1. Introduction

In Indonesia, 75% of generated waste is caused by food consumption [

1]. This is a consequence of increasing consumption on the consumer’s part, along with unsustainability in food packaging and food waste [

2]. Firms must consider the environmental, economic and social impact (triple bottom line; TBL perspectives) in their food product assessment, and consider efficient practices leading towards sustainable consumption. Indeed, sustainable consumption requires an understanding of consumer behavior, and sustainable consumption behavior (SCB) requires additional efforts to develop and is difficult to trigger spontaneously [

3]. The reciprocal rules in SCB indicate that a beneficial action on the part of consumer behavior leads to a response in kind, regarding the social impact of multilateral relationships [

4]. For instance, consumer behavior can be examined by a close inter-personal demographic to determine environmental responses drawing from SCB [

5,

6]. Moreover, Yang et al. [

7] argued that, since SCB is pro-environment, consumers display altruistic characteristics which are expressed in their value selection and self-identity construction, in order to fulfil their needs, while reducing the impact on the environment. Yet research addressing how consumer behavior impacts on environmental and social aspects in structuring the SCB model is still lacking [

8]. Even though various aspects and criteria have been proposed to measure the SCB, the hierarchical structure in the nature of the measurement model is still underdeveloped.

In this study, SCB explores sustainable consumption related to consumers’ backgrounds related circumstances, along with the improvement of strategies involved in exchange relationships based on social exchange theory (SET), due to the expected benefits in economic and social resources [

6]. In terms of theoretical insights, SCB aims to understand the waste of resources, with the aim of preserving environmental sustainability, in which consumers can help in reducing their social impact, consumer behavior is involved in the resource exchange processes, and the importance of demographic features forming the SCB model is considered [

5]. Food consumption has an impact on individual and public health, natural resources, social cohesion and the economy; nevertheless, the complexity of consumer behavior and their fundamental knowledge is difficult to explain from a single viewpoint [

9,

10,

11]. As aforementioned, SCB supports corporate sustainability while supporting the firm to arrive at economic benefits, and positive environmental impact and social effects; especially, environmentally-friendly product consumption is a trend, via which consumers change their behavior to achieve sustainability [

4,

10,

12].

For instance, Chen et al. [

13] suggested that communication efforts dedicated to educating consumers about the environment and knowledge of conservation affect SCB. Effective environmental responses require efforts to gain an understanding of the relevant concept regarding consumers’ behaviors and to further explore attributes encouraging consumer intention to understand the SCB model [

4]. Alzubaidi et al. [

14] argued that attributes affecting consumers’ environmental responses are affected by innovativeness, perceived consumer effectiveness, and environmental concerns. However, there are still attitudinal behavior inconsistencies in how consumers perceive products and in the understanding of consumers’ socio-economic and demographic profiles [

5,

8]. Indeed, SCB has not fully alleviated these situations and has not covered this broader range of activities, despite studies in the resolution of the problem of addressing and becoming acquainted with SCB [

13,

15].

Since increasing attention has been paid to consumers changing their consumption behavior toward sustainability, this study argues that the SET needs to understand social impacts and consumers’ responses to the environment, in order to construct a holistic SCB model [

4,

9]. Basha and Lal [

16] argued that social pressure changing consumer behavior is urgent and offer valuable insight into how SCB conceivably might transform the situation to a more sustainable supply, production and consumption. In addition, Sarkis et al. [

11] claimed that social impact effectiveness is necessary to warrant the development and adoption of the successful economic development new categories and consumption models to involve new behaviors and measure this accomplishment precisely. Schäfer et al. [

15] pointed out that in sustainable consumption it is essential to understand the contextual and causal influences. Ganglmair-Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft [

17] argued that, apart from individual characteristics, there is a wide variety of other influencing factors in the dynamics of consumer behavior regarding sustainability. The SCB model deals with consumer’s behavior in changing resistant daily routines and therefore creating more positive social impacts; however, the model has to be structured taking into account contextual and causal influences.

This study applies the Delphi method and a fuzzy decision-making trial evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) together to develop valid measures and a causal model. First, a measurement SCB model is proposed, described in qualitative information. The Delphi method is intended to structure and validate the selected attributes from the literature and expects’ opinions [

18,

19,

20]. Secondly, Fuzzy DEMATEL transforms the customer perceptions into quantitative information and visualizes the interrelationships among attributes [

21]. However, the experts’ experience, knowledge, and familiarity with the field may cause biases judgments that effect the results [

22]. Further, there are lack of tools to enable interactions among the attribute since they are presumed as exhaustive and independent. Next, Choquet integral is used as a non-additive fuzzy integral to eliminate the expert subjective problems and interactivity method; thus, it provides higher insight on validating hierarchical structure [

23,

24]. The objectives of this study are as follows:

To present a set of SCB attributes;

To examine the causal SCB model in qualitative information;

To identify the improvement criteria for practice.

The contribution of this study lies in both theoretical and managerial views: (1) a set of valid SCB aspects and criteria are presented to extend the SCB knowledge in the literature; (2) The SCB causal interrelationship model is justified; and (3) criteria are indicated for the improvement of practices to enhance performance. The remainder of this study is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the literature review related to SET, SCB, proposed method and attributes for measurement.

Section 3 describes the industrial background and methodology.

Section 4 provides the results and major findings from the data analysis process. Theoretical and managerial implications are provided in

Section 5. The final section covers the conclusion, contributions, limitations and opportunities for future research.

3. Methods

The background of food industry in Indonesia is presented, and the Delphi method and fuzzy DEMATEL are explained.

3.1. Industrial Background

Indonesia’s food industry has been growing rapidly because of its significant contribution to the national economy. Indonesia has a population of approximately 267 million people, making it one of the largest markets for the food industry in South East Asia. The country is developing rapidly, and an increase in the number of office workers has subsequently led to a growth in both disposable income and household consumption [

1]. These conditions have also been followed by increasing consumption and unsustainability of food products. The food industry fulfils consumer needs and rarely considers environmental effects such as pollution, scarcity of natural resources, and environmental degradation. Consumers’ decisions are based on an eagerness to consume certain products rather than on their environmental knowledge about saving future generations. In the process, there is a lack of sustainable knowledge during consumption, and the food industry is responsible for educating consumers about sustainable consumption behavior. Consuming foods in a sustainable way is becoming one of the most popular ways of solving environmental problems. Consumers who are engaged in such behavior show respect for the environment.

However, the growth of the Indonesia food industry is having an impact on the environment. Rising incomes among the growing middle class and millennialism, changes in lifestyles due to their large number and unique consumption behavior. Indonesia presents the sustainable consumption of food as having great potential for development in response to challenges with unsustainability (e.g., environmental pollution, scarcity of natural resources, and environmental degradation). For related reasons, social, economic, environmental, consumer demographic and consumer behavior have been subjected to considerable sustainability consumption behavior.

3.2. Delphi Method

The Delphi method is to categorize the knowledge and abilities of a group of experts in a unique objective develop a comprehensive set of attributes [

19]. Hsu and Sandford [

33] applied this method to determine, expose and explore settlements in different judgements, grouping unorganized attributes by initiating the respondents. Von Bergner and Lohmann [

32] stated that the method is suitable for exploratory qualitative study to inquire about experts’ sentiments regarding novel of ideas or complex problems by conducting several questionnaires and controlled feedback. This study uses face-to-face interviews for information gathering in the Delphi method. The attributes are derived from the literature and validated by industrial experts. The attributes were collected by reviewing the related literature to secure agreement among respondents, with the experts being requested to confirm the importance of the attribute using a nominal YES/NO scale. Agreement on the inclusion of indicators was based on a 75% or higher consensus score [

20].

3.3. Fuzzy DEMATEL

The DEMATEL is an effective tool to resolve complex interrelationship problems where the interrelationships among cause and effect attributes are transformed [

21,

42]. Fuzzy DEMATEL uses defuzzification to transform qualitative information into fuzzy linguistic information. The process is to obtain crisp values from triangular fuzzy numbers (TFN). The left and right values are determined by the minimum and maximum numbers and are transformed into crisp values [

43]. Fuzzy membership functions

are used to compute the total weighted values. The crisp values are displayed in a matrix of total direct relation for mapping a diagram to simplify analytical results. The cause and effect groups that contain certain attributes represent the structured interrelationship and effects. Therefore, a set of attributes is proposed,

, certain pairwise interrelationships is used to create the mathematical relation.

This study uses a linguistic scale of VL (very low influence), L (low influence), M (moderate influence), HI (high influence), and VHI (very high influence); see

Table 2. Assuming that there are

members in the decision group, the assessment of

, denotes the fuzzy weight of attribute

which affects the attribute

and is assessed by evaluators

.

The fuzzy numbers are normalized as:

where

.

The left

and right

normalized values are computed using:

The total normalized crisp values

is generated as:

The synthetic values notation to accumulate the individual perceptiveness from

respondents is adopted.

The initial matrix of direct relation is a matrix that is acquired by pairwise comparison. In this matrix, is assigned as the level to which attribute affects attribute , amended as .

The normalized direct relation matrix

is created using,

From the normalized direct relation matrix, the interrelationship matrix

is obtained by:

where

refers as

.

The values of the driving power

and dependence power

are obtained from the sum of rows’ and columns’ values of the interrelationship matrix by applying the following equations.

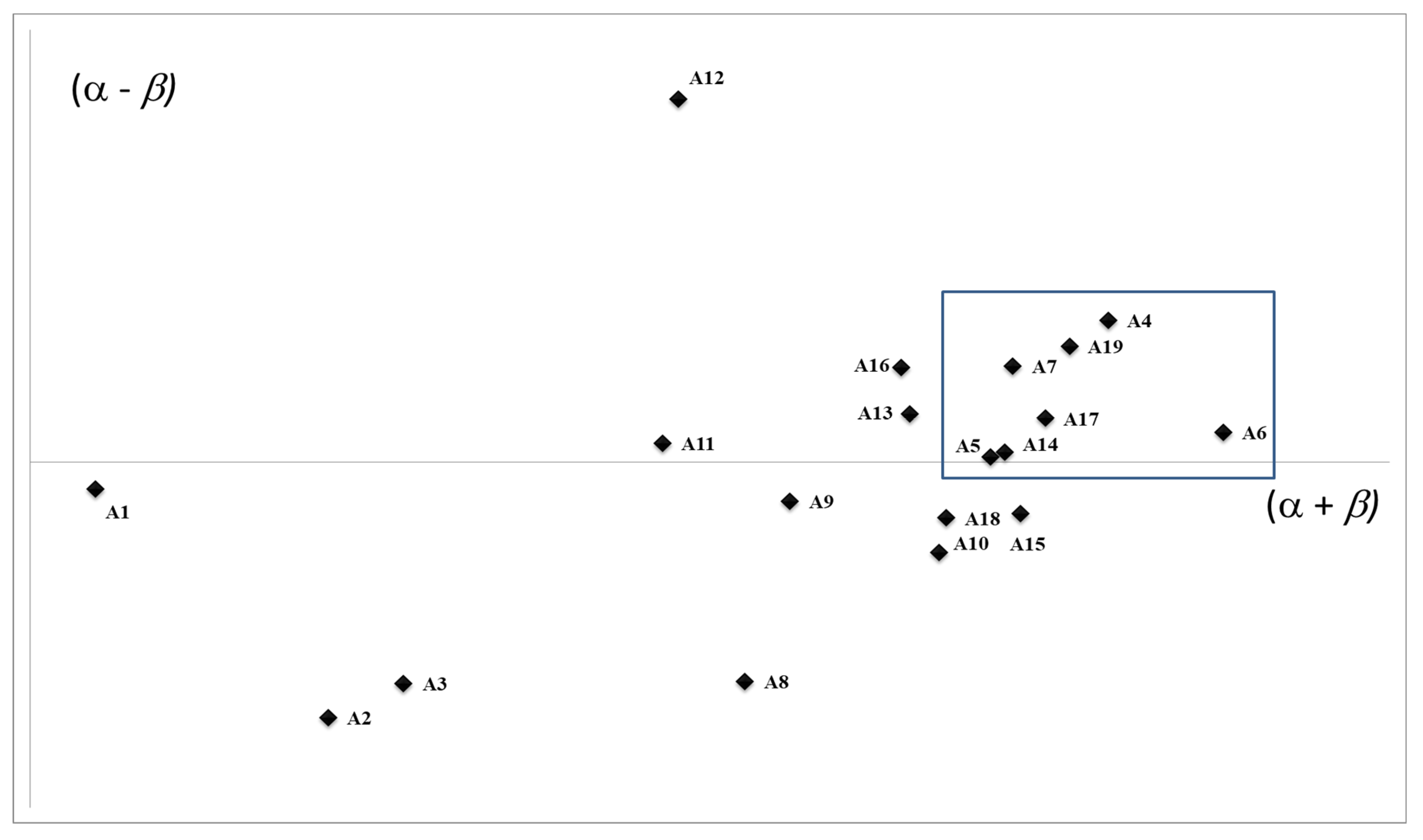

The attributes are positioned in a cause—effect diagram by adopting , which are in turn horizontal and vertical axes. (α + β) exhibits the importance of attributes, indicating that the higher the values of (α + β) are, the more important function of the attributes is. classifies the attributes into cause and effect groups by considering values as positive or negative. If is positive, the attribute belongs to the cause group; if the value is negative, it is in the effect group.

3.4. Choquet Integral

There are need to pre-allocation the expert weights and solve incomplete preference interrelations when the expert evaluation is unknown and their judgement favoritisms are linguistic and uncertainty [

23]. The unweighted supermatrix is obtained to deal with the relationship of feedback the criteria [

22,

23]. Once the matrix is unable to imitate to the column stochastic determinant, the expert is required to provide the weights to adjust it as a weighted supermatrix. As a result, the gradual convergence of the interrelationship is obtained to accurate the relative weights among the criteria using:

The choquet

integral, as the non-additive fuzzy integral, is a numeric-based approach, which has been used for both pattern recognition and image segmentation. Adoption of a fuzzy integral in membership aggregation, rather than a traditional aggregation operator, leads to an important distinction as to how processes of fuzzy integration are utilized. The success of a Choquet integral depends on an appropriate representation of fuzzy measures, which captures the importance of individual criterion or their combination [

44,

45]. Sugeno [

46] introduced monotonic and non-additive fuzzy integrals to express the grades of importance for attributes, which is useful to model the preference structure. Fuzzy measure can be explicated as the subjective importance of a criterion during the evaluation process [

23]. Sugeno and Terano [

47] incorporated the

λ-additive axiom to reduce the difficulty of collecting information. In fuzzy measure space (

X, β, g), let

. If

, then the fuzzy measure g is

λ-additive. This particular fuzzy measure is termed as

λ-fuzzy measure because it has to satisfy

λ-additively, named Sugeno measure.

Assume that X = {x1, x2, x3, …, xn} and P(X) is the power set of X, the set function g: P(X) → [0, 1] is called a fuzzy measure, which is non-additive and preserves the following properties:

;

g(X) = 1;

if and then (monotonicity);

In P(X), if , and , then (continuity from below);

In P(X), if , and , then (continuity from above).

In addition,

λ-fuzzy measure has the following additional properties:

where

λ > 0 for all

and

. If

X is a finite set, then

. The

λ-fuzzy measure

g satisfies the following:

where

for all

i,

j = 1, 2, 3, …, n and

. In Equation (14),

indicates that the

λ-fuzzy measure

g is non-additive; otherwise, the

λ-fuzzy measure

g is additive and there is no interaction between

Ai and

Aj for

. The interaction means there is information fusion between criteria [

45].

λ > 0 implies that

and the set {

A, B} has multiplicative effect, whereas

λ < 0 indicates the substitutive effect of the set {

A, B} [

48]. In fuzzy measure space (

X, β, g), let

h be a measurable function from

X to [0, 1], the definition of the fuzzy integral of

h over

A with respect to

g is

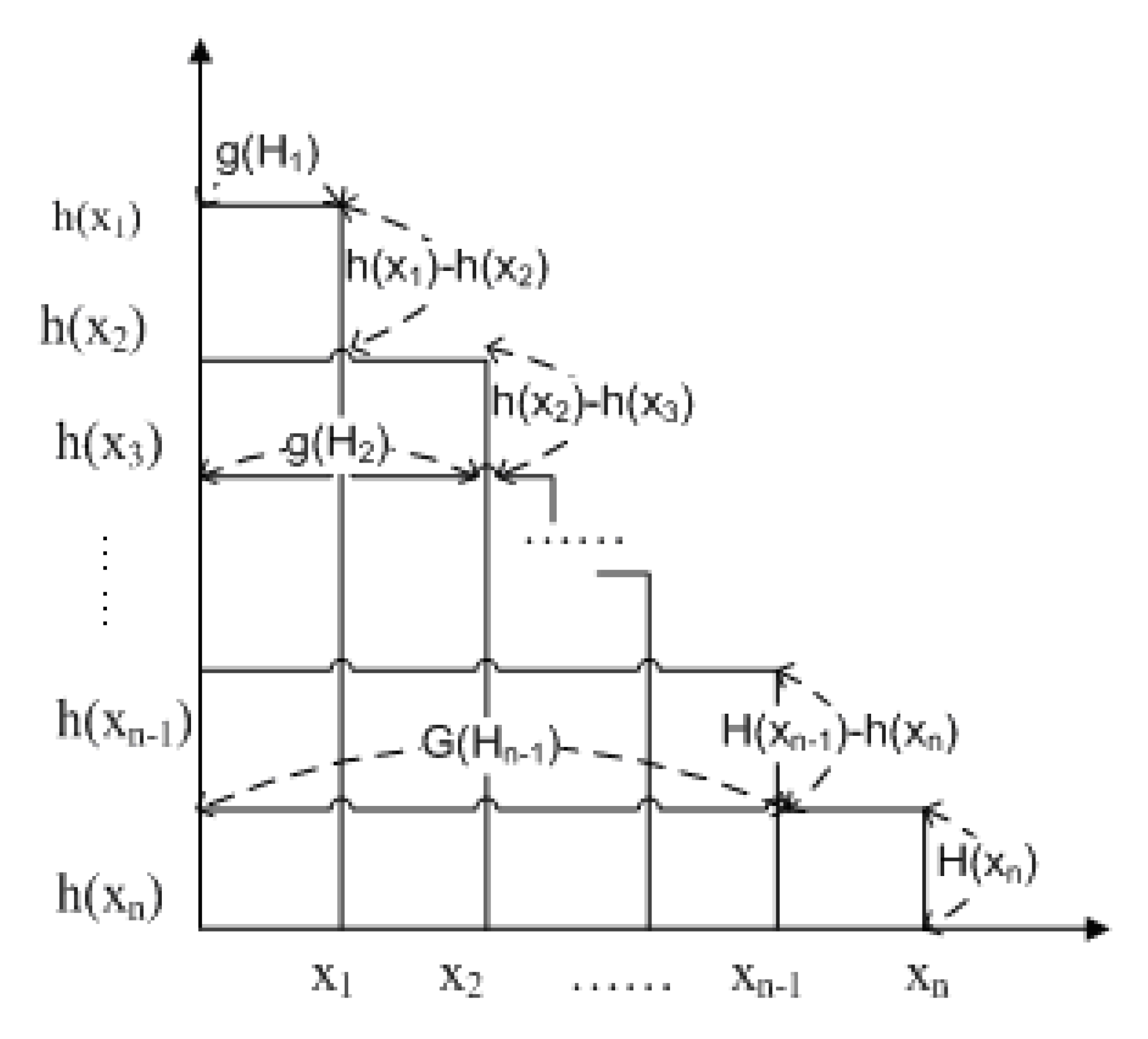

where

Fα = {

x|

h(x) ≥

α}.

A is a domain of fuzzy integral. When

A = X, the fuzzy integral can be denoted by

∫hdg. Consider a fuzzy measure

g of (

X, P(X)) and

X is a finite set here. Let

h: X → [0, 1] and assume without loss of generality that the function

h(xi) is monotonically decreasing with respect to

i, for instance

h(x1)≥ h(x2)≥…≥ h(xn). To assure that the elements in

X be renumbered, we acquire the following equation:

where

H = (

x1,

x2,…….., xi),

i = 1, 2,…,n. In practice,

h can be regarded as the performance on a particular attribute for the criteria;

g presents the grade of subjective importance of each attribute. The fuzzy integral of

h(x) with respect to

g gives the overall assessment of the attribute. To simply the calculation, the same fuzzy measure of choquet integral is expressed as follow:

where

,

and

Hi = {

x(i),……, x(n)}. In literature, the fuzzy integral defined by

∫hdg is called “choquet integral.” The basic concept can be illustrated in

Figure 1. The fuzzy integral measurement model needs not assume independency among alternatives; it can, therefore, be used in nonlinear situations.

3.5. Data Collection and Proposed Analysis Steps

This study uses the opinions of thirty experts with more than 10 years extensive experience in the field to assess the food industry. A team of 30 experts consisting of 16 experts from academia and 14 professionals from the practical area is approached. An online discussion was organized to acquire the experts’ judgements and confirm their agreement with the significant attributes that need to define SCB structure based on the Delphi method. Then the questionnaire is delivered to collect their linguistic evaluations on the SCB attributes and assure the analysis authenticity of Fuzzy DEMATEL and Choquet integral. The experts’ information is presented in

Appendix A.

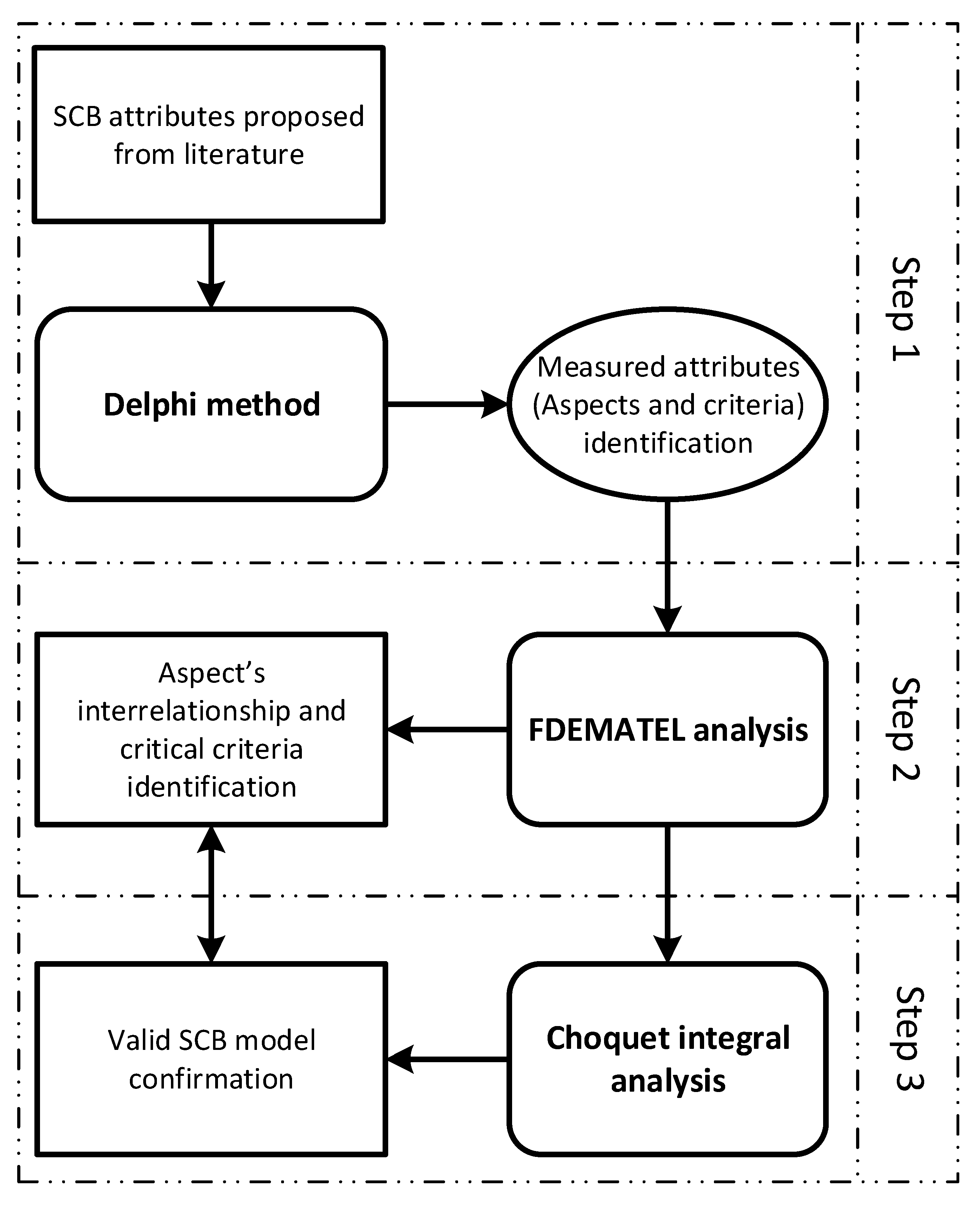

The analysis steps were proposed, as shown in

Figure 2.

The SCB attributes is identified in the literature the confirmed with the expect by using the Delphi method.

The experts’ linguistic evaluation on SCB attributes is collected by employing the questionnaire, which is formed based on the confirmable attributes. Fuzzy DEMATEL is used to develop valid measures and a causal model of SCB.

Choquet integral is utilized to eliminate the expert subjective problems and provides higher insight on validating hierarchical structure.

5. Implications

This section addresses the theoretical and managerial implications identified by this study. Contributions to both the theoretical literature and practice are presented.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature by exploring the causal SCB aspects, and the results provide insights that could prove useful in addressing SET. Social impact and consumer behaviour should be regarded as important during the SCB process.

This study provides empirical evidence suggesting that consumer behavior is a causal attribute. Consumer behavior impacts the effect group in various ways because consumers’ behavior may have high place attachment for improving quality of life. On the theoretical level, consumer behavior as an individual’s motivation in his/her plan or decision to exert effort in performing a specific sustainability behavior. This create a pros/cons as contradicting consumer’s action toward sustainability is driven by economic benefit and social impacts [

7,

17]. In this study, consumers’ attitudes affect different dimensions of sustainable consumer behavior through the economic benefits and social impacts, especially with regard to the environment [

8,

9,

11]. Consumer behavior has a strong relationship with social impact for achieving sustainability consumption behavior [

25,

36]. These results also show that consumers learn such behavior from their mothers, which means that consumers in our environment and society also play an important role because their actions are imitated [

3,

37]. Consumer demographic is interrelated to the consumer behavior and consumer behavior producing a significant relationship to environmental responses. This SCB model is providing an insight view for a hierarchical model in qualitative information.

The result shows that social impact, belonging to the causal group, has a critical effect on other aspects. The social context is important for impacting SCB, especially in facilitating sustainability practices in which consumer are embedded with social norms. Thus, this study suggests that these aspects can be used to secure a sustainable competitive advantage by motivating and benefiting consumers who engage in sustainable food consumption and by bringing other resources together. Social approaches generate consumer behavior and thus help in developing more sustainable forms of consumption behavior that directly improve SCB [

13,

15]. Consumer behaviour is also emphasized because consumer behavior could easily be facilitated by social or peer influence to conform to pressure from others [

16,

41]. Consumers may observe others’ behavior and imitate their actions to as responding to the environmental action [

4,

13]. Consumers have another reason to show that they desire to build or enhance their self-identity regardless of affluence levels and influence the behaviour of consumers.

Nevertheless, economic benefits are also an important aspect in SCB causal interrelationships. Consumers obtain economic benefits through transaction incentives. Consumers compare benefits and costs to motivate them to be less wasteful. Increasing consumption will contribute to economic growth. However, consumption is either directly or indirectly the source of most environmental issues, and it also plays a major role in creating many social and financial problems [

3]. Since there is a high level of financial and phycological and social risk, these problems can be avoided based on the good perceptions of consumers. Therefore, building and developing consumer-friendly trends from consumers and creating demand for green products in the market are needed. The government also participates in economic benefits by providing policy and regulation standards for incentives. Cooperation between the government, manufacturers and consumers is required to implement SCB.

5.2. Managerial Implications

SCB criteria are identified to provide managerial insights for decision makers. Within this context, these criteria are helping to improve the sustainability of Indonesia’s food industry and are already being explored.

Perceived consumer effectiveness (C6) helps to connect and improve SCB. Consumers believe in the effort they make regarding different solutions to existing problems. From a positive point of view, individual beliefs about chosen actions can produce a positive or negative change in the situation. This criterion affects specific consumer behavior by indulging and supplying a positive attitude regarding SCB and the environment, which helps to explain behavior. Consumers who have higher perceived consumer effectiveness are generally more environmentally conscious and have greater concern for ethics. Environmental and social information about food products is personally relevant to such individuals. Therefore, different thinking to enhance the perception of effectiveness is useful. Some consumers have made extensive efforts to reduce environmental harm, while others believe that their effort cannot make any difference. Making consumers believe that their actions might help solve an existing problem and will possibly have an effect on reducing resource challenges.

Consumer trust (C4) is interest in the organic food consumption. In an industry context, trust bring positive or negative effects for SCB development and continuation during individual decisions. A lack of trust from consumers generates inconsistency in food consumption. Trust is also not easy to manage because consumers are varied and lack knowledge about the components inside products. When consumers consume food products, they should believe that the product effectively fulfils a function and all of the process was from an organic supply chain. Firms should convince consumers about the benefit or advantages that they obtain when consuming food, such as environmental or health benefits, and firms should fully convince them that products are produced in an environmentally friendly way. Trust can also be obtained from effective communication campaigns or activities in practical terms or with regard to their elite image (expensive, special), authenticity, healthiness, social influence, naturalness, and quality. Effective verbal communication about certification and product composition can impact consumers’ trust and shape consumption behavior in favour of sustainable consumption.

Environmental responsibility (C19) explains the sense of responsibility to protect the environment, which is always based on the perception of consequence. Increasing responsibility among consumer can help promote SCB. Consumers show their environmental responsibility through their lifestyle and sacrifices, which can help make the world more sustainable by encouraging others to participate in saving the environment. Consumers can also obtain information on environmental problems caused by human consumption and use it to change their consumption for the better. Since responsibility is usually based on self-interest, needs, legal obligations, consumer desires, motivation, positive influence on the environment and value, firms can campaign to increase environmental awareness and use the threat of the endangered environment to enhance environment responsibility.

Environmental knowledge (C17) assumed to motivate SCB. Consumers have environmental knowledge that influences on his/her and others’ environmental responses, attitudes and participation towards sustainable consumption and may be used as a solution for the environmental problems. Therefore, more information provided would lead to increased consumer knowledge, which in turn might strengthen consumers’ trust in products and reinforce the attitude-behavior relationship. Conversely, a lack of knowledge prevents consumers from translating their concerns into the actual purchase of products. A deeper understanding of the consequences of irresponsible consumption might prove to be more effective in causing consumers to shift towards sustainable consumption. Consequences can be appropriate to motivate their decision-making, as it relates to product purchases. Consumer knowledge about the cause and impact of pollution also leads to a level of awareness regarding their consumption consequences.

Behavioral intention (C7) shows the essential criteria to improve the performance of SCB. Consumers who have behavioral intention can perform a specific behavior for the conservation of the physical and social environment for future generations. Attitudes towards consumption behavior are considered for evaluating a particular behavior intention that leads to a specific behavior with certain consequences. Therefore, individuals tend to possess a favourable attitude when the outcomes are positively evaluated, and thus, consumers are likely to engage in that specific behavior. To encourage behavioral intention, firms should facilitate or constrain actions to make it easier for consumers to perform their behavior under social pressure.

Social consumption motivation (C14) causes someone to be willing to put extra effort into performing a specific behavior, such as carrying out various activities that become a responsibility and fulfilling an obligation in order to achieve social status. Social consumption motivation is about perceived and actual judgements from their significant peers; consumers acquire possessions to display their self-achievement and happiness in order to maximize their social status. Motivation can also show whether consumers are satisfied with the product they consumed and its influence on the environment, which can motivate them to engage in SCB. This study suggests that successful social consumption motivation encourages consumers to consider the environmental, economic and social aspects during the consumption process and provides inspiration to improve the situation for current and future generations. Therefore, firms should take note of the social environment that is creating the social motivation for their consumers to engage in sustainable consumption.

Consumer emotion (C5) reflects specific actions or behavior by generating feelings of social connection. Building positive emotions in consumers is important for firms throughout the industry as a new revolution to promote sustainable consumption. Nevertheless, a lack of building emotions results in the loss of consumers and elimination of participation in SCB. This study recommends that in building consumer emotions can increase their motivation to reduce SCB failure. Consumer emotion fulfils psychological needs, and positive emotions from their consumption attitude drive behavioural intention.

6. Conclusions

This study builds a hierarchical SCM model in qualitative information using Delphi method and fuzzy DEMATEL method to approach and explore the attributes that influence sustainable consumption in the Indonesian food industry and Choquet integral is used to eliminate the expert subjective problems and interactivity method, thus, provides the hierarchical insight for effectively addressing the aspects and criteria. From the SET interrelationship context, this study provides a valid set of five aspects and 19 criteria, including consumer demographics, consumer behavior, social impacts, economic benefits, and environmental responses. This study partially fulfills the gaps from consumer demographics and consumer behavior approach. The qualitiave information is hard to be transformed into comparable data. This study handles the qualitiave information and addresses the hierarchical and interrelationships in SCB model.

The results show that social impact and personal behaviour are the strongest causal aspects that improve SCB. As a part of exchange theory, these criteria influence SCB improvement through practice. The aspects explaining the social impacts are easily facilitated by personal behaviour, which influences consumers with regard to how they should behave to minimize waste and be efficient with resource use. Thus, social impact gives consumers the opportunity to imitate others’ behaviour and encourages them engage in SCB. Sustainable consumption behaviour leads to economic benefits, and consumers play an important role during implementation; their attitude towards SCB also originates from the benefits that are perceived to confirm their intention to practice sustainability. Perceived consumer effectiveness, trust from consumers, environmental responsibility, environmental knowledge, behavioural intention, social consumption motivation, and built emotion are found to be the leading criteria in approaching SCB. Consumers develop different solutions to their problems during their consumption, and their perception of effectiveness in reducing environmental harm leads to sustainable behaviour.

The contributions of this study are as follows. This study developed theoretical hierarchical SCB structure and a causal relationship model among the attributes; particularly, the consumer behaviour has influence on social impacts and environmental responses are with main causal relationships. Social impact gives consumers the opportunity to imitate others’ behavior and encourages them engage. SCB model leads to both economic and environmental benefits, and consumers play an important role during implementation to sustainability. In practices, the top important criteria are found to address the sustainable consumption behaviour improvement.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the proposed aspects and criteria are measured suing qualitative information with limited applicability in uncertainties. Future study might involve more quantitative data. The consumer demographical information might be exploring in the future studies. Second, the evaluation only within 30 experts. the future study might also enlarge the sample size to calibrate and justify the model, as well as could apply the sensitivity analysis to understand the customer perceptions under difference scenarios. Third, this study constructed its hierarchical framework based on the SCB theoretical background in food industry. Additional studies may extend the case to other industries or other countries to examine the practical differences between cases.