1. Introduction

With rapid population growth, fast urbanization, increasing economic development [

1], industrial solid waste (ISW) grows rapidly along with social development and is closely related to the economy [

2,

3]. According to statistics from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, in 2019, the general ISW generated in 196 large and medium-sized cities across the country reached 1.38 billion tons, the comprehensive utilization volume was 850 million tons, the disposal volume was 310 million tons, the storage volume was 360 million tons, and the dumping and discarding volume was 42,000 tons. The comprehensive utilization of general ISW accounted for 55.9% of the total utilization, disposal, and storage, 20.4% and 23.6%, respectively. This not only occupies a lot of lands, but also poses a long-term potential threat to air, water, and soil [

4]. Despite the increasing use of waste as a renewable resource [

5], the prevention and treatment of ISW pollution have received insufficient attention due to the hysteresis of ISW’s damage to the environment [

6]. Due to the treatment of ISW as an economic activity with positive externalities, the ability of enterprises to deal with ISW is often limited. Consequently, the so-called “market failure” phenomenon will occur, then the government needs to perform its functions to solve the problem of market failure. In China, several environmental regulations have been launched to promote the treatment and prevention of pollution from ISW since the late 1990s. The implementation of the Circular Economy Promotion Law (CEPL) in 2009 is one of the important measures. Understanding the impact of specific policies and regulations on the utilization of ISW in cities is an important way to improve the management level of cities’ ISW. However, relevant studies are still scarce today.

In the past few decades, scholars’ research on ISW is mainly focused on how to reduce its pollution through technical means. By comparing four different ISW treatment methods, Nouri et al. found that a combination of landfill, incineration, and recycling is the best treatment method [

7]. Yao et al. found that the use of lightweight porous concrete as a building material can effectively reduce the impact on the environment [

8]. In addition, by comparing the different situations in Finland, France, and China, Dong et al. found that the use of gasification technology for waste-to-energy can effectively reduce the environmental impact of solid waste [

9]. Through the method of life cycle assessment, Pérez et al. found that solid waste material separation and improved recycling process can reduce its carbon footprint [

10]. Existing studies have also analyzed the effectiveness of solid waste management policies from the perspective of policy evaluation. Taking Brazil as the research object, Cetrulo et al. found that the solid waste management policy did not achieve the expected goal, which was mainly caused by the different focus of the policy [

11]. This is consistent with the research results of Periathamby et al. who used Malaysia as the research object [

12]. However, unlike Malaysia and Brazil, by analyzing the effect of China’s waste charging policy, Wu et al. found that this policy resulted in residents taking the initiative to reduce household waste at source, which in turn curbed waste generation, in other words, China’s solid waste management policy is effective [

13]. It can be seen that current studies either focus on how different treatments of ISW can prevent and reduce the pollution of ISW or on how policies and regulations can prevent the generation of solid waste, and few studies pay attention to how policy regulations can affect the utilization of ISW. In fact, solid waste and ISW are different.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to take China’s CEPL, an environmental regulation was launched to promote the treatment and prevention of pollution from ISW, as the research object and apply the difference-in-differences (DID) method and two-way fixed effects model to empirically analyze whether the CEPL has promotion effect on resource-based cities’ comprehensive utilization rate of ISW. For each city, the laws and regulations passed and implemented at the national level can be regarded as a quasi-natural experiment that satisfies the condition of homogeneity, while resource-based cities are fixed. Therefore, it is possible to identify the impact of the implementation of the CEPL on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities through the DID method. In addition, we use propensity score matching and instrumental variables to accurately identify this impact. Compared with other studies, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) Considering the CEPL as the entry point for the first time, it discusses in detail the impact of the CEPL on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities.

(2) Based on the official promotion tournament hypothesis, the specific impact mechanism of CEPL on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities is discussed considering the competition for promotion of local officials.

(3) Using a variety of robustness tests, it empirically verifies that when the resource constraint bottleneck is reached, strengthening environmental law enforcement can provide an important direction for resource-based cities to alleviate the pressure from scarcity of resources.

The rest of this paper is arranged as follows: the second section introduces the background of the CEPL, resource-based cities, and the research hypotheses; the third section introduces the data and methodology; the fourth section presents the results of empirical test; finally, the conclusions and policy recommendations are offered in the fifth section.

2. Policy Background and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Circular Economy Promotion Law (CEPL)

The idea of a circular economy originated from the spaceship theory proposed by American economist Boulding in the 1960s [

14], he advocated the establishment of a “circular economy” that does not deplete resources, does not cause environmental and ecological pollution, and can recycle various resources, instead of the “single-program economy” of the past [

15]. In the 1990s, sustainable development strategies became a global trend. Environmental protection, cleaner production, green consumption, and waste recycling began to be integrated into a systematic economic development model characterized by recycling resources and avoiding waste generation. Meanwhile, some developed countries, such as Germany and Japan, have started the legislative practice of circular economy [

16,

17,

18]. Influenced by other countries, the concept of circular economy was initially introduced into China in the 1990s [

16,

19], and often is discussed through the “3R” principles [

20], which include the reduce principle of minimizing input of production factors [

21], the reuse principle of putting fewer factors into production [

22], and the recycling principle of regarding waste materials as one of the production factors [

20]. At the same time, after nearly two decades of unprecedented growth in industrial manufacturing, China started to face a variety of pressing environmental challenges [

23], including increasing ISW. To solve this problem, Chinese policymakers had begun to consider circular economy legislation.

In 1996, the former State Planning Commission of China submitted a draft law on the comprehensive utilization of resources to the State Council, but it did not work because of different views on it. At the end of the 20th century, the Environmental and Resource Protection Committee of the National People’s Congress, influenced by foreign cleaner production legislation, began to discuss issues related to the formulation of cleaner production laws. In 1999, following the legislative plan of the Ninth National People’s Congress Standing Committee, the Environmental Resources Commission established a drafting leading group for the Cleaner Production Promotion Law and entrusted the Economic and Trade Commission of the State Council to draft the law. After 3 years, a draft was formed and submitted to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. In June 2002, this law was reviewed and passed at the 28th meeting of the Standing Committee of the Ninth National People’s Congress.

Since 2002, influenced by some developed countries’ research on waste recycling and the improvement of corresponding legal systems, scholars in China had begun to put forward proposals for the comprehensive utilization of cleaner production and resources. Further, they also considered the development of a circular economy and relative legislative work. Their perspectives received the attention of the legislature. In March 2005, President Hu Jintao clearly proposed to speed up the formulation of the CEPL, then the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress decided to include the formulation of the CEPL into a legislative plan. According to the legislative plan of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, the Environmental and Assets Supervision and Administration Commission established the CEPL drafting leading group, formally launched the CEPL legislative work. In August 2008, the Fourth Meeting of the 11th Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress deliberated and passed the CEPL, which was formally implemented on 1 January 2009.

The framework design of the CEPL is based on the main line of “reduce, reuse and recycle and resource”. In terms of reduction, CEPL specifies that reasonable programs, mining sequences, methods, and beneficiation processes should be developed to extract mineral resources, while encouraging the use of non-toxic and non-hazardous solid waste to produce construction materials. In the term of reuse, recycling, and resourcefulness, CEPL clarifies the comprehensive utilization of ISW, requiring enterprises to comprehensively utilize industrial wastes such as fly ash generated in the production process in accordance with national regulations to improve the level of waste reuse and resource utilization. In addition, if an enterprise does not have the conditions for comprehensive utilization of the waste generated in the production process, it shall provide it to qualified producers and operators for comprehensive utilization.

2.2. Resource-Based City

Resource-based cities are cities that use regional mineral and forestry resources in their leading industries. With the advent of the industrial revolution, resource-based cities have appeared on a large scale worldwide [

24]. Resource-based cities, as the major producers of industrial resources, have made great contributions to the country’s economic development and wealth accumulation. However, since the main industry is mining and processing mineral resources, more and more resource-based cities are facing serious environmental degradation problems [

25,

26,

27]. Since 1920s, some scholars have begun to focus on resource-based cities lifecycle which includes formation, development, transformation, and maturity [

28,

29]. Recently, many pieces of literature pay attention to the transformation of resource-based cities [

30]. These studies mainly involve industrial transformation methods, policies, and mechanisms of resource-based cities [

28,

29,

31]. In addition, some research concern about the sustainable development of resource-based cities [

26,

28,

31]. However, in these studies, there is a lack of literature on the recycling of the industrial solid waste in resource-based cities.

Over the past several decades, China has experienced the most rapid development of urbanization in human history [

25]. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, after Reform and Opening in 1978, China’s urbanization rate increased from 17.92% in 1978 to 63.89% in 2020, while the population increased from 0.96 billion to 1.41 billion. During this period, more than 200 resource-based cities have played a vital role in promoting China’s economic growth [

27,

31]. Simultaneously, some resource-based cities have gone from prosperity to decline [

32]. Different from other countries, China’s resource-based cities face more complex challenges [

24,

33] such as the large numbers and various types of cities [

34]. Furthermore, due to resource-dependent industries occupy a larger share of their industrial structure [

35], most resource-based cities in China cannot completely change their development models in the short term to achieve sustainable development.

To improve the long-term mechanism of sustainable development and promote the sustainable development of resource-based cities, in 2013, the State Council issued a circular of National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-based Cities (2013–2020) (NSDPRC). The circular identified 126 prefecture-level cities as resource-based cities among 334 prefecture-level cities and divided these resource-based cities into four growth types: regenerative, grow-up, growing, and recessionary. Drawing on Chen et al.’s research [

24], we show the distribution and types of all resource-based cities in

Figure 1. It can be seen from

Figure 1 that resource-based cities are mainly distributed in the central and western regions of China. Moreover, the main types of resource-based cities in the central region are grow-up, while the types of resource-based cities in the western region are more diverse, including all four types. Moreover, the resource-based cities in the northeastern region are mainly recessionary.

2.3. The Official Promotion Tournament Hypothesis

As one of the measures of environmental governance, the compulsory environmental regulations implemented by the government have gradually become the main means for local governments to complete the assessment of ecological goals in recent years. This is closely related to the transformation of the assessment indicators for the promotion of officials since China’s reform and opening up. Since the Qin Dynasty, the Chinese central government has had absolute control over the promotion and removal of local officials [

36], due to incomplete and asymmetry of information, the central government often uses key work content as a measurement indicator when considering the promotion of local officials and creates a promotion targeted yardstick competition among subnational governments, which is widely known as the official promotion tournament [

37].

Since the reform and opening up, the focus of the Chinese government has shifted to economic construction. Therefore, the gross domestic product (GDP) has become the most important indicator for evaluating the performance of local officials [

36,

38] and played an important role in the talent evaluation system [

39,

40]. Such a promotion tournament has made an enormous contribution to Chinese economic growth, making China grown rapidly in the past several decades and became the second-largest economy worldwide [

37,

41]. Chinese environmental problem is not only the result of economic growth in industrialized developing countries, but also the political issues [

42]. Since the reform of the financial system in 1994, Chinese local government tax revenue has decreased. The single official promotion tournament gradually revealed its drawbacks. When officials face competition for resources and face multiple mandatory goals in the short term, they will tend to prioritize the goals that are conducive to obtaining promotion opportunities [

43,

44,

45]. Therefore, in order to increase the opportunity for promotion, local government officials have to use limited resources to attract capital and other factors to ensure economic development, resulting in a reduction in environmental governance expenditures and environmental pollution has become the price of economic development [

37]. This not only poses a serious threat to Chinese long-term development, but also has a profound impact on the global environment. In order to cope with the increasingly serious environmental problems, the central government has begun to consider including environmental performance in the evaluation indicators for official promotion. The proportion of green indicators is increasing [

46].

In December 2005, the State Council issued the “Decision on Implementing the Scientific Outlook on Development and Further Strengthening of Environmental Protection”, which clearly stated that environmental protection should be included in the assessment of local officials and the assessment situation shall be used as the foundation for officials’ promotion. The status of environmental protection in the evaluation indicators for the promotion of officials became more important when the Chinese central authority began to include emission reduction performance as an important part of the promotion assessment system for local officials in 2007 [

37]. In 2011, the State Council issued the “Measures for the Assessment of the Total Emissions of Major Pollutants”, which implemented the accountability system and the “one-vote veto” system for areas that did not meet the environmental protection assessment standards, and further strengthened the assessment of the performance of local governments in the emission reduction of pollutants. It reshapes the contribution of economic benefits to the officials’ promotion [

47,

48,

49] and makes officials balance the relationship between economic development and environmental protection [

50]. This direct incentive way can improve the environment [

51].

However, in 2009, when the CEPL was promulgated and took effect, environmental protection had already had a certain status in the promotion and assessment of officials, and local governments would actively promote the implementation of the CEPL. As for resource-based cities, since the main industries are developed based on the mining and processing of minerals, related ISW are generated more than non-resource-based cities and environmental problems are more prominent than other cities, so when the CEPL was promulgated, officials in resource-based cities were more willing to strengthen law enforcement, resulting in the CEPL’s promotion of the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities significantly higher than other cities. In addition, when the original environmental regulation intensity of a resource-based city is relatively high, the implementation of the CEPL will be favorable. The higher the intensity of environmental regulation, the more obvious the promotion of the CEPL on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in the city.

5. Conclusions

Improving the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW not only reduces environmental pollution, but also promotes the recycling of resources and ease the pressure on resources. This paper argues that the improvement of the comprehensive utilization rate of urban ISW can be achieved through the implementation of environmental policies and regulations. Using panel data of 278 prefecture-level cities in China from 2003 to 2015, this paper confirms the above view by building a DID model to analyze the impact that the implementation of CEPL would have on the comprehensive ISW utilization rate of resource-based cities. In addition, this paper also conducts a deeper analysis and obtains three main conclusions as follows.

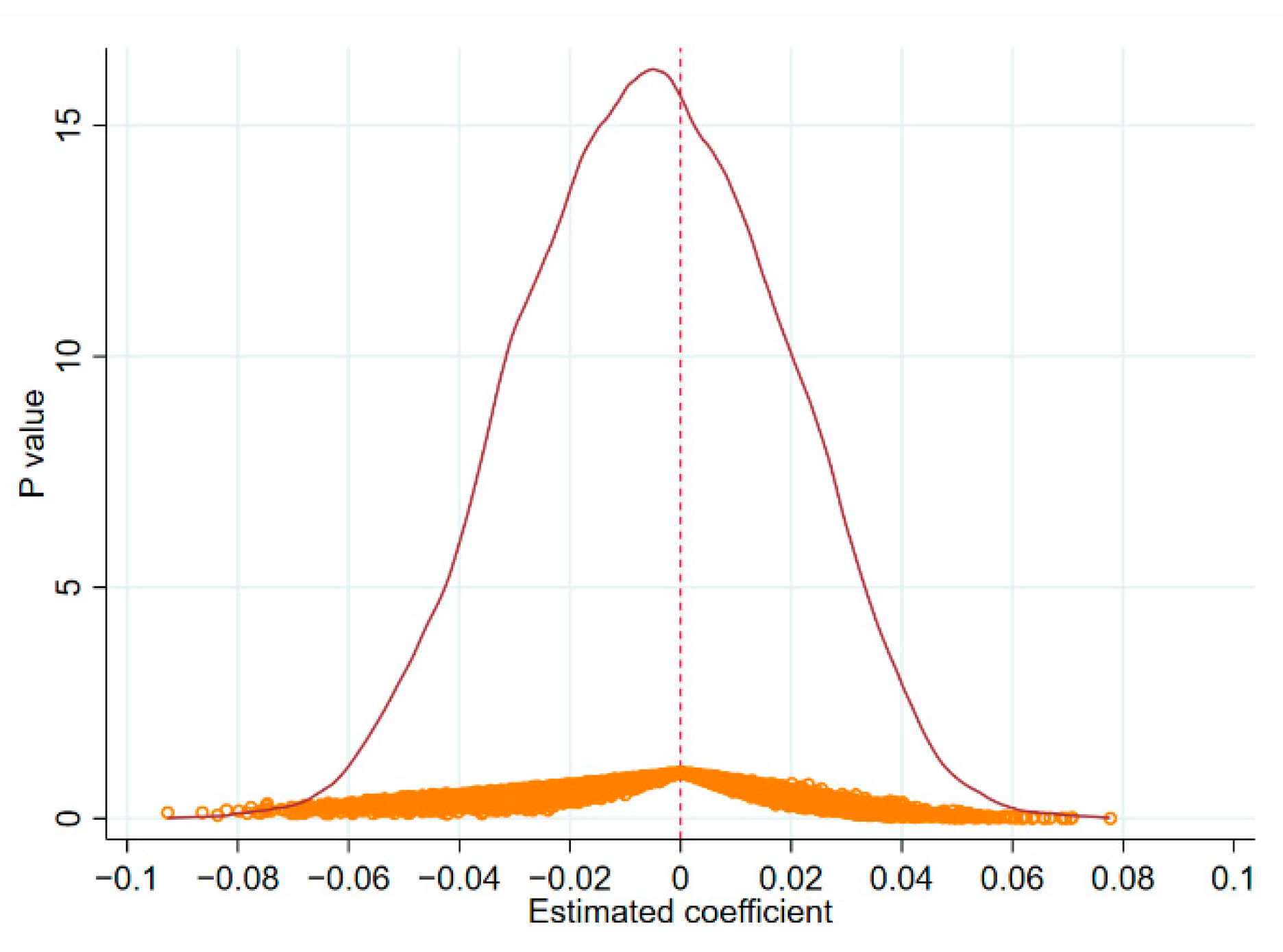

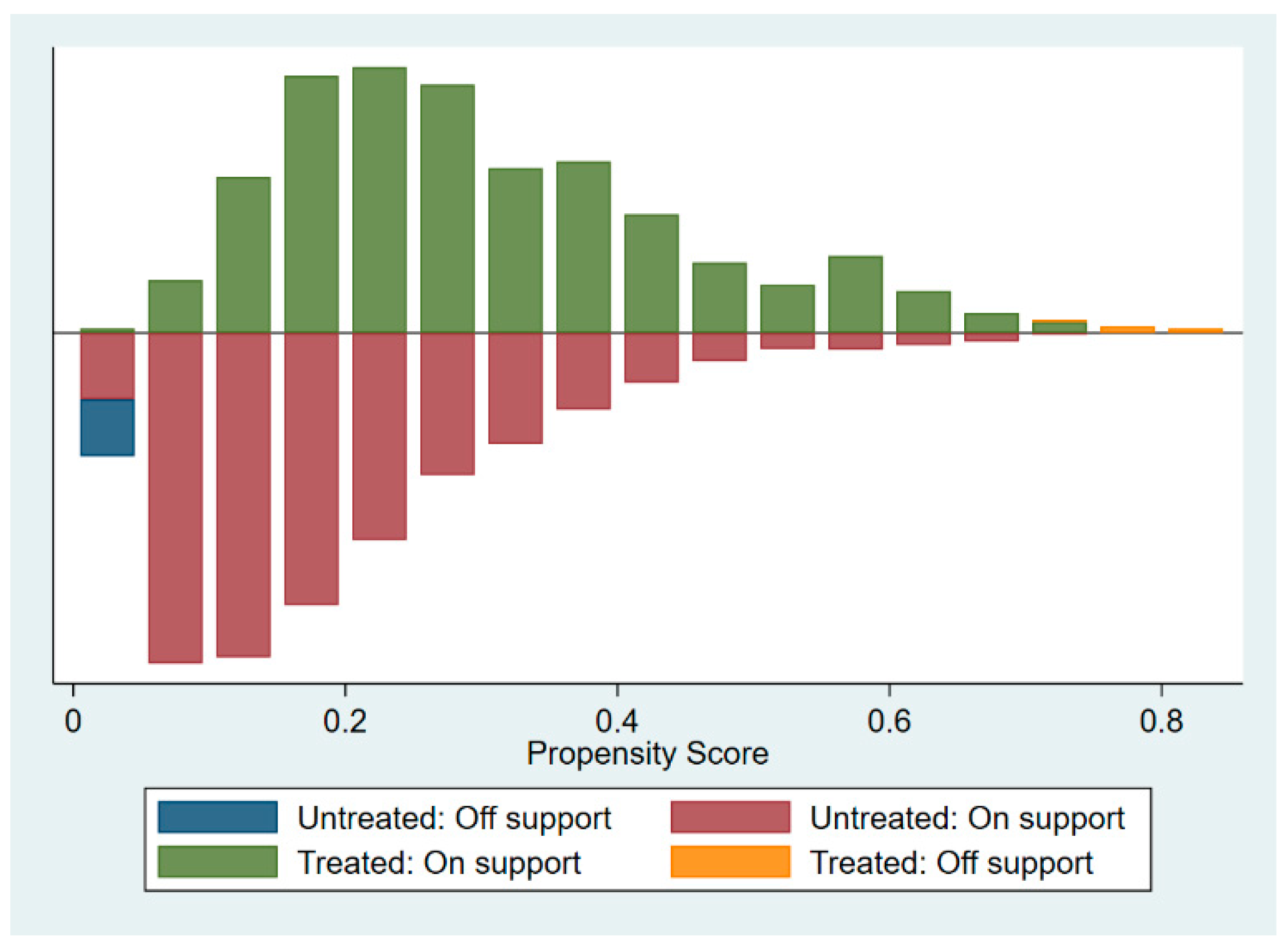

(1) The implementation of the CEPL improved the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities. The empirical results of the DID model show that when other conditions remain unchanged, after the implementation of the CEPL, the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities has been significantly increased. After selecting instrumental variable, changing the estimation model, using PSM+DID and other methods to re-estimate, the results are still robust. This finding confirms that environmental regulations and policies have a positive impact on the utilization of ISW and also expands the field of research on the factors influencing ISW.

(2) After analyzing the mechanism, it was found that the higher the city’s environmental regulation score, the more obvious the effect of the CEPL on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW. This is mainly because the higher the environmental regulation score of a city, the stronger the environmental law enforcement of the city, the more likely it is to ensure the smooth implementation of the CEPL in the local area. Combined with the results of the instrumental variable method in the robustness test, this finding confirms the applicability of the “political tournament” theory to environmental management issues, that is, the inclusion of environmental performance in the promotion assessment system of officials is effective in improving environmental quality.

(3) The promotion effect of CEPL on comprehensive utilization rate in resource-based cities is heterogeneous. From the perspective of resource-based cities, the CEPL has a significant effect on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in grow-up and recessionary resource-based cities, but it has no significant promotion effect on growing and regenerative resource-based cities; from the perspective of different region, the CEPL has a significant effect on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities in the central region, but this effect is not obvious in the eastern, western, and northeastern regions of China. This finding provides an important reference for developing the policies to manage ISW in different cities’ type.

6. Discussion

Based on the empirical finding that the implementation of CEPL improves the combined utilization of cities’ ISW, to improve the level of solid waste management in cities, environmental policies and regulations are indispensable tools. The market-led solid waste management sometimes fails due to the defects of the market itself and the government needs to formulate relevant policies and regulations as a supplement to improve the level of municipal solid waste management. Meanwhile, environmental law enforcement is the cornerstone of ensuring the effectiveness of policies and regulations. The stronger the environmental law enforcement, the more obvious the role of policies and regulations in improving the level of solid waste management. Therefore, the government should strengthen environmental law enforcement to ensure the implementation of relevant policies and regulations. In addition, to ease the pressure on resources, speeding up the industrial transformation of resource-based cities is the fundamental way. Local governments should take into account local conditions and formulate sustainable development plans that are in line with local conditions.

The contribution of this research to the literature on ISW management is to enrich the theoretical foundation of the research on the factors affecting the management of municipal solid waste. It has a strong reference value for the practice of municipal solid waste management. Moreover, this study provides new ideas for changing the urban solid waste management model and realizing the “win−win” between the economy and the ecological environment. That is, in addition to the market and technical means, strong policies, and regulations are also effective tools to improve the level of municipal solid waste management.

Nevertheless, limitations exist. First, Although the robustness test was carried out by changing the sample, selecting the instrumental variables, and changing the estimation method, etc., however, there may be some important variables that have not been considered and have not been controlled. Further, although this study analyzes the impact of CEPL on the comprehensive utilization rate of ISW in resource-based cities and its impact mechanism, the analysis is not comprehensive due to there may be other mechanisms that have not been considered. Future studies should extend the framework to a more comprehensive context.