Can Tanker Water Services Contribute to Sustainable Access to Water? A Systematic Review of Case Studies in Urban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Individual case studies are often highly localized and the sustainability impacts of TWM strongly depend on the overall water provision system in place as well as the institutional landscape it is embedded in.

- The frequently informal nature of TWM impedes the creation of a sound and comparable empirical basis because of the inherent interest of actors in shadow economy markets to conceal their activities [24].

- Diverging concepts are used to support normative assessments of sustainability impacts. It is not always clear which benchmarks TWM are compared against and whether the criticism is based on a relevant alternative or an idealized supply situation.

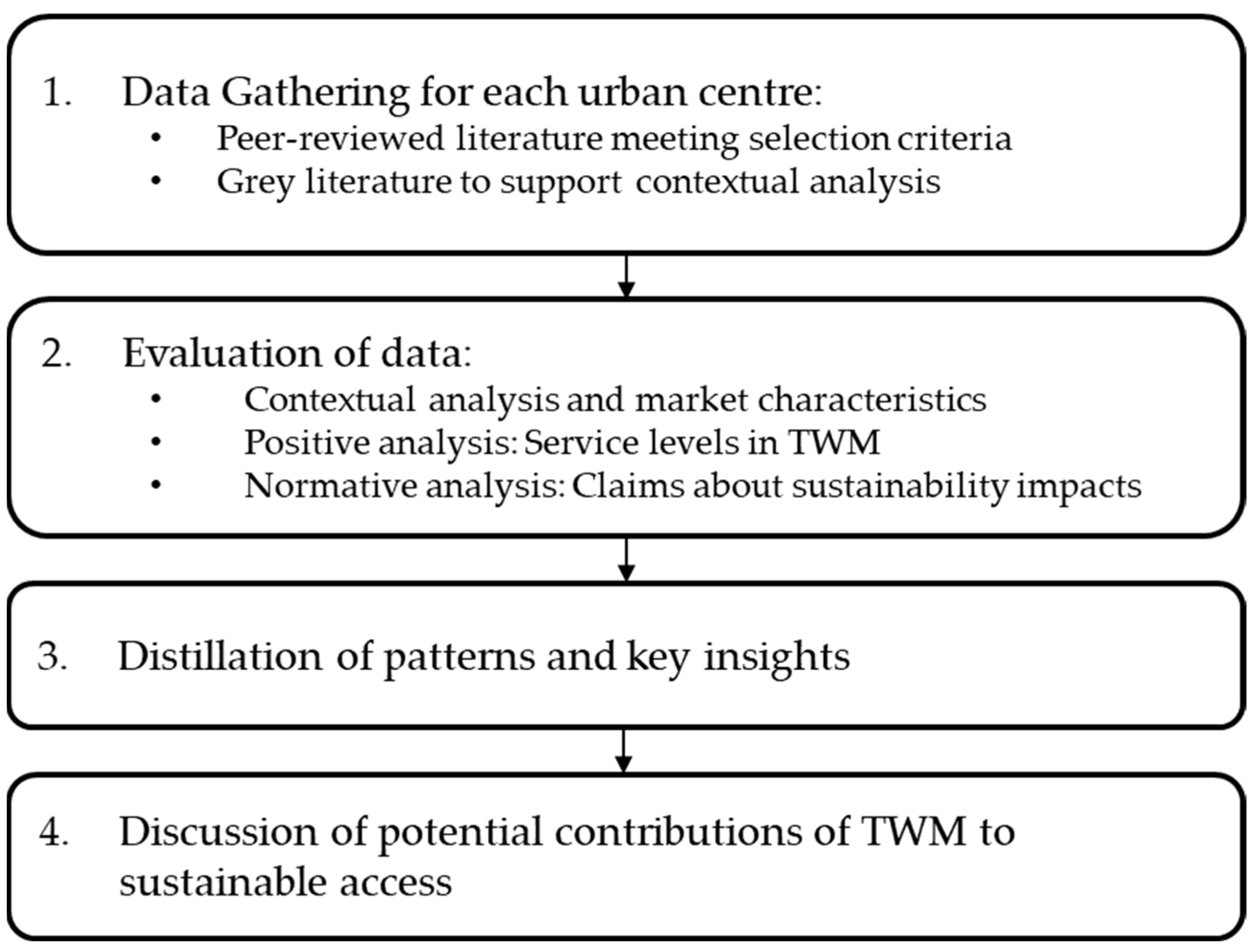

- Positive analysis: Access to water is a key objective of water policy, expressed in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 [28] and the human right to water [29]. Access is usually understood as gradual, i.e., non-binary, and is shaped by the non-pecuniary dimensions of spatial accessibility, temporal availability, water quality, and acceptability (turbidity, taste, odor), as well as by the price of water services [30,31]. In our analysis, we assess the degree of access TWM reportedly bring about across the non-pecuniary dimensions of access by establishing the service level or characteristics of tanker water services [4] and comparing their prices to existing alternatives, particularly network water tariffs.

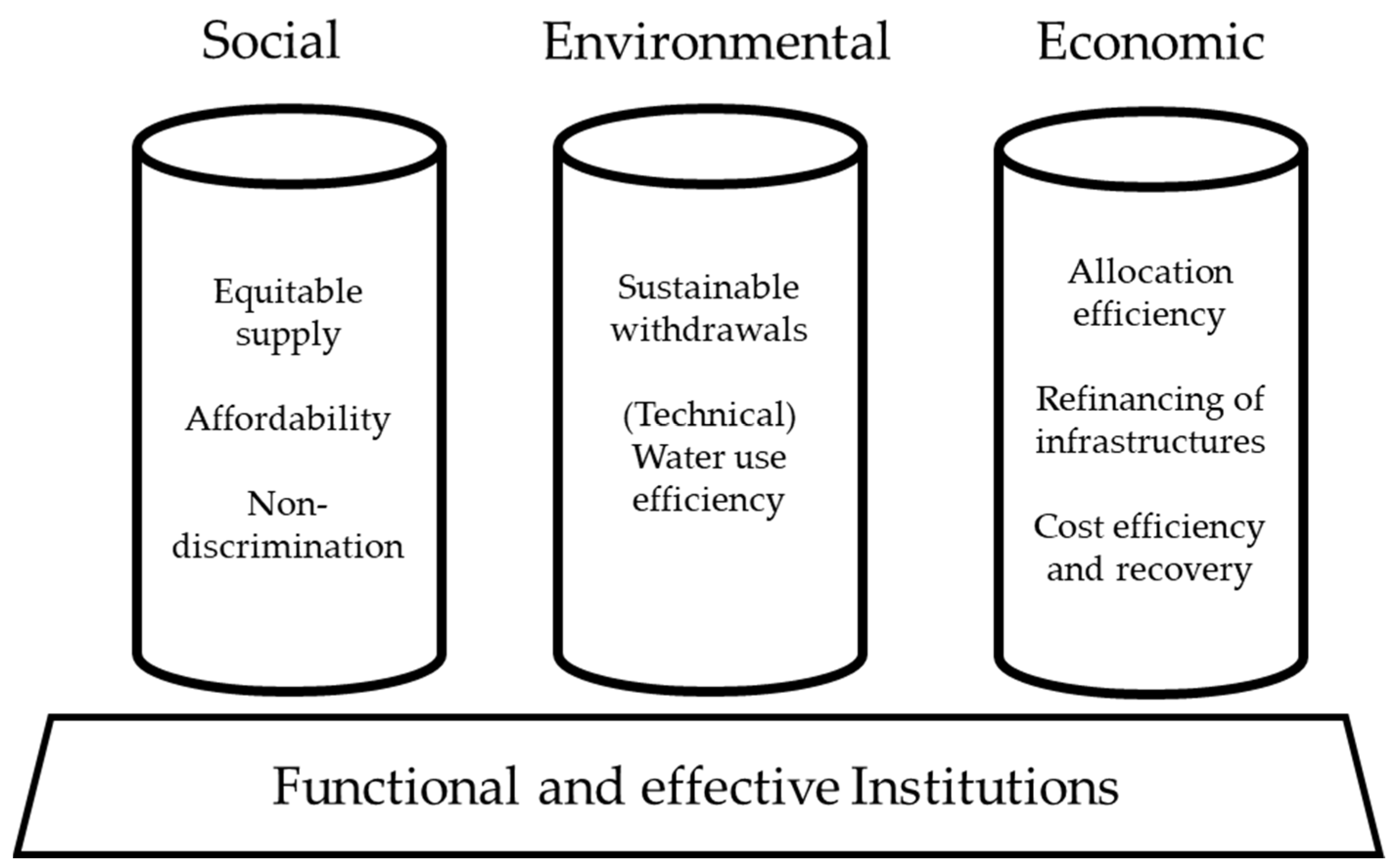

- Normative analysis: In order to make a lasting impact, access has to be sustainable [26,27]. This includes balancing social concerns such as equitable and affordable supply with sustainable withdrawals of water resources as well as sufficient refinancing and economic efficiency of water services provision, from both a short-run and long-run perspective [20]. Using existing sustainability objectives of water policy and literature on what normative concepts such as equitable and affordable supply may entail, we assess to what extent available case studies can provide insights about the sustainability implications of TWM. Given that the balancing of different sustainability objectives hinges on functional and effective institutions [32], we also gather insights from the TWM literature about existing governance structures and challenges within TWM.

2. Sustainability Impacts of Tanker Water Markets: Concepts of Sustainable Access

2.1. Service Levels and Access

2.2. Sustainability Objectives of Water Policy

2.2.1. Affordability of Services

2.2.2. Equitable Supply of Services

2.2.3. Sustainable Withdrawals of Freshwater

2.2.4. Efficiency of Water Services Provision and Re-Financing of Infrastructures

2.2.5. Functional and Effective Institutions

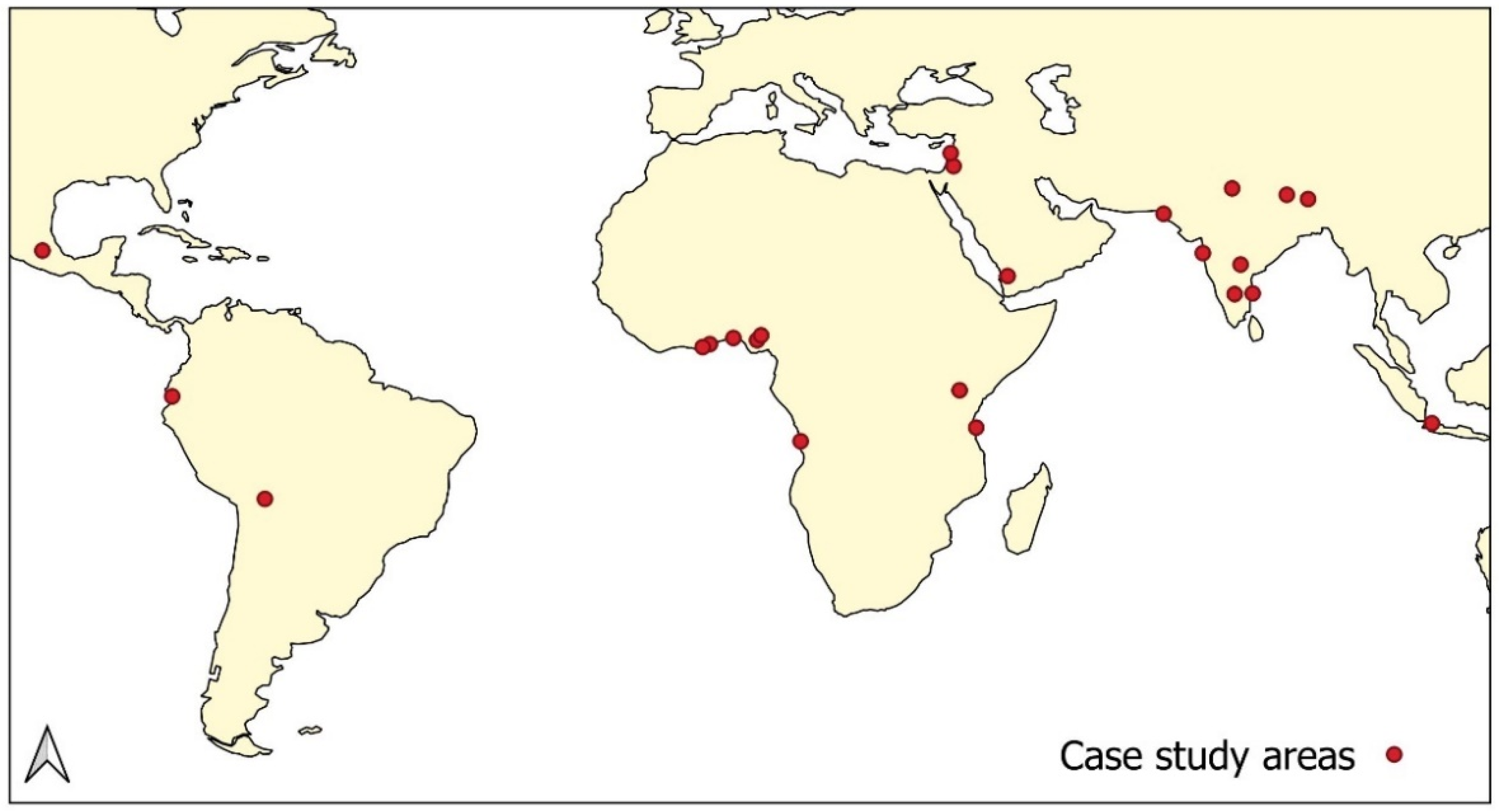

3. Literature Review and Data Acquisition

4. Results

4.1. Outcome of Literature Review

4.2. Contexts of TWM

4.3. Market Characteristics and Conduct

4.3.1. Water Sources, Supply Chain, and Customers

4.3.2. Ownership, Competition, and Pricing

4.4. Service Levels in TWM

4.4.1. Spatial Accessibility

4.4.2. Temporal Availability

4.4.3. Quality and Acceptability

4.4.4. Prices

4.5. Normative Assessments: Sustainability Impacts of TWM

4.5.1. Affordability of TW Services

4.5.2. Equitable Supply

4.5.3. Sustainable Withdrawals

4.5.4. Efficiency of Water Services Provision and Re-Financing of Infrastructures

4.5.5. Functional and Effective Institutions

- Formal institutions and regulations for TWM, such as licensing requirements of providers or quality regulations, exist in seven out of 14 locations and are partially enforced. In all of the studied areas, however, there was evidence of informal or illegal operators working alongside these formal TWM. In Kathmandu, for instance, Shrestha and Shukla [73] reported that although a regulatory entity for TWM was created years ago, most TW providers were unaware it existed. The lack of adequate regulation and enforcement was reported to result in providers not adhering to hygiene standards or obtaining water quantities from contaminated sources, e.g., [76]. In Luanda, the public utility provided a water treatment station at which TW providers must chlorinate water quantities before selling them, but quality checks were only performed on those who voluntarily stopped, which were the minority [130].

- In six out of 14 case study areas, tanker water provision is a legal activity, but there are no formal institutions or regulations governing the provision of tanker water services [17,74,77,107,115]. Alba et al. [77], for instance, reported that a guideline for tanker water services has existed as a draft document for a decade but has not been passed officially.

- In one case, the tanker water market was found to be illegal, but there is no effective enforcement preventing the provision of tanker water services [119].

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Tanker water services are usually rendered at high service levels, which may otherwise be unattainable in the area. This is particularly the case for temporal availability and spatial accessibility of the service, which are frequently higher than those of alternatives such as piped network supply. The evidence for water quality is mixed: It was found to be below international standards for drinking water in 26% of case study areas, but in others reported it to be comparable or even better than other options. Tanker water services come at a higher price for end consumers and can reflect high service levels or performance in terms of particular “access” categories. Their market emergence thus indicates existing gaps in water services provision, particularly the deficiencies of underfinanced public piped water supply.

- Frequently, TWM arise in response to a highly heterogeneous supply of network services, which often do not reach low-income communities at the fringe of cities to a sufficient degree. Tanker water services fill this gap, but their prices exceed (subsidized) network tariffs considerably. Piped water networks achieve a more technically efficient transport of water quantities with a greater up-front investment and benefit from positive network effects, and are often characterized by subsidized tariff structures that do not achieve full cost recovery. The per-unit prices of tanker water services, on the other hand, are subject to steep increases in marginal costs of provision and in dependence of transportation distance. Final market prices therefore vary spatially and between water users, though usually not due to discriminatory practices. Tanker water services are thus unlikely to “fix” existing issues with unequal water supply and are not affordable for all water users. Ensuring equitable and affordable water services for all is commonly considered a government responsibility, and political action may be required to achieve it. Income transfers to those depending exclusively on TWM can constitute a short-term solution. As the availability of storage typically reduces the per-unit prices paid for tanker water and increases the time span, intermittent network supply can be used to meet water needs. In-kind support with large storage containers may also be a considerable option to support low-income households. In the long run, improving and extending piped services may address the social dimensions of sustainable access.

- The review indicated that some TWM are embedded in systems where renewable supply and demand for water quantities are not in balance. In such cases, TWM can contribute to unsustainable resource consumption, but in a system of multiple competing resources uses and often poor governance, TWM themselves are not exclusively “responsible”.

- There are different institutional arrangements governing TWM, ranging from licensing and quality requirements or the monitoring of resource extraction, to entirely unregulated markets. Due to the frequently informal and decentralized nature of TWM, appropriate enforcement of regulation has proven to be challenging.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Characteristic | Data Type | |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual info | Climate | Köppen classification |

| Existing network water presence | Y/N | |

| Dwellings with in-house access to piped water | % | |

| Network water supply frequency | text | |

| Other available water services | text | |

| Population density | pp/km2 | |

| Usage characteristics of TW | Sole use/substitute/backup | |

| Market share of water market | Share (%) | |

| TW Market | Source of tanker water | Text |

| TW price compared to public supply | Ratio (%) | |

| Tanker water market is: | ||

| -Legal | Text | |

| -Regulated | Text | |

| -Enforced | Text | |

| -Competitive | Text | |

| Seasonality of supply and demand | Y/N | |

| Spatial differentiation | Text | |

| Provider organizations | Text | |

| Type of business ownership | Text | |

| Demographic characteristics of TW drivers | Text | |

| TW price determinants | Text | |

| Organizing of sales | Text | |

| Commercial/industry main TW customers? | Y/N | |

| Impact on sustainable access | Spatial accessibility of service | Text |

| Temporal availability of service | Text | |

| Water quality and acceptability | Text | |

| Sustainability impact attributed to TW, according to concepts and indicators developed in Section 2.2: | Text | |

| -Affordability | ||

| -Equitable supply | ||

| -Sustainable withdrawals of freshwater | ||

| -Efficiency of water services provision and re-financing of infrastructures | ||

| -Functional and effective institutions |

References

- Goldman, M.; Narayan, D. Water crisis through the analytic of urban transformation: An analysis of Bangalore’s hydrosocial regimes. Water Int. 2019, 44, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, S.; John, A.; Barua, A. Whose water? Whose profits? The role of informal water markets in groundwater depletion in peri-urban Hyderabad. Water Policy 2019, 21, 1081–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majuru, B.; Suhrcke, M.; Hunter, P.R. How Do Households Respond to Unreliable Water Supplies? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zozmann, H.; Klassert, C.; Klauer, B.; Gawel, E. Heterogeneity, household co-production, and risks of water services—Water demand of private households with multiple water sources. Water Econ. Policy 2022, 8, 2250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, M.; Schwartz, J. Small-Scale Private Service Providers of Water Supply and Electricity: A Review of Incidence, Structure, Pricing, and Operating Characteristics; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Opryszko, M.C.; Huang, H.; Soderlund, K.; Schwab, K.J. Data gaps in evidence-based research on small water enterprises in developing countries. J. Water Health 2009, 7, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellén, M.; McGranahan, G. Informal Water Vendors and the Urban Poor; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, K.; Tukai, R. Services and Supply Chains: The Role of the Domestic Private Sector in Water Service Delivery in Tanzania; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wutich, A.; Beresfoord, M.; Carvajal, C. Can informal water vendors deliver on the promise of a human right to water? Results from Cochabamba, Bolivia. World Dev. 2016, 79, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren, H.; Robertson, S.A. Access to Water in the Slums of Sub-Saharan Africa. Dev. Policy Rev. 2011, 29, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keener, S.; Luengo, M.; Banerjee, S. Provision of Water to the Poor in Africa: Experience with Water Standposts and the Informal Water Sector; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McGranahan, G.; Njiru, C.; Albu, M.; Smith, M.D.; Mitlin, D. How Small Water Enterprises Can Contribute to the Millennium Development Goals: Evidence from Dar es Salaam, Nairobi, Khartoum and Accra; Water, Engineering and Development Centre, Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Franceys, R.; Gerlach, E. Regulating Water and Sanitation for the Poor: Economic Regulation for Public and Private Partnerships; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 1136558888. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, E.L.; Garrick, D.E. The diversity of water markets: Prospects and perils for the SDG agenda. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigel, K.; Klassert, C.; Zozmann, H.; Talozi, S.; Klauer, B.; Gawel, E. Impacts of private tanker water markets on sustainable urban water supply: An empirical study of Amman, Jordan. UFZ Rep. 2017, 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raina, A.; Gurung, Y.; Suwal, B. Equity impacts of informal private water markets: Case of Kathmandu Valley. Water Policy 2020, 22, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, L. Informal water markets and willingness to pay for water: A case study of the urban poor in Chennai City, India. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2015, 31, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braimah, I.; Obeng Nti, K.; Amponsah, O. Poverty Penalty in Urban Water Market in Ghana. Urban Forum 2018, 29, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, M. ‘Mafias’ in the waterscape: Urban informality and everyday public authority in Bangalore. Water Altern. 2014, 7, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for economic co-operation and development. Pricing Water Resources and Water and Sanitation Services; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010; ISBN 978-92-64-08346-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, A.G.; López, F.M. Water insecurity among the urban poor in the peri-urban zone of Xochimilco, Mexico City. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2009, 8, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Gorelick, S.M.; Goulder, L. A hydrologic-economic modeling approach for analysis of urban water supply dynamics in Chennai, India. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, S.; Lechtenfeld, T.; Meier, K.; Rieckmann, J. Impact Evaluation Report: Water Supply and Sanitation in Provincial Towns in Yemen: Courant Research Centre: Poverty, Equity and Growth—Discussion Papers, No. 102. 2011. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/90483 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Schneider, F.; Enste, D.H. Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 77–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, D.E.; Hanemann, M.; Hepburn, C. Rethinking the economics of water: An assessment. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Bretschneider, W. Specification of a human right to water: A sustainability assessment of access hurdles. Water Int. 2017, 42, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Bretschneider, W. Sustainable Access to Water for All: How to Conceptualize and to Implement the Human Right to Water. J. Eur. Environ. Plan Law 2016, 13, 190–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Water. Sustainable Development Goal 6: Synthesis Report on Water and Sanitation; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- General Comment, No. 15. The Right to Water; United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Ed.; United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gawel, E.; Bretschneider, W. Content and Implementation of a Right to Water: An Institutional Economics Approach; Metropolis: Marburg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 3731612089. [Google Scholar]

- De Albuquerque, C. Realizing the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation: A Handbook by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation; United Nations: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Learning from National Policies Supporting MDG Implementation: World Economic and Social Survey 2014/2015; World Economic and Social Survey 2014/2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K. Archipelagos and networks: Urbanization and water privatization in the South. Geogr. J. 2003, 169, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, K.; Kooy, M.; Shofiani, N.E.; Martijn, E.-J. Governance failure: Rethinking the institutional dimensions of urban water supply to poor households. World Dev. 2008, 36, 1891–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Bain, R.; Bartram, J.; Gundry, S.; Pedley, S.; Wright, J. Water safety and inequality in access to drinking-water between rich and poor households. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, A.; Ahmed, N. Intimate infrastructures: The rubrics of gendered safety and urban violence in Kerala, India. Geoforum 2020, 110, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO & UNICEF. JMP Methodology: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Available online: https://washdata.org/report/jmp-methodology-2017-update (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Rawas, F.; Bain, R.; Kumpel, E. Comparing utility-reported hours of piped water supply to households’ experiences. Npj Clean Water 2020, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpel, E.; Nelson, K.L. Intermittent Water Supply: Prevalence, Practice, and Microbial Water Quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriarty, P.; Batchelor, C.; Fonseca, C.; Klutse, A.; Naafs, A.; Nyarko, K.; Pezon, C.; Potter, A.; Reddy, R.; Snehalatha, M. Ladders for Assessing and Costing Water Service Delivery; IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre: Hague, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Onjala, J.; Ndiritu, S.W.; Stage, J. Risk perception, choice of drinking water and water treatment: Evidence from Kenyan towns. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2014, 4, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, D.E.; Tarawneh, T.; Abdel-Khaleq, R.; Lund, J.R. Modeling integrated water user decisions in intermittent supply systems. Water Resour. Res. 2007, 43, W07425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; MacDonald, M.C.; Chan, T.; Kearton, A.; Shields, K.F.; Bartram, J.K.; Hadwen, W.L. Multiple Household Water Sources and Their Use in Remote Communities With Evidence From Pacific Island Countries. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 9106–9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zozmann, H.; Klassert, C.; Klauer, B.; Gawel, E. Water Procurement Time and Its Implications for Household Water Demand—Insights from a Water Diary Study in Five Informal Settlements of Pune, India. Water 2022, 14, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 9241549955. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Buurman, J.; van Ginkel, K.C.H. Urban water security: A review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 53002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H. Water in crisis: Paths to sustainable water use. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.Y. Sustainable, efficient, and equitable water use: The three pillars under wise freshwater allocation. WIREs Water 2014, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.M.; Varis, O. Integrated water resources management: Evolution, prospects and future challenges. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2005, 1, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C.; Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, L.; Behrens, P.; de Koning, A.; Heijungs, R.; Sprecher, B.; Tukker, A. Trade-offs between social and environmental Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 90, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, D. Possible adverse effects of increasing block water tariffs in developing countries. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 1992, 41, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerich, K. A critical review of the concept of equity to support water allocation at various scales in the Amu Darya basin. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2007, 21, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, J.; Ingram, H.; Perry, R.W. The importance of equity and the limits of efficiency in water resources. In Water, Place, and Equity; Whiteley, J., Ingram, H., Perry, R.W., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–32. ISBN 9780262286107. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The institutions of governance. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, S. How (Not) to measure institutions. J. Inst. Econ. 2013, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. A transaction cost theory of politics. J. Theor. Politics 1990, 2, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. An agenda for the study of institutions. Public Choice 1986, 48, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, S.F.; Hope, R. Examining the Economics of Affordability Through Water Diaries in Coastal Bangladesh. Water Econs. Policy 2019, 20, 1950011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Sigel, K.; Bretschneider, W. Affordability of water supply in Mongolia: Empirical lessons for measuring affordability. Water Policy 2013, 15, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawel, E.; Bretschneider, W. Affordability as an Institutional Obstacle to Water-Related Price Reforms. In Studies on the Agricultural and Food Sector in Central and Eastern Europe; Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Central and Eastern Europe: Halle, Germany, 2011; Volume 58. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, G. Monitoring “Affordability” of Water and Sanitation Services after 2015: Review of Global Indicator Options; United Nations Office for the High Commission for Human Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miniaci, R.; Scarpa, C.; Valbonesi, P. Measuring the affordability of basic public utility services in Italy. G. Degli Econ. E Ann. Di Econ. 2008, 67, 185–230. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, R.U. Why do the poor pay more? Exploring the poverty penalty concept. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, Y.; Zhao, J.; Kumar KC, B.; Wu, X.; Suwal, B.; Whittington, D. The costs of delay in infrastructure investments: A comparison of 2001 and 2014 household water supply coping costs in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 7078–7102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarulzaman, A.; de Jong, E.; Smits, J. Hidden water affordability problems revealed in developing countries. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2019, 145, 5019006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postel, S.L.; Daily, G.C.; Ehrlich, P.R. Human appropriation of renewable fresh water. Science 1996, 271, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.J.; Bailey, R.M.; Cullis, J.D.S.; New, M.G. Spatial inequality in water access and water use in South Africa. Water Policy 2018, 20, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.L.; Libecap, G.D. Environmental Markets: A Property Rights Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 1107010225. [Google Scholar]

- Easter, K.W.; Rosegrant, M.W.; Dinar, A. Formal and Informal Markets for Water: Institutions, Performance, and Constraints; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 1351159283. [Google Scholar]

- Grafton, R.Q.; Libecap, G.; McGlennon, S.; Landry, C.; O’Brien, B. An integrated assessment of water markets: A cross-country comparison. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2020, 5, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. In Uncertainty in Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, D.; Shukla, A. Private water tanker operators in Kathmandu. In Globalization of Water Governance in South Asia; Narain, V., Goodrich, C.G., Chourey, J., Prakash, A., Eds.; Routledge: Delhi, India, 2018; pp. 256–272. ISBN 9781315734187. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, K.; Massoud, M.; Alameddine, I.; El-Fadel, M. The role of the water tankers market in water stressed semi-arid urban areas: Implications on water quality and economic burden. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba, R.; Bruns, A.; Bartels, L.; Kooy, M. Water Brokers: Exploring Urban Water Governance through the Practices of Tanker Water Supply in Accra. Water 2019, 11, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmadyanto, H.; van Dijk, M.P.; Kwarteng, S.O. Mapping pro-poor water supply services: What are the technical and institutional options for the utility and private provision in Accra? IJW 2016, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, R.; Kooy, M.; Bruns, A. Conflicts, cooperation and experimentation: Analysing the politics of urban water through Accra’s heterogeneous water supply infrastructure. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2020, 5, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutu, R.A.; Stoler, J. Urban but off the grid: The struggle for water in two urban slums in greater Accra, Ghana. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2016, 35, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, E.F.; Owusu, A.B.; Owusu, G.; Eshun, F. Accra’s poverty trap: Analysing water provision in urban Ghana. J. Soc. Sci. Policy Implic. 2014, 2, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Peloso, M.; Morinville, C. ‘Chasing for water’: Everyday practices of water access in peri-urban Ashaiman, Ghana. Water Altern. 2014, 7, 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sarpong, K.; Abrampah, K.M. Small Water Enterprises in Africa 4—Ghana: A Study of Small Water Enterprises in Accra; Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alba, R.; Bartels, L.E. Featuring Water Infrastructure, Provision and Access in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area: WaterPower Working Paper, No. 6. Governance and Sustainability; Universität Trier: Trier, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stoler, J. Spatial Patterns of Water Insecurity in a Developing City: Lessons from Accra, Ghana. Ph.D. Thesis, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Klassert, C.; Sigel, K.; Gawel, E.; Klauer, B. Modeling residential water consumption in Amman: The role of intermittency, storage, and pricing for piped and tanker water. Water 2015, 7, 3643–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zozmann, H.; Klassert, C.; Sigel, K.; Gawel, E.; Klauer, B. Commercial Tanker Water Demand in Amman, Jordan—A Spatial Simulation Model of Water Consumption Decisions under Intermittent Network Supply. Water 2019, 11, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, D.E.; Talozi, S.; Lund, J.R. Intermittent water supplies: Challenges and opportunities for residential water users in Jordan. Water Int. 2008, 33, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, E.; Franceys, R. Regulating water services for the poor: The case of Amman. Geoforum 2009, 40, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, D.; Talozi, S. Tankers, Wells, Pipes and Pumps: Agents and Mediators of Water Geographies in Amman, Jordan. Water Altern. 2018, 11, 916–932. [Google Scholar]

- Orgill-Meyer, J.; Jeuland, M.; Albert, J.; Cutler, N. Comparing Contingent Valuation and Averting Expenditure Estimates of the Costs of Irregular Water Supply. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigel, K.; Klassert, C.; Zozmann, H.; Talozi, S.; Klauer, B.; Gawel, E. Socioeconomic surveys on private tanker water markets in Jordan: Objectives, design and methodology. UFZ Discuss. Pap. 2017, 4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wildman, T. Water Market System in Balqa, Zarqa, & Informal Settlements of Amman & the Jordan Valley. 2013. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/38742 (accessed on 21 July 2017).

- Klasen, S.; Lechtenfeld, T.; Meier, K.; Rieckmann, J. Benefits trickling away: The health impact of extending access to piped water and sanitation in urban Yemen. J. Dev. Eff. 2012, 4, 537–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, N. Urban Water Access: Formal and Informal Markets: A Case Study of Bengaluru; Working Paper Series; Tata Institute of Social Science: Hyderabad, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Awere, E.; Anornu, G.K. The contribution of water tanker operations to the health of water consumers in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 7, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, P.A.; Dwamena-Boateng, P.; Ntiamoah-Asare, D.J. Alternative drinking water supply in low-income urban settlements using tankers: A quality assessment in Cape Coast, Ghana. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2010, 12, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Gorelick, S.M.; Goulder, L. Factors determining informal tanker water markets in Chennai, India. Water Int. 2010, 35, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Seto, K.C.; Emerson, R.; Gorelick, S.M. The impact of urbanization on water vulnerability: A coupled human–environment system approach for Chennai, India. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.K.; Sasidharan, S. Measuring affordability of access to clean water: A coping cost approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakyaga, F.; Kyessi, A.G.; Msami, J.M. Households’ Assessment of the Water Quality and Services of Multi-model Urban Water Supply System in the Informal Settlements of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2018, 12, 362–381. [Google Scholar]

- Rajasingham, A.; Hardy, C.; Kamwaga, S.; Sebunya, K.; Massa, K.; Mulungu, J.; Martinsen, A.; Nyasani, E.; Hulland, E.; Russell, S.; et al. Evaluation of an Emergency Bulk Chlorination Project Targeting Drinking Water Vendors in Cholera-Affected Wards of Dar es Salaam and Morogoro, Tanzania. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nganyanyuka, K.; Martinez, J.; Wesselink, A.; Lungo, J.H.; Georgiadou, Y. Accessing water services in Dar es Salaam: Are we counting what counts? Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellén, M. From public pipes to private hands: Water access and distribution in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Ph.D. Thesis, Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Truelove, Y. Gray Zones: The Everyday Practices and Governance of Water beyond the Network. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 1758–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, M. ‘Water mafia’ politics and unruly informality in Delhi’s unauthorised colonies. In Water, Creativity and Meaning; Roberts, L., Phillips, K., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 188–203. ISBN 9781315110356. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, U.D.; Choudhary, B.K. Reconfiguring urban waterscape: Water kiosks in Delhi as a new governance model. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2020, 10, 996–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivani, D. Private Supply of Water in Delhi; Working Papers: Delhi, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olajuyigbe, A.E.; Rotowa, O.; Adewumi, I. Water Vending in Nigeria—A Case Study of Festac Town, Lagos, Nigeria. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 229. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E.A. The contradictions of urban water provision: A study of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Third World Plan. Rev. 1995, 17, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Swyngedouw, E. Social Power and the Urbanization of Water: Flows of Power; Oxford University Press Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 0198233914. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, A. The periurban water security problem: A case study of Hyderabad in Southern India. Water Policy 2014, 16, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Singh, S.; Brouwer, L. Water Transfer from Peri-urban to Urban Areas. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2015, 6, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovei, L.; Whittington, D. Rent-extracting behavior by multiple agents in the provision of municipal water supply: A study of Jakarta, Indonesia. Water Resour. Res. 1993, 29, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, R. Water markets, market reform and the urban poor: Results from Jakarta, Indonesia. World Dev. 1994, 22, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Namchu, C.; Nyima, K.; Luitel, M.; Singh, S.; Goodrich, C.G. Water management systems of two towns in the Eastern Himalaya: Case studies of Singtam in Sikkim and Kalimpong in West Bengal states of India. Water Policy 2020, 22, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D. Feminist Solidarity? Women’s Engagement in Politics and the Implications for Water Management in the Darjeeling Himalaya. Mt. Res. Dev. 2014, 34, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Sohail, M. Alternate water supply arrangements in peri-urban localities: Awami(people’s) tanks in Orangi township, Karachi. Environ. Urban. 2003, 15, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Sohail, M. Stakeholders’ response to the private sector participation of water supply utility in Karachi, Pakistan. Water Policy 2004, 6, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rafi, M.M.; Lodi, S.H.; Hasan, N.M. Corruption in Public Infrastructure Service and Delivery. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2012, 17, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R. The Role of Private Vending in Developing Country Water Service Delivery: The Case of Karachi, Pakistan. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury, A. Can Private Water Vendors Help Meet the Millennium Development Goals?—A Study of Karachi City Urban Water Market; Working Paper; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, D.; Akhter, M.; Nasrallah, N. Understanding Pakistan’s Water-Security Nexus; United States Institute of Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guragai, B.; Takizawa, S.; Hashimoto, T.; Oguma, K. Effects of inequality of supply hours on consumers’ coping strategies and perceptions of intermittent water supply in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, B.; Ghaju Shrestha, R.; Tandukar, S.; Bhandari, D.; Thakali, O.; Sherchand, J.B.; Haramoto, E. Detection of Pathogenic Viruses, Pathogen Indicators, and Fecal-Source Markers within Tanker Water and Their Sources in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Pathogens 2019, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, R.; Thapa, B.; Shrestha, S.; Shindo, J.; Ishidaira, H.; Kazama, F. Water Price Optimization after the Melamchi Water Supply Project: Ensuring Affordability and Equitability for Consumer’s Water Use and Sustainability for Utilities. Water 2018, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, R.; Shrestha, A.; Karki, K.; Shukla, A. Groundwater extraction: Implications on local water security of peri-urban area of Kathmandu Valley. Nepal J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 14, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, O.C.; Khanal, A.; Pradhan, N. The pain of water: A household perspective of water insecurity and inequity in the Kathmandu Valley. Water Policy 2020, 22, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.; Zhao, J.; Wu, X.; Kunwar, L.; Whittington, D. The structure of water vending markets in Kathmandu, Nepal. Water Policy 2019, 21, 50–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, A. Informal water markets and community management in peri-urban Luanda, Angola. Water Int. 2018, 43, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, A.; Baptista, A.C. Community Management and the Demand for ‘Water for All’ in Angola’s Musseques. Water 2020, 12, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, A.; Mulenga, M. Water Service Provision for the Peri-Urban Poor in Post-Conflict Angola; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, A. Water Resource Management Under a Changing Climate in Angola’s Coastal Settlements; IIED Working Paper: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep02730.pdf?acceptTC=true&coverpage=false&addFooter=false (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Development Workshop Angola. The Informal Peri-Urban Water Sector in Luanda. Final Report. 2009. Available online: http://dw.angonet.org/content/papers-dw (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Development Workshop Angola. Water Supply and Sanitation in Luanda Informal Sector Study and Beneficiary Assessment. Final Report—Prepared for the World Bank. 1995. Available online: https://www.dw.angonet.org/forumitem/water-supply-and-sanitation-luanda-informal-sector-study-and-beneficiary-assessment-0 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Baisa, B.; Davis, L.W.; Salant, S.W.; Wilcox, W. The welfare costs of unreliable water service. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 92, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Desai, R.; McFarlane, C. Water wars in Mumbai. Public Cult. 2013, 25, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitlin, D.; Beard, V.A.; Satterthwaite, D.; Du, J. Unaffordable and Undrinkable: Rethinking Urban Water Access in the Global South; Working Paper: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ain, Q.; Kannan, S. Moving Toward Universal Water & Sanitation Access: A Ground Assessment of WASH Realities in COVID-19 Times. 2020. Available online: http://panihaqsamiti.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Report-Impact-of-COVID-19-and-lockdown-on-WASH-in-Mumbais-informal-settlements-VKA-PHS-CPD-compressed.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Nnaji, C.C.; Eluwa, C.; Nwoji, C. Dynamics of domestic water supply and consumption in a semi-urban Nigerian city. Habitat Int. 2013, 40, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochungo, E.A.; Ouma, G.O.; Obiero, J.P.O.; Odero, N.A. The Implication of Unreliable Urban Water Supply Service: The Case of Vendor Water Cost in Langata Sub County, Nairobi City, Kenya. JWARP 2019, 11, 896–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A. Informal water vendors and the urban poor: Evidence from a Nairobi slum. Water Int. 2020, 45, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, D.; Lauria, D.T.; Mu, X. A study of water vending and willingness to pay for water in Onitsha, Nigeria. World Dev. 1991, 19, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Klassert, C.; Selby, P.; Lachaut, T.; Knox, S.; Avisse, N.; Harou, J.; Tilmant, A.; Klauer, B.; Mustafa, D.; et al. A coupled human-natural system analysis of freshwater security under climate and population change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020431118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awepuga, F.A. Water Scarcity in the Tamale Metropolis and the Role of the Informal Water Sector in Urban Water Supply. Master’s Thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kwame, Ghana, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McGranahan, G.; Owen, D.L. Local Water Companies and the Urban Poor: Human Settlements Discussion Paper Series. Theme: Water-4; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ataguba, C.O. An assessment of the informal water sector in the provision of water supply services to consumers in Idah town, Nigeria. In Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Services Beyond 2015: Improving Access and Sustainability, Proceedings of the 38th WEDC International Conference, Loughborough, UK, 27–31 July 2015; Shaw, R.J., Ed.; WEDC, Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, P.H. The human right to water. Water Policy 1998, 1, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, L.C.; Kelner-Levine, E.; Eckelman, M.J.; McCarty, K.M.; Elimelech, M. Water flows, energy demand, and market analysis of the informal water sector in Kisumu, Kenya. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 87, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, P. Water Supply in Karachi: Situation, Issues, Priority Issues and Solutions; Orangi Pilot Project—Research and Training Institute: Karachi, Pakistan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garrick, D.; Moore, M.S.; Brozovic, N.; Iseman, T.; O’Donnell, E. Informal Water Markets in an Urbanising World: Some Unanswered Questions; Washington, DC, USA. 2019. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/358461549427540914/informal-water-markets-in-an-urbanising-world-some-unanswered-questions (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Klassert, C.; Gawel, E.; Sigel, K.; Klauer, B. Sustainable Transformation of Urban Water Infrastructure in Amman, Jordan—Meeting Residential Water Demand in the Face of Deficient Public Supply and Alternative Private Water Markets. In Urban Transformations: Sustainable Urban Development through Resource Efficiency, Quality of Life and Resilience; Kabisch, S., Koch, F., Gawel, E., Haase, A., Knapp, S., Krellenberg, K., Nivala, J., Zehnsdorf, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 93–115. ISBN 3319593242. [Google Scholar]

- Pangare, G.; Pangare, V. Informal Water Vendors and Service Providers in Uganda: The Ground Reality. 2008. Available online: https://sswm.info/sites/default/files/reference_attachments/PANGARE%20&%20PANGARE%202008%20Informal%20Water%20Vendors%20and%20Service%20Providers%20in%20Uganda.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2020).

| Tanker Water Keywords | Market Keywords |

|---|---|

| tanker truck(s) | water market(s) |

| water tanker(s) tanker water water truck(s) | informal water water vendor(s) |

| Case Study Area | Peer-Reviewed Articles | Supplementary (Grey) Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Accra, Ghana | [18,75,76,77,78,79,80] | [81,82,83] |

| Amman, Jordan | [84,85,86,87,88,89] | [15,90,91] |

| Amran, Yemen | [92] | [23] |

| Bangalore, India | [1,19] | [93] |

| Beirut, Lebanon | [74] | |

| Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana | [94,95] | |

| Chennai, India | [17,22,96,97,98] | |

| Cochabamba, Bolivia | [9] | |

| Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | [99,100] | [8,101,102] |

| Delhi, India | [103,104,105] | [106] |

| Festac Town, Lagos, Nigeria | [107] | |

| Guayaquil, Ecuador | [108] | [109] |

| Hyderabad, India | [110,111] | |

| Jakarta, Indonesia | [112,113] | |

| Kalimpong, India | [114,115] | |

| Karachi, Pakistan | [116,117,118] | [119,120,121] |

| Kathmandu Valley, Nepal | [16,73,122,123,124,125,126,127] | |

| Luanda, Angola | [128,129] | [130,131,132,133] |

| Mexico City, Mexico | [21,134] | |

| Mumbai, India | [135] | [136,137] |

| Nsukka, Nigeria | [138] | |

| Nairobi, Kenya | [139,140] | |

| Onitsha, Nigeria | [141] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zozmann, H.; Morgan, A.; Klassert, C.; Klauer, B.; Gawel, E. Can Tanker Water Services Contribute to Sustainable Access to Water? A Systematic Review of Case Studies in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11029. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711029

Zozmann H, Morgan A, Klassert C, Klauer B, Gawel E. Can Tanker Water Services Contribute to Sustainable Access to Water? A Systematic Review of Case Studies in Urban Areas. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):11029. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711029

Chicago/Turabian StyleZozmann, Heinrich, Alexander Morgan, Christian Klassert, Bernd Klauer, and Erik Gawel. 2022. "Can Tanker Water Services Contribute to Sustainable Access to Water? A Systematic Review of Case Studies in Urban Areas" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 11029. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711029

APA StyleZozmann, H., Morgan, A., Klassert, C., Klauer, B., & Gawel, E. (2022). Can Tanker Water Services Contribute to Sustainable Access to Water? A Systematic Review of Case Studies in Urban Areas. Sustainability, 14(17), 11029. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711029