Assessing Circular Economy Opportunities at the Food Supply Chain Level: The Case of Five Piedmont Product Chains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Section 2 shows the objectives and the design methodology that characterized the research, as well as the instrument and tools that have made it possible to carry out the investigation;

- Section 3, in accordance with the stages of the methodological structure presented in Section 2, reports a particular emphasis on the outcome of Desk-based Research, in particular describing the Academic and Sectoral Document Discovery (within which the scientific literature was analyzed), the Quantitative and Qualitative Data Analysis and the Supply Chain Mapping developed; furthermore, the results of the Stakeholder Engagement are summarized inside this section;

- Section 4 shows the meaningful challenges for the development and the expansion of integrated food policies through the definition of a series of cross-cutting solutions;

- Section 5 describes implications, limits, hypotheses, and future research directions about the Research Proposal developed.

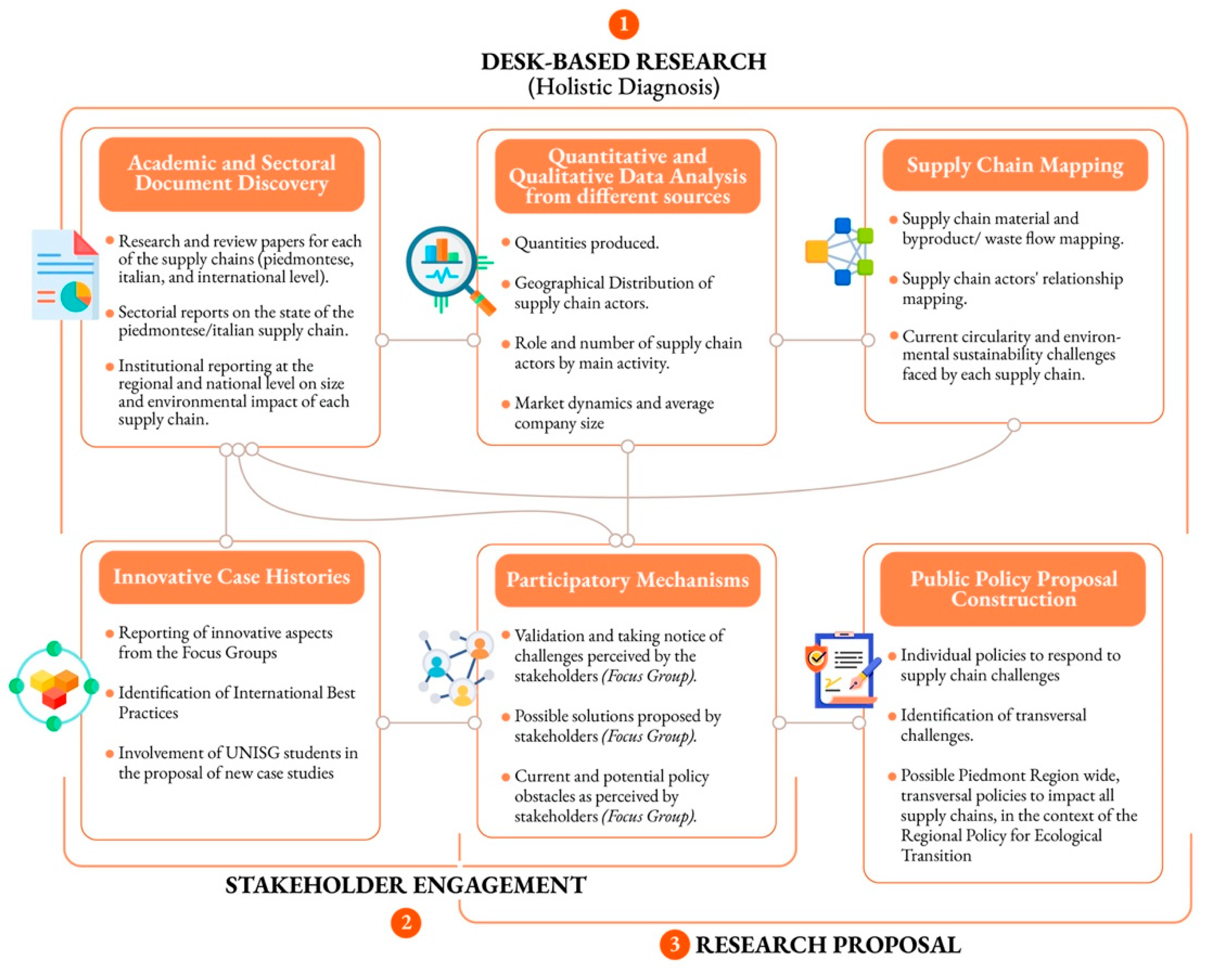

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives of the Project

- to identify priority issues for the agri-food system regarding the possibility of transition toward a model based on a better use of renewable resources, reuse of raw materials, and waste valorization;

- to identify and suggest regional system policies according to sustainability objectives in relation to the priority areas.

2.2. Instruments and Tools

- Academic and sectoral document discovery: as a primary step, and to better define the extent of each supply chain, relevant research papers and sectoral documents were researched. Using the keywords “waste”, “byproduct”, “waste management” and “circular economy”, followed by each of the individual supply chain names, in an academic search engine (Google Scholar) and in a scientific article database (Scopus), with a total number of 75 selected articles, ranging from scientific articles reporting on similar initiatives on a smaller or similar scale, to sectoral documents, used to better delineate the size and boundaries of each supply chain. In addition to supply chain structure and boundaries, the documents were also analyzed for information regarding the current practices of waste or by-product disposal, valorization and/or and treatment, as well as for the private and public sectors’ interests and understanding of the challenges currently present in the Piedmontese regional context. This step, using other terms, could also be called a literature review because it was performed to understand the scenario of the research proposal better and to analyze—at a micro level—the research gap identified. In fact, it consists of a thorough study review process of papers about the circular economy, food waste management, sustainable food supply chains, and local agri-food system. All the considerations developed during this phase have been inserted in the aforementioned text, in particular, in Section 1, Section 3 and Section 4.

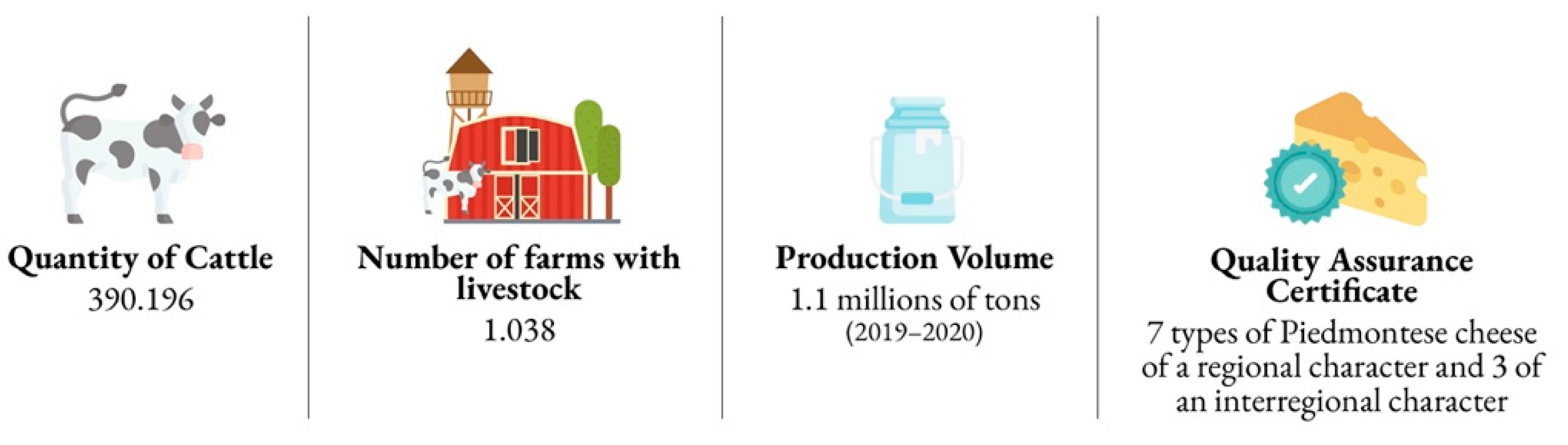

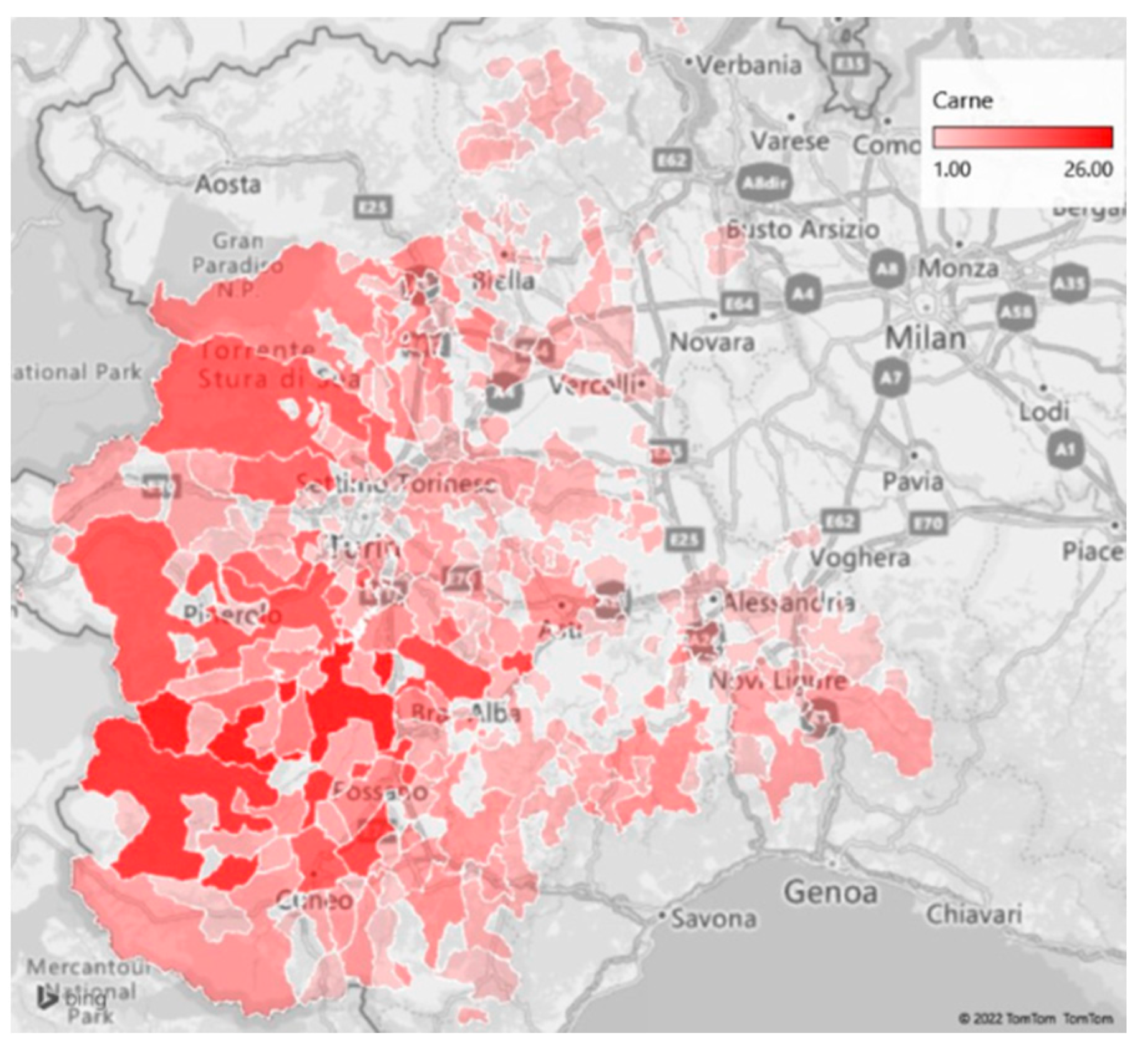

- Quantitative and Qualitative Data Analysis: once the current state and main challenges for each supply chain were taken into account, information regarding the distribution of actors in each step of the chain was procured by employing two datasets: one, provided by the Piedmont Region joint Chambers of Commerce (Unioncamere Piemonte) [50], containing statistical and location data for all the companies registered within the region, and the other by the University of Gastronomic Sciences’ Food Industry Monitor, a performance observatory containing historical financial data for the most relevant companies in the Italian food sector. Both datasets were filtered by only including the companies whose economic activity code (Codice ATECO) was within those belonging to the mapped supply chain, with a resulting total of 3261 records analyzed. In addition to individual company data, other statistical databases for each of the supply chains analyzed were taken into consideration, in order to better understand the complexity and scale of each one. Namely, the regional and national agricultural registries were consulted for a region-wide perspective on the data that is reported by each supply chain’s multiplicity of actors to the regional and national governments.

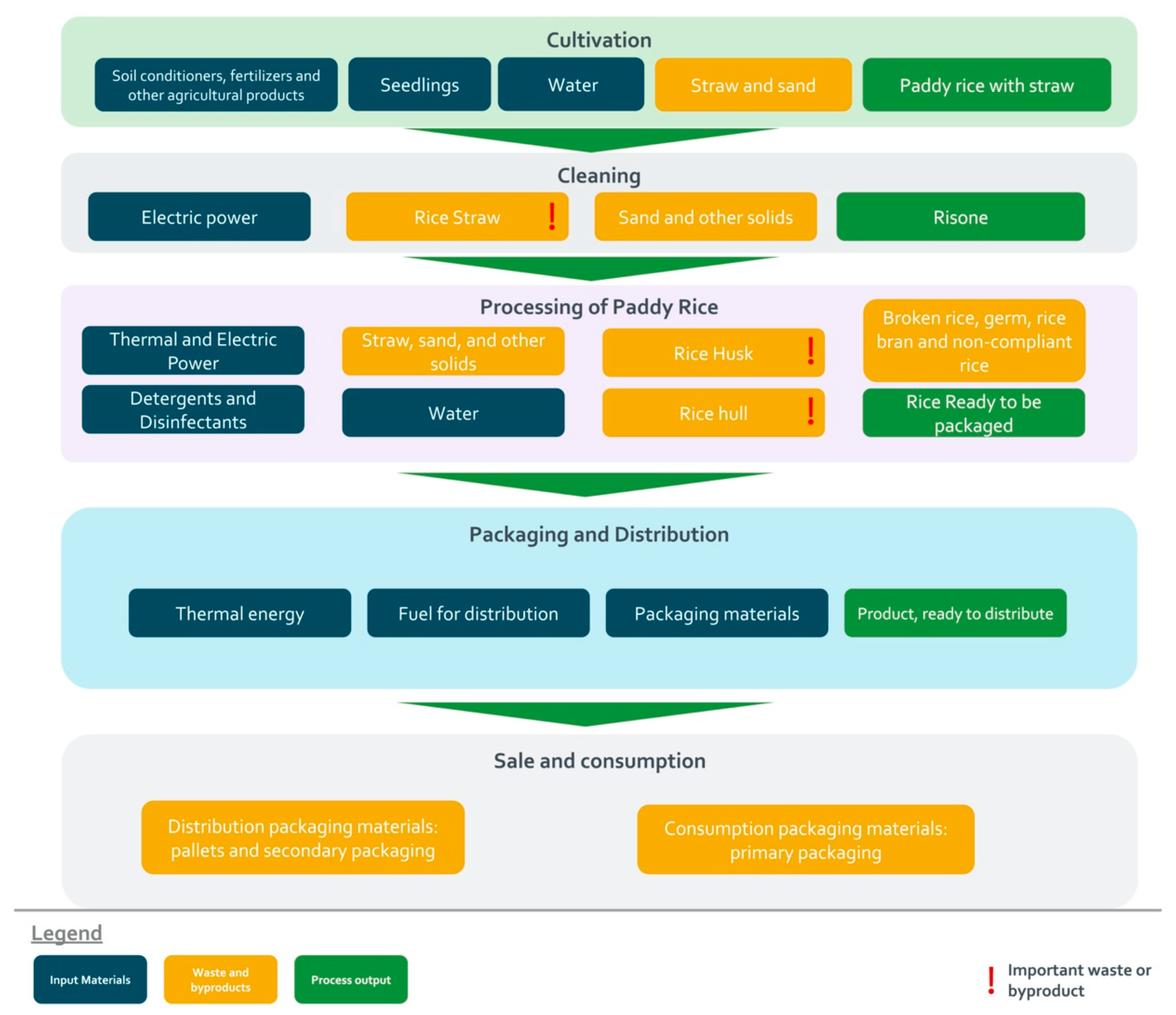

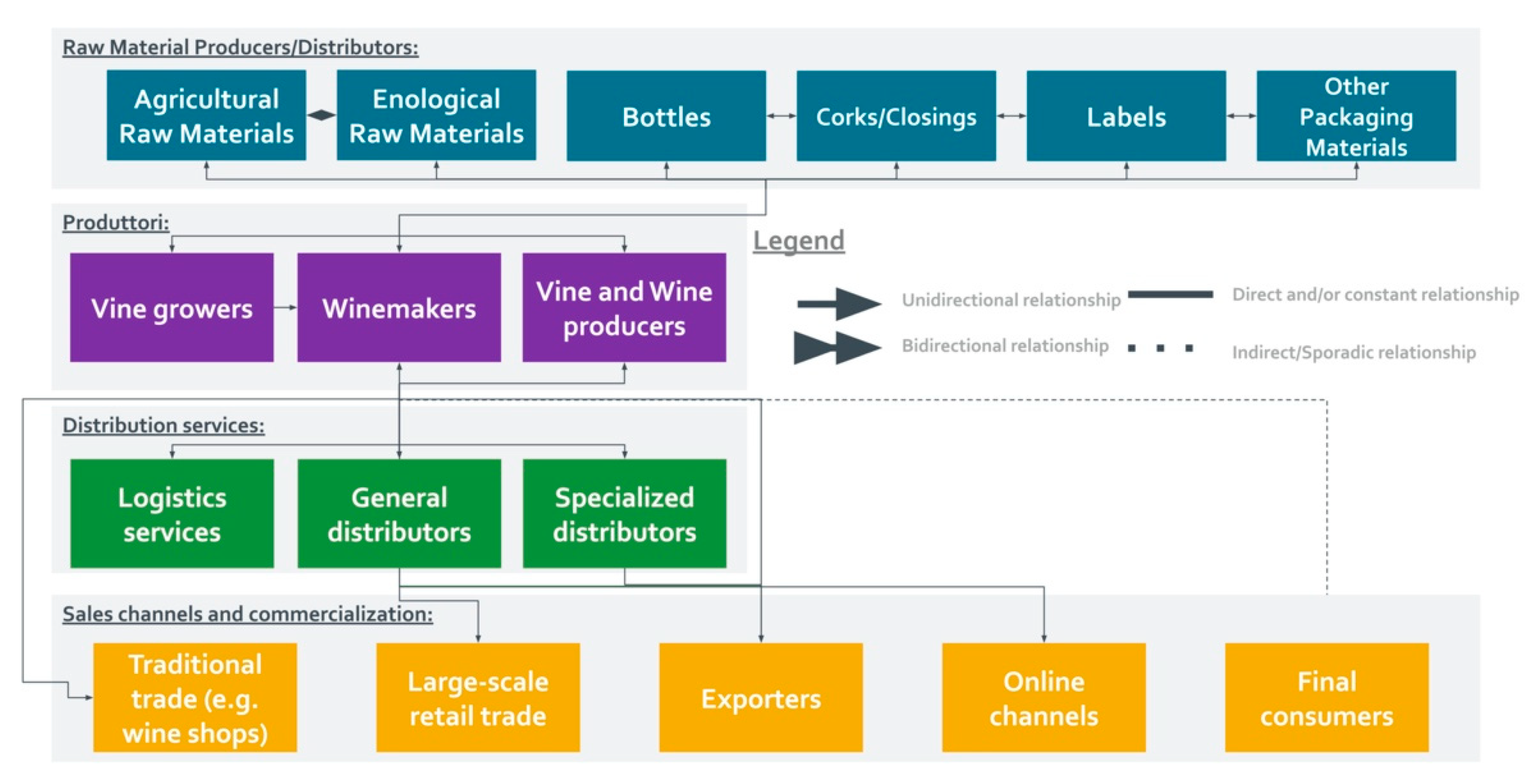

- Supply chain stage mapping: based on the information gathered in the document discovery stage, as well as the quantitative data gathered and analyzed, a simplified “map” of each supply chain was constructed; said map would feature the main actors in the supply chain as system nodes, as well as the financial, material, and information flows among them. The mapping covered the flow from direct material suppliers all the way to retail channels, including, in some cases, the actors involved in the treatment and valorization of waste and by-products, based on the level of connection to the main supply chain, and to the available information gathered. Following the development of each supply chain map, the research team validated their contents with actors present at different stages of each supply chain, who either attested to the accuracy of the mapping, as well as pointing out blind spots or missing nodes/connections. Having received this feedback, a definitive map for each supply chain, including the actors’ feedback, was constructed.

- Innovative case histories research: in parallel, in keeping with the practical, implementation-centered intention and goals of the project, a set of 28 innovative case studies, relevant to each of the five supply chains were studied and summarized, intended to be used as input for both the proposed solutions to challenges, and to foster conversation in the participatory mechanism sessions further ahead.

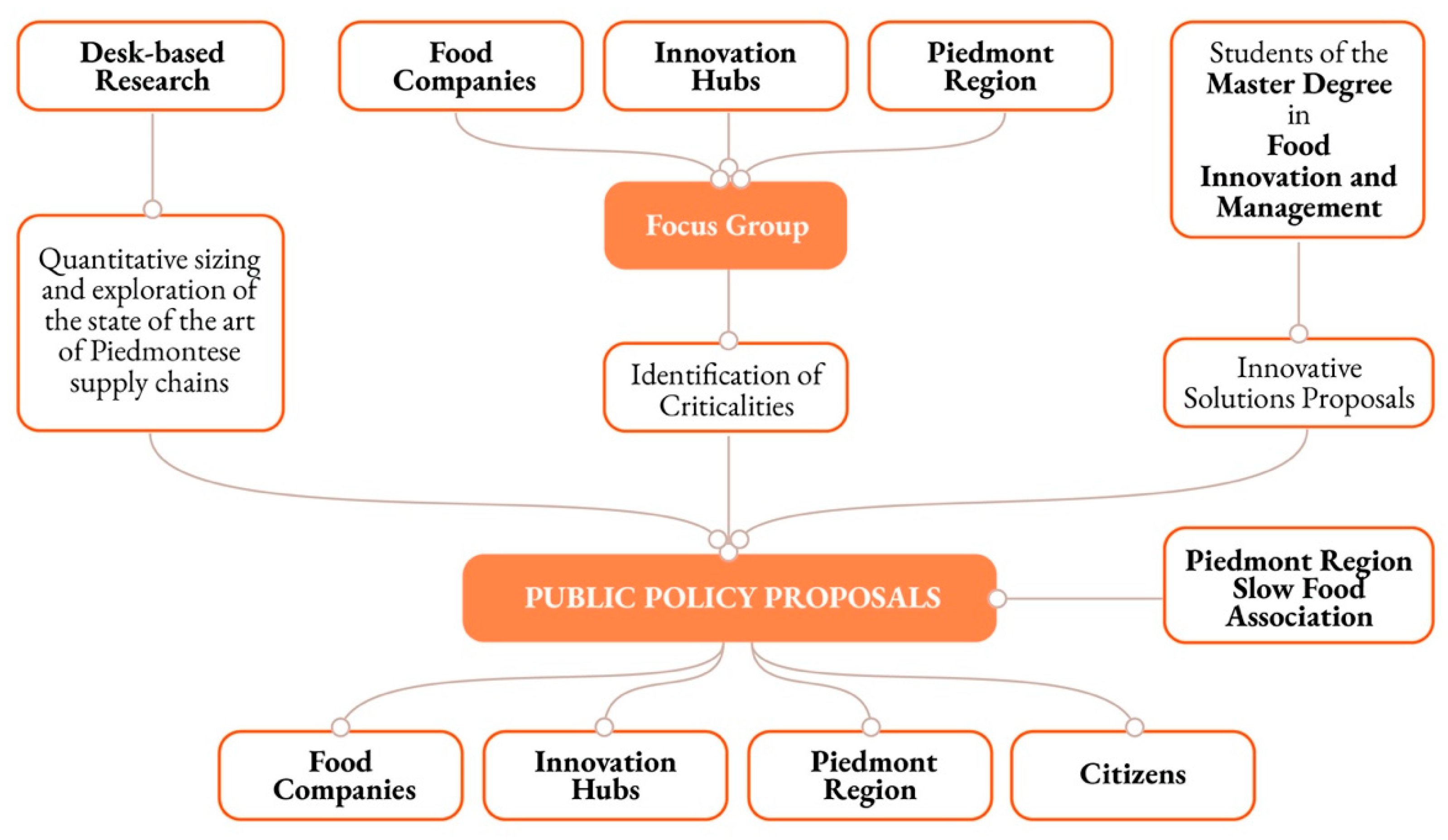

- Participatory mechanisms: while a better understanding of each supply chain was established by mapping and quantifying their dimension, complexity, and economic relevance at a regional level, the next step of the project was designed to include the personal experience of several actors from each supply chain, as well as their interaction with institutional representatives. This phase was conducted, in line with the scientific literature analyzed, on the topic of the circular economy, which revealed the need to involve stakeholders at the level of the supply chain in the development and evaluation of possible directions for the transition from a linear to a circular and more sustainable system, in order to understand potential, dormant assets and possible barriers [13]. The process followed therefore placed emphasis on the engagement of relevant stakeholders for contemporary agri-food circular economy research. Taking the project’s final objective of public policy development into account, it was decided that it was best to employ a participatory, deliberative approach to the validation of the quantitative analysis, as well as to the understanding of challenges faced by each of the supply chains. Therefore, a series of supply chain circularity and ecological transition-focused focus groups were designed and implemented.

- Data analysis and drafting of public policy proposals: as all necessary inputs were gathered, the following and final step was to synthesize and process the data gathered along every step of the research process and translate them into actionable recommendations for the Piedmontese regional government.

- Introduction to the University’s project and its objectives;

- Explanation of the context of the project at the European (Green Deal), national (SNSvS), and regional (SRSvS) levels;

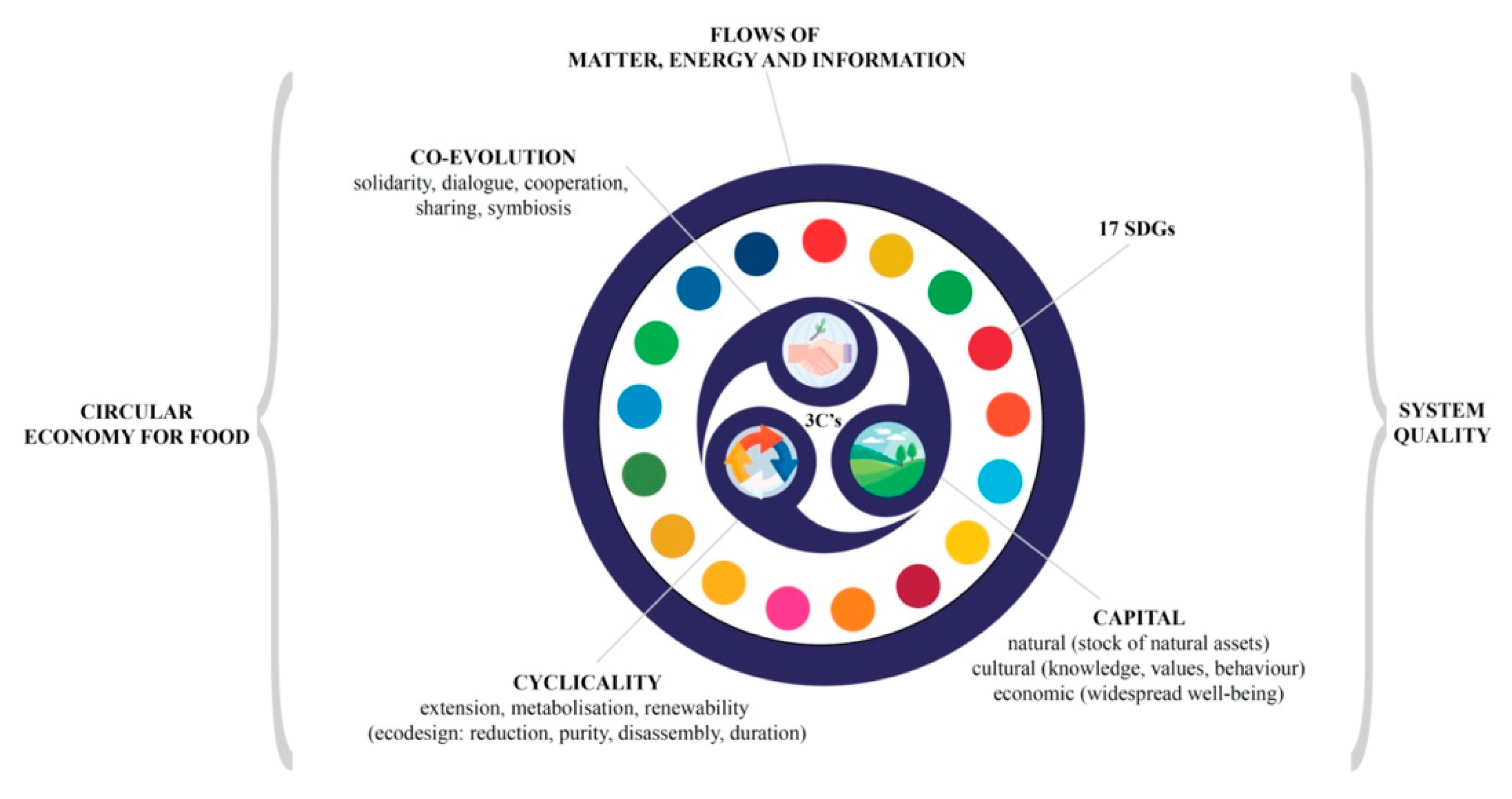

- Presentation of the UNISG vision of the Circular Economy for Food (3C);

- Validation of the quantitative, qualitative, and financial representation of the specific supply chain;

- Illustration of the main waste products and by-products of the supply chain under analysis;

- Emerging issues related to the application of circular activities or the implementation of circular practices that also address the management and valorization of the supply chain’s outputs;

- Presentation and identification of relevant case studies and virtuous business models of the circular economy applied to the agri-food sector, leaving a space for discussion among participants for their assessment of the feasibility of applying such examples in the Piedmont context;

- Further insight and discussion on the scenario of the circular economy in Piedmont.

2.3. Construction of Public Policy Proposals from the Information Gathered and Processed

3. Results

3.1. Examples of Project Outputs

3.1.1. Academic and Sectoral Document Discovery

3.1.2. Quantitative and Qualitative Data Analysis

3.1.3. Supply Chain Stage Mapping

3.2. Main Waste Products and By-Products Found by the Project

Innovative Case Study Research

3.3. Challenges and Obstacles to a Regional, Supply Chain-Level Transition

4. Discussion

- Affected supply chain: in particular, describing which supply chain they refer to;

- SDGs affected: describing which of the SDGs are affected by the opportunity;

- 3 Cs of Circular Economy for Food: indicating which 3 C they concern—Capital, Cyclicality, Coevolution;

- Related issues: describing which other transversal problems are referred to. In particular, reporting the content connection between the transversal opportunities and the individual issues. In particular, they refer to the contents present in the regional MAS.

- 45 recommendations/proposals for impacting actions on SRSvS divided among the five sectors most deeply involved in research innovation poles and research centers;

- 11 recommendations with a transversal approach (on the fivesupply chains);

- 20 indications on areas that should be explored through specific applied research (on the five supply chains).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Supply Chain | Waste or By-Product | Standard Disposal Methods | Disposal-Related Issues | Circular Opportunity of Valorization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wine | Prunings and Stalks |

|

|

|

| Grape Pomace |

|

|

| |

| Wine lees |

|

|

| |

| Waste water and filter cakes | Regular disposal | Difficult to manage |

| |

| Dairy and Cheese | Whey |

|

|

|

| Packaged expired and non-compliant milk at the factory |

|

|

| |

| Dairy and Cheese and Bovine Meat | Waste waters and Sludge |

|

|

|

| Manure |

|

|

| |

| Rice | Rice Straw |

|

|

|

| Rice Husk (lolla) |

|

|

| |

| Rice Hull (pula) |

|

|

| |

| Bottled Water | Plastic water bottles |

|

|

|

| Bovine Meat | Blood |

|

|

|

| Bovine Meat Rice Dairy and Cheese | Final packaging |

|

|

|

Appendix B

- Supply chain: in particular, describing which supply chain they relate to;

- SDGs affected: describing which SDGs they refer to;

- 3 Cs of the Circular Economy For Food: describing which 3 C they pertain to—Capital, Cyclicality, Coevolution;

- Related issues: describing other transversal problems concerned. In particular, reporting the content connection between the individual problems.

| N° | Transversal Issues | Supply Chains | SDGs Affected | 3 Cs of CEFF | Relationship to Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Climate Change |  |  |  | 2—Soil acidification 3—Air pollution 4—Biodiversity loss 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain |

| 2 | Soil acidification |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 3—Air pollution 4—Biodiversity loss 8—The lack of attention to animal welfare 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain |

| 3 | Air pollution |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 2—Soil acidification 4—Biodiversity loss 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production 6—The end of life of after-consumer packaging 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 4 | Biodiversity loss |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 2—Soil acidification 3—Air pollution 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production 8—The lack of attention to animal welfare 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain |

| 5 | Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 3—Air pollution 4—Biodiversity loss 7—The volatility of energy prices 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 6 | The end of life of after-consumer packaging |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 3—Air pollution 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production |

| 7 | The volatility of energy prices |  |  |  Social and economic Capital | 1—Climate Change 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production |

| 8 | The lack of attention to animal welfare |  |  |  | 2—Soil acidification 3—Air pollution 4—Biodiversity loss |

| 9 | Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes |  |  |  | 2—Soil acidification 3—Air pollution 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 10 | Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products |  |  |  | 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 11 | The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts |  |  |  | 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 12 | Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 2—Soil acidification 3—Air pollution 4—Biodiversity loss 8—The lack of attention to animal welfare 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives 14—Difficulty of dialogue and confrontation of companies/innovation poles with regional institutions |

| 13 | Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |  |  |  | 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production 6—The end of life of after-consumer packaging 8—The lack of attention to animal welfare 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products |

| 14 | Difficulty of dialogue and confrontation of companies/innovation poles with regional institutions |  |  |  | 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

References

- Ellen Macarthur Foundation (FME). Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/x8ay372a3r11-k6775n/@/preview/1?o (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Buchanan, R. Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Des. Issues 1992, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.H. Systemic Design Principles for Complex Social Systems. Soc. Syst. Des. 2014, 1, 91–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mirabelli, G.; Solina, V. Optimization strategies for the integrated management of perishable supply chains: A literature review. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2022, 15, 58–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. Vita e Natura—Una Visione Sistemica; Aboca: Sansepolcro, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L.V. General Systems Theory; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Peruccio, P.; Savina, A. The planning of a territorial network among food, health and design. Agathón|Int. J. Archit. Art Des. 2020, 8, 262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Bistagnino, L.; Cantino, V.; Gibello, P.; Puddu, E.; Zaccone, D. Il Settore Agroalimentare. Scenari e Percorsi di Crescita Sostenibile; Slow Food Editore: Bra, Italy; Deloitte & Touche S.p.A: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bistagnino, L. Systemic Design—Designing the Productive and Environmental Sustainability; Slow Food Editore: Bra, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, P. La cultura contadina: Le radici del pensiero circolare. In Circular Economy for Food. Materia, Energia e Conoscenza in Circolo; Fassio, F., Tecco, N., Eds.; Edizioni Ambiente: Milano, Italy, 2018; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, B.; Sessa, M.; Sica, D.; Malandrino, O. Towards Circular Economy in the Agri-Food Sector. A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarini, O.; Stahel, W.R. The Limits to Certainty: Facing Risks in the New Service Economy; Kluwer Academic: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: Milano, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacina, R. Economia Circolare: Il Nuovo Paradigma Della Sostenibilità. Master’s Thesis, LUISS—Libera Università Internazionale degli Studi Sociali Guido Carli, Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bompan, E.; Brambilla, I.N. Che Cosa è l’Economia Circolare? Edizioni Ambiente: Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Un Green Deal Europeo. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_it (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_it (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Rockström, J.; Sukhdev, P. How Food Connects all the SDGs; Opening KeyNote Speech at the 2016 EAT Forum; Stockholm Resilience Center: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, G.; Tennant, M.; Blomsma, F. Business and production solutions: Closing the Loop and the circular economy. In Sustainability: Key Issues; Kopnina, H., Shoreman-Ouimet, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_20_437 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- La Strategia Nazionale per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. Available online: https://www.mite.gov.it/pagina/la-strategia-nazionale-lo-sviluppo-sostenibile (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Pereira, L.M.; Drimie, S.; Maciejewski, K.; Tonissen, P.B.; Biggs, R. Food system transformation: Integrating a political–economy and social–ecological approach to regime shifts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bistagnino, L. MicroMACRO. Micro Relazioni Come Rete Vitale Del Sistema Economico e Produttivo; Edizioni Ambiente: Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnino, R.; Milbourne, P. Food system transformation: A progressive place-based approach. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Transforming Food and Agriculture to Achieve the SDGs: 20 Interconnected Actions to Guide Decision-Makers. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/I9900EN/i9900en.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Nutrition Connect. Available online: https://symposium.bayes.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/504621/7643_Brief-5_Policy_coherence_in_food_systems_2021_SP_AW.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Barbero, S. Systemic Design Method Guide for Policymaking: A Circular Europe on the Way; Allemandi: Turin, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eraydin, A. The role of regional policies along with the external and endogenous factors in the resilience of Regions. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2015, 9, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Role of Regional Policy in the Future of Europe. European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/panorama/pdf/mag39/mag39_en.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Ciaffi, A.; Odone, C. Le Politiche Europee e Il Ruolo Delle Regioni: Dalla Teoria Alla Pratica; Centro Interregionale Studi e Documentazione: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Calori, A.; Magarini, A. Food and the Cities—Politiche Del Cibo Per Città Sostenibili; Edizioni Ambiente: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. Future Food Systems: For People, Our Planet, and Prosperity. London, UK. Available online: https://www.glopan.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Foresight-2.0_Future-Food-Systems_For-people-our-planet-and-prosperity.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Deakin, M.; Borrelli, N.; Diamantini, D. The Governance of City Food Systems: Case Studies from Around the World; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, R.; Green, D.; Guijt, I.; Walsh, M.; English, R.; Cairney, P. Using evidence to influence policy: Oxfam’s experience. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, P. The Barriers to Evidence Based Policymaking in Environmental Policy. 2015. Available online: https://paulcairney.wordpress.com/2015/08/21/the-barriers-to-evidence-based-policymaking-in-environmental-policy/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Den Boer, A.C.; Kok, K.P.; Gill, M.; Breda, J.; Cahill, J.; Callenius, C.; Caron, P.; Damianova, Z.; Gurinovic, M.; Lähteenmäki, L.; et al. Research and innovation as a catalyst for food system transformation. Trends. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Cities—United Nations Sustainable Development Action 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Jurgilevich, A.; Birge, T.; Kentala-Lehtonen, J.; Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Pietikainen, J.; Saikku, L.; Schosler, H. Transition towards Circular Economy in the Food System. Sustainability 2016, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPES FOOD. Verso Una POLITICA Alimentare Comune Per l’Unione Europea. Le Riforme Politiche e Gli Aggiustamenti Necessari Alla Creazione di Sistemi Alimentari Sostenibili in Europa. Available online: https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/CFP_ExecSummary_IT.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Hawkes, C.; Parsons, K. Brief 1: Tackling Food Systems Challenges: The Role of Food Policy. In Rethinking Food Policy: A Fresh Approach to Policy and Practice; Centre for Food Policy: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lever, J.; Sonnino, R. Food system transformation for sustainable city-regions: Exploring the potential of circular economies. Reg. Stud. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, T.; Hernandez, R.; Mawle, R. Sustainability: Methods and practices. In The Handbook of Design for Sustainability; Walker, S., Giard, J., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2013; pp. 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fassio, F.; Tecco, N. Circular Economy for Food: Materia, Energia e Conoscenza in Circolo; Edizioni Ambiente: Milan, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. One Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Fassio, F.; Cionchi, E.; Tondella, A. The Circular Economy for Food in Future Cities. Good Practices That Define Smart Food. Agathón|Int. J. Archit. Art Des. 2020, 8, 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fassio, F. The 3 C’s of the Circular Economy for Food. A conceptual framework for circular design in the food system. Diid Disegno Ind. Ind. Des. 2021, 73, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Strategia di Sviluppo Sostenibile. Verso un Presente Sostenibile. Available online: https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/temi/strategia-sviluppo-sostenibile (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- TELEMACO-INFOCAMERE. Available online: https://www.registroimprese.it/area-utente#elenchi (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Slowfood.It. Available online: https://www.slowfood.it (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Ministero della Transizione Ecologica. Piano Per La Transizione Ecologica. Available online: https://www.mite.gov.it/pagina/piano-la-transizione-ecologica (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Fiore, E.; Stabellini, B.; Tamborrini, P. A Systemic Design Approach Applied to Rice and Wine Value Chains. The Case of the InnovaEcoFood Project in Piedmont (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, E.; Capri, E.; Pulina, G. La Sostenibilità Delle Carni e Dei Salumi in Italia: Salute, Sicurezza, Ambiente, Benessere Animale, Economia Circolare e Lotta Allo Spreco; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M.; Clinton, B. The Upcycle: Beyond sustainability—Designing for Abundance; Melcher Media, North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, R.D.; Jason, C. Agriculture 4.0: Broadening Responsible Innovation in an Era of Smart Farming Frontiers. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Parente, M.; Sedini, C. D4T—Design Per i Territori—Approcci, Metodi, Esperienze; List Editore: Trento, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boehnert, J. Design, Ecology, Politics. Towards the Ecocene; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Soma, T.; Wakefield, S. The emerging role of a food system planner: Integrating food considerations into planning. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2011, 2, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Supply Chain | Name of the Case History | Circular Business Model/ Practice Shown |

|---|---|---|

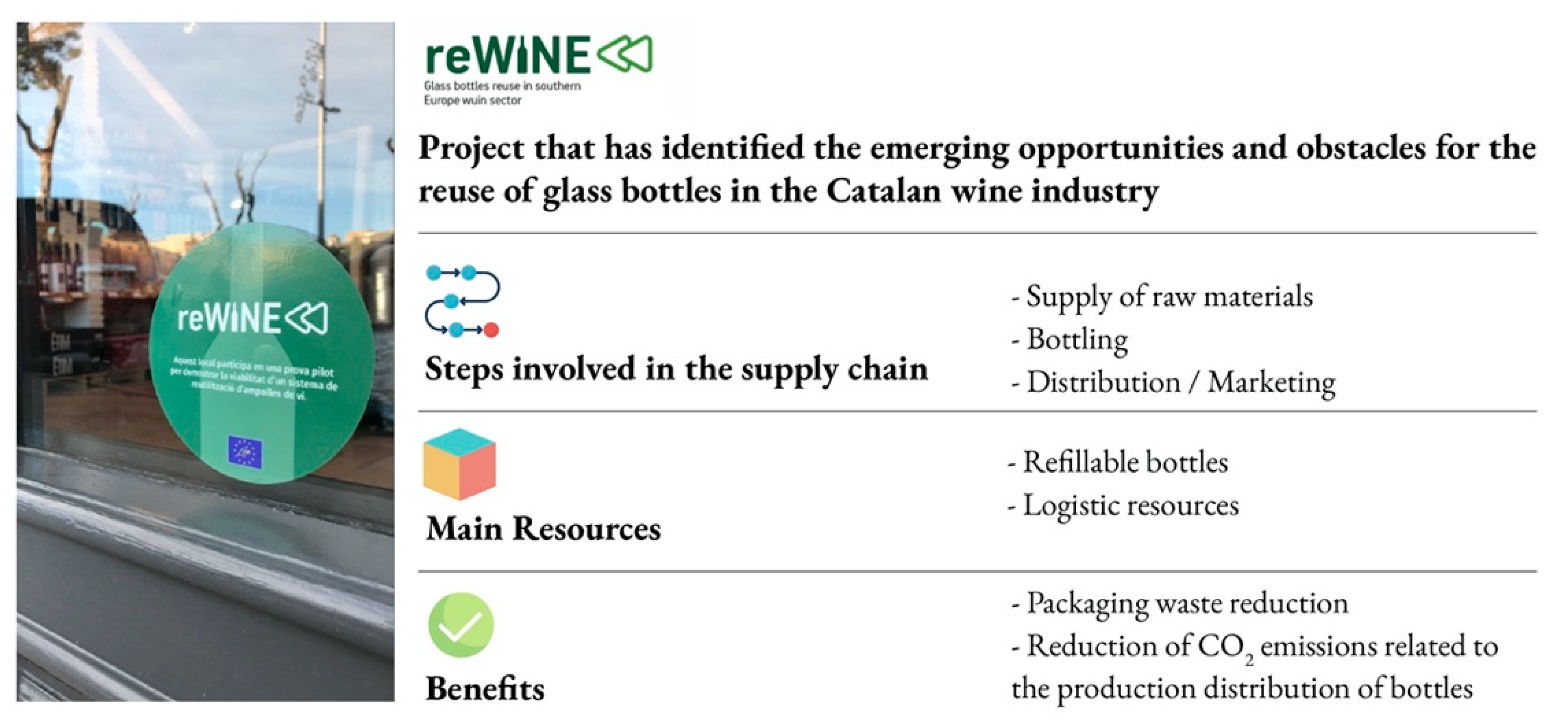

| Wine | reWINE | System for the return and reuse of glass wine bottles at a local level |

| VEGEA | Valorization of grape pomace for manufacturing of leather-like fabrics | |

| Caviro group | Production of bioenergy and compost from waste from pruning and destemming | |

| Poliphenolia | Extraction of grape pomace polyphenols for cosmetics production | |

| NOMACORC | Adoption of cork substitutes from recycled and bio-based alternatives to cork wood | |

| Milk and Cheese | KRINGLOOP WIJZER | Monitoring soil nutrient cycle |

| FrieslandCampina | Tool for assessment of biodiversity improvement in the dairy sector | |

| BIOCOSI’ | Production of bioplastics from wastewater | |

| ORIGAMI Organics | Production of fabrics based on milk waste | |

| fluence | Biogas production from ricotta whey, buttermilk, and wastewater | |

| UNTER/EGGER | Production of cosmetics based on nutrients extracted from whey | |

| Milk Brick | Production of building materials based on milk waste | |

| Rice | VIPOT | Production of biodegradable pots based on rice husk |

| GENIA BIOENERGY | Biogas production from rice straw | |

| IKEA India | Production of furniture items from rice straw | |

| RICE HOUSE | Production of building materials based on rice waste (husk, chaff, straw) | |

| Water | PABOCO | Bottles made from sustainably sourced wood fibers |

| Carlsberg | Reduction in plastic use in beverage multipacks | |

| E6PR | Biodegradable and compostable secondary packaging for beverages (multi-pack rings) | |

| Ferrarelle | Bottles composed of 100 percent R-PET | |

| VERITAS | Returnable glass bottle service in partnership with retailer | |

| Pfand System-Germany | Public bottle return system with incentives for adoption | |

| Bovine Meat | BovINE | Reward systems to farmers who practice regenerative agriculture |

| Water2Return/Bioazul | Extraction of nutrients in slaughterhouse wastewater | |

| Circ4Life/Alia | Co-creation of circular synergies among various actors in the supply chain | |

| La Granda | ‘Symbiotic farming’ for animal husbandry | |

| BTS | Biogas production through wastewater | |

| Fileni | Biodegradable and recyclable packaging for meat products |

| N° | Relevant Transversal Opportunities | Affected Supply Chains | SDGs Affected | 3 Cs of CEFF | Relationship to Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biogas production through shared plants for the recovery of waste and by-products of organic nature |  |  |  | 3—Air pollution 7—The volatility of energy prices 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 2 | Use of regenerative cultural practices and symbiotic agriculture for biodiversity presentation and resilience |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 3—Air pollution 4—Biodiversity loss 8—The lack of attention to animal welfare 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 3 | Use of by-products for green building, to propose an alternative to traditional materials made from non-renewable resources |  |  |  | 3—Air pollution 7—The volatility of energy prices 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 4 | Cross-sectional research on the production of bioplastics from organic packaging waste |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 3—Air pollution 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production 6—The end of life of after-consumer packaging 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives 14—Difficulty of dialogue and confrontation of companies/innovation poles with regional institutions |

| 5 | Creation of joint participatory tables for the common achievement of competitiveness and sustainability objectives |  |  |  | 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives 14—Difficulty of dialogue and confrontation of companies/innovation poles with regional institutions |

| 6 | Using R-PET for water bottles |  |  |  | 1—Climate Change 3—Air pollution 5—Exploitation of non-renewable resources for packaging production 6—The end of life of after-consumer packaging 14—Difficulty of dialogue and confrontation of companies/innovation poles with regional institutions |

| 7 | Extraction of nutrients from processing and manufacturing waste and by-products for pharmaceutical and cosmetic production |  |  |  | 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 11—The low valorization of organic waste/subproducts 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives |

| 8 | Realization of spaces that exploit the sharing economy for the creation of economies of scale |  |  |  | 7—The volatility of energy prices 9—Management and treatment of wastewater from production processes 10—Logistics for the management of waste/organic by-products 12—Lack of communication of information or best practices among the various players in the same supply chain 13—Individual and little collective effort in executing and promoting circular initiatives 14—Difficulty of dialogue and confrontation of companies/innovation poles with regional institutions |

| N° | Transversal Public Policy Proposals | Affected SDGs | 3C of CEFF |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Promote business participation in specific funding programs aimed at boosting agribusiness investments to improve the competitiveness of the agricultural sector, ensure sustainable management of natural resources, and promote climate actions, achieve balanced territorial development of rural economies and communities (supply chain and district contracts, RDP 2014–2022) |  |  |

| 2 | Promote new forms of territorial aggregation between enterprises aimed at fostering innovation in agribusiness and the integration of activities characterized by territorial proximity (food district contracts) |  |  |

| 3 | Involvement of stakeholders through the establishment of specific working tables to identify shared solutions with impacts on the community |  |  |

| 4 | Advisory activities and accompaniment of economic operators toward the development of a by-product and waste supply chain and to the development of new sustainable materials from them. |  |  |

| 5 | Connecting the regional economic tissue with research and development facilities (Piedmont universities, research institutions, innovation hubs, etc.) by enhancing their expertise for positive spillover to their local area |  |  |

| 6 | Promoting the digitization of bureaucracy and its simplification/streamlining |  |  |

| 7 | Mapping the supply chain for by-products and waste in the Piedmont region |  |  |

| 8 | Promote the provision of training courses aimed at practitioners focused on sustainable production systems, facilitating access to resources, best practices, and useful tools |  |  |

| 9 | Involvement of stakeholders (municipalities, farmers, restaurateurs, teachers, consumers, recycling operators) by setting up roundtables to promote conscious and responsible consumption by the citizenry |  |  |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fassio, F.; Borda, I.E.P.; Talpo, E.; Savina, A.; Rovera, F.; Pieretto, O.; Zarri, D. Assessing Circular Economy Opportunities at the Food Supply Chain Level: The Case of Five Piedmont Product Chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710778

Fassio F, Borda IEP, Talpo E, Savina A, Rovera F, Pieretto O, Zarri D. Assessing Circular Economy Opportunities at the Food Supply Chain Level: The Case of Five Piedmont Product Chains. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710778

Chicago/Turabian StyleFassio, Franco, Isaac Enrique Perez Borda, Elisa Talpo, Alessandra Savina, Fabiana Rovera, Ottavia Pieretto, and Davide Zarri. 2022. "Assessing Circular Economy Opportunities at the Food Supply Chain Level: The Case of Five Piedmont Product Chains" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710778

APA StyleFassio, F., Borda, I. E. P., Talpo, E., Savina, A., Rovera, F., Pieretto, O., & Zarri, D. (2022). Assessing Circular Economy Opportunities at the Food Supply Chain Level: The Case of Five Piedmont Product Chains. Sustainability, 14(17), 10778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710778