Revisiting the Concept of Values Taught in Education through Carroll’s Corporate Social Responsibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Values Education

3. The Concept of Values

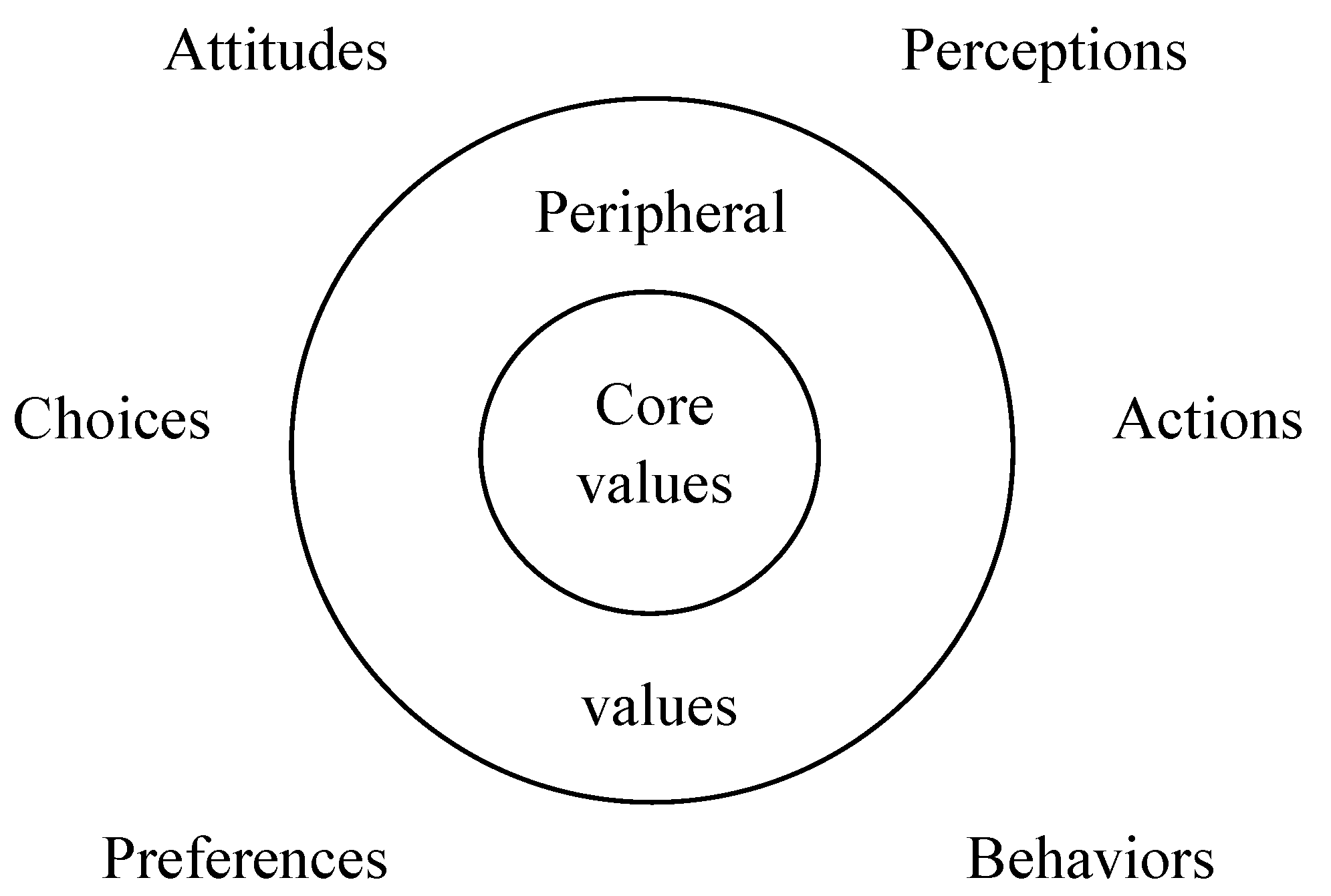

4. The Two-Layer Paradigm

4.1. Underlying Assumptions of the Paradigm

4.2. The Circular Paradigm

4.3. The Nature of Human Values

4.4. An Example Showing the Difficulties in Teaching Values

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, W.D. Infusing moral education into English language teaching: An ontogenetic analysis of social values in EFL textbooks in Hong Kong. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2019, 40, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey, A.G.; Pickering, N. Putting it on the table: Toward better cultivating medical student values. Med. Sci. Educ. 2018, 28, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Dictionary; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Sagiv, L.; Roccas, S.; Cieciuch, J.; Schwartz, S.H. Personal values in human life. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagatovsky, V.N. Human qualities and the system of basic values. J. Value Inq. 1996, 30, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliotti, E. Democracy’s value: A conceptual map. J. Value Inq. 2020, 54, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G.L.; McKinnon, J.L. Cross-cultural research in management control systems design: A review of the current state. Account. Organ. Soc. 1999, 24, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolicz, J. Core values and cultural identity. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1981, 4, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, A.; Goodwin, R. The dual route to value change: Individual processes and cultural moderators. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2011, 42, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M.; Harpaz, I. Core and peripheral values: An over time analysis of work values in Israel. J. Hum. Values 2009, 15, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F.A. Organizational identity and strategy as a context for the individual. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 1996, 13, 19–64. [Google Scholar]

- Musschenga, A.W. Education for moral integrity. J. Philos. Educ. 2001, 35, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perry, M.J. The Political Morality of Liberal Democracy; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Hockerts, K. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability in Scandinavia: An overview. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; Gálvez-Sánchez, F.J.; López-Martínez, G.; Molina-Moreno, V. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability. A bibliometric analysis of their interrelations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up? Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B.; Brown, J.A. Corporate Social Responsibility: A review of current concepts, research and issues. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Weber, J., Wasieleski, D., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brondani, M.A. Teaching social responsibility through community service-learning in predoctoral dental education. J. Dent. Educ. 2012, 76, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Morse, S.; Ma, Q. Corporate social responsibility and sustainable development in China: Current status and future perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, J.; Carnero, M.C. Assessment of social responsibility in education in secondary schools. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Menezes, I. University social responsibility, service learning, and students’ personal, professional, and civic education. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 617300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLure, M. “Clarity bordering on stupidity”: Where’s the quality in systematic review? J. Educ. Policy 2005, 20, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrop, M. Can values be taught? The myth of value-free education. Trames 2015, 19, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algraini, S. Education for human development: A capability perspective in Saudi public education. Compare 2019, 51, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighouse, H. On Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B. The Aims of Education. In On Education: Especially in Early Childhood; Russell, B., Ed.; Unwin Books: London, UK, 1973; pp. 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Dictionary; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/personality (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Komarraju, M.; Karau, S.J.; Schmeck, R.R.; Avdic, A. The big five personality traits, learning styles, and academic achievement. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, H. Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: A look at five meta-analyses. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirhosseini, M.H.; Kazemian, H. Machine learning approach to personality type prediction based on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Choi, H.-J.; Hyun, S.S. MBTI personality types of Korean cabin crew in Middle Eastern airlines, and their associations with cross-cultural adjustment competency, occupational competency, coping competency, mental health, and turnover intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadipour, S. Personality types and intercultural competence of foreign language learners in education context. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 236. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, R.; Swan, A.B. Evaluating the validity of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator theory: A teaching tool and window into intuitive psychology. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 2019, 13, e12434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. The role of idealism and relativism as dispositional characteristics in the socially responsible decision-making process. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 56, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazak, R. Ethnic envy: How teens construct whiteness in globalized America. In Globalizing the Streets: Cross-Cultural Perspectivs on Youth, Social Control, and Empowerment; Salek, F., Brotherton, D.C., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, D.R. Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, E.H.; Stanciu, A.; Boehnke, K. A new empirical approach to intercultural comparisons of value preferences based on Schwartz’s theory. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernilo, D.A. Social Theory of the Nation-State: The Political Forms of Modernity beyond Methodological Nationalism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Essays on Self-Reference; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, J.T.; Basevich, E.; Dickson, E.S.; Noorbaloochi, S. The place of values in a world of politics: Personality, motivation, and ideology. In Handbook of Value: Perspectives from Economics, Neuroscience, Philosophy, Psychology, and Sociology; Brosch, T., Sander, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 351–374. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N.A.; Shaw, S.; Ross, H.; Witt, K.; Pinner, B. The study of human values in understanding and managing social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.C. The concept of value in resource allocation. Land Econ. 1984, 60, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, E.; Curtis, A.; Pannell, D.; Allan, C.; Roberts, A. Understanding the role of assigned values in natural resource management. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 17, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baard, P. The goodness of means: Instrumental and relational values, causation, and environmental policies. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, G. Values in education (1). In New Essays in the Philosophy of Education; Langford, G., O’Connor, D.J., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2010; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, D. Can instrumental value be intrinsic? Pac. Philos. Q. 2012, 93, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennick, D.; Kiel, F. Moral Intelligence: Enhancing Business Performance and Leadership Success; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clarken, R.H. Moral Intelligence in the Schools. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Michigan Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA, 20 March 2009; Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED508485.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. The refined theory of basic values. In Values and Behavior; Roccas, S.S., Sagiv, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L. Personal values and behavior: Taking the cultural context into account. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberman, M.; Post, L. Teachers for multicultural schools: The power of selection. Theory Pract. 1998, 37, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.T. There is no such thing as ideal theory. Soc. Philos. Policy 2016, 33, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanski, A. Why obey the law? Plato’s answer. Akroterion 1999, 44, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, M. A Natural History of Human Morality; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Little, J.M.; Gaier, S.; Spoutz, D. The role of values, beliefs, and culture in student retention and success. In Critical Assessment and Strategies for Increased Student Retention; Black, R.C., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Vignoles, V.L.; Smith, P.B.; Becker, M.; Easterbrook, M.J. In search of a pan-European culture: European values, beliefs, and models of selfhood in global perspective. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 868–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magun, V.; Rudnev, M.; Schmidt, P. Within- and between-country value diversity in Europe: A typological approach. Eur. Soc. Rev. 2016, 32, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjoon, S. Corporate governance: An ethical perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, H.L.; Vredenburg, H. Morals or economics? Institutional investor preferences for corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osagie, E.R.; Wesselink, R.; Runbaar, P.; Mulder, M. Unraveling the competence development of corporate social responsibility leaders: The importance of peer learning, learning goal orientation, and learning climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Ethical challenges for business in the new millennium: Corporate social responsibility and models of management morality. Bus. Ethics Q. 2000, 10, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, K.G.; Gioia, D.A. Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I. Lack of theory building and testing impedes progress in the factor and network literature. Psychol. Inq. 2020, 31, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, S. Theory building is neither an art nor a science: It is a craft. J. Inf. Technol. 2021, 36, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, K.; Vassileva, J. Gender difference and difference in behavior modeling in fitness applications: A mixed-method approach. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmohammadi, M.J.; Baker, C.R. Accountants’ value preferences and moral reasoning. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termes, R. Ethics in financial institutions. In The Ethical Dimension of Financial Institutions and Markets; Argandoña, A., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Art, R.J. A Grand Strategy for America; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.M.; Steele, C.A. Assisting democrats or resisting dictators? The nature and impact of democracy support by the United States National Endowment for Democracy, 1990–1999. Democratization 2005, 12, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Kendal, D. The role of social values in the management of ecological systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Freire, E.; Marques, B.G.; de Jesus Miranda, M.L. Teaching values in physical education classes: The perception of Brazilian teachers. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Holanda, C.; Lins, G.; Hanel, P.H.P.; Johansen, M.K.; Maio, G.R. Mapping the structure of human values through conceptual representations. Eur. J. Personal. 2019, 33, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, L.G.; Tyahur, P.M.; Jackson, J.A. Civility and academic freedom: Extending the conversation. J. Contemp. Rhetor. 2016, 6, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lennick, D.; Kiel, F. Moral leadership: Caring for and believing in people. Manag. Today 2005, 21, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dancák, P. The human person dignity and compassion. Philos. Canon Law 2017, 3, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, M.W. What works in values education. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 50, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, J.M. Values and values education in schools. In Values in Education and Education in Values; Halstead, J.M., Taylor, M.J., Eds.; The Falmer Press: London, UK, 1996; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, K.M. Teaching values: Ethical and emotional attunement through an educational humanities approach. Educ. Dev. 2020, 21, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Morlino, L. “Good” and “bad” democracies: How to conduct research into the quality of democracy. J. Communist Stud. Transit. Politics 2004, 20, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.T. Ideology in the schools: Developing the teacher’s civic education ideology scale within the United States. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2019, 14, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, K.A.; Adair, J.K.; Colegrove, K.S.S.; Lee, S.; Falkner, A.; McManus, M.; Sachdeva, S. Reconceptualizing civic education for young children: Recognizing embodied civic action. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2020, 15, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinenko, S.; Tutuska, J.; Matthews, L. Bridging civic engagement to civic responsibility through short-term, international service-learning experiences: A qualitative analysis of student reflections. eJournal Public Aff. 2018, 7, 108–131. [Google Scholar]

- Muddiman, E. Degree subject and orientations to civic responsibility: A comparative study of business and sociology students. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2020, 61, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, X.; Haste, H.; Selman, R.L.; Luan, Z. Compliant, cynical, or critical: Chinese youth’s explanations of social problems and individual civic responsibility. Youth Soc. 2017, 49, 1123–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.H.; Jaeger, A.J. A new context for understanding civic responsibility: Relating culture to action at a research university. Res. High. Educ. 2007, 48, 993–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronconi, L. From Citizen’s Rights to Civic Responsibilities; IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12457; Institute of Labor Economics (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3427594 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- United Nations. What Is the Rule of Law; United Nations Publications Customer Service: Herndon, VA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/what-is-the-rule-of-law (accessed on 27 January 2020).

- Guagnano, G.; Santini, I. Active citizenship in Europe: The role of social capital. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A. Obligation to obey the law: A study of the death of Socrates. South. Calif. Law Rev. 1976, 49, 1079–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Colby, A.; Ehrlich, T. Educating Citizens: Preparing America’s Undergraduates for Lives of Moral and Civic Responsibility; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Janoski, T. Citizenship and Civil Society: A Framework of Rights and Obligations in Liberal, Traditional, and Social Democratic Regimes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rostbøll, C.F. Kant, freedom as independence, and democracy. J. Politics 2016, 78, 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L. Human rights as an ideology? Obstacles and benefits. Crit. Sociol. 2020, 46, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, D.A.; Sales, B.D. Legal standards, expertise, and experts in the resolution of contested child custody cases. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2000, 6, 843–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, D.P.; Swan, A.B.; Rutchick, A.M. Ideological belief bias with political syllogisms. Think. Reason. 2019, 26, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauginienė, L.; Urbanovič, J. Social responsibility in transition of stakeholders: From the school to the university. Stakehold. Gov. Responsib. 2018, 14, 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sassower, R. Postmodern relativism as enlightened pluralism. In Relativism and Post-Truth in Contemporary Society; Stenmark, M., Fuller, S., Zackariasson, U., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, E.W.L. Revisiting the Concept of Values Taught in Education through Carroll’s Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811280

Cheng EWL. Revisiting the Concept of Values Taught in Education through Carroll’s Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811280

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Eddie W. L. 2022. "Revisiting the Concept of Values Taught in Education through Carroll’s Corporate Social Responsibility" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811280

APA StyleCheng, E. W. L. (2022). Revisiting the Concept of Values Taught in Education through Carroll’s Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability, 14(18), 11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811280