Rethinking Sustainability Hotel Branding: The Pathways from Hotel Services to Brand Engagement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

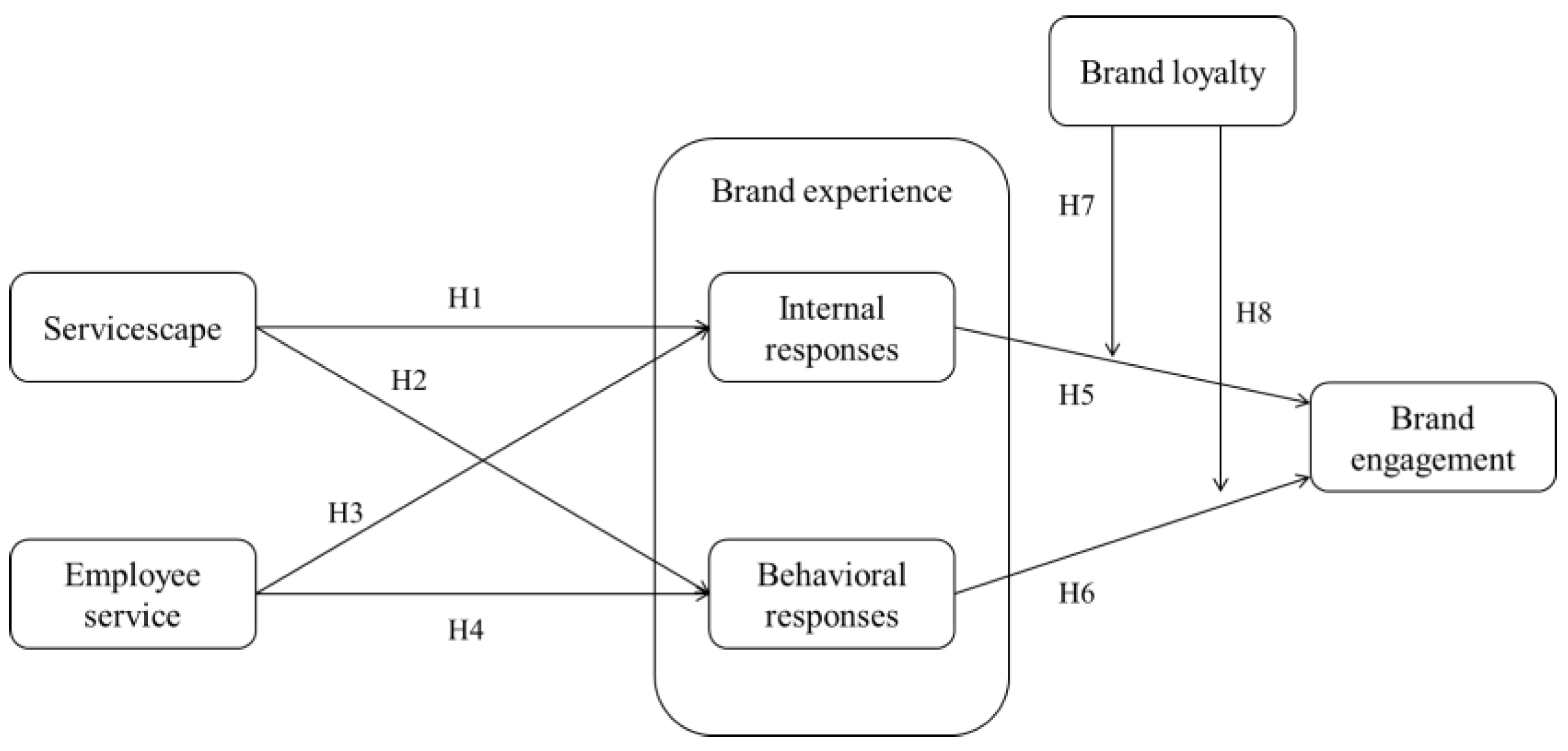

2. Review of the Literature and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Servicescape

2.2. Brand Experience

2.3. Employee Service

2.4. Brand Engagement

2.5. Brand Loyalty

3. Materials and Methodology

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Measures

3.4. Common Method Bias

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Measurement Properties

4.2. Results for the Direct Effects

4.3. The Moderating Effects of Brand Loyalty

4.4. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Servicescape (SS) | |

| SS1 | This hotel has up-to-date facilities. |

| SS2 | This hotel’s physical facilities are visually attractive. |

| SS3 | The appearance of the physical facilities of this hotel is matching with the type of service provided. |

| SS4 | This hotel’s employees have a neat and well-dressed appearance. |

| Employee service (ES) | |

| ES1 | I receive prompt attention from this hotel’s employees. |

| ES2 | Employees here are always willing to help me. |

| ES3 | I can trust the employees of this hotel. |

| ES4 | Employees of this hotel are polite and helpful. |

| Internal responses (IR) | |

| IR1 | This hotel brand makes a strong impression in my visual sense or other senses. |

| IR2 | I find this hotel brand interesting in a sensory way. |

| IR3 | This hotel brand appeals to my sense. |

| IR4 | This hotel brand induces feelings and sentiments for me. |

| IR5 | I have strong emotions for this hotel brand. |

| IR6 | This hotel brand is an emotional brand. |

| IR7 | I engage in physical actions and behaviors when I use this hotel brand. |

| IR8 | This hotel brand results in physical experiences. |

| IR9 | This hotel brand is action-oriented. |

| Behavioral responses (BR) | |

| BR1 | I engage in a lot of thinking when I encounter this hotel brand. |

| BR2 | This hotel brand makes me think. |

| BR3 | This hotel brand stimulates my curiosity and problem-solving. |

| Cognition (CO) | |

| CO1 | Whenever traveling gets me to think about this hotel brand. |

| CO2 | I think about this hotel a lot when I’m using its services. |

| CO3 | Using this hotel’s services stimulates my interest to learn more about its brand. |

| Affection (AF) | |

| AF1 | I feel very positive when I stay at this hotel brand. |

| AF2 | Staying at this hotel brand makes me happy. |

| AF3 | I feel good when I stay at this hotel brand. |

| AF4 | I’m proud to use this hotel brand. |

| Activation (AC) | |

| AC1 | I spend a lot of time using this hotel brand compared to others. |

| AC2 | Whenever I’m traveling, I usually use this hotel brand. |

| AC3 | This hotel brand is one of the brands I usually use when I travel. |

| Brand loyalty (BL) | |

| BL1 | I recommend this hotel brand to other people. |

| BL2 | I say positive things about this hotel brand to other people. |

| BL3 | I will not stop supporting this hotel brand. |

| BL4 | I think of myself as a loyal customer/supporter of this hotel brand. |

References

- Shanti, J.; Joshi, G. Examining the impact of environmentally sustainable practices on hotel brand equity: A case of Bangalore hotels. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5764–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Cultivating service brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Glynn, M.S.; Little, V. The service brand and the service-dominant logic: Missing fundamental premise or the need for stronger theory? Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Dev, C.S. Managing hotel brand equity: A customer-centric framework for assessing performance. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2000, 41, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Dev, C.S.; Rao, V.R. Brand extension and customer loyalty: Evidence from the lodging industry. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2002, 43, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M. Globalization: The Next Phase in Lodging. A Morgan Stanley Report, 5 May 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.B.; Chan, A. A conceptual framework of hotel experience and customer-based brand equity: Some research questions and implications. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 174–193. [Google Scholar]

- Yesawich, P. So many brands, so little time. Lodg. Hosp. 1996, 52, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Arnould, E.J.; Gruen, T.W.; Tang, C. Socializing to co-produce: Pathways to consumers’ financial well-being. J. Serv. Res. 2013, 16, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, M.; van Doorn, J. Coproduction of transformative services as a pathway to improved consumer well-being: Findings from a longitudinal study on financial counseling. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verleye, K.; Gemmel, P.; Rangarajan, D. Managing engagement behaviors in a network of customers and stakeholders: Evidence from the nursing home sector. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T. Customer brand engagement behavior in online brand communities. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B. Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.D. Engagement: The True Currency. 2014. Available online: http://www.dmnews.com/content-marketing/engagement-the-true-currency/article/374871/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Hollebeek, L.D. Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Reinartz, W.J.; Krafft, M. Customer engagement as a new perspective in customer management. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Aksoy, L.; Donkers, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Wiesel, T.; Tillmanns, S. Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijmolt, T.H.A.; Leeflang, P.S.H.; Block, F.; Eisenbeiss, M.; Hardie, B.G.S.; Lemmens, A.; Saffert, P. Analytics for customer engagement. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Baron, R. Interactions in virtual customer environments: Implications for product support and customer relationship management. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Rialp, J. How does sensory brand experience influence brand equity? Considering the roles of customer satisfaction, customer affective commitment, and employee empathy. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Agarwal, J.; Malhotra, N.K.; Varshneya, G. Does brand experience translate into brand commitment? A mediated-moderation model of brand passion and perceived brand ethicality. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, V.; Thomas, S. Direct and indirect effect of brand experience on true brand loyalty: Role of involvement. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 725–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Price, L.; Zinkhan, G.M. Consumers, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zhang, S. Experiential attributes and consumer judgments. In Handbook on Brand and Experience Management; Schmitt, B.H., Rogers, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B. The millennial consumer in the texts of our times: Experience and entertainment. J. Macromarket. 2000, 20, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kang, M.S. The effect of brand experience on brand relationship quality. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2012, 16, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Maiyaki, A.A.; Mokhtar, S.S.M. Determinants of customer behavioral intentions in Nigerian retail banks. Interdiscip. J. Res. Bus. 2011, 1, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, A.; Kuehn, R. The impact of servicescape on quality perception. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, J.D.; Labagh, R. A strategy for customer satisfaction. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 1992, 33, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadotte, E.R.; Turgeon, N. Key factors in guest satisfaction. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 1988, 28, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, B.J. Frequent travelers: Making them happy and bringing them back. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 1988, 29, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. The effect of the servicescape on customers’ behavioral intentions in leisure service settings. J. Serv. Mark. 1996, 10, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N.T.; Su, Y.L.; Sann, R.; Thanh, L.T.P. Analysis of Online Customer Complaint Behavior in Vietnam’s Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, C. Studying hospitality: Insights from social sciences. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; O’Cass, A. Service branding: Consumer verdicts on service brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2005, 12, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasivyam, K.; Lin, I. The Servicescape. In The Handbook of Hospitality Operation and IT; Jones, P.E., Ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Barich, H.; Kotler, P. A framework for marketing image management. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, S.H. Nurturing corporate images. Eur. J. Mark. 1977, 11, 119–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. The collective impact of service workers and servicescape on the corporate image formation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Countryman, C.C.; Jang, S. The effects of atmospheric elements on customer impression: The case of hotel lobbies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durna, U.; Dedeoglu, B.B.; Balikçioglu, S. The role of servicescape and image perceptions of customers on behavioral intentions in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1728–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hardin, A. The impact of virtual worlds on word-of-mouth: Improving social networking and servicescape in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükergin, K.G.; Dedeoğlu, B.B. The importance of employee hospitability and perceived price in the hotel industry. Anatolia 2014, 25, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Moon, Y.J. Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, M. Managing the Customer Experience: A Measurement-Based Approach; Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, I.A. Exploring customer equity and the role of service experience in the casino service encounter. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areni, C.S.; Kim, D. The influence of in-store lighting on consumers’ examination of merchandise in a wine store. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1994, 11, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellizzi, J.A.; Hite, R.E. Environmental color, consumer feelings, and purchase likelihood. Psychol. Mark. 1992, 9, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, E.R.; Crowley, A.E.; Henderson, P.W. Improving the store environment: Do olfactory cues affect evaluations and behaviors? J. Mark. 1996, 60, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalch, R.F.; Spangenberg, E.R. The effects of music in a retail setting on real and perceived shopping times. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring and Managing Brand Equity, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Safeer, A.A.; He, Y.; Lin, Y.; Abrar, M.; Nawaz, Z. Impact of perceived brand authenticity on consumer behavior: An evidence from generation Y in Asian perspective. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loučanová, E.; Šupín, M.; Čorejová, T.; Repková-Štofková, K.; Šupínová, M.; Štofková, Z.; Olšiaková, M. Sustainability and branding: An integrated perspective of eco-innovation and brand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Kim, D.; Han, S.; Huang, Y.; Kim, J. How does service environment enhance consumer loyalty in the sport fitness industry? The role of servicescape, consumption motivation, emotional and flow experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ryu, K. The roles of the physical environment, price perception, and customer satisfaction in determining customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashikala, R.; Suresh, A. Building consumer loyalty through servicescape in shopping malls. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 10, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Küçükergin, K.G.; Balıkçıoğlu, S. Understanding the relationships of servicescape, value, image, pleasure, and behavioral intentions among hotel customers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, S42–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Siu, N.Y.M. Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J.; Schmitt, B.; Zarantonello, L. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behaviour. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing assets and skills: The key to a sustainable competitive advantage. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1989, 31, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, R., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Baker, T.L. Investigating the role of the physical environment in hedonic service consumption: An exploratory study of sporting events. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P.; Falcão e Cunha, J.; Constantine, L. Multilevel service design: From customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, N.Y.M.; Wan, P.Y.K.; Dong, P. The impact of the servicescape on the desire to stay in convention and exhibition centers: The case of Macao. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.Y. Evaluating a servicescape: The effect of cognition and emotion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 23, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction processes in retail settings. J. Retail. 1981, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gavilanes, J.E.; Ludeña, C.F.; Cassagne, Y.J. Environmental practices in luxury class and first class hotels of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Rosa Dos Ventos 2019, 11, 400–416. [Google Scholar]

- Friske, W.; Cockrell, S.; King, R.A. Beliefs to behaviors: How religiosity alters perceptions of CSR initiatives and retail selection. J. Macromark. 2022, 42, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, N. What is this thing called service? Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 958–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Horng, S.C. Conceptualizing and measuring experience quality: The customer’s perspective. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 2401–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Temizkan, S.P.; Timothy, D.J.; Fyall, A. Tourist shopping experiences and satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.A.; Berry, L.L. The combined effects of the physical environment and employee behavior on customer perception of restaurant service quality. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2007, 48, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, R.J. Organizing for customer service. In Customer Service Delivery: Research and Best Practices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 22–51. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, L.A.; Johnson, S.L. Experience required: Managing each customer’s experience might just be the most important ingredient in building customer loyalty. Mark. Manag. 2007, 16, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, C.C.; Chang, J.H. Mechanism of customer value in restaurant consumption: Employee hospitality and entertainment cues as boundary conditions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.L. The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L.D. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Scholer, A. Engaging the consumer: The science and art of the value creation process. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Back, K.J. Influence of brand relationship on customer attitude toward integrated resort brands: A cognitive, affective, and conative perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B.A.; Wang, Y. The influence of customer brand identification on hotel brand evaluation and loyalty development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Strategy; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. The value of brand equity. J. Bus. Strategy 1992, 13, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, D.; Szmigin, I. Customer perspectives on the role and importance of branding in Irish retail financial services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2005, 23, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z.; Fatma, M. The role of customer brand engagement and brand experience in online banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Morgan, R.M. Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2012, 20, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. Brand experience anatomy in retailing: An interpretive structural modeling approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.; Crane, F.G. Building the service brand by creating and managing an emotional brand experience. J. Brand Manag. 2007, 14, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travelmag. Du Lịch Việt Nam Tăng Trưởng “Thần Kỳ” trong năm 2019 [Vietnam’s Tourism Grew “Miraculously” in 2019]. Analysis Newsletter of Travelmag, 19 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- VNAT. International Visitors (2015–2021). 2021. Available online: https://vietnamtourism.gov.vn/english/index.php/statistic/international (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Vietnam National Administration of Tourism. Vietnam Tourism Annual Report 2019; Vietnam National Administration of Tourism: Hanoi City, Vietnam, 2020.

- EVBN. The Hospitality Market in Vietnam. 2022. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/hotel-market-in-vietnam-to-grow-by-usd-2-12-billion--growing-affordability-and-rising-disposable-income-to-boost-market-growth--17-000-technavio-research-reports-301476429.html (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Tuan, L.T. Driving employees to serve customers beyond their roles in the Vietnamese hospitality industry: The roles of paternalistic leadership and discretionary HR practices. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, G. Vietnam Hotel Upscale Lodging 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.grantthornton.com.vn/globalassets/1.-member-firms/vietnam/media/hotel-survey-2018-executive-summary_eng.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- EVBN. Vietnam Hospitality Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.ccifv.org/le-vietnam/n/news/vietnam-hospitality-report-evbn.html (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Cervellon, M.C.; Galipienzo, D. Facebook pages content, does it really matter? Consumers’ responses to luxury hotel posts with emotional and informational content. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, N.J.; Carlson, J. Examining the drivers and brand performance implications of customer engagement with brands in the social media environment. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilke, O. On the contingent value of dynamic capabilities for competitive advantage: The nonlinear moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Somers, T.M.; Bhattacherjee, A. The role of ERP implementation in enabling digital options: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2009, 13, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.; Bearden, W.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, W. Scale development and construct validity of organizational capital in customer relationship management context: A confirmatory factor analysis approach. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2019, 7, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Faraj, R. Cross-Cultural Aspects of Tourism and Hospitality: A Services Marketing and Management Perspective: By Erdogan Koc; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; 370p, ISBN 978-0-367-862893. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, S.; Patwayati, P. Impact of customer experience and customer engagement on satisfaction and loyalty: A case study in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 983–992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, M.; Poggesi, S. Servicescape cues and customer behavior: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombs, A.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. Social-servicescape conceptual model. Mark. Theory 2003, 3, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. Customer response to intangible and tangible service factors. Psychol. Mark. 1999, 16, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B. How brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment affect loyalty: A reexamination and reconciliation. Ital. J. Mark. 2022, 2, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obilo, O.O.; Chefor, E.; Saleh, A. Revisiting the consumer brand engagement concept. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; O’Cass, A. Examining service experiences and post-consumption evaluations. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.R.; Mullen, M. The servicescape as an antecedent to service quality and behavioral intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, R.; Martinez, E.; Pina, J.M. Effects of service experience on customer responses to a hotel chain. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Xie, L.; Shen, W.G.; Huan, T.C. Are you a tech-savvy person? Exploring factors influencing customers using self-service technology. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yao, Y.; Chang, Y.C. Research on customer behavioral intention of hot spring resorts based on SOR model: The multiple mediation effects of service climate and employee engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, T. Marketing intangible products and product intangibles. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 1981, 22, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A.; Pyun, K. How do customers respond to the hotel servicescape? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnet, D.; Paulsen, N. Service climate, employee identification, and customer outcomes in hotel property rebrandings. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2006, 13, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. The importance of servicescapes in leisure service settings. J. Serv. Mark. 1994, 8, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Agut, S.; Peiró, J.M. Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Huan, T.C. The effects of empowering leadership on employee adaptiveness in luxury hotel services: Evidence from a mixed-methods research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.N.; Hu, C. Investigating the impacts of hotel brand experience on brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand positioning. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. Development of a scale to measure hotel brand experiences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Khan, M.S.; Safeer, A.A. Firm innovation activities and consumer brand loyalty: A path to business sustainability in Asia. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 942048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyama, J.; Nurittamont, W.; Siripipatthanakul, S. Hotel service quality and its effect on customer loyalty: The case of Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Manag. Bus. Healthc. Educ. 2022, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B.; Yu, J.; Han, H. The role of loyalty programs in boosting hotel guest loyalty: Impact of switching barriers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Category | Frequency | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 240 | 61.5 |

| Male | 150 | 38.5 | |

| Age | Under 25 | 55 | 14.1 |

| 25–45 | 243 | 62.3 | |

| Above 45 | 92 | 23.6 | |

| Annual household income | Under USD 1000 | 55 | 14.1 |

| USD 1000–5000 | 60 | 15.4 | |

| USD 5001–10,000 | 112 | 28.7 | |

| USD 10,001–50,000 | 130 | 33.3 | |

| Above USD 50,000 | 33 | 8.5 | |

| Travel frequency | Less than 3 times | 181 | 46.4 |

| 3–5 times | 157 | 40.3 | |

| More than 5 times | 52 | 13.3 | |

| Per night in hotel budget | Under USD 100 | 164 | 42.1 |

| USD 100–200 | 166 | 42.6 | |

| Above USD 200 | 60 | 15.4 | |

| Hotel brand type | Local brand | 262 | 67.2 |

| Foreign brand | 128 | 32.8 | |

| Hotel rating | Four-star hotel | 139 | 35.6 |

| Five-star hotel | 251 | 64.4 | |

| Travel purpose | Business trip | 91 | 23.3 |

| Leisure trip | 299 | 76.7 |

| Variables | α | CR | AVE | MSV | IR | SS | ES | BE | BR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | 0.905 | 0.894 | 0.738 | 0.475 | 0.859 | ||||

| SS | 0.880 | 0.874 | 0.635 | 0.575 | 0.689 ** | 0.797 | |||

| ES | 0.872 | 0.869 | 0.688 | 0.575 | 0.620 ** | 0.758 ** | 0.830 | ||

| BE | 0.952 | 0.925 | 0.757 | 0.198 | 0.445 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.870 | |

| BR | 0.728 | 0.722 | 0.566 | 0.263 | 0.513 ** | 0.203 ** | 0.304 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.752 |

| Variables | Hypotheses | BE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Results | ||

| Independent variables | ||||

| IR | - | 0.34 *** | 0.31 *** | - |

| BR | - | 0.21 *** | 0.19 *** | - |

| Moderate variables | ||||

| IR × BL | H7 | - | 0.39 *** | Supported |

| BR × BL | H8 | - | 0.09 ** | Supported |

| Control variable | ||||

| BL | - | - | 0.30 *** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsou, H.-T.; Hou, C.-C.; Chen, J.-S.; Ngo, M.-C. Rethinking Sustainability Hotel Branding: The Pathways from Hotel Services to Brand Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610138

Tsou H-T, Hou C-C, Chen J-S, Ngo M-C. Rethinking Sustainability Hotel Branding: The Pathways from Hotel Services to Brand Engagement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610138

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsou, Hung-Tai, Chieh-Chih Hou, Ja-Shen Chen, and Minh-Chau Ngo. 2022. "Rethinking Sustainability Hotel Branding: The Pathways from Hotel Services to Brand Engagement" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610138

APA StyleTsou, H.-T., Hou, C.-C., Chen, J.-S., & Ngo, M.-C. (2022). Rethinking Sustainability Hotel Branding: The Pathways from Hotel Services to Brand Engagement. Sustainability, 14(16), 10138. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610138