1. Introduction

For many consumers today, organic food is commonplace. In the European Union (EU), organic food can be obtained from specialist retailers, discounters, and the fast-growing movement of community-supported agriculture (CSA). The organic food market is expanding rapidly. With the growth of organic farming, the demand for suitable organic seed and vegetative propagation material is also growing. A wide range of locally adapted crop species and cultivars is needed to use the potential of organic farming in diverse areas fully. Genetic diversity is key for adaptation to changing environmental conditions. Thus far, much of the seed and vegetative propagation material used in organic farming are grown organically but not bred organically. Thus, they may lack specific traits relevant to organic cultivars.

A shortage of funds for organic plant breeding appears to be the main constraint to increasing organic breeders’ efforts to satisfy the demand for organically bred cultivars. Plant breeders, farmers and other actors in the organic food supply chain are increasingly asking why funding is insufficient and how this problem can be solved. This paper briefly reviews the general development and present state of plant breeding. It then introduces organic plant breeding as a new sub-sector, analyses the shortcomings in financing it, and proposes viable options. This study builds on surveys, interviews and workshops with stakeholders in plant breeding, seed production and the food value chain.

1.1. Plant Breeding in Transition

Our crops are the result of selection over thousands of years, an evolution directed by humans [

1]—both men and women [

2]. Scientific plant breeding emerged only in the second half of the 19th century [

3]. At that time, farmers, for instance, in Germany, were interested in new cultivars that would allow them to make better use of their investments in soil fertility through an improved three-year crop rotation. The first scientific-oriented breeding approaches emerged in many places and over a relatively short period. Soon afterwards, the foundations were laid to regulate the seed market [

4]. Seed quality control centres were established, a procedure for cultivar recognition and protection was developed, and a cultivar registry was put in place. These regulatory processes had an enormous impact on plant breeding and agriculture. With the new cultivars, the yield of many crops was increased. Resistance to diseases that had sometimes led to crop failure was greatly improved. Plant breeding has been the greatest contributor to the intensification of agriculture, clearly ahead of the contribution of mineral fertilisers and chemical plant protection [

5].

The regulation of seed markets triggered a process of privatising seed. Privatisation contributed greatly to the disappearance of economically less important or only locally important crops and cultivars, thus a major loss of agrobiodiversity. Privatisation led to market consolidation of the seed sector [

6]. In the beginning, the farmers—either individually or cooperatively—started to breed and sell improved cultivars. Soon, these entities became specialised plant-breeding companies. A new economic sector of mainly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) developed. In the 1970s, international chemical companies discovered plant breeding as a highly profitable business. This led them to acquire seed companies, setting in motion a process of market concentration [

7]. Today, only three international chemical companies control more than 60% of the global commercial seed market, reaching monopoly-like proportions [

8].

Essentially, the financing of private plant breeding is based on royalties from intellectual property rights (IPRs) such as plant variety protection (PVP) and patents [

9,

10]. In the IPRs-based financing system, cultivars are most profitable when grown on a large scale. Consequently, this business model promotes standardised and uniform agricultural production and contributes to reducing crop diversity. The formation of monopolies also creates growing dependence of seed users and society as a whole on only a few companies. All this has reduced agrobiodiversity tremendously and puts the sustainability of agriculture and food at risk.

There is a mismatch between supply and demand. The conventional seed market offers an impressive number of cultivars for our main crops, but many of them are similar, differing little from one another. Genetic uniformity prevails due to the one-sided focus in breeding on a limited number of traits such as high yield, uniform time of maturity or short straw in cereals [

11]. Furthermore, uniformity is legally required to register and protect a cultivar as being private and exclusive, as demanded by the EU’s Plant Variety Property Rights (CVPR). Therefore, IPRs-based plant breeding is not sufficient to provide the plant genetic diversity that our planet needs. It can be assumed that only a few agricultural crops are subjected to intensive breeding efforts, resulting in fairly homogeneous high-performing cultivars for large-scale distribution.

However, uniformity in crop production is the opposite of what is needed to meet the main challenges in today’s agriculture [

6,

12]. Adapting cropping systems to climate change, generating food security for an expected 11 billion people [

13] and transforming production systems from chemical-based to organic farming are huge tasks in which plant breeding plays a vital role. Rich biodiversity is the basis for the resilience and adaptability of cropping systems [

14]. Diverse crop rotations, the cultivation of many different crops and the use of productive and sufficiently heterogeneous cultivars are the main elements to optimise cropping systems ecologically. It is also necessary to preserve cultural landscapes and their ecosystem services. Therefore, suitable cultivars need to be generated by plant breeding [

15]. However, the private seed sector is structured and financed in a way that will not be sufficient to provide this crucial diversity. Alternatives to complement conventional plant breeding must be further developed.

1.2. Organic Plant Breeding—A Novelty

As an alternative to conventional plant breeding, organic plant breeding has emerged as a novelty in the seed market [

16]. Organic plant breeding is defined mainly by the breeding technologies used [

17]. The genome is respected in a way that physical insertion, deletions or rearrangements of the genome are not allowed, the plant cell is respected as an indivisible functional entity, and methods of genetic engineering are excluded [

18,

19]. Furthermore, a key objective is to sustain and increase agricultural biodiversity. Based on these definitions, a private standard and certification system for organic plant breeding has recently been established.

Organic plant breeding was founded by pioneers mainly from the biodynamic agricultural movement. Most of these breeding initiatives are in Germany, Switzerland, Austria and the Netherlands. Within the past 25 years, the organic sector recorded considerable growth. Still, the development of organic plant breeding and seed production has not kept up with the increase in area under organic crop management—currently about 10% of the total cultivated area in the EU [

20]. Therefore, most cultivars used in organic agriculture are still derived from conventional plant breeders, even if the seed is produced organically. Today, organic plant breeding is an established niche in the seed market. Its contribution to seed supply is still small, and the lack of financial resources is a key constraint to expanding organic breeding [

21,

22]. Available funds have been growing continuously by about 10% per year, and a total volume of 4–5 million Euros was recently estimated for the four countries mentioned above [

23]. But current needs for organic breeding are estimated to be at least 100 million Euros per year [

24].

1.3. Seed as a Commons for an Alternative Economy

For some years now, a renaissance of commoning–social cooperation in the use of commons–can be observed, shaping social discourses and practice. Commons research has been established as a new scientific discipline. Particularly ground-breaking was the work of Elinor Ostrom. In numerous case studies, she and her team investigated how social groups worldwide manage their natural resources–land, forests, pastures, and fishing grounds–collaboratively and as a common good. Ostrom refuted Hardin’s thesis of the “tragedy of the commons” [

25], based on the assumption of inevitable overuse and destruction of a common good by individuals. She provided evidence that an economy based on commons can be very sustainable as long as clear rules have been agreed. In essence, she postulated seven design principles for the successful management of commons [

26]. For this achievement, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

In plant breeding, the concept of the commons is gaining importance: organic plant breeders work in the framework of non-profit organisations that also function as cultivar owners [

27]. The vegetable breeders of the German association Kultursaat e.V. go one step further. They completely forego PVP [

28] and release their new cultivars freely available for everybody–but with no protection against the renewed private appropriation of derivatives such as new populations, breeding lines and cultivars.

There are two key principles in managing commons. Commons need to be protected if they are to be maintained. There can be no commons without commoning: rules and regulations must be made and applied by the people concerned [

29]. The open source principle was developed on this basis. Computer scientists in the 1980s created the software open-source licence, which led to various Creative Commons Licenses for manifold products under copyright law [

30].

With respect to open source seed, there are basically three rules [

31]:

Seed may be used for any purpose and by anyone;

No one may apply IPRs such as patents or PVP to the seed and its derivatives;

All recipients of open source seed transfer the same rights and obligations to future users of the seed and its derivatives. This obligation, referred to as “copyleft,” secures that the seed and all its derivatives through subsequent plant breeding remain open source and thus a commons.

Following these rules, there are two approaches to support breeders and seed producers to manage seed as a commons. The Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) in the USA pursues an ethical approach using a pledge [

32]. OpenSourceSeeds, hosted by Agrecol Association for AgriCulture & Ecology in Germany, and Bioleft in Argentina use open source seed licences that can be legally enforced [

33,

34]. Other initiatives are underway [

35]. Open source seed closes a gap in the current practice of organic plant breeding. Thus far, most new cultivars have been released without any protection, a practice that can be referred to as “open-access” and carries the risk of future appropriation by the private sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Formulating Research Questions

Following a short analysis of the plant breeding sector, three steps were taken to find new economic models for seed as a commons: (i) the constraints to financing organic plant breeding were analysed; (ii) attitudes of stakeholders towards an open source strategy and their willingness to contribute to financing organic plant breeding were assessed, and (iii) new financing concepts were developed.

2.2. Analysing Constraints to the Financing of Organic Plant Breeding

In 2015 and 2016, Agrecol analysed the situation concerning the financing of organic plant breeding and sought solutions to improve the situation. A survey was conducted anonymously among organic cereal and vegetable plant breeders in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Fourteen responded. Their sources of funding and their constraints in acquiring funds for breeding were assessed, and ideas on how to improve the financing of organic plant breeding were gathered. Five breeders representing five plant breeding initiatives and eight other stakeholders in organic seed systems (see acknowledgements) came together in a workshop to review the survey results and jointly analyse the constraints to financing organic plant breeding [

36].

2.3. Exploring Attitudes towards Open Source Seed Systems

In 2017, Agrecol promoted a newly released open source licenced wheat cultivar. Stakeholders along the food value chain included farmers, a miller and several bakers. Since then, Agrecol has collaborated with bakeries that offer “open source bread” and investigated consumer attitudes towards seed as a commons and using an open source strategy. A survey addressing the general public was conducted in 2021 using social media Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and Mastodon and Agrecol’s listserv. Multiple answers were possible. Completed questionnaires were received from 168 respondents. The survey focused on their willingness to contribute to funding and their ability to understand a commons-based approach to plant breeding with an open source strategy [

37].

2.4. Developing Alternatives to Financing Plant Breeding

The development of an open source strategy for seed began in 2015 and included the search for alternatives to financing plant breeding. Agrecol published the Open Source Seed Licence in 2016 and launched the project OpenSourceSeeds in 2017, a service provider [

38] that supports plant breeders and all other stakeholders in the seed value chain to test this strategy. The fact that this strategy excludes revenues from IPRs-based funding directed the focus on finding alternatives for financing plant breeding. Non-proprietary concepts were identified in an interdisciplinary workshop in 2019 by a group of breeders, seed producers and commons experts [

39].

3. Results

3.1. Constraints to Financing Organic Plant Breeding

The survey among organic cereal breeders indicated that royalties from PVP contributed very little or nothing to cover the costs for breeding. The biggest share came from donations and subsidies.

Table 1 provides the figures in detail [

36]. Foundations alone contributed 52% on average. Foundations, together with donations from individuals and government programmes, amount to more than two-thirds of organic plant breeders’ budgets on average. Despite an impressive amount of funds raised every year from foundations, individual donors and government programmes, the financing situation of most organic plant breeders remains tight and insecure, as these financing sources have limited funding capacity and restricted periods. Funding is given for projects of a few years only.

There are several reasons why IPRs-based financing contributes so little. Firstly, the area cropped with organic cultivars is too small to generate sufficient income from royalties. Secondly, the large-scale use of one cultivar contradicts the need for diversity in organic cropping systems. Thirdly, most organic plant breeders consider their cultivars a commons and reject the idea of claiming IPRs. This is also reflected in the standards of Bioverita: “… varieties and their characteristics may not be patented or given exclusive rights, so that they are freely available to every breeder and grower” [

40,

41]. Claiming IPRs and creating plant genetic diversity contradict each other. As the latter is the main goal in organic plant breeding, it can be concluded that alternatives to the IPRs-based financing model are needed.

3.2. The Potential of Consumers

Consumers are key to achieving a successful financing strategy for non-private seed. The great public interest in open source licensing is based on the social perception that the current situation of privatisation and monopoly formation in the seed sector is not sustainable [

42,

43]. In our online survey, a large majority supported an open source seed strategy.

The main results of the consumer survey are summarised in

Table 2. They suggest that “seed as a commons” and “organic” are seen as belonging together. Because of the small number of survey participants, the findings on consumer attitudes can give only a first indication. The results are confirmed by Kliem et al. [

44], who assessed the acceptance of the first open-source tomato Sunviva. In addition, the survey confirmed consumer reactions to Agrecol’s “Open-Source Bread” campaign in Berlin bakeries [

45].

It can be concluded that open source could become a strong buying argument for consumers: it stands for diversity and seed as a commons. It would give crop cultivars and their products additional marketing potential. In addition, the Open Source Seed Licence allows individuals to actively support organic breeding: 92% of the consumers surveyed expressed willingness to pay a premium for food from open source seed.

This positive reaction of consumers suggests that open source for organic seed could become a successful narrative that creates awareness among customers and emphasises the need for organic plant breeding. In this respect, the initiative of OpenSourceSeeds to introduce an open source licence is a useful complement to the value-chain approach as discussed above.

3.3. Alternative Financing Models

The participants of the interdisciplinary workshop in 2019 formulated several innovative ideas for financing organic plant breeding, presented below.

3.3.1. Community-Based Plant Breeding

As illustrated in

Figure 1, community-based plant breeding follows a strategy in which several farms in one natural region (landscape unit) operate and finance plant breeding collectively, aiming to develop locally adapted cultivars. Today, so-called farmers’ varieties or regional cultivars would be a promising way to give value to site-specific characteristics. A higher level of resilience to weather extremes could be reached with a certain degree of heterogeneity of cultivars. Initial results from breeding with organic populations go in this direction [

46].

Community-based plant breeding requires new forms of organisation and financing. Essentially, two forms are conceivable:

Several crop-farming and horticultural businesses operating under similar agroecological conditions join forces in managing a joint breeding programme. Together, they finance a professional plant breeder or give the task to a breeding company.

Associations of CSA groups practise regional plant breeding. With this option, producers and consumers finance the breeding jointly. Several CSA groups may cooperate and share costs among the combined members.

The commissioning parties for plant breeding are either producer communities or producer-consumer communities. For both, the legal entity could be a cooperative. The cooperative could share the costs according to the size of the different member organisations. It is also conceivable to apply the CSA-proven tool of a bidding round for a breeding programme. In this case, the expected costs are made known in advance. All participants then offer the amount they are willing to contribute according to their judgment. The bidding procedure is repeated until sufficient funds are collected to cover the budget. If the difference between the funds offered and the planned budget remains high, the proposed breeding programme can be discussed, reconsidered and further adapted.

Another advantage of community-based plant breeding is that the periods for breeding can be shortened and costs saved. For internal use within the community, cultivars can be used earlier and with less homogeneity and stability than required for official registration. Indeed, official testing and registration could be foregone, saving both time and costs. Suppose an internally used cultivar proves particularly successful and shows potential for seed production and commercial use. In that case, its breeding process could still be completed with respect to meeting the officially required DUS (distinctness, uniformity, stability) criteria, and the cultivar could be officially registered with the authorities.

Next to financing, community-based plant breeding enables cooperation between all stakeholders, similar to the concept of participatory plant breeding. The breeders’ objectives, the farmers’ and gardeners’ expectations, and the consumers’ wishes can be more closely aligned. Supply and demand can be matched more effectively.

Thus far, there is little experience with community-based plant breeding. However, it has the great advantage that this approach to breeding can be started on a small scale, for example, with only one crop, such as developing a locally improved wheat population.

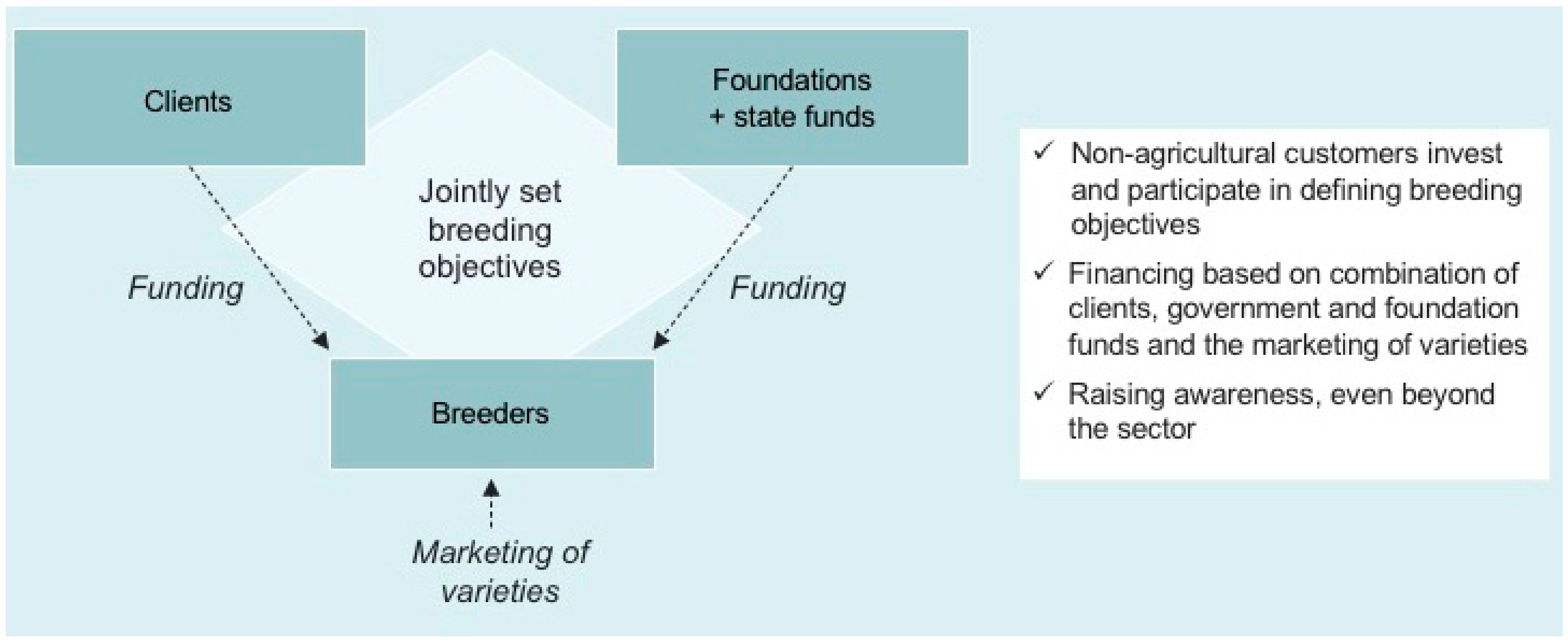

3.3.2. Breeding on Demand

Breeding on demand, as shown in

Figure 2, is oriented towards the ideas and wishes of the clients, who partly or completely cover the costs for breeding. The breeders and clients jointly design the breeding programme and set the breeding objectives.

When plant breeding is offered on demand, new stakeholders can be involved. Anyone who expects this to benefit their company or area of responsibility can be considered a client, for example:

A supermarket that wants to offer special regional products.

A waterworks that depends on organic production for treating its drinking water; promoting organic varieties can help keep pesticide and nitrate levels low in the long term.

A company that wants to make a stronger commitment to sustainability by investing in environmentally friendly projects, for instance, corporate social responsibility.

In Switzerland, a group of companies is moving towards contract research, focusing on sunflowers. Since sunflowers for producing oleic acid to use in cosmetics are currently available only as hybrids, the group commissioned a breeder to develop an open-pollinating cultivar. The group is committed to financing this task over the long term, allowing breeders to plan their budgets better. This is one example of largely untapped potential.

Breeding on demand enables financing of breeding of niche crops in addition to crop cultivars suitable for the market and mass production. Generally, it can help make breeding more oriented to needs and enhance cultivar diversity. In addition, as a service-based approach, it offers great potential for raising awareness about plant breeding beyond the agricultural sector.

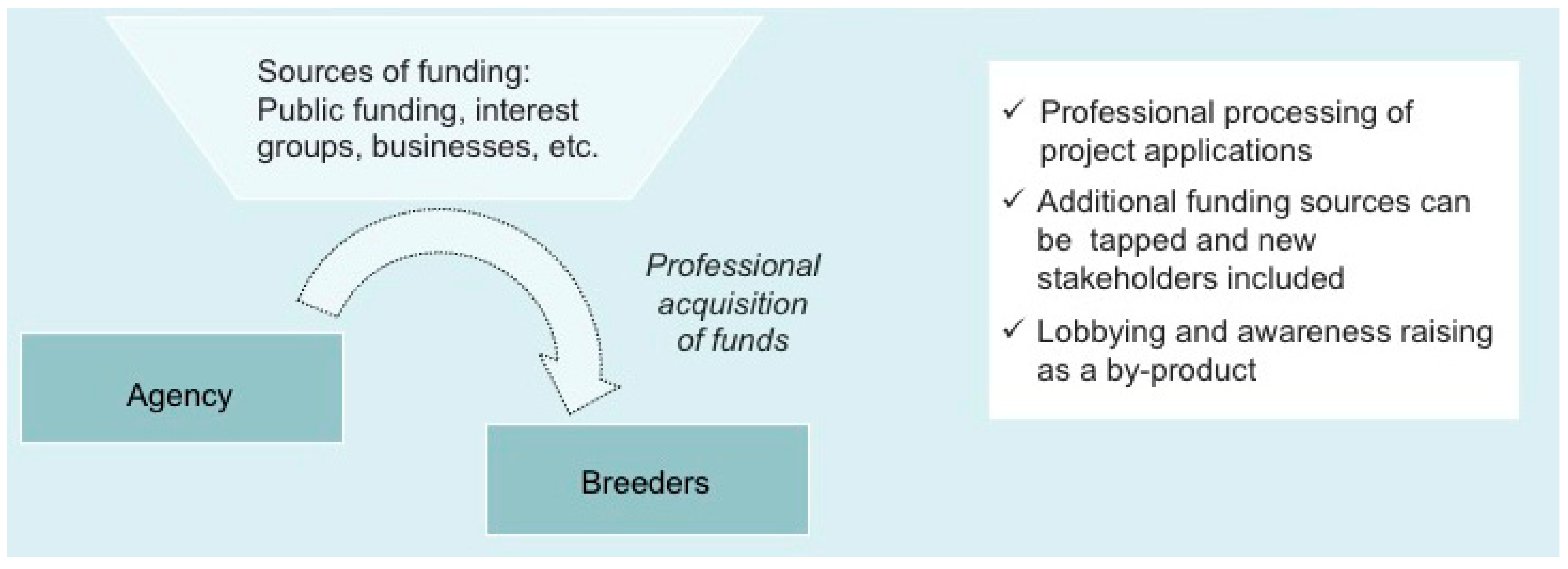

3.3.3. Outsourcing the Acquisition of Funds

Currently, many breeders in the organic sector suffer from the considerable bureaucracy involved in acquiring funds. Much time that would be needed for the actual task of plant breeding is thus lost. This raises the question of whether fundraising and possibly financial management of funded breeding projects could be outsourced and delegated to a specialised service provider (

Figure 3).

An organisation specialised in acquisition and accounting can work more professionally than most breeders can; this would lead to more efficient financing of plant breeding. Moreover, through such an agency, several small and medium-sized breeding projects can be combined into a larger programme, for which funds can be raised jointly. This allows access to new funding sources, as some important sources can be tapped only above a certain level of funding, a level too high for individual breeders with their relatively small breeding programmes. In addition, an agency could involve new stakeholders such as:

Local authorities that are committed to regional development,

Organisations that want to promote biodiversity or

Companies that are committed to environmental protection and strive for a greener image.

Another positive side effect of outsourcing acquisition and financial management should not be underestimated: an agency can represent the interests of breeders and act as a partner for lobbying and awareness raising.

A model between “do it yourself” and outsourcing is practised successfully by Kultursaat e.V. in Germany. Small-scale vegetable breeders formed an association in which they set up a service unit for raising and managing funds. However, these funds are often insufficient for their purposes, and the breeders raise additional money alone.

Completely outsourcing this function may allow more flexibility and openness for cooperation with very different customers and creating breeding programmes with clear profiles but different consortium partners. The latter increases the chances of success in raising funds. Such agencies already exist in other sectors, for instance, Emcra, an agency for acquiring EU funding [

47]. Looking into their experience could bring important insights.

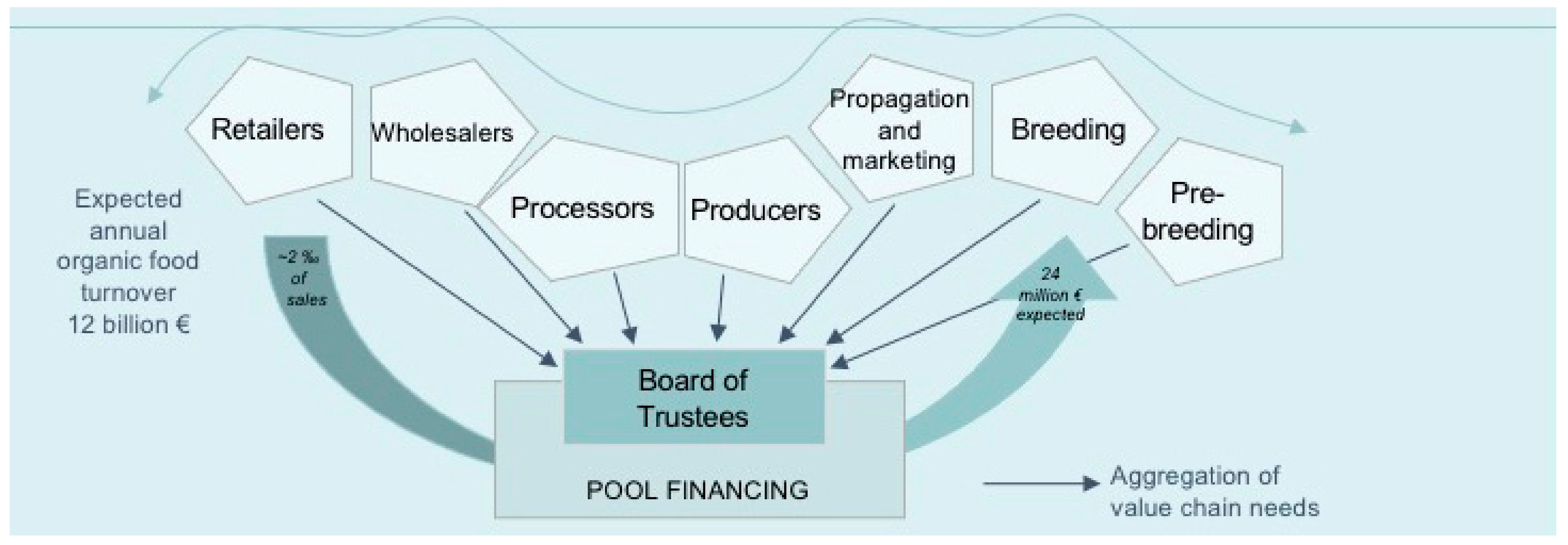

3.3.4. Involving The Food Value Chain

Awareness is growing that organic plant breeding provides overall social and environmental benefits and that it cannot and should not have to finance itself completely. Therefore, investigations are underway to determine how not just growers but also processors, traders and consumers could contribute and thus support organic plant breeding:

An alliance between trade and breeding was established among retailers organised under the umbrella of the association Naturata International–Acting Together and Kultursaat e.V., who started the project FAIR-BREEDING. Retailers who join the initiative channel 0.3% of net sales of organic vegetables and fruit to organic plant-breeding initiatives over ten years [

48].

The Landsorten-Projekt (landraces project) of the Keyserlingk Institut on Lake Constance regularly brings together breeders, farmers, millers and bakers for discussion of outstanding issues regarding production quantities, cultivars and quality. Ten cents per kg from the flour milled from the local wheat cultivars flow back to the breeding initiative [

49].

Figure 4 shows it is still low in all cases, but the initiatives have great potential and send a positive signal to other companies. However, the challenge lies ahead: establishing a financing mechanism that includes the value chain of the food sector as a whole. Efforts in this direction are being made by BOELW (Federation of the Organic Food Industry) in Germany with a fundraising target of approximately 24 million Euros [

50].

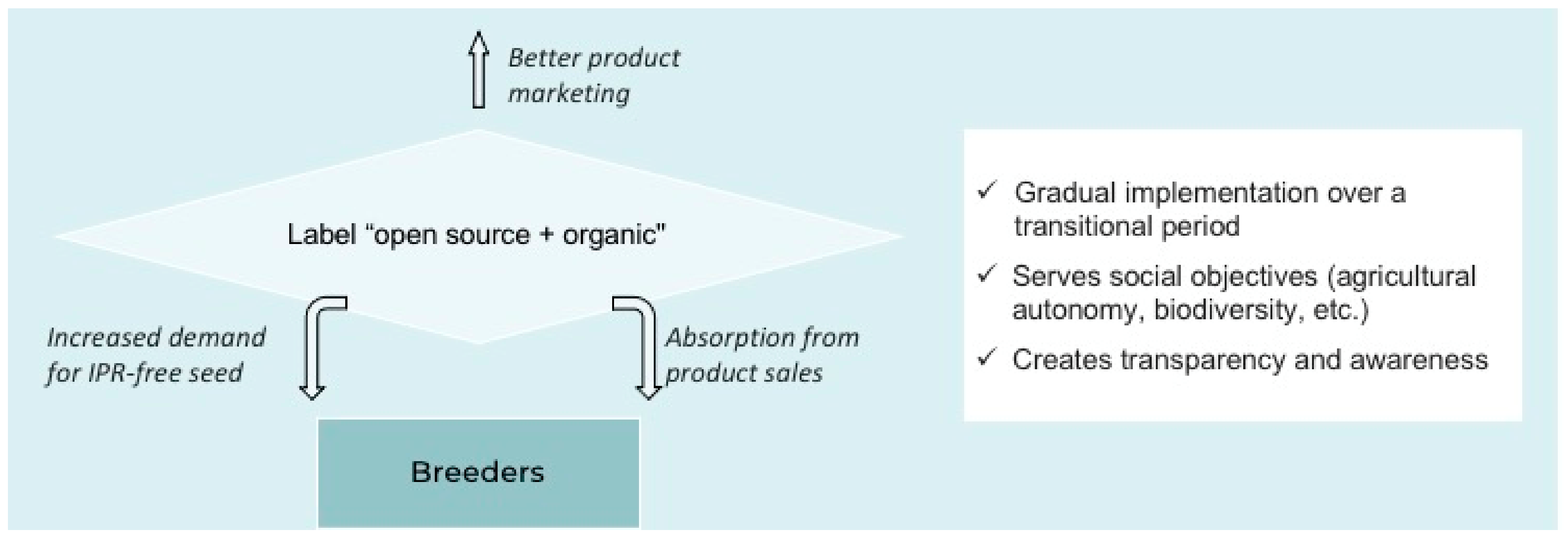

3.3.5. A Label “Open Source and Organic”

Another suggestion from the 2019 workshop on finding alternatives to finance plant breeding was to create a label (

Figure 5). With the “seed as a commons” narrative and open source strategies, a label could be secured as trademark protection for food from organically bred seed and vegetative plant material that cannot be patented or owned under other IPR systems. It could be a way to involve the consumer in financing organic breeding systematically. A fee for using all labelled products would allow considerable sums of money to be generated and invested into commons-based organic plant breeding. In this context, the “open source” attribute gives organic breeding a unique quality and added intrinsic value.

The label would also widen consumer awareness about and support for organic plant breeding. Consumers can create a pull effect [

51,

52]. Demand for commons-based organic seed would increase, and breeders would be encouraged to work according to the open source criteria. Marketing companies could use the label to distinguish their products from the mass. Consumers can take responsibility and make a concrete contribution to an alternative to the conventional seed market. Last but not least, consumers are made aware of the origin of the seed–an aspect related to transparency that has been completely neglected until now. Increasingly, processors and traders may feel obliged to join a trend of selling produce from commons-based organic seed and take the necessary measures step by step.

To implement this, a preparatory phase of at least one year and cooperation with various partners would be necessary. First, an independent organisation must be identified or founded to design and manage the label, develop standards and find partners for certification. A non-profit association could be the appropriate legal entity. At least two larger companies in the food retail trade (supermarket chains) would need to start introducing the label into the market. Others could join later and at any time.

When introducing the label, it would make sense to start with some basic minimum standards and allow breeders to gradually transition into following a full-fledged set of criteria for open source organic plant breeding, for example, over ten years. In order to assure the necessary commitment in this process, appropriate guidelines should be developed and regular inspections made. Although the guidelines would initially allow some tolerance level, the transition period must be set with binding deadlines so that the system can be fully developed by a specific date. The introduction of such a label on the food market could boost the financing of commons-based organic plant breeding.

4. Discussion

Conventional plant breeding cannot provide the required crop diversity. Organised mainly as private enterprises, they depend on IPRs to gain royalties, and they strive for genetic homogeneity and stability of their cultivars, traits that serve as proof of ownership. Alternatively, organic plant breeding has emerged to enhance crop diversity. Thus far, it is a small niche in the seed sector, with remarkable growth, but far from covering the current needs of organic agriculture. It is financed mainly through donations, a limited source of funding.

Our survey among organic plant breeders confirmed that royalties from IPRs contributed little or nothing to financing new cultivars for various reasons. Most organic breeders reject the idea of claiming IPRs and acknowledge that large-scale use of one cultivar contradicts the aim for diversity in cropping systems. Secondly, they realise that the area cropped with new organic cultivars is far too small to generate sufficient income from royalties, even if IPRs were applied.

Generally, there is a strong trend among organic breeders to consider IPRs and crop diversity as being mutually exclusive and to waive IPRs. Instead, they move toward managing newly released cultivars as a common-pool resource without having an alternative financing concept in place. There is consensus among breeders that scarcity of funds is the main constraint to expansion. Breeders depend on donations from private or charitable foundations with limited-term funding cycles and a restricted volume of funds.

Given the comprehensive aims of crop development, plant breeding can be seen as an obligation of society and a service to be financed by all. New cultivars can then be considered a common-pool resource, as a commons that is accessible to all, although not cost-free and subject to certain rules of use to keep them in the public domain. An open source strategy is proposed to protect the organic cultivar and all its derivatives. An open source seed licence is suggested for use.

In online surveys, stakeholders in the food value chain–farmers, millers, bakers and, most important, consumers–held a positive attitude towards an open source for seeds. By far the majority of these stakeholders promoted open source for seed to enhance crop diversity, protect cultivars from privatisation and strengthen organic agriculture. In addition, more than 90% of the consumers surveyed would accept a price premium for food items from open source seed to finance organic open source plant breeding. This indicates significant potential to involve society as a whole in financing plant breeding.

The search for appropriate business concepts rendered the following ideas:

“Community-based plant breeding” is proposed for regional agricultural producer groups, often combined with consumer groups and applied with CSA associations. Such consortia finance breeding programmes, and regionally adapted cultivars are developed primarily for their own purposes.

“Breeding on demand” is entirely service-oriented; it works on clients’ requests and is financed by them. For example, they can be supermarkets that want to offer a special regional product, waterworks that want organic cultivars to be used to keep pesticide and nitrate levels in soils low, or simply a company that wants to make a stronger social commitment to sustainability.

“Outsourcing acquisition” is seen as a possibility for organic breeders to professionalise and enlarge their fundraising efforts. Service providers specialising in breeding programmes’ acquisition, accounting and management may increase scope and efficiency in utilising public funds.

“Involving the food value chain” would include all stakeholders–farmers, processors, wholesalers, retailers and consumers–in financing organic plant breeding. This is the most comprehensive concept to address society as a whole in paying for plant breeding. Organic farming advocacy groups promote it, but a mechanism for each party to take its respective share on a compulsory basis has not yet been agreed upon.

“Introducing a food label open source and organic” could become such a mechanism. A label could make it mandatory for all value chain stakeholders to participate. A fee for using all labelled products would allow considerable sums of money to be generated and invested into commons-based organic plant breeding.

Generally, there is no silver bullet for financing organic plant breeding. Instead, a comprehensive strategy would be composed of a combination of different financing models. Such a strategy requires a coordination mechanism. It is advisable to set up several funds, similar to the seed fund of the Zukunftsstiftung Landwirtschaft (Foundation for Future Farming) [

53]. Several funds for distribution with different aims and purposes of crop development would offer the possibility of competition between funds.

It can be concluded that the concept of seed as a commons offers a viable alternative to IPRs-based private plant breeding. Free access to seed for breeding is a prerequisite for SMEs to exist or to start plant breeding. Organisational diversity in the breeder landscape is essential to develop the urgently needed heterogeneity of efficient crop species and their cultivars. Therefore, a renaissance of SMEs in plant breeding is necessary to counter the growing IPRs-based market concentration.

New ways of financing and thus promoting the growth in organic plant breeding have been developed by using an open source strategy for seeds as commons. The results achieved so far indicate a direction for moving forward. Research and development (R&D) in this direction need to be intensified.