Cultural, Social and Psychological Factors of the Conservative Consumer towards Legal Cannabis Use—A Review since 2013

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

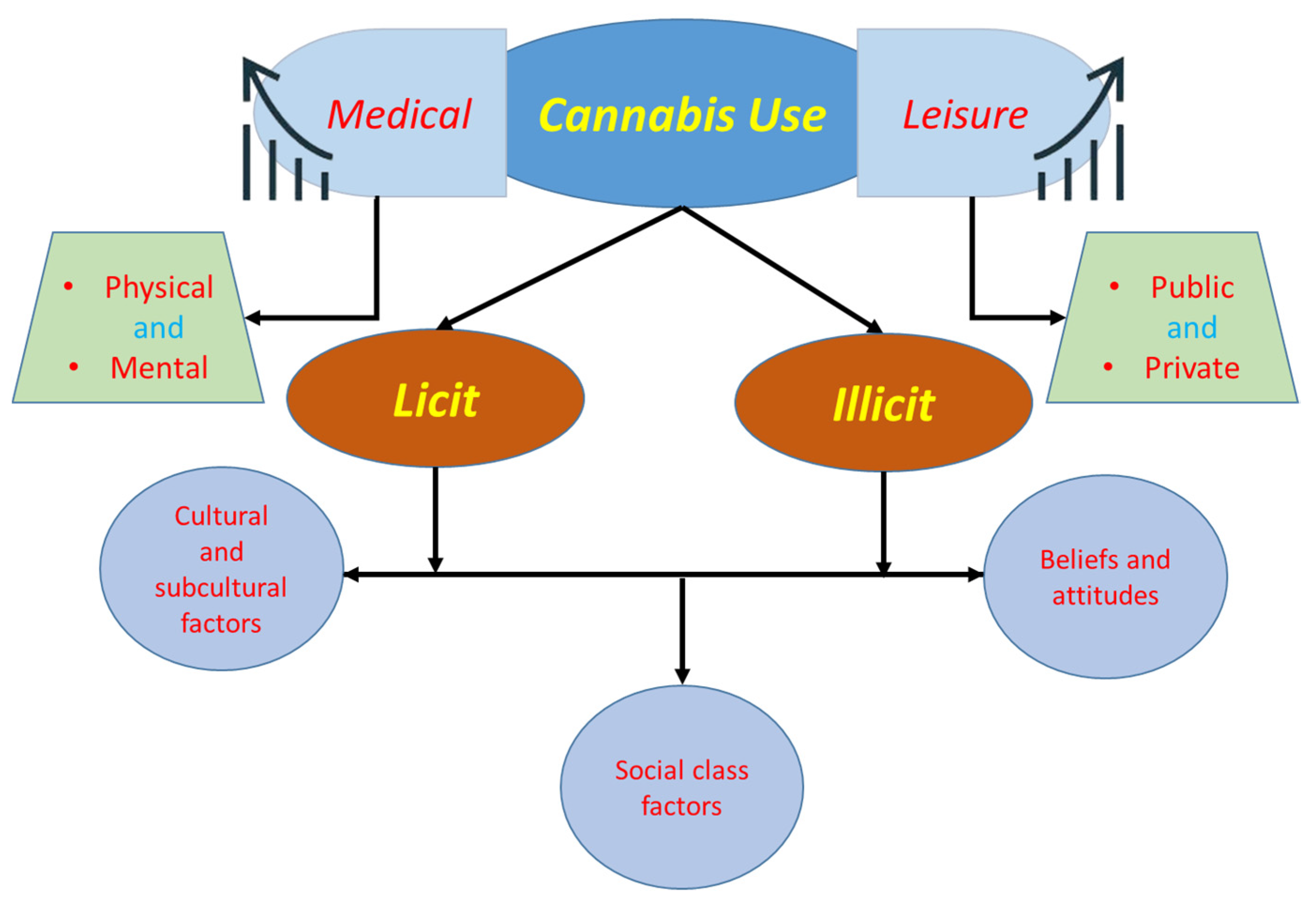

3. Cultural and Subcultural Factors towards Legal Cannabis Use

4. Social Class Factors towards Legal Cannabis Use

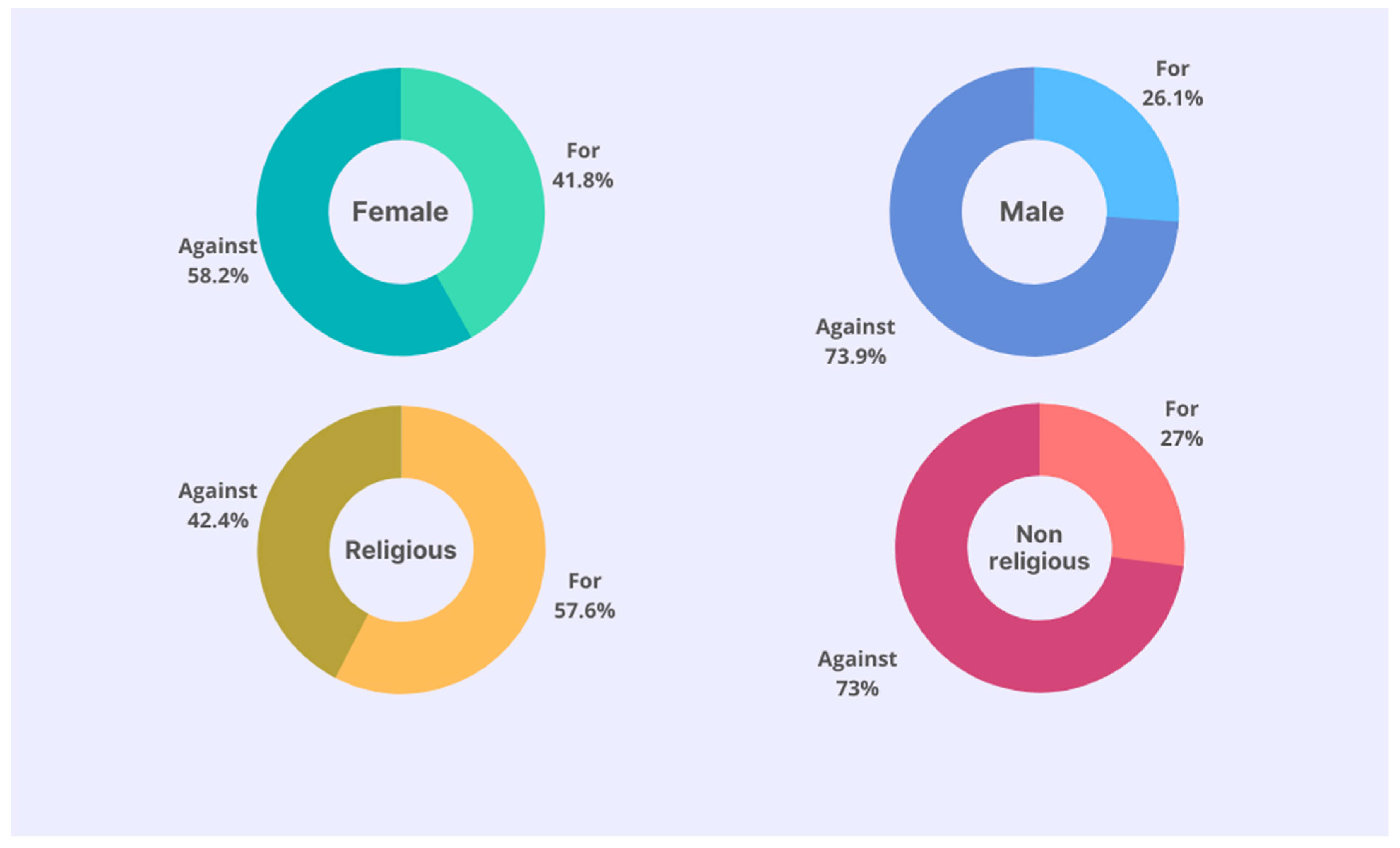

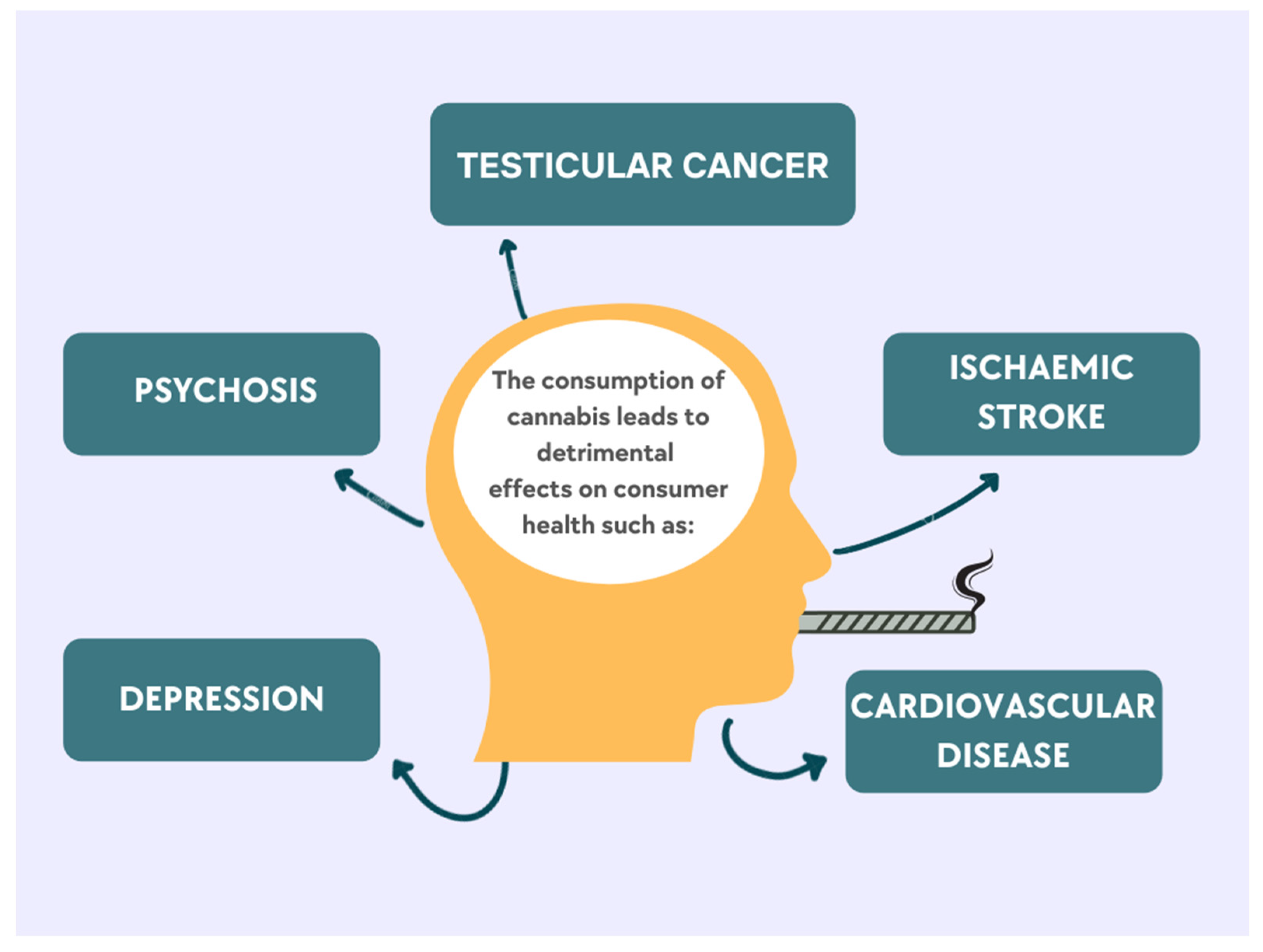

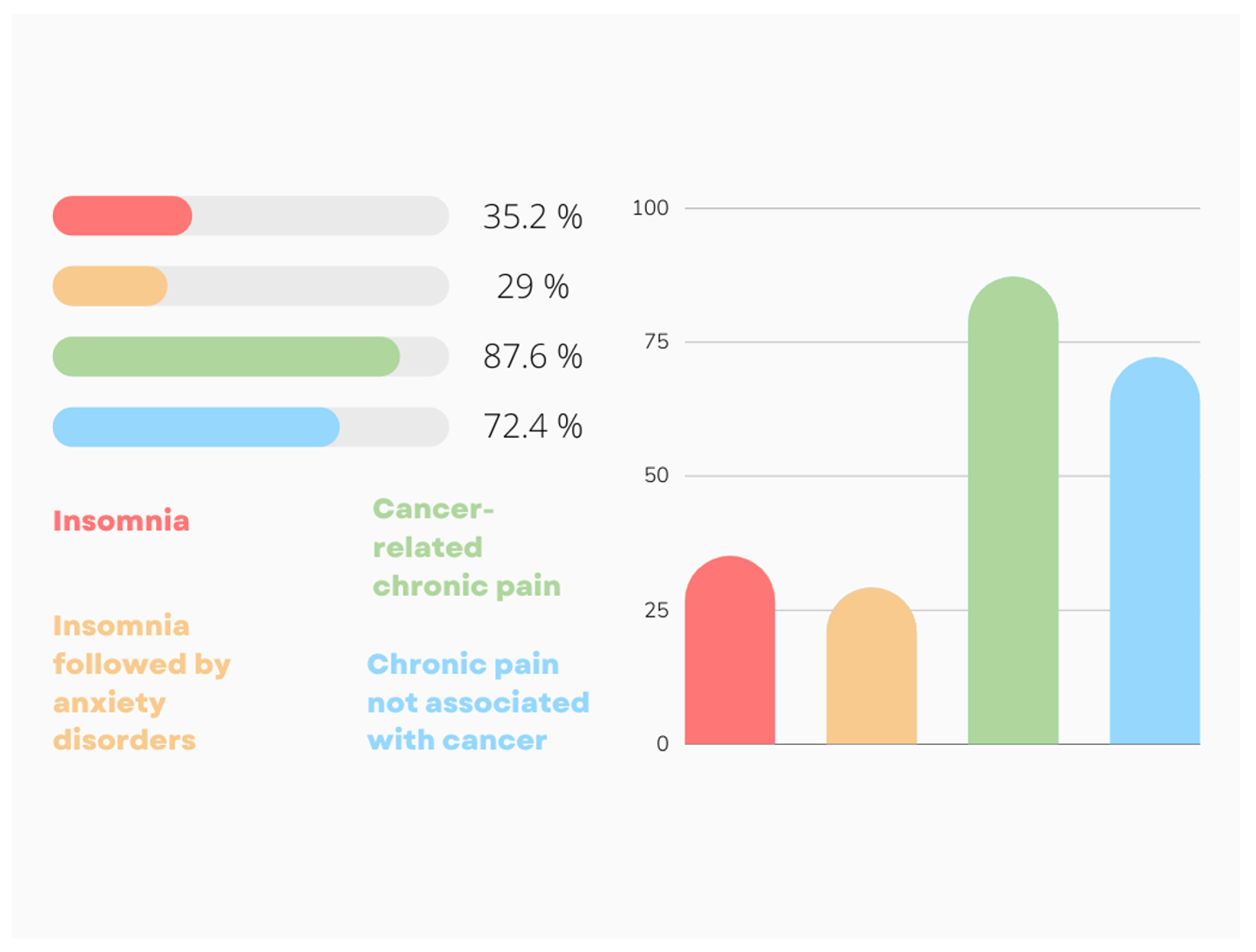

5. Beliefs and Attitudes of Conservative Consumers towards Legal Cannabis Use

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mortensen, T.M.; Moscowitz, L.; Wan, A.; Yang, A. The marijuana user in US news media: An examination of visual stereotypes of race, culture, criminality and normification. Vis. Commun. 2020, 19, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartenberg, A.C.; Holden, P.A.; Bodwitch, H.; Parker-Shames, P.; Novotny, T.; Harmon, T.C.; Hart, S.C.; Beutel, M.; Gilmore, M.; Hoh, E.; et al. Cannabis and the Environment: What Science Tells Us and What We Still Need to Know. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavousi, P.; Giamo, T.; Arnold, G.; Alliende, M.; Huynh, E.; Lea, J.; Lucine, R.; Tillett Miller, A.; Webre, A.; Yee, A.; et al. What do we know about opportunities and challenges for localities from Cannabis legalization? Rev. Policy Res. 2022, 39, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrot, J.A.; Mattingly, M. Economic and Revenue Impact of Marijuana Legalization in NYS A Fresh Look. 2021. Available online: https://cannabislaw.report/new-report-economic-and-revenue-impact-of-marijuana-legalization-in-nys-a-fresh-look/ (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Dillis, C.; Biber, E.; Bodwitch, H.; Butsic, V.; Carah, J.; Parker-Shames, P.; Polson, M.; Grantham, T. Shifting geographies of legal cannabis production in California. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikos, R.A. Interstate Commerce in Cannabis. Leg. Stud. Res. Pap. Ser. 2021, 101, 857. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, T.; Wen, J.; Shan, H. Is Cannabis Tourism Deviant? A Theoretical Perspective. Tour. Rev. Int. 2019, 23, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belackova, V.; Wilkins, C. Consumer agency in cannabis supply—Exploring auto-regulatory documents of the cannabis social clubs in Spain. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 54, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, H.B.; Kaplan, C.D.; Braam, R.V.; Verbraeck, H.T.; de Vries, N.K. The application of the rapid assessment and response methodology for cannabis prevention research among youth in the Netherlands. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiman, A. The Fallacy of a One Size Fits All Cannabis Policy. Humboldt. J. Soc. Relat. 2013, 35, 104–122. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/humjsocrel.35.104 (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Wright, D.W.M. Cannabis and tourism: A future UK industry perspective. J. Tour. Futur. 2019, 5, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayasirisobhon, S. Mechanisms of Action and Pharmacokinetics of Cannabis. Perm. J. 2021, 25, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J. Why Are So Many Countries Now Saying Cannabis Is OK? BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-46374191 (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Weedmaps. Uruguay. Weedmaps. Available online: https://weedmaps.com/learn/laws-and-regulations/uruguay (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Government of Alberta. Cannabis Legalization in Canada. Available online: https://www.alberta.ca/cannabis-legalization-in-canada.aspx#jumplinks-3 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Government of Canada. Cannabis Legalization and Regulation. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/cannabis/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Sabaghi, D. Malta Is to Legalize Cannabis for Personal Use, Social Clubs, But Not Sales. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/dariosabaghi/2021/12/01/malta-is-to-legalize-cannabis-for-personal-use-social-clubs-but-not-sales/?sh=1dc4c95a6c86 (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Government of the Netherlands. Toleration Policy Regarding Soft Drugs and Coffee Shops. Available online: https://www.government.nl/topics/drugs/toleration-policy-regarding-soft-drugs-and-coffee-shops (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Hansen, C.; Alas, H.; Davis, E., Jr. Where Is Marijuana Legal? A Guide to Marijuana Legalization. US News. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/where-is-marijuana-legal-a-guide-to-marijuana-legalization (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Yakowicz, W. U.S. House of Representatives Passes Federal Cannabis Legalization Bill MORE Act. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/willyakowicz/2022/04/01/us-house-of-representatives-pass-federal-cannabis-legalization-bill-more-act/?sh=2afa20d466d7 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Hunter, G.; Bennet, T. Medicinal Cannabis in Australia. Finder. Available online: https://www.finder.com.au/medical-marijuana-australia (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Weedmaps. Australia. Available online: https://weedmaps.com/learn/laws-and-regulations/australia (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Weedmaps. Spain. Available online: https://weedmaps.com/learn/laws-and-regulations/spain (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Pritzker, S. Is Weed Legal in Portugal? The Cannigma. Available online: https://cannigma.com/regulation/portugal-cannabis-laws/ (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Melnick, L. Everything to Know About Cannabis in South Africa. Matador. Available online: https://matadornetwork.com/read/everything-know-cannabis-south-africa/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Parks, K. Drop in Cannabis Prices Creates an Opportunity for Paraguay. Bloomberg. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-01-03/a-drop-in-marijuana-prices-opens-a-door-for-one-small-country (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Osborne, G.B.; Fogel, C. Perspectives on Cannabis Legalization Among Canadian Recreational Users. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2017, 44, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahees, M.; Amarasinghe, H.; Usgodaararachchi, U.; Ratnayake, N.; Tilakarathne, W.M.; Shanmuganathan, S.; Ranaweera, S.; Abeykoon, P. A Sociological Analysis and Exploration of Factors Associated with Commercial Preparations of Smokeless Tobacco Use in Sri Lanka. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagdalyan, A.A.; Oboturova, A.P.; Povetkin, S.N.; Ziruk, I.V.; Egunova, A.; Simonov, A.N. Adaptogens Instead Restricted Drugs Research for an Alternative Itemsto Doping in Sport. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Dubreta, N. Socio-Cultural Context of Drug Use with Reflections to Cannabis Use in Croatia. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. 2013, 11, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hathaway, A.; Mostaghim, A.; Kolar, K.; Erickson, P.G.; Osborne, G. A nuanced view of normalisation: Attitudes of cannabis non-users in a study of undergraduate students at three Canadian universities. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2016, 23, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.L.; Demant, J. “Don’t make too much fuss about it.” Negotiating adult cannabis use. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2017, 24, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen, P.; Karjalainen, K.; Raitasalo, K.; Sorvala, V.-M. School’s in! Predicting teen cannabis use by conventionality, cultural disposition and social context. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2015, 22, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.M.; Boidi, M.F.; Queirolo, R. Saying no to weed: Public opinion towards cannabis legalisation in Uruguay. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2018, 25, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.N.; Newhill, C.E. The role of religiosity as a protective factor against marijuana use among African American, White, Asian, and Hispanic adolescents. J. Subst. Use 2016, 21, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alencar Ramos, G. Political ideology, groupness, and attitudes toward Marijuana legalization. Master’s Thesis, Fundacão Getulio Vargas, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer, B.; MacCoun, R.J. How Medical Marijuana Smoothed the Transition to Marijuana Legalization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.; Cousijn, J.; Filbey, F. Determining Risks for Cannabis Use Disorder in the Face of Changing Legal Policies. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2019, 6, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, N.; Sales, P.; Averill, S.; Murphy, F.; Sato, S.-O.; Murphy, S. Responsible and controlled use: Older cannabis users and harm reduction. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S.; Tolstrup, J.; Thylstrup, B.; Hesse, M. Neutralization and glorification: Cannabis culture-related beliefs predict cannabis use initiation. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2016, 23, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, N.; Milne, B.J.; Jerrim, J. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Adolescent Substance Use: Evidence from Twenty-Four European Countries. Subst. Use Misuse 2019, 54, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerra, G.; Benedetti, E.; Resce, G.; Potente, R.; Cutilli, A.; Molinaro, S. Socioeconomic Status, Parental Education, School Connectedness and Individual Socio-Cultural Resources in Vulnerability for Drug Use among Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, H.A.; van der Maas, M.; Boak, A.; Mann, R.E. Subjective Social Status, Immigrant Generation, and Cannabis and Alcohol Use among Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzelka, B.; Vacek, J.; Gavurova, B.; Kubak, M.; Gabrhelik, R.; Rogalewicz, V.; Bartak, M. Interaction of Socioeconomic Status with Risky Internet Use, Gambling and Substance Use in Adolescents from a Structurally Disadvantaged Region in Central Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.B.; Hill, M.L.; Pardini, D.A.; Meier, M.H. Prevalence and correlates of vaping cannabis in a sample of young adults. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogeberg, O. Correlations between cannabis use and IQ change in the Dunedin cohort are consistent with confounding from socioeconomic status. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4251–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipping, R.R.; Smith, M.; Heron, J.; Hickman, M.; Campbell, R. Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and socio-economic status: Findings from a UK birth cohort. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, G.C.K.; Leung, J.; Quinn, C.; Weier, M.; Hall, W. Socio-economic differentials in cannabis use trends in Australia. Addiction 2018, 113, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charitonidi, E.; Studer, J.; Gaume, J.; Gmel, G.; Daeppen, J.-B.; Bertholet, N. Socioeconomic status and substance use among Swiss young men: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, D.J.; Hsu, H.; Weiss, D.; Fell, D.B.; Walker, M. Trends and correlates of cannabis use in pregnancy: A population-based study in Ontario, Canada from 2012 to 2017. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, M.; Moffitt, T.E.; Meier, M.H.; Harrington, H.; Houts, R.; Ramrakha, S.; Hogan, S.; Poulton, R.; Caspi, A. Persistent Cannabis Dependence and Alcohol Dependence Represent Risks for Midlife Economic and Social Problems. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 4, 1028–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.L.; Tough, S.C. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with illicit drug use among pregnant women with middle to high socioeconomic status: Findings from the All Our Families Cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauffin, K.; Vinnerljung, B.; Fridell, M.; Hesse, M.; Hjern, A. Childhood socio-economic status, school failure and drug abuse: A Swedish national cohort study. Addiction 2013, 108, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.O.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Kosterman, R.; Small, C.M.; Hawkins, J.D. Educational inequalities in the co-occurrence of mental health and substance use problems, and its adult socio-economic consequences: A longitudinal study of young adults in a community sample. Public Health 2013, 127, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.H.; Hill, M.L.; Small, P.J.; Luthar, S.S. Associations of adolescent cannabis use with academic performance and mental health: A longitudinal study of upper middle class youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 156, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.O.; Hill, K.G.; Hartigan, L.A.; Boden, J.M.; Guttmannova, K.; Kosterman, R.; Bailey, J.A.; Catalano, R.F. Unemployment and substance use problems among young adults: Does childhood low socioeconomic status exacerbate the effect? Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 143, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaappila, N.; Marttunen, M.; Fröjd, S.; Lindberg, N.; Kaltiala-Heino, R. Changes in delinquency according to socioeconomic status among Finnish adolescents from 2000 to 2015. Scand. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Psychol. 2019, 7, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloner, B.; Cook, B.L. Blacks and Hispanics Are Less Likely Than Whites to Complete Addiction Treatment, Largely Due to Socioeconomic Factors. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carliner, H.; Delker, E.; Fink, D.S.; Keyes, K.M.; Hasin, D.S. Racial discrimination, socioeconomic position, and illicit drug use among US Blacks. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karriker-Jaffe, K.J. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and substance use by U.S. adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013, 133, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttmannova, K.; Fleming, C.B.; Rhew, I.C.; Alisa Abdallah, D.; Patrick, M.E.; Duckworth, J.C.; Lee, C.M. Dual trajectories of cannabis and alcohol use among young adults in a state with legal nonmedical cannabis. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiburo-Seguel, A.; Vargas, S.; Oyanedel, J.C.; Torres, F.; Vergara, E.; Hough, M. Attitudes towards drug policies in Latin America: Results from a Latin-American Survey. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 41, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- MacQuarrie, A.L.; Brunelle, C. Emerging Attitudes Regarding Decriminalization: Predictors of Pro-Drug Decriminalization Attitudes in Canada. J. Drug Issues 2022, 52, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsenko, V.; Kogan, M.; Konstantinov, V.; Marinova, T.; Reznik, A.; Isralowitz, R. Religion in Russia: Its impact on university student medical cannabis attitudes and beliefs. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 54, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findley, P.A.; Edelstein, O.E.; Pruginin, I.; Reznik, A.; Milano, N.; Isralowitz, R. Attitudes and beliefs about medical cannabis among social work students: Cross-national comparison. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 58, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamenka, N.; Pikirenia, U. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about medical cannabis among the medical students of the Belarus State Medical University. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 57, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, E.; Gunter, J.; Tanner, E. Ohio physician attitudes toward medical Cannabis and Ohio’s medical marijuana program. J. Cannabis Res. 2020, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Gritsenko, V.; Bonnici, J.S.; Marinova, T.; Reznik, A.; Isralowitz, R. Psychology Student Attitudes and Beliefs toward Cannabis for Mental Health Purposes: A Cross National Comparison. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 1866–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, O.E.; Wacht, O.; Grinstein-Cohen, O.; Reznik, A.; Pruginin, I.; Isralowitz, R. Does religiosity matter? University student attitudes and beliefs toward medical cannabis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 51, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, O.E. Attitudes and beliefs of medicine and social work students about medical cannabis use for epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022, 127, 108522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resko, S.; Ellis, J.; Early, T.J.; Szechy, K.A.; Rodriguez, B.; Agius, E. Understanding Public Attitudes toward Cannabis Legalization: Qualitative Findings from a Statewide Survey. Subst. Use Misuse 2019, 54, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnici, J.; Clark, M. Maltese health and social wellbeing student knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about medical cannabis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 60, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.A. Beliefs about cannabis at the time of legalization in Canada: Results from a general population survey. Harm Reduct. J. 2020, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotov, Y.; Grinstein Cohen, O.; Findley, P.A.; Reznik, A.; Isralowitz, R.; Willard, S. Attitudes and knowledge about medical cannabis among Israeli and American nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 99, 104789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, D.; Collins, C.; Delargy, I.; Laird, E.; van Hout, M.C. Irish general practitioner attitudes toward decriminalisation and medical use of cannabis: Results from a national survey. Harm Reduct. J. 2017, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, J.R.; Forrest, B.D.; Freeman, R.A. Medical marijuana patient counseling points for health care professionals based on trends in the medical uses, efficacy, and adverse effects of cannabis-based pharmaceutical drugs. Res. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 2016, 12, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimrigk, S.; Marziniak, M.; Neubauer, C.; Kugler, E.M.; Werner, G.; Abramov-Sommariva, D. Dronabinol Is a Safe Long-Term Treatment Option for Neuropathic Pain Patients. Eur. Neurol. 2017, 78, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, K.; Weinstein, A.M. Synthetic and Non-synthetic Cannabinoid Drugs and Their Adverse Effects—A Review from Public Health Prospective. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzhepakovsky, I.V.; Areshidze, D.A.; Avanesyan, S.S.; Grimm, W.D.; Filatova, N.V.; Kalinin, A.V.; Kochergin, S.G.; Kozlova, M.A.; Kurchenko, V.P.; Sizonenko, M.N.; et al. Phytochemical Characterization, Antioxidant Activity, and Cytotoxicity of Methanolic Leaf Extract of Chlorophytum Comosum (Green Type) (Thunb.) Jacq. Molecules 2022, 27, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, S.; MacDonald, T.; Romanick, M.; Jupp, J.; Wiernikowski, J.; Vennettilli, A.; Khanna, M.; Patel, P.; Ning, W.; Sung, L.; et al. Safety and efficacy of nabilone for acute chemotherapy-induced vomiting prophylaxis in pediatric patients: A multicenter, retrospective review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcott, J.G.; del Rocío Guillen Núñez, M.; Flores-Estrada, D.; Oñate-Ocaña, L.F.; Zatarain-Barrón, Z.L.; Barrón, F.; Arrieta, O. The effect of nabilone on appetite, nutritional status, and quality of life in lung cancer patients: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3029–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’hooghe, M.; Willekens, B.; Delvaux, V.; D’haeseleer, M.; Guillaume, D.; Laureys, G.; Nagels, G.; Vanderdonckt, P.; van Pesch, V.; Popescu, V. Sativex® (nabiximols) cannabinoid oromucosal spray in patients with resistant multiple sclerosis spasticity: The Belgian experience. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flachenecker, P.; Henze, T.; Zettl, U.K. Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of Nabiximols (Tetrahydrocannabinol/Cannabidiol Oromucosal Spray) in Clinical Practice. Eur. Neurol. 2014, 72, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrot, R.J.; Hubbard, J.R. Cannabinoids: Medical implications. Ann. Med. 2016, 48, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anciones, C.; Gil-Nagel, A. Adverse effects of cannabinoids. Epileptic Disord. 2020, 21, S29–S32. [Google Scholar]

- Pisanti, S.; Bifulco, M. Medical Cannabis: A plurimillennial history of an evergreen. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8342–8351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Kirchhof, M.G. Dermatology-Related Uses of Medical Cannabis Promoted by Dispensaries in Canada, Europe, and the United States. J. Cutan Med. Surg. 2019, 23, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheriff, T.; Lin, M.J.; Dubin, D.; Khorasani, H. The potential role of cannabinoids in dermatology. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 31, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budney, A.J.; Sargent, J.D.; Lee, D.C. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): Parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction 2015, 110, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiplo, S.; Asbridge, M.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Hammond, D. Medical cannabis use in Canada: Vapourization and modes of delivery. Harm Reduct. J. 2016, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Lippmann, S. Vaping medical marijuana. Postgrad. Med. 2018, 130, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.; Sirven, J.I. Historical perspective on the medical use of cannabis for epilepsy: Ancient times to the 1980s. Epilepsy Behav. 2017, 70, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, S.; Kumar, D.; Khan, M.T.; Giyanwani, P.R.; Kiran, F. Epilepsy and Cannabis: A Literature Review. Cureus 2018, 10, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.D.; Bober, S.L.; Mindra, S.; Moreau, J.M. Medical cannabis—The Canadian perspective. J. Pain Res. 2016, 9, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.I.; Ind, P.W. Effect of cannabis smoking on lung function and respiratory symptoms: A structured literature review. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2016, 26, 16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Hausman, J.-F.; Guerriero, G. Cannabis sativa: The Plant of the Thousand and One Molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felnhofer, A.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Stoll, A.; Klier, C. Knowledge about and attitudes towards medical cannabis among Austrian university students. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 58, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, A.K.; Barnes, A.J.; Cobb, C.O.; Nicksic, N.E. Attitudes about and correlates of cannabis legalization policy among U.S. young adults. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherburn, D.; Darke, S.; Zahra, E.; Farrell, M. Who would try (or use more) cannabis if it were legal? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022, 41, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, S.; Guo, Y.; Slaven, M.; Lalani, A.-K.; Shaw, E.; Tajzler, C.; Hotte, S.; Kapoor, A. The perceptions and beliefs of cannabis use among Canadian genitourinary cancer patients. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2022, 16, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanco, K.; Dumlao, D.; Kreis, R.; Nguyen, K.; Dibaj, S.; Liu, D.; Marupakula, V.; Shaikh, A.; Baile, W.; Bruera, E. Attitudes and Beliefs About Medical Usefulness and Legalization of Marijuana among Cancer Patients in a Legalized and a Nonlegalized State. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, O.E.; Wacht, O.; Isralowitz, R.; Reznik, A.; Bachner, Y.G. Beliefs and Attitudes of Graduate Gerontology Students about Medical Marijuana Use for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, V.; Reznik, A.; Zangeneh, M.; Gritsenko, V.; Khamenka, N.; Kalita, V.; Isralowitz, R. Foreign Medical Students in Eastern Europe: Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs About Medical Cannabis for Pain Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamenka, N.; Skuhareuski, A.; Reznik, A.; Isralowitz, R. Medical Cannabis Pain Benefit, Risk and Effectiveness Perceptions among Belarus Medical Students. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpot, L.M.; Ebbert, J.O.; Hurt, R.T. A survey of the attitudes, beliefs and knowledge about medical cannabis among primary care providers. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujcic, I.; Pavlovic, A.; Dubljanin, E.; Maksimovic, J.; Nikolic, A.; Sipetic-Grujicic, S. Attitudes toward Medical Cannabis Legalization among Serbian Medical Students. Subst. Use Misuse 2017, 52, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orjuela-Rojas, J.M.; García Orjuela, X.; Ocampo Serna, S. Medicinal cannabis: Knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of Colombian psychiatrists. J. Cannabis Res. 2021, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bega, D.; Simuni, T.; Okun, M.S.; Chen, X.; Schmidt, P. Medicinal Cannabis for Parkinson’s Disease: Practices, Beliefs, and Attitudes among Providers at National Parkinson Foundation Centers of Excellence. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2017, 4, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clobes, T.A.; Palmier, L.A.; Gagnon, M.; Klaiman, C.; Arellano, M. The impact of education on attitudes toward medical cannabis. PEC Innov. 2022, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokratous, S.; Mpouzika, M.D.A.; Kaikoushi, K.; Hatzimilidonis, L.; Koutroubas, V.S.; Karanikola, M.N.K. Medical cannabis attitudes, beliefs and knowledge among Greek-Cypriot University nursing students. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 58, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulou, M.; Vouzavali, F.; Paikopoulou, D.; Paschali, A.; Mpouzika, M.D.A.; Karanikola, M.N.K. Attitudes, beliefs and knowledge towards Medical Cannabis of Greek undergraduate and postgraduate university nursing students. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 58, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiki, G.; Richa, S.; Kazour, F. Medical and recreational cannabis: A cross-sectional survey assessing a sample of physicians’ attitudes, knowledge and experience in a university hospital in Lebanon. L’Encephale 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, G.L.; Njai, R.; Grant, A.M. Clinician Beliefs and Practices Related to Cannabis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022, 7, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Smetana, S.; Hossaini, S.M.; Heinz, V.; Kircher, C. The Impact of Corona Pandemic on Consumer’s Food Consumption. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2021, 16, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Mehdizadeh, Z.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Kazemi, S.; Choudhury, A.R.; Tampubolon, K.; Mehdizadeh, M. Chemical Strategy for Weed Management in Sugar Beet. Sugar Beet Cultiv. Manag. Process. 2022, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Zannou, O.; Karim, I.; Kasmiati; Awad, N.M.H.; Gołaszewski, J.; Heinz, V.; Smetana, S. Avoiding Food Neophobia and Increasing Consumer Acceptance of New Food Trends—A Decade of Research. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Country | Status (Legal/Illegal) | Medical/Recreational | Possession Limit | Reason for Legalization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uruguay | Completely Legal | Both | up to 40 g/month or 10 g/week | 1. Reduce crime rate 2. Reduce illegal trading | [13,14] |

| 2 | Canada | Completely Legal | Both | legal cannabis up to 30 g | 1. Reduce the risk of its consumption in youth and children (Age ≤ 18 years) 2. Public health protection from potential risk 3. Increase workplace, road and public places safety by addressing impairment 4. Restrict illegal market | [15,16] |

| 3 | Malta | Completely Legal | Both | dried cannabis up to 50 g | 1. Decriminalization for responsible use 2. Fight back illicit drug trafficking 3. Nullify the criminal records of people in illicit possession of substance | [17] |

| 4 | Netherlands | Completely Legal | Both | not more than 5 g | 1. Combat drug-related crime and nuisance | [18] |

| 5 | United States of America | Partially Legal (in 19 states) | Both | varying amounts between 10 g to 30 g | 1. Alleviate the pain of critically ill people 2. Complete potential and shortcomings are not clear yet 3. Overcome the issue of illicit market | [19,20] |

| 6 | Australia | Partially Legal (Australian Capital Territory) | Both | up to 50 g | 1. Availability of drug to treat serious patients 2. Black market uncertified product without the guarantee 3. Associated criminality 4. Flexible customs regulations to leverage the research on therapeutic benefit | [21,22] |

| 7 | Spain | Partially Legal | Medical (legal)/ Recreational (decriminalized) | no limit | 1. Legalized with no upper limit on possession unless the consumer is a menace to the society | [23] |

| 8 | Portugal | Partially Legal | Medical (legal)/ Recreational (decriminalized) | Not reported | 1. Medical use (in form of Sativex) to relieve pain associated with epilepsy, MS and oncology | [24] |

| 9 | South Africa | Legal in private and illegal in public | Both | up to 600 g in private and up to 60 g in public | 1. The government legalized cannabis owing to fragile health and law system, unemployment. 2. Moreover, the conducive environment would have propelled illegal cultivation of cannabis | [25] |

| 10 | Paraguay | Partially Legal | Both | maximum of 10 g | 1. Curb the illicit drug trade 2. Open new avenues for revenue generation as the country exports cannabis at cheap rates | [26] |

| Formulation/Form | FDA Approval | Major Constituents | Mode of Administration | Medical Use/Benefits/Ailment Treatment | Efficacy | Adverse Effects | Patient Response | Remarks/Recommendation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dronabinol | Yes | Synthetic analog of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | Oral ingestion | Improving sleep, weight gain in cancer and HIV/AIDS patients, mitigating chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), and neuropathic pain associated with multiple sclerosis (MS) and chronic non-cancer pain patients, glaucoma. | Few conflicting studies on use of dronabinol in weight gain, progression of progressive MS and glaucoma have been found. | Dizziness and drowsiness (the most common adverse effects), CNS related effects, euphoria, sedation, confusion, feeling intoxicated, dysphoria, paranoia, hallucinations, and arterial hypotension and postural hypotension (reported in few abstracts). | Regarded as safe long term treatment option for anorexia induced by HIV/AIDS. | Adverse effects are dose dependent and resolve after the discontinuation. However, counselling should be imparted to patients to educate them on withdrawal symptoms (anxiety, irritability, restlessness and sleep disturbances) which subside within twelve weeks after cessation. | [76,77] |

| Nabilone | Yes | Synthetic analog of Δ9-THC with a high bioavailability ≥60% | Oral ingestion | Improving sleep, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis associated pain, and spasticity in MS and Alzheimer’s disease. | Efficacious for all the stated medical uses. | Euphoria, sedation, dizziness, tachycardia, chest pain, and muscle twitches. | Lung cancer patients under naboline treatment exhibited improved social and emotional functioning, reduced pain and insomnia as compared to control group. | Potential improvement in nutritional status in experimental group has been observed, but larger sample population needs to be taken into account to draw robust conclusion. | [78,79,80,81] |

| Nabiximol | Yes | Synthetic analog of Δ9-THC with a high bioavailability ≥60% | Oromucosal spray | Spasticity in MS patients and associated neuropathic pain and chronic pain in non-cancer patients. | Long term tolerability and effectiveness against MS spasticity was observed in clinical practice. | Physiological effects, cardiovascular effects, pulmonary effects and central nervous system (CNS) effects. | Majority of patients reported relief and effectiveness after 12 weeks of treatment. | NA | [76,82,83,84] |

| Medical cannabis/Marijuana | NA | THC and/or cannabidiol (CBD) | Smoked marijuana | Crohn’s disease, neuropathic pain, associated with chronic non-cancer pain and post-operative pain, and glaucoma. | Efficacious in all stated medical conditions except for managing symptoms of Crohn’s disease and for the treatment of glaucoma. | Dizziness, drowsiness, increased trend in CNS, cardiovascular and respiratory effects. | NA | Not advisable to drive under the influence of medical or recreational cannabis owing to CNS effects which may lead to fatal road accidents. | [76,85] |

| Orally ingested marijuana | Bladder control in MS patients, neuropathic pain in chronic non-cancer pain patients, and improving sleep. Reduces opiate dependence. | Not efficacious against neuropathic pain, postoperative pain, and efficacy was unable to be determined for its use in Tourette’s syndrome and glaucoma. | Adverse effects associated with known side effects of cannabinoids (fatigue, convulsion, lethargy). | NA | NA | [76,86] | |||

| Topical application | Dermatological treatments for psoriasis, lupus, nail-patella syndrome. Preliminary studies support its use in pruritus, acne, dermatitis, wound healing and skin cancer. | NA | Cannabis allergy (analphylaxis) manifesting as urticaria and pruritus, necrosis and ulcers. Further periorbital erythema and edema can be triggered by airborne cannabis allergens. | NA | NA | [87,88] | |||

| Cannabis | NA | High cannabidiol content | Vaporization | Osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. | Effective and also avoids inhalation of smoke, carbon monoxide, ash, ammonia, hydrogen cyanide, and tar (i.e., phenols and carcinogens such as benzanthracene and benzopyrene). | Long term use may result in attitude and cognitive effects especially posing pronounced risk to young adults and children. Addiction or problematic use attributed to positive advertisement of vaping. | In Arizona-based study, 63% of patients with arthritis, 77% of fibromyalgia patients, and 51% of patients suffering from neuropathic pain reported overall pain relief. | Vaporizer is the preferred mode which reduces the harm linked with smoking but the high cost may discourage its widespread use. Therefore, the device should be available at affordable price. | [89,90,91] |

| Oral | Epilepsy | NA | Somnolence, decreased appetite, diarrhea, fatigue and increased convulsions. | 42% of the sample size reported a reduction of more than 80% in seizure frequency, whereas 32% reported a reduction of 25 to 60% in seizure frequency. | Antiepileptic agent in animal model, limited scientific study for evidence to treat epilepsy in humans is available. | [92,93] | |||

| Cannabis/cannabis extract | NA | Not reported | Sublingual administration | To ameliorate the unpleasant sensation of breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) patients. | NA | Exacerbates psychiatric disturbances, immunosuppression, cardiac disease, respiratory disease, and obesity. | NA | Onset of action and bioavailability may be faster and higher for this route compared with oral administration. | [94] |

| Smoking | Various types of pain relief | Quick relief due to immediate deposition of active ingredients in the blood stream after absorption via mucous membrane of the lungs. | Habitual cannabis smokers showed alterations in tracheobronchial mucosa and develop acute bronchitis. | Marijuana smoke contains 50–70% more carcinogenic ingredients than cigarette smoke that can lead to lung cancer and thus may worsen chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma and impair intrauterine growth in pregnancy and cause structural and neurobehavioral defects in the fetus. | Health risks outweigh the benefits and hence not recommended for pregnant and lactating women. | [95,96] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siddiqui, S.A.; Singh, P.; Khan, S.; Fernando, I.; Baklanov, I.S.; Ambartsumov, T.G.; Ibrahim, S.A. Cultural, Social and Psychological Factors of the Conservative Consumer towards Legal Cannabis Use—A Review since 2013. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710993

Siddiqui SA, Singh P, Khan S, Fernando I, Baklanov IS, Ambartsumov TG, Ibrahim SA. Cultural, Social and Psychological Factors of the Conservative Consumer towards Legal Cannabis Use—A Review since 2013. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710993

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiddiqui, Shahida Anusha, Prachi Singh, Sipper Khan, Ito Fernando, Igor Spartakovich Baklanov, Tigran Garrievich Ambartsumov, and Salam A. Ibrahim. 2022. "Cultural, Social and Psychological Factors of the Conservative Consumer towards Legal Cannabis Use—A Review since 2013" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710993

APA StyleSiddiqui, S. A., Singh, P., Khan, S., Fernando, I., Baklanov, I. S., Ambartsumov, T. G., & Ibrahim, S. A. (2022). Cultural, Social and Psychological Factors of the Conservative Consumer towards Legal Cannabis Use—A Review since 2013. Sustainability, 14(17), 10993. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710993