Abstract

The hotel industry has historically suffered from a misalignment of IT and business strategies, and yet has embraced digital technologies in many aspects of its operations in recent years. This article explores and assesses the options and dilemmas facing the hotel industry in selecting and implementing information systems and digital technologies as part of an evolving IT strategy. The methodology centres on a narrative synthesis of pertinent academic literature and industry source material available on the internet. Earl’s model of IT strategy development is also used as a frame of reference to assess the options facing the industry in the digital era. The article finds that some of the digital technologies have been widely deployed in the hotel sector, and an increasing number of software packages are also now available, some of which provide the requisite functionality to allow a one-stop purchase ensuring systems integration. Other packages rely more on the use of third-party software products to provide integration of different packages and digital technology applications. Findings suggest that three perspectives need to be pursued together in a balanced fashion to develop an effective overall IT strategy—top-down technology integration, bottom-up evaluation of required functionality and digital technology options—along with the inside-out matching of these needs with what is available in the marketplace. The article provides new perspectives on developing and applying IT strategy in the hotel sector in the digital era and suggests that proven approaches to IT strategy development are still of value in the planning and management of digital transformation initiatives.

1. Introduction

While the hotel industry is very diverse, encompassing large multinational chains and many small-scale independent operators, it also exhibits marked elements of concentration in that a relatively small number of large companies are often seen as the dominant players within the industry. At the same time, it is important to recognise the dynamic nature of the industry as hotels increasingly adapt to the digital revolution, and here online comparison sites have intensified price competition and increased occupancy levels. At the global scale, the structure of the hotel industry comprises three main elements, namely, brands, owners and operators. Brand companies, which include Marriott International, Hilton Worldwide, Accor and the International Hotel Group, do not operate their own hotels, but franchise the brand to hotel owners, though the brand owners set the standards for the hotels, look to control the consistency and quality of the guest experience and offer booking platforms. The owners are often real estate investment trusts that use investors’ finance to buy the hotel estate and buildings. Many of the operators are hotel management companies that operate a number of hotels, often under different brand names.

As digitalisation sweeps through industry and society at large, these hotel companies are faced with a range of challenges in developing and implementing their IT strategies. Digital technologies enable immense amounts of data to be compressed and stored in small devices, and to be transmitted at very high speeds. Accenture [1] (p. 10), the multinational professional services company, have suggested, “digital innovation and the rapid adoption of new technologies are changing everything—the way people work, how they live—and what the future will look like”. This has enabled hotel operators to seek new competitive advantages through deployment of these technologies. Many see this as constituting a “digital transformation”, which Vial [2] (p. 118) sees as “a process that aims to improve an entity by triggering significant changes to its properties through combinations of information, computing, communication, and connectivity technologies”.

In the business environment, digitalisation and digital transformation are broad concepts involving new people skills and competencies, the remodelling of business processes, and in some cases the adoption of new business models, but there are differing views and experiences regarding the role of IT strategy in guiding these change processes. Many hotel operators have hitherto based their IT strategy around specialised software packages for the hotel industry, many of which have their origins in the advent of the personal computer in the 1980s and the ensuing development of software systems for different industry sectors. The majority of these packages for the hotel industry—often badged as “Property Management Systems”—are now available via the Cloud and offer a range of functions and features. At the same time, major vendors of integrated business software (often termed “Enterprise Resource Planning” systems) for other business sectors have now customised their product offerings to make them more amenable to the hotel industry. Now, however, the increased availability and deployment of digital technologies has compounded the challenge facing hotel operators, as they search for the best strategy to guide their investment in new systems and technologies in the digital era.

Many of the existing studies on digitalisation in the hotel sector focus on the deployment of specific technologies, but little research has been undertaken on how these digital transformation projects need to be part of an overarching IT strategy and integrated with existing information systems. This article reflects upon the key issues related to this challenge, and examines the trade-offs between systems integration, required functionality, and the benefits of an increasingly wide range of digital technology applications. The paper includes this brief introduction, a section on the research method, a review of relevant literature, a discussion of the main findings in the context of two main research questions, some discussion of these findings, and a concluding section which notes the implications for theory and practice and suggests further areas for research in this field of study.

2. Research Method

The research method was inductive and qualitative, and adopted an interpretivist paradigm. The authors reviewed recently published academic literature and information obtained from various research articles on Science Direct, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. In addition, web reports and blogs from hotel industry bodies and software vendors were also reviewed. Searches were undertaken on Google using the terms “IT strategy”, “digitalisation”, “digital transformation” and individual digital technology names, in combination with “hotel industry” and “hospitality”. This provided the material for a narrative synthesis, which Popay et al. [3] (p. 5) suggest allows a “synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarise and explain the findings of the synthesis”, and which “adopts a textual approach to the process of synthesis to ‘tell the story’ of the findings from the included studies”. In all, 75 sources were reviewed, of which two-thirds were academic papers, the other third being consultancy reports or web blogs. From this review a number of themes emerged that provided the basis for addressing the research questions noted below.

The authors believe this is an appropriate approach for an exploratory paper which looks to offer some critical analysis of how digitalization is impacting the development and implementation of IT strategy in the hotel sector. Framework analysis [4] was used to analyse the content of located materials and identify emergent themes and perspectives. This process involved the construction of a simple two-dimension framework to classify sources and pertinent quotations, comprising the main digital technologies on one (x) axis and key emergent themes relating to IT strategy on the other (y) axis (Table 1). These included strategy development and alignment, systems integration, digital technology connectivity, data quality/management, people skills requirements and process change. The x axis also included a “catch-all” column for sources concerning digital transformation or digitalization in general. This allowed a synthesis of findings, with relevant materials being coded to aid in the analysis. This was an iterative, cyclical process involving identification of the emergent themes and “reflective memoing and diagramming to ensure valid integration, interpretation, and synthesis of findings” [5] (p. 341).

Table 1.

Outline framework used for classifying source material and emerging themes.

All the material identified in these searches is in the public domain and the authors judged it not necessary to seek permission to use appropriate quotations from these sources.

3. Literature Review

Some 40 years ago Sheldon [6] explored the application of front office information processing systems, such as reservations, guest accounting and room management systems, and their impact on the efficiency of operations within the hotel sector, and research in this field has grown rapidly since then. The aim of this literature review is to provide a flavour of this work, to set an academic context and a point of reference for the current paper, rather than a comprehensive identification and examination of research in the field. David, Grabski, and Kasavana. [7] (p. 64) drew attention to what they described as “the productivity paradox of hotel-industry technology”, arguing that “despite immense investment by hotel operators in information technology, evidence of improved productivity is scant, leading to discussion of a productivity paradox”.

Siguaw, Enz and Namasivayam [8] (p. 192) recognised that the use of information technology within the hospitality industry is driven by the desire to refine customer service, improve operations, minimise costs, and generate competitive advantage, but claimed that the “the degree to which the hospitality industry has embraced technological innovations appears equivocal”, in that while some researchers claim that the adoption of technology within the hospitality industry is extensive, others maintain that the hotel industry lags behind other sectors of the economy. In conclusion, the authors emphasised that the importance of aligning information technology choices with the strategic objectives of a hotel will increase in importance as hospitality executives search for additional mechanisms to obtain competitive advantage, and that employing information technology was a promising area for future development and competitive positioning.

More specifically, Law and Jogaratnam [9] (p. 170) claimed that not only had the hotel industry been criticised for being reluctant to make “full use” of information technology, but that “information technology applications in the hotel industry have largely been devoted to the handling of the routine operational problems that crop up while running a hotel”. In a wider review of global strategies within the hotel industry Whitla, Walters and Davies [10] (p. 277) suggested “opportunities for greater integration and concentration of back-office functions, where information-based systems allow for cost economies and enhanced coordination, often remain relatively unexploited, primarily due to institutionalized management practice and control constraints”.

Today, the dominant information systems used across the hotel industry are the Property Management Systems (PMS), packaged software products available from a wide range of suppliers, some of which operate globally. In addition, major vendors of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems—including SAP, Oracle, Infor, and Epicor—are now selling their products into the tourism and hospitality industry. Protel [11] (para. 3), one of many PMS vendors, emphasise the potential of advanced PMS, asserting that “today PMS capabilities have expanded beyond core functions like room inventory, reservations, housekeeping and room assignments, to include all areas of hotel operations. Now you can also schedule preventive maintenance, draw up room attendant sheets for housekeeping and even manage your meeting, conference and banqueting rooms”. These systems—both PMS and ERP—will normally have a detailed customer (or “guest”) database and provide functionality that may include some or all of the following: automated pre- and post- stay communication with guests, managing hotel room bookings, co-ordination with channel managers to improve room occupancy, payments processing to accommodate credit card transactions in compliance with regulatory standards, tax and fees calculation capability, compliance with government reporting regulations, and day-to-day operations such guest check-in/check-out, updating room rates, and managing housekeeping tasks. There are a number of recent third—party reports available that detail the respective pros and cons of these systems for different types of hotel operators—hotel chains, independent city hotels, small hotels, etc. [12,13,14].

There has been a widespread recognition that “the digital revolution has dramatically changed the operation and management of hotels, and digital technologies have been recognised as the primary sources of efficiency and competitive advantage in the hotel sector” [15] (para. 1). Digitalisation has added another layer of technology complexity, requiring a re-consideration of overall IT strategy. Smith [16] (para. 1) recently observed that “businesses of all shapes and sizes and across all industries are undergoing an aggressive transformation as they compete in an increasingly digitized world”. Smith also noted that “to address these challenges, many organizations must reassess their IT strategy to ensure their infrastructure supports and enables digital transformation”. The challenges are multi-faceted. On the one hand, customer expectations regarding digital technology innovations pressure hotel operators to implement a range of new devices and technologies that aim to provide better customer service and generally improve operational efficiencies. Li et al. [17] (p. 1) note, “because of their advantages in labour cost reduction and service efficiency, intelligent technologies have been infused into the hospitality and tourism industry, from underlying technologies such as Internet of Things (IoT), big data, cloud computing, speech recognition, and facial recognition to various applications such as social media, virtual reality (VR)/augmented reality (AR), intelligent service desks, and service robots”. Collectively, these technologies are often termed “smart tourism” applications, which are now embedded and spreading within the hospitality sector. On the other hand, these technologies will capture and record data that need to be stored in existing information systems, presenting “one view of the truth”. The need for integrated back-office systems in a digitised world is illustrated by the hotel customer supply chain. Lam and Law [18] (p. 63) note “a customer journey is more complex in the current experience era of mobile connectivity, with the property stay being just one stage in a seven-stage customer journey consisting of Dream, Select, Book, Prepare, Stay, Share, and Come Back”. All these stages use customer data that should be held in a centralised back-office database that can provide consistent and timely data at each stage of the journey, essential for an efficient and linked process. The authors note “failure to manage every stage properly has exposed hotels to competitive forces that have diluted share and profitability”.

There are clear parallels here with the 1980s and 1990s. Then, the introduction of the personal computer and local area networks required a re-assessment of data recording and processing activities in the big hotel chains, but also offered smaller operators the chance to automate their hitherto largely manual systems. Standalone customer data bases, spreadsheets for financial accounting, and new hotel specific software packages were implemented by the more tech-savvy hotel owners. The advent of the internet and its widespread availability across society from the 1990s onwards provided new ways of finding customers via on-line travel agencies, social media and email, but as new systems were implemented in one-off projects in hotel companies, the risk of diverse non-integrated, non-controlled and non-managed systems rapidly grew, and hampered the provision of reliable management information. Buhalis [19] (p. 409) noted at the time that “unless the current tourism industry improves its competitiveness, by utilizing the emerging ITs and innovative management methods, there is a danger for exogenous players to enter the marketplace, jeopardizing the position of the existing ones. Only creative and innovative suppliers will be able to survive the competition in the new millennium”. More specifically, Buhalis and Main [20] (p. 198), in their study of hotel operations in Wales, the French Alps and the Greek islands, concluded that small and medium hospitality organisations (SMHOs) were “often marginalized from the mainstream tourism industry, owing to their inability and reluctance to utilize information technologies (ITs)”. Now, more than two decades later, with Cloud computing, the IoT, analytics, big data, and robotics, the risks are similar and arguably on a greater scale.

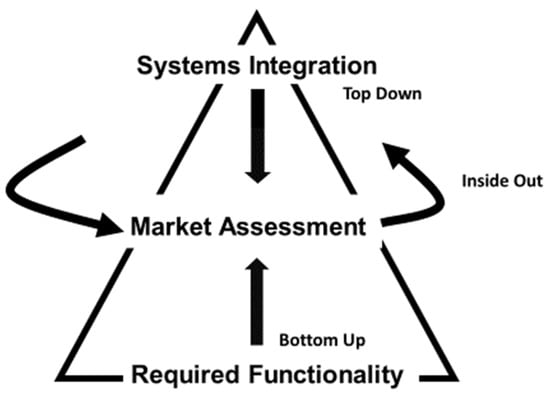

A number of IT models were considered as possible theoretical frameworks within which to set the findings. The TOE model [21] and the UTAUT model [22] have been used in many research studies that examine technology adoption [23,24,25]. Other models [26,27] have been used to assess technology implementation, focusing on specific elements of change—the technology itself, but also business processes (which are often reengineered as a result of technology implementation), people skills and competencies (which are impacted both by the new technologies and the resultant changes in working practices), and structural change. These concepts are also evident in a number of models that seek to align IT strategy with overall business strategy [28,29]. Earl [30] took a somewhat different approach to the development and implementation of IT strategy, identifying three main ways in which IT strategy could be developed and implemented in line with business strategy, these being “top-down”, “bottom-up”, and “inside-out”. Although some see his three possible strategies as alternatives, Earl in fact argued that all three can be used in parallel and that different strategies may be more appropriate in different business contexts as organisations evolve. The top-down approach represents a more formal attempt to match IT investment with business needs. It looks at the “big picture”, identifies the business plans and goals, and then applies an analytical approach to determine IT requirements in the mid to long term. The bottom-up approach is more tactical and starts from an evaluation of the capabilities of IT currently in place and may lead to a number of smaller scale projects to deliver tangible business benefits within a shorter timescale. The inside-out approach will look at recent developments in the technology marketplace and how competitors are exploiting them. It will attempt to identify opportunities afforded by new technologies which may yield competitive advantage. Elements of these frameworks, and notably Earl’s IT strategy development model, are used to assess some of the IT choices currently confronting hotel operators.

Building upon the above review of relevant literature, this article now addresses two main research questions (RQs). Firstly, how are digital technologies being deployed in the hotel industry? Secondly, what are the implications for the development of IT strategy in the hotel industry?

4. Findings

4.1. RQ1. How Are Digital Technologies Being Deployed in the Hotel Industry?

The growth of the digital economy has enabled companies in the hotel sector to seek new competitive advantages within the digital landscape and to drive growth. Limna [31] (p. 2) notes “the hospitality and tourism industry is leveraging cutting edge technologies, such as artificial intelligence and robotics (AIR), to enhance customer service and experience. These technological advancements have been transformed into smart tools for providing customer service, and they are being used to improve the customer experience”. These technologies are constantly evolving, but the two acronyms of SMAC (social media, mobile, analytics/big data, Cloud) and BRAID (blockchain, robotics, artificial intelligence, Internet of Things and digital fabrication, which encompasses augmented and virtual reality applications) are often used as umbrella terms in this context. The ways in which these technologies are being used in the hotel industry differs from property to property, depending on size and complexity of the operation and the existing technology infrastructure. For example, in branded hotel companies, strategy tends to be developed by the corporate office of the hotel management company and implemented by the properties under management. In other hotel groups, individual properties are given more freedom to select and implement their own technologies.

Of all the digital technologies, Cloud computing has arguably had the greatest impact in the hotel industry, and also acted as a catalyst for the use of other cloud-based digital technologies, as the mainstream information systems have been migrated to the Cloud. The vast majority of PMS and ERP packages for the hotel industry are now available in the Cloud. The Epicor iScala ERP product for the hospitality sector, for example, aims to efficiently integrate all of the hotel’s operations, and has four main “suites” (Financials, Supply Chain Management, Human Capital Management and Service), but also an Integration module to provide connectivity with other third-party systems available in the Cloud. Epicor claim that their software “can deliver globally innovative solutions that can streamline your operations whether your organization is a hotel, resort, casino or a government lodging agency” [32] (p. 2). Other technologies and systems, such as standalone Point-of Sale (POS) applications are also widely available in the Cloud and can be linked to other systems by Application Program Interfaces (APIs), which are discussed in more detail below.

Mobile technology has also had a major influence on how the core information systems for the hotel industry have been developed and deployed and are often central to what is often termed “smart hospitality”. Mobile apps have been incorporated into these systems so that some of the functions can be executed remotely, allowing data capture and retrieval from mobiles, for both staff and customers. Applications are numerous, but the mobile check-in/check-out function is one of the most used. For example, the Oracle OPERA system for the hotel industry [33]—to minimise wait times at check-in—is equipped with a mobile version of the software which allows staff to check-in guests via any smartphone or tablet. The mobile platform also allows for reservation management, room status monitoring, task sheet management, room maintenance, and real-time updates on rooms and maintenance requests. Some of the larger hotel groups have developed their own branded mobile apps. These include Wyndham Hotels & Resorts who have launched a Road Trip Planner, an interactive booking tool that lets travellers organise a road trip and book their hotels along the way in a single transaction. Similarly, the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Lake Tahoe in the USA launched its branded mobile app to provide a range of customer services, including mobile check-in and messaging, and the captured check-in data are automatically recorded in the hotel’s main back-end information systems for validation, billing and financial accounting [34]. Another example is the provision of guest access to reserved parking by using a smart hotel app that can be downloaded to customer smartphones [35].

As in many other industries, the use of social media (Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, etc.) for marketing and communication is now commonplace in the hotel sector. This has complemented the other web-based means of communication used by the sales or channel management. Tanković, Bilić, and Sohor, [36] (p. 2), in their recent study of the role of social networks in tourist destination choice concluded that “the use of social media is having an increasingly positive impact on tourism activities and the information available on social networks”. For example, customer enquiries and order confirmation may come from online travel agencies (such as Expedia, LastMinute.com, Booking.com), with onward communication with customers being conducted via social media or email. Integration of these communication channels with the core hotel information systems is also a feature of many PMSs. Somewhat similarly, the Internet of Things (IoT) is used widely in hotels for security applications, and heat, light and humidity monitoring as it is in many other industrial and domestic environments. However, it is increasingly being used in conjunction with mobile devices and analytics for preventative maintenance and process improvements that enhance guest experiences. The vast amount of new data that IoT devices generate raises issues of storage, security and network capacity that need assessment and management. Analytics have also been used within some hotel information systems, often displaying key metrics in the form of a dashboard, indicating, for example, the room statuses, reservations, housekeeping duties, and maintenance management statistics. Analytics can also be used to report on profitability, and support marketing and advertising campaigns aimed specifically at target audiences.

Other digital technologies are more likely to be in evidence in the larger chains where there is generally more investment in IT, and greater expertise and knowledge. Artificial intelligence may be used in conjunction with analytics and big data to provide market intelligence, for example. Augmented and virtual reality are used for marketing purposes, providing virtual tours, and also for in-room entertainment. Chatbots are already in use for hotel booking functions and are likely to feature more in hotel environments as their functionality and sophistication is developed, costs reduce and the business case for such investment strengthens. Robots that automate hotel room service are also in evidence—combining with IoT sensors and artificial intelligence—to operate elevators, for example, and make room deliveries quickly and reliably [37,38]. Limna [31] (p. 1) notes “AI technologies are increasingly being used as digital assistants. They help businesses in the hospitality industry in a variety of ways, including improving customer service, expanding operational capability, and lowering costs”. Digital twins are also increasingly deployed in the hotel sector, being “virtual models of real-world objects, such as hotel rooms, floor plans, and equipment assets. They’re frequently paired with IoT data to provide real-time insight, which benefits both guests and property managers” [39] (para. 2). Blockchain technology permanently records transactions in an open, encrypted ledger and is a means of moving information in a highly secure manner. Its applications in the hotel industry are numerous and it has the potential to make a significant impact on the industry’s structure in future years. “The goals of blockchain technology in the hospitality/hotel industry is eliminating third-party costs, and encouraging direct provider to consumer interaction” [40] (para. 3). This will help minimise the role of the middlemen like the online travel agencies and also aid security in payment settlement, thereby reducing the risk of fraud. Self-sovereign identity (SSI) systems are a blockchain application of particular value to hotel guests [41]. Most SSI systems are decentralised, whereby the guest credentials are managed using crypto wallets and verified using public-key cryptography stored in a distributed ledger. Guest credentials may come from a range of data sources—for example their social media account or e-commerce purchase transaction records. Guests can grant and revoke their credentials at any given time. When a hotel requires that information, it must request it from the guest.

In summary, the digital technologies are being increasingly used in the hotel industry in conjunction with core information systems that usually reside in the Cloud, and which provide the central database for the storage and retrieval of data generated by the transactions effected within the system and via additional digital technology applications. Some of these applications have been incorporated into the information systems packages themselves (mobile apps, analytics capabilities), but others are standalone devices and technologies which require connectivity and integration (e.g., robotics, IoT). The challenge for hotel operators is to match their evolving business requirements with the most appropriate combination of these technologies in a rapidly developing technology and business landscape.

4.2. RQ2. What Are the Implications for the Development of IT Strategy in the Hotel Industry?

The impact of digitalisation on IT strategy within the complex ownership and management structure of the hotel industry has already been significant and is likely to increase further. This has brought about a number of challenges for hotel owners in adjusting their IT strategy and making the best investment in systems and technologies in the digital era. Here, the three approaches to IT strategy development put forward by Earl [30] are used as a framework within which these challenges can be assessed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Strategic considerations for hotel systems and technology deployment.

In terms of top-down integration of systems and technologies, the advent of Cloud computing presents a dilemma. The Cloud is often seen as a more flexible, scalable and cost-effective environment than on-premises solutions, allowing round the clock access from any smart device. However, the integration of systems in a Cloud environment is often facilitated by the use of APIs, linking pieces of software that allow connectivity between specific core software packages and other third-party software products or digital devices. As systems are migrated to the Cloud, many companies must rely on APIs to provide the necessary integration to ensure a sound strategic platform to support present and future hotel operations. Such integration between packages and technologies must avoid costly reworking when upgrading to new versions of the core systems to take advantage of new functionality in the software. This is not just a technology issue, as an over-reliance on this approach to provide connectivity between a large number of software products and technologies may incur risk and constitute a significant security issue. This risk is likely to be better managed and thus more acceptable to the larger hotel operators who may be installing their systems in a number of hotels, and who have the IT knowledge and expertise to support major digitalization projects. Shiji Group, the Alibaba-backed Chinese conglomerate that operates more than 70 subsidiaries and brands, for example, have developed their own cloud-based “Enterprise Platform” which uses APIs as a key component of their PMS product. They note “with over 1200 API endpoints, a true ‘API-everything’ approach makes data easily accessible and readily available for integrations, custom applications and tailoring your system to your needs” [42] (para. 4). The system is currently being implemented in a number of chains, including Peninsula Hotels, operated by the Hongkong and Shanghai Hotels group. However, although this Cloud, platform-based, solution may come to be the standard in future years, there are clearly risks involved in terms of control, skills and knowledge requirements for the hotel IT management. Technology consultancy Altexsoft [14] note “new-generation property management systems will switch towards cloud and open API platforms, which will lead to a better connection between different modules and will sufficiently improve the speed and quality of data exchange” (para. 72), but that at present “PMSs must integrate with multiple guest service technologies, so a hotel ends up with dozens of apps, attached to a system. They are hard to manage and integrate” (para. 71). A Forrester report [43] (p. 1) also recently concluded “APIs provide a foundation for innovation and digital transformation at multiple levels—but at each, they open security holes and create privacy risks”. For the smaller operators, a cautious approach that builds upon a core integrated hotel management system from one supplier, be it located in the Cloud or on-premises, remains a sound strategic choice.

Secondly, a systematic assessment of required functionality and of the potential of digital technologies will help ensure current and future business requirements are accommodated for. This bottom-up approach will focus on the nuts and bolts of systems functionality—guest check-in/check-out; online bookings processing; payments automation; mobile data access; etc., as well as the needs for management information and analysis. This is of particular significance in the digital age, as advanced analytics can potentially provide new insights into hotel operations and efficiencies, but this requires consistency in data definitions in one standard database. Here, the well-proven techniques of business and systems requirements analysis need to be applied, because not all hotels have the same requirements or operate in the same manner. Opportunities should be sought for improving processes and ways of working, but the software must fit the needs of the business. Experience in other business sectors illustrates the perils of attempting to re-shape the way a company operates to fit the software, with resultant costly change requests, ineffective processes and low staff morale.

Thirdly, an inside-out perspective on what the market offers for different sizes and types of hotel operations will help ensure a cost-effective matching of technology capability and operational needs. Standard considerations include the number of users and sophistication of functionality and features. However, the increasing use of digital technologies highlights the significance of this aspect of strategy development. Recent examples of such new developments include the digital tipping product developed by Canary Technologies [44], which can be acquired as a stand-alone system, and which lets guests tip hotel employees at any time in between check-in and checkout. Hotel guests can also offer tips to staff by scanning QR codes strategically distributed around a property. A further example of such developments is provided by Chargerback, who have developed an app for tracking lost property in hotel environments using image recognition technology [45]. It allows speedier identification of what the item is and its subsequent recognition and claim by the hotel guest. These more sophisticated applications of digital technologies will not be appropriate for all hotels, and having too many (unwanted) features is almost as bad as not having enough. Whilst such developments are available now, of greater significance are the digital technology applications on the horizon or just coming into view—notably those relating to blockchain, robotics and artificial intelligence. Never before has the need for a “technology watch” function been of such value and importance in developing IT strategy.

These three perspectives need to be pursued together and in a balanced fashion to develop an overall strategy—the need for top-down technology integration, the bottom-up evaluation of necessary systems functionality and digital opportunities, and the inside-out matching of these needs with what is available now (and in the near future) in the technology market place.

5. Discussion

The above findings raise a number of issues worthy of further discussion. Firstly, notwithstanding the importance of getting the technology selection right, there is also a need to upgrade people skills in the use of new technologies and assess whether processes need to be smoothed or re-engineered to take advantage of technology innovations. Jackson [46] (para. 4) notes that “successful digital transformation depends on people effectively adopting new ways of working or interacting with your organization. This means your digital transformation strategy needs to go beyond just the technology to encompass the people and processes that will support it”. Successful IT deployment requires a focus on process improvements and people competencies, as well as on the technology itself. Camison [47], in his study of the hotel business in the Valencia region of Spain, found that process change may go beyond routine improvements and involve process re-engineering for some companies, and a major change in business strategy in others. As regards the people dimension, the mindset of hotel leaders is critical to effecting a change in culture and the acquisition of the requisite skillsets through training and awareness programs.

Secondly, an over-concentration on digital transformation initiatives can constitute a significant risk that may threaten business operations. McKinsey [48] (para. 3) found that “less than 30% of digital transformations succeed”, and one reason for this is that such projects often cut across existing strategies and fail to recognise the risks of doing so. A recent hotel technology report recently suggested that “hotels should break out their digital transformation into small, achievable efforts directly connected to a business outcome” and that “hotels must focus on one area of improvement at a time, rather than trying everything at once” [49] (p. 3). This assertion is reasonable in that a clear business case should be made for such investment, but such a bottom-up approach to new technology implementation should also be set within a broader framework of a top-down strategy that provides a unifying platform for such initiatives, and addresses, amongst other issues, integration and on-going maintenance. What is surprising is that the need for a top-down IT strategy as a central pillar of digital transformation is not universally recognised within the hotel industry literature. For example, in their study of the readiness of 11 hotels in Asia for digital transformation, Lam and Law [18] interviewed 15 IT and Sales and Marketing senior managers. When asked about their corporate IT strategy, 12 of the 15 interviewees said they were not aware of any, and one Sales and Marketing Director cited their company’s distribution strategy as the digital strategy. Several sources [50] suggest there are five pillars for successful digital transformation: a digital mindset, a clear definition of the company’s digital destiny, investing in digital technology capabilities, managing relevant skills and talents, and evolving the organization. All of these overlap to some degree with IT strategy development but rarely is the need for such a strategy explicitly stated in the context of digital transformation.

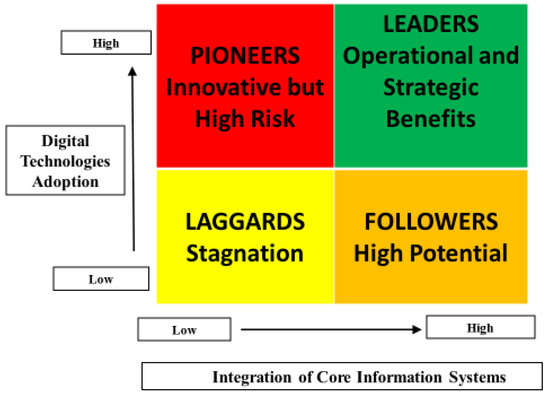

Thirdly, this review suggests that technology users in the hotel industry can be characterised as belonging to one of four different profiles, which involve a trade-off between integration and the extent of digital technology deployment (Figure 2). The Laggards, which may include some of the smaller hotel operators, still have a mix of non-integrated information systems and have made little progress in the deployment of digital technologies. Systems will probably still be located on-premises, and Epicor [51] (p. 1), typify such a technology setup as having “a strong focus on the key front-of-house activities, with traditional back-office systems needing complex tailoring to meet the unique hospitality requirements”, and that “disconnected and disjointed software solutions often require expensive, time-consuming transformation and re-keying of data in an attempt to manage and meet the needs of the business”. The Followers have progressed somewhat to have an integrated systems platform that is strategically sound, and which provides adequate management information. Systems will probably be located in the Cloud, but exploitation of other digital technologies will be limited. The Leaders, on the other hand, will have an integrated set of information systems upon which they are building a range of new digital technology systems and devices. These will probably be the larger hotel groups who have the financial and human resources to make the necessary investment. The Pioneers span the hotel ownership spectrum and are those most at risk from technology project failure and escalating maintenance costs. They have initiated a number of Cloud-based technology projects with little concern for neither overall connectivity nor data management and consistency. Their information systems are from various third parties, they are relying on APIs for connectivity, and find themselves tied into a specific Cloud platform. It is thus something of a gamble to move rapidly into this Pioneer environment in the hope and expectation that things can be sorted out as technologies are acquired and implemented. For a Laggard with only limited investment in information systems and digital technology, lessons from the past suggest that getting core integrated information systems in place as a priority is likely to provide the best results in the mid to long term. Then, the digital technology add-ons can come into play when there is a clear business case for further investment.

Figure 2.

IT profiles for hotel operators: Laggards, Pioneers, Followers and Leaders.

6. Conclusions

The deployment of information systems and digital technologies in the hotel industry is at a crossroads. There are some positive signs that software vendors are providing integrated information systems that have the functionality required by hotel operators and encompass some of the new digital technology developments that enhance data capture, processing and reporting. However, piecing together an appropriate strategy to navigate the best way through this rapidly evolving technology landscape is challenging, and hotel operators must weigh up a range of factors, including immediate cost-benefit, integration and connectivity, and current and future technology trends. Stylos et al. [52] (p. 10) point out the significance of this for many hotel operators. They note that “although the hotel industry environment is rapidly changing there are many hotels that are still using keys for their doors, paper checks, and paper vouchers” and that “hotels need to adapt to the upcoming changes by not only acquiring digital portable devices, software that allow room control, keyless entrance and smart TVs” but “structural changes in hotel management and information management across the hotel boundaries are required as well”.

As regards theoretical implications, whilst digitalisation represents a major step forward in technology development and its application in industry and society at large, the discussion to date around digital transformation strategy has been unclear and confused. “Strategy”, “initiatives”, “program”, “innovation”, “framework”, “elements” and “roadmap” have all been used by different authors in conjunction with digital transformation, sometimes interchangeably within the same text [53]. McKinsey [48], amongst others, have highlighted the importance of the people factors in developing digitalization strategy—strong backing from senior management, an empowered competent workforce, and upskilled IT staff—but these factors are nothing new and have featured in similar form in many IT strategies for decades. There is, as yet, no properly developed theory of digitalisation—neither specifically for the hotel industry nor for organisations in general—and the well-proven models and frameworks for IT strategy development and technology deployment are still of value, albeit with some accommodation of recent concepts and practices ushered in with the digital age, such as Cloud computing, platforms and ecosystems. At present, there is something of a schism between IT strategy development and the design and execution of digital transformation projects. This lack of alignment with an overarching strategy constitutes a high-risk approach that reflects the diversity of views on the essence and significance of digital transformation. This is reminiscent of the debate of 20 years ago between leading academics [54,55] about the importance of the internet—whether it was just another step in the evolution of information technologies or constituted a more fundamental paradigm change. Today, the focus is more on how to conceptualise digital transformation and whether it should be viewed as something removed from, or outside of, IT strategy, or an inherent part of it. This paper suggests that there is a disconnect between IT strategy and digital transformation in many hotel companies, that IT strategy should still provide the overarching framework for digital transformation, and that failure to do so introduces significant risk of project and strategy failure.

In terms of practical implications, this review illustrates some of the issues and dilemmas facing hotel operators in their quest to implement new systems and technologies in the digital age. Evidence suggests a degree of caution is advisable. Moving the technology environment to the Cloud has some advantages, but is not absolutely necessary, and there are also benefits to remaining in an on-premises environment. More importantly, an IT strategy—the need for which is sometimes ignored in the current literature on digital transformation—can most effectively be built around an integrated information systems core (be it a PMS, an ERP or other similar package) that has the required functionality and reporting capabilities to support hotel operations, and the connectivity features to support integration with digital technologies. Once this is in place, new technologies or systems capabilities can be piloted and implemented as appropriate within an overall technology strategy that ensures connectivity and minimises on-going maintenance overheads. Mobile apps, links to social media, business intelligence and analytics reporting are now becoming commonplace, and investment in robotics and blockchain technologies may also be good investments in due course.

Future research could develop and apply new models and frameworks for technology implementation that may be seen as part of an evolving theory of digitalization. Here, exemplar case studies by independent researchers of hotel companies that have implemented their IT strategy would be valuable in assessing the significance of some of the factors and issues raised here, notably integration and connectivity in a Cloud environment. This could also help clarify the role of IT strategy in digital transformation in the hotel industry, to establish key success factors for strategy development and provide useful guidelines for both IT practitioners and hotel operators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W.; methodology, M.W.; formal analysis, M.W.; investigation, M.W. and P.J.; resources, M.W. and P.J.; analysis, M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W. and P.J.; writing—review and editing, M.W. and P.J.; visualization, M.W.; supervision, M.W.; project administration, M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Accenture. Building A Future of Shared Success: Corporate Citizen Report 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-120/Accenture-Corporate-Citizenship-Report-2019.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Prod. ESRC Methods Programme 2006, 1, b92. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, W.; Mirza, N.; Webb, C. Using the Framework Method to Analyze Mixed-Methods Case Studies 2018; Sage research Methods Cases, Part 2; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. Use of Content Analysis to Conduct Knowledge-Building and Theory-Generating Qualitative Systematic Reviews. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J. The impact of technology on the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 1983, 4, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.S.; Grabski, S.; Kasavana, M. The Productivity Paradox of Hotel-Industry Technology. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 1996, 37, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguaw, J.A.; Enz, C.A.; Namasivayam, K. Adoption of Information Technology in U.S. hotels: Strategically Driven Objectives. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Jogaratnam, G. A study of hotel information technology applications. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitla, P.; Walters, P.G.P.; Davies, H. Global strategies in the international hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protel. (n.d.) Explore the Best Property Management System. Available online: https://www.protel.net/property-management-system/ (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- TrustRadius. Hotel Management Software. 2022. Available online: https://www.trustradius.com/hotel-management (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Hotel Tech Report. 10 Best Property Management Systems for Hotels 2022 March 19. Available online: https://hoteltechreport.com/operations/property-management-systems (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Altexsoft.com Hotel Property Management Systems: Products and Features 2019 November 27. Available online: https://www.altexsoft.com/blog/travel/hotel-property-management-systems-products-and-features/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Nilashi, M.; Tseng, M.-L.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Leung, N. Applications of disruptive digital technologies in hotel industry: A systematic review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103304. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278431922001669?casa_token=xRmSbJ6n7uIAAAAA:M7hLKtBuRVWIuCBtc8ZhB_uQdx81DWQwnnp_qxqQhjfq7FqDLT1wwm2WBfu7CGfKZAw4OnyXdCO (accessed on 3 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Cloud Storage Services Redefine How Organizations Manage File and Unstructured Data Growth and Complexity 2021, IDC Vendor Spotlight—Nasuni. NCES. IDC Research Inc.: Needham, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yin, D.; Qiu, H.; Bai, B. A systematic review of AI technology-based service encounters: Implications for hospitality and tourism operations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Law, R. Readiness of upscale and luxury-branded hotels for digital transformation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Strategic use of information technologies in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Main, H. Information technology in peripheral small and medium hospitality enterprises: Strategic analysis and critical factors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1998, 10, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePietro, R.; Wiarda, E.; Fleischer, M. The context for change: Organization, technology and environment. Processes Technol. Innov. 1990, 199, 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.; Xu, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road Ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 328–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Martins, M.F. Literature Review of Information Technology Adoption Models at Firm Level. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Eval. 2011, 14, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Awa, H.O.; Ukoha, O.; Emecheta, B.C. Using T–O–E theoretical framework to study the adoption of ERP solution. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3, 1196571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, R.; Van Belle, J.-P. Factors Influencing the Intended Adoption of Digital Transformation: A South African Case Study. Proc. Fed. Conf. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2019, 18, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R. Information Systems and Developing Countries: Failure, Success, and Local Improvisations. J. Inf. Soc. 2002, 18, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, M.; Rezaeian, M. ERP implementation in manufacturing SMEs: Lessons from the Knowledge Transfer Partnership scheme. InImpact J. Innov. Impact 2015, 8, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Peppard, J.; Campbell, B. The Co-evolution of Business/Information Systems Strategic Alignment: An Exploratory Study. J. Inf. Technol. 2014, 30, 2–43. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.C.; Venkatraman, H. Strategic alignment: Leveraging information technology for transforming organizations. IBM Syst. J. 1993, 32, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, M.J. Management Strategies for Information Technology. 1989 Business Information Technology Series; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Limna, P. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the hospitality industry: A review article. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Res. 2022, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertical Solutions. Epicor iScala for Hospitality. 2020. Available online: https://ver-solutions.com/epicor-iscala (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Hotel Tech Report Oracle OPERA PMS: What You Need to Know When Evaluating Hotel Software 2022 January 26. Available online: https://hoteltechreport.com/news/oracle-opera-pms (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Hertzfeld, E. Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Lake Tahoe Launches Branded app. Hotel Management 2022, April 7. Available online: https://www.hotelmanagement.net/tech/hard-rock-hotel-casino-lake-tahoe-launches-branded-app (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Stankov, U.; Filimonau, V.; Slivar, I. Calm ICT design in hotels: A critical review of applications and implications. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanković, A.Č.; Bilić, I.; Sohor, A. Social Networks Influence in Choosing a Tourist Destination. J. Content Community Commun. 2022, 15, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Kaushik, N.; Sivathanu, B.; Pillai, R.; Vikas, J. Consumers’ adoption of artificial intelligence and robotics in hospitality and tourism sector: Literature review and future research agenda. Tour. Rev. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, A.; Tussyadiah, P.; Stienmetz, J. Applications and Implications of Service Robots in Hospitality. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 62, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B. Digital Twins Are Changing the Hospitality Industry 2019, September 8. Available online: https://www.wrld3d.com/blog/digital-twin-are-impacting-the-hospitality-industry/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Pebbledesign. Blockchain Adds Huge New Opportunities for Hotels 2022. Available online: https://pebbledesign.com/insights/blockchain-adds-huge-new-opportunities-for-hotels/#:~:text=Blockchain%20permanently%20records%20transactions%20in,direct%20provider%20to%20consumer%20interaction (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Condatis. A New Age for Hospitality with Decentralized Identity 2021 20 September. Available online: https://condatis.com/news/blog/hospitality-decentralized-identity/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Shiji. The Hospitality Platform for the 21st Century 2020. Available online: https://enterpriseplatform.shijigroup.com/?locale=en (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Carielli, S.; Mooter, D.; Heffner, R.; DeMartine, A.; Gardner, C.; Bongarzone, M.; Dostie, P. API Insecurity: The Lurking Threat in Your Software 2021. Forrester Report. Available online: https://media.bitpipe.com/io_15x/io_159218/item_2534914/Forrester%20Report%20-%20API%20Insecurity%20The%20Lurking%20Threat%20In%20Your%20Software%20%282%29.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Canary Technologies. Canary Adds Digital Tipping to Its End-to-End Guest Management Solution to Help Hoteliers Retain Employees Amid Historic Staffing Crisis, 25 May 2022. Available online: https://www.canarytechnologies.com/press/canary-releases-digital-tipping (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Businesswire. Lost and Found Leader Chargerback Announces New Features Compatible with Apple AirTag, 23 May 2021. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210503005444/en/Lost-and-Found-Leader-Chargerback%C2%AE-Announces-New-Features-Compatible-with-Apple%C2%AE-AirTag (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Jackson, M. 5 Digital Transformation Strategies Embracing the New Normal 30 June 2020, TechTarget/SearchCIO. Available online: https://searchcio.techtarget.com/feature/5-digital-transformation-strategies-embracing-the-new-normal?src=6434693&asrc=EM_ERU_133368381&utm_medium=EM&utm_source=ERU&utm_campaign=20200817_ERU%20Transmission%20for%2008/17/2020%20(UserUniverse:%20300539)&utm_content=eru-rd2-rcpC (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Camison, C. Strategic attitudes and information technologies in the hospitality business: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 19, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey Unlocking Success in Digital Transformations. 2018. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/unlocking-success-in-digital-transformations (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Hotel Tech Report. Digital Transformation in the Hotel Industry 26 January 2022. Available online: https://hoteltechreport.com/news/digital-transformation (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Limelight. Five Pillars of Digital Transformation 2022. Available online: https://www.limelight.consulting/hub/articles/five-pillars-of-digital-transformation (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Epicor. Epicor iScala for Hospitality. n.d. Available online: https://www.intelligentcio.com/me/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2018/09/Epicor-iScala-for-Hospitality-FS-MENA-0117.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A.; Shin, D.; Huan, T.-C. Beyond smart systems adoption: Enabling diffusion and assimilation of smartness in hospitality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, M. Conclusion: Digital Transformation and IT Strategy, In Handbook of Research on Digital Transformation, Industry Use Cases, and the Impact of Disruptive Technologies; Wynn, M., Ed.; IGI-Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Strategy and the Internet. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott, D. Rethinking strategy in a networked world [or why Michael Porter is wrong about the internet]. Strategy Bus. 2001, 24, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).