the respondents, they did not evoke subsequent behaviors. This conclusion reflects the behavioral intentions at the outermost layer of the conceptual map proposed in this study. It suggests that experience designs alone are unlikely to prompt people to overlook their cultural emotions and travel motivations and directly enter decision-making behaviors. Bastiaansen et al. [60] and Rodríguez-Campo et al. [61] mention that events must be designed in such a way that they resonate with people emotionally in order to evoke behavioral shifts. The results show that cultural emotion significantly and positively influenced the respondents’ travel motivations and behavioral intentions, suggesting that attractive, people-centered, and highly relatable events satisfied participants’ physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization needs and, consequently, evoked their participatory intentions, revisitation willingness, recommendation behavior, and other behavioral intentions. The results also show that cultural emotion mediated the relationship between experience design and travel motivation and between experience design and behavioral intention, suggesting that the culture and emotion of festive events are unique and necessary and impact participants’ participatory intentions and behaviors.

- The results indicated that the respondents most preferred the hybrid events for entertainment and aesthetics and that both the in-person and virtual events contained educational elements. The primary reasons for the high scores in the education construct for the virtual events were the ease of access via smartphone, ease of application, and personal interaction. By comparison, the main reason for the low scores in the education construct for the in-person events was that learners are easily distracted in in-person events.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Getz, D. Event Management and Event Tourism; Cognizant Communication Corporation: Putnam Valley, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Derrett, R. Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a community’s sense of place. Event Manag. 2003, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Whitford, M. An exploration of events research: Event topics, themes and emerging trends. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2013, 4, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, L.F.; Nijkamp, P. (Eds.) Cultural Tourism and Sustainable Local Development. Farnham; Ashgate: England, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.B. The service experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.O.N.A.L.D.; Frisby, W.E.N.D.Y. Developing a municipal policy for festivals and special events. Recreat. Can. 1991, 19, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrozy, U. Marketing of tourism: A paradigm shift toward sustainability. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2007, 1, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Voogd, H. Selling the City: Marketing Approaches in Public Sector Urban Planning; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

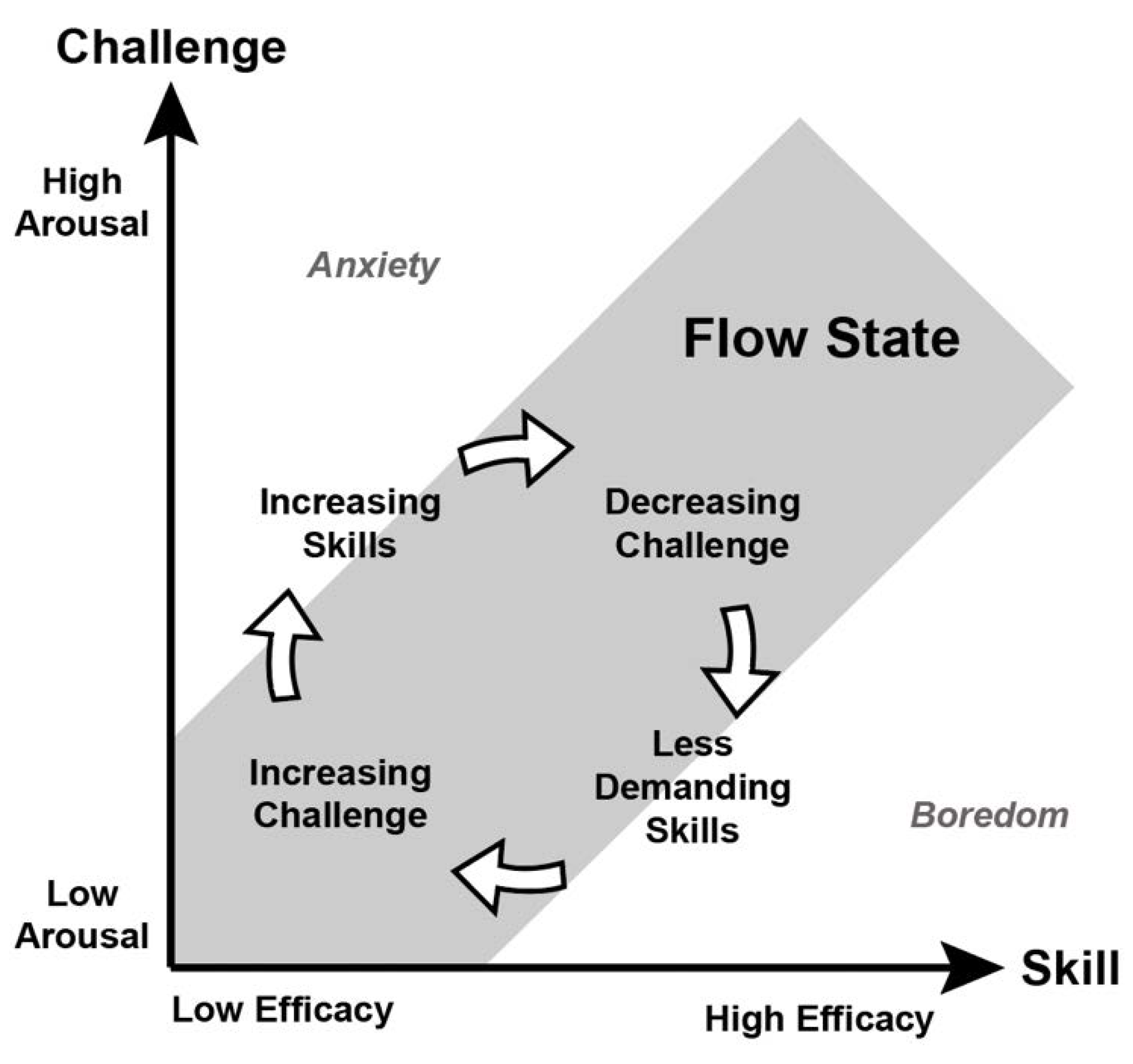

- Mihaly, C.M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.S. Persuasive histories: Decentering, recentering and the emotional crafting of the past. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2002, 15, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaett, V. Exploring the On-Site Behavior of Attendees at Community Festivals a Social Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Girish, V.G.; Chen, C.F. Authenticity, experience, and loyalty in the festival context: Evidence from the San Fermin festival, Spain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre and Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

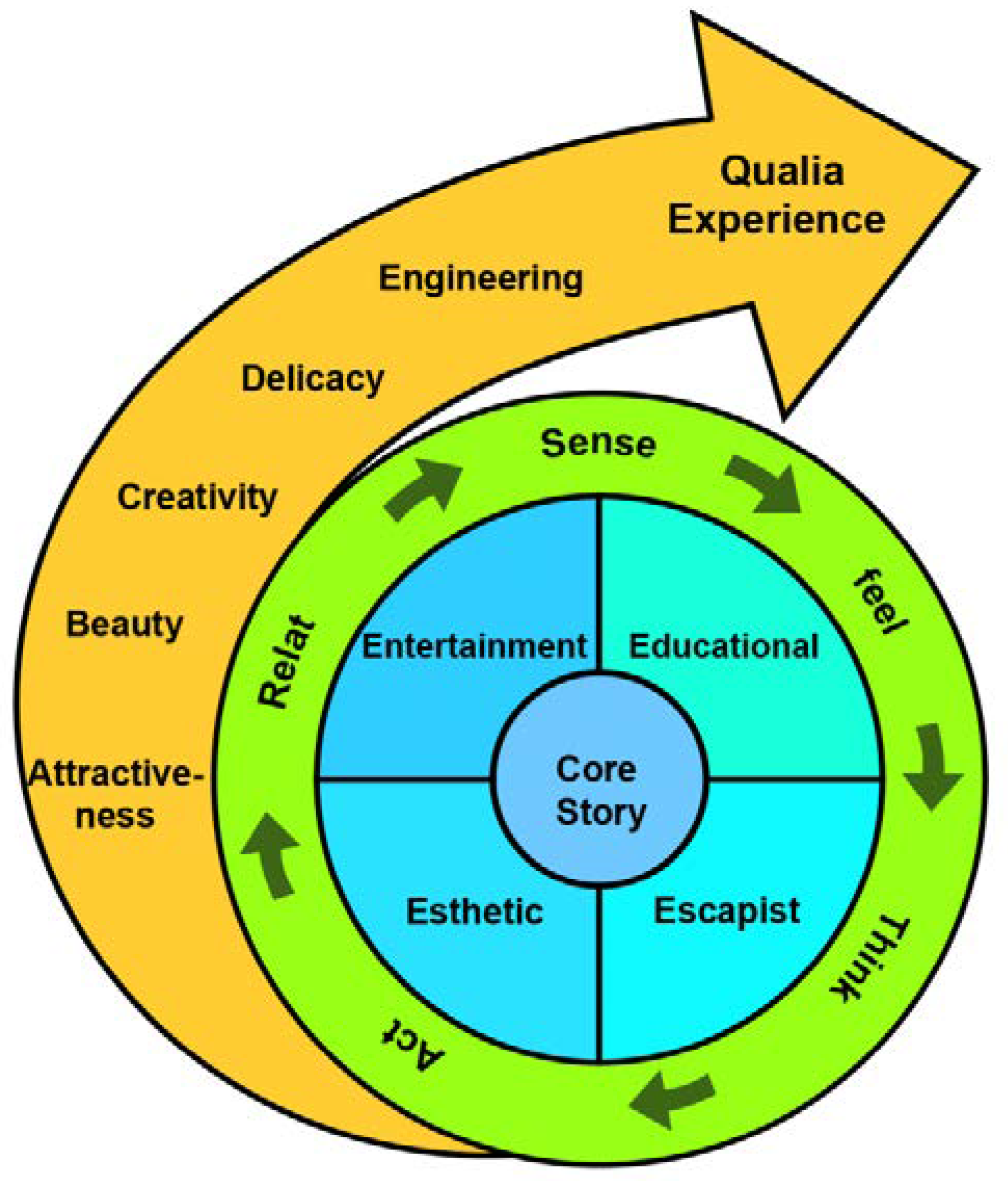

- Lin, R.T. From service innovation to qualia product design. J. Des. Sci. 2011, 14, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, A. The Transformative Power of Memory. In Memory and Change in Europe: Eastern Perspectives; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Erll, A. Locating family in cultural memory studies. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2011, 42, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C. Cultural Nostalgia:Emotional Dimensions of Cultural Memory. Acad. J. Ournal. Zhongzhou 2015, 7, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Choi, D. Designing emotionally evocative homepages: An empirical study of the quantitative relations between design factors and emotional dimensions. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 899–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Research on TV Programs of Cultural Emotions by Mass Media. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Woodside, A.G.; Lysonski, S. A general model of traveler destination choice. J. Travel Res. 1989, 27, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Fyall, A.; Gilbert, D.; Wanhill, S. Tourism: Principles and Practice; Pearson: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Visitors’ emotional responses to the festival environment. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Chang, P.S. Examining the relationships among festivalscape, experiences, and identity: Evidence from two Taiwanese aboriginal festivals. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Chang, Y.S. The influence of experiential marketing and activity involvement on the loyalty intentions of wine tourists in Taiwan. Leis. Stud. 2012, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.; Pigram, J.J. Recreation specialization reexamined: The case of vehicle-based campers. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.E.; Dimanche, F. Leisure involvement revisited: Conceptual conundrums and measurement advances. J. Leis. Res. 1997, 29, 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.G.; Shaw, S.M.; Havitz, M.E. Men’s and women’s involvement in sports: An examination of the gendered aspects of leisure involvement. Leis. Sci. 2000, 22, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.L.; Graefe, A.R. Attachments to recreation settings: The case of rail-trail users. Leis. Sci. 1994, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. Effects of place attachment on users’ perceptions of social and environmental conditions in a natural setting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.P.; Alexander, P.A. A motivated exploration of motivation terminology. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 3–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E. Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Ann. Tour. Res. 1982, 9, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E.; Park, C.J. Leisure-related social support and self-determination as buffers of stress-illness relationship. J. Leis. Res. 1996, 28, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L. Leisure and the Internet. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 1999, 70, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Preface to Motivation Theory. Psychosom. Med. 1943, 5, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, N.P.; Ellis, G.D. Traveler types and activation theory: A comparison of two models. J. Travel Res. 1991, 29, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.W.; Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.B. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P. The Ulysses Factor: Evaluating Visitors in Tourist Settings; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J.F.; Roger, D. Consumer Behavior; The Dryden Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.H. Implementing the “Marketing You” project in large sections of principles of marketing. J. Mark. Educ. 2004, 26, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.O.; Sasser, W.E. Why satisfied customers defect. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, V.S. Recent attribution research in consumer behavior: A review and new directions. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 14, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Q. Research on Marketing Public Relations Strategy of Folk Festival Activities-Take “Hello! Love City Tainan Chihsi Festival “ as an Example. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tainan Chihsi Festival Facebook. 2021. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/love.tncity (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- PIXNET. Network Critical Report. 2014. Available online: https://www.gvm.com.tw/article/27436 (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Factor Analysis. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 3, pp. 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A.; Long, J.S. (Eds.) Testing Structural Equation Models; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mardia, K.V.; Foster, K. Omnibus tests of multinormality based on skewness and kurtosis. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1983, 12, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunch, N. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling Using IBM SPSS Statistics and AMOS; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaansen, M.; Lub, X.D.; Mitas, O.; Jung, T.H.; Ascenção, M.P.; Han, D.I.; Moilanen, T.; Smit, B.; Strijbosch, W. Emotions as core building blocks of an experience. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Campo, L.; Alén-González, E.; Antonio Fraiz-Brea, J.; Louredo-Lorenzo, M. A holistic understanding of the emotional experience of festival attendees. Leis. Sci. 2022, 44, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Name | Type | Introduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cloud Lovers | Virtual | A virtual chatbot created for the Tainan Chihsi Festival. Join the official Line Account and chat with someone in the Showa Era! |

| 2 | Online Tribute to Yue Lao | Virtual | Access the event page through the Official Line account and pay tribute to seven major Yue Lao Temples remotely. Send your wishes directly from your phone. A temple representative performs the matchmaking ceremony for you and provides you with your fortune. |

| 3 | Searching for Lovers of Showa | Virtual | Access the event page through the Official Line account. There are six chapters: Encounter, Longing, Acquaintance, Admiration, Adoration, and Love. Each chapter contains several multiple-choice questions. Once complete, the system will match you with someone from the Showa Era based on your responses. |

| 4 | Old School Date Day | In-person | This event will be held over a weekend. It features a retro market, games, outdoor cinema, musical performances, and bumper cars, taking you back to the markets of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. |

| 5 | Installation Art | In-person | A number of exclusive installation artworks will be displayed at the Blueprint Cultural and Creative Park. The two main attractions, Love Wall and Say I Love You, will bombard your romantic senses with video, audio, and text. |

| 6 | Old School Date Special Exhibition | In-person | The exhibition displays popular dating venues in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, including clothing stores, salons, transport stations, and restaurants. Come and enjoy a retro experience. |

| 7 | Collecting Love Notes | In-person | Visit designated stores and purchase specific items or spend a specific amount to receive a Love Note (10 in total). Collect any two to redeem a limited edition “Modern Love x Vaccine” Souvenir. |

| 8 | Discount Coupons | Hybrid | Enter the merchant number into the official Line Account to receive electronic coupons for all participating stores. |

| 9 | Matchmaking Raffle | Hybrid | A joint event between Line Point and local Tainan vendors. Users can access the raffle page between 09:00 and 00:00 via the official Line Account. |

| 10 | EAT, DATE, LOVE | In-person | Spend NT 3320 or more at designated restaurants for the chance to partake in the hotel commemorative photo event. |

| 11 | HSR Hotel Discounts | In-person | Purchase selected hotel packages during the event to receive hotel and HSR discounts. |

| Dimension | Code | Item | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience Design | Entertainment | Ent1 | The content of this festival event feels fascinating. |

| Ent2 | The content of this festival event is interesting. | ||

| Ent3 | The content of this festival event is fun. | ||

| Educational | Edu1 | This festival evokes a sense of learning. | |

| Edu2 | This festival gives me culture-specific knowledge. | ||

| Edu3 | This festival event piqued my curiosity to learn about this culturally relevant thing. | ||

| Esthetic | Est1 | The content of this festival event is well designed. | |

| Est2 | The visual aesthetic of this festive event design is great. | ||

| Est3 | The concept and value of this festival event attract me very much. | ||

| Escapist | Esc1 | This festival event feels like you can play a different role. | |

| Esc2 | This festival event takes people out of the ordinary life situation. | ||

| Esc3 | This festival event feels as if you are in another time and place. | ||

| Cultural Emotion (Involvement, Place Attachment) | Attraction | Att1 | I am interested in taking part in the festive event. |

| Att2 | This festive events make me happy. | ||

| Att3 | It is very important for me to attend this festive event. | ||

| Centrality | Cen1 | I found that my life is intertwined with this festive event. | |

| Cen2 | I enjoy talking about this festive event with my friend. | ||

| Cen3 | My friends and I like to go to this festive event often. | ||

| Self-Expression | Exp1 | I am able to inform others about this festive event. | |

| Exp2 | This festive event makes it possible for me to express my own style. | ||

| Exp3 | When I attended this festive event, I was glad that other people saw me. | ||

| Place Dependence | Rel1 | I prefer going to this place rather than other tourist attractions. | |

| Rel2 | This festival gives me a greater sense of satisfaction compared with other festivals. | ||

| Rel3 | This festival cannot be replaced by other festival-based tourism. | ||

| Place Identity | Ide1 | This festive event means so much for me. | |

| Ide2 | I strongly identify with this festive event. | ||

| Ide3 | I feel like I belong to this festive event. | ||

| Travel Motivation | Physiological | Phy1 | The festival event allowed me to have a unique experience and satisfied my curiosity. |

| Phy2 | This festival event showed me some historical outfits. | ||

| Phy3 | This festival event gives me the opportunity to learn about and discover traditional culture. | ||

| Safety | Safe1 | The safety of this festive event will have a bearing on my desire to travel. | |

| Safe2 | This festive event enables me to travel in a casual environment. | ||

| Safe3 | As a participant in this festival event, I feel safe. | ||

| Love and Belonging | Soc1 | This festival event is my chance to engage with people and meet new friends. | |

| Soc2 | This festival gives me the opportunity to express my ideas and expertise to other people. | ||

| Soc3 | This festival event makes it possible for me to win the respect of others. | ||

| Esteem | Res1 | This festive event can satisfy my aesthetic research and learning new knowledge. | |

| Res2 | This festival gave me an opportunity to get to know myself better. | ||

| Res3 | This festival event lets me realize personal fulfillment and prestige. | ||

| Self- Actualization | Self1 | This festive event calms, calms or releases the person’s emotional level. | |

| Self2 | This festive event increases personal capacity and vision. | ||

| Self3 | This festival helps me to reduce mental stress, stress and frustration. | ||

| Behavioral Intention | Intention to Participate | Int1 | I went to this festival because I love the culture. |

| Int2 | I will purchase products related to this festival event. | ||

| Int3 | I’ll be looking for information on this festival event. | ||

| Repeated Behavior | Rep1 | I’m getting back to this festival event. | |

| Rep2 | I will again purchase the products associated with this festival event. | ||

| Rep3 | I’m prepared to pay more for this festival event. | ||

| Suggestive Behavior | Rec1 | I would recommend this festival event to anyone else. | |

| Rec2 | I want everyone to know that I took part in this festival event. | ||

| Rec3 | I will be encouraging my friends to attend this festival event. | ||

| Dimension | M | SD | SK | KU | SFL | SMC | EV | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience Design | 0.876 | 0.639 | |||||||

| Entertainment | 5.990 | 0.784 | −0.577 | −0.312 | 0.745 | 0.555 | 0.271 | ||

| Educational | 5.340 | 1.029 | −0.325 | −0.524 | 0.850 | 0.722 | 0.298 | ||

| Esthetic | 5.983 | 0.839 | −0.764 | −0.144 | 0.769 | 0.591 | 0.283 | ||

| Escapist | 5.549 | 0.995 | −0.356 | −0.620 | 0.828 | 0.685 | 0.315 | ||

| Cultural Emotion | 0.946 | 0.779 | |||||||

| Attraction | 5.583 | 0.964 | −0.392 | −0.532 | 0.877 | 0.770 | 0.215 | ||

| Centrality | 5.248 | 1.157 | −0.365 | −0.537 | 0.866 | 0.749 | 0.338 | ||

| Self-Expression | 5.362 | 1.071 | −0.256 | −0.792 | 0.890 | 0.793 | 0.240 | ||

| Place Dependence | 5.241 | 1.152 | −0.438 | −0.425 | 0.894 | 0.800 | 0.269 | ||

| Place Identity | 4.954 | 1.223 | −0.179 | −0.754 | 0.885 | 0.784 | 0.328 | ||

| Travel Motivation | 0.937 | 0.748 | |||||||

| Physiological | 5.740 | 0.947 | −0.515 | −0.444 | 0.826 | 0.682 | 0.279 | ||

| Safety | 5.515 | 0.998 | −0.331 | −0.406 | 0.839 | 0.703 | 0.298 | ||

| Love and Belonging | 5.189 | 1.171 | −0.251 | −0.568 | 0.877 | 0.769 | 0.320 | ||

| Esteem | 5.211 | 1.088 | −0.146 | −0.727 | 0.911 | 0.829 | 0.205 | ||

| Self-Actualization | 5.385 | 1.101 | −0.310 | −0.453 | 0.868 | 0.754 | 0.301 | ||

| Behavioral Intentions | 0.935 | 0.827 | |||||||

| Intention to Participate | 5.218 | 1.171 | −0.445 | −0.213 | 0.928 | 0.862 | 0.191 | ||

| Repeated Behavior | 5.028 | 1.197 | -−0.243 | −0.539 | 0.944 | 0.891 | 0.158 | ||

| Suggestive Behavior | 5.501 | 1.080 | −0.460 | −0.236 | 0.854 | 0.730 | 0.319 | ||

| Mardia | 100.087 | p(p + 2) = 17(17 + 2) = 323 | |||||||

| Dimension | Number of Items | Correlation Coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience Design | Cultural Emotion | Travel Motivation | Behavioral Intentions | ||

| Experience Design | 4 | 0.799 | |||

| Cultural Emotion | 5 | 0.805 ** | 0.882 | ||

| Travel Motivation | 5 | 0.793 ** | 0.850 ** | 0.865 | |

| Behavioral Intentions | 3 | 0.729 ** | 0.838 ** | 0.856 ** | 0.910 |

| Variable | Path Coefficient | CR | p | Hypotheses Verification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Experience Design -> Cultural Emotion | 0.91 | 16.560 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | Experience Design -> Travel Motivation | 0.44 | 3.579 | *** | Supported |

| H3 | Experience Design -> Behavioral Intentions | −0.30 | −2.180 | * | Not supported |

| H4 | Cultural Emotion -> Travel Motivation | 0.50 | 4.137 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | Cultural Emotion -> Behavioral Intentions | 0.52 | 4.079 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | Travel Motivation -> Behavioral Intentions | 0.70 | 6.386 | *** | Supported |

| H7 | Experience Design -> Cultural Emotion -> Travel Motivation | 0.44 + (0.91 × 0.50) = 0.44 + 0.45 = 0.89 > 0.44 | Supported | ||

| H8 | Experience Design -> Cultural Emotion -> Behavioral Intentions | −0.30 + (0.91 × 0.52) = −0.30 + 0.47 = 0.17 > −0.30 | Supported | ||

| Experience Factor | Source of Variation | SS | DF | MS | F | Type | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entertaining | Between groups | 13.8 | 2 | 6.90 | 10.87 *** | Virtual | 5.65 | 0.77 |

| Within groups | 451.2 | 711 | 0.64 | In-person | 5.84 | 0.83 | ||

| Total | 465.0 | 713 | Hybrid | 5.99 | 0.78 | |||

| Educational | Between groups | 31.4 | 2 | 15.70 | 18.31 *** | Virtual | 5.25 | 0.92 |

| Within groups | 610.0 | 711 | 0.86 | In-person | 5.17 | 1.03 | ||

| Total | 641.4 | 713 | Hybrid | 4.77 | 0.82 | |||

| Aesthetic | Between groups | 9.6 | 2 | 4.82 | 7.437 ** | Virtual | 5.78 | 0.78 |

| Within groups | 460.8 | 711 | 0.65 | In-person | 5.70 | 0.80 | ||

| Total | 470.5 | 713 | Hybrid | 5.98 | 0.84 | |||

| Escapist | Between groups | 3.4 | 2 | 1.68 | 1.846 | Virtual | 5.41 | 0.91 |

| Within groups | 647.9 | 711 | 0.91 | In-person | 5.40 | 0.96 | ||

| Total | 651.2 | 713 | Hybrid | 5.55 | 0.99 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yen, H.-Y. How the Experience Designs of Sustainable Festive Events Affect Cultural Emotion, Travel Motivation, and Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911807

Yen H-Y. How the Experience Designs of Sustainable Festive Events Affect Cultural Emotion, Travel Motivation, and Behavioral Intention. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):11807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911807

Chicago/Turabian StyleYen, Hui-Yun. 2022. "How the Experience Designs of Sustainable Festive Events Affect Cultural Emotion, Travel Motivation, and Behavioral Intention" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 11807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911807

APA StyleYen, H.-Y. (2022). How the Experience Designs of Sustainable Festive Events Affect Cultural Emotion, Travel Motivation, and Behavioral Intention. Sustainability, 14(19), 11807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911807