1. Introduction

Enterprises and supply chains are increasingly operating in an environment or reality that four concepts can define: (1) variable or volatile indicates that changes are often chaotic and unpredictable, which in turn affects the volatility and obsolescence of long-term plans; (2) uncertain means that under conditions of uncertainty, a low level of understanding of events and problems that arise does not take into account inferences from the past and experience; (3) complex determines that the influence of various external factors (in terms of number and nature) causes difficulties in identifying the cause-effect chain of actions taken and emerging problems; and (4) ambiguous indicates that business challenges also concern unclear situations, incorrectly read signals from the environment, ambiguity, and lack of experience in a similar problem. For this article, we will refer to the described environment of the functioning of modern supply chains as VUCA reality. The functioning of supply chains in such an environment has a powerful impact on the day-to-day activities of individual chain links and the relationships and methods of interaction between them. The global attitude to the management of logistics networks is also changing. The efficiency of logistic handling of product flows continues to be critical, but today it competes with the need to design processes resistant to disruption. This manifests itself in a new approach to resource management, in which the stock (reserve) does not always mean waste, but more and more often a strategy of building resistance to emerging uncertain adverse events.

Unpredictable changes (VUCA reality) in business bombard you from all sides. The changes that occur on a global scale relate to, among others: (1) dynamic development of technology and production organization (Industry 4.0), which use innovative technological solutions; (2) particularly dynamic global changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences for the sustainability and continuity of supply chains; and (3) significant changes in consumer behavior, which are, among other things, the result of the global COVID-19 pandemic, and which affected the operational activity of supply chains [

1]. When making decisions and taking actions in supply chains, managers look for the linearity of events and solutions to problems in a cause-and-effect manner. However, they become helpless in the face of the events they experience in the often highly volatile business reality, where the warning signals are barely perceptible. As a result, we get a picture of an extremely volatile and unpredictable business environment in which vulnerable supply chains operate.

The following research questions were asked in the paper:

The problem of supply chain management has been of researchers’ interest since the 1980s. In the presented work, however, it has been presented in an innovative and perspective approach. No studies on the research results have been found that would indicate the possible implementation time of the studied idea in VUCA practice and reality. This progressive approach develops threads that increase the body of theoretical and practical knowledge. At the same time, the work is of an applied nature, presenting the results of research to solve specific practical needs for business organizations, and including suggestions for improving supply chains.

The article aims to present the results of research conducted among experts using the Delphi method and the conclusions drawn on this basis. The structure of the work was designed to answer the research questions posed above. Therefore, in

Section 2, the authors presented the results of a literature review on research on the concept of Supply Chain Resilience (SCR).

Section 3 describes the stages of the procedure in the adopted research methodology. Then,

Section 4 presents the results of empirical research.

Section 5 presents a discussion regarding the results of the conducted research. The main conclusions are presented in

Section 6.

2. Supply Chain Resilience—Theoretical Approach

Research has shown that every activity in the supply chain has inherent risks that may cause unexpected disruption [

2,

3]. In recent years, enterprises have been exposed to operational disruptions and adverse events that periodically affect their ability to manufacture and distribute their products. These events included, among other things, natural disasters, financial and fuel crises, geopolitical turmoil, acts of terrorism, and pandemics [

4]. Their impact on the activities of enterprises is described, among other things, in [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The scale of these events’ consequences raised scientists’ and practitioners’ awareness of the need to minimize the impact of disruptions by building more resilient supply chains [

11]. For this reason, in the last twenty years, there has been an increasing interest in the concept of supply chain resilience (SCR). We define resilience as companies’ capability to anticipate crises, identify risks, increase their impacts, adapt and respond quickly to threatening disruptions or vulnerabilities in the supply chain, and return to normal [

12]. Resilience is not simply about recovery after a disrupting event, but about the ability to adapt and transform [

13].

The initial period of this research falls in the first years of the 21st century when the first publications appeared, the authors of which made an effort to define this new strategy of shaping supply chains [

14,

15]. Although the amount of research in this area has been steadily increasing since then, there is still no final consensus on how to define SCR [

16]. However, it is worth noting that despite significant variations in the understanding of supply chain resilience, several key elements of this concept can be identified based on the applicable definitions. These are [

17]: anticipating unforeseen disruptive events; withstanding disruptions; responding quickly to disruptions; recovering from disturbances; and returning to steady-state conditions. The definition proposed by Carvalho et al. [

18] was adopted for this article. They define SCR as “concerned with the system’s ability to return to its original state or a new, more desirable one after experiencing a disturbance and avoiding the occurrence of failure modes”. It should be emphasized, however, that according to the definition of Brandon-Jones et al. [

19], the system’s return to the desired state after a disturbance should be achievable within an acceptable period. It is also worth noting that although most of the formulated definitions do not focus on the costs of building the resilience of the supply chain [

17], this aspect is still crucial from a business point of view. Excessively high costs of implementing a resilience strategy may constitute one of the significant barriers related to its implementation. For this reason, Haimes et al. [

20] emphasize that resilience aims to recover the desired states of a system within a sufficient time and at an acceptable cost. In line with this approach, Ivanov et al. [

21,

22] emphasize in their research that disruptions should be mitigated through cost-efficient recovery policies.

Research on the SCR strategy is primarily focused on searching for an action strategy that will allow companies to build resilience in their supply chains. A literature review by Tukamuhabwa et al. [

11] allowed to distinguish 24 such strategies that contemporary researchers describe. These strategies and sample articles relating to them are presented in

Figure 1.

Tukamuhabwe et al. [

11] divided the described strategies into two groups: proactive and reactive. Eligibility for each group is based on the answers to two questions: when the action is activated and why. Proactive strategies create the ability to predict upcoming disruptions and plan activities (prepare, proactively plan, prevent, anticipate). In contrast, reactive strategies build the ability to react and respond well to mitigate the disruptions (respond, adapt, resist, cope, and react). It is worth noting that some strategies, such as supply chain collaboration, increasing visibility, and use of information technology, can be both proactive and reactive. It is also worth noting that in the conducted research, more attention is paid to the development of proactive strategies than reactive ones, which can also be seen in

Figure 1. This may be due to the fact that these strategies allow companies to better prepare for potential adverse events as part of the improvement of logistics processes. However, as noted by Tukamuhabwa et al. [

11], managers may be reluctant to implement proactive strategies because they require investment in solutions to mitigate potential disruptions that may not eventually occur. This approach to improvements aimed at building the resilience of the supply chain may be one of the primary implementation barriers to this concept.

Radhakrishnan et al. [

23] defined “key capabilities” of high-reliability organizations in their research. They include flexibility, velocity, visibility, and collaboration. On the other hand, based on literature studies, Soni et al. [

24] distinguished ten factors that build resilience in supply chains. These included: agility; collaboration among players; information sharing; sustainability in SC; risk and revenue sharing; trust; visibility; risk management culture; adaptive capability; and SC structure. However, as Gu et al. [

25] emphasized, information technology is most important in building resilience, which supports information sharing and SC visibility.

The global COVID-19 pandemic has changed the approach to building supply chain resilience. The unprecedented and unusual situation that prevailed around the world strengthened the need for progress in research on the resilience of supply chains [

26]. At the same time, however, the approach to building resilience has changed. An example can be the research conducted by Ivanov [

27], who proposed four strategies for adaptation to the time of a pandemic. In his opinion, the resilience of supply chains is currently determined by: SC network intertwining; scalability; substitution; and repurposing production systems. Therefore, the lack of implementation of these strategies may constitute a barrier to building the resilience of supply chains.

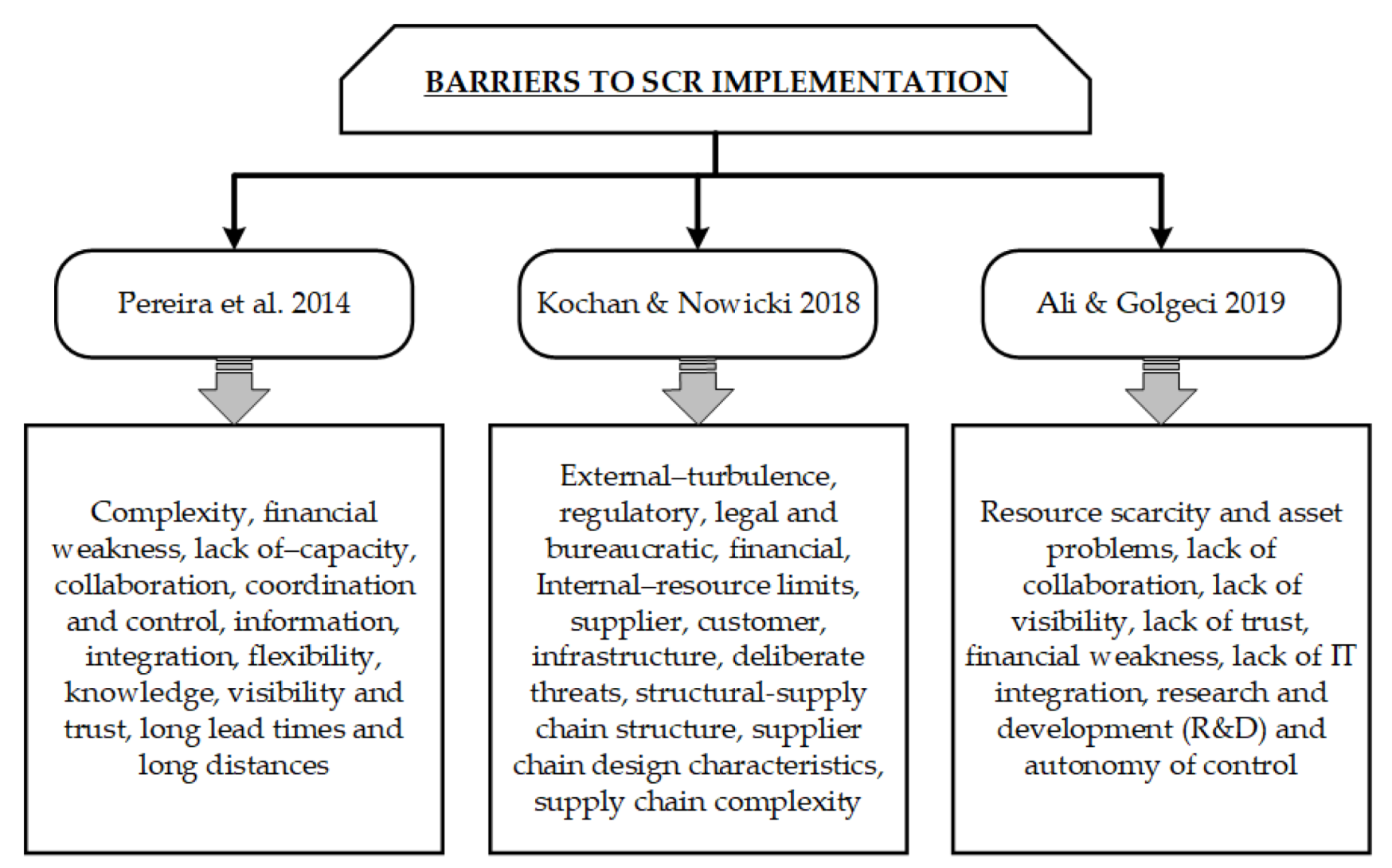

The turbulent and unstable environments in which modern supply chains operate generate numerous barriers to building resilience. Meanwhile, despite multiple publications on building the resilience of supply chains, few researchers focus on analyzing the existing barriers [

28]. Three articles presented the identification of such barriers based on the review’s systematic literature [

29,

30,

31]. The identified main barriers described in these publications are presented in

Figure 2.

Due to the priority importance of identifying the current implementation barriers for the further development of the SCR concept, and due to the existing research gap identified, among other things, by Agarwal and Seth [

28], we took up the challenge of conducting research in this area.

3. Research Methodology

The research results presented in the article are part of the project entitled “Identification and classification of theoretical, global trends and directions of development of supply chains”, financed under the MINIATURE program. The aim of the project was: (1) identification and classification of theoretical, global trends and directions of development of supply chains in the context of global changes; and (2) assessment of the development potential of the identified trends by experts using the Delphi method. Academic experts dealing with the subject of supply chains participated in the study. The study addressed two research questions of the MINIATURE project: (1) what are the theoretical, global trends and directions of supply chain development that have appeared over the years?; and (2) what is the development potential of the identified trends in the research area? [

1]. The key to a reliable measurement of the phenomenon of interest to us is the selection of an appropriate research method and definition of the research procedure. The research procedure organizes the individual stages of empirical research, the system of applied methods, and research tools. It is crucial due to the purposefulness of the research problem posed, and as a result, also of its solution.

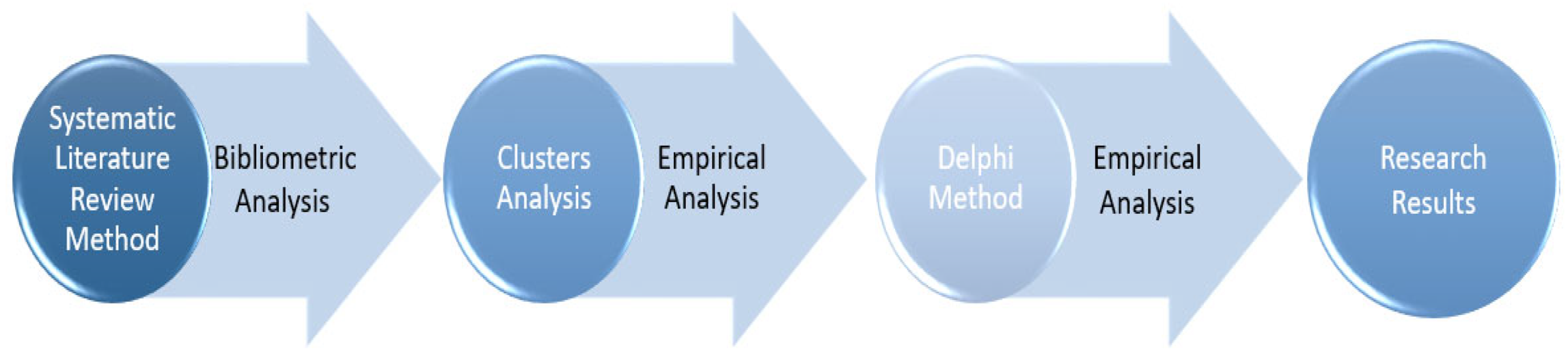

Figure 3 shows the general approach used in the conducted research.

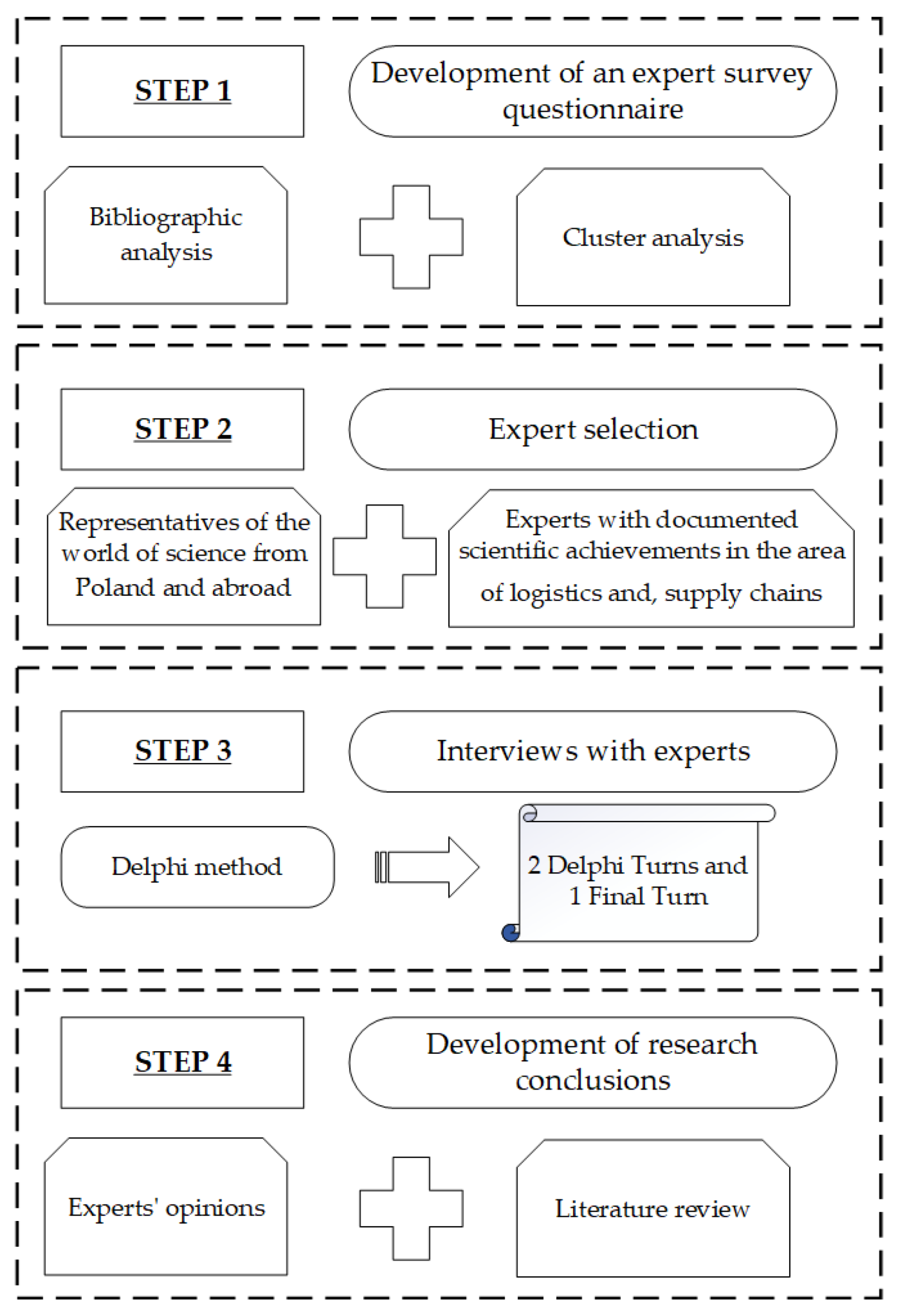

The aim of the article is to present the results of the study of the phenomenon related to SCR, which were obtained through an interview conducted with the Delphi method. The research procedure for the analyzed area is presented in

Figure 4.

The literature review and the Delphi method were selected to seek answers to the defined research questions. Therefore, the first stage of the research procedure is to prepare a questionnaire that will be the basis for collecting information from experts participating in the research. This stage is critical from the point of view of the proper preparation of the research. For this reason, the recommendations, questions, and the form of the answers provided will determine the quality of the obtained results and the correctness of inference. According to the adopted general research approach presented in

Figure 3, an expert survey questionnaire was developed based on the bibliographic analysis and cluster analysis (knowledge visualization). As a result, when creating the questionnaire, the results obtained from the conducted literature research were used.

The second stage of preparation for the research was the selection of experts. Relying on experts’ intellectual potential has essential consequences in research methodology. The Delphi method is as accurate and reliable as experts who participate in it. Therefore, the selection of experts for the study was not accidental. The group of experts consisted of representatives of the world of science from leading centers in Poland (15) and abroad (15). It was possible to maintain an equal gender division—50% women and 50% men. Experts with 10 to 20 years of job experience (63%) had the largest share in the sample, but there were also a lot of experts with 21–30 years of job experience (23%). Representatives of the world of science who hold the academic title of professor (22 experts, 73%) and doctor (8 doctors, 27%) were selected for the study. Experts with documented scientific achievements in the area of logistics, and above all, supply chains were selected. A very high expert level manifests itself in a very high substantive experience, qualitatively significantly exceeding the knowledge and experience of formally educated people, referred to as 43% of experts, the so-called top experts. On the other hand, 20% of experts indicated a high expert level.

The third stage was collecting experts’ opinions using the indicated heuristic method. The Delphi study consisted of two Delphi rounds and a debriefing round. The first-round questionnaire contained mainly open questions. The questions concerned the identification of key trends in supply chains and identifying critical problems that arise in modern supply chains. The questions also concerned determining how enterprises respond to disruptions in the supply chain, and how actively they strengthen their reliability (reduce future disruptions). The analysis of the open statements of the experts allowed for the development of the Delphi questionnaire for the second round. Experts were asked to indicate the significance of the identified trends in supply chains. The task of the experts was, among other things, to determine the importance (categorization) of the identified trends in supply chains in the context of global changes related to changes in Industry 4.0, the COVID-19 pandemic, and changes in consumer behavior. Experts were also to categorize contemporary supply chains’ weaknesses, and the methods of responding to supply chain disruptions identified in the first round. The third stage of Delphi’s research was verifying and confirming experts’ opinions. In the verification questionnaire, the trends in the supply chains were ordered according to the indications of the experts from the second round of the survey. The average and median of the respondents’ statements from the second round are also given, as well as the rank assigned by the expert. The task of the experts was to confirm or change their previous statements based on the collective results of indications provided by other experts. An important element of the third research stage was defining the benefits and barriers related to building the resilience of the supply chain. For this reason, supplementary questions were introduced in this round, detailing experts’ opinions in this area. These open-ended questions, in which the expert completed the sentence initiated by the researchers. Thanks to this, it was possible for experts to formulate their detailed opinions freely. The experts were asked to complete the statements presented below:

Implementation of the indicated supply chain trend will result in… (indicate the most crucial benefit from the given supply chain trend).

The main barrier related to implementing the indicated supply chain trend is ... (indicate the most critical barrier that should be removed for the supply chain trend to occur in the economic reality).

The time to eliminate the main barrier of the indicated supply chain trend in a system of 3 variants: “optimistic”, “pessimistic”, and “most probable” is estimated until ... (provide an estimated year over which the main barrier to a resilient supply chain will be addressed; it was also possible to indicate “never”).

Each expert estimates three variants: optimistic (shortest), pessimistic (longest), and most probable. The experts’ responses obtained in the third round are an original contribution to the presented research results.

The last stage of the research was the inference based on experts’ opinions collected in all analyzed rounds. In the interpretation of the obtained results, the authors also supported the results of the literature review. Thanks to this, it was possible to compare the convergence of the obtained results with the works of other researchers.

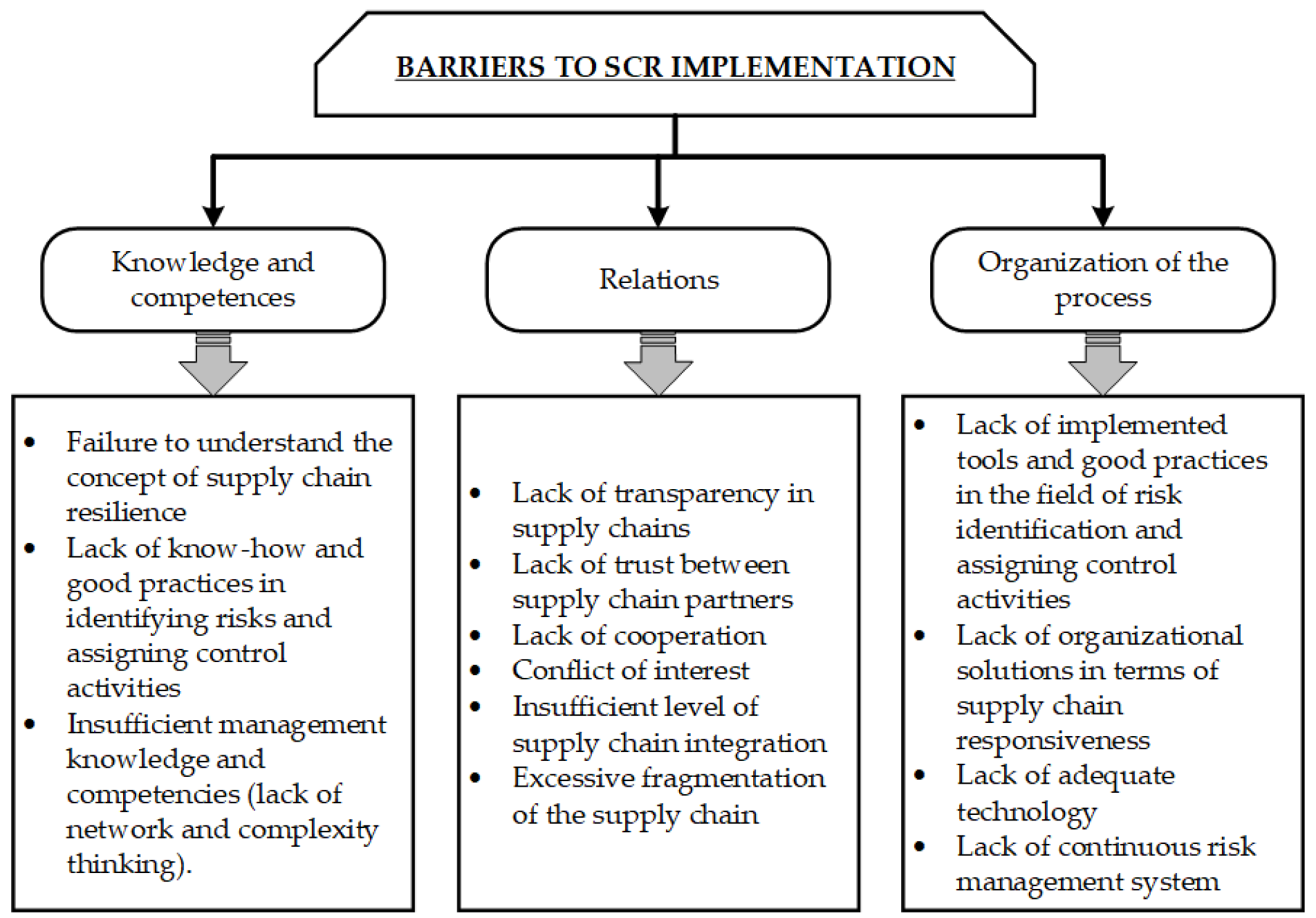

4. Results

Experts emphasize the threat posed by the VUCA environment to the Supply Chains Resilience. They are primarily distinguished by the extremely high level of turbulence further and closer to the environment and even dangerous uncertainty of events. They also detail internal barriers to realizing the SCR in reality VUCA. The analysis of the indicated barriers allowed us to distinguish three reasons for their occurrence in the supply chain: (1) related to the knowledge and managerial competencies; (2) related to the integration and cooperation of enterprises operating in the supply chain; and (3) related to the organization and technology. On this basis, the barriers identified by experts were classified. The proposed division according to the distinguished groups is presented in

Figure 5.

Based on experts’ statements for the supply chain resilience, three scenarios have been outlined: positive, most likely, and negative. The terms “positive” and “negative” refer to the speed of the estimated time of SCR implementation in the reality of VUCA after removing the most severe implementation barriers mentioned earlier.

Each of the experts indicated the time of implementing the Resilience Supply Chain in reality VUCA, after removing the most serious implementation barriers for each of the distinguished scenarios.

The positive scenario is optimistic, corresponding to fulfilling the desired changes and events in the broadly understood business environment. The negative scenario is pessimistic. Both scenarios are constructed so that it is easy to derive a realistic scenario (the most probable), i.e. a scenario of difficult adjustments to the actual situation, usually between the optimistic and the pessimistic one. Therefore, no separate scenarios are presented, although they are outlined in the conclusions.

In calculating the Resilient Supply Chain execution time, in the reality of VUCA used the following measures: first quartile (lower), median (second quartile), and third quartile (upper). They should be understood as follows:

The first quartile—according to 25% of SCR experts, in the reality of VUCA will be executed before the date corresponding to this quartile; 75% of experts said that it would be implemented after this date;

Median—according to 50% of SCR experts, in the reality of VUCA will be delivered before the median date; 50% of experts said that it would be implemented after this date

The third quartile—according to 75% of SCR experts, in the reality of VUCA will be executed before the date corresponding to this quartile; 25% of experts said that it would be implemented after this date

In the Resilient Supply Chain Execution Time explanation, in the reality of VUCA treats the median as the base measure that indicates the expected fulfillment date. The distance between the first and the third quartile informs the degree of consensus in opinions on the execution time.

Each of the 30 experts indicated the time of implementing the Resilience Supply Chain in fact VUCA for the optimistic, pessimistic, and most probable scenario.

Figure 6 considers the optimistic (fastest), pessimistic (latest), and most probable implementation time of the Supply Chain Resilience in the reality of VUCA, after removing the most serious implementation barriers. In the optimistic scenario, the median (the middle value of all experts’ responses) referred to 2026, and the dominant response was 2025. Experts showed great optimism. In the case of the pessimistic scenario, the dominant answer among experts was 2050 (according to data statistics, defined as the maximum cut-off year). The median for this scenario was 2040. Both the dominant and the median are resistant to outliers. The experts’ opinions for the most likely scenario are interesting because they relate to the same year, 2030.

The interquartile range was used to assess the differences in opinions of experts. This measure indicates opinion variability by including 50% of the middle opinions in the data series produced. On the other hand, extreme and often atypical views (also in the 50% system) are not considered. Since 50% of all opinions are by definition between the first and the third quartile, the greater the width of the interquartile range, the greater the differentiation and divergence of opinions.

The optimistic scenario is a scenario for which experts were unanimous in their statements. The interquartile range is only five years. Experts in the optimistic scenario believe that the critical implementation barriers will be removed, and the SCR level will be achieved in the reality of VUCA within the next eight years at the latest. Only three experts indicated in this scenario that the goal of attaining the SCR in the reality of VUCA would not be achieved.

In the opinion of experts on the lead time of the SCR in the reality of VUCA for the pessimistic scenario, the most significant time discrepancy was observed. Here, the value of the quartile range was 14 years. The goal will be achieved by 2048 at the latest. The extremes of opinions indicate even the year 2050. Here, as many as 27% of experts suggested that the goal of implementing the SCR will not be achieved by VUCA reality.

In the most likely scenario, the level of discrepancy in experts’ opinions about the SCR execution time was not much more significant than in the optimistic scenario. According to statistical calculations, the interquartile range is seven years, and it will be achieved by 2035 at the latest. However, the extreme opinions indicate that the goal may be completed by 2050.

5. Discussion

According to the experts participating in the Delphi study, which also confirms the authors’ opinion, one of the critical barriers to achieving a resilient supply chain is managers’ lack of understanding of resilience. Managers think it is about “mythical” resilience, but about adaptation, transformation, and the ability to overcome adversity. The resilience of supply chains determines many attitudes and relationships. Many publications [

29] emphasize that a lack of resilience can disrupt the implementation of tasks and the achievement of goals, which results in the absence of smooth cooperation of cells in the supply chain and the inability of entire chains to adapt to changes. It means that the whole supply chain (and not its part) has to be capable of counteracting the harmful effects of the immediate and further environment, market expectations, and limitations. Therefore, according to [

30], resilience can mean the ability of individual links in the supply chain and its entirety to positively develop and function well, despite objectively unfavorable business conditions. This is also how the issue is perceived by most of the experts participating in our research.

One of the significant barriers identified by experts is the lack of organizational solutions regarding supply chain responsiveness. Responsiveness, as opposed to adaptability, means change and considers the speed and accuracy of fit [

31]. At the same time, responsiveness has not been one of the most common research problems in supply chain management so far [

32], which our research results also confirmed. Meanwhile, when designing a resilient supply chain, managers should have a predetermined maximum time to perform the required operations or series of operations. Supply chain responsiveness can also improve supply chain transparency. This visibility, indicated by experts as an important barrier in building supply chain resilience, is usually understood as a possibility of obtaining and analyzing high-quality, precise, and distributed data from various sources, preferably in real time. Digital twin supply chain solutions are already known as virtual representations replicating physical objects or processes in real time (the solution is currently in the experimental phase) [

33,

34]. However, as confirmed by the results of our research, there is currently a lack of dedicated resources to support transparency supporting the building of Resilient Supply Chains in the VUCA reality.

The lack of know-how and good practices in identifying risks in the entire supply chain and assigning control activities is primarily due to the fact that managers operating in the supply chain often manage intuitively and recognize that intuitive risk management is enough. Risk management is one of the responsibilities of individual companies, but throughout the entire supply chain, its high priority is losing importance. There is also a lack of dedicated resources.

Experts participating in the study emphasize that the barrier related to Resilient Supply Chains is the lack of appropriate technological and organizational solutions related to transparency and responsiveness.

Since there is not enough know-how and good practice in risk analysis throughout the supply chain, there is also a significant gap in the ongoing risk management system in the supply chain. Risk is inherent in the organization’s activities, and brings either losses or opportunities. Therefore, effective and systemic risk management is currently one of the most critical areas of innovative activity in supply chains.

Experts in the Delphi study emphasize that a severe barrier to achieving resilient supply chains is still the lack of trust in participants in the supply chain. Distrust between supply chain partners stems from divergent cultures and environments of these links. Trust is created in the supply chain due to the compatibility of organizational cultures of individual enterprises, mutual respect, and tolerance for otherness. If it is absent or limited, this hinders the propensity to take risks throughout the supply chain and the belief that the business partner will perform actions that will bring positive results, and not take unexpected actions with negative consequences.

There is also a lack of coherent interaction in supply chains. Cooperation and competition aim to gain a better position in the supply chain. Observation of the natural world (analysis of large open systems in nature) and huge herd groups (schools of fish, ants, and herds of ungulates) show their remarkable effectiveness to the community without effective, clear leadership. What can be observed is cooperation based on the principles of collaboration and coordination: matching, imitating, and supplementing. Observation also shows the self-steering nature of this type of community: the pursuit of protection and the purpose of balance. This registers the formation of a new paradigm—organic leadership consisting in departing from individual, formal leadership, and focusing on the collective. In this case, leadership is replaced by collective interpretation and interaction processes.

Despite the cooperation of enterprises in the supply chain, a conflict of interest is also observed. It results from the interpenetration of one’s interests with the interests of other participants in the supply chain. It results from the competition, satisfying one’s needs at the expense of others, or is associated with difficulties in meeting the requirements.

There is still an insufficient level of much supply chain integration. It should be emphasized that integration is bringing together, contributing parts to the success of the whole. It is a phenomenon of uniting and harmonizing actions, aspirations, interests, and goals. Supply chain integration is a process of mutual interaction and cooperation of system elements and achieving a goal acceptable to everyone. Integration concerns both the implemented procedures and integration activities relating to harmonizing information streams and materials.

The main motive for overly fragmented supply chains is the search for often distant places of production of goods that provide low costs due to cheap labor. In the era of pandemics and geopolitical threats, global supply chains are becoming shorter, but concentrating distributed production in one place requires a thorough reconstruction of supply chains. The more complex the product, the more difficult this concentration becomes. On the other hand, however, the need to diversify will make production dispersion even more likely. This means that, as a result, globalization may become even more global. This is another critical barrier to Resilient Supply Chains.

The last-mentioned barrier, no less significant than the previous ones, is the insufficient knowledge and competencies of the management staff, including the lack of network and complex thinking. The lack of managerial competencies translates into inadequate management of supply chains, and thus creates a threatening situation.

Summing up the discussion, it is worth noting that by comparing the results obtained in the conducted research with the barriers described by other authors [

35,

36,

37], we achieve compliance in many points. The convergence of the results identifies barriers to the implementation of SCR concerns in particular:

Lack of cooperation and integration in the supply chain.

Lack of trust in the supply chain participants.

Lack of visibility and transparency.

Lack of adequate technology, in particular the lack of IT integration.

Lack of knowledge.

However, it should be noted that in the results presented in this article, much more emphasis was placed on issues related to the critical role of risk assessment and management in implementing the SCR strategy.

6. Conclusions

The current conditions for the functioning of supply chains, in reality, defined by us as VUCA, force enterprises to change their approach to managing their resources. Process efficiency aspects are still important, but managers are emphasizing the need to build the resilience of the entire supply system. Hence the growing interest of researchers and practitioners in developing SCR strategies.

The research presented in the article is initial research. For this reason, the aim of the analysis was a literature review aimed at defining the concept of Supply Chain Resilience and identifying barriers related to the implementation of the SCR strategy based on expert research. Identifying barriers is the first step to correctly defining guidelines for implementing a resilience strategy. Recognizing and understanding them will allow managers to prepare the company better to build SCR and operate in VUCA reality. The identified barriers have been grouped according to the distinguished classes. Thanks to this, it will be possible to implement comprehensive solutions consistent with the indicated source of the occurring threat. It should also be emphasized that the results obtained by us in the interviews conducted using the Delphi method are consistent with the results published by other researchers worldwide. This confirms the correctness of the conclusions formulated in the discussion. It is planned to conduct similar research among expert practitioners with extensive practical experience in supply chain management.

Further research directions will attempt to answer the following questions: (1) what influences the resilience of supply chains?; (2) can the level of resilience of supply chains be changed?; and (3) is it possible to measure the resilience of supply chains? Thanks to obtaining answers to such research questions, it will be possible to build a model of sustainable resilience of supply chains, which would take into account:

Mechanism of reducing adverse effects and the ability to overcome adversities;

Mechanism of reducing the negative chain of reactions in the supply chain so that the adverse effects do not perpetuate;

Mechanism of strengthening positive models; and

A mechanism for opening up to new possibilities.

Such a model would support managerial decisions in individual links of the supply chain, and at the same time, would indicate the directions of necessary changes resulting from the current conditions in local and global markets.