Abstract

Due to its important impact on sustainable development, mobile finance spreads fast. However, what factors and how these factors impact the adoption of mobile finance apps are still unknown. This research employs UTAUT and research on mobile banking and payment to explore the adoption of mobile finance apps. A total of 348 questionnaires were collected online and offline and analyzed by SEM. The results show that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, trust, and perceived risk affect the intention to use mobile finance. This study makes theoretical contributions by contextualizing UTAUT and considering the indigenized factors in China and offers practical implications for mobile finance operators.

1. Introduction

Mobile finance, as one of the most important types of inclusive finance [1], plays significant roles in sustainable development, especially for undeveloped regions and low-income populations, which can’t obtain basic financial services that are offered usually by traditional financial institutions [2]. Mobile finance in this study is defined as individuals using apps on mobile devices to transfer out money on their electronic accounts to invest in financial products such as debt, stocks, and benefits. Compared with traditional financial services, mobile finance has many unique characteristics, such as breaking the time and space restrictions, removing the intermediary links of banks, increasing the investment channels, and lowering the investment threshold for users [3], which offer sustainable approaches to settle lots of problems that can hardly be solved in traditional ways.

Mobile finance offers users low threshold but highly customized financial service at any time and place [4], while the user can garner higher returns while maintaining asset liquidity and reduce the transaction risk that is caused by traditional financial services due to information asymmetry [5]. Therefore, the low-income population who are deprived the right of obtaining basic financial service can gain access to capital income to improve their lives by mobile finance [6]. For financial service providers, mobile finance makes it possible to collect more deal-related data, analyze the users’ credit status more accurately, offer customized service [7], and access to the long-tail users with minimal cost [8], which can enable performance sustainability in a dynamic and competitive environment. For the whole society, mobile finance improves the financial system, especially for the grass-root public [9], and eliminates income inequality [10], which can create conditions for sustainable finance [11].

Mobile finance has spread at high speed and gained many users. According to the latest report that was released by LIFTOFF and APP ANNIE, mobile finance gained the biggest rise among all kinds of mobile financial services including mobile banking, mobile payment, and mobile finance in 2021. The growth of users of the top ten mobile finance apps (measured in monthly active users or MAU) outnumbered mobile banking 5%, especially in APAC- except for China. The audience for mobile finance apps increased at least twice as fast as banking apps (https://go.appannie.com/Mobile-Finance-Report.html). The data of mobile finance users is remarkable in China. According to the financial statement that was released by ANTFIN, a subordinate to Alibaba, users of mobile finance had surpassed 730 million, and only the investment on funds had exceeded 4 trillion RMB on a fortune app in 2020 (https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H2_AN202008251401350672_1.pdf (accessed on 22 Aug 2022)).

However, what and how the characteristics of mobile finance influence its adoption are still unknown. First of all, although it is getting more attention, mobile finance is still a new phenomenon [12], and research on it is still on the surface [13]. The characteristics stimulating its fast spread have not been theorized and empirically tested. Secondly, mobile finance is, to some extent, similar to mobile banking and mobile payment [14], causing scholars to ignore its unique traits’ influence on adoption. Actually, several empirical studies on mobile financial services have shown that significant differences exist in results when they apply similar models or relatively close variables under different kinds of contexts. For example, Schierz, Schilke, and Wirtz discovered that compatibility has the greatest influence on the use of mobile payment, and mobility, subjective norms, perceived usefulness, and security play an important role, but the perceived ease of use of mobile payment influences adoption mildly [15]. However, in the context of mobile banking, perceived ease of use is one of the most critical factors [16]. Considering the context of mobile finance, we assume that the factors influencing its adoption may be different. Thirdly, the extant literature mainly employed TAM (Technology Acceptance Model) to explore factors influencing the adoption of mobile finance [13] but neglected other factors such as trust and perceived risk. Therefore, this study employs and extends UTAUT (Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology) to explore what factors and how these factors influence the adoption of mobile finance.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Firstly, we introduce the theoretical background of this study in Section 2; secondly, we present the research model and the proposed hypotheses in Section 3; and Section 4 elaborates the research methods that were used for evaluation. Then, Section 5 shows the results of empirical analysis; Finally, in Section 6, we analyze the findings of this research in-depth.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Fintech and Mobile Finance

Our study focuses on the adoption of mobile finance, which has been defined in the introduction. According to this definition, it is one of the trends of fintech. Scholars and practitioners have not reached a consensus on the definition of fintech although it has gained an amount of interest [17]. Generally, it can be viewed as a new service model of traditional finance which is transformed by technology, especially mobile internet, cloud, and data analysis [18]. Fintech has many forms in practice such as technology solutions and disruptive financial services [19].

The factors which impact the adoption and use of fintech, especially some certain forms of fintech, have been explored [20]. For example, self-efficacy and perceived usefulness promote the continuance intention of fintech [21]. Among these studies, Senyo and Osabutey’s research offers us some clues. They drew on UTAUT2 to explore the antecedents of the use of fintech innovation (mobile money) and detected the factors which affect mobile money’s use behavior [13]. However, their study deemed performance expectancy, and effort expectancy as one-dimensional constructs, which are in fact multi-dimensional constructs. Moreover, compared with the context of their study, which was sampled in Ghana, our study is conducted in China, a country with advanced IT infrastructure, so we hope to gain new insights of the adoption of mobile finance. Other factors that impact the acceptance of mobile money include trust and risk [22,23], social network [24], and some factors from TAM and other technology acceptance models [25,26]; these research hints us how to explore the factors which impact the adoption of mobile finance.

2.2. UTAUT

To explain technology acceptance better, Venkatesh et al. integrated eight theories and models to build the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), which indicates that performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI), and facilitating conditions (FC) that impact the technology acceptance, and these relationships are moderated by the user’s age, gender, experience, and voluntariness of use [27]. Evidence shows that the UTAUT is more powerful than other adoption models and theories and it can account for as much as 70 percent of the adoption [28], and its application is beyond the user adoption field. However, the UTAUT must be contextualized according to applying context [29]. So, our study builds an integrated model of the adoption of mobile finance based on UTAUT and then empirically tests it.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

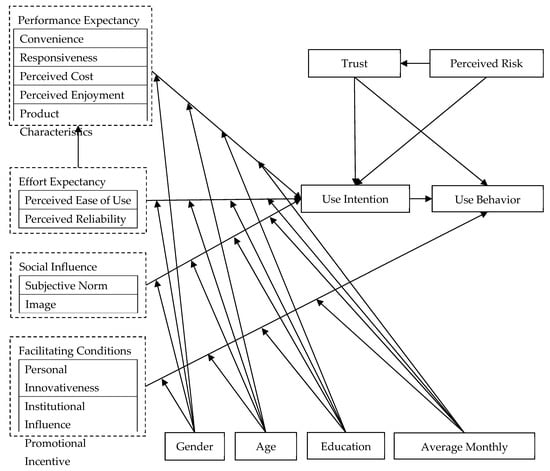

This research contextualizes four independent variables of UTAUT and adds two new variables of perceived risk and trust to detect the antecedents of the adoption of mobile finance apps. Firstly, research proves trust and perceived risk do have impacts on the user’s decision, for example, users’ decisions are influenced by their trust [30], and perceived risk affects users’ trust [31,32], thus we assume that the perceived risk and trust impact the adoption of mobile finance. Secondly, we retain the perceived ease of use as a dimension of the effort expectancy and substitute the perceived reliability for the other dimension based on the research of other mobile financial services such as mobile banking and payment [33,34] and the features of mobile finance. Thirdly, considering the Chinese context, we add personal innovativeness, institutional influence, and promotional incentive as facilitating factors [35]. According to UTAUT and the characteristics of mobile finance, we choose gender, age, education, and the average monthly income as moderators. Finally, we propose the integrated model of the adoption of mobile finance, which is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research model.

3.1. Performance Expectancy

Based on the definition of performance expectancy in UTAUT, we define it in the context of mobile finance as the extent to which users perceive using mobile finance could assist him or her to achieve better performance. The extant literature has discovered that performance expectancy can promote users’ intention to use mobile banking [30,33]. Analogously, we posit the hypothesis (H1) as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Users’ performance expectancy positively and significantly influences individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.1.1. Convenience

Convenience means that users can access mobile finance apps easily, which could save users’ time and energy to improve performance. The literature has found that the convenience of mobile apps allows users to transact anytime and anywhere [36], which has a significant impact on users’ willingness to use them [37] Therefore, we speculate that convenience promotes the adoption of mobile finance and we propose the hypothesis (H1a) as follows:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Convenience positively affects individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.1.2. Responsiveness

Responsiveness refers to responding to users’ requirements in time and providing users with detailed information and instructions for business or service [38]. Responsiveness in this study refers to the extent to which the mobile finance operators respond to the requirements and help from users, such as the velocity of sending messages and news to users, the speed of solving users’ requirements, and the transaction speed (also known as response time). Faster responsive speed is a factor that enhances users’ satisfaction to use mobile banking [39]. Mobile finance has some identical functions with mobile banking because the users have to draw money from the e-account. At the same time, in traditional investments, obtaining news and completing the transaction in a timely manner are critical which depend on responsiveness, so responsiveness may play a great role in mobile finance. As mobile finance is a technological innovation, users may encounter a lot of difficulties and generate unique requirements when using it. Whether the mobile finance operators can quickly handle the difficulties, and whether they can respond to the users’ requirements in time will impact users’ intention to use mobile finance. So, we speculate that (H1b):

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Responsiveness positively affects individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.1.3. Perceived Cost

The perceived cost is the potential cost of using mobile finance that users will perceive. Studies have confirmed that perceived cost hinders the adoption of mobile financial services [40]. For example, Wessels and Drennan found that the perceived cost negatively affects mobile banking adoption intentions [41]. To some extent, low cost means high revenue, which indicates that performance will be enhanced. Thus, we infer that adoption intentions of mobile finance will be impaired when the perceived cost is high and propose the hypothesis (H1c) as follows:

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Perceived cost negatively affects individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.1.4. Perceived Enjoyment

Perceived enjoyment is the degree of pleasure that is brought to users when using and experiencing a certain product or service, which is the perceived benefits at the psychological level. Perceived enjoyment has been proven as a crucial factor that elevates the use of mobile banking [30] and mobile payment [42]. Mobile finance apps may offer entertainment functions to users. If the potential users perceive that they could experience pleasure from using it, they will be inclined to use mobile finance. Thus, we posit the hypothesis (H1d) as follows:

Hypothesis 1d (H1d).

Perceived enjoyment positively affects individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.1.5. Product Characteristics

Product characteristics include the return rate of mobile finance, the minimum amount of investment, and fluidity. A higher return rate with high fluidity is an important trait of mobile finance, which could enhance users’ investment income. As such, we consider the product characteristics as one dimension of performance expectancy, and the analysis of reliability and validity supports this point. The investors in China pay quite some attention to the return of investment and the higher minimum amount of investment significantly abates the intention of investment. The mobile finance renounces the offline channel which reduces the operational cost, so it can provide more benefits for investors; the minimum amount of investment of mobile finance is extraordinarily low, even starting from one cent RMB, which lowers the threshold of investment; the fluidity of mobile finance is high when they invest on highly liquid assets. Therefore, we assume that (H1e):

Hypothesis 1e (H1e).

Product characteristics affect individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.2. Effort Expectancy

We define effort expectancy as the extent to which the ease of using mobile finance is expected by the potential users, including two dimensions of perceived ease of use and perceived reliability. UTAUT indicates that effort expectancy significantly affects the adoption of technology. Taking mobile banking as an example, the adoption raises dramatically when users perceive that using mobile banking does not require much effort [30]. Effort expectancy is also considered to influence the use intention indirectly through a positive influence on performance expectancy [30,43]. Therefore, we infer that effort expectancy positively influences performance expectancy and individuals’ use intention (H2, H3):

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Effort expectancy positively influences individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Effort expectancy positively influences individuals’ performance expectance.

3.2.1. Perceived Ease of Use

Based on Davis’ definition of perceived ease of use [44], we define it in the context of mobile finance as users’ subjective judgments about the ease of using mobile finance. The perceived ease of use has been empirically proven to play a crucial role in the adoption of a variety of technologies [45,46]. Therefore, when users deem that using mobile finance does not take much effort, their intention to use may be enhanced; on the contrary, their intention may be greatly reduced. Thus, we posit the hypothesis (H2a) as follows:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Perceived ease of use significantly influences individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.2.2. Perceived Reliability

The perceived reliability of mobile finance refers to the users’ subjective perception of the reliability of mobile finance [47]. High reliability allows users not to spend extra effort to solve a series of problems that are caused by the unreliable system, so we take it for one dimension of effort performance. It has been found that users’ perception of the reliability of innovative technology will significantly stimulate their use intention [48]. Studies have pointed out that perceived reliability is one of the most powerful factors impacting the acceptance of mobile banking [49]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the perceived reliability will promote users’ intention to use mobile finance (H2b):

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Perceived reliability significantly affects individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.3. Social Influence

Social influence is defined as the extent to which an individual perceives that other people who are important to him/her believe he or she ought to use the new system [27]. As individuals adjust their beliefs and behavior based on their social networks, the information that is provided by users around them can boost their use intention [50]. In the context of mobile payment, social influence has been proven to have a critical impact on the use intention [51]. Some studies have found that more exchange adopters in one’s social network increased the acceptance of mobile money [24]. Thus, we posit that (H4):

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Social influence positively influences individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.3.1. Subjective Norm

Based on Venkatesh’s definition of the subjective norm [27], we define the subjective norm as the degree to which individuals perceive that people who are important to them encourage them to use mobile finance. Subjective norm has been empirically proven as an important factor that influences the use intention [29]. Therefore, we assume that if users observe that person who has an influence on them uses mobile finance, their intention to use mobile finance will be boosted. So, we posit the hypothesis (H4a) as follows:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Subjective norm significantly influences individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.3.2. Image

Image refers to the extent of enhancement of one’s image or status in one’s social system by using innovative technology. Users’ intention to use technology will be strengthened if he or she believes that using it can improve his or her status and image [50]. Similarly, we speculate that the user’s desire to use mobile finance may be reinforced by the user’s desire to emulate and follow high fashion when he or she finds others using mobile finance. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis (H4b):

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Image significantly influences individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

3.4. Facilitating Conditions

The facilitating conditions are the extent to which individuals perceive those resources and technology facilitate the use of new systems or technologies [27], mainly including elements such as personal innovativeness, institutional influence, and promotional incentives which are proposed based on the Chinese context in this study. For example, facilitating conditions obviously influence use behavior in the context of mobile banking [52]. Therefore, we speculate that the use of mobile finance will be facilitated when users recognize that they have the skills and resources to support them to adopt mobile finance. We posit the hypothesis (H5) as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Facilitating conditions positively affect individuals’ behavior of using mobile finance.

3.4.1. Personal Innovativeness

Personal innovativeness refers to the extent to which individuals are able to accept or adopt innovative technologies and products in their social environment [53], which plays an important role in use decisions for mobile applications and mobile commerce [54]. Research has shown that personal innovativeness can boost the willingness to use fintech [55]. Thus, we hypothesize that innovation-minded users may have a stronger demand for mobile finance (H5a):

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Personal innovativeness significantly affects individuals’ behavior of using mobile finance.

3.4.2. Institutional Influence

The institutional influence mainly refers to the impact of the policies and laws on mobile finance that are issued by the government and other authoritative departments. It is found that the national financial policies and regulations have impacts on the entire market, which, in tun, affects people’s beliefs about the future of mobile finance [56]. Hence, if the government has a clear policy to regulate and promote the development of mobile finance, users’ willingness to use mobile finance may be inspired. Therefore, we posit the following hypothesis (H5b):

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Institutional influence significantly affects individuals’ behavior of using mobile finance.

3.4.3. Promotional Incentive

Promotional incentive refers to a bonus or premium a user can receive through the use of mobile finance. Mobile finance operators have successfully attracted many users by offering substantial promotional incentives to potential users, which increases their actual return. There is evidence to prove that incentives can promote the use of fintech [57]. Therefore, we assume that the promotional incentive will influence the users’ mobile finance use behavior and posit the hypothesis (H5c) as follows:

Hypothesis 5c (H5c).

Promotional incentive significantly affects individuals’ behavior of using mobile finance.

3.5. Trust

We define trust in mobile finance as the extent to which an individual believes in the mobile finance apps and their operators. Trust significantly impacts use intention and use behavior. Taking mobile payment as an example, users’ trust promotes their willingness to use it and their use behavior [58]. In the context of fintech, trust also exerts a great influence on the adoption [59,60,61]. Therefore, we speculate that in mobile finance, users’ trust positively affects their willingness and behavior of using mobile finance and propose the hypotheses (H6, H7) as follows:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Trust positively influences individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Trust positively influences individuals’ behavior of using mobile finance.

3.6. Perceived Risk

Perceived risk is the perceived uncertainty that is caused by the users cannot expect their purchase results [62]. Perceived risk is a key obstacle to preventing people from using mobile financial services [43,63,64]. For example, the higher the perceived risk of using mobile banking, the more negative the willingness to use it [65]. Only when users perceive that mobile finance is low-risk, will the willingness to use it be positive. In the meanwhile, extant literature has found that perceived risk not only reduces users’ purchase intention but also noticeably affects users’ trust [66,67]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed (H8, H9):

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Perceived risk negatively affects individuals’ intention to use mobile finance.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Perceived risk negatively affects individuals’ trust of using mobile finance.

3.7. Use Intention and Use Behavior

Use intention is the extent to which an individual is willing to act particular behavior [44,68], and use behavior refers that users turn their use intention of information technology into action and to use the technology [69]. The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) indicates that use intention is the key predictor variable of use behavior. Based on the TRA theory, we assume that the stronger the user’s willingness to use Mobile finance, the more likely it is that he or she will actually use it (H10):

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Individuals’ intention to use mobile finance positively affects their use behavior.

3.8. Moderate Variable

It has been shown that gender [51], age [51,70], education [70], and income [69] moderate the relationships between the prediction variables, use intention, and use behavior. Scholars also believe that users type moderate their willingness to use fintech and have tested this theory [71]. Therefore, according to the characteristics of users of mobile finance, we explore the moderating effects which are caused by gender, age, education, and average monthly income on the relationships which we hypothesized before:

Hypothesis 11a/b/c.

The impact of performance expectancy/effort expectancy/social influence on individuals’ intention to use mobile finance is moderated by gender.

Hypothesis 12a/b/c.

The impact of performance expectancy/effort expectancy/social influence on individuals’ intention to use mobile finance is moderated by age.

Hypothesis 13a/b/c.

The impact of performance expectancy/effort expectancy/social influence on individuals’ intention to use mobile finance is moderated by education.

Hypothesis 14a/b/c.

The impact of performance expectancy/effort expectancy/social influence on individuals’ intention to use mobile finance is moderated by average monthly income.

Hypothesis 11d/12d/13d/14d.

Gender/age/education/the average monthly income moderates the relationship between facilitating conditions and individuals’ behavior of using mobile finance.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Measurement

In order to test the proposed hypotheses, we conducted a quantitative study through a questionnaire survey. The scales in this study are pre-existing. However, to fit the research context of mobile finance, we incorporated the characteristics of mobile finance. Considering the participants are Chinese, as well as to avoid the impact of language differences, the back-translation procedure [72] was adopted to ensure the equivalence between the Chinese and English versions. The questionnaire was pilot tested with 209 subjects to examine its validity and reliability. We modified the items via the results of the pilot test, including Cronbach’s alpha value and Exploratory Factor Analysis, to form a formal scale of factors that influence the adoption of mobile finance. The formal measurements are shown in Appendix A.

4.2. Data

The questionnaire was distributed online and offline from December 2020 (offline) to July 2021 (online). The target participants in this investigation were university students, employees from government and public institutions, and enterprises. To ensure the diversity of the sample, a portion of the older and retired groups were also selected as respondents. A total of 1456 questionnaires were sent out and 405 questionnaires were collected, among which 57 were obviously perfunctory and did not meet the requirements. Finally, we obtained 348 valid questionnaires (the recovery rate was 23.9%), and 162 were collected online, the remainder were collected offline. The number of the samples meets the criterion that the minimum sample size of SEM should reach [73].

4.3. Profile of Participants

Table 1 reveals the participants’ characteristics of this investigation. A total of 52.3% of the respondents are male compared to 47.7% of the total respondents who are female, which means the gender ratio of the sample is balanced. The age of the sample in this study is mainly 31–40 years old (66.1%), most of them have a bachelor’s degree or above (93.7%). The vast majority of respondents (39.9%) have a monthly income ranging from USD 724.91–1449.82, and those (30.5%) who have a monthly income ranging from USD 1449.82–2899.64 followed. In total, the distribution of the sample is basically consistent with the characteristics of mobile finance users that was shown in the 2017 White Paper on Mobile Internet Financial users with a tremendous sample size, which indicates the sample for this research is typical.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

Furthermore, most of the participants have the behavior of using mobile finance (70.4%), and 29.6% of the respondents do not use it. More than half of the respondents use mobile finance for a short period, usually less than 5 years (56.9%), and using frequency mostly falls into the range of at least once a month or less (67.3%).

4.4. Nonresponse Bias

We employed a way of comparing the mean differences of the key variables in the questionnaires from different sources (offline (earlier) and online (later)) to evaluate the nonresponse bias [74]. Table 2 presents the results of the evaluation. The Levene variance homogeneity test results show that p-values of all of the constructs of our study are all greater than 0.05, which means a significant difference in the variance does not exist. Then, according to the t-test results of the equal variances assumed, the p-values of the t-test are greater than 0.05, meaning there is non-significant difference in the mean of samples from different sources. To sum up, there is no severe nonresponse bias in our data.

Table 2.

Non-response bias test.

4.5. Common Method Bias

Harman’s single-factor test was used to examine whether the correlation among the variables is significantly caused by a common measurement source [75]. The results show that the explanation rate of the first factor is only 37.686%, which is lower than the minimum threshold (50%) that was suggested by Mattila and Enzi [76]. If there is a serious common method bias, the correlation coefficient between the constructs will be very high (for example, it may be higher than 0.9) [77], while the highest correlation coefficient between the constructs in this study is 0.692. Thus, it can be inferred that serious common method bias does not exist.

5. Result

A structural equation model (SEM) was used to evaluate model fitness and the model. In this section, we present the results in two levels: measurement model and structural model. The features and capabilities of the analysis moment of structures (AMOS) software certainly meet the requirements of SEM analysis, so this study used it to analyze the data.

5.1. Measurement Model

According to the suggestions of Hair [73], before any other statistical analysis, the reliability of the instrument should be verified to ensure the quality of the measurement. Therefore, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted in this study to assess the reliability and validity of our scales. Cronbach’s α coefficient and composite reliability (CR) were utilized to verify the internal consistency. Hair suggested that 0.7 is the minimum threshold of composite reliability [73]. On the other hand, when the number of questions of each construct is less than 6 and Cronbach’s α coefficient is greater than 0.6, indicating that the scale is valid, and if the coefficient is greater than 0.7, means the internal consistency is good. The values of CR in Table 3 are all higher than 0.7, and for most constructs, the Cronbach’s α coefficients are greater than 0.7, which clearly meet the required threshold. Although the CR values of image and personal innovativeness are 0.680 and 0.689, they are still considered acceptable values [73]. Overall, the results support the reliability of all the constructs.

Table 3.

The results of internal consistency and construct validity.

Furthermore, convergent validity and discriminant validity were used to examine the construct validity. Convergent validity in this study was examined by the average variance extracted (AVE). According to the recommendation of Hair [73], the threshold value of AVE is 0.5. The statistical results in Table 3 show that all of the AVE values of constructs are above 0.5, within the interval that is recommended by Hair [73], thus proving the convergent validity of the measurement scales.

The discriminant validity was examined in this study by whether the correlation coefficient between each construct and other constructs is lower than the square root of its AVE. According to Fornell and Larcker [78], if the relationship that is mentioned above is satisfied, it proves that the model has discriminant validity. Table 4 shows the results. The correlations between these constructs are lower than the square root of AVE. Therefore, the results fully prove the model’s discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

5.2. Structural Model

In this section, we analyzed the hypothetical paths of the model. The model fitness needs to be examined first. Then, we present the results of the model hypothesis, describing the relationship between the structural variables and the evaluation of moderating variables. Finally, we compare and analyze the influence of different factors on the behavior of users and non-users of mobile finance.

5.2.1. Model Fitness

The Goodness of Fit (GoF), which is used to examine the fitness of the collected data and the proposed model, is essential in SEM. Our study employed maximum likelihood (ML) estimation to examine the GoF, the related indices, including the absolute fitness indices, such as χ2/df, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), and the relative fitness indices, such as CFI, NFI, NNFI, and IFI.

After the initial examination, the values of GFI and CFI do not reach the threshold (Appendix B), which means the model has to be further modified. Therefore, we utilized modification indices which is provided by AMOS to modified GoF. After the correction, χ2/df =2.532, between 1.0 and 3.0, RMSEA is within the suggested interval (<0.08). According to the research of Hair [73], the values of IFI, CFI, AGFI, and NNFI are above the minimum threshold. In conclusion, the values of these indices satisfied the threshold requirements, which proves that the model fitness meets the requirements for further data analysis. Table 5 presents the value of indicators and their recommendation threshold.

Table 5.

The fit indices values of the model.

5.2.2. Assessment of Construct Relations

In this section, the hypotheses are tested. The regression results of the path coefficient of the modified model are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

The results of the constructs model.

According to the results that are presented in Table 6, the paths for hypotheses H1, H2, H4, H6, H7, and H10 are statistically positive and significant. Consistent with previous studies, the results indicate that users’ intention to use mobile finance is significantly affected by trust, SI, EE, and PE, with SI having the greatest influence (β = 0.750). As shown in the results, the model explains 63.6% (R2) of the variance for users’ use intention. The impact of EE on PE is significant and positive (H3 is supported), which is in line with the results of Verkijika’s research [43]. The R-square of PE is 0.779, which means that 77.9% of the variance in PE is explained by EE. More concretely, if individuals perceive that using mobile finance is not difficult, their perceived usefulness will be enhanced obviously and then increase their willingness to use it. FC has a significant and positive effect on users’ mobile finance use behavior (H5 is supported), which is in line with the results of Alalwan et al.’s research [30]. Combined with other related constructs, 50.4% (R2) of the variance in use behavior can be explained by the model. The perceived risk has a statistically significant and negative effect on trust (H9 is supported), which in line with Yu’s research results [67], and explains 20.1% (R2) of the variance in trust. In addition, it is worth noting that the perceived risk affects trust strikingly, and trust influences use intention obviously, but the perceived risk affects use intention negligibly. Thus, we speculate that users’ trust in mobile finance mitigates their perception of security and financial risks, making risk indirectly affect users’ willingness to use, and H8 is not supported.

From the sub-categories of PE, the results in Table 6 show that convenience exerts a significantly positive effect on users’ willingness to use (H1a), and the product characteristics of high return, low investment threshold, and high liquidity also affect users’ intention to use mobile finance positively (H1c). When the perceived cost of using mobile finance increases, the users’ willingness to use it decreases sharply, presenting a significant and negative correlation (H1e). However, the results show that H1b and H1d are not supported. For H1b, we suspect that users’ requirements of message feedback for mobile apps may be satisfied by advanced Internet technology, so responsiveness has little impact on the adoption behavior of mobile finance. For H1d, a possible explanation is that most people are sensitive to monetary transactions and the transactions that are involved in mobile finance are usually large in amount, so the process of using mobile finance is not entertaining for the majority of people.

Furthermore, the perceived ease of use (H2a), perceived reliability (H2b), subjective norm (H4a), and image (H4b) also significantly impact users’ willingness to use mobile finance, among which subjective norm has the highest impact on users’ intention to use (β = 0.481), indicating that users are highly susceptible to being influenced by those that are close and important to them to choose to use mobile finance.

From the perspective of FC, personal innovativeness (H5a), institutional influence (H5b), and promotional incentive (H5c) all positively affect the use behavior, among which promotional incentive has the highest impact on the use behavior (β = 0.270). Since the Chinese mobile finance market is still in the cultivation and development stage, its policy impact has not drawn the mobile users’ attention, which leads the institutions to impact users’ intention mildly.

As mentioned earlier, this study uses age, education, gender, and income as moderators to explore the moderating effect. The results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

The result of moderating effect.

Gender is treated as a binary variable, so the moderating effect of gender was analyzed via the multi-group test. The results that were calculated by AMOS show that the moderating effect of gender is non-significant (H11a–H11d). In order to verify the moderating effect of age, education, and average monthly income, multiple hierarchical regression analysis was conducted by adding interaction terms to the main effect. The results that are displayed in Table 7 indicate that age does not act as a moderator between other variables and use intention or use behavior (H12a–H12d). In summary of the above results, gender and age have little moderating effect on the willingness and behavior of users to use mobile finance. These results may be due to the inclusiveness of mobile finance.

In contrast, the relationship between SI and use intention (H13c) is significantly moderated by users’ educational backgrounds, while the moderating effect between PE and use intention (H13a), EE and use intention (H13b), as well as between FC and use behavior (H13d) is non-significant. The users’ average monthly income significantly moderates the relationship between FC and use behavior (H14d) but has a non-significant moderating effect on use intention (H14a–H14c). On the whole, highly educated people are less likely to be influenced by their social relationships to use mobile finance. We speculate that this is because they can think more independently. People with high monthly income are more likely to be influenced by FC to adjust their use behavior, as they pay more attention to them.

Overall, after empirical analysis, 21 of the 38 hypotheses are examined. Table 8 presents the results of the hypothesis testing.

Table 8.

Summary of hypotheses.

5.2.3. Users Versus Non-Users

Most of the participants (70.4%) in this investigation used mobile finance, and another 29.6% did not use it. Therefore, we further investigated the different influences of different factors on users and non-users. The results are presented in Table 6.

Using AMOS to analyze the modified model, it is clear that EE, SI, PE, and trust significantly impact the use intention of two groups of people (users and non-users). Among them, PE, SI, and EE have stronger impacts on users, while trust has a stronger effect on non-users. The effect of the perceived risk on use intention is non-significant in either group. In the subdivided construct, convenience, product characteristics, image, perceived reliability, subjective norm, institutional influence, and the perceived ease of use impact both groups significantly (convenience being the highest), and they influence users who already used mobile finance more obviously. Responsiveness and perceived enjoyment negligibly affect either group.

It is also worth mentioning that FC has a significant effect on the users’ group but not a significant impact on the non-users’ group. Equally, the influence between the perceived risk and trust has different significant levels in the two groups. The increase of the perceived risk of users who already used mobile finance does not reduce their trust in mobile finance obviously, but the increase of the perceived risk of potential users who did not use mobile finance strikingly reduces their trust in mobile finance and then affects their use intention. In other words, the use intention of potential users to use mobile finance is distinctly decreased by a high perceived risk. The analysis results also show that the perceived cost directly affects the behavior of non-users, but the effect on users who already used mobile finance is indirect, which indicates that potential users may reject using mobile finance because of the high perceived cost.

Moreover, it is consistent with the reality that personal innovativeness and promotion incentives influence the behavior of users distinctly, but mildly affect the behavior of non-users. In reality, people who are more likely to try new things usually have high personal innovativeness, so they prefer to use mobile finance, while people with low innovation are less likely to try new things, such as mobile finance. Promotional incentives are more targeted at users who already used mobile finance, as it promotes their frequency of use, whereas, for those who did not use mobile finance, this method is less attractive.

6. Conclusion and Contribution

6.1. Key Findings

The objectives of this research are to explore what factors and how these factors impact the adoption of fast-spreading mobile finance. Based on the UTAUT model and Venkatesh’s [27] suggestion of contextualization according to its applied environment, we discover that performance expectancy, facilitating conditions, social influence, effort expectancy, perceived risk, and trust affect the intention to use mobile finance. However, the sub-categories of these factors present diversified impacts on the adoption of mobile finance.

Performance expectancy can be decomposed into convenience, responsiveness, perceived cost, perceived enjoyment, and product characteristics according to the characteristics of mobile finance. Convenience and product characteristics including the investment return rate can enhance the adoption of mobile finance, and perceived cost clearly declines the users’ intention to use mobile finance, while the impacts of responsiveness and perceived enjoyment on the adoption of mobile finance are not statistically significant. Effort expectancy mainly includes the perceived ease of use and perceived reliability; both can enhance the adoption of mobile finance, although their influence on use intention is marginal, compared with the sub-categories of social influence. Both the subjective norm and image in social influence, especially the subjective norm, sharply influence adoption. The facilitating conditions are contextualized as personal innovativeness, institutional influence, and promotional incentive based on the traits of mobile finance and the unique Chinese environment. Each of them has a positive influence on the behavior of using mobile finance. Trust and perceived risk are crucial factors. Trust can boost the adoption of mobile finance directly, but the perceived risk can only influence adoption through trust.

6.2. Contribution and Implication

By extending the UTAUT model, we explore the factors which impact the adoption of mobile finance in China and make the following contributions and implications.

6.2.1. Theoretical Contributions

Our study explores the factors which influence the adoption of mobile finance in the Chinese context and makes theoretical contributions as follows.

Firstly, this study empirically examines the factors which influence the adoption of other forms of mobile financial services in the context of mobile finance. Studies on the adoption of mobile payment and banking can be categorized into three streams. The first stream considers the factors (e.g., social norm, compatible) in traditional technology acceptance models, such as TAM and UTAUT, and tests their impact on the adoption of mobile payment and banking. The second stream considers the traits of mobile financial services, such as the response time of transaction and safety and tests their impact on adoption. The third stream considers the characteristics of mobile apps such as mobility and convenience and examines their impact. Our study conceives the similarities among mobile finance, mobile payment, mobile banking, and fintech to test these factors’ influence and finds that the majority of factors which influence mobile payment and banking’s adoption also influence the adoption of mobile finance. For example, convenience, which has a great impact on the adoption of mobile banking, also has a great impact on mobile finance. Our results indicate that the traditional models of technology acceptance are eligible in the environment of mobile finance on one hand and prove that the analogousness does exist among different kinds of mobile finance on the other hand.

Secondly, the literature on mobile payment and banking ignores distinctive traits of mobile finance, so this study contextualizes these factors of TAM, UTAUT, and other models and explores how these novel factors impact its adoption. Compared with traditional financial services, Mobile finance has characteristics of low initial investment volume and high return and allows users to trade and check at any time. Therefore, considering these characteristics, this study tests their influence on adoption and discovers that product characteristics play an important role. Compared with mobile banking that is operated by the bank with high credit, the operators of mobile finance include private firms with low credit. Hence, this study takes trust into account and finds how the users’ trust in the operators, the third-party guarantee companies, and other participators of mobile finance (such as the developer of mobile finance apps) impacts the adoption and use.

Thirdly, this study contextualizes the factors in the previous literature. Taking the perceived risk as an example, in the literature on mobile banking and payment, it is categorized many dimensions. For instance, perceived risk was divided into six dimensions by Stone and Gronhaug [79], which are time risk, performance risk, psychological risk, social risk, physical risk, and financial risk. However, the essence of mobile finance is an investment, which is different from mobile banking and mobile payment. Consequently, this paper divides perceived risk into three dimensions: the financial risk of users’ economy, the security risk of user information protection, and the operational risk of mobile finance, and explores the impact of perceived risk on mobile finance. However, the results show that the perceived risk indirectly affects the adoption and use of mobile finance; it mainly affects those through trust. Another example can be illustrated by the extant research which has indicated that the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness have great influences on users’ intention of using mobile payment [50]. However, as mobile finance is at a very early stage, many users are still in a wait-and-see stage so that social impact has a greater influence on users’ mobile finance behavior.

This study explores the indigenized factors in China in the context of mobile finance. The bonus is habitual promotion practice to attract potential users in China, so this study examines promotion factors’ influence and finds that the relationship between promotion and adoption of mobile finance is significant. The Chinese government formulates policies to advance inclusive finance, which is categorized into the institutional factor in this study. The result suggests that the adoption and use of mobile finance are positively affected by the institutional factor. Furthermore, we find the effect of institutions on mobile finance is less than mobile banking.

The adoption of mobile finance is moderated by many factors. The extant literature mainly focuses on the moderating effect of gender and age. This study makes a more in-depth division of the user’s demographic characteristics, detecting how factors such as education and monthly income moderate the adoption behavior. However, our results are quite different from the extant research. We only find the monthly income and education significantly moderate the relationships between the independent variables and use behavior of mobile finance. We speculate that mobile finance is one form of inclusive finance whose goal is to supply basic finance service to everyone. Thus, the individual characteristics exert little impact on the relationships between the antecedent variables and the intent to use it.

6.2.2. Practical Implications

As for the practical implications, this study helps mobile finance operators to enhance the individual’s intention to use and invest in their financing apps by optimizing the factors which trigger the intention. The majority of factors impacting the adoption of mobile finance depend on the extent of how the individual perceived them. Therefore, when designing mobile finance apps, operators should consider what kind of experience it will bring to users. Meanwhile, the traits of mobile finance and its apps play an important role in adoption, so operators should strengthen the functions and technical characteristics of mobile finance apps. For example, cost is one of the crucial factors that affects the users’ intention to use mobile finance. Reducing the transaction and use costs of mobile finance will greatly increase the use intention of potential mobile finance users. Operators can try their best to reduce cost to raise users’ willingness to use mobile finance and can also adopt price strategies to attract users.

Social influence is also a major factor that could enhance the intention to use mobile finance. Taking this as a starting point, we should reasonably choose the form of advertisement and promotion. In China, many mobile finance operators choose celebrities as their advertising-endorsers and have achieved remarkable performance.

Although mobile finance operators have introduced a series of security measures, there are still many potential users questioning the security of mobile finance. Operators should strengthen the technical security of mobile finance apps and dispel people’s worries about using mobile finance. In view of the investment nature of mobile finance, the operators should further strengthen risk control, for example, bring in the third-party guarantee system of mobile finance.

6.3. Limitation and Future Research Direction

There are several limitations in this study. First of all, we deduced the factors from UTAUT and developed the hypotheses by referring to mobile banking and payment, which may neglect other possible factors. The next step in our job is to induce the factors through in-depth interviews with the users of mobile finance. Secondly, we chose demographic variables to study the moderating effect based on UTAUT, which may ignore other moderating variables, so we will choose other behavior variables to study their moderating effect on the adoption of intention to use mobile finance in the future. Third, although mobile finance can enhance the sustainability by poverty elimination and empower people with the right to basic financial services, the mechanisms are unknown, therefore, we will assess how the mobile finance impacts the sustainability of the financial systems and economic development in the future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L., X.Z. and G.Z.; Data curation, G.L. and X.Z.; Formal analysis, G.L. and G.Z.; Funding acquisition, X.Z. and G.Z.; Methodology, G.L., X.Z. and G.Z.; Resources, G.L.; Validation, X.Z.; Writing—original draft, G.L.; Writing—review & editing, G.L., X.Z. and G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21AZD022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed in this study can be available from the corresponding author by email.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement items

Table A1.

Measurement items.

Table A1.

Measurement items.

| Constructs | Item | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | Convenience | 3 items | Hoehle et al. [37]; Mansour [36] |

| Responsiveness | 2 items | Parasuraman et al. [38]; Jun & Cai [39] | |

| Perceived Cost | 3 items | Zhou [40] | |

| Perceived Enjoyment | 2 items | Zhou [42]; Alalwan et al. [30] | |

| Product Characteristics | 3 items | These items are developed by ourselves. | |

| Effort Expectancy | Perceived Ease of Use | 3 items | Yoon & Steege [45] |

| Perceived Reliability | 3 items | Hanafizadeh et al. [48] | |

| Social Influence | Subjective Norm | 3 items | Liebana-Cabanillas [50] |

| Image | 3 items | Liebana-Cabanillas [50] | |

| Facilitating Conditions | Personal Innovativeness | 3 items | Tun-Pin et al. [55] |

| Institutional Influence | 2 items | Ammar & Ahmed [80] | |

| Promotional Incentive | 2 items | Zhao, Anong, & Zhang [81] | |

| Trust | 4 items | Wang et al. [60] | |

| Perceived Risk | 3 items | Gefen [66] | |

| Use Intention | 3 items | Venkatesh [29] | |

| Use Behavior | 2 items | Venkatesh [29] | |

Appendix B. The First Goodness of Fit Indices of the Structural Model

Table A2.

The First Goodness of Fit Indices of the Structural Model.

Table A2.

The First Goodness of Fit Indices of the Structural Model.

| Fit Indices | The Proposed Model Fit | Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| df | 344 | |

| Chi-square () | 979.594 | |

| 2.848 | <3 | |

| GFI | 0.826 | >0.9 |

| AGFI | 0.790 | >0.8 |

| NFI | 0.857 | >0.90 |

| NNFI | 0.895 | >0.90 |

| CFI | 0.890 | >0.90 |

| IFI | 0.910 | >0.90 |

| RMR | 0.119 | <0.05 |

| RMSEA | 0.075 | <0.08 |

References

- Lorenz, E.; Pommet, S. Mobile money, inclusive finance and enterprise innovativeness: An analysis of East African nations. Ind. Innov. 2020, 28, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Le, T.; Hoque, A. How does financial literacy impact on inclusive finance? Financ. Innov. 2021, 7, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanian, H.; Fischer, F. The Future of Finance: The Impact of FinTech, AI, and Crypto on Financial Services; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arslanian, H.; Fischer, F. Fintech and the Future of the Financial Ecosystem. In The Future of Finance: The Impact of FinTech, AI, and Crypto on Financial Services; Arslanian, H., Fischer, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, G.; Corrado, L. Inclusive finance for inclusive growth and development. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 24, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; He, G.; Turvey, C.G. Inclusive Finance, Farm Households Entrepreneurship, and Inclusive Rural Transformation in Rural Poverty-stricken Areas in China. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2021, 57, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G.; Hornuf, L. FinTech Business Models. In FinTech and Data Privacy in Germany: An Empirical Analysis with Policy Recommendations; Dorfleitner, G., Hornuf, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S.; Taube, M. The long tail thesis. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2019, 14, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyo, P.K.; Karanasios, S.; Gozman, D.; Baba, M. FinTech ecosystem practices shaping financial inclusion: The case of mobile money in Ghana. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 31, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiteng, Y. A Review on the Effect of Digital Inclusive Finance on Income Disparity. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Social Sciences and Economic Development (ICSSED 2022), Wuhan, China, 29 April 2022; pp. 591–594. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.; Yajuan, L.; Khan, S. Promoting China’s Inclusive Finance Through Digital Financial Services. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 23, 984–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyanto, A.; Primiana, I.; Yunizar; Azis, Y. Disruptive Technology: The Phenomenon of FinTech towards Conventional Banking in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 407, 012104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyo, P.; Osabutey, E.L. Unearthing antecedents to financial inclusion through FinTech innovations. Technovation 2020, 98, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Gu, X.; Jagtiani, J. A Survey of Fintech Research and Policy Discussion. Rev. Corp. Finance 2021, 1, 259–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierz, P.G.; Schilke, O.; Wirtz, B.W. Understanding consumer acceptance of mobile payment services: An empirical analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanyeza, C. Determinants of consumers’ intention to adopt mobile banking services in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 997–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milian, E.Z.; Spinola, M.D.M.; de Carvalho, M.M. Fintechs: A literature review and research agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 34, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomber, P.; Koch, J.-A.; Siering, M. Digital Finance and FinTech: Current research and future research directions. J. Bus. Econ. 2017, 87, 537–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, S. What have we learnt from 10 years of fintech research? A scientometric analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 155, 120022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhichao, X.; Han-Teng, L.; Chung-Lien, P.; Wenjun, M. Exploring the Research Fronts of Fintech: A Scientometric Analysis. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Financial Innovation and Economic Development (ICFIED 2020), Sanya, China, 11 March 2020; pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Daragmeh, A.; Sági, J.; Zéman, Z. Continuous Intention to Use E-Wallet in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Inte-grating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Technology Continuous Theory (TCT). J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baganzi, R.; Lau, A.K.W. Examining Trust and Risk in Mobile Money Acceptance in Uganda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Chen, C.-W.; Chen, W.-K. Drivers of Mobile Payment Acceptance in China: An Empirical Investigation. Information 2019, 10, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murendo, C.; Wollni, M.; De Brauw, A.; Mugabi, N. Social Network Effects on Mobile Money Adoption in Uganda. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 54, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mswahili, A. Factors for Acceptance and Use of Mobile Money Interoperability Services. J. Inform. 2022, 2, 1993–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Ngubelanga, A.; Duffett, R. Modeling Mobile Commerce Applications’ Antecedents of Customer Satisfaction among Millen-nials: An Extended TAM Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Zhang, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: U.S. Vs. China. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 13, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N. Factors influencing adoption of mobile banking by Jordanian bank customers: Extending UTAUT2 with trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Wamba, S.F. Blockchain adoption challenges in supply chain: An empirical investigation of the main drivers in India and the USA. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 46, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, B. Understanding perceived risks in mobile payment acceptance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Faria, M.; Thomas, M.A.; Popovič, A. Extending the understanding of mobile banking adoption: When UTAUT meets TTF and ITM. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; El-Masri, M.; Ali, M.; Serrano, A. Extending the UTAUT model to understand the customers’ acceptance and use of internet banking in Lebanon. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforet, S.; Li, X. Consumers’ attitudes towards online and mobile banking in China. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2005, 23, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, I.H.F.; Eljelly, A.M.; Abdullah, A.M. Consumers’ attitude towards e-banking services in Islamic banks: The case of Sudan. Rev. Int. Bus. Strat. 2016, 26, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehle, H.; Scornavacca, E.; Huff, S. Three decades of research on consumer adoption and utilization of electronic banking channels: A literature analysis. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, M.; Cai, S. The key determinants of Internet banking service quality: A content analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2001, 19, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. An Empirical Examination of Initial Trust in Mobile Payment. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2014, 77, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, L.; Drennan, J. An investigation of consumer acceptance of M-banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. An empirical examination of continuance intention of mobile payment services. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkijika, S.F. Factors influencing the adoption of mobile commerce applications in Cameroon. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.S.; Steege, L.M.B. Development of a quantitative model of the impact of customers’ personality and perceptions on Internet banking use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Jahanyan, S. Analyzing user perspective on the factors affecting use intention of mobile based transfer payment. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Karjaluoto, H. Mobile banking adoption: A literature review. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafizadeh, P.; Behboudi, M.; Koshksaray, A.A.; Tabar, M.J.S. Mobile-banking adoption by Iranian bank clients. Telemat. Inform. 2014, 31, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemingui, H.; Ben Lallouna, H. Resistance, motivations, trust and intention to use mobile financial services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2013, 31, 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. Antecedents of the adoption of the new mobile payment systems: The moderating effect of age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Thomas, M.; Baptista, G.; Campos, F. Mobile payment: Understanding the determinants of customer adoption and intention to recommend the technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Integrating TTF and UTAUT to explain mobile banking user adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P.; Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Raghavan, V. Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: Extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun-Pin, C.; Keng-Soon, W.C.; Yen-San, Y.; Pui-Yee, C.; Hong-Leong, J.T.; Shwu-Shing, N. An adoption of fintech service in Malaysia. South East Asia J. Contemp. Bus. 2019, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, I.H.-Y. A new era in fintech payment innovations? A perspective from the institutions and regulation of payment systems. Law Innov. Technol. 2017, 9, 190–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwogugu, M.I. Earnings Management, Fintech-Driven Incentives and Sustainable Growth: On Complex Systems, Legal and Mechanism Design Factors; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mallat, N. Exploring consumer adoption of mobile payments—A qualitative study. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyliana, M.; Fernando, E.; Surjandy, S. The Influence of Perceived Risk and Trust in Adoption of FinTech Services in Indonesia. CommIT (Commun. Inf. Technol.) J. 2019, 13, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, Z.; Hou, F.; Li, B.; Zhou, W. What determines customers’ continuance intention of FinTech? Evidence from YuEbao. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jünger, M.; Mietzner, M. Banking goes digital: The adoption of FinTech services by German households. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 34, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.A. Consumer Behavior as Risk. Marketing: Critical Perspectives on Business Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; Volume 3, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, H.-S. Understanding Benefit and Risk Framework of Fintech Adoption: Comparison of Early Adopters and Late Adopters. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2018; pp. 3864–3873. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.L.; Ooi, C.K.; Chong, J.B. Perceived Risk Factors Affect Intention to Use FinTech. J. Account. Finance Emerg. Econ. 2020, 6, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narteh, B.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Amoh, S. Customer behavioural intentions towards mobile money services adoption in Ghana. Serv. Ind. J. 2017, 37, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Shang, R.-A.; Shu, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-K. The Effects of Risk and Hedonic Value on the Intention to Purchase on Group Buying Website: The Role of Trust, Price and Conformity Intention. Univers. J. Manag. 2015, 3, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Karjaluoto, H. Mobile banking services continuous usage--case study of Finland. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 1497–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Predicting the determinants of the NFC-enabled mobile credit card acceptance: A neural networks approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 5604–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.-S. What makes users willing or hesitant to use Fintech? The moderating effect of user type. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Cross-cultural research and methodology series; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986; Volume 8, pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis: An Overview. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 904–907. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S.; Enz, C.A. The Role of Emotions in Service Encounters. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; El Sawy, O.A. From IT Leveraging Competence to Competitive Advantage in Turbulent Environments: The Case of New Product Development. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 198–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.N.; Grønhaug, K. Perceived Risk: Further Considerations for the Marketing Discipline. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Ahmed, E.M. Factors influencing Sudanese microfinance intention to adopt mobile banking. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3, 1154257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Anong, S.T.; Zhang, L. Understanding the impact of financial incentives on NFC mobile payment adoption. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1296–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).