Abstract

Teachers’ emotions and professional identities in response to educational reforms play a key role in teacher development and policy implementation. However, little attention has been paid to the shifting emotions of teachers of LOTEs (languages other than English). Taking a social-psychological approach, this study examines the emotional reactions and professional identities of LOTE teachers who were inspired to cater for the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. Semi-structured interviews and documentary analysis were used to probe the emotions and professional identities of 15 LOTE teachers in a Chinese foreign language university. The analysis identifies four categories of LOTE teachers’ identities: The enthusiastic accommodators, the lonely fighters, the drifting followers, and the passive executors. The findings indicate that current educational policies might lead to tensions among LOTE teachers without sufficient support, and suggest that the voices of LOTE teachers should be accommodated in the process of policy-making along with the affordances of support. The study reveals the necessity of adopting a social-psychological perspective on teacher development in the global multilingual educational context.

1. Introduction

Teachers’ professional identity has received significant attention in the field of teacher development since the 1980s [1]. Professional identity is generally viewed as a constellation of teachers’ opinions of how they regard themselves as teachers or their sense of self [2]. It also encompasses “social and policy expectations of what a good teacher is and the educational ideals of the teacher” [3] (p. 11).

Although teachers’ professional identity is influenced by a variety of factors [4], teacher emotion has been shown to be a key factor in the process of teacher identity construction and development [5,6]. Specifically, emotions contribute to teachers’ understanding of their professional lives [7], in that they are “the glue of identity” [8] (p. 336), which connect teachers’ thoughts, judgments, and beliefs, as well as giving meaning to their experiences [4]. Teachers’ emotions and professional identities are inextricably linked and affected by one another [6,9], and this close relationship tends to be particularly evident when faced with educational reforms [10,11]. Given that teachers’ voices, thoughts, and feelings are routinely neglected or marginalised during mandatory educational changes [12], teachers’ emotions in relation to educational reforms should be studied to explore teachers’ professional identities [4].

In terms of language teachers, existing research on their emotions and professional identity in response to educational reforms has mainly focused on English teachers [4,9,10], with little attention having been paid to the shifting emotions of teachers of LOTEs (languages other than English). Language teachers’ emotional responses to educational changes may help to both shape and reshape their professional identities and prompt or hinder the implementation of relevant policies [9]. Thus, a better understanding of LOTE teachers’ emotions can facilitate an understanding of changes in their professional identities during periods of educational reforms. Additionally, given the crucial role of language teachers in language education [13,14], their professional identities in and of themselves are worthy of exploration.

LOTE education in China has experienced rapid growth and become an important focus in recent years due to the promotion of the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative since 2013 [15,16], and this has led to significant demand for LOTE teachers. This initiative has brought a series of challenges for LOTE teachers’ professional development. For example, internally, LOTE teachers are trapped in anxiety and hesitation brought by the conflict between teaching and research; externally, they are burdened with heavy teaching loads for multiple courses with insufficient teaching resources, as well as diverse responsibilities for teaching, research, and administrative tasks, etc. [17]. Further, these challenges brought by the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative are more complex and greater than those brought by previous educational reforms, which mainly focus on teaching. However, little is known about LOTE teachers’ emotional responses to this and their professional identities in relation to it, both of which exert a vital influence on teachers’ professional development as well as LOTE education in general. Therefore, this paper aims to examine the emotions and professional identities of a cohort of LOTE teachers in China in response to educational reforms prompted by the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative.

2. A Social-Psychological Framework

This study employs a social-psychological perspective to explore LOTE teachers’ emotions and professional identities in response to the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. This approach emphasises “the interrelatedness of the individual and the social” [18] (p. 65). It regards emotions as the product of a dynamic interplay between individuals and the environment and allows us to examine identities in a wider context of ongoing reform [7,19,20,21]. Specifically, this approach enables a detailed investigation into how LOTE teachers appraise and emotionally respond to situational demands, and in this case, the educational policies introduced under the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative.

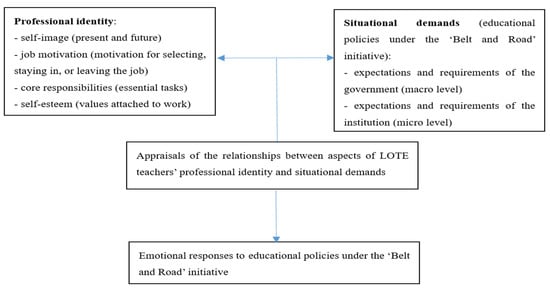

The analysis of their emotions will further enrich an understanding of teachers’ professional identities [7]. Generally, positive emotions are created by beneficial relationships between teachers’ professional identities and situational demands, while negative emotions are triggered by harmful relationships [19]. This study adopts an analytical framework adapted from a study by van Veen and Sleegers [7], which comprises four components: Professional identity, situational demands, appraisal process, and emotional responses (see Figure 1). LOTE teachers’ professional identity and situational demands are elaborated on in more detail in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Interactions between professional identity, situational demands, and emotional responses (adapted from [7]).

2.1. Professional Identity

Teachers’ professional identity may undergo drastic changes, or even be redefined completely [22]. For instance, previous research [11,21] has adopted the social-psychological approach to explore how teachers’ identity is influenced by educational reforms. Taking a social-psychological approach [7], this study focuses on certain elements of teachers’ professional identity that are closely associated with their perception of education reforms: Self-image, job motivation, core responsibilities, and self-esteem. Self-image is a descriptive element that indicates how teachers see themselves at present and in the future. Job motivation is a conative element of professional identity, consisting of the motives or drives that cause teachers to select their jobs, stay in the profession, or leave it. Core responsibilities illustrate what teachers view as essential tasks, involving teachers’ answers to questions such as “What tasks should I do to prove myself?” and “Why do I refuse to assume that task?” Self-esteem refers to what values teachers attach to their work, such as teaching, research, and social services. Understanding these different elements allows for deeper insights into teachers’ professional identity, and how they affect and are affected by situational demands [7].

2.2. Situational Demands: Educational Policies under the ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative

Van Veen and Sleegers [7] note that teachers are surrounded by other stakeholders who have their own ideas about how teachers should work, and different policy initiatives may influence teachers’ sense-making. The situational demands on LOTE teachers also include the expectations and requirements of the government (at the macro-level) and their institutions (at the micro-level).

2.2.1. Expectations and Requirements of the Government

Influenced by the implementation of the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative, many universities in mainland China have established LOTE-related programs [23]. China’s Ministry of Education has also enacted a series of educational policies related to LOTE teachers, including Guidelines for improving Languages Other than English (LOTE) programs and Schemes for promoting the construction of education on the ‘Belt and Road’.

The expectations and requirements of the government can be summarized and translated as follows:

- Improving teachers’ teaching abilities to promote LOTE talent cultivation.

- Strengthening country and area studies to serve the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative.

2.2.2. Expectations and Requirements of the Institution

This study selects University A, a university with a good reputation for foreign language education in China, as the context for micro situational demands. At this level, six main points are proposed:

- Mastering excellent language skills and receiving systematic language pedagogy training.

- Having experience of study or work abroad.

- Assuming responsibility for multiple courses and compiling textbooks that are oriented to the university’s characteristics.

- Publishing papers in CSSCI (China Social Sciences Citation Index) or SSCI (Social Sciences Citation Index) journals and getting funding for projects at provincial or ministerial levels.

- Actively engaging in social services (e.g., translation, research reports) to promote country and area studies.

- Assuming responsibility for knowledge of foreign affairs, student management, and foreign language website construction.

Situational demands on teachers exert influences on the four aspects of their professional identities through stress and stimulation, and teachers’ perceptions of situational demands and professional identities impact their emotional experiences. Moreover, positive emotions tend to reinforce teachers’ professional identities, and passive emotions are likely to undermine their professional identities [7]. Generally, the ongoing interaction between teachers’ professional identity and their situational demands results in complicated reforms for teachers and leads to a variety of emotions [7]. Therefore, guided by the social-psychological approach, this study attempts to answer the following research question:

What are the emotional reactions and professional identities of LOTE teachers in China to educational reforms under the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Participants

As one of the major foreign language universities in China, University A has established dozens of LOTE programs and actively undertaken tasks related to the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative to serve the government. For example, University A is committed to building a database to promote country and area studies, and it also encourages LOTE teachers to design original textbooks to improve LOTE talent cultivation. Therefore, the concerns of LOTE teachers in University A may contribute to a broader understanding of LOTE teachers.

The participants in the current study were 15 LOTE teachers from different majors in University A. They were recruited according to a purposive sampling procedure [24], based on a series of predefined features such as major, age, professional title, years of teaching, and degree level. First, we selected 15 different majors to recruit participants who were assistant lecturers or lecturers and under 50. Then, we tried to diversify the years of teaching of the participants. Finally, we examined their gender and degree to avoid homogeneity. The participants’ information is anonymously reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ profiles.

According to Table 1, the participants’ average age and years of teaching experience were 31 and 7, respectively, suggesting that the majority of the participants began working as teachers shortly after they had graduated with their Bachelor’s or Master’s degrees. Only 3 LOTE teachers had obtained a PhD degree, indicating that LOTE teachers might be inferior to their counterparts in English departments in terms of academic qualifications. More than 70 percent of the participants were female, who may face additional challenges related to professional title promotion and managing the burdens of family life (e.g., marriage, childcare). All participants were assistant lecturers or lecturers, who were more eager to achieve higher professional titles than their colleagues. All these factors may intensify the complexities of emotional experiences and professional identities of LOTE teachers who are managing the demands of the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative.

3.2. Data Collection

This paper employs a qualitative research approach to respond to the research question, using multiple data sources including semi-structured interviews and documentary analysis. To uncover teachers’ emotions in a more reliable way, semi-structured interviews were adopted as our main method to identify elements of teachers’ professional identity, and documentary analysis was utilised to further elaborate on situational demands. The first author had conducted interviews with the participants in previous studies, and the corresponding author and most of the participants were colleagues in University A several years ago. These conditions contributed to the smooth running of the interviews and the thorough expression of the participants’ genuine thoughts.

Information about the participants’ emotions emerged as they offered appraisals of the relationships between aspects of their professional identity and situational demands. Informed by the social-psychological framework, the interviews focused on three topics: (1) Participants’ perspectives on the situational demands they faced, (2) participants’ responses to these situational demands, and (3) how they viewed themselves and their work within the context of the situational demands. The main interview questions included: “What do you think about the research requirements of your university?” “How do you finish the task of writing research reports?” “What motivates you to stay in your profession?”, etc. (see Appendix A). The interviews were conducted in Mandarin and lasted approximately 50 min on average. Consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interviews, and the research aims, the nature of the work, and methods of data collection and use were all explained to each participant. The participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Documentary analysis was conducted on policy texts from both the government and University A. The former were formal documents retrieved from the official website of China’s Ministry of Education (see Section 2.2). Specifically, the latter mainly included (1) recruitment notices for LOTE teaching positions (2015–2021), (2) LOTE talent cultivation plans, (3) documents related to the evaluation of LOTE teachers’ current work and conditions for their professional title promotion, (4) documents related to support for LOTE teacher development, and (5) daily working notices of LOTE teachers.

3.3. Data Analysis

With participants’ informed consent, all the interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated into English for further analysis. All names were anonymised with pseudonyms during transcription. All researchers were involved in the transcription and translation process, including checking and discussing the translations to reach an agreement. All participants were also invited to check their own interview transcripts to enhance the reliability of the data. Next, thematic analysis [25] was employed to capture the participants’ professional identity elements (see Figure 1) and their perspectives on the situational demands they faced. This involved coding the transcripts and then allocating each code a meaningful name in order to develop themes inductively. The first cycle of coding involved the collection of interviewees’ original words relating to professional identity and situational demands, such as “I am only a translation tool” and “research requirements of the university are pushy”. Thereafter, these codes were compared and analysed, and any redundant ones were removed. Through the integration of similar initial codes, secondary codes were obtained, and these were further summarised and synthesised to complete the selective coding. The relationships between professional identity and situational demands were then analysed to elicit and interpret the participants’ emotions [7]. Ultimately, based on a constant comparison method [26], participants’ responses were compared and contrasted until final categories for professional identity and emotions were found. To improve the validity of the data, our interpretations were shared with the participants for checking. The participants agreed with our interpretations.

In the analysis of policy texts, researchers collaborated to extract relevant information related to LOTE teachers, carefully categorising the information in terms of macro and micro levels of situational demands (see Section 2.2). These policy texts were also used to verify the accounts of the participants. Here, it should be noted that this study does have some limitations, including small sample size and a lack of diachronic investigation of the participants. However, the data have helped to acquire a snapshot and explore the emotions and professional identities of LOTE teachers in a systematic and critical way.

4. Findings

The qualitative data revealed that more than two-thirds of the participants (11 interviewees) supported the situational demands, with divergent levels of support ranging from active participation to aimless participation (see Table 2). According to the characteristics of their emotional responses and professional identities, the LOTE teachers were categorized into four types: (1) The enthusiastic accommodators, (2) the lonely fighters, (3) the drifting followers, and (4) the passive executors. It should be noted that the study did not define these LOTE teachers in an exclusive way; indeed, some teachers may have belonged to two types concurrently. Within each type, we focused on four sub-themes: (1) LOTE teachers’ perspectives on situational demands, (2) their professional identities, (3) their emotional responses, and (4) their behavioural responses.

Table 2.

Emotional and behavioural responses of the participants.

4.1. The Enthusiastic Accommodators

Six teachers with MA degrees, who had worked in teaching for an average of 3 years, perceived situational demands as challenges and opportunities for their professional development. They were enthusiastic about the various demands and changes brought by the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative, and tried to meet the situational demands (T3, T8), defining themselves as “people who pursue comprehensive development”; this self-image meant that they were concerned with their holistic development, rather than only one aspect of it. For instance, T9, T12, and T13 spared no efforts to collect relevant materials and acquire experience or skills from their colleagues to design textbooks. They responded positively to the government’s demands for the improvement of LOTE teachers’ teaching ability and the promotion of LOTE talent cultivation [27,28]. T1 also attempted to improve her own research capabilities:

Even though I have no definite research areas, I will consult some professors to establish my research areas and improve my research capabilities as soon as possible.(T1)

The enthusiastic accommodators also attached importance to social services, such as translation and writing research reports. They worked to “serve the country, university, and students, as well as realize personal ambition” (T9, T12). Job motivations of these teachers seemed to involve moral considerations as well as value-laden choices; all six placed equal value on teaching, research, and social services, and regarded these tasks as their core responsibilities. These teachers also showed high-level self-esteem, tending to describe their profession using words such as “sacred”, “educational”, or “closely associated with national development”. Even the less interesting tasks, such as foreign language website construction and following foreign affairs, were seen as platforms to facilitate their personal development.

Additionally, they had a clear sense of their own future. One of their most important expectations was progress in research, echoing the fact that weak research capability and a lack of achievements are significant challenges for LOTE teacher development and LOTE education in China [29]:

We have prepared to cooperate with English teachers so as to publish academic papers in SSCI journals as soon as possible. We also hope we can get projects at provincial or ministerial level within three years.(T12, T13)

Overall, the four elements of the six teachers constituted their professional identity, namely, enthusiastic accommodators, who were filled with enthusiasm and aspiration and made active responses to situational demands. The professional identity and situational demands of enthusiastic accommodators were in a positive relationship, enabling positive emotional and behavioural responses [19]. In turn, these positive emotions and behaviours promoted their professional development and helped them to meet situational demands.

4.2. The Lonely Fighters

Two lecturers (T3, T8), both with MA degrees and teaching experience of an average of 5 years, were struggling to reach the requirements of University A in spite of discontented and even lonely professional lives. These two lonely fighters shared both similarities and differences with the enthusiastic accommodators. Similar to the enthusiastic accommodators, they acknowledged the significance of the situational demands, and passionately worked to improve themselves. They were fighters who never gave up no matter what they faced. T3, who had obtained his teaching position with only a Bachelor’s degree, was aware that his research capabilities were likely to be insufficient. Although he had published several academic papers, he was prepared to perfect his research:

It is really difficult to publish papers in SSCI or CSSCI journals. I have adopted various strategies to solve this problem, but it does not work! I still cannot reach the research requirements for being an associate professor. However, I will never give up.(T3)

Although T3 was determined to match the research-oriented requirement of University A, this fighter gradually developed feelings of loneliness due to the significant gap between his research engagement and his performance, as well as limited support from the university. Similarly, T8, the only teacher in her major, experienced significant pressure and loss during her struggle to submit research reports to the government on behalf of University A.

We often need to write relevant reports to serve the promotion of the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative and China’s participation in global governance. This is our moral duty, and also brings implications for our teaching and research. But with insufficient knowledge and experience, and nobody comes to help me, I often feel like I am ‘crossing a river by touching the stones’.(T8)

Consequently, ongoing interaction between their individual efforts, poor results and performance, and insufficient support from the university created a self-image of lonely fighters for these two teachers. They also regarded talent cultivation and the promotion of national development as core responsibilities.

Unlike the enthusiastic accommodators, the two lonely fighters aimed to realize personal ambitions, in particular to prove their own value. As T8 pointed out: “the outcome of research engagement and social services engagement reveals her capabilities, which motivated her to move forward in case she fell behind”. Complex perceptions and feelings emerged in relation to their current work, such as feeling “breathless but significant” or “exhausted but valuable”. T3 and T8 showed a firm belief in professional development and were determined to devote themselves to it, even though the process might be accompanied by personal feelings of loss and loneliness.

Gradually, T3 and T8 were shaped as lonely fighters who experienced passion, loss, and loneliness together, and actively embraced situational demands, in terms of their self-image, job motivation, core responsibilities, and self-esteem. To some extent, the lonely fighters may have been born from enthusiastic accommodators. Although their professional identity was consistent with the situational demands, complex and mixed emotions had developed over time related to their personal abilities and institutional support. However, their dedication to the profession seemed to be unaffected.

4.3. The Drifting Followers

Five lecturers (two with PhDs, three with MA qualifications), who had been working within the profession for 8 years on average, were classed as drifting followers. These teachers perceived situational demands merely as “national policy” and “institutional policy” and made no further effort to understand them. They did not care about the contents or values of these educational policies; they only “did what the policies said” in an indifferent way (T10, T11). They saw themselves as a “spare part”, “translational tool”, or a “working machine”.

In my university, I feel like a machine functioning all the time. I need to prepare for teaching, scientific research, and social services every day, and it seems impossible to stop. I cannot decide anything independently!(T4)

This situation was starker for female teachers. For example, T10 had to take care of her young son after work, even though she was always exhausted when she arrived home. Only after her son went to sleep could she then engage in research, leaving her little time to rest. Similarly, T11 saw herself as a translation tool, and other participants (T2, T6) noted that this image was also recognized by collaborators working in other disciplines. This suggests that LOTE teachers may not have their own research areas, which does not align with the government’s and University A’s concern for teachers’ research capabilities.

This group of teachers were obedient performers rather than designers of educational policies [4]. Given their enthusiasm and commitment to their work, they were able to stay in their profession under the current situational demands as well as being able to adapt to new ones. However, they did not have a clear idea as to what were their essential tasks, suggesting that they followed situational demands blindly without consideration of the value of each task assigned to them.

As for their prospects, these drifting followers felt they were unable to change their current situations characterized by burdensome tasks and duties, thus they had few expectations for their future progression.

I am tired of the boring and burdensome work, but I cannot change it. I also have no time to plan for the future. Particularly, I think I cannot easily achieve a position in universities any longer.(T10)

Given the fierce competition for jobs, these teachers agreed with T10, and they believed that they had to be tolerant of their university’s demands and felt helpless, which made the situation worse.

For these drifting followers, their professional identity was not consistent with their situational demands. Their self-image and self-esteem were in direct opposition to the situational demands and their job motivation conformed to the situational demands; however, they seemed to be uncertain about their core responsibilities. Consequently, the connection between their professional identity and their situational demands was so complex that they fell back on mere compliance, responding obediently and indifferently to current educational policies.

4.4. The Passive Executors

This category comprised four female lecturers, one with a PhD and three with MA degrees, who had worked for 16 years on average. These passive executors were doubtful about the situational demands, and specifically, were suspicious of those demands from the university. They thought the administrators of the university made unreasonable and idealistic expectations and demands. They presented a perception that LOTE teachers were expected to assume excessive responsibilities and duties, including teaching, research, and social services, as well as undertaking tasks such as foreign affairs and student management that English teachers did not have to (T14, T15). These burdensome tasks not only left them exhausted but also negatively impacted their work performance (T5, T7).

I am the only teacher in my department, I have to provide various kinds of courses, such as Reading, Writing, Literature and Translation. Therefore, I am always in class, or on my way to class.(T7)

In their teaching, they had to assume responsibility for multiple courses regardless of their educational experiences, driven by the shortage of LOTE teachers [16,30]. Although they perceived teaching as their core responsibility, the effectiveness and quality of their teaching could hardly be guaranteed under such conditions.

Despite an increasing emphasis on research and social services from the government and their university, teaching was still regarded as the most important motivation by some teachers (e.g., T14, T15). They were not happy that research and social services were receiving so much attention, and they perceived that this made little sense and only exacerbated their workload and pressure.

I doubt the reasonability of the research-oriented policy in my university. I am worried that the effect of teaching is influenced by great pressures brought by research, especially the professional title promotion. So I hate research, but I have to do it. How ridiculous it is!(T14)

In addition, it was a significant challenge for LOTE teachers to obtain research funding for a provincial or ministerial project within three years, as required by their university (T14). According to relevant institutional evaluation documents, teachers who failed in their assessment would have their allowance reduced and receive less support in terms of project applications and conference funds, ultimately influencing their professional title promotion.

Policy demands for universities to attach great importance to the assessment of teachers’ social services [31] exacerbated matters. In fact, some kinds of social services may not be directly associated with teaching or research, and LOTE teachers found themselves struggling to achieve the tasks allocated to University A by the government (e.g., T5, T7). These teachers expressed their hope that they would be able to focus on their teaching in the future, rather than research or social services, and not have to consider other redundant tasks they were asked to complete. For them, current educational policies did not take LOTE teachers’ characteristics into consideration, resulting in constraints on LOTE teacher development. Consequently, they paid lip service to the policies, and implemented them only passively.

These passive executors expressed more negative emotions than other groups. A negative relationship was evident between their professional identity and the situational demands, which was mainly embodied in conflicts related to the status of teaching, research, and social services, in terms of their job motivation and core responsibilities. Ultimately, this caused a series of negative emotions such as doubt, worry, and dissatisfaction.

5. Discussion

This study examined educational policies under the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative from the perspective of teachers, further deepening the understanding of the social-psychological approach to research on educational policies. As shown in the findings, the four types of LOTE teachers’ identities involved diverse and complex emotions. For example, the enthusiastic accommodators were full of enthusiasm and aspiration, while the lonely fighters experienced passion, loss, and loneliness. The findings also indicated the emergence of more negative emotions such as the indifference of the drifting followers and the doubt, worry, and even dissatisfaction of the passive executors. The emotions of the enthusiastic accommodators, the drifting followers, and the passive executors verify the rationale of the social-psychological approach [7]. Further, the complex emotions of the lonely fighters offer a new understanding of this approach; influenced by the interaction of personal factors and environmental factors [21], a positive relationship between teachers’ professional identity and their situational demands may nevertheless create negative emotions. In other words, the social-psychological approach in this study seems to overlook the influence of teachers’ capabilities and institutional support on their emotions.

The findings show that some demographic factors are related to LOTE teachers’ emotions. Similar to findings by Hargreaves [32], it was found that age and years of teaching tend to have a negative relationship with LOTE teachers’ emotional reactions to reforms. In this study, the average age of the four categories of LOTE teachers increased as more negative emotions emerged. The length of their average teaching experience showed a similar trend; early-career LOTE teachers are likely to be more enthusiastic and active than those in their later careers, a result that may be related to individual physical and mental conditions [32]. Other demographic factors, such as sex, qualification level, and professional title, did not exert a clear impact on LOTE teachers’ emotions, and it is therefore suggested that more personal factors (e.g., personal capabilities, age, years of teaching) and environmental factors (e.g., institutional support) should be included in social-psychological research to fully understand teacher emotions.

In general, this study further validates the close relationship between teachers’ professional identity and their emotions, which is in line with previous findings [6,9], especially in the context of educational reforms [4,11]. Although a longitudinal investigation of the participants’ professional identities in this study was not conducted, it may be predicted that their professional identities will evolve and be reshaped as time goes on or situational demands change [7,21]. For instance, T3 and T8 reported that they were originally enthusiastic accommodators but had become lonely fighters over time. Further exploration of the influence of situational demands on LOTE teachers’ professional identity is intended in future research.

This study has some implications for the promotion of LOTE teaching. Despite their diverse emotions and professional identities, all participants held the view that teaching is crucial. However, a shortage of LOTE teachers [16,30] and teaching resources (e.g., textbooks) were seen as significant obstacles to effective LOTE teaching. First, for university administrators, recruiting more LOTE teachers should be high on the agenda. This problem can be solved by creating special teaching positions that allow for a focus on LOTE teachers’ teaching capabilities rather than on their research capabilities. Cooperation with relevant universities to cultivate candidates for LOTE teaching would also be a good strategy. Second, LOTE teachers themselves should establish professional learning communities [33] or seek support from their universities to enable the exchange of teaching experiences and skills as well as teaching resources. For instance, utilising online courses as a teaching strategy may save LOTE teachers’ time in terms of lesson preparation, and communication with other teachers can be a source of inspiration for the compilation of textbooks.

In addition, the present study found that all the participants encountered significant stress when faced with situational demands, particularly the demands made by University A. This finding is in contrast with previous studies on English teachers’ emotional experiences during policy implementation [9,21], which may be related to the fact that the demands imposed on LOTE teachers are not matched by the support they receive from the university. In practice, LOTE teachers in this study seldom participated in the initial design of reforms [7] or made their own independent work-related decisions; rather, they acted merely as implementers of orders from higher levels (e.g., the Ministry of Education, administrators, experts). Clearly, this situation impedes LOTE teacher development and is consistent with previous studies, which found that teachers are expected to assume increasing responsibilities and roles but receive little attention and support [34]. This contradictory situation is rooted in the top-down mechanism for educational policy-making and implementation in China, as well as a technical-managerial perspective [35] that exerts a negative influence on teachers’ self-esteem because of poor autonomy and heavy accountability [7]. These two factors contribute to insufficient support for LOTE teachers, further influencing these teachers’ emotions and professional identities.

LOTE teachers are entitled to participate in educational policy-making, and their opinions as well as their feelings [7,9] should be considered during the process of policy-making and implementation. In particular, university administrators should develop a clear definition of the responsibilities and roles of LOTE teachers and provide sufficient support for their development.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has explored the emotional responses and professional identities of a group of Chinese LOTE teachers within the wider context of the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. Analysis of interview data and policy texts suggests that these LOTE teachers perceive tremendous pressure from current educational policies, experience diverse emotional responses, and construct different professional identities. Informed by the social-psychological framework, this study examines the interactions between professional identity, situational demands, and emotional responses, revealing the fact that LOTE teachers have to assume excessive tasks with insufficient support [36]. It is suggested that this problem results from the absence of LOTE teachers’ participation in educational policy-making, as well as the technical-managerial perspective adopted by the university, and argued more generally that LOTE teachers deserve more attention and support from their institutions.

This study has a number of limitations. Firstly, it was conducted with a group of LOTE teachers in a Chinese university, and the findings and implications may not be the same for LOTE teachers in other contexts. Secondly, longitudinal studies involving the same participants would be useful, and it could be helpful in making a comparison of LOTE teachers’ emotions and professional identities between different levels of universities so as to achieve a deeper understanding of the professional situation of LOTE teachers.

Despite these limitations, the study has provided insights into and implications for LOTE teacher development and educational policies under the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. On the one hand, university administrators should form more practical and reasonable expectations and requirements for LOTE teachers to relieve their stress. On the other hand, the voices of LOTE teachers should be appropriated into the process of educational policy-making, and more support should be provided by the government and institutions to help LOTE teachers develop positive emotions and identities. It is further suggested that future studies should focus on how to make positive use of the social-psychological perspective in terms of teacher development in the global multilingual educational context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and Q.S.; methodology, M.K. and Q.S.; software, M.K.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K., Q.S., and Y.Z.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.K. and Q.S.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, Q.S. and Y.Z.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, Q.S.; project administration, Q.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude goes to the LOTE teachers who took time out of their busy schedules to conduct the interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Interview questions.

Table A1.

Interview questions.

| 1 | What influences do you think the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative have on your professional development? |

| 2 | What’s your responses to these influences? How do you feel about them? |

| 3 | Can you share something about your teaching? |

| 4 | What do you think about the research requirements of your university? |

| 5 | How do you finish the task of writing research reports? How do you feel about it? |

| 6 | Can you describe your current professional image? Do you have any plan for your job in the future? |

| 7 | What motivates you to stay in your profession? |

| 8 | What are your essential tasks? |

| 9 | What’s the value of your profession? |

References

- Beijaard, D.; Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N. Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2004, 20, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nias, J. Primary Teachers Talking. A Study of Teaching as Work; Routledge: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Kington, A. Identity, well-being and effectiveness: The emotional contexts of teaching. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2008, 16, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.K.; Yin, H.B. Teachers’ emotions and professional identity in curriculum reform: A Chinese perspective. J. Educ. Chang. 2011, 12, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y. Emotions and language teacher identity: Conflicts, vulnerability, and transformation. TESOL Q. 2016, 50, 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Emotions and teacher identity: A poststructural perspective. Teach. Teach. 2003, 9, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, K.; Sleegers, P. Teachers’ emotions in a context of reforms: To a deeper understanding of teachers and reforms. In Advances in Teacher Emotion Research: The Impact on Teachers’ Lives; Schutz, P.A., Zembylas, M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, J.M.; Kahlbaugh, P. Emotion and identity. In Handbook of Emotions; Lewis, M., Haviland, J.M., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, USA, 1993; pp. 327–339. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, J.W.; Huang, J.; Teng, M.F. Identity and emotion of university English teachers during curriculum reform in China. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.K.; Huang, Y.X.H.; Law, E.H.F.; Wang, M.H. Professional identities and emotions of teachers in the context of curriculum reform: A Chinese perspective. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 41, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, K.; Sleegers, P.; van de Ven, P.H. One teacher’s identity, emotions, and commitment to change: A case study into the cognitive-affective processes of a secondary school teacher in the context of reforms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B. The impact of mandated change on teachers. In The Sharp Edge of Educational Change: Teaching, Leading and the Realities of Reform; Bascia, N., Hargreaves, A., Eds.; Routledge Falmer: London, UK, 2000; pp. 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pease-Alvarez, L.; Thompson, A. Teachers working together to resist and remake educational policy in contexts of standardization. Lang. Policy 2014, 13, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, N.; van Dijk, M.; de Bot, K.; Lowie, W. The complex dynamics of adaptive teaching: Observing teacher-student interaction in the language classroom. IRAL-Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2022, 60, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, Y. Multilingualism and higher education in Greater China. J. Multiling. Multicult. Develop. 2019, 40, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Gao, X.; Xia, J. Problematising recent developments in non-English foreign language education in Chinese universities. J. Multiling. Multicult. Develop. 2019, 40, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zhang, H. Career Development of University Teachers of Less-Commonly Taught Foreign Languages: Challenges and Dilemmas. Foreign Lang. China 2017, 14, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Theory and methodology in researching emotions in education. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2007, 30, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, A.; Burns, A.; Ollerhead, S. ELT lecturers’ experiences of a new research policy: Exploring emotion and academic identity. System 2017, 67, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. From the imagined to the practiced: A case study on novice EFL teachers’ professional identity change in China. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 31, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sit, H.; Bao, M. Sustainable careers of teachers of languages other than English (LOTEs) for sustainable multilingualism in Chinese universities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ary, D.; Jacobs, L.; Sorensen, C.; Razavieh, A. Introduction to Research in Education, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.G. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Transaction: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Jiaoyubu Guanyu Jiaqiang Waiyu Feitongyong Yuzhong Rencai Peiyang Gongzuo de Yijian [Guidelines for Improving Languages Other than English (LOTE) Programs]. 2015. Available online: http://jyt.fujian.gov.cn/xxgk/zywj/201511/t20151106_3180034.htm (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Ministry of Education. Tuijin Gongjian Yidai Yilu Jiaoyu Xingdong [Schemes for Promoting the Construction of Education on the ‘Belt and Road’]. 2016. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2017/content_5181096.htm (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Tao, J.; Zhao, K.; Chen, X. The motivation and professional self of teachers teaching languages other than English in a Chinese university. J. Multiling. Multicult. Develop. 2019, 40, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Exploring dual-foreign-language education in comprehensive universities: Fudan University’s innovation. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 2020, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Guanyu Shenhua Gaoxiao Jiaoshi Kaohe Pingjia Zhidu Gaige De Zhidao Yijian [Guidelines for Deepening the Reform of Universities’ Teachers’ Evaluation System]. 2016. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s7151/201609/t20160920_281586.html (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Hargreaves, A. Educational change takes ages: Life, career and generational factors in teachers’ emotional responses to educational change. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wen, Q. The impact of a professional learning community on the development of university teachers instructing different foreign languages. Foreign Lang. World 2020, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. Changing Teachers, Changing Times: Teachers’ Work and Culture in the Postmodern Age; Cassell: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. The future of educational change: System thinkers in action. J. Educ. Chang. 2006, 7, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Q.; Gao, X. Sustainable professional development of German language teachers in China: Research assessment and external research funding. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).