Urban Community Resilience Amidst the Spreading of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Rapid Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

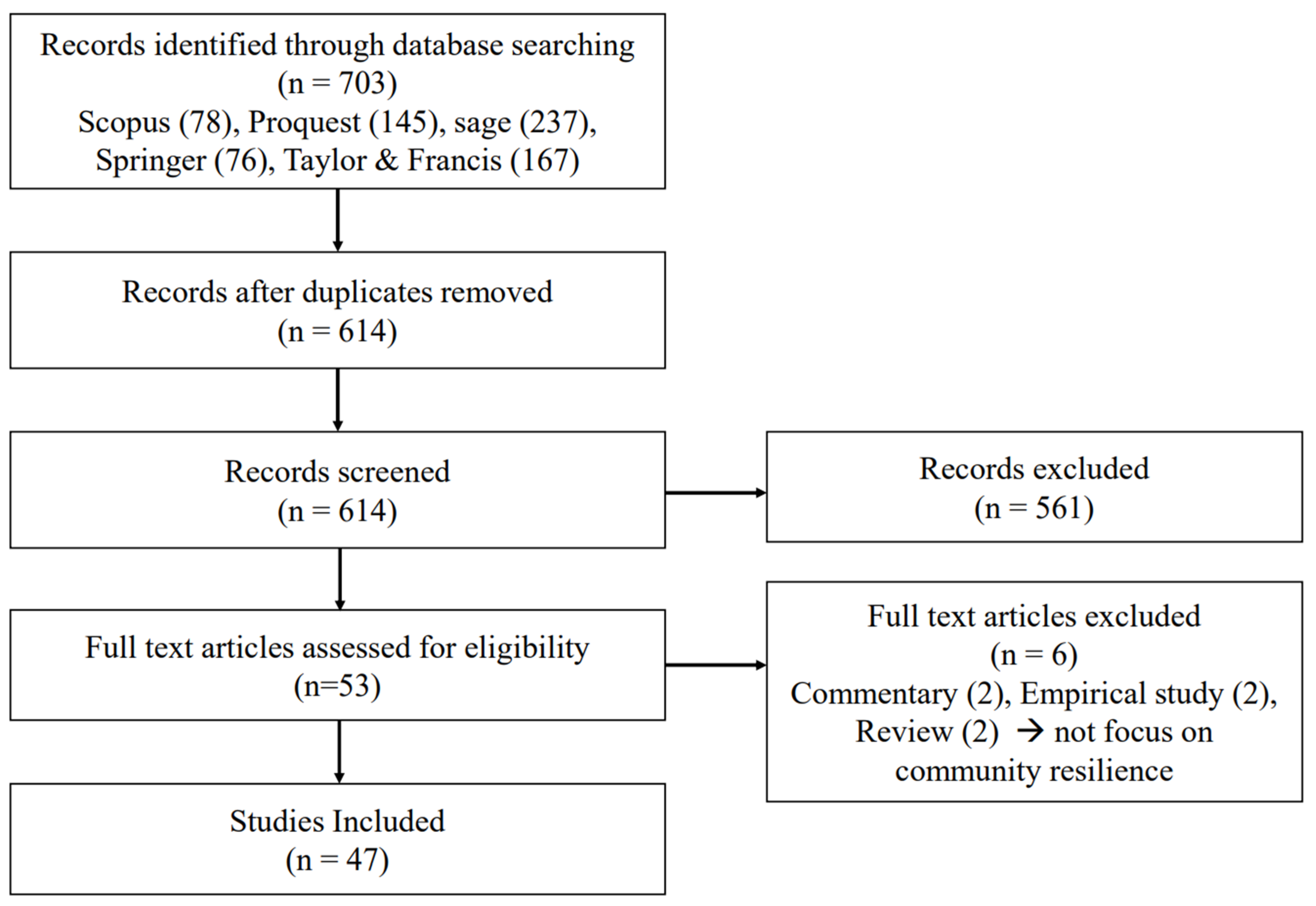

2. Method

- The inclusion criteria for finding publications are:

- (1)

- Paper regarding cities/urban and community resilience during pandemics and other shock/disaster from any country (including vulnerability, capacity, adaptation, responses to the COVID-19)

- (2)

- Written in English

- (3)

- Published from 2019 to 2021 when the COVID-19 pandemic affected society

- (4)

- Literature in observational commentaries, frameworks, conceptual models, literature reviews, and empirical evidence was included in this review.

- The exclusion criteria of those excluded from this review:

- (1)

- Emphasize the articles are different from community resilience.

- (2)

- The study focus is other than the urban community.

- (3)

- The articles discussed the impacts of COVID-19 with unverified adaptation, concrete solutions, or research gaps.

3. Results

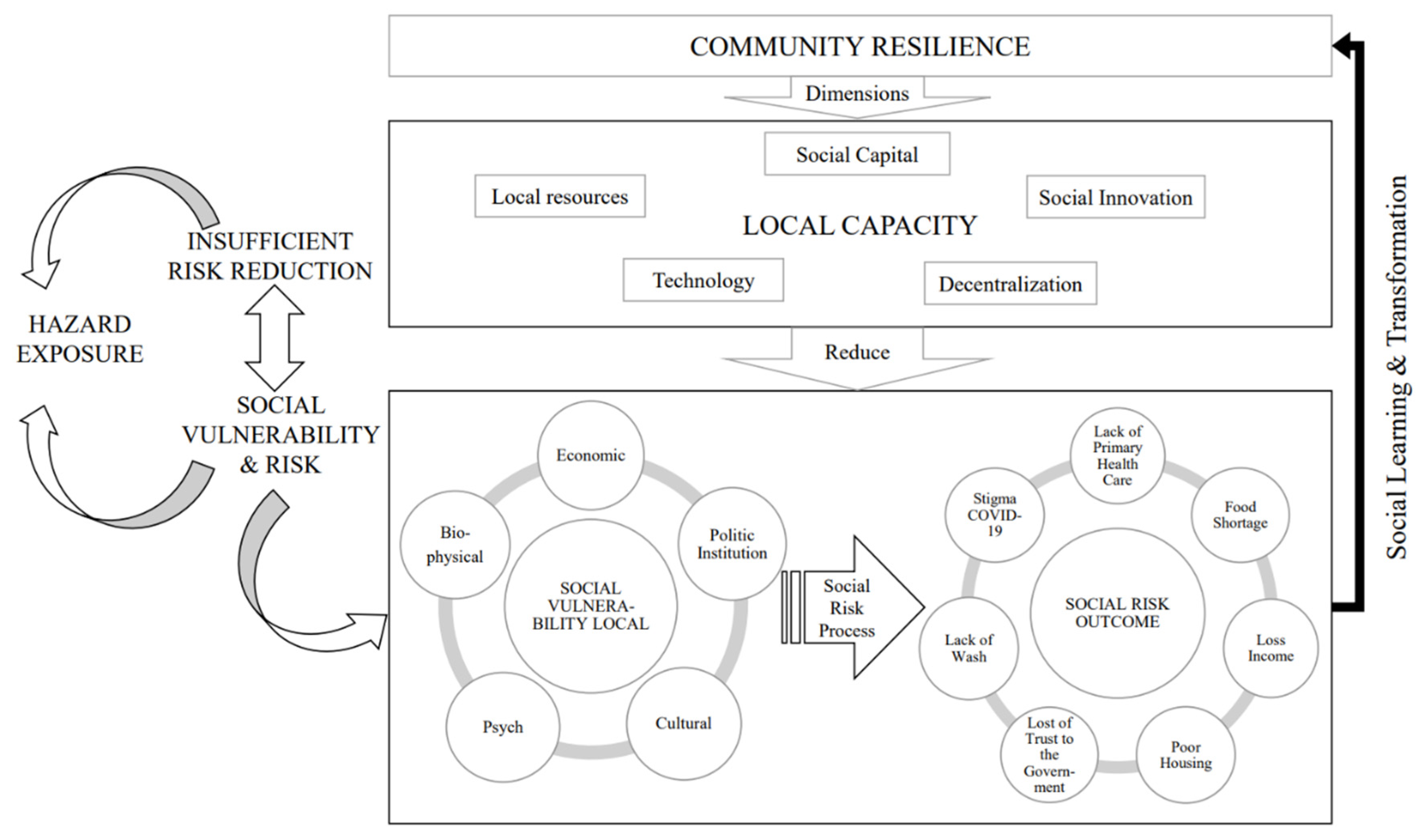

3.1. Urban Community Vulnerable to the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.2. Initiative Community Organization

3.3. Key Dimensions in Building Community Resilience amid COVID-19 Pandemic

3.3.1. Social Capital

3.3.2. Social Innovation

3.3.3. Local Resource and Decentralization

3.3.4. Technology and Capacity Building

4. Conclusions

5. Further Research Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. COVID-19 in an Urban World. In United Nation: Policy Brief; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, T.G.; Frantz, R.Z.; Frizzo, M.N.; François, C.H.R.; Ludwig, M.S.; Mesenburg, M.A.; Buratti, G.P.; Franz, L.B.B.; Berlezi, E.M. Insufficient social distancing may contribute to COVID-19 outbreak: The case of Ijuícity in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Seth, P.; Tiwary, H. How does COVID-19 aggravate the multidimensional vulnerability of slums in India? A Commentary. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2020, 2, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boza-Kiss, B.; Pachauri, S.; Zimm, C. Deprivations and Inequities in Cities Viewed through a Pandemic Lens. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 645914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Chowdhury, F.J.; Rahman, M.M. COVID-19 Pandemic: Rethinking Strategies for Resilient Urban Design, Perceptions, and Planning. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 668263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaja, T.; Kusyati, N.; Fukushi, K. Community Resilience and Empowerment through Urban Farming Initiative as Emergency Response. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 799, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombroski, K.; Diprose, G.; Sharp, E.; Graham, R.; Lee, L.; Scobie, M.; Richardson, S.; Watkins, A.; Martin-neuninger, R. Food for People in Place: Reimagining Resilient Food Systems for Economic Recovery. Sustainability 2021, 12, 9369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M. Strategic decisions on urban built environment to pandemics in Turkey: Lessons from COVID-19. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonge, O.; Sonkarlay, S.; Gwaikolo, W.; Fahim, C.; Cooper, J.L.; Peters, D.H. Understanding the role of community resilience in addressing the Ebola virus disease epidemic in Liberia: A qualitative study (community resilience in Liberia). Glob. Health Action 2019, 12, 1662682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Cutuli, J.J.; Herbers, J.E.; Reed, M.-G.J. Resilience in Development. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeland, B.; Carlson, E.; Sroufe, L.A. Resilience as process. Dev. Psychopathol. 1993, 5, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Strengthening Family Resilience, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. Conceptualizing community resilience and the social dimensions of risk to overcome barriers to disaster risk reduction and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Trejos, B.; Qin, H.; Joo, D.; Debner, S. Conceptualizing community resilience: Revisiting conceptual distinctions. Community Dev. 2017, 48, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Liao, L.; Li, H.; Su, Z. Which urban communities are susceptible to COVID-19? An empirical study through the lens of community resilience. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, J.; Peralta, D.O.; Vanelli, F.; Edelenbos, J.; Olvera, B.C. The emergence of Urban Community Resilience Initiatives during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Exploratory Study. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2022, 34, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, R.L.; Mah, S.M.; Howell, N.; Larsen, M.M. Social Cohesion and Community Resilience During COVID-19 and Pandemics: A Rapid Scoping Review to Inform the United Nations Research Roadmap for COVID-19 Recovery. Int. J. Health Serv. 2021, 51, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Rhinology 2020, 20, 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new Resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eachus, P. Community Resilience: Is it Greater than the Sum of the Parts of Individual Resilience? Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 18, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, S.; Eshel, Y.; Lahad, M.; Leykin, D. National Resilience: A New Self-Report Assessment Scale. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogiannis, T. A qualitative model of patterns of resilience and vulnerability in responding to a pandemic outbreak with system dynamics. Saf. Sci. 2021, 134, 105077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, V.; de Foo, C.; Abdalla, S.M.; Jung, A.S.; Tan, M.; Wu, S.; Chua, A.; Verma, M.; Shrestha, P.; Singh, S.; et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from 28 countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridde, V.; Gautier, L.; Dagenais, C.; Chabrol, F.; Hou, R.; Bonnet, E.; David, P.M.; Cloos, P.; Duhoux, A.; Lucet, J.-C.; et al. Learning from public health and hospital resilience to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Protocol for a multiple case study (Brazil, Canada, China, France, Japan, and Mali). Health Res. Policy Syst. 2021, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, G.P.; Haines, A. Asset Building and Community Development; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ife, J. Human Right from Below, Achieving Right through Community Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M.G.; Lappin, B.W. Community Organization: Theory, Principles, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Harper and Row Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, D.J. Community Susceptibility and Resiliency to COVID-19 Across the Rural-Urban Continuum in the United States. J. Rural. Health 2020, 36, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conteh, A.; Kamara, M.S.; Saidu, S.; Macarthy, J.M. COVID-19 Response and Protracted Exclusion of Informal Settlement Residents in Freetown, Sierra Leone. IDS Bull. 2021, 52, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, I.D.; Ortiz, C.; Samper, J.; Millan, G. Mapping repertoires of collective action facing the COVID-19 pandemic in informal settlements in Latin American cities. Environ. Urban. 2020, 32, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.; Gilbert, L. South African Jewish Responses to COVID-19. Contemp. Jew. 2021, 41, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maudrie, T.L.; Lessard, K.H.; Dickerson, J.; Aulandez, K.M.W.; Barlow, A.; O’Keefe, V.M. Our Collective Needs and Strengths: Urban AI/ANs and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perspective 2021, 6, 611775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitman, Y.; Yeshua-katz, D. WhatsApp group as a shared resource for coping with political violence: The case of mothers living in an ongoing conflict area. Mob. Media Commun. 2022, 10, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, N.; Mela, S.; Pede, E. A resilient response to the social-economic implications of coronavirus. The case of Snodi Solidali in Turin. Urban Res. Pract. 2020, 13, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, O.; Mahagna, A.; Shamia, A.; Slobodin, O. Health-care services as a platform for building community resilience among minority communities: An Israeli pilot study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, M.; Meeker, J.; MacGregor, H.; Schmidt-Sane, M.; Wilkinson, A. COVID-19: Key Considerations for a Public Health Response; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kimani, J.; Steege, R.; Makau, J.; Nyambuga, K.; Wairutu, J.; Tolhurst, R. Building forward better: Inclusive livelihood support in nairobi’s informal settlements. IDS Bull. 2021, 52, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszczyk, H.A.; Rahman, M.F.; Bracken, L.J.; Sudha, S. Contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on food security in two small cities in Bangladesh. Environ. Urban. 2020, 33, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejia, A.; Bhattacharya, M.; Miraglia, J. Community gardening as a way to build cross-cultural community resilience in intersectionally diverse gardeners: Community-based participatory research and campus-community-partnered proposal. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e21218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Systematic_Reviews2017_0.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.-J.; Tu, W.-X.; Wang, X.-C.; Shi, G.-Q.; Yin, Z.-D.; Su, H.-J.; Shen, T.; Zhang, D.-P.; Li, J.-D.; Lv, S.; et al. A practical community-based response strategy to interrupt Ebola transmission in sierra Leone, 2014–2015. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2016, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Questa, K.; Das, M.; King, R.; Everitt, M.; Rassi, C.; Cartwright, C.; Ferdous, T.; Barua, D.; Putnis, N.; Snell, A.C.; et al. Community engagement interventions for communicable disease control in low- and lower- middle-income countries: Evidence from a review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, B.T.T.; Quang, L.N.; Thanh, P.W.; Duc, D.M.; Mirzoev, T.; Bui, T.M.A. Community engagement in the prevention and control of COVID-19: Insights from Vietnam. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqer, M.H.; Al-Mudhaffer, A.F.; Kadhum, G.I. An analysis on capacities of old fabric in social resilience of city against COVID-19 epidemic: A case study of old fabric of Najaf Ashraf city. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2021, 16, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Scherer, D.; Chiu, Y.; Ofosu, N.N.; Luig, T.; Hunter, K.H.; Jabbour, B.; Farooq, S.; Mahdi, A.; Gayawira, A.; Awasis, F.; et al. Illuminating and mitigating the evolving impacts of COVID-19 on ethnocultural communities: A participatory action mixed—Methods study. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2021, 193, E1203–E1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Miao, X.; Lu, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, X. The Emergence of a COVID-19 Related Social Capital: The Case of China. Int. J. Sociol. 2020, 50, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.M.; Speers, M.A.; McLeroy, K.; Fawcett, S.; Kegler, M.; Parker, E.; Smith, S.R.; Sterling, T.D.; Wallerstein, N. Identifying and Defining the Dimensions of Community Capacity to Provide a Basis for Measurement. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hestad, D.; Tàbara, J.D.; Thornton, T.F. The role of sustainability-oriented hybrid organisations in the development of transformative capacities: The case of Barcelona. Cities 2021, 119, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.M. Building trust, resilient regions, and educational narratives: Municipalities dealing with COVID-19 in border regions of Portugal. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 20, 636–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mngumi, L.E. Exploring the contribution of social capital in building resilience for climate change effects in peri-urban areas, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 2671–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijster, T.; de Tullio, M.F. Commoning against the Corona Crisis. Law Cult. Humanit. ahead of print. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L.; van Blerk, L. Responding to COVID-19 in South Africa—Social solidarity and social assistance social assistance. Child. Geogr. 2021, 20, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.E. Community during the Pandemic and Civil Unrest. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2020, 4, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Betancur, J.C.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Pericàs, J.M.; Benach, J. Coronavirus disease 2019 and slums in the Global South: Lessons from Medellín (Colombia). Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 28, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmage, C.A.; Annear, C.; Equinozzi, K.; Flowers, K.; Hammett, G.; Jackson, A.; Kingery, J.N.; Lewis, R.; Makker, K.; Platt, A.; et al. Rapid Community Innovation: A Small Urban Liberal Arts Community Response to COVID-19. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2020, 4, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.; Gutschow, B.; Ragavan, M.I.; Ho, K.; Massart, M.; Ripper, L.; Muthama, V.; Miller, E.; Bey, J.; Abernathy, R.P. A Community Partnered Approach to Promoting COVID-19 Vaccine Equity. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 758–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Ahmed, N.; Pissarides, C.; Stiglitz, J. Comment Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokland, T.; Savage, M. Networked Urbanism: Social Capital in the City; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moralli, M.; Allegrini, G. Crises redefined: Towards new spaces for social innovation in inner areas? Eur. Soc. 2021, 23 (Suppl. 1), S831–S843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. Barriers to Enhancing Disaster Risk Reduction and Community Resilience: Evidence from the L’Aquila Disaster. Politics 2020, 8, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.F.; Filho, E.R.; Mendonca, R.M.L.O.; de Oliveira, L.G.R.; Pereira, H.G.G. Design for resilience: Mapping the needs of Brazilian communities to tackle COVID-19 challenges. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2020, 13, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T. Emotion governance and practice resilience in the reflexive modernity: How community social workers in a low-risk Chinese city work with people from Wuhan. Qual. Soc. Work 2021, 20, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Ali, H.; Bedford, J.; Boonyabancha, S.; Connolly, C.; Conteh, A.; Dean, L.; Decorte, F.; Dercon, B.; Dias, S.; et al. Local response in health emergencies: Key considerations for addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in informal urban settlements. Environ. Urban. 2020, 32, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osafo, E. Engaging Communities in Challenging Times: Lessons Learned from the Master Gardener Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2021, 23, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, S.P. COVID-19, the WHO Ottawa charter and the Red Cross-Red Crescent Movement. In Global Social Policy; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 20, pp. 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasy, K.; Gonzalez, L.R. Exploring Changes in Perceptions and Practices of Sustainability in ESD Communities in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, J. How are Tokyo’s independent restauranteurs surviving the pandemic? Asia-Pasific J. Jpn. Focus 2020, 18, 5483. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, B. Grid Governance in China’s Urban Middle-class Neighbourhoods. China Q. 2019, 241, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, A.S.; Ali, N.A.; Feroz, R.; Akber, N.; Meghani, S.N. Exploring community perceptions, attitudes and practices regarding the COVID-19 pandemic in Karachi, Pakistan. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassankhani, M.; Alidadi, M.; Sharifi, A.; Azhdari, A. Smart City and Crisis Management: Lessons for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benini, J.; Manzini, E.; Parameswaran, L. Care Up-Close and Digital: A Designers’ Outlook on the Pandemic in Barcelona. Des. Cult. 2021, 13, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Akerkar, R. Modelling, Measuring, and Visualising Community Resilience: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vulnerability | Group People | Coping Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Primary health care | Minority groups in urban and suburban with the limited protection | solidarity among communities during Pandemic COVID-19 |

| Food shortage |

|

|

| Loss Income | People with low-paid in informal jobs | Stimulate the local economy |

| Poor housing | Insecure tenure, overcrowding, and the lack of adequate basic sanitation infrastructure | Subsidy for the rent cost and supply free water and electricity |

| Loss of trust in governance | Minority race | Increase emotional communication with the community and engage local and minority races in planning |

| Lack of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) | People in the informal settlement are not connected to the national water grid | Developed a strategy for enhancing fair distribution of water and preventing people from clustering in one area |

| Stigma of COVID-19 | The lack of messaging from the government to address misinformation in informal settlements | Collaboration among communities & visit home to promote information and identify symptomatic patients |

| Type Initiative Community | Target Community | Challenges | Opportunities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom-up informal pathway | Focus on emergencies to adapt to the hardships of the lockdown for low-income settlements, especially to meet basic needs, such as water sanitation and food. | Lack of government participation and small government funding. | High community engagement |

| Bottom-up formal pathway | For specific target groups or neighborhoods in area-based approach to provide basic needs, COVID-19 prevention, microfinance. | Lack of government participation and small government funding. | Financial support from the funding organization |

| Hierarchic initiatives | Initiated by a single external actor, such as universities, government, Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), and the private sector. | Low level of community bonding | Many resources available from external actors |

| Networked initiatives | Created by diverse stakeholders, triggered by food and income insecurity and weak health infrastructure. | Low level of community trust and community empowerment | Lots of funding and expertise resources are provided by the government and external actors |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ningrum, V.; Chotib; Subroto, A. Urban Community Resilience Amidst the Spreading of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Rapid Scoping Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710927

Ningrum V, Chotib, Subroto A. Urban Community Resilience Amidst the Spreading of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Rapid Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710927

Chicago/Turabian StyleNingrum, Vanda, Chotib, and Athor Subroto. 2022. "Urban Community Resilience Amidst the Spreading of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Rapid Scoping Review" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710927

APA StyleNingrum, V., Chotib, & Subroto, A. (2022). Urban Community Resilience Amidst the Spreading of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Rapid Scoping Review. Sustainability, 14(17), 10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710927