Effects of Façades on Urban Acoustic Environment and Soundscape: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

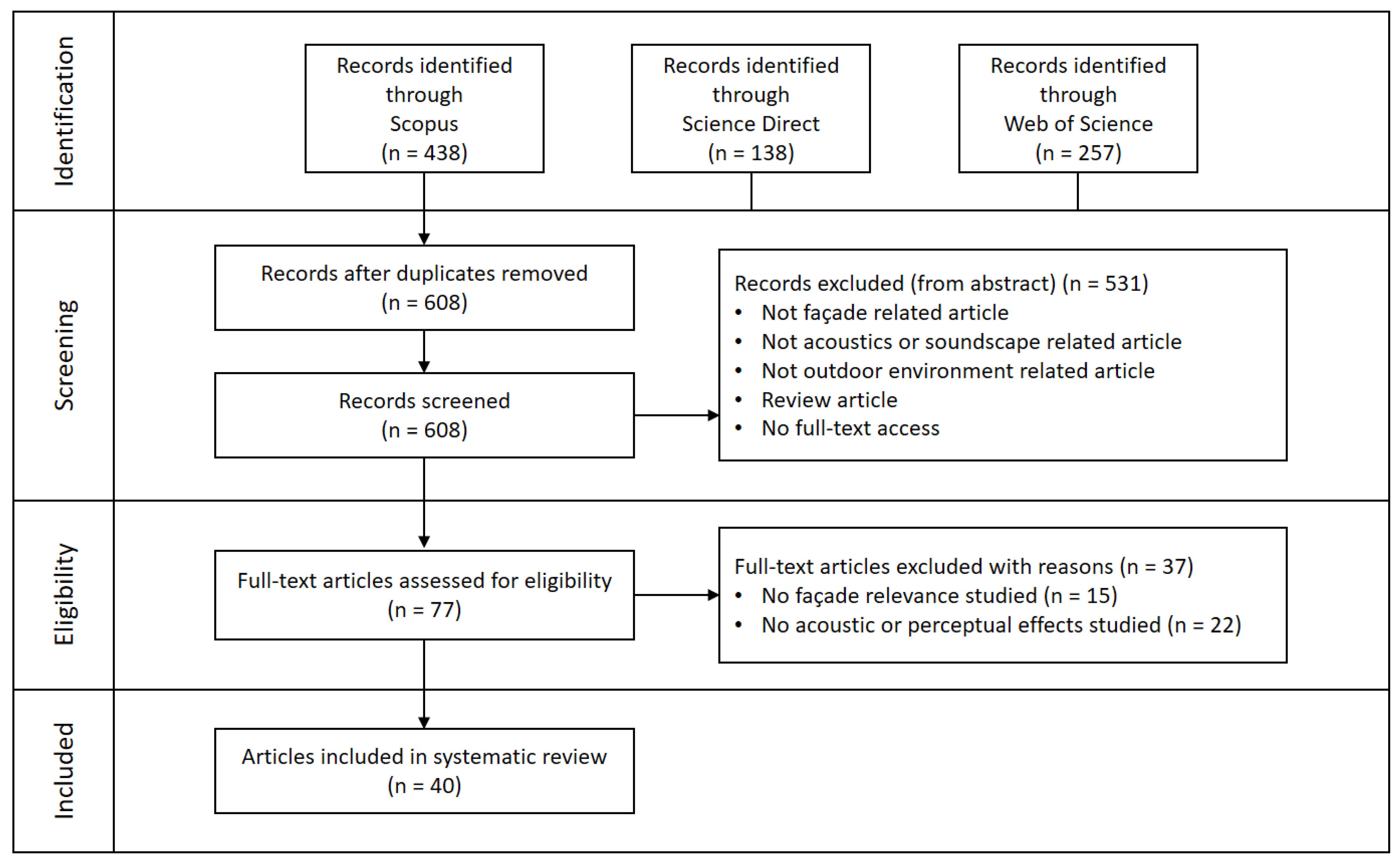

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Reported Effects

3.3. Façade Parameters

3.4. Contextual Parameters

3.4.1. Sound

3.4.2. Path

3.4.3. Receiver

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Façades on the Urban Acoustic Environment

4.1.1. Sound-Reflecting Effects

4.1.2. Sound-Absorbing Effects

4.1.3. Sound-Producing Effects

4.2. Effects of Façades on the Urban Soundscape

4.2.1. Auditory Effects

4.2.2. Non-Auditory Effects

4.3. Effects of the Context on the Acoustic Environment around Façades

4.3.1. Boundary Effects

4.3.2. Atmospheric Effects

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Global Population Growth and Sustainable Development; UN DESA/POP/2021/TR/NO. 2; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2002/49/EC. Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise (END); European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gruebner, O.; Rapp, M.A.; Adli, M.; Kluge, U.; Galea, S.; Heinz, A. Cities and Mental Health. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environment Agency. Environmental Noise in Europe, 2020; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 12913-1:2014; Acoustics–Soundscape–Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Schafer, R.M. The Book of Noise; Price Print: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, R.M. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Southworth, M. The sonic environment of cities. Environ. Behav. 1969, 1, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truax, B. Handbook for Acoustic Ecology; A.R.C. Publications: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 12913-2:2018; Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 2: Data Collection and Reporting Requirements; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO/TS 12913-3:2019, Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 3: Data Analysis; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Krimm, J. Acoustically Effective Façade. Archit. Built Environ. 2018, 16, 1–212. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Jeon, J.Y. Design Strategies and Elements of Building Envelope for Urban Acoustic Environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 182, 107121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, M.; Pellegrino, R.; Scorpio, M.; Maffei, L. Auditory and Visual Impact of Split Systems on the Façade of Historical Buildings. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 178, 107997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesten, J.; Tenpierik, M.; Krimm, J. Sound Predictions in an Urban Context. Build. Acoustics 2022, 29, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes González, D.; Barrigón Morillas, J.M.; Rey Gozalo, G.; Godinho, L. Effect of Parking Lanes on Assessing the Impact of Road Traffic Noise on Building Façades. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, D.; Yadav, M.; Holmes, J.; Fong, O.; Caldwell, H. Incidental Acoustic Retroreflection from Building Façades: Three Instances in Berkeley, Sydney and Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2020, 172, 106733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupeng, W.; Kang, J.; Hong, J. Effects of Urban Street Spatial Parameters on Sound Propagation. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistner, P.; Kaufmann, A.; Koehler, M.; Würth, M.; Hofbauer, W.K.; Dittrich, S. Building Physics Design of Urban Surfaces. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 012067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Ma, H.; Kang, J. A Hybrid Model for Investigating the Effect of Scattering from Building Façade on Sound Propagation in Street Canyons. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, A.; Sievers, T.; Eggenschwiler, K. Acoustic Comfort in Virtual Inner Yards with Various Building Facades. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badino, E.; Manca, R.; Shtrepi, L.; Calleri, C.; Astolfi, A. Effect of Façade Shape and Acoustic Cladding on Reduction of Leisure Noise Levels in a Street Canyon. Build. Environ. 2019, 157, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleri, C.; Shtrepi, L.; Armando, A.; Astolfi, A. Evaluation of the Influence of Building Façade Design on the Acoustic Characteristics and Auditory Perception of Urban Spaces. Build. Acoust. 2018, 25, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.L.; Goehring, A. Aeroacoustic façade noise: Predicting wind-induced noise from perforated façade panels. In Proceedings of the 2018 Building Performance Analysis Conference and SimBuild, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–28 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Montes González, D.; Barrigón Morillas, J.M.; Godinho, L.; Amado-Mendes, P. Acoustic Screening Effect on Building Façades Due to Parking Lines in Urban Environments. Effects in Noise Mapping. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 130, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Kang, J. Effects of Built Environment Morphology on Wind Turbine Noise Exposure at Building Façades. Renew. Energy 2017, 107, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.; Gagliardi, P.; Asensio, C.; Licitra, G. A Case Study of the Influence of Urban Morphology on Aircraft Noise. Acoust. Aust. 2017, 45, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echevarria Sanchez, G.M.; Van Renterghem, T.; Thomas, P.; Botteldooren, D. The Effect of Street Canyon Design on Traffic Noise Exposure along Roads. Build. Environ. 2016, 97, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S.; Kim, H.J.; Jeon, J.Y. Scale-Model Method for Measuring Noise Reduction in Residential Buildings by Vegetation. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, A.; Fortin, N.; Picaut, J. Accounting for the Effect of Diffuse Reflections and Fittings within Street Canyons, on the Sound Propagation Predicted by Ray Tracing Codes. Appl. Acoust. 2015, 96, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, G.; Gauvreau, B.; L’Hermite, P. Numerical Study of the Impact of Vegetation Coverings on Sound Levels and Time Decays in a Canyon Street Model. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 502, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, S.; Aoki, A. Numerical and Experimental Study on Noise Shielding Effect of Eaves/Louvers Attached on Building Façade. Build. Environ. 2015, 94, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S.; Lee, S.C.; Jeon, J.Y.; Kang, J. Evaluation of Road Traffic Noise Abatement by Vegetation Treatment in a 1:10 Urban Scale Model. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2015, 138, 3884–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Kang, J. Influence of Mesoscale Urban Morphology on the Spatial Noise Attenuation of Flyover Aircrafts. Appl. Acoust. 2014, 84, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.T.; Oliveira, M.; Silva, J.F. Urban Form Indicators as Proxy on the Noise Exposure of Buildings. Appl. Acoust. 2014, 76, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Renterghem, T.; Hornikx, M.; Forssen, J.; Botteldooren, D. The Potential of Building Envelope Greening to Achieve Quietness. Build. Environ. 2013, 61, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Van Renterghem, T.; De Boeck, E.; Dragonetti, L.; Botteldooren, D. Reverberation-Based Urban Street Sound Level Prediction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 133, 3929–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornikx, M.; Forssén, J. Modelling of Sound Propagation to Three-Dimensional Urban Courtyards Using the Extended Fourier PSTD Method. Appl. Acoust. 2011, 72, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Piippo, K.E. Sound Fields inside Street Canyons with Inclined Flanking Building Façades. Proc. Meet. Acoust. 2011, 12, 040004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.F.; Silva, L.T. The Influence of Urban Form on Facades Noise Levels. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2011, 7, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, Y.; Yoshihisa, K.; Kuno, K. Simple Calculation Model for Noise Propagation in City Street Canyons Based on a Diffusion Method. Acoust. Sci. Technol. 2010, 31, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hornikx, M.; Forssén, J. Noise Abatement Schemes for Shielded Canyons. Appl. Acoust. 2009, 70, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornikx, M.; Forssén, J. A Scale Model Study of Parallel Urban Canyons. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2008, 94, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaga, H.; Rindel, J.H. Acoustic Characteristics of Urban Streets in Relation to Scattering Caused by Building Facades. Appl. Acoust. 2007, 68, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, D. Three-Dimensional Linearised Euler Model Simulations of Sound Propagation in Idealised Urban Situations with Wind Effects. Appl. Acoust. 2007, 68, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Jeon, J.Y.; Song, K.D. Effects of Apartment Building Façade and Balcony Design on the Reduction of Exterior Noise. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3517–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Renterghem, T.; Salomons, E.; Botteldooren, D. Parameter Study of Sound Propagation between City Canyons with a Coupled FDTD-PE Model. Appl. Acoust. 2006, 67, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsson, P.J.; Ögren, M. Macroscopic Modeling of Urban Traffic Noise—Influence of Absorption and Vehicle Flow Distribution. Appl. Acoust. 2005, 66, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Numerical Modeling of the Sound Fields in Urban Squares. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 117, 3695–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Numerical modelling of the sound fields in urban streets with diffusely reflecting boundaries. J. Sound Vib. 2002, 258, 793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iu, K.K.; Li, K.M. The propagation of sound in narrow street canyons. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002, 112, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picaut, J.; Simon, L. A Scale Model Experiment for the Study of Sound Propagation in Urban Areas. Appl. Acoust. 2001, 62, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, C.H.; Lim, K.B. Facade Effects on the Traffic Noise from the Expressway. Appl. Acoust. 1994, 41, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study Design | Reported Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Method | Objective Measure | Perceptual Attribute | ||

| Masullo et al., 2021 [15] | (a) Naples, Italy; (b) Barcelona, and (c) Valencia, Spain | FM, LE (n = 30) | Leq | Loudness, Noise Annoyance, Visual Pleasantness | • Visual elements that are more integrated (aesthetically) on the façade of historical buildings can reduce the auditory and visual impact of these elements. • Well-integrated and pleasant elements led to a lower auditory perception of the loudness and noise annoyance than less integrated elements. |

| Niesten et al., 2021 [16] | Delft, The Netherlands | SI, FM, SM (1:50) | SPL, Leq | n/a | • Sound reflective design (inclined upwards) reduced SPL by up to 9.3 dB(A). • Sound-absorbing design reduced SPL inside the courtyard area by up to 5.5 dB(A). • Combined design (geometry and absorption) reduced SPL by up to 6.7 dB(A). |

| Montes González et al., 2020 [17] | Don Benito, Spain | SI, FM | SPL, Leq | n/a | • Cars parked near façades act as shielding between the sound source and façade. Differences up to 4 dB(A) in sound levels were found between situations without and with cars parked, in some cases, up to 8 dB(A). |

| Cabrera et al., 2020 [18] | (a) Berkeley, USA; (b) Sydney, Australia; (c) Hong Kong | FM, SI | SPL | n/a | • Acoustic retroreflection (when sound is reflected back to the source) occurs due to façade geometry and is most prominently in the high-frequency range. • While retroreflections are measurable, they are not necessarily audible in noisy environments. |

| Hupeng et al., 2019 [19] | Harbin, China | SI | Sound attenuation, RT30, EDT | n/a | • Sound attenuation is linearly correlated with sound propagation distance. • The mean reverberation time increases with the increasing mean façade height, sidewalk width, and cross-sectional enclosure. |

| Leistner et al., 2019 [20] | n/a | SI | Insertion loss | n/a | • Sound level reduction due to façade absorption. Insertion loss is from 58.6 dB to 52.7 dB. |

| Yu et al., 2019 [21] | Tianjin, China | SI, FM | SPL, RT | n/a | • Scattering coefficient from building façades affects the sound pressure level and reverberation time in street canyons. |

| Taghipour et al., 2019 [22] | Dübendorf, Switzerland | LE (n = 27) | SPL | Short-term acoustic comfort | • Effects of several variables (façade absorption, type of sound, observer position) on short-term acoustic comfort • Façade absorption was found, generally, to increase acoustic comfort. Too much absorption, however, was not found to be helpful. • Significant differences observed between acoustic comfort at distinct observer/listener positions. |

| Badino et al., 2019 [23] | Turin, Italy | SI | SPL | n/a | • Geometrically optimized façade cladded with sound absorbing materials can decrease noise level by up to 10 dB over the façade and up to 3 dB over the opposite one. • Up to 1 dB decrease in the mean level over the entire façade achieved with balconies that have a depth of 1.5 m compared to 0.9 m, with a maximum abatement of 2.8 dB at the highest floor. |

| Calleri et al., 2018 [24] | Turin, Italy | SI, FM, LE (n = 31) | SPL, RT30, C50, DRR | Space wideness | • Absorption and scattering coefficients of façade upholsteries and listener position have an influence on the acoustic characteristics of the square and the subjective assessment of its wideness through auditory perception. • T30 was the most influential parameter on perceived space wideness. |

| Jones and Goehring, 2018 [25] | Pacific Northwest, USA | SI | SPL | n/a | • Pressure fluctuations that result from wind produce noise on the façade’s perforated panels. • Frequency and audibility are influenced by hole diameter, hole spacing, panel thickness, wind velocity, turbulence intensity, and wind angle of incidence. • The corners and the top of the building are the most prone to wind-induced noise. |

| Montes González et al., 2018 [26] | n/a | FM, SI | SPL | n/a | • Noise maps neglect the shielding effects of cars parked in front of buildings. Differences of up to 3 dB with and without parked cars in specific heights along the façade. |

| Qu and Kang, 2017 [27] | North Oxford; Rotherham; Greater London, UK | SI | Leq | n/a | • Considering noise from wind turbines, built environment morphology creates large variations in sound levels (up to 10 dB(A)) around dwellings at building scale in the distant range of 400–1000 m from the source. |

| Flores et al., 2017 [28] | (a) Madrid, Spain; (b) Pisa, Italy | FM | Leq | n/a | • Considering aircraft noise, the orientation of buildings toward fight paths influences sound pressure levels on façades. |

| Echeverria Sanchez et al., 2016 [29] | Ghent, Belgium | SI, FM | SPL | n/a | • Building shape can be responsible for variations of up to 7.0 dB(A) on the pedestrian level. • Building façade design can reduce the average exposure at windows with 12.9 dB(A). • Street geometry can enhance the positive effect of low barriers to 11.3 dB(A) along sidewalks. • Building geometry mainly influences noise levels along the façades, whereas geometrical changes to noise barriers next to the source have a higher relevance for pedestrians and at the windows of lower floors. |

| Jang et al., 2015 [30] | n/a | SI, SM (1:10) | SPL | n/a | • Noise reduction due to the vegetated façades was less than 2 dB at the pedestrian level in a two-lane street canyon. • The noise reduction effect due to the absorption performance was more effective in low-frequency bands than in high-frequency bands, on the basis of 1 kHz. |

| Can et al., 2015 [31] | n/a | SI | SPL | n/a | • Overall sound level increase due to diffusion by up to 10 dB, according to the street geometry and acoustical parameters. • Diffusion by façades and fittings impact sound attenuation within street canyons. |

| Guillaume et al., 2015 [32] | Nantes, France | SI, FM | SPL, EDT | n/a | • Beneficial effect of greening building façades and rooftops in terms of both acoustic level and sound decay time indicators at low-frequency third-octave bands. • The effect of vegetation on sound levels at the façade presents a 5 dB reduction. |

| Sakamoto and Aoki, 2015 [33] | Japan | SI, SM (1:20) | Insertion loss | n/a | • Flat eaves in a horizontal direction attached on upper and lower positions of the story have both positive and negative effects on noise propagation from a source to a receiver: a shading effect by the lower eave and a reflection effect by the upper eave. As a result, the noise reduction is not so high. • Making an upper eave inclined is effective countermeasure for noise reduction because the inclined eave reflects the incident sound outward from the surrounding surface of the building. The noise reduction effect is higher as the receiving point is higher. • Louvers with horizontal short fins are also effective at high stories. |

| Jang et al., 2015 [34] | n/a | SM (1:10) | Insertion loss, RT | n/a | • Vegetated façades mitigated the overall noise level up to 1.6 dB(A) in the street canyon, and greening façades were effective to reduce low frequency noise levels below 1 kHz. • Vegetated façades in street canyon effectively reduced noise below 630 Hz in courtyards. |

| Hao and Kang, 2014 [35] | Assen, the Netherlands | SI | L10, L50, L90, Lavg | n/a | • Within the 1000 m horizontal distance of flight path to a site, urban morphology plays an important role in sound propagation, especially for the buildings with high sound absorption façades, where the variance of average noise level attenuation among different sites is about 4.6 dB at 3150 Hz. • The effect of a flight altitude of 200–400 ft (60–120 m) on average noise level attenuation is about 2 dB at both 630 Hz and 1600 Hz in open areas. |

| Silva et al., 2014 [36] | Braga, Portugal | SI | Leq | n/a | • Influence of the urban form on the noise exposure of building façades. |

| Van Renterghem et al., 2013 [37] | n/a | SI | Insertion Loss | n/a | • Fully vegetating the source canyon does not give additional benefits compared to only treating the upper half in case of soft bricks, while additionally 1 dB(A) can be gained in case of rigid bricks. The presence of wall vegetation in the lower part only results in a rather limited insertion loss. • Insertion loss of 4.4 dB(A) in case of fully vegetated source canyon façades. • Fully vegetating the receiving canyon has an additional advantage compared to only treating the upper half. |

| Thomas et al., 2013 [38] | Ghent, Belgium | FM, SI | SPL, RT | n/a | • An increase in average height generally leads to an increase in SPL. For positions further from the source, the change in the SPL over the average height is bigger than for positions close to the source. |

| Hornikx and Forssén, 2011 [39] | n/a | SI | SPL | n/a | • Noise can increase up to 10 dB(A) in an open courtyard compared to in a closed courtyard. To counteract the impairment due to the façade opening, absorption can be applied to the opening walls at the same time as additional façade absorption. • Opening on façades causes the average level to be up to 7.2 dB(A) higher for the façade receiver positions and up to 10.1 dB(A) higher for the courtyard receiver positions. • Effect of façade absorption of up to 1.5 dB(A). |

| Tang and Piippo, 2011 [40] | n/a | SM (1:4) | SPL, RT | n/a | • The increase in sound level due to the presence of an opposite vertical wall can be as high as 8 dB, probably because of the multiple images effect and the increased reverberation. • As the inclination of one of the wall decreases, the reverberation strength decreases quickly and the sound field becomes less uniform. |

| Oliveira and Silva, 2011 [41] | n/a | SI | Leq | n/a | • The average values of Leq will increase as the number of floors increases. |

| Okada et al., 2010 [42] | n/a | SI, SM (1:40) | SPL | n/a | • Sound pressure levels increase with increasing height of buildings. • Sound pressure levels increase with the viaduct road width and building density. |

| Hornikx and Forssén, 2009 [43] | Göteborg, Sweden | SI | SPL | n/a | • A change in the façade absorption coefficient leads to a reduction of around 4 dB(A) for most canyon observer positions. • Façade absorption is the most effective when placed in the upper part of the canyon. |

| Hornikx and Forssén, 2008 [44] | n/a | SM (1:40) | RT10, SPL | n/a | • Sound propagation in parallel canyons affected by inserting absorption and diffusion patches in the façades of the source canyon. The level differences between rigid façades and applied absorption or diffusion patches are larger in the shielded canyon than in the directly exposed street canyon. |

| Onaga and Rindel, 2007 [45] | n/a | SI | SPL, RT | n/a | • The effect of façade scattering on the SPL appears to increase at short distances and decrease at great distances. The range of the increase in SPL is larger in high-facade streets. In low-facade streets, the primary effect of scattering on SPL is a decrease in SPL. • In low-facade streets, the reverberation time is determined by the sum of absorption coefficient and scattering coefficient. In contrast, in high-façade streets, the reverberation time is determined by the absorption coefficient. |

| Heimann, 2007 [46] | n/a | SI | SPL | n/a | • In parallel streets, façades of flat-roof buildings are quieter than those of hip-roof buildings despite equal cross-cut areas. The wind effect (resulting in quieter upwind and louder downwind façades) is more pronounced for hip-roof buildings. In the case of parallel streets, upwind façades are slightly louder than downwind façades because they are simultaneously exposed to downwind propagating sound from the next parallel street. |

| Lee et al., 2007 [47] | Seoul, Korea | SI, FM, SM (1:50) | SPL, RT20 | n/a | • Studying façades with balconies on a scale model, the combination of absorbing surfaces on the parapet and inclined ceiling provided a maximum noise reduction of 16 dB at 1 kHz. |

| Van Renterghem et al., 2006 [48] | n/a | SI | SPL | n/a | • Diffusely reflecting façades and balconies lead to an important increase in shielding compared to flat façades. Near 1000 Hz, about 10 dB in shielding is gained for the profiled façade (introducing recesses by windows and protrusions by windowsills, together with a roughened wall) • In case of downwind sound propagation, shielding decreases by an important degree compared to a non-moving atmosphere. With increasing incident wind speed and with increasing frequency, shielding decreases. • In case of upwind sound propagation, turbulent scattering plays an important role and shielding does not increase compared to a non-moving atmosphere. |

| Thorsson and Ogren, 2005 [49] | Stockholm, Sweden | SI | Leq, SPL | n/a | • Absorption onto building façades will give lower levels at shielded positions. • Absorptive material can reduce the noise levels by at least 5 dB when located inside the canyons. |

| Kang, 2005 [50] | n/a | SI | SPL, RT, EDT | n/a | • The SPL in far field is typically 6–9 dB lower if the (urban) square side is doubled; 8 dB lower if the height of building façades is decreased from 50 m to 6 m (diffuse boundaries); 5 dB (diffuse boundaries) or 2 dB (geometrical boundaries) lower if the length/width ratio is increased from 1 to 4; and 10–12 dB lower if the boundary absorption coefficient is increased from 0.1 to 0.9. |

| Kang, 2002 [51] | n/a | SI | SPL, RT30 | n/a | • Sound attenuation along the length of the canyon is significant, typically at 20–30 dB/100 m. • Over 2–4 dB extra attenuation can be obtained either by increasing boundary absorption evenly or by adding absorbent patches on the façades or the ground. Reducing building height has a similar effect. • A gap between buildings can provide about 2–3 dB extra sound attenuation, especially in the vicinity of the gap. • The effectiveness of air absorption on increasing sound attenuation along the length could be 3–9 dB at high frequencies. |

| Iu and Li, 2002 [52] | n/a | SI, FM, SM (1:10) | EA, TL | n/a | • Sound propagation in cities involves phenomena, such as reflections and scattering at the building façades, diffusion effects due to recessions and protrusions of building surfaces, geometric spreading, and atmospheric absorption. |

| Picaut and Simon, 2001 [53] | Nantes, France | FM, SM (1:50) | RT, sound attenuation | n/a | • Façade geometry affects reverberation and sound propagation. The architectural (geometrical) complexity of building façades is the fundamental cause of sound diffusion in streets. |

| Chew and Lim, 1994 [54] | Singapore | SI, FM | L10 | n/a | • Buildings on one side of the expressway increase the L10 by 2.5 dB(A) at 1 m from the façade, while buildings on both sides could increase the L10 by more than 10 dB(A). The façade effect is significant only when one is near the buildings. At distances of more than 20 m from the buildings, the façade effect is negligible. • The so-called cannon effect, in which L10 increases with the height of the buildings, is significant only when the buildings are close together, say, less than 20 m apart. The diffuse energy component dominates, increasing the overall L10 by 7–11 dB(A). |

| Reference | Façade Parameters | Contextual Parameters | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry | Materials | Sound | Path | Receiver | |||||||

| Height | Depth, Inclinations | Source | Frequency | BN | Boundary Conditions | Materials | Atmospheric Conditions | Position | Type | ||

| Masullo et al., 2021 [15] | 4 floors | Flat with balconies | RM (Concrete, glass, stone) | AC split units on façade | up tp 10 kHz | Yes | Historic city centers, around 4 floors | RM | n/a | First floor balcony | P (n = 30) |

| Niesten et al., 2021 [16] | 8, 18 floors (50 m) | Flat, angled upwards, balconies | RM, AM | Road traffic | 12.5–31 kHz | Yes | Courtyard between buildings near a busy road, trees | RM, AM (brick, glass, asphalt, grass, water) | 20 °C, 50% | Around the building, height 4 m | I, SI |

| Montes González et al., 2020 [17] | 8 m | Flat | RM | Road traffic | Broadband | Yes | Street with two traffic lanes and parked cars | RM | n/a | Vertically along the façade | I, SI |

| Cabrera et al., 2020 [18] | 24 m | Balconies, recessed windows | RM | Road traffic | 315–12,500 Hz; Simulation: up to 25,900 Hz | Yes | Mid-rise, high-rise | RM, AM | (a) 14 °C, 65%, (b) 21 °C, 59%, (c) 24 °C, 84% | By the sound source | SI, I |

| Hupeng et al., 2019 [19] | 20 m | Flat | RM (Brick with plaster) | Road traffic | 1 kHz | n/a | Canyons in high-density city | RM (asphalt, brick walls with plaster) | n/a | Both sidewalks, height 1.50 m | SI |

| Leistner et al., 2019 [20] | n/a | Flat | RM, AM, VGS | Road traffic | n/a | n/a | Buildings next to motorway | RM | n/a | Mapped around the buildings | SI |

| Yu et al., 2019 [21] | Mid-rise | Flat | RM (rough and fluctuated) | Road traffic | 500 Hz and 1000 Hz | Yes | Canyons | RM (glass, concrete) | 3–12 °C, 72–85% | Central street axis, height 1.25 m | SI, I |

| Taghipour et al., 2019 [22] | up to 7 floors | Flat and balconies | RM, AM | People talking, basketball, children | Broadband | Yes | Courtyard housing complex | RM, AM (brick, glass, concrete, grass) | n/a | Courtyard | P (n = 27) |

| Badino et al., 2019 [23] | 17.8 m | Loggias and balconies | RM, AM | People talking | up to 8000 Hz | n/a | Canyon | RM | n/a | In balconies on both sides of the street height 1.5 m | SI |

| Calleri et al., 2018 [24] | 2–4 floors | Flat and diffusive in multiple orientations | RM, AM, VGS (Plastered brickwork, concrete, green wall) | People talking | 63–8000 Hz | Yes | Public octagonal square (2000 m2) | RM | n/a | On public square | P (n = 31) |

| Jones and Goehring, 2018 [25] | 33 floors | Flat | RM (Perforated metal panels) | Wind | Broadband | Yes | High-rise | RM | Wind (southwest and south, >10 m/s) | On the façade | SI |

| Montes González et al., 2018 [26] | 3 floors | Flat | RM | Road traffic | Broadband | Yes | Single building next to a street with parked cars | RM | n/a | Vertically along the façade, heights 1.5, 4 and 7.3 m | I, SI |

| Qu and Kang, 2017 [27] | 8 m | Flat | RM | Wind turbines | Broadband | n/a | Medium-density neighborhoods | RM | 10 °C, 70% | 0.5 m from façades | SI |

| Flores et al., 2017 [28] | Mostly 2 floors | Flat | RM | Air traffic | n/a | Yes | Mostly two-story buildings near airports | RM, AM | (a) 16.4 °C, 1.9 m/s; (b) 12 °C, 2.7 m/s. | Around buildings and in free field | I |

| Echeverria Sanchez et al., 2016 [29] | 8 floors (25.6 m) | Flat, downwardly inclined, upwardly inclined, convex, concave. | RM, AM (Glass, brick) | Road traffic | Broadband | n/a | Canyons, sound barriers | RM | n/a | Sidewalk | SI, I |

| Jang et al., 2015 [30] | 10 m | Flat | RM, AM, VGS (Glass, brick, green wall) | Road traffic | 1 kHz–40 kHz (scaled 1:10) | n/a | Canyon, two-lane road surrounded by three-floor buildings | RM, AM, VGS | n/a | Parallel to the façade at 1.6 m, height 1.5, 4.5, 7.7, 10.9 m | I, SI |

| Can et al., 2015 [31] | 10–30 m | Flat, diffusive | RM | Road traffic | n/a | n/a | Canyon | RM | Atmospheric absorption | Center of the street | SI |

| Guillaume et al., 2015 [32] | 17, 15 m | Flat | RM, AM, VGS (Concrete, glass, green wall) | Road traffic | up tp 1000 Hz | n/a | Canyon of infinite length | RM | Atmospheric absorption | Along the façade | SI |

| Sakamoto and Aoki, 2015 [33] | 5 floors, 20 floors | Flat with horizontal eaves/louvers | RM (Aluminum eaves/louvers) | Road traffic | up to 2000 Hz | n/a | Mid-rise urban area | RM (MDF board in scale model) | n/a | On the façade between eaves | I, SI |

| Jang et al., 2015 [34] | 3 floors | Flat | RM, AM, VGS (brick, vegetation) | Road traffic | up to 4000 Hz | n/a | Canyon and courtyard | RM, AM (asphalt, brick, heavy grass) | Atmospheric absorption | Sidewalk and courtyard, height 1.5 | I |

| Hao and Kang, 2014 [35] | n/a | Flat | RM, AM (masonry, glass) | Air traffic | 630, 1600 and 3150 Hz | n/a | low-density residential areas | RM | n/a | Mapped around buildings, height 1.6 m | SI |

| Silva et al., 2014 [36] | 4 floors (12 m) | Flat | RM | Road traffic | n/a | n/a | Residential areas | RM, AM | 15 °C, 70% | Grid along the façade | SI |

| Van Renterghem et al., 2013 [37] | 19.2 m | Flat | RM, AM, VGS (Brick, glass, green wall) | Road traffic | Broadband | n/a | Canyon and courtyard | RM | Atmospheric absorption | In the street and along the façades | SI |

| Thomas et al., 2013 [38] | 5–20 m | Flat | RM | Road traffic | 63 Hz–16 kHz | Yes | Canyons (99 streets) | RM | 5.0 °C, 80% | By the sound source | I, SI |

| Hornikx and Forssén, 2011 [39] | 18 m | Flat | RM, AM | Road traffic | up to 500 Hz | n/a | Canyons, courtyard (with gaps) | RM, AM | n/a | Grid in the street and vertically along the façade, height 1.5 m | SI |

| Tang and Piippo, 2011 [40] | 8 m | Flat and inclined at 60°, 70°, 80° | RM | Road traffic | up to 5000 Hz | n/a | Canyon | RM (wood in scale model) | n/a | Along the façade | I |

| Oliveira and Silva, 2011 [41] | 4–8 floors | Flat | RM | Road traffic | n/a | n/a | Buildings between two parallel streets | RM | n/a | Mapped around the buildings | SI |

| Okada et al., 2010 [42] | 30 m | Flat | RM | Road traffic | 250 Hz–1 kHz | n/a | Canyon with viaduct | RM | n/a | Sidewalk, height 1.5 m and 4.5 m | SI, I |

| Hornikx and Forssén, 2009 [43] | 10 m, 20 m | Flat | RM, AM (plaster, glass, brick, wood, plaster) | Road traffic | 100 Hz–1000 Hz | n/a | Canyons | RM | Yes | In the street and along the façades | SI |

| Hornikx and Forssén, 2008 [44] | 20 m | Flat | RM, AM (absorptive and diffusive) | Road traffic | 100 Hz–1000 Hz | n/a | Canyons, courtyard | RM | 20 °C | Sidewalk | I |

| Onaga and Rindel, 2007 [45] | 6, 18, 30 m | Flat | RM, AM | Road traffic | 250 Hz, 2500 Hz | n/a | Canyon | RM | n/a | Sidewalk | SI |

| Heimann, 2007 [46] | 6 m | Flat | RM, AM | Road traffic | 250 Hz | No | Single street and parallel streets | RM, AM | Wind (8 m/s at height 10 m) | Mapped around the building | SI |

| Lee et al., 2007 [47] | 15 floors | Flat and balconies | RM, AM | Road traffic | 500 Hz–1 kHz | Yes | Apartment complex located near a six-lane road. | RM, AM | Atmospheric absorption | In the balconies | SI, I |

| Van Renterghem et al., 2006 [48] | 10 m | Flat, with protrusions, balconies, inclined parapets | RM | Road traffic | up to 1250 Hz | n/a | Canyon | RM | Wind | Mapped around the building | SI |

| Thorsson and Ogren, 2005 [49] | up to 6 floors | Flat | RM, AM | Road traffic | n/a | n/a | Parallel canyons | RM | n/a | On the façade | SI |

| Kang, 2005 [50] | 6–50 m | Flat | RM (diffusive and reflective) | Road traffic | n/a | n/a | Urban squares | RM | Atmospheric absorption | In the square, height 1.2 m | SI |

| Kang, 2002 [51] | 8 m | Flat | RM (diffusive and reflective) | Road traffic | 400 Hz–16 kHz | n/a | Canyon | RM | Atmospheric absorption (20 °C, 40–50%) | In the street | SI |

| Iu and Li, 2002 [52] | 18 m | Flat | RM | Road traffic | up to 6000 Hz | n/a | Canyon | RM (wood in scale model) | Atmospheric absorption | Sidewalk | SI, I |

| Picaut and Simon, 2001 [53] | 8 m, 12 m | Flat | RM (wood in scale model) | Road traffic | 250–5000 Hz | n/a | Canyon (96 m length, 8 m height and 12 m wide) | RM (wood in scale model) | Atmospheric absorption | Along the street | I |

| Chew and Lim, 1994 [54] | 15 floors (45 m) | Flat | RM | Road traffic | 500 Hz | n/a | Canyon | RM | n/a | up to 200 m from façade. Height: 1–5 m | SI |

| Effects of façades on the urban acoustic environment | References |

| Sound-reflecting effects | |

| [16,18,19,23,29,33,38,40,41,42,47,50,53,54] |

| [19,38,40,47,50,53] |

| [21,31,42,44,45,48,50,53,54] |

| [21,45] |

| Sound-absorbing effects | |

| [16,20,22,23,24,30,32,34,35,37,39,43,44,45,47,48,49,50] |

| [24,34,44,45,47,51] |

| Sound-producing effects | |

| [15] |

| [25] |

| Effects of façades on the urban soundscape | References |

| Auditory effects | |

| [24] |

| [22] |

| Non-auditory effects | |

| [15] |

| [15] |

| Effects of the context on the acoustic environment around façades | References |

| Boundary effects | |

| [27,28,29,35,36,39,40,42,44,46,48,51,54] |

| [17,26,29,37,39,44,49] |

| Atmospheric effects | |

| [25,46,48] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balderrama, A.; Kang, J.; Prieto, A.; Luna-Navarro, A.; Arztmann, D.; Knaack, U. Effects of Façades on Urban Acoustic Environment and Soundscape: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159670

Balderrama A, Kang J, Prieto A, Luna-Navarro A, Arztmann D, Knaack U. Effects of Façades on Urban Acoustic Environment and Soundscape: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159670

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalderrama, Alvaro, Jian Kang, Alejandro Prieto, Alessandra Luna-Navarro, Daniel Arztmann, and Ulrich Knaack. 2022. "Effects of Façades on Urban Acoustic Environment and Soundscape: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159670

APA StyleBalderrama, A., Kang, J., Prieto, A., Luna-Navarro, A., Arztmann, D., & Knaack, U. (2022). Effects of Façades on Urban Acoustic Environment and Soundscape: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 14(15), 9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159670