The Impact of Corporate Culture on Corporate Social Responsibility: Role of Reputation and Corporate Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Review

2.2. Empirical Review

2.2.1. Organizational Culture and CSR

2.2.2. CSR Practices and Reputation

2.2.3. CSR, Reputation, and Corporate Sustainability

2.2.4. Conceptual Framework

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample Procedure

3.2. Research Questionnaire

3.3. Data Analysis and Interpretation

3.4. Common Method Bias

4. Measurement Model

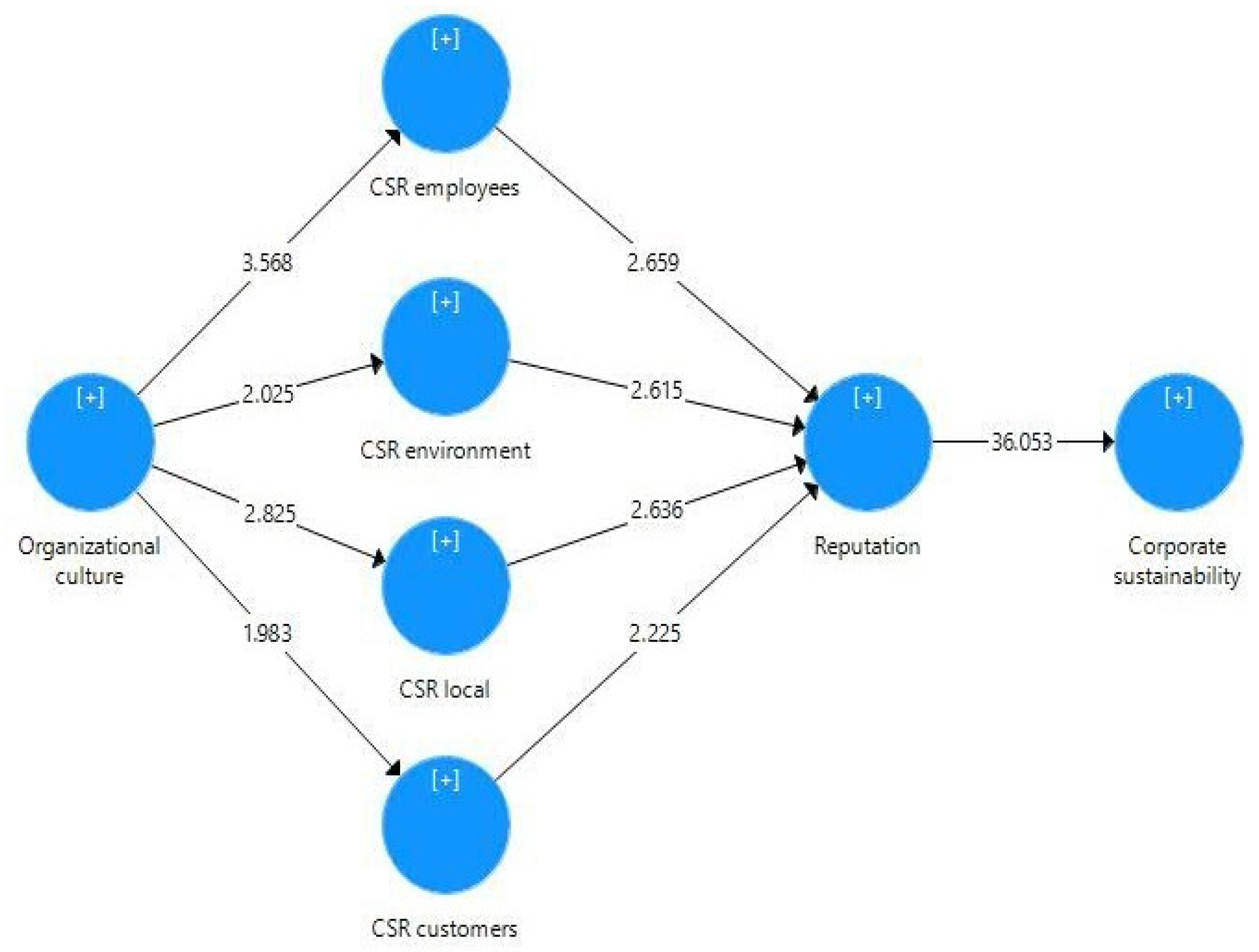

5. Structural Model

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, Q.; Ren, J.; Ren, H.; Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Gu, G.; Guo, K.; Li, J. Urinary Mitochondrial DNA Identifies Renal Dysfunction and Mitochondrial Damage in Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R. Market Orientation and Organizational Performance Linkage in Chinese Hotels: The Mediating Roles of Corporate Social Responsibility and Customer Satisfaction. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 19, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Saeed, M.; Pahi, M.H.; Solangi, R.; Xin, C. They can’t treat you well under abusive supervision: Investigating the impact of job satisfaction and extrinsic motivation on healthcare employees. Ration. Soc. 2021, 33, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuškej, U.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K. The role of consumer–brand identification in building brand relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhang, S.; Du, Q.; Ding, J.; Luan, G.; Xie, Z. Assessment of the sustainable development of rural minority settlements based on multidimensional data and geographical detector method: A case study in Dehong, China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 78, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, A.F.Z.; Hashim, H.A.; Ariff, A.M. Ethical Commitments and Financial Performance: Evidence from Publiciy Listed Companies in Malaysia. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 22, 53–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Briscoe, F.; Hambrick, D.C. Red, blue, and purple firms: Organizational political ideology and corporate social responsibility. Strat. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 1018–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, V.; Jamali, D.; Spence, L.J. Small Business Social Responsibility: A Critical Multilevel Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 934–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrault Sirsly, C.-A.; Lvina, E. From Doing Good to Looking Even Better: The Dynamics of CSR and Reputation. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 1234–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries as an Emerging Field of Study. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 20, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simintiras, A.C.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kaushik, G.; Rana, N.P. Should consumers request cost transparency? Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1961–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, J.L.; Smith, S. Hotel general managers’ perceptions of CSR culture: A research note. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 17, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulidis, B.; Diaz, D.; Crotto, F.; Rancati, E. Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Martín-Samper, R.C.; Köseoglu, M.A.; Okumus, F. Hotels’ corporate social responsibility practices, organizational culture, firm reputation, and performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2014, 27, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Hua, N.; Lee, S. Does size matter? Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Cantallops, A.; Peña-Miranda, D.D.; Ramón-Cardona, J.; Martorell-Cunill, O. Progress in Research on CSR and the Hotel Industry (2006–2015). Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 59, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadh, A.M.; Alyahya, M.S. Impact of organizational culture on employee performance. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, P.J.; Moore, L.F.; Louis, M.R.E.; Lundberg, C.C.; Martin, J.E. Organizational Culture; Sage Publications, Inc.: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. A Study of Corporate Reputation’s Influence on Customer Loyalty Based on PLS-SEM Model. Int. Bus. Res. 2009, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Jiménez-Caballero, J.L.; Martín-Samper, R.C.; Köseoglu, M.A.; Okumus, F. Revisiting the link between business strategy and performance: Evidence from hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.-Y.; Leung, A.S.M. Corporate social responsibility, firm reputation, and firm performance: The role of ethical leadership. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2013, 31, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-B.; Kim, D.-Y. The influence of corporate social responsibility, ability, reputation, and transparency on hotel customer loyalty in the US: A gender-based approach. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J.; Gaikar, V.; Paul, R.; Pech, R. Corporate Culture and Its Impact on Employees’ Attitude, Performance, Productivity, and Behavior: An Investigative Analysis from Selected Organizations of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Corporate Culture and Performance; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maelah, R.; Yadzid, N.H.N. Budgetary control, corporate culture and performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia. Int. J. Glob. Small Bus. 2018, 10, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.L.; Guidry, R.P.; Patten, D.M. Sustainability reporting and perceptions of corporate reputation: An analysis using fortune. Sustain. Environ. Perform. Discl. 2009, 4, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G.; Masiero, L.; Pencarelli, T. Corporate social responsibility and performances of firms operating in the tourism and hospitality industry. TQM J. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osisioma, H.; Nzewi, H.; Paul, N. Corporate social responsibility and performance of selected firms in Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo, M.A.L.; Johannsdottir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzert, N. The impact of corporate reputation and reputation damaging events on financial performance: Empirical evidence from the literature. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.G.; Chen, Z.W.; Ma, G.X. Corporate Reputation and Performance: A Legitimacy Perspective. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, V.; Trez, G. Corporate reputation: A discussion on construct definition and measurement and its relation to performance. Rev. Gestão 2018, 25, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefano, F.; Bagdadli, S.; Camuffo, A. The HR role in corporate social responsibility and sustainability: A boundary-shifting literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 57, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangi, F.; Daniele, L.M.; Varrone, N. How do corporate environmental policy and corporate reputation affect risk-adjusted financial performance? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1975–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Hockerts, K. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Scandinavia: An Overview. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, M.S.; Durrani, L.; Khan, A. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Pakistan: A Critique of the Literature and Future Research Agenda. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2017, 9, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Khattak, A.; Kraslawski, A. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Priorities in the Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) of the Industrial Sector of Sialkot, Pakistan Corporate Social Responsibility in the Manufacturing and Services Sectors; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Lockhart, J.C.; Bathurst, R.J. Institutional impacts on corporate social responsibility: A comparative analysis of New Zealand and Pakistan. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2018, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, E.J.; Ali, A.; Khan, I. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Pakistan. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 16, 786–797. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Khan, N.; Safiullah, A.S.; Baloch, M.S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance of the Firms Listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. Multicult. Educ. 2021, 7, 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedi, K.; Khan, Y.; Lentner, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: Evidence from Pakistani Listed Banks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.; Afshari, L. CSR and employee well-being in hospitality industry: A mediation model of job satisfaction and affective commitment. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Heo, Y.-J.; Nazir, G.; Park, S.-J. Solvent-free, one-pot synthesis of nitrogen-tailored alkali-activated microporous carbons with an efficient CO2 adsorption. Carbon 2021, 172, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ali, G.; Asad, H. Environmental CSR and pro-environmental behaviors to reduce environmental dilapidation: The moderating role of empathy. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Lee, S.; Yoo, C. The effect of national culture on corporate social responsibility in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1728–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K.F.; Pérez, A.; Sahibzada, U.F. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer loyalty in the hotel industry: A cross-country study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Naveed, R.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Adnan, M.; Han, H. Towards the Development of Sustainable Tourism in Pakistan: A Study of the Role of Tour Operators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ásványi, K.; Zsóka, Á. Directing CSR and Corporate Sustainability Towards the Most Pressing Issues. Glob. Chall. CSR Sustain. Dev. 2021, 3, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. Why social responsibility produces more resilient organizations. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2020, 62, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, J.; Lian, Q.; Lv, G.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.-C.T. Recurrently deregulated lncRNAs in hepato-cellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Youth Opportunities Initiative; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.; Grayson, D. World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). In Corporate Responsibility Coalitions; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 300–317. [Google Scholar]

- Horng, J.-S.; Hsu, H.; Tsai, C.-Y. An assessment model of corporate social responsibility practice in the tourism industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1085–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Papania, L. The missing link between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Stakeholder salience and identification. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, R.; Le Bas, C.; Mothe, C.; Poussing, N. Are firms with different CSR profiles equally innovative? Empirical analysis with survey data. Eur. Manag. J. 2013, 31, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S. Stakeholder Theory Classification: A Theoretical and Empirical Evaluation of Definitions. J. Bus. Ethic. 2015, 142, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Nikolakis, W.; Peters, M.; Zanon, J. Trade-offs between dimensions of sustainability: Exploratory evidence from family firms in rural tourism regions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, L.; Fairbrass, J. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Models and Theories in Stakeholder Dialogue. J. Bus. Ethic. 2008, 83, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Song, L.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J.; Luan, G.; Chu, C.; Xie, Z. Night-Time Light Remote Sensing Mapping: Construction and Analysis of Ethnic Minority Development Index. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Activating tourists’ citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of CSR and frontline employees’ citizenship behavior for the environment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1178–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Li, G. The corporate philanthropy and legitimacy strategy of tourism firms: A community perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; Gibson-Sweet, M. The use of corporate social disclosures in the management of reputation and legitimacy: A cross sectoral analysis of UK Top 100 Companies. Bus. Ethic. A Eur. Rev. 1999, 8, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmie, C.R.; Lehnert, K.; Zhao, H. Formal and informal institutional pressures on corporate social responsibility: A cross-country analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalami, W.K.O.A.; Al-Zaman, Q. Role of media and public relations departments in effective tourism marketing in Sharjah. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2021, 5, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.; Mannion, R.; Davies, H.T.; Harrison, S.; Konteh, F.; Walshe, K. The relationship between organizational culture and performance in acute hospitals. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 76, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarba, S.Y.; Ahammad, M.F.; Junni, P.; Stokes, P.; Morag, O. The Impact of Organizational Culture Differences, Synergy Potential, and Autonomy Granted to the Acquired High-Tech Firms on the M&A Performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2017, 44, 483–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Hong, N.; Ryu, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S. Soft robot review. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 2017, 15, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientara, P.; Zamojska, A. Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behaviour in the hotel industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, Y. Corporate Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Soc. Econ. Anal. 2016, 1, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Famiyeh, S.; Kwarteng, A.; Dadzie, S.A. Corporate social responsibility and reputation: Some empirical perspectives. J. Glob. Responsib. 2016, 7, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Jermier, J.M.; Lafferty, B.A. Corporate Reputation: The Definitional Landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.C. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J. A world of reputation research, analysis and thinking—Building corporate reputation through CSR initiatives: Evolving standards. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2005, 8, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.-S.; Lee, M. Doing Right Leads to Doing Well: When the Type of CSR and Reputation Interact to Affect Consumer Evaluations of the Firm. J. Bus. Ethic. 2011, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosmanoglu, E.; Altinigne, N.; Isiksal, D.G. CSR motivation and customer extra-role behavior: Moderation of ethical corporate identity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4161–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G.; Lui, T.-W.; Grün, B. The impact of IT-enabled customer service systems on service personalization, customer service perceptions, and hotel performance. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, S. Revisiting the financial performance—Corporate social performance link. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2586–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukusta, D.; Mak, A.; Chan, X. Corporate social responsibility practices in four and five-star hotels: Perspectives from Hong Kong visitors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, H.; Huang, S.S. Does conspicuous decoration style influence customer’s intention to purchase? The moderating effect of CSR practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nysveen, H.; Oklevik, O.; Pedersen, P.E. Brand satisfaction: Exploring the role of innovativeness, green image and experience in the hotel sector. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2908–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fai, L.Y.; Song, H.J.; Kang, K.H. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Brand Image in the Malaysian Hotel Industry: The Moderating Role of Brand Origin. J. Korea Serv. Manag. Soc. 2017, 18, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-S.; Chiang, C.-F.; Huangthanapan, K.; Downing, S. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability balanced scorecard: The case study of family-owned hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 48, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Tarí, J.J.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. The effects of quality and environmental management on competitive advantage: A mixed methods study in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Trujillo, A.M.; Velez-Ocampo, J.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A. A literature review on the causality between sustainability and corporate reputation: What goes first? Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H. Linking stakeholders and corporate reputation towards corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Othman, S.; Othman, R. Islamic corporate social responsibility, corporate reputation and performance. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2012, 6, 643–647. [Google Scholar]

- Esen, E. The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Activities on Building Corporate Reputation International Business, Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S.; Bryman, A.; Ferguson, H. Understanding Research for Social Policy and Social Work 2E: Themes, Methods and Approaches; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kauff, N.D.; Satagopan, J.M.; Robson, M.E.; Scheuer, L.; Hensley, M.; Hudis, C.A.; Ellis, N.A.; Boyd, J.; Borgen, P.I.; Barakat, R.R.; et al. Risk-Reducing Salpingo-Oophorectomy in Women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2002, 57, 574–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, A.; Litzelman, K.; Wisk, L.E.; Maddox, T.; Cheng, E.R.; Creswell, P.D.; Witt, W.P. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Shi, F.; Okumus, F. Exploring the links among corporate social responsibility, reputation, and performance from a multi-dimensional perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Method for Business: A Skill Development Approach, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, P.S.; Lemeshow, S. Sampling of Populations: Methods and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highhouse, S. Designing Experiments That Generalize. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 12, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rada, V.D. Ventajas e inconvenientes de la encuesta por Internet. Rev. Sociol. 2012, 8, 193–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugenda, O.M.; Mugenda, A.G. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Research Methods Africa Center for Technology Studies (Acts) Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethic. 2008, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, H. Exploring the Organizational Culture’s Moderating Role of Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Firm Performance: Focused on Corporate Contributions in Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, D.B. Organizational culture and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2003, 18, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C.; Moutinho, L. Brand relationships through brand reputation and brand tribalism. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publication Inc.: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Siyal, S.; Xin, C.; Peng, X.; Siyal, A.W.; Ahmed, W. Why do highperformance human resource practices matter for employee outcomes in public sector universities? The mediating role of person–organization fit mechanism. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020947424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Xin, C.; Umrani, W.A.; Fatima, S.; Pal, D. How do leaders influence innovation and creativity in employees? The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Adm. Soc. 2021, 53, 1337–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Peng, X. Does leadership lessen turnover? The moderated mediation effect of leader–member exchange and perspective taking on public servants. J. Public Aff. 2018, 18, e1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. PLS-Graph user’s guide. In CT Bauer College of Business; University of Houston: Houston, TX, USA, 2001; Volume 15, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Fassott, G. Testing moderating effects in PLS path models: An illustration of available procedures. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 713–735. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, D.J.; Knott, M.; Moustaki, I. Latent Variable Models and Factor Analysis: A Unified Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 904. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, M.C.; Becker, J.M.; Wende, S. SmartPLS 3; Smart PLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publication Inc.: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. Bridging Design and Behavioral Research with Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.T.; Campbell, D.E.; Thatcher, J.B.; Roberts, N. Operationalizing multidimensional constructs in structural equation modeling: Recommendations for IS research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 30, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Rai, A.; Rigdon, E. Predictive validity and formative measurement in structural equation modeling: Embracing practical relevance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS) 2013, Milano, Italy, 15–18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schlittgen, R.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Becker, J.-M. Segmentation of PLS path models by iterative reweighted regressions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4583–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H. Testing the claims of new urbanism: Local access, pedestrian travel, and neighboring behaviors. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, S.; Straub, D.; Rai, A. Specifying Formative Constructs in Information Systems Research. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative Versus Reflective Indicators in Organizational Measure Development: A Comparison and Empirical Illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogobete, D. Negotiating Desire in Joyce carol Oates’sa Fair Maiden. BAS Br. Am. Stud. 2013, 19, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, S.A.; Othman, A.R.; Perumal, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Company Performance in the Malaysian Context. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 65, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Zain, M.M.; Sulaiman, M.; Sarker, T.; Ooi, S.K. Empowering society for better corporate social responsibility (CSR): The case of Malaysia. Kaji. Malays. 2013, 31, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Nyahunzvi, D.K. CSR reporting among Zimbabwe’s hotel groups: A content analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Guix, M.; Bonilla-Priego, M.J. Corporate social responsibility in cruising: Using materiality analysis to create shared value. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Walmsley, A.; Cogotti, S.; McCombes, L.; Häusler, N. Corporate social responsibility: The disclosure–performance gap. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A.; Farmakis, P. A stakeholder approach to CSR in hotels. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P. Corporate Social Responsibility in Hospitality: Issues and Implications. A Case Study of Scandic. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahap, J.; Ramli, N.S.; Said, N.M.; Radzi, S.M.; Zain, R.A. A study of brand image towards customer’s satisfaction in the Malaysian hotel industry. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 149–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Velasco, C.A.; Quintana-García, C.; Marchante-Lara, M. Total quality management, corporate social responsibility and performance in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdoun, M.; Zouaoui, M. Impact of environmental management on competitive advantage of Tunisian companies: The mediator role of organizational culture. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2017, 7, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Banfi, F.; Fai, S.; Brumana, R. BIM automation: Advanced modeling generative process for complex structures. In Proceedings of the 26th International CIPA Symposium on Digital Workflows for Heritage Conservation, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 28 August–1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez García de Leaniz, P.; Herrero Crespo, Á.; Gómez López, R. Respuestas de los consumidores a los hoteles certificados medioambientalmente: El efecto moderador de la conciencia medioambiental sobre la formación de intenciones comportamentales. In Proceedings of the XXIX Congreso de Marketing AEMARK, Seville, Spain, 6–8 September 2017; pp. 1072–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, P.J.; Allen, J.E.; Biswas, S.K.; Fisher, E.A.; Gilroy, D.W.; Goerdt, S.; Gordon, S.; Hamilton, J.A.; Ivashkiv, L.B.; Lawrence, T.; et al. Macrophage Activation and Polarization: Nomenclature and Experimental Guidelines. Immunity 2014, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Blumberg, I. The power (lessness) of industry self-regulation to promote responsible labor standards: Insights from the Chinese toy industry. J. Bus. Ethic. 2017, 143, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, I.; Kiessling, T.; Harvey, M. Corporate social responsibility: Why bother? Organ. Dyn. 2014, 43, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Hustvedt, G. Building trust between consumers and corporations: The role of consumer perceptions of transparency and social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønn, P.S.; Vidaver-Cohen, D. Corporate Motives for Social Initiative: Legitimacy, Sustainability, or the Bottom Line? J. Bus. Ethic. 2008, 87, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainaghi, R.; Phillips, P.; Baggio, R.; Mauri, A. Cross-citation and authorship analysis of hotel performance studies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Acceptability |

|---|---|

| Harman’s Single Factor Test | 31.472% variance proportion |

| VIF < 5 | DT |

|---|---|

| Organizational culture | 2.998 |

| Reputation | 2.182 |

| CSR toward employees | 1.877 |

| CSR toward customers | 2.894 |

| CSR toward environment | 2.674 |

| CSR toward local community | 2.032 |

| R Square | R Square Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate reputation | 0.839 | 0.836 |

| DT | |

|---|---|

| Organizational culture | 0.345 |

| Reputation | 0.161 |

| CSR toward employees | 0.224 |

| CSR toward customers | 0.225 |

| CSR toward the environment | 0.355 |

| CSR toward local community | 0.173 |

| Construct | Items | Weights | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhocracy culture | AC1 | 0.856 | 0.749 | 0.857 | 0.666 | |

| AC2 | 0.775 | |||||

| AC3 | 0.816 | |||||

| Clan culture | CC1 | 0.824 | 0.749 | 0.857 | 0.666 | |

| CC2 | 0.818 | |||||

| CC3 | 0.806 | |||||

| Hierarchy culture | HC1 | 0.75 | 0.701 | 0.823 | 0.609 | |

| HC2 | 0.85 | |||||

| HC3 | 0.737 | |||||

| Market culture | MC1 | 0.783 | 0.746 | 0.856 | 0.664 | |

| MC2 | 0.810 | |||||

| MC3 | 0.715 | |||||

| CSR customers | CSR_Cus1 | 0.729 | 0.702 | 0.820 | 0.606 | |

| CSR_Cus2 | 0.897 | |||||

| CSR_Cus3 | 0.705 | |||||

| CSR employees | CSR_Emp1 | 0.739 | 0.814 | 0.868 | 0.569 | |

| CSR_Emp2 | 0.775 | |||||

| CSR_Emp3 | 0.722 | |||||

| CSR_Emp4 | 0.741 | |||||

| CSR_Emp5 | 0.792 | |||||

| CSR environment | CSR_Env1 | 0.797 | 0.716 | 0.837 | 0.634 | |

| CSR_Env2 | 0.703 | |||||

| CSR_Env3 | 0.887 | |||||

| CSR local | CSR_Loc1 | 0.741 | 0.795 | 0.857 | 0.603 | |

| CSR_Loc2 | 0.785 | |||||

| CSR_Loc3 | 0.709 | |||||

| CSR_Loc4 | 0.902 | |||||

| Reputation | Rep1 | 0.831 | 0.704 | 0.836 | 0.629 | |

| Rep2 | 0.742 | |||||

| Rep3 | 0.803 | |||||

| Corporate sustainability | CS1 | 0.728 | 0.760 | 0.863 | 0.678 | |

| CS2 | 0.855 | |||||

| CS3 | 0.88 | |||||

| Organizational Culture * | Adhocracy culture | 0.357 | ||||

| Clan culture | 0.348 | |||||

| Hierarchy culture | 0.356 | |||||

| Market culture | 0.382 |

| CSR Customers | CSR Employees | CSR Environment | CSR Local | Corporate Sustainability | Reputation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR customers | 0.798 | |||||

| CSR employees | 0.077 | 0.892 | ||||

| CSR environment | 0.760 | 0.563 | 0.850 | |||

| CSR local | 0.755 | 0.087 | 0.191 | 0.821 | ||

| Corporate sustainability | 0.11 | 0.136 | 0.110 | 0.271 | 0.732 | |

| Reputation | 0.174 | 0.125 | 0.144 | 0.121 | 0.132 | 0.843 |

| CSR Customers | CSR Employees | CSR Environment | CSR Local | Corporate Sustainability | Reputation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR customers | ||||||

| CSR employees | 0.034 | |||||

| CSR environment | 0.671 | 0.314 | ||||

| CSR local | 0.356 | 0.056 | 0.691 | |||

| Corporate sustainability | 0.146 | 0.536 | 0.130 | 0.087 | ||

| Reputation | 0.189 | 0.625 | 0.134 | 0.112 | 0.383 |

| Beta | SD | T Statistics | p Values | 2.50% | 97.50% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR customers ⟶ Reputation | 0.24 | 0.106 | 2.225 | 0.034 | 0.152 | 0.348 |

| CSR employees ⟶ Reputation | 0.297 | 0.061 | 2.659 | 0.019 | 0.107 | 0.401 |

| CSR environment ⟶ Reputation | 0.276 | 0.126 | 2.615 | 0.02 | 0.151 | 0.365 |

| CSR local ⟶ Reputation | 0.283 | 0.129 | 2.636 | 0.019 | 0.109 | 0.376 |

| Organizational culture ⟶ CSR customers | 0.156 | 0.066 | 1.983 | 0.047 | 0.148 | 0.27 |

| Organizational culture ⟶ CSR employees | 0.201 | 0.057 | 3.568 | 0 | 0.117 | 0.305 |

| Organizational culture ⟶ CSR environment | 0.161 | 0.074 | 2.825 | 0.015 | 0.146 | 0.293 |

| Organizational culture ⟶ CSR local | 0.191 | 0.08 | 2.025 | 0.045 | 0.125 | 0.299 |

| Reputation ⟶ Corporate sustainability | 0.818 | 0.023 | 35.211 | 0 | 0.766 | 0.855 |

| CSR customers ⟶ Reputation ⟶ Corporate sustainability | 0.196 | 0.084 | 2.125 | 0.039 | 0.16 | 0.372 |

| CSR employees ⟶ Reputation ⟶ Corporate sustainability | 0.243 | 0.065 | 2.226 | 0.033 | 0.123 | 0.412 |

| CSR environment ⟶ Reputation ⟶ Corporate sustainability | 0.238 | 0.095 | 2.222 | 0.034 | 0.136 | 0.403 |

| CSR local ⟶ Reputation ⟶ Corporate sustainability | 0.232 | 0.098 | 2.011 | 0.046 | 0.141 | 0.391 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siyal, S.; Ahmad, R.; Riaz, S.; Xin, C.; Fangcheng, T. The Impact of Corporate Culture on Corporate Social Responsibility: Role of Reputation and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610105

Siyal S, Ahmad R, Riaz S, Xin C, Fangcheng T. The Impact of Corporate Culture on Corporate Social Responsibility: Role of Reputation and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610105

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiyal, Saeed, Riaz Ahmad, Samina Riaz, Chunlin Xin, and Tang Fangcheng. 2022. "The Impact of Corporate Culture on Corporate Social Responsibility: Role of Reputation and Corporate Sustainability" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610105

APA StyleSiyal, S., Ahmad, R., Riaz, S., Xin, C., & Fangcheng, T. (2022). The Impact of Corporate Culture on Corporate Social Responsibility: Role of Reputation and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability, 14(16), 10105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610105