Abstract

Research suggests that sustainability may not be sufficient to yield a competitive advantage. Building on the resource-based view, this research evaluates three questions: (1) Can using sustainability as a differentiator lead to consumers choosing sustainable products? (2) Does product sustainability appeal more to environmentally concerned consumers? (3) Does product sustainability appeal more when paired with innovation? To test the hypotheses, an online survey of 344 US respondents was conducted. Consumers were given a hypothetical budget for an office chair and asked to choose between two products at a time. Hypotheses were tested with frequency and Chi-square tests and logistic regression. Findings indicate that the innovative product was preferred over the undifferentiated one, but the sustainable product was preferred over both innovative and undifferentiated products. The sustainability–innovativeness bundle was not preferred over the sustainable product. Environmental concern increased preference for the sustainable product over the innovative product, but not over the undifferentiated one. These findings suggest that sustainability is a stronger differentiator than innovation, but that bundling both features does not further enhance product choice. Attitude toward the environment may not predict behavior. Instead, preference for the sustainable product may originate in variety-seeking behavior, with sustainability seen as an innovation.

1. Introduction

Recent work (e.g., [1]) suggests that sustainability, by itself, may not be enough to yield a competitive advantage for business: While customers might approve of sustainability in general, they are not necessarily willing to choose sustainable products for themselves if the only distinguishing feature of the sustainable product is its sustainability. In fact, sustainability is sometimes believed to erode profitability, rather than support it. The perceived tension between sustainability and profitability has traditionally created a reluctance among businesses to engage in sustainability initiatives. As a result, consumer choice and opportunity to engage in sustainable consumption behaviors are constrained.

To enable the co-creation of sustainable consumption behaviors, the sustainable product must first exist and the company must communicate and market the sustainable features of its goods or services to consumers [2]. Some research suggests that sustainability can be a competitive advantage, but it is not automatically one [1]. Building on the resource-based view and the resource management perspective [3,4,5,6,7], and on evidence that the engagement strategy drives the success of such ventures [8], this study thus sets out to empirically evaluate three questions: (1) Can a firm’s use of sustainability as a competitive advantage (e.g., by differentiating on the basis of a sustainable design feature) lead to consumers choosing the firm’s sustainable products? (2) Does sustainability as a product feature appeal more to consumers who identify themselves as concerned about the natural environment? (3) Is having a sustainability focus more successful in winning over consumers if it is paired with innovation?

This research thus investigates two potential reasons to buy innovative and sustainable (i.e., circular) product features, individually and together, and the strength of their influence on consumers’ product preference, relative to an undifferentiated product. Given that e-commerce has increased substantially in recent years, the effect of different product attribute emphasis (sustainability vs. innovation) on consumers’ product preference in a virtual (online) format is considered alongside the impact of bundling innovation and sustainability competencies as an opportunity for improved product performance. We thus also apply the resource-based view of the firm and the resource management perspective that such bundling creates value for the customer. Finding that the bundle is more successful than the individual competencies would offer an inherent justification for companies to pursue sustainable innovation as called for by [9].

1.1. Sustainability, Innovation, and Competitive Advantage

Sustainability has historically been, and is still often treated as, a dimension of corporate social responsibility (CSR), and there is consistent evidence across decades that CSR does help financial performance [10,11,12]. Sustainability, in itself, may not constitute a competitive advantage, but as an element of CSR, it could differentiate a company’s products and provide competitive advantage—if implemented and performed right [8,13]. While we expect that sustainability can be a competitive advantage, if approached correctly and marketed to people who care about the environment, we follow the resource-based view and the resource management perspective in predicting that it will be more effective if bundled with another capability. Innovation, a major driver of consumer behavior [14], is correlated with CSR [15,16,17,18] and has been found to affect and even overshadow the CSR–financial performance relationship [10,15,19]. Sustainability can and probably should shape innovation as well [20], and as such, it makes sense to expect innovation to play a role in sustainability and to affect consumer choice and, consequently, firm success.

Sustainability is distinguished from observable product innovation in that the sustainability attribute of the product often originates from the use of new materials, production process, or design, and, therefore, may not be directly observable, easily communicated, or valued by consumers and other stakeholders [17,18,19,21]. Despite evidence that individuals are rarely willing to sacrifice for the greater good [18], and that sustainability in and of itself may not be sufficient to provide a competitive advantage [1], sustainability issues, including climate change and pollution, have grown increasingly urgent in the minds of consumers [13,21,22,23]. In the case of the fashion sector, [20] noted that although there is general improvement in cognitive and affective awareness of sustainability, this does not translate into aligned purchase behavior. Consumers may regard sustainability as a social good; despite a lack of immediate individual benefit, this differentiating feature may lead them to choose to buy it [13,24,25], particularly in the absence of innovation or other reasons to choose the competition’s products [10]. Reference [26] found that consumers prefer sustainable products over non-sustainable ones when they are aware of the difference between the two. They also conclude that many customers are not aware of the difference because most consumers do not spend time reading product labels [26].

The resource-based view and the resource management perspective suggest that a firm might be able to bundle sustainability and innovation together in a way that makes a stronger competitive advantage than either alone [3,5,6,7,27]. Similarly, sustainability initiatives may require significant innovation [9]. A recent meta-analysis [28] confirms that green innovation helps firm performance and that it helps firm performance more in industries closest to consumers. For consumers, green innovation may alleviate the perceived tension that they must choose between sustainability and innovation. Exploring the same relationship from a different perspective, [29] found that sustainable innovation efforts within supply chains can be motivated by changes in consumer preference characteristics. Recent theory regarding the possibility of sustainability as a competitive advantage suggests that sustainable innovation may be the driver of the success of a sustainable firm [1,25]. This is consistent with the arguments of [1], who suggest that sustainability is not necessarily sufficient to overcome product weaknesses such as reduced functionality; with the findings of [30] that consumers show little response to sustainability alone; and with the principles of remanufacturing, which yields a product that is sustainable and also of equal or greater value than the non-sustainable alternative [31,32]. Accordingly, this work is focused on exploring whether the bundling of sustainability with innovation to create a stronger competitive advantage is likely to make the sustainable product more competitive than a sustainable product that does not also have the benefit of innovation.

1.2. Operationalizing Circular Economy and Sustainability at the Product-Level

We align this work with the ongoing, scholarly discussion of how circular economy (CE) and sustainability are related (c.f., [33,34]), which proposes that circular economy is a path to sustainability that can gain broad support from diverse stakeholders by providing them clear benefits. Circular economy is an increasingly popular and potentially successful approach to sustainability that addresses product-, process-, and system-level design interventions to eliminate all forms of waste [32,33,34]. Research into sustainability innovation, such as that required to transition to CE is increasingly focused on advancements in Industry 4.0 and digital transformation technologies that can contribute to the firm’s achievement of its sustainability goals [35], e.g., through the use of blockchain [36], big data applications, and artificial and computational intelligence [37]. However, non-digital sustainability innovations, e.g., those that involve environmentally preferable designs and/or material choices specific to product design, manufacturing, and the product-system, are also important to the discussion. While CE strategies may integrate digital technologies [38,39], there are many critical aspects of product design and product life cycle that affect the overall sustainability of a product [31].

We operationalize sustainability within this study in the form of remanufactured products, a specific product of sustainable consumption approach, and an essential component of a realized CE. Product remanufacturing is a standardized industrial process which greatly reduces the environmental impact of the product, while maintaining as-new product performance. The International Resource Panel [32] (p. 16) defines remanufacturing as a: “process of disassembling, cleaning, inspecting, repairing replacing, and reassembling the components of a part or product in order to return it to ‘as-new’ condition”. Remanufacturing enables the extension of product life, closed-loop material flows, and reduced total material consumption and it is one of the more broadly adopted cleaner production strategies alongside other value-retention processes that include repair, refurbishment, and reuse [33].

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents an overview of key gaps in the literature and the hypotheses developed from these; Section 3 introduces the survey method that was used to test and evaluate these hypotheses; Section 4 presents findings based on appropriate analytical methods; Section 5 presents a discussion of the theoretical and practical implications of this work, alongside a reflection on the limitations of this study and areas for future research.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. The Effect of Sustainability on Consumer Intention to Purchase

Consumer intention to purchase is extensively explored in the literature as an important element determining customer behavioral intentions [40]. Purchase intention is believed to be a personal behavior that can be influenced, e.g., with technical or emotional information regarding a product [41]. The role of a firm’s reputation and the trust that a consumer has in that firm have also been found to influence purchase intention [42]. Accordingly, product information and knowledge sharing, such as a product’s sustainability or innovative qualities, may have a demonstrated impact on a consumer’s purchase intention [41]. Further, the development of interpersonal trust to facilitate such sharing may be beneficial to a firm’s strategy [42]. In alignment with [43], we consider the consumer to be a person (not a business or entrepreneurial venture) who is engaged in the acquisition of a product that is provided into the marketplace by the firm (supplier). Large companies have been interested in transitioning to CE for some time, but there is a lack of clear business models and other infrastructure adaptations that are needed to operationalize CE [38]. An information campaign might raise consumer awareness of and use of sustainable choices in e-waste disposal [2,40,41]. Moving slightly along the arc of the circular economy, our focus is on consumer intent to purchase a remanufactured product.

As an operationalization of sustainability, remanufacturing enables the extension of product life, closed-loop material flows, and reduced total material consumption and is one of the more broadly adopted cleaner production strategies alongside other value-retention processes that include repair, refurbishment, and reuse [33]. A long-established characteristic of remanufactured products is that they must meet or exceed the quality and performance specifications of the original ‘new’ version, while offering reduced environmental production impacts [44]. However, consumers may not generally understand this feature of remanufacturing; similarly, the current literature suggests that consumers value sustainability, but may be ill-informed about their options [21,22]. Thus, one aspect of this study examines whether sustainability and circular economy (operationalized as a remanufactured product) are attractive enough features for enough buyers to differentiate a company’s products when marketed effectively [13,39,45,46].

In the case of the remanufactured product, if the process is properly understood, potential consumer perception of sacrifice may be alleviated: the sustainable remanufactured product offers the same functionality as the non-sustainable option, with the added benefit of being better for the environment, thus providing greater value [31,33]. We thus predict that:

Hypothesis 1a.

The sustainable (remanufactured) product is preferred over the undifferentiated product.

2.2. The Effect of Innovation on Consumer Preference

The positive impact of innovation upon firm performance has been well-documented in general [22,35] and in the context of corporate social responsibility [8,10,11,15]. The consumer’s perception of product creativity (“Innovation value”) can have a significant positive effect on consumer purchase intentions, more so than other value constructs including price, quality, or education [47]. Innovation can take place at both product- and process-levels. While product innovation that results in increased functionality, capacity, etc., is typically the more familiar concept for consumers, much of the industry transformation for CE is grounded in process innovation, in which our ways of making and using are being adapted, streamlined, and connected into circular, or at the least, cascading resource flows [32]. While a few studies consider the effects of innovation at the brand level, more study is needed, particularly in terms of the effects at the brand level of consumer perception of sustainability [24]. We help address this need by comparing an innovative product against non-innovative products to see how innovation affects consumer perceptions of and response to a product. From a resource-based view, innovative products, by virtue of being valuable, rare, and unavailable from the competition [48,49], generate increased sales. Given that competitive advantages erode over time [48,49,50], innovating by whatever means possible to generate new competitive advantages appears to be a requirement for long-term survival [14]. This reasoning is consistent with considerable prior evidence that innovation helps performance, so we consider this hypothesis to be straightforward:

Hypothesis 1b.

The innovative product is preferred over the undifferentiated product.

2.3. The Effects of Innovation vs. Sustainability on Consumer Preference

We found very little recent literature on innovation versus sustainability as a source of competitive advantage—most current studies on innovation and sustainability appear to focus on eco-innovation or green innovation. While this is laudable, given the importance of green innovation to the future of humanity, we think it is important to consider the question of how effective innovations that are not sustainable are as competitors against sustainable ones. Given recent arguments that sustainability by itself may not be sufficient to provide a competitive advantage [1], innovation distinct from green innovation seems the logical alternative that might keep consumers from choosing the sustainable product.

Innovation’s well-established effect on financial performance [14,51] has been found to be a sufficiently strong predictor of performance to eclipse the effects of CSR [10,15,19]. A logical interpretation of these findings is that if you are going to choose one supplier, innovation is typically a more powerful reason than sustainability. As such, while either sustainability or innovation alone might attract customers from undifferentiated offerings, when both are available at the same time, it is expected that innovation will beat sustainability in the marketplace. What is true of CSR in general may not be true of sustainability specifically, but the evidence supports the expectation that innovation beats sustainability in the marketplace. Thus:

Hypothesis 1c.

The innovative product is preferred over both the sustainable product and the undifferentiated product.

2.4. The Effects of Combined Sustainability and Innovation on Consumer Preference

The bundling of valued characteristics such as innovation and sustainability may also benefit the company by protecting it against imitation by its rivals, as the more complex the bundle of resources and capabilities used to build a core competency is, the harder it is for rivals to replicate or find substitutes for it [3,5,6,7,27]. As noted by [29], consumers with strong preferences for green products may experience weaker reference price effects when making decisions about purchasing green products. Effectively, this type of consumer may be more willing to purchase such products and even pay a premium for them [29], and thus, manufacturers and suppliers provided increased options to share the sustainable innovation costs in pursuit of associated supply chain efficiency.

Thus, for multiple reasons, we expect that a product that is both innovative and sustainable will be preferred to a sustainable product with no additional differentiating features.

Hypothesis 1d.

The bundled sustainable and innovative product is preferred over the sustainable product.

2.5. Consumer Concern about the Environment

While the general consumer population has not shown a strong preference for sustainable products [30], there are signs that this overall attitude is changing [13,23,25]. While it may not be changing as quickly as some might like among the general population, it has been established that some consumers express a preference for sustainable products and that these consumers are more likely to buy such products [52,53]. However, the relationship between consumer concern about the environment and intention to purchase is complicated [52,53]. The attitude–behavior gap is well-documented, but the literature is conflicting: the most consistent explanatory factor in predicting willingness to pay for sustainable or ‘green’ products is consumer attitude [54], specifically a personal norm of moral obligation [55]. The findings of [53,56] indicate that personality traits and psychological distance play a role in how well concern about the environment affects the intention to buy, and [52] found that general environmental consciousness does not affect the intention to buy sustainable products, though a preference for green products does. Similarly, [23] found that consumers concerned about the environment may be more likely to buy some sustainable products or services than others. When sustainable products are effectively marketed, i.e., through green marketing and the use of clear eco-labels, [57] found that consumer attitudes about the importance of environmental considerations can be positively affected. This suggests that the relationship needs further study, but that consumer attitudes, potentially reflected through stated degree of concern for the environment, alongside other standard purchase intention influences, may influence consumer preference [13,55]. Thus, it is predicted that the more strongly a consumer claims to be concerned about the environment, the more likely that consumer is to prefer sustainable products over other types.

Hypothesis 2a.

Preference for the sustainable product versus the undifferentiated product increases in proportion to the consumer’s stated degree of concern for the environment.

Hypothesis 2b

. Preference for the sustainable product versus the innovative product increases in proportion to the consumer’s stated degree of concern for the environment.

2.6. Variety-Seeking and Preference for Differentiation

Consumers have a wide range of motives to either keep or switch product preferences at repeat decision points; often loyalty to a product is differentiated by utilitarian values, such as price and quality [58,59] and hedonic values that are more subjective and personal [56,60,61]. Fundamental variety-seeking (or variety-avoidance) behavior suggests that individuals can receive (or lose) value just from the act of making a new choice, or ‘switching’ [62]. Variety-seeking behavior can be affected by a wide range of factors ranging from environmental conditions, such as the time of day [63], to the decision maker’s level of knowledge and perceived expertise [64]. This implies that an alignment of preferences over subsequent choices may exist: those who initially prefer the non-traditional product will also prefer the non-traditional product in subsequent product choice pairings. Within the context of CE research, variety-seeking consumers were notably more likely to switch from buying traditional products to buying shared products that existed within more complex, often circular, innovative business models [65]. Thus, we expect that consumers who prefer a differentiated product on one occasion will prefer a differentiated product over a non-differentiated one when choosing again, even if the available differentiation is different the second time.

Hypothesis 3.

Those consumers who initially prefer the sustainable product (vs. undifferentiated product) are more likely to switch to preferring the innovative product (vs. undifferentiated product) when the sustainable product is not offered, as compared to those consumers who had initially preferred the undifferentiated product.

3. Data and Methods

To test the hypotheses regarding consumer preferences for sustainable and innovative product options, an online survey was conducted using a population recruited from across the United States through the Qualtrics consumer panel in June 2016. Qualtrics provides access to qualified target population respondents as specified by the researchers. To ensure similarity to the general population of consumers, quotas were set prior to the beginning of data collection based on age, gender, and geographical region of the respondents. The final sample distribution fairly closely mirrors the overall US population aged 18+ years based on these characteristics. Sample size was selected based on the number of constructs measured, the planned type of the analysis, and the resources available to the authors. Among the survey respondents (n = 344), 50% were female, 16% were 18–24 years, 30% were 25–34 years, 30% were 35–50 years, and 24% were older than 50 years. As a pretest, we conducted an offline survey (n = 106) to ensure that consumer perceptions of price, quality, confidence in evaluation, and comfort were similar across the three different products. This was conducted in person with consumers examining real products as a part of an innovation fair.

Prior to starting the survey, respondents were informed that they had been allocated a budget to cover the cost of an office workspace. It was clearly stated that the budget amount was not coming from their own funds and that it was sufficient to cover the costs of any product being presented to them. With the allocated funds, respondents were required to select their preferred product choice, across a sequence of stated product option scenarios: (1) undifferentiated product vs. sustainable product; (2) undifferentiated product vs. sustainable product vs. innovative product; (3) undifferentiated product vs. innovative product; (4) sustainable product vs. innovative product; (5) sustainable product vs. innovative and non-sustainable product; (6) sustainable product vs. innovative and sustainable product. All participants were presented with the same workspace options and descriptions, and all participants were given the same budget amount. All workspace product options presented the same relative configuration consisting of a work surface, storage, and a task chair.

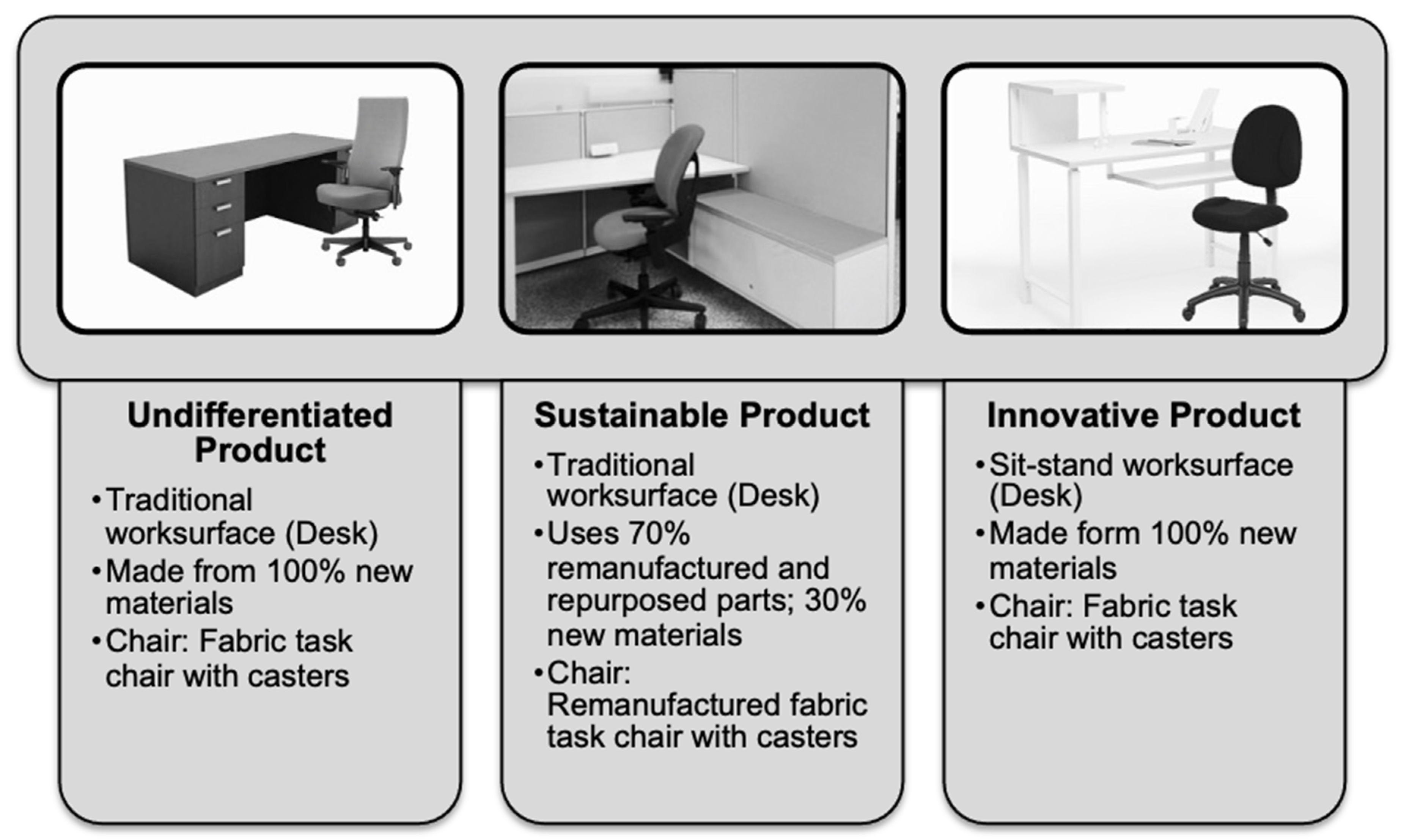

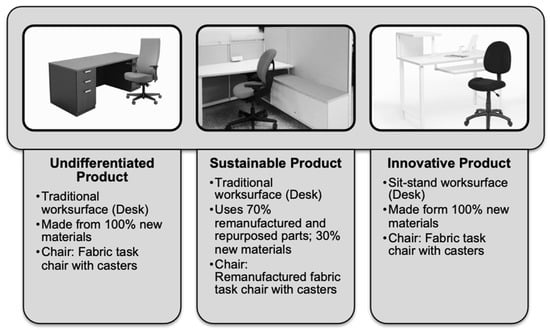

The undifferentiated product option was described as a standard, traditionally manufactured office workspace made from 100% new materials. The innovative product option was described to be a non-traditional, modern design workspace consisting of a work surface that offers observably innovative sitting and standing functionality and a task chair. In this case, the sit–stand workspace was deemed to represent an innovative product option per the previously stated distinction of an observable design innovation that was differentiated from the traditional product design. In describing the sustainable product option, it was specified explicitly that the workspace had been remanufactured. Respondents were further informed that remanufacturing offers an environmentally beneficial impact over traditionally manufactured products. Figure 1 describes the attributes of the products used in the survey. In addition to being provided with this information, respondents were also exposed to color photos of each of the undifferentiated, sustainable, and innovative product options.

Figure 1.

Undifferentiated, Sustainable, and Innovative product descriptions from survey.

Within the survey, respondents were also asked to respond to four questions regarding their personal level of awareness of and concern about issues related to resource depletion and scarcity, environmental degradation, and whether sustainability issues are included in their daily decision making. These four variables were selected due to their relevance to remanufacturing (i.e., the sustainable and innovative product). These self-developed variables were used to capture a single factor for stated level of environmental concern that was related to remanufacturing-specific environmental issues (vs. unrelated environmental issues), using factor analysis (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.87). The items were measured using a Likert-type scale to self-describe importance and concern, (1) = not important/concerned to (5) = very important/concerned:

- How important is [ ] to you in your daily decision making?—Sustainability

- How concerned are you about [ ]?—Resource depletion and resource scarcity

- How concerned are you about [ ]?—Environmental damage from human activity

- How important are the following factors in your decision to buy products and/or services?—‘Being green’

4. Analysis and Results

To test the proposed hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d, frequency and Chi-square test for equal proportions were used as appropriate. Table 1 summarizes Kendall Tau-b correlation results. To test H2a and H2b, an initial factor analysis was used to confirm the reduction in stated level environmental concern into a single factor, and the mean score of these four items was used as the respondent’s score for the environmental concern measure, with higher scores indicating increased level of concern and awareness about the environment. The stated environmental concern factor was then used in logistic regression, a generalized logit model with Newton–Raphson optimization technique, to test for the significance of effect of the stated environmental concern upon product preferences. Finally, in H3, logistic regression, a generalized logit model with Newton–Raphson optimization technique, was used to test for statistical significance of the relationship between initial preference for the sustainable product (vs. undifferentiated product) and subsequent preference for the innovative product (vs. undifferentiated product). For all statistical tests, an alpha value of 0.05 was utilized.

Table 1.

Kendall Tau-b correlation results.

H1a: Using frequency analysis, the hypothesis that the sustainable product will be preferred over the undifferentiated product (H1a) is supported, with a larger percentage of respondents preferring the sustainable product (86%) relative to the undifferentiated product (14%; p < 0.0001).

H1b: Using frequency analysis, the hypothesis that the product that is innovative will be preferred over the undifferentiated product (H1b) is supported, with respondents preferring the innovative product (57%) to the undifferentiated product (43%; p = 0.0070).

H1c: Frequency analysis and Chi-square test of equal proportions were used to evaluate choice between three product options: undifferentiated product (21%), sustainable product (49%), and innovative product (30%). These results do not support the hypothesis (H1c); instead, they indicate that the sustainable product is clearly preferred to either the undifferentiated or innovative products (X2(1) = 43.98, p < 0.0001).

H1d: Using frequency analysis, the hypothesis that the product that is sustainable and innovative will be preferred over the sustainable only product (H1d) is not supported, with respondents preferring the sustainable product (57%) to the combined sustainable and innovative product (43%), the opposite of what was expected (p = 0.0131).

H2a: There was no statistical significance of the model for H2a, as determined by logistic regression (Wald X2(1) = 2.25, p = 0.1339). Thus, H2a is not supported (Refer to Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for preference for H2a, H2b, and H3.

H2b: There was a statistically significant relationship between stated environmental concern and preference for the sustainable product, as evidenced by the results of the logistic regression (Wald X2(1) = 6.37, p = 0.0116), in support of H2b (Refer to Table 2).

H3: The coefficient for the preference for the sustainable (vs. undifferentiated) product variable is significant (Wald X2(1) = 17.04, p < 0.0001). The overall model is also significant (Likelihood Ratio X2(1) = 19.26, p < 0.0001). The odds ratio for the sustainable product choice coefficient is 4.084 with a 95% confidence interval (2.105, 7.924) (please refer to Table 2). This suggests that those who initially preferred the sustainable product are about four times as likely to prefer the innovative product, when offered, than those who initially preferred the undifferentiated product. Inversely, this suggests that those who prefer the undifferentiated product will still prefer the undifferentiated product under alternate product characteristic pairings. These results are consistent with the expectations in H3.

5. Discussion

Overall, the results of H1a–H1d suggest that sustainability features can be a strong differentiator, potentially stronger than innovative product features. Although contrary to some earlier findings [10,15], this corroborates the premise that sustainability is becoming a more important feature for consumers, though consumers may not fully understand the impact of their choices [21,22]. Consistent with the findings of [24], the sustainable product, framed in our study as a (CE) remanufactured product, performed better than the normal and innovative products. The argument that sustainability, properly executed, may be a key driver of competitive advantage [13,24,25] is supported by our findings as well—the sustainable option with no innovative features outperformed both the undifferentiated option and the innovative option.

Hypothesis 2a that stated concern for the environment would affect consumer product preference was not supported. There is a documented attitude–behavior gap among consumers, meaning that attitude often does not predict behavior (c.f., [52]), which in this case may present as conflicting goals for the consumer: the desire to live in a sustainable society, but reluctance to engage in activities that may require sacrifice. While we share [52]’s surprise at this non-intuitive result, we note that our findings confirm theirs, making it more likely that these findings are not a fluke and should be taken seriously moving forward.

The results of testing Hypothesis 3 suggest that variety-seeking (or -avoiding) behavior may influence consumer preference for (or against) the non-traditional product option [62], regardless of whether it is sustainable or innovative. In this case, the individual making an initial variety-seeking product decision is four times as likely to repeat their variety-seeking choice in a subsequent scenario. This finding suggests that there may be merit to considering sustainability attributes within the hedonic values spectrum and may explain the strength of preference for the sustainable product, in spite of stated environmental concern: customer preference for the sustainable product may originate in variety-seeking behavior, rather than personal and social values structures. Similar to the findings of Hypothesis 2a, this approach offers a strategy to reconcile potentially conflicting consumer goals through enhanced communication, marketing, and promotion of a variety of unique and differentiable product attributes.

This research confirms that sustainability, as a core competency, remains a strong differentiator over undifferentiated products. The failure of bundled sustainability and innovation product features to create additional attraction for consumers affirms the complex sustainability–innovation relationship, already identified in the literature, and lends support to the idea that current sustainability marketing strategy has oversimplified the role of sustainability values as the basis for consumer sustainability preferences.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study provides survey-based empirical support for [1]’s arguments, supported by stakeholder interviews, to the effect that sustainability is not necessarily a competitive advantage, but can be a competitive advantage if pursued correctly—which is also the theme of the special issue in which this article appears. It also has implications for an emerging theme both in the special issue and in the current literature in general: information deficit as a barrier to competitive sustainability. Even within a single large corporation, competitive sustainable practices do not diffuse quickly unless management actively provides the relevant information to the managers who have not yet adopted them [66]. It has been established for some time that the effects of CSR on firm success depend on the engagement strategy used [8], and it is reasonable to expect, similarly, that a sustainability strategy will affect overall success and consumer intent to buy. Corroborating this, we see that in two recent studies, researchers found that environmental labels on products did [13,26] and did not [30] affect consumer intent to purchase and financial performance. The companies that saw rewards for their labels were A-share listed firms in China, where both private citizens and the government looked favorably upon environmental labels [13] and where we might expect that the companies with the labels went to some trouble to make sure their customers were aware of the labels and understood what they meant. By contrast, the study that found that consumers pay little attention to environmental labels [30] explicitly examined the effects of providing the consumer with information about sustainability and the type of sustainable product in question before making the choice. They found that better-informed respondents are more likely to choose the sustainable option. Their conclusion is that an information campaign (perhaps similar to those used in China) would increase consumer interest in sustainable options. Providing information about the benefits of sustainable practices within a business has been shown to increase their use as well [66]. Our findings suggest that, similarly, providing information about the benefits to the consumer of a sustainable product will also increase its use. More broadly, the theoretical implication, consistent with the prior literature, is that consumers, companies, and other stakeholders do not understand the full benefit of sustainability, that this lack of understanding is a major barrier to the adoption of competitive sustainable practices (c.f., [67]), and implies that more marketing and publicity will allow these practices to be competitive. We may not need new sustainable practices so much as we need more stakeholders to understand, enact, and market practices that have already been developed.

Our study applies a marketing perspective to the resource-based theory concept of core competencies by testing how the core competencies of sustainability versus innovation influence consumers’ product preferences when the consumers are aware of the nature of the products (c.f., [13,26,30]). The results from this consumer-level approach indicate that either innovation or sustainability product differentiation constitutes a significant reason for the consumer to buy. More importantly, this research evaluates and compares innovation and sustainability against one another to determine whether, consistent with earlier, twentieth-century company-level findings [15], innovation overshadows sustainability as a differentiating factor when measured directly through expressed consumer preferences. These results are intriguing: innovation does not overshadow sustainability in the current sample of US consumers. One possible explanation for these results is that while the positive effects on financial performance of CSR overall might be overshadowed by innovation, the sustainability aspect of CSR, and potentially the remanufacturing aspect of sustainability in particular, may be a better predictor of financial performance when removed from the other elements of CSR. Another possible explanation of the findings is that sustainability may now, in the twenty-first century, constitute an innovation in itself. Though reasonable, while [15] operationalized innovation as R&D expenditures, this operationalization does not address a key point of the resource-based view: different companies compete on different bundles of resources. Companies that incorporate CSR, or some aspect such as sustainability, into their core competencies seem likely to spend R&D money on products that do incorporate CSR, or at least those aspects of it that fit their engagement strategy, such as sustainability [68]. Thus, one implication we hope to see explored in the future literature is that a specific green innovation may be more competitive in the marketplace for some companies than others, even in the same industry under the same conditions. We hope to see this theoretical implication empirically evaluated in the future.

5.2. Practical Implications

Managers, entrepreneurs, and anyone else interested in helping move the economy from a linear to a circular approach can find two practical implications in our study.

Sustainability can be a source of competitive advantage if it is bundled with the appropriate other capabilities in a strong sustainability–engagement strategy. Innovation, as operationalized here, may not be the right capability to add, but marketing and publicity in general, based on our study and the prior literature, appear likely to be a good choice. The innovation inherent in becoming able to offer a (CE) remanufactured product (c.f., [9]) may be enough innovation, even from the consumer point of view, if it is correctly and adequately marketed and publicized.

Companies with sustainable products should lobby their governments to mount an informational campaign about sustainability and its benefits for the local economy—and their specific products [13,30]. Whether or not the government is mounting an informational campaign, companies need to market their sustainability themselves. In the case of our sample, we informed all of the respondents of two key features of the sustainable option. One was that, as a remanufactured option, it was of equal or greater quality to the non-sustainable one [31,32], and the other was, of course, that it was sustainable. Thus, while sustainability may not in itself constitute a competitive advantage, it can do so if it is otherwise of equal or greater value so customers are not sacrificing their own interests if they buy it [1] and if it is bundled into an overall engagement strategy with a marketing capability that manages to get both ideas across to customers. Returning to the discussion of circular economy versus sustainability [33], we re-emphasize our earlier point that CE is arguably the most popular approach to sustainable development because of its inherent appeal to many stakeholders—in this case, with remanufacturing, to consumers.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

An unexpected conclusion to be drawn from our study is that our interpretation of the more complex resource management perspective, which involves bundling innovation with sustainability to create a stronger competitive advantage, was not supported. The more traditional approach to the resource-based view, which in this case would be that sustainability as a single resource can be the basis for competitive advantage, was supported. This finding does not invalidate the resource management perspective, nor does it invalidate conclusions such as those in [1] that sustainability, as sustainability, is not enough by itself to build a competitive advantage. Drawing on the current literature, we propose a more nuanced but, we suggest, more accurate interpretation of our findings.

In addition to contributing to the literature, this work has raised several new questions that warrant future investigation. Given the broad range of sustainable or innovative products available in the market, the operationalization of only a single product type (office furniture) produced by only a single sustainable process (remanufacturing) may limit the extent to which the newly generated insights can be applied to other contexts.

Future studies should include multiple product types and production formats, including environmentally friendly products made from scratch. This work focused on the consumer context of the United States marketplace; substantial differences in consumer response to sustainability attributes and firm conditions exist outside of the United States, i.e., in Europe, and such regional and cultural differences affecting competitive advantage should be explored. We also suggest that this research could be replicated to distinguish implications in the business-to-business context to determine the generalizability of our findings across a variety of settings and also to translate this into the consumer-to-consumer context. Given the increased global focus on environmental concerns and climate change, we suggest that additional studies should be conducted with the general consumer population to see if any changes in their preferences for sustainable products have occurred since the data were collected.

5.4. Conclusions

While the bundling of innovative and sustainable product characteristics did not increase the product’s attractiveness for the consumer, it is possible that this bundling could have a different effect in another product category (e.g., electronic devices). The finding that consumers do not appear to prefer the bundled attributes of innovation and sustainability in their products does not necessarily mean that the bundling of core competencies at the company-level would also be ineffective. Rather, that the majority of respondents indicated a preference for the remanufactured sustainable option, despite its lack of other differentiating features, suggests that remanufacturing, as a marketable feature, deserves more study. The present study also suggests that variety-seeking may provide a more accurate explanation than the stated level of environmental concern, and future research may contribute to further disentanglement of these values and preferences. Perhaps, the most important future direction would be to see if sustainable products of otherwise equal or greater value are generally successful across most industries when bundled with a marketing capability that can make customers recognize their value. We expect that sustainability will prove to be highly competitive in general—when all relevant stakeholders are well-informed.

Author Contributions

Each author made contributions to this manuscript. Conceptualization, J.D.R. and C.E.H.; method, J.D.R.; software, J.D.R.; validation, J.D.R., C.E.H. and M.K.-K.; formal analysis, J.D.R. and C.E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.R. and C.E.H.; writing—review and editing, C.E.H., J.D.R. and M.K.-K.; funding acquisition, C.E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Rochester Institute of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A decision of “exempt” was made by the Institutional Review Board of Rochester Institute of Technology (Exemption Code 46.101 (b)(2), 30 March 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kahupi, I.; Hull, C.E.; Okorie, O.; Millette, S. Building competitive advantage with sustainable products–A case study perspective of stakeholders. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanamge, C.E. Consumer Behavior in the Use and Disposal of Personal Electronics: A Case Study of University Students in Sri Lanka. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oria, L.; Crook, T.R.; Ketchen, D.K., Jr.; Sirmon, D.G.; Wright, M. The evolution of resource-based inquiry: A review and meta-analytic integration of the strategic resources–actions–performance pathway. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1383–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, S.; Lu, Y. Selling remanufactured products under one roof or two? A sustainability analysis on channel structures for new and remanufactured products. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelt, R.P. Towards a strategic theory of the firm. Compet. Strateg. Manag. 1984, 26, 556–570. [Google Scholar]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Gove, S.; Hitt, M.A. Resource management in dyadic competitive rivalry: The effects of resource bundling and deployment. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D. Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. How Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement Strategy Moderates the CSR–Financial Performance Relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1274–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velter, M.G.E.; Bitzer, V.; Bocken, N.M.P. A boundary tool for multi-stakeholder sustainable business model innovation. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 401–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. Firm performance: The interactions of corporate social performance with innovation and industry differentiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, A.; Adeleye, B.N.; Adusei, M. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Evidence from US tech firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Lee, C.-C. Impact of environmental labeling certification on firm performance: Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P. Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Du, S. Exploring the relationship between corporate social responsibility and firm innovation. Mark. Lett. 2015, 26, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.E.; Covin, J.G. Learning Exploring the interoperability of innovation, Technological Parity, and Innovation Mode Use†. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2010, 27, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J. Environmental sustainability versus profit maximization: Overcoming systemic constraints on implementing normatively preferable alternatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.-H.; Lin, C.-C.; Wang, T.-C. Exploring the interoperability of innovation capability and corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P. Consumer attitude towards sustainability of fast fashion products in the UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Langley, S.; Verghese, K.; Lockrey, S.; Ryder, M.; Francis, C.; Phan-Le, N.T.; Hill, A. The role of packaging in fighting food waste: A systematised review of consumer perceptions of packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Strenger, M.; Maier-Nöth, A.; Schmid, M. Food packaging and sustainability–Consumer perception vs. correlated scientific facts: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidou, E.; Zabaniotou, A. From Theory to Praxis: ‘Go Sustainable Living’ Survey for Exploring Individuals Consciousness Level of Decision-Making and Action-Taking in Daily Life Towards a Green Citizenship. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Lin, C.A. The effects of a sustainable vs. conventional apparel advertisement on consumer perception of CSR image and attitude toward the brand. Corp. Commun. An. Int. J. 2021, 27, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Explicating a sustainability-based view of sustainable competitive advantage. J. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 15, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machová, R.; Ambrus, R.; Zsigmond, T.; Bakó, F. The Impact of Green Marketing on Consumer Behavior in the Market of Palm Oil Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tang, J.; Wei, Z. How managerial ties impact opportunity discovery in a transition economy? Evidence from China. Manag. Decis. 2019, 58, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zeng, S.; Chen, H.; Shi, J.J. When does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis of the relationship between green innovation and financial performance. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Gallear, D.; Ghobadian, A.; Ramanathan, R. Managing knowledge in supply chains: A catalyst to triple bottom line sustainability. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, M.C.; Punzo, G. How environmental sustainability labels affect food choices: Assessing consumer preferences in southern Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 130046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, N.; Thurston, M. Remanufacturing: A key enabler to sustainable product systems. In Proceedings of the CIRP International Conference on Lifecycle Engineering, Leuven, Belguim, 31 May–2 June 2006; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, N.; Russell, J.; Bringezu, S.; Hellweg, S.; Hilton, B.; Kreiss, C.; Von Gries, N. Re-Defining Value—The Manufacturing Revolution. Remanufacturing, Refurbishment, Repair and Direct Reuse in the Circular Economy; International Resource Panel: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchin, A.; Salomone, R.; Deutz, P.; Raggi, A.; Cutaia, L. What is in a name? The rising star of the circular economy as a resource-related concept for sustainable development. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Jones, N.; Stefanakis, A. Circular economy and sustainability: The past, the present and the future directions. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Osmani, M. Integration of digital economy and circular economy: Current status and future directions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.G.; Carracedo, P.; Comas, D.G.; Siemens, C.H. An analysis of the blockchain and COVID-19 research landscape using a bibliometric study. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedjah, N.; Mourelle, L.d.; Santos, R.A.d.; Santos, L.T.B.d. Sustainable maintenance of power transformers using computational intelligence. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the business models for circular economy-towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. Environmental marketing strategy and firm performance: Effects on new product performance and market share. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahtarani, A.; Sheikhmohammady, M.; Rostami, M. The impact of social capital and social interaction on customers’ purchase intention, considering knowledge sharing in social commerce context. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabi, V.; Akbariyeh, H.; Tahmasebifard, H. A study of factors affecting on customers purchase intention. J. Multidiscip. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2015, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Oghazi, P.; Karlsson, S.; Hellström, D.; Mostaghel, R.; Sattari, S. From Mars to Venus: Alteration of trust and reputation in online shopping. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peráček, T. E-commerce and its limits in the context of the consumer protection: The case of the Slovak Republic. Jurid. Trib. Jurid. 2022, 12, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, E.; Bras, B. Making functional sales environmentally and economically beneficial through product remanufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.; Schons, L.M.; Alavi, S.; Wieseke, J. Warm glow or extra charge? The ambivalent effect of corporate social responsibility activities on customers’ perceived price fairness. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Marell, A.; Nordlund, A. Green consumer behavior: Determinants of curtailment and eco-innovation adoption. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shu, S.; Shao, J.; Booth, E.; Morrison, A.M. Innovative or not? The effects of consumer perceived value on purchase intentions for the palace museum’s cultural and creative products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manage. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. Calif. Manage. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Industry structure and competitive strategy: Keys to profitability. Financ. Anal. J. 1980, 36, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, S. Knowledge, innovation and firm performance in high-and low-technology regimes. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.R.; da Costa, M.F.; Maciel, R.G.; Aguiar, E.C.; Wanderley, L.O. Consumer antecedents towards green product purchase intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabnam, S.; Quaddus, M.; Roy, S.K.; Quazi, A. Consumer belief system and pro-environmental purchase intention: Does psychological distance intervene? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsen, C.-H.; Phang, G.; Hasan, H.; Buncha, M.R. Going Green: A Study Of Consumers’ willingness To Pay For Green Products In Kota Kinabalu. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2006, 7, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers’ perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Tarka, P.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Harnish, R.J. Consumers’ personality and compulsive buying behavior: The role of hedonistic shopping experiences and gender in mediating-moderating relationships. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.S.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Mahmood, A.; Abbas, M. Green marketing approaches and their impact on consumer behavior towards the environment—A study from the UAE. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, Q.; Tam, L.; Lee, R.P. Managing sub-branding affect transfer: The role of consideration set size and brand loyalty. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, T.B.; DelVecchio, D.; McCarthy, M.S. The asymmetric effects of extending brands to lower and higher quality. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Li, Y.-C.; Lee, M. Relationship marketing and consumer switching behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givon, M. Variety seeking through brand switching. Mark. Sci. 1984, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, K.; Berger, J.; Etkin, J.; Bollinger, B. Does time of day affect variety-seeking? J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela, A.; Hadar, L.; Morgan, S.; Maimaran, M. Variety—Seeking and perceived expertise. J. Consum. Psychol. 2019, 29, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Feng, J.; Liu, B. Pricing and service level decisions under a sharing product and consumers’ variety-seeking behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenox, M.J.; Toffel, M.W. Diffusing Environmental Management Practices within the Firm: The Role of Information Provision. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.E.; Millette, S.; Williams, E. Challenges and opportunities in building circular-economy incubators: Stakeholder perspectives in Trinidad and Tobago. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, V.L.; Crittenden, W.F.; Ferrell, L.K.; Ferrell, O.C.; Pinney, C.C. Market-oriented sustainability: A conceptual framework and propositions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).