Decoding Collective Action Dilemmas in Historical Precincts of Delhi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cultural Heritage as “Common Goods”

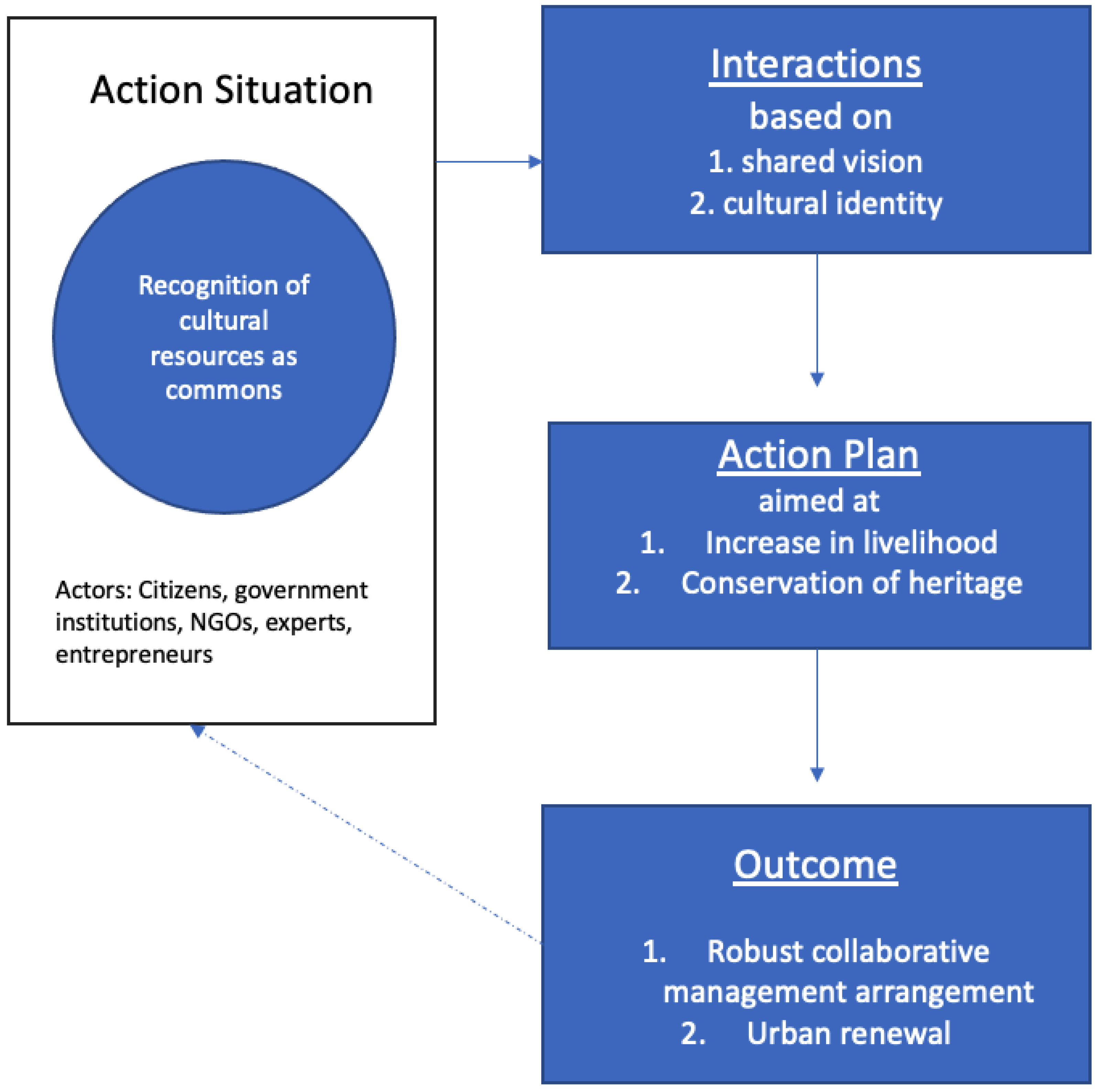

3. Application of the IAD-NAAS Framework

3.1. Overview of Nizamuddin Basti

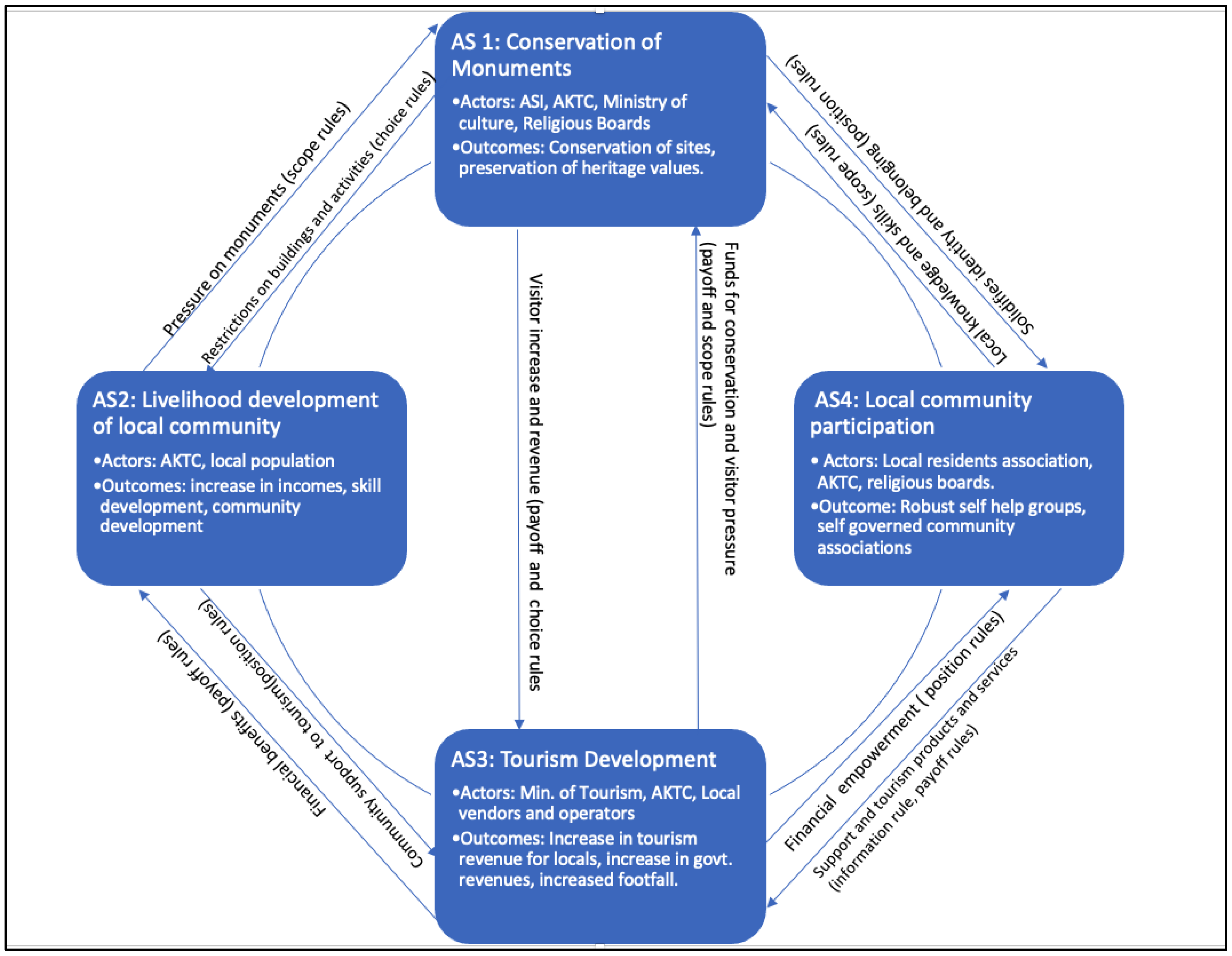

3.2. Action Situations in Nizamuddin Basti

4. Conclusions and Way Further for Collaborative Decision-Making

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertacchini, E.; Gould, P. Collective Action Dilemmas at Cultural Heritage Sites: An Application of the IAD-NAAS Framework. Int. J. Commons 2021, 15, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, C.; Ostrom, E. Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M.D. Networks of Adjacent Action Situations in Polycentric Governance: McGinnis: Adjacent Action Situations. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.C.; Andersson, K.; Ostrom, E.; Late, E.E.; Shivakumar, S. The Samaritan’s Dilemma: The Political Economy of Development Aid; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, E.M.; Brondizio, E. Problem Framing Influences Linkages Among Networks of Collective Action Situations for Water Provision, Wastewater, and Water Conservation in a Metropolitan Region. Int. J. Commons 2020, 14, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Cultural Capital. J. Cult. Econ. 1999, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P.G. Considerations on Governing Heritage as a Commons Resource. In Collision or Collaboration; Gould, P.G., Pyburn, K.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, C. Research on the Commons, Common-Pool Resources, and Common Property; Digital Library of the Commons: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2006; Available online: https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/contentguidelines (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Hess, C. Mapping the New Commons. In Proceedings of the 2th Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons, University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham, UK, 14–18 July 2008; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Di Girasole, E.G.; Daldanise, G.; Clemente, M. Strategic Collaborative Process for Cultural Heritage. New Metrop. Perspect. 2018, 101, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, E. Residents’ Motivations to Participate in Decision-Making for Cultural Heritage Tourism: Case Study of New Delhi. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacchini, E.E.; Bravo, G.; Marrelli, M.; Santagata, W. Cultural Commons: A New Perspective on the Production and Evolution of Cultures; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work; Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The Council of European Union. Council Conclusions on Participatory Governance of Cultural Heritage. 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014XG1223&from=EN (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Iaione, C.; De Nictolis, E.; Santagati, M.E. Participatory Governance of Culture and Cultural Heritage: Policy, Legal, Economic Insights from Italy. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 777708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P.G. Privatization, Public-Private Partnerships, and Innovative Financing for Archaeology and Heritage. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. New World Heritage Sites 2019; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/review/94/ (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Sharma, J.P. The South Asian Shahar: Reimagining Shahariyat as urban heritage. In Cultural Landscapes of South Asia; Silva, K.D., Sinha, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schlager, E.; Ostrom, E. Property-Rights Regimes and Natural Resources: A Conceptual Analysis. Land Econ. 1992, 68, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; Available online: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691122380/understanding-institutional-diversity (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aga Khan Development Network. Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative: Annual Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.nizamuddinrenewal.org/assets/images/Annual-report-2020.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Aga Khan Development Network. Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative, Annual Report 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.nizamuddinrenewal.org/assets/images/Nizamuddin-Urban-Renewal-Inititiave_Annual-Report-2019.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2022).

| Actor | Objectives | Generic Action Situations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assignment/Appropriation | Provision/Production | Financing | Rule Making | Monitoring | Coordination and Dispute Resolution | ||

| UNESCO | Preserve OUV (Outstanding Universal Value (OUV): The preamble of the World Heritage Convention on the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) says “that parts of the cultural and natural heritage are of outstanding interest and therefore need to be preserved as part of the world heritage of mankind as a whole” [19]) and enhance WHS (World Heritage Sites (WHS)) Brand thru Master Plan approval and review process | Create master plans/guidelines for WHS site-place restrictions on consumption and appropriation of WHS heritage sites. | NA | Provide international fund (often limited) | Make rules and regulations to be followed by state parties to maintain the OUV status of the monument | Regular assessment of WHS site compliance/listing or delisting of sites from OUV status. | NA |

| ASI (Archaeological Survey of India) | Primary national agency to conserve heritage sites and enforce regulations. | Regulate use of heritage and area surrounding it | Fund conservation projects | Allocate revenue among tasks involved for management of sites (protection, conservation, license, tourist facilities etc.,) | Create formal codes, laws, and rules for conservation and management for all government protected monuments in the country. | Monitor and enforce provisions of AMASR Act (The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (AMASR Act) 1958) and other regulation | Interface between national/state governments and experts/UNESCOCoordinate with law enforcement agencies (typically the local police station) to resolve dispute or punish violation of provisions of AMASR act. |

| AKDN | preservation, socio-cultural development, urban regeneration | Financial and/or technical support for conservation, socio-cultural development, urban regeneration | Contribute/Raise funds | Partnership with public bodies to assist on technical expertise, advocacy, organization of self-help groups in the local community. | NA | Advocacy for sustainable development of heritage, socio-economic development of the community. | |

| Local Community/Civil Society Groups | Benefit from tourism (employment and income), improved community infrastructure and services, maintain and promote community values and traditional culture | Assign/regulate local and religious sites for community use, manage informal economic activities within the neighborhood | Develop and maintain traditional art forms and practices, create tourist experience/provide cultural goods and artforms to tourists. | Payment of taxes | Advocate for local community interests/take part in decision making) | Monitoring local neighborhoods and site use especially for non-protected and religious sites. | Advocacy for sites with religious/cultural value, advocacy for decision-making powers. |

| Local government bodies (MCD/CPWD/PWD (Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD)/ Central Public Works Department (CPWD) and Public Works Department (PWD))) | Generate revenue from tourism activities, regulate land use and building activities, provide infrastructural services. | Regulate economic activities, regulate local living conditions and infrastructure | Implement master plans, Fund and oversee implementation of local schemes, | Allocate resources especially taxes and fees among concerned departments and tasks. | Implement local and national regulations, create and implement local land use rules. | Enforce applicable regulations and laws. | Coordinate with law enforcement agencies (typically the local police station) to resolve dispute over local regulations. |

| NGOs and experts | Provide expertise, train experts, partner with government bodies | NA | Provide technical/academic expertise to public bodies or local residents (through organizations of workshops, partnerships etc.,) | Contribute funds/Provide technical/academic expertise | Form advocacy groups for heritage conservation and promotion | NA | Form advocacy groups for heritage conservation and promotion |

| Tourism Industry | Generate tourism revenues, profits and return on their investment | Promote tourism activities and business. | Invest in tourist infrastructure and services | Invest in tourist infrastructure and services | Advocate for interest of business operators and employees in the industry | NA | Advocate for interest of business operators and employees in the industry. |

| Rule | Function |

|---|---|

| Position rules | Create positions for actors (trader/expert/official etc.,) |

| Boundary rules | Define who qualifies to hold certain positions, the process by which positions are assigned and the process to exit the position. |

| Choice rules | Prescribe action choices available for actors in specific positions. |

| Aggregation rules | Decide which players and how many of them can participate in a decision. |

| Information rules | Allow channels of information flows available to participants |

| Payoff rules | Assign rewards or sanctions to actions taken or outcomes |

| Scope rules | Establish the range of possible outcomes (otherwise actors can affect any physically possible outcomes). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chauhan, E. Decoding Collective Action Dilemmas in Historical Precincts of Delhi. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811741

Chauhan E. Decoding Collective Action Dilemmas in Historical Precincts of Delhi. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811741

Chicago/Turabian StyleChauhan, Ekta. 2022. "Decoding Collective Action Dilemmas in Historical Precincts of Delhi" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811741

APA StyleChauhan, E. (2022). Decoding Collective Action Dilemmas in Historical Precincts of Delhi. Sustainability, 14(18), 11741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811741