Gastronomy Motivations as Predictors of Satisfaction at Coastal Destinations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Motivations in Gastronomy

2.2. Satisfaction in Gastronomy

3. Methodology

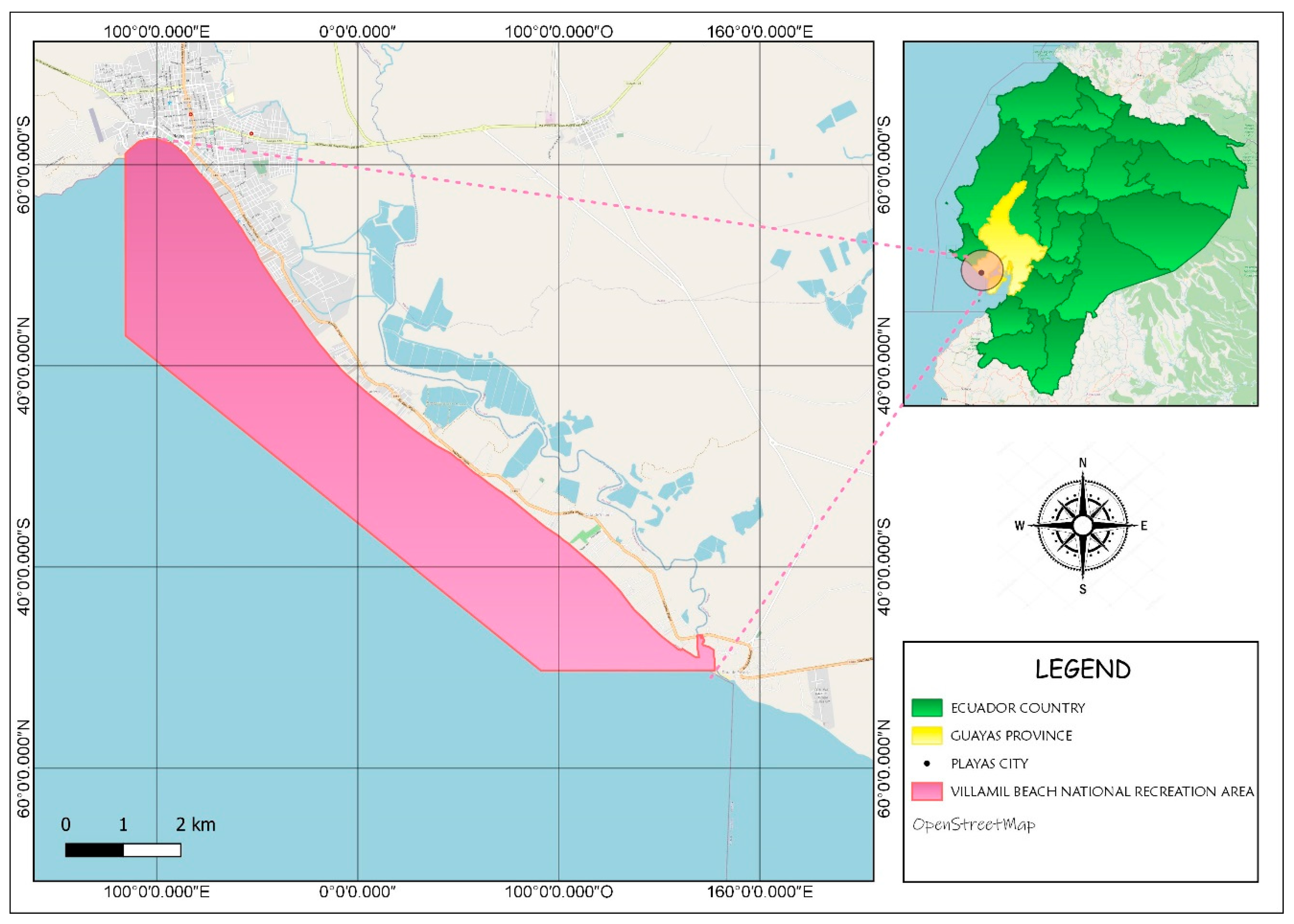

3.1. Area of Study

3.2. Survey, Data Collection, and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Aspects of the Sample

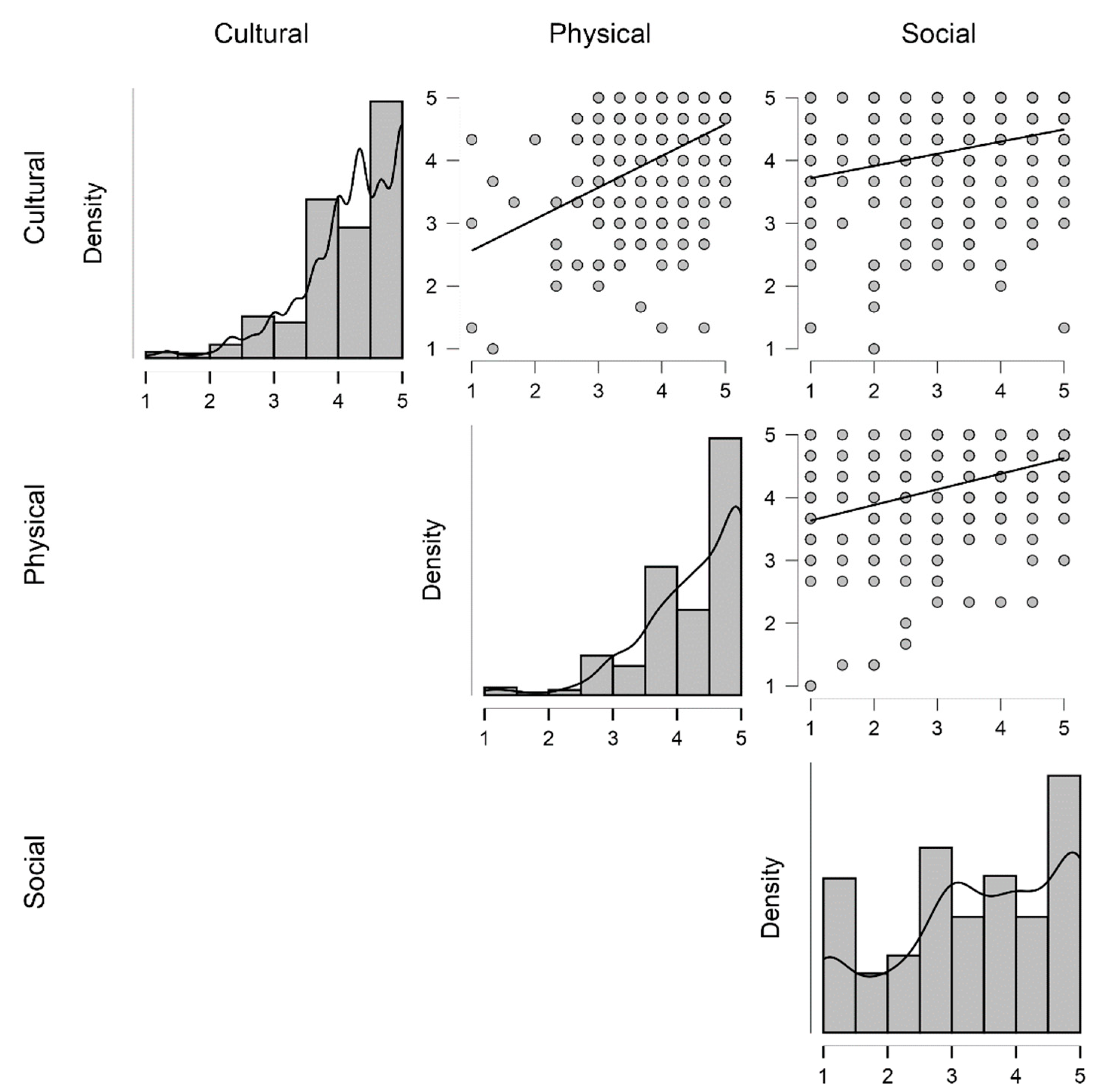

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Motivation

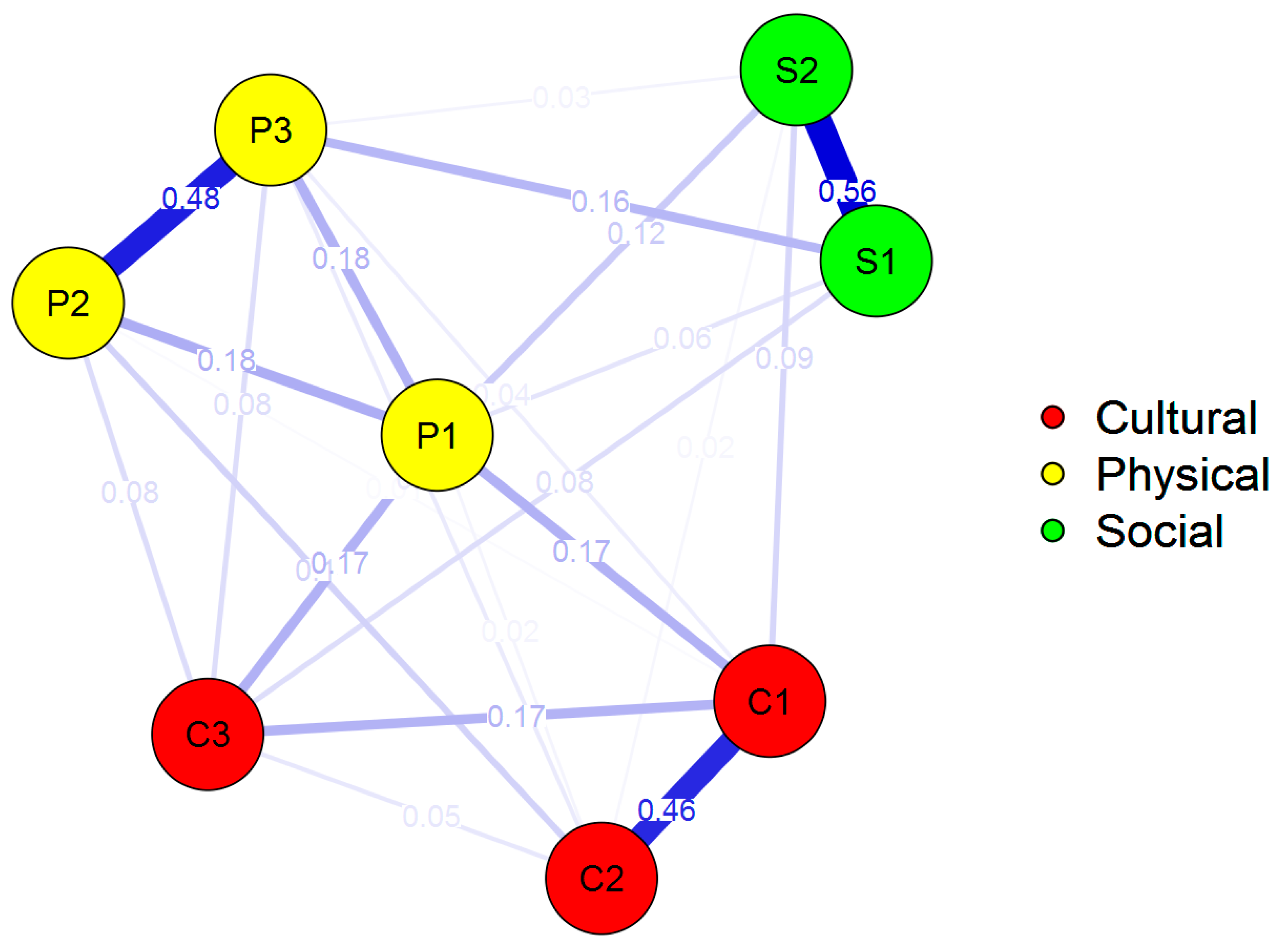

4.3. Correlation between Motivations and Satisfaction

4.4. Predictive Relationship of Motivations on Satisfaction with Gastronomy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. Food Tourism and Regional Development. Networks, Products and Trajectories; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brunori, G.; Rossi, A. Synergy and coherence through collective action: Some insights from wine routes in Tuscany. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosa, M.; Lawson, R. Revealing the lifestyles of local food consumers. Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, S.; King, B.; Nguyen, T.H.; Morrison, A. International visitor dining experiences: A conceptual framework. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2013, 20, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesser, D.; Kester, J.; Paulose, H.; Alizadeh, A.; Valentin, B. Global travel patterns: An overview. J. Travel Med. 2017, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Karim, S.; Chi, C.G.Q. Culinary tourism as a destination attraction: An empirical examination of destinations’ food image. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L.; Lee, U.I. Developing the travel career approach to tourist motivation. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E. Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Ann. Tour. Res. 1982, 9, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-L.; Backman, K.F.; Huang, Y.-C. Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 8, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudman, L.E. Tourism: A Shrinking World; Grid Inc.: Columbus, OH, USA, 1980; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-H.; Scott, N. Food tourism reviewed using the paradigm funnel approach. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manage 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.; Seyitoğlu, F. A conceptual study of gastronomical quests of tourists: Authenticity or safety and comfort? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Lamb, D. Extraordinary or ordinary? Food tourism motivations of Japanese domestic noodle tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Vieira, A.L. Destination attributes’ evaluation, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A structural modelling approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Orgaz-Agüera, F. The relevance of psychological factors in the ecotourist experience satisfaction through ecotourist site perceived value. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Razaka, A.; Shamsudinb, M.F.; Abdul, R.M. The Influence of Atmospheric Experience on Theme Park Tourist’s Satisfaction and Loyalty in Malaysia. Int. J. Inn. Creat. Chang. 2020, 6, 30–39. Available online: https://www.ijicc.net/images/Vol6Iss9/6904_Razak_2019_E_R.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Orams, M.; Lueck, M. Coastal tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Estrada-Merino, A. Motivations and segmentation of the demand for coastal cities: A study in Lima, Peru. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 23, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment. Tourists Visited the Protected Areas on the Carnival Holiday. 2019. Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/168-136-turistas-visitaron-las-areas-protegidas-en-el-feriado-de-carnaval/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. Wine and food tourism. In Special Interest Tourism: Context and Cases, Brisbane; Douglas, N., Derrett, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 307–329. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/special-interest-tourism-context-and-cases/oclc/47661075 (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Correia, A.; do Valle, P.O.; Moço, C. Modeling motivations and perceptions of Portuguese tourists. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frochot, I. A benefit segmentation of tourists in rural areas: A Scottish perspective. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramires, A.; Brandao, F.; Sousa, A.C. Motivation-based cluster analysis of international tourists visiting a World Heritage City: The case of Porto, Portugal. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kau, A.K.; Lim, P.S. Clustering of Chinese tourists to Singapore: An analysis of their motivations, values and satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 7, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.; Fraiz, J.A.; Araujo, N.; Rivo, E. Market segmentation of an inland tourist destination. The case of A Ribeira Sacra (Ourense). PASOS. J. Tour. Cult. Herit. 2016, 14, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengel, T.; Karagoz, A.; Cetin, G.; Dincer, F.I.; Ertugral, S.M.; Balık, M. Tourists’ approach to local food. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Crotts, J.C. Tourism and gastronomy: Gastronomy’s influence on how tourists experience a destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M. Exploring the Relationship between Local Food Consumption and Intentional Loyalty. Stud. Res. Tour. 2016, 30, 33–38. Available online: http://www.revistadeturism.ro/rdt/article/view/321 (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Kivela, J.J.; Crotts, J.C. Understanding travelers’ experiences of gastronomy through etymology and narration. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 161–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.S.; Tsai, C.T. Culinary tourism strategic development: An Asia-Pacific perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G.; Bilgihan, A. Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, K. Demand for the gastronomy tourism product: Motivational factors. In Tourism and Gastronomy; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, A.H.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A.; Chang, R.C. Factors influencing tourist food consumption. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Dimitrovski, D. Food markets visitors: A typology proposal. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A. Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D.; Mossberg, L.; Therkelsen, A. Food and tourism synergies: Perspectives on consumption, production and destination development. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Canalejo, A.M.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Santos-Roldán, L.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.A. Food markets: A motivation-based segmentation of tourists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Garrod, B. Experiences with local food in a mature tourist destination: The importance of consumers’ motivations. J. Gastron. Tour. 2017, 2, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Priego, M.A.; García, G.M.; de los Baños, M.; Gomez-Casero, G.; Caridad y López del Río, L. Segmentation Based on the Gastronomic Motivations of Tourists: The Case of the Costa Del Sol (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daries Ramón, N.; Cristóbal Fransi, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Mariné Roig, E. Behaviour of culinary tourists: A segmentation study of diners at top-level restaurants. Int. Ang. Cap. 2018, 14, 32–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Galati, A.; Schifani, G.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Migliore, G. Culinary tourism experiences in agri-tourism destinations and sustainable consumption—understanding Italian tourists’ Motivations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Orden-Mejía, M.; Zamora-Flores, F.; Macas-López, C. Segmentation by motivation in typical cuisine restaurants: Empirical evidence from Guayaquil, Ecuador. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 18, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Coltman, T.; Sharma, R. Do satisfied tourists really intend to come back? Three concerns with empirical studies of the link between satisfaction and behavioral intention. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howat, G.; Crilley, G. Customer service quality, satisfaction, and operational performance: A proposed model for Australian public aquatic centres. Ann. Leis. Res. 2007, 10, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žabkar, V.; Brenčič, M.M.; Dmitrović, T. Modelling perceived quality, visitor satisfaction and behavioural intentions at the destination level. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Staggs, A.; Powell, F.A. Generation Y consumers: Key restaurant attributes affecting positive and negative experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, H.; Ahn, Y. The Influence of Tourists’ Experience of Quality of Street Foods on Destination’s Image, Life Satisfaction, and Word of Mouth: The Moderating Impact of Food Neophobia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbel-Pineda, J.M.; Palacios-Florencio, B.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M.; Santos-Roldán, L. Gastronomic experience as a factor of motivation in the tourist movements. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 18, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Otoo, F.E.; Suntikul, W.; Huang, W.J. Understanding culinary tourist motivation, experience, satisfaction, and loyalty using a structural approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Levitt, J. Restaurant authenticity: Factors that influence perception, satisfaction and return intentions at regional American-style restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2017, 20, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LACAP, J.P. The Effects of Food-Related Motivation, Local Food Involvement, and Food Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: The Case of Angeles City, Philippines. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 7, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.J.; Migacz, S.; Wolf, E. Beyond the journey: The lasting impact of culinary tourism activities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piramanayagam, S.; Sud, S.; Seal, P.P. Relationship between tourists’ local food experience scape, satisfaction and behavioural intention. Anatolia 2020, 31, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, D.C.; Jokom, R.; Kristanti, M.; Wijaya, S. Tourist behavioural intentions towards gastronomy destination: Evidence from international tourists in Indonesia. Anatolia 2020, 31, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Tseng, C.H.; Lin, Y.F. Segmentation by recreation experience in island-based tourism: A case study of Taiwan’s Liuqiu Island. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Categories | N = 436 | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 210 | 48.2 |

| Female | 226 | 51.8 | |

| Age | <20 | 71 | 16.3 |

| 20–29 | 147 | 33.7 | |

| 30–39 | 109 | 25 | |

| 40–49 | 72 | 16.5 | |

| 50–59 | 27 | 6.2 | |

| 60 and above | 10 | 2.3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 216 | 49.5 |

| Free union | 51 | 11.7 | |

| Widower | 9 | 2.1 | |

| Married | 151 | 34.6 | |

| Divorced | 9 | 2.1 | |

| Level of education | Primary education | 14 | 3.2 |

| Secondary education | 159 | 36.5 | |

| University education | 225 | 51.6 | |

| Master’s/Ph.D. | 38 | 8.7 | |

| Primary occupation | Student | 114 | 26.1 |

| Private business | 33 | 7.6 | |

| Government employee | 83 | 19 | |

| Private employee | 91 | 20.9 | |

| Independent employee | 59 | 13.5 | |

| Homemaker | 24 | 5.5 | |

| Unemployed | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Retired | 7 | 1.6 | |

| Informal worker | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Other | 16 | 3.7 |

| Factor | Mean | SD | Factor Loadings | Eigenvalue | Variance (%) | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural | 3.291 | 41.13 | 7.38 | |||

| C1: To discover the flavor and quality of the local seafood | 4.22 | 0.91 | 0.831 | |||

| C2: To discover the variety of culinary offerings | 4.21 | 0.86 | 0.823 | |||

| C3:To learn about the local coastal gastronomy | 4.15 | 1.14 | 0.468 | |||

| Physical | 1.150 | 14.337 | 6.85 | |||

| P1: To consume the typical gastronomy | 4.05 | 1.16 | 0.679 | |||

| P2: To taste exotic dishes based on seafood | 4.35 | 0.95 | 0.862 | |||

| P3: To live an experience in a traditional coastal restaurant | 4.18 | 1.03 | 0.806 | |||

| Social | 0.883 | 11.043 | 7.26 | |||

| S1: I organized my trip to eat on the beach | 3.59 | 1.47 | 0.861 | |||

| S2: On the recommendation of the coastal gastronomy | 3.34 | 1.43 | 0.851 | |||

| KMO: 0.796 | ||||||

| Approx. chi-squared: 895,566 | ||||||

| Bartlett’s test: df = 28; sig < 0.000 |

| Factors | Coefficients | Sig. |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | 0.401 | p < 0.05 |

| Social | 0.308 | p < 0.05 |

| Cultural | 0.194 | p < 0.05 |

| Variables | Beta | T | Sig. | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | 0.407 | 9.963 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Social | 0.268 | 6.564 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Cultural | 0.204 | 4.997 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| (Constant) | 125.207 | 0.000 | ||

| R adjusted | 0.274 | |||

| F | 55.774 | |||

| Sig. | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvache-Franco, M.; Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carmen Lapo, M.d.; Carvache-Franco, O. Gastronomy Motivations as Predictors of Satisfaction at Coastal Destinations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811437

Carvache-Franco M, Orden-Mejía M, Carvache-Franco W, Carmen Lapo Md, Carvache-Franco O. Gastronomy Motivations as Predictors of Satisfaction at Coastal Destinations. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811437

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvache-Franco, Mauricio, Miguel Orden-Mejía, Wilmer Carvache-Franco, María del Carmen Lapo, and Orly Carvache-Franco. 2022. "Gastronomy Motivations as Predictors of Satisfaction at Coastal Destinations" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811437

APA StyleCarvache-Franco, M., Orden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Carmen Lapo, M. d., & Carvache-Franco, O. (2022). Gastronomy Motivations as Predictors of Satisfaction at Coastal Destinations. Sustainability, 14(18), 11437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811437