Abstract

The diffusion and transmission of sustainability principles may help bridge the gap between current awareness and practices and the goals of Vision 2030 and similar initiatives. Vision 2030 is a plan in progress for Saudi Arabia in alignment with the United Nations Development Program, based on building a sustainable future that will affect all sectors of society, from policy development and investment to planning and infrastructure. The objectives of these programs might be achievable if the balance of human and environmental needs is met and consumers are sufficiently aware of the ecological impacts of food production. This study aims to provide insights into food-sustainability knowledge and the threshold and motivating factors behind consumer behavioral change, specifically in the context of Vision 2030. Using convenience sampling, a cross-sectional questionnaire survey was conducted using a non-probability convenience sampling method among 398 Saudi nationals over 18 (men, 37%; women, 62%). Among other findings, the results point to a limited awareness of food sustainability or a comprehensive understanding of the negative environmental impact of food production. They suggest that it may be beneficial to consider public informational strategies to focus on the concepts of food sustainability. Finally, although there may be the intent or indication to purchase and adopt sustainable buying habits, there may be barriers to purchasing sustainable food products.

1. Introduction

In April 2016, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) unveiled its Saudi Vision 2030 [1] in alignment with the United Nations Development Program [2], a plan for economic growth based on revenue diversification away from oil and gas. The plan has three overarching objectives or themes: a vibrant society, a thriving economy, and an ambitious nation. Sustainability is important to all of these objectives. In light of the Kingdom’s limited water resources, decision makers have prioritized the strategic aim of ensuring food security as a top priority of Vision 2030.

The rapid and enormous growth in the human population and shifting global demographics have created significant environmental concerns, not least the depletion of natural resources, air pollution, and climate change. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) predicts that food production must increase by at least 60% by 2050 to meet the increased demands for food, both the need to feed the burgeoning human population and to meet the increasing demand for animal nutrition [3].

In response to these global challenges, lean manufacturing and Industry 4.0 technologies have emerged, providing new and innovative solutions to challenges of food sustainability in Saudi Arabia and throughout the world [4,5]. These techniques have been pursued by various sectors in Saudi Arabia, including by Almarai, the Kingdom’s largest dairy producer, who has led the way in taking steps in line with Vision 2030 and the use of Industry 4.0 technology [6]. Challenges arising from food systems will likely intensify in the future [7,8]. Shifting towards food systems and human diets with environmental impacts lower than the current paradigms is integral to and essential for achieving environmental sustainability [9].

For example, adopting vegan, flexitarian, and pescatarian diets can help reduce the environmental impacts of human nutritional needs, whilst also offering health benefits. Animal foods produced with reduced environmental impact—such as animal feed production with lower greenhouse gas emissions—also offer opportunities for environmental sustainability. Dietary patterns with reduced environmental impact are also linked to reduced land use and nitrogen consumption [10,11,12].

Other consumption behaviors, such as consuming local and seasonal produce, decreasing food and packaging waste, and consuming sustainably sourced fish and seafood, can also reduce the environmental impacts of the food system. According to the FAO, sustainable diets have low environmental impacts, contribute to food and nutrition security, and provide healthy lives for present and future generations [13]. Sustainable diets that are environmentally friendly support biodiversity and are culturally acceptable, accessible, financially equitable, affordable, safe, nutritionally adequate, and responsibly maximize both natural and human resources [14].

The EAT-Lancet Committee [12] recommends that multiple sectors participate and take multi-level, comprehensive measures to reduce food waste and food losses and encourage the transition to healthy diets and the global transformation towards optimized food production. The Committee also set scientific goals for sustainable food production and the provision of healthy diets. Further, the consumer awareness of choices, actions, lifestyles, and buying behaviors plays a critical role in attaining sustainable development [15]. Therefore, increasing awareness through education can be a promising means to achieving the goals of Vision 2030, an initiative that aims to change behaviors and diet toward a more sustainable future.

Previous studies in Saudi Arabia have focused on awareness and sustainability in terms of environment and energy and have touched upon, but not necessarily fully assessed, food preferences and food sustainability awareness in the Kingdom [16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

To the best of our knowledge, the study of a community’s willingness to change its current diet to one that is sustainable, as well as research conducted to assess the level of awareness of Saudis about food sustainability, is underrepresented in the literature. Therefore, this study aims to provide insights into food sustainability awareness and the threshold and motivating factors behind consumer behavioral change, specifically in the context of Vision 2030.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Study Design

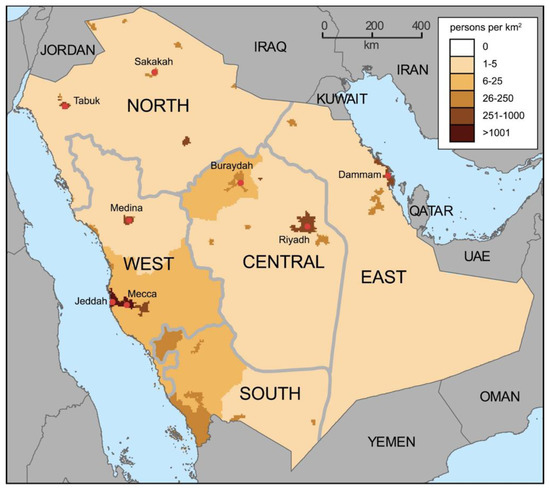

A non-probability convenience sample cross-sectional survey was conducted between 28 October and 13 November 2021. The participants (n = 398) were Saudi adults over the age of 18 (Table 1) from different strata of Saudi society (Figure 1). Participants were invited to access an online questionnaire survey (see Appendix A). The survey goals were to assess the extent to which Saudi society is aware of food sustainability, the potential effects of their purchasing behaviors based on the goals of Vision 2030, and their willingness to change their dietary and purchasing behavior. The Richard Geiger equation was used to determine the sample size. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire and share it with their contacts and on social media sites to ensure the wide distribution of the survey.

Table 1.

Percentages of the surveyed population by strata.

Figure 1.

Map showing the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia adapted from Global Rural-Urban Mapping Project (sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/gpw/), under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution License. [23]).

2.2. Questionnaire

The online web survey tool (Google Forms) was adapted from a similar study [24] and modified by the researchers before being translated into Arabic by an accredited translation office. A pilot test to check the clarity and acceptability of the questionnaire was conducted on 32 participants. Credibility and reliability were tested on four questions from the questionnaire, specifically Q7, 8, 10, and 11; the wording of sentences that showed any weakness in credibility and stability was modified. In the pilot study questionnaire, the value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76; after minor adjustments were made after pilot testing the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha increased to 0.84, indicating an improved, good level of credibility.

The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions categorized into three sections. Section One was concerned with participants’ socio-demographic background and included six questions on gender, age group, area of residence, employment, educational status, and monthly income. Section Two focused on participants’ knowledge of sustainability and food sustainability, presenting five questions about aspects related to the understanding of sustainability concepts, the environmental impact of different food groups, a healthy diet, and the use of water in food production. Section Three focuses on attitudes towards sustainable food systems based on the KSA’s Vision 2030, (Appendix A).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed and results for categories are reported using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are reported using mean standard deviation. For results given as distributions, e.g., knowledge of terms related to sustainability and the perceived impact of different food groups on sustainability, differences between groups were evaluated using a chi-square test (z-test for multiple comparisons). A two-tailed Student’s t-test and a one-way ANOVA were performed to evaluate the differences between sex and age groups, depending on whether the variables were continuous or discrete. For all statistical analyses, differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Familiarity

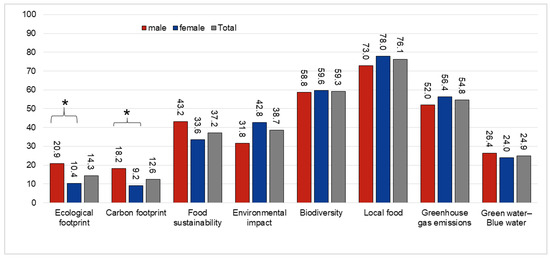

The participant familiarity with terms of sustainability ranged from a minimum of 12.6% (“carbon footprint”) to a maximum of 76.1% (“local food”) The range of percentages for all terms is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The percentages of participants familiar with terms related to food sustainability by gender. * symbol denotes statistical differences (p ≤ 0.05) between percentages by gender.

The familiarity of participants with terms by gender varied between the terms. The percentages of participants familiar with the terms “environmental impact” and “greenhouse gas emissions” were numerically higher among females, whilst the percentages familiar with the terms “ecological footprint”, “carbon footprint”, “food sustainability”, and “green water–blue water” were higher among males. The differences in the percentages between genders were statistically significant for the terms “ecological footprint” and “carbon footprint”, with the values for males being 9.5 and 9.0 percentage points higher for these two terms, respectively.

Given these results, it is possible to group the terms based on participant familiarity into “high”, “moderate”, and “low” familiarity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grouping of sustainability terms by participant familiarity.

Differences in participant familiarity with the terms used were more distinct by age group than by gender (Table 3). Originally the study was conducted using four age groups; however, the oldest age group (65–75) had a minimal sample size of only three participants. As a result, we have opted to omit this group from consideration in the results. Understanding by term and age group ranged from a minimum of 7.9% (“ecological footprint” and “carbon footprint”, age group 18–30) up to a maximum of 80.9% (“local food”, age group 50–64). The differences in the percentages by age group and term were significant for the terms “ecological footprint”, “carbon footprint”, and “food sustainability” (p ≤ 0.001), as well as “environmental impact” (p ≤ 0.01).

Table 3.

The percentages of adults familiar with terms related to food sustainability by age group.

3.2. Perception and Understanding

The understanding of a sustainable diet as perceived by participants was measured on a scale of 1-5 and ranged from a minimum of 2.6 (“few ingredients”) to a maximum of 3.72 (“rich in vegetables” and “plenty of fresh products”). Attributes can be grouped together into “high”, “moderate”, and “low” importance based on participant perceptions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Grouping of attributes that contribute to a sustainable diet based on participant perception.

The perceived attributes that define a sustainable diet varied by gender. In some cases, these differences were numerical. However, in seven out of the twelve attributes, the differences between the genders were statistically significant. For example, the importance of “plenty of fresh products” was rated 3.72 by females and 3.44 by males. In general, the importance of each item perceived by females was either numerically or statistically higher than that of males.

The results also showed that participants’ perceived importance differed between attributes and by age (Table 5). The lowest rating was in the age group 18–30 for “few ingredients” (2.34). The highest ratings were in the age group 50–64 for “rich in vegetables” (3.94). Statistically significant differences in perceptions of the importance of attributes by age group were significant for “no additives”, “low processing”, “few ingredients”, and “organic products”.

Table 5.

The perceived attributes that define a sustainable diet, on a scale of 1-5 (1 = not important at all, 5 = very important) in the surveyed population by age group.

Statements relating to the perceived importance of water use in food production varied by gender (Table 6). The minimum score of 2.39 was from females for the “Foods requiring a greater expenditure of water are of animal origin” category and the maximum score, 3.19, was also for females for the “The foods requiring a greater expenditure of water are of plant origin” category.

Table 6.

The perceived importance of water use in food production on a scale of 1–5 (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree) in the surveyed population by gender.

When participants were asked to rate the importance of water use in food production the responses varied by age (Table 7). The older population (50–64 years) reached a maximum of 3.16 for the statement “Foods requiring a greater expenditure of water are of are of plant origin”, while the younger age groups (31–49) reached a minimum at 2.35 for the same statement.

Table 7.

Scores for the perceived importance of water use in food production on a scale of 1–5 (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree) in the surveyed population by age group.

3.3. Attitude and Willingness

Scores on the importance and willingness to pay for a sustainable diet varied by gender (Table 8). The maximum score came from the male population at 3.13 when asked the question “How important is it for you that the products you consume are produced sustainably?” This question also received the highest score for all the questions in the female group. The lowest score came from the female population with a 2.28 rating for “To what extent are you willing to pay more for food and drink products that are produced sustainably?” and was also the lowest rating score in the male population.

Table 8.

Scores on the importance and willingness to pay for a sustainable diet on a scale of 1–5 (1 = not important/not willing; 5 = very important/fully willing) in the surveyed population by gender.

In terms of the importance and willingness to pay for a sustainable diet on a scale of 1–5 by age (Table 9), scores varied from a minimum of 2.53 (Age 18–30, “To what extent are you willing to pay more for food and drink products that are labeled Vision 2030 Sustainable food/drink?”) to a maximum of 5.00 (Age 50-64, “How important is it for you that the products you consume are produced sustainably?”). Scores by age were all highest for the question (“How important is it for you that the products you consume are produced sustainably?”).

Table 9.

Scores on the importance/willingness to pay for a sustainable diet on a scale of 1–5 (1 = not important/not willing; 5 = very important/fully willing) in the surveyed population by age.

By gender, the percentage of participants who considered the terms “sustainable diet” and “healthy diet” to be synonymous was 17.6% in males and 18.8% in females (Table 10). Most participants believed the terms to be “similar” (43.2% in males and 43.6% in females).

Table 10.

Percentage of participants’ opinions regarding synonymity of the terms sustainable diet and healthy diet by gender.

The percentage, by age, of participants who consider the terms “sustainable diet” and “healthy diet” to be synonymous, ranged from 14.10% in the age group 18-30 up to 22.9% in the age group 31–49 (Table 11). The highest percentage was in age group 18–30 where 49.2% of participants thought the terms were “similar.”

Table 11.

Percentage of participants’ opinions regarding synonymity of the terms sustainable diet and healthy diet by age group.

3.4. Communication Preferences

Participants strongly preferred online channels for hearing more about Vision 2030 (Table 12). The percentage of participants who expressed a preference for social media was 24.3% in males and 31.2% in females, and the percentage expressing a preference for websites was 20.9% in males and 29.6% in females. Printed materials were the least popular communication method (7.4% in males and 7.2% in females).

Table 12.

Participant preferences for hearing more about Vision 2030 by gender.

The percentage of participants who preferred social media was 35.6% in the age group 18–30, and the rate expressing a preference for websites was 33.5% in this age group (Table 13). The least popular communication method (“printed materials”) was 6.4% in the age group 50–64.

Table 13.

Participant preferences for hearing more about Vision 2030 by age group.

4. Discussion

This work provides insights into the nature of KSA peoples’ familiarity with the concepts of food sustainability. It also explores the extent of peoples’ understanding of these terms, their perceptions of the components of a sustainable food system, their motivation, and their information communication preferences. These findings are discussed here, beginning with familiarity.

Participant familiarity of with the words and phrases associated with sustainability varied considerably between the terms. There were also numerical differences in the measure of familiarity between age groups and statistically significant differences between familiarity by gender.

Participants had the greatest familiarity towards the concept of “importance of local foods”, as well as high familiarity with the concepts of “biodiversity” and “greenhouse gases” (Table 2). Moderate familiarity was shown with the terms “environmental impact” and “food sustainability.” The lowest familiarity was with the terms “green water/blue water”, “ecological footprint”, and “carbon footprint.”

Though the variation in familiarity between terms by age and by age group was high in some cases, familiarity with key concepts such as “local food” and “biodiversity” was high. Such familiarity is much higher than that found in studies carried out in Europe [25] and North America [26]. Therefore, the results for participant familiarity with the terms of sustainability are encouraging for the goals of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. Where familiarity is already high, efforts can be directed towards an increased understanding and motivation to begin the process of shifting dietary and purchasing behaviors.

The study’s results also revealed that significant differences exist in the familiarity with terms by age and by term (Table 3). Young participants (aged 18–30) showed the lowest awareness of all age groups, with awareness of terms ranging from as low as 7.9% (“ecological footprint,” “carbon footprint”) up to 75.9% (“local food”). In general terms, the awareness of terms amongst participants was higher with increasing age.

The highest awareness of terms was age group 31–49. The awareness of terms among these participants was 16.6% (“carbon footprint”) up to 74.5% (“local food”). Awareness among the age group 50–64 was generally lower than that of age group 31–49. This was the case except for the term “local food.” The awareness of the term “local food” among participants in age 50–64 was 80.9% and represented the highest term awareness within any age group.

The lowest familiarity levels were amongst the 18-30 age group, with just 7.9% of participants knowing the terms “ecological footprint” and “carbon footprint.” If the goals of Vision 2030 are to be realized, this low level of familiarity points to a need to direct information communication efforts on sustainability issues towards the 18–30 age group. Given the findings regarding participant preferences towards communication channels, this age group is best reached through online platforms, such as social media and websites. Research in North America has shown that social media can be an invaluable tool for promoting sustainability issues [27] but also that sustainability leaders are sometimes challenged by the medium and not always able to optimize social media messaging. This may be a factor worthy of further study and consideration.

As with the population’s familiarity with sustainability terms, the perception of attributes in the interviewed population that define a sustainable diet varied considerably between the attributes. There were also numerical differences in the measure of perception between age groups, as well as statistically significant differences between perception by gender. The highest perception of attributes that define a sustainable diet across all participants was “rich in vegetables” followed by “plenty of fresh products.” The study’s results suggest where and how communication efforts can be tailored in efforts to drive changes in food consumption and purchasing behavior in the KSA.

In terms of perception, results were markedly lower in men than in women, and also lower in the lower age groups. This study has shown that familiarity is higher among the young in KSA than in other populations but that understanding or perception is low. Therefore, young Saudis need to convert familiarity or knowledge into understanding and perception. Efforts to address disparities between familiarity and perception should therefore be focused on young men in particular. Unlike the findings on familiarity and younger age groups in similar studies, this finding stands in contrast to other findings. Research in Germany, for example, identified that younger people are increasingly inclined towards sustainability [28] to the point of wishing to become “anti-consumer.”

The attribute of a sustainable diet perceived to be most important to the population surveyed was “rich in vegetables.” The findings on perception are encouraging with respect to the aspirations of KSA’s Vision 2030, particularly with regards to plant-based diets. These diets typically have a much lower environmental impact than standard diets heavy in meat and dairy, not least in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and water consumption [29]. A plant-based diet also offers significant health benefits through reduced risks of heart disease [30]. A plant-based diet is the healthiest and most sustainable diet where greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced more efficiently by reducing meat and dairy consumption. Participants emphasized that the abundance of vegetables in the diet is a feature of food sustainability. Therefore, the awareness of a diet rich in vegetables may indicate a desire to reduce meat in the diet. Still, knowledge here does not necessarily translate into behavioral changes because Gulf countries are known for heavy meat consumption. In 2017, the average consumption of red meat in Saudi Arabia was 73.26 g per day [31]. The consumption of red meat in Saudi Arabia is driven by several factors, including social and cultural factors, as the offering of meat in large quantities is recognized by Arabs, especially Saudis, as a feature of generosity and hospitality for all occasions. Therefore, it may be difficult for Arabic societies to decrease meat consumption and switch to a plant-based diet, so reducing consumption may be the best option. This is one of the biggest challenges we face to achieve Vision 2030. An awareness of the importance of a diet “rich in vegetables” is already in place within the KSA, which acts as a foundation to begin incentivizing changes in consumption and purchasing behaviors. This means that an opportunity exists to drive changes to dietary and purchasing behaviors among Saudis.

To date, the awareness of the importance of vegetable consumption to the sustainability of food systems has not necessarily translated into behavioral changes. Gulf countries, such as Saudi Arabia, are known for heavy meat consumption [32], with the consumption of red meat driven by several factors, including social and cultural factors [33]. The offering of meat in large quantities is recognized by Arabs, especially Saudis, as a feature of generosity and hospitality for all occasions. In 2017, the average consumption of red meat in Saudi Arabia was over 73 g per day [31]. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity for achieving Vision 2030. The production of animal meat for human consumption utilizes a great deal of water. For example, 1 kg of beef requires 4000–24,000 L of water, while 1 kg of chicken requires 3000–6000 L [34]. The water consumption of sheep and goat vary considerably, but a generally accepted figure is 6000 L per kg. Therefore, animal products have a significant water footprint compared to crops and are responsible for about 29% of water pollution [35].

In terms of perceptions about processed foods and fizzy drinks, there are also already high levels of awareness (Figure 3 and Figure 4). There is, therefore, little need for developing strategies designed to generate awareness or build perception around these elements and their role in sustainability. This work suggests that the general population of the KSA is ready to be incentivized towards reducing their consumption of these products. Such motivations can perhaps be engendered either through monetary terms (higher prices) or through warnings about the associated health risks of their consumption.

Figure 3.

The perceived impact on the sustainability of the different food groups in the surveyed population by gender. p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 4.

The perceived impact on the sustainability of the different food groups in the surveyed population by age group. (18–30 years, n = 191; 31–49 years, n = 157; 50–64 years, n = 47), ** p ≤ 0.01.

However, this work has shown that generating awareness is still necessary in the KSA. For example, fewer than 20% of the participants (19.8%) recognized the meat industry as damaging to the environment (Figure 3). Likewise, fewer than 20% of the participants (9.5%) perceived the milk and dairy industries as damaging the environment. There is, therefore, a need for generating awareness around these factors affecting sustainability. Concerning meat, this need for awareness-raising and perception-building is more critical for the 18–50 age group, while for milk and dairy it is essential for the 51–67 age group. Therefore, informational campaigns targeting age group and food system attributes might be helpful.

Motivation to pay higher prices for sustainably produced food and drink was higher in men and higher in more mature age groups. Finding ways to ensure sustainably produced food and drink is more competitively priced and accessible to the most significant portion of the population may help make sustainable dietary and purchasing goals more realizable.

The questions on communication preferences indicated a general preference towards online channels, such as social media and websites, regardless of gender or age. However, there was interest was in communication through a health practitioner and/or formal education programs. These categories were notably higher for the age group 18–30 and also for females. The results suggest that the desire to learn more is stronger in young Saudi women. The ambition to achieve the KSA Vision 2030 could be aspired towards by providing services and formal education to younger people, particularly women. The role of age and gender is often present in debates on sustainability. Other researchers in other parts of the world have also found that gender is a crucial feature of driving change towards sustainability [36] and that integrating female perspectives into decisions can help to push a sustainability agenda forward [37]. As well as directing attention towards the young, efforts to drive dietary changes in the KSA as a part of Vision 2030 may also be most effective by engaging women.

It is common for there to be misconceptions about the terms and topics of sustainability, regardless of the population under study [37]. It has been suggested that the most effective means of addressing misconceptions on sustainability is through concrete initiatives and also by citing specific case studies to facilitate understanding [38]. The KSA Vision 2030 is one such initiative capable of meeting this objective. This work has sought to show potential pathways to optimizing food sustainability awareness and dietary and purchasing behavioral change.

Given the more promising and positive results, an overall lack of awareness about the nexus between food consumption and purchasing behaviors and environmental consequences is still a barrier to achieving the goals of Vision 2030 and is considered a stakeholder challenges. Awareness must be elevated around the need for change so that the planet and the resources necessary for human survival continue to be available both now and in the future. This awareness-raising is needed to enable an augmented understanding of the interrelated issues of food, diet, and environmental sustainability and to incentivize the motivation to change behavior.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Saudi Arabia which aims to assess awareness and knowledge of food sustainability and assess consumers’ sustainable purchasing behavior based on the objectives of the Saudi Vision 2030. However, the present study has its limitations. Due to COVID-19 restrictions and limited access to a national database of potential participants, we used a non-representative cross-sectional design, which makes the results non-generalizable. Additionally, in terms of limitations, there is the potential for self-reported bias with an online questionnaire.

5. Conclusions

The results concluded that while the sample was familiar with the terms used when speaking about sustainability in general, that there is a low level of understanding about food sustainability and of the negative environmental impacts of food production in particular. The general case is that people link sustainability characteristics to manufacturing and production processes but not necessarily to dietary behaviors. Ultimately, the results concluded that there is a low awareness of food sustainability and little understanding of the negative impact of food production on the environment. However, the study found that there is consumer willingness and interest in buying sustainable food products or sustainable products that bear the label of Vision 2030. This finding suggests that it might be beneficial for local, educational, and national strategies to focus on and specifically motivate younger generations towards a more sustainable lifestyle both now and in the future. Removing barriers to affordable, local, and sustainable food—such as high prices, limited availability, and a lack of food sustainability awareness and education—may be a good step forward.

The realities of climate change have become more urgent and ubiquitous, resulting in new programs and initiatives to meet modern challenges, such as the KSA’s “Vision 2030”. Programs such as these should be sustainability-focused partnerships and dialogues between public health practitioners, researchers, and the public, to continue to strengthen and help guide humanity towards the best possible personal, public, and environmental outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and N.M.; methodology, A.A. and N.M.; validation, N.M.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, A.A. and N.M.; resources, N.M.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; visualization, A.A. and N.M.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A. and N.M.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee at King Saud University (KSU-HE-21-627).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed online consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by a grant from the “Research Center of the Female Scientific and Medical Colleges”, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- Questionnaire

- Food Sustainability Knowledge Among Saudis: Towards the Goals of Saudi Vision 2030

- You are about to participate with us in a study entitled Knowledge of Food Sustainability among Saudis, which aims to know the extent of awareness of food sustainability and purchasing behavior among Saudis in the context of the sustainability goals in Saudi Vision 2030.

- If you are a Saudi and your age is 18 years or more, we invite you to participate in filling out the questionnaire, which will not take more than about 10 min, noting that the study is approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee at King Saud University (Reference No. E-21-627) and we inform you that All information provided will be treated confidentially and used for research purposes only.

- Sociodemographic Data

- Q.1.

- Gender

- Male

- Female

- Q.2.

- How old are you?

- 18–30 years

- 49–31 years

- 64–50 years

- 74–65 years

- 75 < years

- Q.3.

- Where do you live?

- Central

- South

- North

- East

- West

- I live abroad

- Q.4.

- Employment Status: Are you currently employed?

- Yes

- No

- Q.5.

- What is your highest level of education?

- Primary

- Intermediate

- Secondary

- Diploma

- University

- Postgraduate

- Q.6.

- Household income?

- Less than 2000 SAR

- From 2000 to 5000 SAR

- From 5000 to 7000 SAR

- From 7000 to 10,000 SAR

- More than 10,000 SAR

- Knowledge of Sustainability and Food Sustainability

- Q.7.

- Do you know the following concepts?

Table A1.

Questionnaire table on familiarity of concepts.

Table A1.

Questionnaire table on familiarity of concepts.

| Concepts | Yes | No | Heard of the Term but Don’t Know What It Means |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological footprint | |||

| Carbon footprint | |||

| Food sustainability | |||

| Environmental impact | |||

| Biodiversity | |||

| Local food | |||

| Greenhouse gas emissions | |||

| Green water–blue water |

- Q.8.

- From 1 to 5, to what extent do you consider that each of the following aspects contributes to a sustainable diet? Being, 1: “Not important at all” and 5: “Very important”.

Table A2.

Questionnaire table on what contributes to a sustainable diet.

Table A2.

Questionnaire table on what contributes to a sustainable diet.

| Not | Little | Important | Very | DK/DA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low environmental impact | |||||

| Respectful of biodiversity | |||||

| No additives | |||||

| Low processing | |||||

| Few ingredients | |||||

| Organic growth/ecologic products | |||||

| Plenty of fresh products | |||||

| Rich in vegetables | |||||

| Typical from own culture/culturally sensitive | |||||

| Locally produced | |||||

| Affordable | |||||

| Easy to follow |

- Q.9.

- Do you believe that the terms “sustainable diet” and “healthy diet” are synonymous?

- Yes

- Are similar concepts, but not the same

- No

- DK/DA

- Q.10.

- Please give your opinion on the contribution of the following foods to the sustainability of the planet (less damage):

Table A3.

Questionnaire table on contribution of food types to sustainability.

Table A3.

Questionnaire table on contribution of food types to sustainability.

| Positive Impact | Negative Impact | I Don’t Know (DK/DA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | |||

| Meats and derivatives | |||

| Fish, shellfish, and derivatives | |||

| Milk and Dairy | |||

| Eggs | |||

| Processed foods | |||

| Sodas and processed drinks |

- Q.11.

- From 1 to 5, indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements related to water and its use in food production.

- Being, 1: “Do not agree” and 5: “Completely agree”.

Table A4.

Questionnaire table on importance of concepts.

Table A4.

Questionnaire table on importance of concepts.

| Do Not Agree | Agree a Little | Mostly Agree | Agree | Completely Agree | DK/DA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enough water for the planet is granted by the natural cycle of water | ||||||

| The foods requiring a greater expenditure of water are of animal origin | ||||||

| The foods requiring a greater expenditure of water are of vegetable origin |

- Attitudes to Sustainable Diets

- Q.12.

- From 1 to 5: How important is it for you that the products you consume are produced in a sustainable way? Being, 1: “Not important at all” and 5: “Very important”.

- Not Important at All

- Of Little Importance

- Moderately Important

- Important

- Very Important

- DK/DA

- Q.13.

- From 1 to 5: To what extent are you willing to pay more for food and drink products that are produced in a sustainable way? Being, 1: “Not at all” and 5: “Willing”.

- Not at All

- Unwilling

- Moderately Willing

- Quite Willing

- Willing

- DK/DA

- Q.14.

- From 1 to 5: To what extent are you willing to pay more for food and drink products that are labeled Vision 2030 Sustainable food/drink? Being, 1: “Not at all” and 5: “Willing”.

- Not at All

- Unwilling

- Moderately Willing

- Quite Willing

- Willing

- DK/DA

- Q.15.

- Where would you go to learn more about Vision 2030 sustainable foods?

- social media

- radio/television

- health practitioner

- website

- printed materials

- formal education programs (Schools and universities)

- I would not seek out this information

- others

References

- Saudi Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Alexandratos, N.; Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision; (ESA working paper no. 12-03, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A.; Aït-Kaddour, A.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M.; Rathod, N.B.; Bader, F.; Barba, F.J.; Biancolillo, A.; Cropotova, J.; Galanakis, C.M.; Jambrak, A.R.; et al. The Fourth Industrial Revolution in the Food Industry—Part I: Industry 4.0 Technologies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, D.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Singh, Y.; Jagtap, S. Optimising Changeover through Lean-Manufacturing Principles: A Case Study in a Food Factory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osland, A. Saudi Arabia: Almarai and Vision 2030; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlYami, M.; Watson, R. An Overview of Nursing in Saudi Arabia. J. Health Spec. 2014, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable Food Consumption: An Overview of Contemporary Issues and Policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Sustainable Food Systems Concept and Framework; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, B.C.; van der Voort, J.R.; Grofelnik, K.; Eliasdottir, H.G.; Klöss, I.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. Which Diet Has the Least Environmental Impact on Our Planet? A Systematic Review of Vegan, Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmul, S.; Dangour, A.D.; Green, R.; Liew, Z.; Haines, A.; Scheelbeek, P.F.D. Climate Change Mitigation through Dietary Change: A Systematic Review of Empirical and Modelling Studies on the Environmental Footprints and Health Effects of ‘Sustainable Diets’. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 123014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Sustainable Healthy Diets Guiding Principles; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H. Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity Directions and Solutions for Policy, Research and Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hanss, D.; Böhm, G. Sustainability Seen from the Perspective of Consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 36, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.; Al-Shihri, F.; Ahmed, S. Students’ Assessment of Campus Sustainability at the University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.K.H.; El-Hassan, W.S. Interdisciplinary Inquiry-Based Teaching and Learning of Sustainability in Saudi Arabia. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2020, 22, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhefnawy, M. Sustainability Issues Awareness: A Case Study in Dammam University. J. Archit. Plan. 2014, 26, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhayyal, B.; Labib, W.; Alsulaiman, T.; Abdelhadi, A. Analyzing Sustainability Awareness among Higher Education Faculty Members: A Case Study in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaati, T.; El-Nakla, S.; El-Nakla, D. Level of Sustainability Awareness among University Students in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KHAN, U.; HAQUE, M.I.; KHAN, A.M. Environmental Sustainability Awareness in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.; Adenle, Y.; Saghir, B. Sustainability Assessment of Higher Education Institutions in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubrani, Y.M.; Wetton, J.H.; Jobling, M.A. Extensive Geographical and Social Structure in the Paternal Lineages of Saudi Arabia Revealed by Analysis of 27 Y-STRs. Forensic. Sci. Int. Genet. 2018, 33, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, Á.; Achón, M.; Krug, A.C.; Varela-Moreiras, G.; Alonso-Aperte, E. Food Sustainability Knowledge and Attitudes in the Spanish Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J.; Halicka, E.; Laskowski, W. Do Europeans Consider Sustainability When Making Food Choices? A Survey of Polish City-Dwellers. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1330–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabian-Riasati, S. Food Sustainability Knowledge and Its Relationship with Dietary Habits of College Students. Austin J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 5, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.; Takahashi, B.; Cunningham, C.; Lertpratchya, A.P. The Roles of Social Media in Promoting Sustainability in Higher Education. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 4863–4881. [Google Scholar]

- Ziesemer, F.; Hüttel, A.; Balderjahn, I. Young People as Drivers or Inhibitors of the Sustainability Movement: The Case of Anti-Consumption. J. Consum. Policy 2021, 44, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmie, R.J. Impact of Dietary Meat and Animal Products on {GHG} Footprints: The {UK} and the {US}. Climate 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, T.J.; Davey, G.K.; Appleby, P.N. Health Benefits of a Vegetarian Diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1999, 58, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinawy, A.; Abdelradi, H.; Said, R. Determinants of Fresh and Processed Meat Consumption in Saudi Arabia. Sci. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 3, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigatu, G.; Motamed, M. Middle East and North Africa Region: An Important Driver of World Agricultural Trade; United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Musaiger, A.O. Socio-Cultural and Economic Factors Affecting Food Consumption Patterns in the Arab Countries. J. R. Soc. Health 1993, 113, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbens-Leenes, P.W.; Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The Water Footprint of Poultry, Pork and Beef: A Comparative Study in Different Countries and Production Systems. Water Resour. Ind. 2013, 1–2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. A Global Assessment of the Water Footprint of Farm Animal Products. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C. Are Women the Key to Sustainable Development? Sustain. Dev. insights, Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future, Boston University: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.bu.edu/pardee/files/2010/04/UNsdkp003fsingle.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Oedl-Wieser, T. Women as Drivers for a Sustainable and Social Inclusive Development in Mountain Regions –The Case of the Austrian Alps. Eur. Countrys. 2017, 9, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Filho, W.L. Dealing with Misconceptions on the Concept of Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2000, 1, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).