Abstract

There is widespread recognition that a transformation of food systems is needed to improve environmental sustainability. As part of efforts to hold food companies accountable for their role in improving the environmental sustainability of food systems, there is a critical role for monitoring and benchmarking of company actions. This study aimed to develop a proposed set of metrics for assessing the commitments and practices of food companies regarding environmental sustainability. Guided by an inventory of existing sustainability reporting frameworks and benchmarking initiatives, we proposed 37 indicators for assessment, categorised into ten domains, covering strategy, packaging, greenhouse gas emissions, energy use, water, biodiversity, food waste, compliance and reducing animal-sourced foods. We refined the indicators after consultation with academic experts. We discussed implementation feasibility with sustainability managers from three major food companies in New Zealand. Feedback highlighted the need to pilot test methods for applying the indicators in practice, including assessment of a company’s impact across the supply chain, refining indicator scoring criteria, and weighting indicators based on company- and sector-specific priority areas of focus. Assessment of food companies using the proposed set of metrics can improve accountability for action and inform government regulatory responses.

1. Introduction

A successful food system should ensure the equitable distribution of high quality, nutritious foods while limiting harmful impact on the environment [1]. However, current food systems contribute to substantial environmental damage [2,3,4]. Globally, food production and food retail are responsible for one-third of the total greenhouse gas emissions [2]. Emissions from the food sector are predominantly due to agriculture (71% of food system emissions) [5,6,7]; food loss and waste [7]; and storage, packaging and transport of food products [7]. The use of land for food production can also drive unsustainable land-clearing [5,6], which can have negative flow-on effects on local biodiversity [7]. Industrial food production currently accounts for 70% of global freshwater use [8], and unsustainable farming and land use for food production can degrade scarce freshwater resources [7], particularly through fertilizer use which has increased about 800% since the 1960s [5]. Without dedicated measures, the environmental impacts of food systems risk exceeding key environmental limits for climate change, land use, freshwater extraction and biogeochemical flows associated with fertiliser application [9].

As well as contributing to environmental damage, current food systems contribute to unhealthy population diets and high levels of obesity (over 2 billion people) globally [3,4,5], alongside 9.8% of the world population being undernourished [10], and thus are not on track to meet the Sustainable Development Goal targets by 2030 [5]. This poses a major risk to population health, with unhealthy diets and obesity responsible for more premature deaths and disability than any other risks globally, including tobacco smoking [11]. Research by the EAT Foundation and The Lancet show that optimal diets for human health are also often the most sustainable for the planet [3]. For the global population to shift to more healthy and sustainable diets, consumption of plant foods (such as fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes) needs to increase, while consumption of animal foods, such as red meat and dairy, needs to decrease overall (although not necessarily for all geographic areas and/or population groups) [3]. Moreover, food production is likely to face mounting challenges from increasing climate variability and weather extremes, posing major barriers to efforts to improve food security and address malnutrition in all its forms [4]. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for a reorientation of global food systems such that they are both healthy and environmentally sustainable. Correspondingly, there are enormous potential benefits from ‘double-duty’ actions that can make food systems healthier and reduce negative environmental impacts [4].

Private sector organisations play a central role as part of food systems. Over recent decades, as food production has become increasingly globalised, a small number of large transnational corporations have become responsible for producing and selling a vast proportion of the global food supply [12]. These corporations, including food and beverage manufacturers, quick-service restaurants and food retailers, now play dominant roles in most food systems globally through their influence on the way in which foods are developed, supplied and marketed [4]. In addition, the increasing market concentration and power of the food industry has meant that a relatively small number of food companies are in a position to exert their influence over governments and policy processes. There is a mounting body of evidence that large food companies use a broad range of strategies to exert their influence in order to protect profits by either delaying or circumventing implementation of globally recommended actions to improve the healthiness and sustainability of diets [4,13].

Importantly, the actions of the food industry can play a key role in addressing many of the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG2: Zero Hunger; SDG3: Good Health and Wellbeing; SDG6: Clean Water and Sanitation; SDG7: Affordable and Clean Energy; SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production; and SDG15: Life on Land [14]. While some food manufacturers and retailers have taken steps to address aspects of these goals, particularly those related to food production (such as sustainable packaging, reducing energy use and food waste), food industry policies and actions related to environmental sustainability have generally been weak and fall far short of climate and health expert recommendations [4]. Further, the consequences of unsustainable food systems, such as climate change, environmental degradation and diet-related chronic disease, continue to worsen, indicating that more radical change within the food system is urgently required. The Lancet Commission on Obesity, and others, have argued that stronger accountability systems are needed to ensure that private-sector actors respond adequately to the global problems of obesity, undernutrition and climate change [4,15].

Use of an accountability framework can guide food industry engagement and accountability efforts [16]. As part of an accountability framework, ‘taking the account’ includes an assessment of company reporting and disclosure of policies and practices. This allows various stakeholders to track progress and can enable benchmarking and enforcement against pre-specified objectives and metrics [16]. Benchmarking the policies and practices of the food industry can also lead to improved efforts to ‘respond to the account’, including by providing evidence to support regulatory changes that promote population health and environmental sustainability [17]. There are a number of reporting standards and guidelines that aim to encourage disclosure and enhance accountability of corporations with respect to environmental sustainability actions [18,19,20]. However, these reporting standards and guidelines, including prominent ones such as those developed by the Global Reporting Initiative [18], are almost all voluntary in nature and rely on individual companies to choose the metrics on which to report and the extent and nature of their disclosure.

Critically, many relevant standards and guidelines in the area have different areas of focus and specify vastly different metrics/indicators for reporting [21,22,23]. For example, the United Nations Global Compact initiative includes principles for voluntary sustainability commitments alongside human rights, labour and anti-corruption indicators [21]; the S&P Global initiative is a self-reporting tool for companies with 82 environmental indicators [22]; and the Food Loss and Waste Framework consists of guidelines for reporting standards in one specific area (food loss and waste) [23]. As a result, food company reporting related to environmental sustainability is currently highly variable, inconsistent and almost universally lacks comprehensiveness and specificity. In the area of environmental sustainability, specificity is particularly important, as illustrated by a recent analysis that highlights the importance of food companies delineating and distinctly reporting their Scope 1 and 2 emissions (direct and indirect emissions from sources that food corporations own and control) from their Scope 3 emissions (indirect emissions along the value chain that arise from food industry operations [24,25]. Identifying commonalities across standards, guidelines and indicators is required to elucidate which metrics are most integral to preserving environmental sustainability, as well as to provide a standardised means of assessing company progress across food supply chains.

One way that civil society, including researchers, can contribute to efforts to hold companies accountable for their actions related to environmental sustainability is through monitoring and benchmarking. The International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) is a global research network (currently active in over 60 countries) that aims to monitor, benchmark and support public and private sector actions to reduce obesity and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [26]. INFORMAS has developed a tool to benchmark food companies (manufacturers, quick-service restaurants and retailers) on their policies and practices related to nutrition at the national level [17]. This tool, the Business Impact Assessment on Obesity and Population Nutrition (BIA-Obesity), has been successfully implemented in various countries, including Australia [27], New Zealand [28], Canada [29], Malaysia [30], Belgium and France [31]. In recognition of the importance of considering both the health and environmental sustainability of food systems, INFORMAS is exploring the addition of sustainability indicators and metrics as part of its monitoring approach.

This study aimed to develop a proposed set of indicators for assessing the commitments and practices of food manufacturers, retailers and quick-service restaurants regarding environmental sustainability, and understand key considerations in applying the proposed set of indicators. The goal was to identify and build on existing reporting frameworks and benchmarking initiatives to inform future monitoring and accountability efforts, e.g., as part of INFORMAS, and inform the development of comprehensive reporting standards and guidelines in this area. In line with the principles of INFORMAS, we focused on indicators that could be applied at the national level, designed for external benchmarking of companies to be conducted with relatively limited resources. The study began with a literature review of existing reporting frameworks and benchmarking initiatives to draft a set of domains and indicators. This was followed by an iterative consultation process with academic experts and food industry sustainability experts to refine the indicators.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview and Scope

For the purposes of this study, environmental sustainability was conceptualised as the responsibility to conserve natural resources and protect global ecosystems to support human and planetary health and wellbeing [4]. In line with the way in which environmental sustainability has been discussed in relation to food systems [3,4,32], we focused on the following: packaging, greenhouse gas emissions, energy and water usage, biodiversity, food loss and animal-sourced foods. Nutrition-related aspects were excluded as these are already addressed by existing monitoring frameworks developed by INFORMAS and others [17,33]. Other social justice issues, such as gender equality and labour rights, as well as animal welfare, were not included.

In line with the aim of the study, the focus was on packaged food and non-alcoholic beverage manufacturers, quick-service restaurants and food retailers. Within these sectors, our focus was on those indicators relevant to the largest food companies within a country, as their policies and actions are likely to have the most impact on food systems, they are more likely to have publicly available commitments and many are likely to be publicly listed companies that are required to report annually on their activities related to sustainability as part of corporate sustainability reporting.

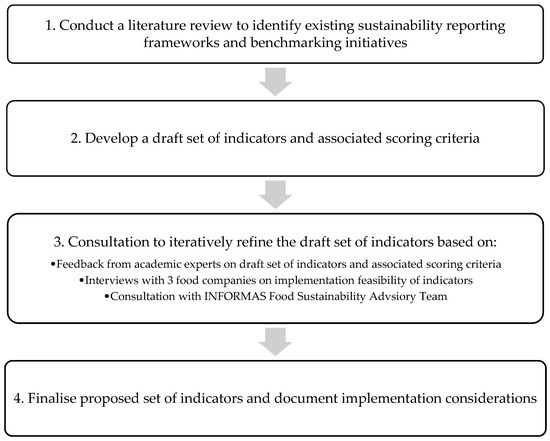

The process of developing the proposed set of indicators (see Figure 1), conducted during 2020 and 2021, involved a collaborative multi-step process led by research teams at the University of Auckland and Deakin University. Both teams had extensive experience in developing and applying indicators for assessing food company practices as part of INFORMAS. Firstly, we conducted a literature review to identify existing sustainability reporting frameworks and initiatives that benchmark the food industry. Secondly, we conducted a series of consultations with a range of academic experts on the draft set of indicators. Thirdly, we conducted three in-depth interviews with major food companies in New Zealand to gain insight into the implementation feasibility from a food industry perspective. The entire process was iterative, with the indicators and questions for experts revised after each step.

Figure 1.

Iterative process to develop the proposed set of environmental sustainability indicators for food companies.

2.2. Literature Review to Identify Existing Corporate Reporting Frameworks and Benchmarking Initiatives Related to Environmental Sustainability

We conducted a review of existing corporate reporting frameworks and food industry benchmarking initiatives related to environmental sustainability, and compiled an inventory of the existing indicators that have been used or proposed to assess the environmental sustainability performance of food companies. Reporting frameworks included both mandatory and voluntary standards or guidelines for industry to report on their practices according to specific indicators. Benchmarking initiatives were those conducted by external organisations (e.g., non-government organisations and/or advocacy groups) to assess commitments and/or actions against the indicators, and sometimes compared the performance of companies with one another. If no suitable indicators existed in particular topic areas, the review sought to identify the relevant recommendations for food companies from authoritative bodies that could be adapted into suitable metrics.

The review included both academic literature and grey literature, up to and including July 2021. Key environmental science databases (Agriculture and Environmental Science Database and Web of Science) and Google Scholar were searched. Search concepts included “food and environmental sustainability” (including the topic areas, such as energy and water usage, defined as in scope for this study); “indicators” or “benchmarking frameworks”; and “corporate” or “business”. An internet search was conducted using the Google search engine, supplemented by direct searches for initiatives of which the researchers were already aware. Indicators selected included those specific to the food industry and those designed to apply to multiple industries or sectors. Particular attention was paid to indicator frameworks that included domains such as sustainable food sources, energy, water use, food waste and packaging, as these were considered particularly relevant to the aims of the study. In identifying the domains, we were guided by well-established frameworks, such as GRI [18], and benchmarking initiatives, such as the World Benchmarking Alliance [34], as underpinned by the Sustainable Development Goals [14].

2.3. Develop a Draft Set of Indicators and Associated Scoring Criteria

For each topic area (referred to as “domains”), we sought to develop a set of indicators, scoring criteria and a good-practice statement for the domain overall. Where relevant, corresponding Sustainable Development Goal(s) for each domain were identified. Based on the literature review, we developed a set of indicators using an iterative process, involving extensive discussion within the research team guided by the literature and previous expertise in designing and implementing indicators for assessing food company performance. Proposed scoring criteria were developed based on the existing BIA-Obesity scoring method [27]. Under this method, companies are allocated points (e.g., out of a maximum of 10) for each indicator based on their performance against good practice. Where relevant, the scoring incorporated assessment of whether relevant company commitments were SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based). In order to evaluate a company’s impact across its supply chains, scoring was adjusted to take into account the extent to which commitments and/or performance measurement included consideration of the activities of the company’s suppliers, such as if a supplier measured energy consumption. Scoring for indicators related to company reporting including consideration of the frequency of reporting, whether it was publicly available, externally audited, and whether measurement relied on well-established tools and frameworks.

2.4. Consultation on Draft Set of Indicators

Three rounds of consultation on the draft set of indicators and associated scoring criteria were conducted. These consisted of feedback with academic experts, interviews with food company representatives, and targeted consultation with a team of experts convened by INFORMAS (Food Sustainability Advisory Team). Each round of consultation is described in more detail below. Ethical consent was gained for the interviews from The University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee on 8 June 2020 (024751).

2.5. Feedback from Academic Experts

Feedback on the draft set of indicators and associated scoring criteria was sought from experts in environmental sustainability in an iterative process. The draft set of indicators were sent to seven academic experts in New Zealand and Australia known to the research teams through food sustainability networks and other contacts. Six experts provided feedback. Their expertise covered urban and rural food production and consumption, sustainable refrigeration, energy use, packaging, sustainable food systems, sustainable assessment and modelling, water resources management and biodiversity. Experts were asked for general feedback on the terminology used, their feasibility of implementation, and the extent to which company policies and activities related to each indicator was likely to contribute to improved environmental sustainability. Experts were also asked specific questions on indicators relevant to their areas of expertise (Supplementary File S1: List of questions for academic experts and food company representatives).

2.6. Interviews with Food Companies on Implementation Feasibility

Representatives from nine food companies based in Australia and/or New Zealand were invited to participate in an interview to provide feedback on the relevance of the indicators to their operations and the feasibility of their implementation (e.g., with respect to measurement and reporting) in practice. Three food company representatives from three companies accepted the invitation: a large supermarket retailer, a large multinational food manufacturer and a multinational quick-service restaurant. An employee responsible for sustainability was interviewed from each company (interview duration 45–60 min). Interviewees were asked for their initial impressions of the draft set of indicators, their relevance to their sector, the likely feasibility of their company reporting on the indicators and any gaps. The interviews also explored perspectives on the extent of influence their company could have on the environmental sustainability practices of their supply chains. The interviews were audio recorded with the interviewee’s permission and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis of the interviews was undertaken by one researcher, with a second researcher reviewing the themes in an iterative way.

2.7. Consultation with the INFORMAS Food Sustainability Advisory Team

In 2021, INFORMAS assembled an international Food Sustainability Advisory Team (Food-SAT) to advise on the incorporation of environmental sustainability metrics as part of the INFORMAS activities. The INFORMAS Food-SAT comprised 18 global academic experts in sustainable diets. All members of the Food-SAT were invited to provide feedback on the proposed set of indicators, with specific questions for the Food-SAT shaped by earlier feedback from the academic experts and input from the interviews with food companies. The draft indicators and questions were sent to the Food-SAT members and then discussed at an online meeting of the Food-SAT in July 2021 (attended by 14 Food-SAT members). Questions focused on their overall impression of the proposed set of indicators; the need for the proposed set of indicators; ways to best account for differing food company areas of operation, impact and priorities; proposed scoring criteria; and ways to consider a company’s impact and influence on food supply chains. The key considerations were identified and thematically analysed by one researcher with a second researcher reviewing the themes.

2.8. Refinement of Proposed Set of Indicators and Implementation Considerations

At each step, the feedback from the academic experts, food industry and Food-SAT was discussed by the research team to inform the selection of indicators, the content and wording of the indicators and the scoring criteria. Based on the feedback received, indicators were added, amalgamated or deleted, definitions strengthened, suggestions incorporated into scoring and minor wording changes made. Where the nature of the feedback was high-level, rather than applying to individual indicators, or to those that could not be accommodated through the way the indicators were specified, we noted these as implementation challenges and considerations. As part of this analysis, we clearly differentiated between feedback from industry and from academic experts.

3. Results

3.1. Existing Reporting Frameworks and Benchmarking Initiatives

3.1.1. Reporting Frameworks

Existing reporting frameworks relevant to the assessment of the environmental sustainability of companies are outlined in Table A1. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [18] provides a framework for companies to self-report their environmental, social and economic sustainability, and is the most widely used environmental sustainability reporting framework [7]. GRI standards are designed to be used by any industry, with sector-specific standards for certain industries with a particularly high environmental impact, including agriculture and fishing. The indicators in the GRI standards were developed by consensus from a broad range of stakeholders [35,36], and are generally considered to be the de-facto international standard for environmental sustainability reporting [35,37,38,39]. Limitations of GRI relevant to this research are that the GRI’s focus on internal organisational performance largely ignores metrics related to an organisation’s interactions with local ecological systems [37,40] and, arguably, discourages integrated thinking about the trade-offs between various indicators, particular where there may be conflict between financial, social and environmental performance [40]. Critics of GRI standards recommend that a company should be required to categorise data related to particular indicators by geographic region and specific sites [37,40,41]; that scoring and weighting of indicators be included as part of the standards; and that a public database of historical data be established to enable tracking of progress against the targets [37].

We identified other voluntary reporting frameworks and tools that apply across multiple different aspects of environmental sustainability, with slightly different target audiences (Table A1). Two prominent frameworks, the SAM Corporate Sustainability Assessment (which benchmarks corporate performance on economic, environmental and social topics) and the CDP Disclosure Insight Action (which facilitates corporate disclosure on environmental topics like climate change), are both predominantly targeted towards investors as end users [20]. Most frameworks and tools covered all industries, although some had specific indicators for the food industry. For example, the Food Loss and Waste Accounting and Reporting Standard [23] provides guidance for food companies to identify and quantify food loss and waste in their supply chain. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) [42] provides industry-specific sustainability accounting standards for companies to disclose information to investors on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues likely to have a financial impact, including specific ESG indicators for food and beverage companies. The Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture systems (SAFA) [43] specifies guidelines for reporting the environmental and social sustainability of food and agriculture supply chains. The focus of some frameworks and tools, such as the UN Global Compact [21], is very broad, covering human rights to the environment. Other indicator systems address more specific elements of environmental sustainability, for example packaging (Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation Sustainable Packaging Guidelines) [44] or greenhouse gas emissions (Greenhouse Gas Protocol) [45].

Across the wide range of existing frameworks and tools, we identified the relevant indicators across all of the domains included in the study, except for the animal-sourced foods domain. For this domain, we used the EAT-Lancet guidelines for healthy sustainable diets [3] as guidance in developing draft indicators. Within each domain, the number of indicators varied across the various frameworks and tools, with similarly large variation in the aspects included and the level of detail required to be reported.

3.1.2. Existing Benchmarking Initiatives

We identified several initiatives that benchmark food companies’ environmental sustainability commitments and reporting. Behind the Brands [33] was one of the earliest, first developed in 2013 by Oxfam, that benchmarked the largest ten food and beverage companies on their environmental and social policies critical to sustainable agricultural production. Behind the Brands provided external assessment of companies’ sustainability performance, but only assessed global brands, did not include retailers or restaurants (fast food) and relied on companies’ publicly available commitments. The last benchmarking assessment was in 2016 [46].

Since then, the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) [34] developed publicly available benchmarks to rank a selection of global food and agricultural companies on their contributions to achieving and stimulating action towards the SDGs. In 2020, the WBA undertook a baseline assessment of the commitments to the environment, nutrition, social inclusion, governance and strategy of 350 of the most influential companies across the global food and agriculture value chain [34]. Forty-five indicators were assessed, including 12 related to environmental sustainability. The global focus means that, at the country level, many large and influential food companies were not assessed.

Plating Up Progress [47], conducted by The Food Foundation in the United Kingdom (UK), is one of the few relevant initiatives that has taken a country-level approach. Using metrics aligned with those proposed by WBA, Plating Up Progress benchmarks consumer-facing, food-related companies such as restaurants, caterers and supermarkets across key themes relating to the transition to a healthy and sustainable food system. Publicly available information is fact-checked through engagement with companies. A 2020 report mapped the current commitments, targets and performance of 11 UK supermarket chains and 15 UK food-service chains. A traffic-light score was provided for each company across ten topics, seven related to environmental sustainability (across 16 indicators). Thus far, Plating Up Progress has only been implemented in the UK, and it focuses on food-service and retail companies, not food producers and manufacturers.

3.1.3. Proposed Set of Indicators and Associated Scoring Criteria

Based on the existing reporting frameworks, benchmarking initiatives and feedback from various stakeholders, we developed a set of 37 proposed indicators categorised into ten domains (Table 1). The scoring criteria were refined, with additional points added if the company committed to focus on area(s) or suppliers of the highest risk and regularly reported annually on measurable indicators such as emissions, water withdrawal and energy use. The domains were corporate sustainability strategy, packaging, greenhouse gas emissions, energy use, water and discharge, biodiversity, food loss and waste, environmental compliance, animal-sourced foods and relationships with other organisations. The relationship of each domain to relevant Sustainable Development Goal(s) was identified (Table 1). Each domain pertains to the three different sectors (manufacturing, quick-service restaurants and retail). As an example of the scoring criteria, for the indicator “Does the company and its supply chain have a commitment to locally relevant recovery pathways for packaging?”, a company would receive 2 points for each relevant company commitment that is publicly available, specific, measurable and time-bound (to a total maximum of 10 points for the indicator). If a particular commitment did not meet all of the SMART criteria (e.g., was not time-bound) or was not publicly available, then only 1 point would be allocated. Additional points (within the maximum points for each indicator) were allocated if there was an explicit focus on highest-risk suppliers or aspects of the indicator.

Table 1.

Domains, good-practice statements, indicators and related Sustainable Development Goals.

3.2. Key Considerations and Challenges for Implementation

3.2.1. Overall Feedback

The academic experts (including members of the Food-SAT) and food company representatives that participated in the interviews all noted the complexity of setting company-specific commitments and measuring performance in relation to environmental sustainability, and they highlighted multiple challenges for implementation of the proposed set of indicators.

The academic experts considered the set of indicators to be comprehensive and noted that they addressed many of the current gaps and deficiencies in the existing reporting standards and relevant benchmarking initiatives. In particular, they valued that the indicators were developed specifically for the industries of interest (food and beverage manufacturers, quick-service restaurants and retailers) and included a comprehensive set of indicators tailored to these industries. While the academic experts consulted recognised the value of developing the indicators for large corporations, they highlighted the need to ensure that appropriate standards and metrics are developed for small to medium enterprises. Interviewees noted that company structure (e.g., ownership structure and legal status) can have an influence on the extent of change feasible in the short term, and the degree of control a company has on its operations in different contexts. For example, changes are implemented differently if a quick-service restaurant is owned by the company rather than a franchisee. Interviewees noted that multinational companies could be expected to imbed environmental sustainability throughout their company but needed their actions to be specifically tailored to differing environmental and legal priorities in different countries.

Academic experts noted that many of the proposed indicators are focused on the stated intent of the company (e.g., commitments) rather than the impact of the company’s activities (e.g., by assessing the extent to which commitments are being implemented/acted on). While they noted the value of assessing policies and commitments, they indicated that assessment of performance was imperative. In response to this feedback, we ensured that the proposed set of indicators also included a wide range of indicators focused on measuring actual practices. Academic experts noted that measurement of performance in relation to many of these indicators would rely on robust methods and tools for quantitative assessment. They raised concern that, in many areas, there was wide diversity in the measurement tools used by companies, a lack of consensus on appropriate measurement methods and likely to be a lack of capacity for implementation of measurement tools, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

3.2.2. Supply Chain

All stakeholder groups consulted noted the importance of including an assessment of the impact of a company’s suppliers (and, in some cases, the broader supply chain) as part of an assessment of individual companies but acknowledged that such an assessment is challenging to implement in practice. Academic experts noted that, as a starting point, a company could be expected to identify and engage with ‘high-risk’ suppliers (e.g., those with the largest potential impact) on environmental sustainability issues. Academic experts suggested to recognise in the scoring criteria the extent to which the company identifies and prioritises actions related to high-risk suppliers, and for relevant domains (e.g., in relation to ‘packaging’ and ‘energy use’) to focus on the proportion of suppliers that are reported to be taking relevant actions. Participants acknowledged that small-scale suppliers are unlikely to have the knowledge or technology to provide the information required for assessment. Food company representatives agreed that they needed to be aware of supplier commitments; that companies can influence their suppliers; and that companies needed to have specific strategies across the supply chain in relation to ‘high-risk’ products, such as palm oil. However, they believed that it is not practical to address every aspect of environmental sustainability with every supplier.

3.2.3. Priority Actions

All stakeholders identified that, to get the most beneficial environmental impact, it is important for companies to focus on areas where the most gains can be made, rather than trying to achieve best practice across all indicators in the short term. They noted that priority areas will depend on the nature of a company’s business, product portfolio, areas of operation, geography, climate and other local contextual factors. For example, a supermarket is likely to have the most impact on energy use by ensuring an efficient refrigeration system. This feedback was reflected in several ways in the proposed set of indicators. For example, an indicator was included in the ‘corporate sustainability strategy’ domain regarding whether the company identifies and prioritises for action the issues that are likely to have the most impact on the environment. In addition, the scoring criteria provide points if a company was focusing on the highest risk areas.

Academic experts agreed that weighting of domains and particular indicators is important in assessing a company’s overall environmental sustainability credentials, but noted that such weightings should be specific to each sector and/or sub-sector (e.g., soft drinks and dairy), and may need to be tailored to each company depending on the nature of their operations. For example, a company for which high water usage and discharge were identified as the major contributors to their environmental impact, would require a higher weighting for the water domain than a company for which energy use was identified as the major impact area.

Participants also commented on the potential ‘trade-offs’ between indicators as part of an overall assessment of company performance on environmental sustainability. For example, the use of hydro-dams typically provides a sustainable source of energy but can have negative impacts on biodiversity. The comprehensive nature of the set of indicators was likely to ensure that such trade-offs were captured to some extent, although the way this plays out in practice would need to be investigated.

Finally, both academic experts and food industry representatives noted that several indicators may not be applicable to particular companies, due to considerations such as the nature of their operations or geographic location. For example, the indicators relating to areas of water stress would not apply to a region with high, consistent rainfall. Stakeholders noted that the way the set of indicators are tailored to particular companies and industry sub-sectors needs to be tested. In addition, they noted that the extent to which company-specific weighting of indicators affects the ability to compare company performance, both within and across sectors, needs to be explored.

3.2.4. Specific Domains

Participants considered ‘packaging’ to be one of the most straightforward domains on which companies can report. They highlighted that companies are often required to make trade-offs in this area, for example, between concerns around food safety, food loss and sustainability of packaging. In relation to the ‘food loss and waste’ domain, food company representatives identified there are financial benefits for companies to minimise food loss and waste, though much of the opportunity to minimise food loss and waste typically occurs early in the supply chain (before the product gets to the manufacturer or retailer). They flagged that reporting on such activities across the supply chain could be challenging for individual food manufacturers or retailers.

Food company representatives suggested that the ‘greenhouse gas emissions’ and ‘energy use’ domains be combined since companies tend to commit to reducing carbon emissions by reducing energy use and changing the source of energy. However, there was consensus amongst academic experts that these domains should remain separate as they highlight different focus areas, and so were not combined. It is recommended that all company reporting on greenhouse gas emissions should clearly differentiate between Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions [48]. All stakeholders discussed that ‘water use and discharge’ can vary substantially, depending on the sector, type of company and seasonal weather patterns, and so the highest priority indicators for a company will likely differ and some may be not applicable to particular companies.

Academic experts and food company representatives acknowledged that the ‘biodiversity’ domain is particularly challenging due to its broad coverage. Academic experts suggested that the scope of this domain be narrowed to focus on specific aspects of biodiversity, such as deforestation, impact on preservation of species and varieties, and control of the origin of raw materials or livestock. Food company representatives commented that consideration of biodiversity can greatly depend on the characteristics of the supply chain. Some participants suggested that indicators in this domain should be about companies assessing risk and taking action to manage the risk. Participants indicated that the ‘biodiversity’ domain warrants a lower weighting than other domains due to the challenges in defining its scope and measurement.

Academic experts commented that the domain on ‘animal-sourced foods’, while critically important due to the substantial contribution of animal foods to the environmental sustainability of food systems, proved challenging in identifying appropriate indicators at the company level, particularly due to the different types and levels of processing of animal-sourced foods. Experts recognised the lack of applicable standards and benchmarks in this area. Academic experts and food company representatives agreed that assessing the greenhouse gas emissions of all products, with a focus on reducing the impact of production of animal foods, was a higher priority area of focus than company efforts to introduce a greater number of plant-based options. Academic experts commented there is a danger that introduced plant-based options were not always healthy (e.g., they are often ultra-processed and high in sodium, sugar and/or saturated fat). Furthermore, in some countries, access to animal foods is considered positive for nutrition. In recognition of this feedback, indicators focused on the assessment and reduction of emissions of all products were included in the ‘greenhouse gas emissions’ domain, and could be expected to receive a relatively large weighting as part of an overall assessment of company performance. An indicator related to reducing animal-sourced foods was removed for manufacturers but remained for quick-service restaurants and retailers. Retailers and quick-service restaurants could reasonably be expected to offer a diverse range of products, including plant-based options, whereas many food and beverage manufacturers, such as processed meat manufacturers, typically have more specialised product portfolios.

With respect to the domain on ‘relationships with other organisations’, stakeholders noted that there were typically many opportunities for companies to engage with relevant groups, roundtables and coalitions, with the potential for greater impact through collaboration. However, academic experts noted the difficulty in determining how actively engaged individual companies are as part of such groups. They stressed that transparency from companies regarding their involvement with other organisations was critically important, especially in relation to the corporate political activity (e.g., lobbying, political donations and research funding) of companies. Food companies noted that voluntary commitments to collaborate and participate in existing initiatives was important to recognise, but academic experts cautioned that recognising these may contribute to the weakening or delaying of implementation of the recommended mandatory policies by governments, as has occurred in relation to nutrition [12,49].

4. Discussion

This study developed a proposed set of indicators for assessing the commitments and practices of food manufacturers, quick-service restaurants and retailers regarding environmental sustainability. We proposed a set of 37 indicators across ten domains, based on the indicators used in existing reporting frameworks and benchmarking initiatives as well as extensive feedback from subject matter experts. The study also identified key considerations for applying these indicators in practice, including the importance of identifying company- and sector-specific priority areas for action, inclusion of a company’s impact across the supply chain and accounting for differences in sectors and geographic locations as part of the reporting and assessment.

The proposed set of indicators is designed to be applied at the national level to assess the environmental sustainability commitments and practices of the most prominent food companies in each country. In principle, the proposed set of indicators can also be applied to compare the performance of multi-national companies and of sectors across countries. Where implemented as part of the global INFORMAS network, it is recommended that application of the proposed set of indicators in a particular country be conducted in line with the existing BIA-Obesity process that has been successfully implemented in multiple countries to assess the nutrition-related policies and practices of major food companies [27,50]. As part of national-level implementation, the proposed set of indicators are designed to be adapted for the local context, including the specific environmental and regulatory context of each country. For example, in a country of high water stress, the indicators may be adapted to put more emphasis on the ‘water use and discharge’ domain. Importantly, the way in which the proposed set of indicators are applied in practice, including feasibility and utility, needs to be tested in a range of countries.

The proposed set of indicators are drawn from, and align strongly with, other existing indicators, including the relevant GRI standards and relevant reporting frameworks [35,36,37,38] and similar benchmarking initiatives, such as those developed by the World Benchmarking Alliance, the Food Foundation and Oxfam [33,34,47]. The proposed set of indicators are tailored to the sectors on which we focused and incorporate a wide range of domains commonly identified as important for comprehensively addressing environmental sustainability. While in some areas, such as soil health and agrobiodiversity, fertiliser and pesticide use, our indicators are not as comprehensive, detailed and specific as those in other tools, our indicators are designed to require relatively limited resources to assess, and encourage a multifaceted approach to assessing environmental sustainability.

In line with the objectives of INFORMAS [26], the indicators are designed to be applied by a small research team on a regular basis (e.g., every second year) in a particular country to compare company performance and monitor changes in company commitments and practices over time. This approach is similar to the recommended approach of the WBA Food Foundation toolkit (WBA/FF) [51], introduced at the end of 2021, which outlines methods to benchmark food companies at the national level in four areas: governance and strategy; environment; nutrition; and social inclusion. The WBA/FF toolkit has a broader scope, organized into six value chain sectors, of which three are upstream sectors (agricultural inputs, agricultural producers and commodities, and animal proteins) not covered in our approach. Both initiatives include downstream sectors (food and beverage manufacturers, food retailers and quick-service restaurants). The environmental indicators in the WBA/FF toolkit and the previous Behind the Brands cover a similar set of domains to those proposed in this paper, such as packaging, greenhouse gas emissions, water, biodiversity, food loss and protein diversification. The WBA/FF indicators have more of a focus on ecosystems preservation as well as on-farm levers such as pesticide use. While both toolkits cover governance, the indicators in our tool concerning corporate oversight and relationships with stakeholders are more comprehensive. As our proposed tool has fewer indicators and domains than this recent benchmarking initiative and the earlier Behind the Brands initiative, it is suitable for a country with limited resources. Our tool is focused on environmental sustainability and may warrant implementation in conjunction with other tools to ensure broader coverage of relevant ESG issues, such as Fair Trade Certification in relation to labour and gender equality [52] and the World Benchmarking Alliance human rights and animal welfare benchmarks [51]. As new tools and approaches are applied and tested, we expect that a convergence of benchmarking tools will evolve. This highlights the need for greater harmonisation of metrics and reporting guidelines.

4.1. Implications

Assessment of food companies using the set of metrics proposed in this study can help strengthen efforts to improve accountability for action to improve the environmental sustainability of food systems. The primary potential users of the proposed set of indicators include researchers and environmental sustainability advocates in: articulating the expectations of food companies in relation to environmental sustainability; taking account of food company actions in the area by monitoring and benchmarking their performance; and, assisting efforts to hold food companies to account for the impact of their operations on the environment. Furthermore, application of the proposed set of indicators can build local knowledge and research capacity regarding the environmental sustainability of food systems, as well as networks and dissemination systems within and across countries to conduct benchmarking in this area [53]. The proposed set of indicators are also likely to be useful for food companies and investors, particularly those focused on sustainable investment. The indicators can be used alongside other corporate reporting frameworks and benchmarking initiatives relevant to food companies. For example, the proposed set of indicators could complement nutrition-related benchmarking initiatives such as Access to Nutrition Initiative (ATNI) [54] and BIA-Obesity [17]. Application of the proposed set of indicators is likely to provide important information for governments in assessing the effectiveness of regulations regarding environmental sustainability and related reporting.

Critically, assessment of company performance is only as good as the standard of information collected and reported by companies. Across the board, capacity building regarding measurement tools and related expertise is likely to be required to enable reliable reporting against many of the indicators that rely on rigorous measurement. Ideally, the reporting requirements (including detailed specification of measurement techniques and requirements) would be mandatory to ensure that consistent quality reporting is adopted across all relevant companies. In this regard, the European Union (EU) has recently agreed to mandate the ESG reporting requirements as part of the ‘EU Green Deal’ [55]. The EU ‘Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive’ (2021) requires all large and listed companies to report on sustainability-related factors that affect the company, including how the company impacts on the environment [55]. As well as being mandatory, reporting will be audited in order to bring sustainability information in line with existing requirements for financial information. In New Zealand, legislation was passed in 2021 to make climate-related disclosures mandatory for some organisations [56]. As standards and measurement tools for particular indicators related to environmental sustainability improves, the reliability of the assessment will strengthen.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study are that the proposed set of indicators bring together metrics from existing initiatives for a comprehensive approach to assessment of company performance with regards to environmental sustainability. We engaged in detailed consultation to inform the development of the proposed set of indicators, including feedback from academics with a wide range of relevant expertise and consultation with food companies regarding the feasibility of implementation. The iterative development meant revisions to the indicators could be made at each stage of consultation. Important implementation considerations gleaned from the consultation process have been identified and can be explored as part of the implementation testing.

The study had several limitations. First, while we set out to adopt a comprehensive approach to assess the environmental sustainability of food companies, the multifaceted and complex nature of environmental sustainability means it is challenging to define a feasible scope for implementation. We conducted a comprehensive literature review; however, the field of environmental sustainability is rapidly developing and so it is possible that we were not able to capture all the relevant frameworks, particularly those found outside of the academic literature. While we consulted extensively with academic experts in the field of environmental sustainability, due to the wide range of specialist subject areas in the field, we were not able to consult with experts in all subject areas. We selected ten domains for inclusion and settled for breadth rather than depth in each domain, in order to ensure inclusion of a broad range of domains. We recognise that indicators in related domains, such as animal welfare and gender equality, could be included or used in conjunction with the proposed set of indicators as part of a detailed assessment. Second, as part of the study, we did not specify any detailed measurement requirements for individual indicators (e.g., related to measurement tools and protocols). Future research should aim to specify such detail.

Third, the implementation of the proposed set of indicators has not yet been tested in practice so the extent to which the proposed set of indicators are useful as a benchmarking tool is unclear. For example, it is important that the indicators are able to recognise good practice and provide sufficient differentiation between companies on their performance. These aspects need to be examined as part of the implementation testing in a range of countries and types of food companies. Such testing should include development of geographic- and sector-specific weightings for each domain; detailed scoring guidelines; and the feasibility, quality and consistency of a company’s reporting against each indicator. Importantly, preliminary feasibility testing (conducted in relation to five companies based in New Zealand) indicates that companies do publicly provide information on many of the indicators, though less so for some domains, such as ‘biodiversity’. Testing could also include the feasibility of implementing the proposed set of indicators alongside existing nutrition indicators (such as using the BIA-Obesity tool).

Fourth, the study focused on indicators for large companies, but it is well recognised that small and medium enterprises typically play a major role in food systems and have a substantial impact on their environmental sustainability [57,58]. Future research should explore suitable metrics that could be applied in relation to the resources available to small and medium enterprises.

5. Conclusions

The proposed set of 37 indicators across ten domains provides a clear indication of environmental sustainability best practice for food and beverage companies (manufacturers, quick-service restaurants and retailers) at a national level. The proposed set of metrics can contribute towards a holistic approach to assessing a company’s contributions to addressing food system issues, particularly when combined with nutrition-related assessment tools, such as BIA-Obesity. Pilot testing is proposed to test the feasibility and usefulness of applying the set of indicators in a range of countries and contexts, including assessment of a company’s environmental sustainability impact across the supply chain, refining the scoring criteria for each indicator, and the weighting of indicators based on company- and sector-specific priority focus areas. Assessment of food companies using the proposed set of metrics can be used to improve accountability for action and inform government regulatory responses in this area.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su141610315/s1, File S1: List of questions for academic experts and food company representatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and G.S. (Gary Sacks); methodology, S.M., G.S. (Gary Sacks), A.R.-D. and E.R.; formal analysis and investigation, S.M., G.S. (Gary Sacks), E.R., G.S. (Grace Shaw), A.R.-D. and E.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M., G.S. (Gary Sacks), A.R.-D.; writing—review and editing, S.M., G.S. (Gary Sacks), E.R., G.S. (Grace Shaw), A.R.-D. and E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Auckland, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, FRDF (Faculty Research Development Fund) New Staff grant (#3720346) “Monitoring the sustainability and healthiness of the products of major New Zealand Food Companies”. The study also formed part of an International Development Research Centre (IDRC) funded project entitled “Towards harmonized indicators for measuring progress on creating healthy and sustainable food systems”. GS is a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Fellowship (2021/GNT2008535) and a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (102035) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Participants Ethics Committee of The University of Auckland (protocol code 024751 on 8 June 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bruce Kidd (University of Auckland) for assistance with developing the indicators and scoring criteria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Existing environmental sustainability reporting frameworks and benchmarking initiatives.

Table A1.

Existing environmental sustainability reporting frameworks and benchmarking initiatives.

| Organisation | Description | Audience Purpose | Funding | Industries Included | Domains | Themes or Indicators Related to Environment | # of Environmental Indicators | # Companies Participating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting Frameworks | ||||||||

| Global Reporting Initiative [18] | Helping businesses and government understand and communicate their impact on critical sustainability issues | Companies themselves Tool for companies to self-report their environmental practices and outcomes | Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency Swiss State Secretariat UK Aid Australian Aid Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Alcoa Foundation Fundacion ONCE | All industries | Economic, environmental, and social sustainability | Materials Energy Water and effluents Biodiversity Emissions Environmental compliance Supplier environmental assessment | 91 indicators | 82% of world’s largest companies use GRI standards |

| Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation Sustainable Packaging Guidelines (SPGs) [44] | SPGs are part of the co-regulatory framework established by the National Environment Protection Measure 2011 and Australian Packing Covenant 10 principles | Business, NGOs, government, individuals Large businesses are a signatory to the Covenant or need to meet compliance obligations related to packaging | Not-for-profit membership fees | All industries | Packaging | Packaging recovery Material efficiency Reduce waste Eliminate hazardous materials Use recycled or renewable materials, Minimise litter Transport efficiency Accessibility | 10 principles, 13 criteria (six are design related) | APCO members are required to work towards achieving principles and report on actions |

| Climate Disclosure Standards Board [59] and CDP [20] | Global disclosure system for investors, companies, cities, states and regions to manage their environmental impacts | Companies, investors, cities, states and regions Annual scorecard based on companies self-reporting their practices | Philanthropic grants, service-based membership, government grants. Full list not currently available. | All industries | Climate change, water security, deforestation. | Governance Climate-related risks and opportunities Business strategy, targets and performance Emissions methodology Emissions data Energy-related activities Additional metrics Third party verification of emissions data Carbon pricing Value chain engagement on climate-related activities | Different indicators for different sectors and company sizes | No information found |

| Food Loss and Waste Reporting Standard [23] | Reporting standard for quantifying food and associated inedible parts removed from the food supply chain | Companies, countries and cities Guideline for companies to self-report their food loss and waste | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Ireland, Walmart Foundation | Any for which food loss is relevant | Guidelines for quantifying all food loss and waste in supply chain | Food loss Food waste | No specific indicators | No information found |

| Greenhouse Gas Protocol [45] | Global standardised frameworks to measure and manage greenhouse gas emissions from private and public sector operations | Companies, countries and cities Guidance for companies to self-report their greenhouse gas emissions | Philanthropic organisations, government and companies, including Ford, General Motors, Shell, Toyota | Greenhouse gas emissions. All industries | Greenhouse gas emissions | Greenhouse gas emissions | No specific indicators | No information found |

| Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture [43] | Guidelines for self-evaluation about environmental and social sustainability of food and agriculture supply chains | Food and agriculture enterprises NGOs and sustainability standards and tools community Governments, investors and policy makers Assess the impact of food and agriculture operations on the environment and people | Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) | Crop, livestock, forestry, aquaculture and fishery value chains | Governance Social Environment Economy | 21 Themes (universal sustainability goals) 58 sub-themes (specific to supply chains) | 116 | No information found |

| SAM Corporate Sustainability Assessment [19] | Questionnaire and benchmarks for investors who want to reflect sustainability in their investment portfolios | Investors Questionnaire tool for companies to self-report their environmental practices and outcomes | S&P Global | All industries | Three dimensions: economic, environmental and social | Operational eco-efficiency Climate strategy Product stewardship | 82 indicators | 3,500 of largest publicly traded companies invited to participate. |

| Sustainability Accounting Standards Board [42] | Provides industry-specific sustainability accounting standards for companies to disclose their environmental, social and governance sustainability financial information to investors | Investors Sustainability financial information for investors | Value Reporting Foundation Not-for-profit | All industries (77 industry standards) Specific indicators for agricultural products, alcoholic beverages, food retailers and distributors, meat/poultry and dairy, non-alcoholic beverages, processed foods, restaurants | Environmental, social, governance sustainability financial information | Disclosure topics and accounting metrics vary according to industry. Examples include: Energy management Water management Supply chain management Food packaging and food waste management Ingredient sourcing Air emissions from refrigeration | Each standard has six disclosure topics and 13 accounting metrics | No information found |

| Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures [60] | Recommendations | Investors, lenders and insurers Provides guidance for more effective climate-related financial disclosures | Taskforce reports to Financial Stability Board, Bank for International Settlements | All industries | Recommendations: Governance Strategy Risk management Metrics and targets | There are recommended disclosures and guidance for each of the four recommendations | 11 disclosures | No information found |

| United Nations Global Compact [21] | Principles for CEOs to voluntarily commit to sustainability practices | Companies Sustainability principles that companies can sign up to commit to | Governments of China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK Over 1,500 businesses | All industries | Human rights Labour Environment Anti-corruption | Climate change Water and sanitation Ocean stewardship | Three principles | 10,452 companies in 161 countries |

| Benchmarking Initiatives | ||||||||

| World Benchmarking Alliance [34] | Free, publicly available benchmarks which rank companies on their contributions to achieving the SDGs | Empowering consumers, investors, governments and civil society organisation to decide where to spend their money, allocate their investments or direct policy and advocacy efforts Benchmarking companies’ environmental practices and outcomes | Aviva Governments of the Netherlands, UK, Denmark | Agricultural inputs, agricultural products and commodities, animal proteins, food and beverage manufacturers/processors, food retailers, restaurants and food service | All SDGs Domains include environment, nutrition, social inclusion, governance and strategy | Greenhouse gas emissions Land use Water use Nitrogen and phosphorous use Biodiversity loss Food loss and waste | 12 environmental indicators | 350 in initial assessment |

| World Benchmarking Alliance and Food Foundation [51] | Free, publicly available benchmarks which rank companies on their contributions to achieving the SDGs | Investors, businesses, policy makers Benchmarking companies’ environmental practices and outcomes Benchmarks for food and agriculture companies published in December 2021 | See above | Agricultural inputs, agricultural products and commodities, animal proteins, food and beverage manufacturers/processors, food retailers, restaurants and food service | All SDGs Domains include environment, nutrition, social inclusion, governance and strategy | Greenhouse gas emissions Land use Marine use Protein diversification Soil health Fertilizer use Water use Food loss and waste Plastics and packaging Animal welfare | 12 | Toolkit available for other countries and organisations to use |

| Behind the Brands [33] | Part of Oxfam’s GROW campaign Note—has not been updated since 2016 | Consumers and community groups Benchmarking companies’ environmental policies and commitments | Oxfam | Food and beverage companies | Women Small-scale farmers Farm workers Climate change Land Water Transparency | Indicator breakdown not available | Indicators not publicly available | Ten largest food and beverage companies |

| Food Foundation Plating Up Progress [47] | Catalyse and deliver change in food systems through evidence, coalitions, communication and levers for change. | Investors, businesses, policy makers Benchmarking companies’ environmental policies and commitments | Registered charity. Funded by independent charitable trusts, UK aid, independent foundations, National Lottery Community Fund | Supermarkets, casual dining and restaurants, quick service restaurants, caterers, wholesalers (not manufacturers) | Health and nutrition Environment Social inclusion | Climate change Biodiversity Sustainable food production practices Water use Food waste Plastics Animal welfare and antibiotics | 10 topics | 30 UK companies |

References

- Committee on World Food Security and Nutrition. The CFS Voluntary Guidelines on Foods Systems and Nutrition. Making a Difference in Food Security. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/cfs/en (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Shukla, P.R.; Skea, J.; Calvo Buendia, E.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Zhai, P.; Slade, R.; Connors, S.; van Diemen, R.; et al. (Eds.) Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EAT Lancet Commission. Food Planet Health: Summary Report of the EAT Lancet Commission. 2019. Available online: https://eatforum.org/eat-lancet-commission/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Swinburn, B.; Kraak, V.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.; Baker, P.; Bogard, J.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; de Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/global-syndemic (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L.G.; Benton, T.G.; Herrero, M.; Krishnapillai, M.; Liwenga, E.; Pradhan, P.; Rivera-Ferre, M.-G.; Sapkota, T.; et al. Food Security. In Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 439–550. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/chapter-5/ (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Maher, A.; Marta, A.; Cordes, K.; Cresti, S.; Espinosa, G.; Ocampo-Maya, C.; Riccaboni, A.; Rossi, A.; Sachs, L.E.; et al. Fixing the Business of Food. How to Align the Agrifood Sector with the SDGs; Barilla Foundation, UNK Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Columbia Centre on Sustainable Investment, Santa Chiara Lab University of Siena: Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: A global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e451–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.A.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P.; Webb, P. The global and regional costs of healthy and sustainable dietary patterns: A modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e797–e807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. In Brief to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease. Lancet 2017, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Aguirre, E.; Finegood, D.T.; Holmes, C.; Sacks, G.; Smith, R. What role should the commercial food system play in promoting health through better diet? BMJ 2020, 17, m545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialon, M.; Swinburn, B.; Allender, S.; Sacks, G. ‘Maximising shareholder value’: A detailed insight into the corporate political activity of the Australian food industry. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2021. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- INFORMAS. An International Pact on Monitoring for Accountability for Action on Food Systems. 2021. Available online: https://www.informas.org/2021/08/30/an-international-pact-on-monitoring-for-accountability-for-action-on-food-systems/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Kraak, V.; Swinburn, B.; Lawrence, M.; Harrison, P. An accountability framework to promote healthy food environments. Pub. Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2467–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.; Vanderlee, L.; Robinson, E.; Vandevijvere, S.; Cameron, A.J.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Lee, A.; Ng, S.H.; Karupaiah, T.; Vergeer, L.; et al. BIA-Obesity (Business Impact Assessment—Obesity and population-level nutrition): A tool and process to assess food company policies and commitments related to obesity prevention and population nutrition at the national level. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 8–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. About GRI. 2021. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/information/about-gri/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- RobecoSAM. Sustainability Policies and Positions. 2021. Available online: https://www.robeco.com/en/key-strengths/sustainable-investing/sustainability-reports-policies.html (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- CDP. Companies. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdp.net/en/companies (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- United Nations Global Compact. Who Are We. 2021. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- S&P Global. Corporate Sustainability Assessment. 2020. Available online: https://www.robecosam.com/csa/csa-resources/djsi-csa-annual-review.html (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Food Loss and Waste Steering Committee. Food Loss and Waste Accounting and Reporting Standard Version 1.0. 2016. Available online: https://flwprotocol.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/FLW_Standard_final_2016.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Hansen, A.D.; Kuramochi, T.; Wicke, B. The status of corporate greenhouse gas emissions reporting in the food sector: An evaluation of food and beverage manufacturers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, J.; Stubbs, W. Evaluation of Australian companies’ scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions assessments. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kumanyika, S.; Lobstein, T.; Neal, B.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.; et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): Overview and key principles. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, G.; Robinson, E.; Cameron, A.J.; Vanderlee, L.; Vandevijvere, S.; Swinburn, B. Benchmarking the nutrition-related policies and commitments of major food companies in Australia, 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasture, A.; Vandevijvere, S.; Robinson, E.; Sacks, G.; Swinburn, B. Benchmarking the commitments related to population nutrition and obesity prevention of major food companies in New Zealand. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Toronto. BIA-Obesity Canada 2019. 2019. Available online: https://labbelab.utoronto.ca/bia-obesity-canada-2019/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Ng, S.; Sacks, G.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H.; Robinson, E.; Swinburn, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Chinna, K.; Ismail, M.N.; Karupaiah, T. Benchmarking the transparency, comprehensiveness and specificity of population nutrition commitments of major food companies in Malaysia. Global Health 2020, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciensano. BIA-Obesity—Business Impact Assessment on Obesity and Population Level Nutrition. 2021. Available online: https://www.sciensano.be/en/projects/business-impact-assessment-obesity-and-population-level-nutrition (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate change and food systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behind the Brands. Behind the Brands about Us. 2021. Available online: https://www.behindthebrands.org/about/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- World Benchmarking Alliance. Food and Agriculture Benchmark. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/food-and-agriculture-benchmark/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Hoeltl, A.; Brandtweiner, R.; Stock, P.S. Sustainability reports from the food industry: Case studies from Europe and Latin America. Food Environ. 2013, 170, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokos, H.; Pintarič, Z.N.; Krajnc, D. An integrated sustainability performance assessment and benchmarking of breweries. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2012, 4, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhir, L.; Bernard, S.; Abdelgadir, S. Does GRI reporting impact environmental sustainability? A cross-industry analysis of CO 2 emissions performance between GRI-reporting and non-reporting companies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2017, 28, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Tsalis, T.; Nikolaou, I. A new framework for assessing the sustainability reporting disclosure of water utilities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A. Barriers to Strengthening the Global Reporting Initiative Framework: Exploring the perceptions of consultants, practitioners, and researchers. In Accountability through Measurement: CSIN Conference to Advance Best Practices for Sustainability; Canadian Sustainability Indicators Network: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, A.; McAllister, M.L.; Fitzpatrick, P. Sustainability reporting among mining corporations: A constructive critique of the GRI approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, D.M.; Kirsop, P.L.; Meissen, R.E. Global Reporting Initiative Guidelines: An evaluation of sustainable development metrics for industry. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2001, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Value Reporting Foundation. Standards. 2021. Available online: https://www.sasb.org/about/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. SAFA Guidelines: Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems 3.0; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3957e/i3957e.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation. About APCO. 2021. Available online: https://apco.org.au/about-apco (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Corporate Standards. 2020. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/corporate-standard (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Oxfam International. The Journey to Sustainable Food. 2016. Available online: https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/journey-sustainable-food (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- The Food Foundation. Plating Up Progress [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://foodfoundation.org.uk (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Hertwich, E.; Wood, R. The growing importance of scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckler, D.; Nestle, M. Big food, food systems, and global health. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Blake, M.R.; Sacks, G. Benchmarking Food and Beverage Companies on Obesity Prevention and Nutrition Policies: Evaluation of the BIA-Obesity Australia Initiative, 2017–2019. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020, 10, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]