A Holistic Overview of Studies to Improve Group-Based Assessments in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To identify critical themes in the existing literature to facilitate the design and operation of group-based assessments in higher education.

- To identify the present research gaps and provide direction for future research avenues.

2. Group-Based Assessments in Higher Education

3. Research Method

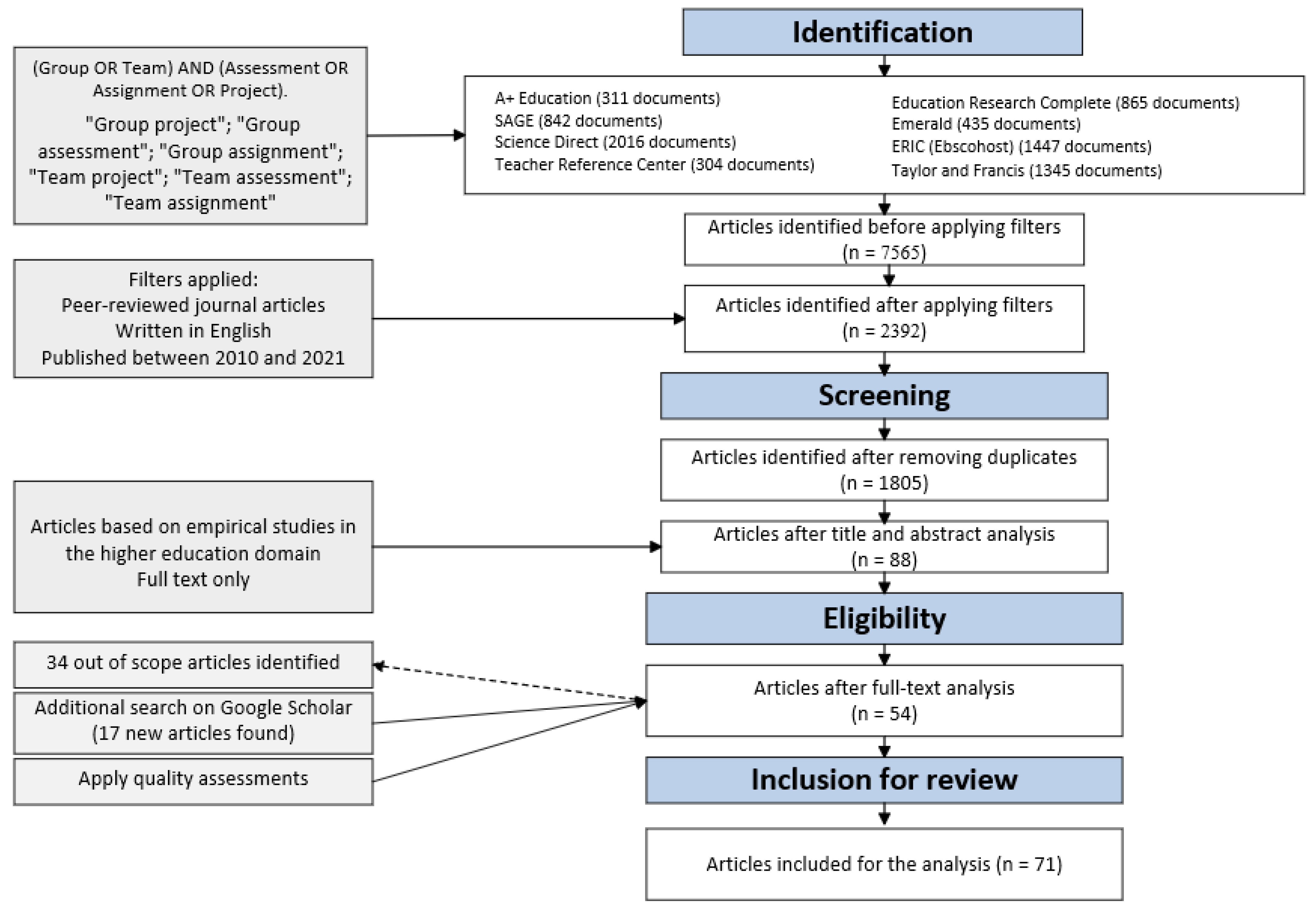

3.1. Stages of SLR

- Q1: Was the research methodology clearly described in the study?

- Q2: Was the data collection method explicitly described in the study?

- Q3: Were the data analysis steps clearly stated in the study?

3.2. Trustworthiness of SLR

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Selected Articles

4.1.1. Countries Contributing to Group-Based Assessment Research

4.1.2. Dominant Research Methods Used in the Selected Articles

4.1.3. Annual Publication Outputs of the Reviewed Articles

4.1.4. Distribution of Publication amongst Journals

4.1.5. Citation Analysis

4.2. Critical Themes That Emerged from Thematic Analysis

4.2.1. Self- and Peer Evaluations

Formative and Summative Peer Assessments

Adjusting Peers’ Marks

Anonymity and Confidentiality in Peer Evaluations

Qualitative and Quantitative Questions in Peer Evaluations

Training for Self- and Peer Evaluations

4.2.2. Group Formation

4.2.3. Group Size

4.2.4. Training for Working in Groups

4.2.5. Academics’ Support and Guidance

4.2.6. Facilitation of Group Work by Technology

5. Future Research

5.1. COVID-19 and Group-Based Assessment Design

5.2. Group Tasks Mapped to Learning Outcomes

5.3. Task Design

5.4. Weightage of Group-Based Assessments

5.5. Group Heterogeneity

5.6. Framework to Design Group-Based Assessments

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Title | Report as systematic literature review. |

| Abstract | Include title as systematic review, background, methods, result, discussion, and others, including funding and registration. |

| Introduction | Provide a justification for this research in existing research, include the objectives of the research and research questions. |

| Methods | Identify eligibility criteria, sources of the data collection, search strategy, selection and data collection process, types of data collected, bias assessment, and data analysis method. |

| Results | Include the detailed process of the search and selection process, including number of records found in each stage, study characteristics, bias in studies, results of studies, syntheses process, and reporting bias. |

| Discussion | Provide the interpretation of the results, limitations of studies included, limitations of the review process, and practical implications. |

| Other information | Mention registration information, financial and non-financial support, competing interests, availability of data, code, and other materials. |

| Reference Number | Article with Author(s) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Eliot, Howard, Nouwens, Stojcevski, Mann, Prpic, Gabb, Venkatesan, and Kolmos [72] |

| 2 | Bong and Park [94] |

| 3 | Paterson and Prideaux [14] |

| 4 | Lockeman, Dow, and Randell [85] |

| 5 | Sridharan and Boud [96] |

| 6 | Ko [82] |

| 7 | Wu, Chanda, and Willison [83] |

| 8 | Friess and Goupee [88] |

| 9 | Sridharan, Tai, and Boud [71] |

| 10 | Caple and Bogle [55] |

| 11 | Fete, Haight, Clapp, and McCollum [87] |

| 12 | Handayani and Genisa [51] |

| 13 | Jin [80] |

| 14 | Melville [76] |

| 15 | Harding [98] |

| 16 | Anson and Goodman [65] |

| 17 | Cen, Ruta, Powell, Hirsch, and Ng [61] |

| 18 | Kooloos, Klaassen, Vereijken, Van Kuppeveld, Bolhuis, and Vorstenbosch [66] |

| 19 | Monson [103] |

| 20 | Moore and Hampton [53] |

| 21 | Spatar, Penna, Mills, Kutija, and Cooke [84] |

| 22 | Takeda and Homberg [64] |

| 23 | Lavy and Yadin [123] |

| 24 | Monson [15] |

| 25 | Swaray [101] |

| 26 | Strauss, U, and Young [62] |

| 27 | Plastow, Spiliotopoulou, and Prior [95] |

| 28 | Postlethwait [90] |

| 29 | Lam [67] |

| 30 | Gransberg [79] |

| 31 | Dommeyer [124] |

| 32 | Sprague, Wilson, and McKenzie [81] |

| 33 | Moraes, Michaelidou, and Canning [93] |

| 34 | Nepal [125] |

| 35 | Mi and Gould [113] |

| 36 | Maiden and Perry [10] |

| 37 | Román-Calderón, Robledo-Ardila, and Velez-Calle [89] |

| 38 | Shiu, Chan, Lam, Lee, and Kwong [86] |

| 39 | Parratt, Fahy, and Hastie [107] |

| 40 | Skelley, Firth, and Kendrach [97] |

| 41 | Sahin [99] |

| 42 | Adwan [74] |

| 43 | Lee, Ahonen, Navarette, and Frisch [77] |

| 44 | Ohaja, Dunlea, and Muldoon [54] |

| 45 | Smith and Rogers [126] |

| 46 | Biesma, Kennedy, Pawlikowska, Brugha, Conroy, and Doyle [92] |

| 47 | Augar, Woodley, Whitefield, and Winchester [100] |

| 48 | Wagar and Carroll [127] |

| 49 | Aaron, McDowell, and Herdman [106] |

| 50 | Planas Lladó, Soley, Fraguell Sansbelló, Pujolras, Planella, Roura-Pascual, Suñol Martínez, and Moreno [50] |

| 51 | Willey and Gardner [59] |

| 52 | Bailey, Barber, and Ferguson [110] |

| 53 | Ding, Bosker, Xu, Rugers, and Heugten [104] |

| 54 | Delaney, Fletcher, Cameron, and Bodle [108] |

| 55 | Dingel and Wei [128] |

| 56 | McClure, Webber, and Clark [91] |

| 57 | Adachi, Tai, and Dawson [58] |

| 58 | Demir [129] |

| 59 | Lubbers [130] |

| 60 | Orr [63] |

| 61 | Agarwal and Rathod [131] |

| 62 | Thondhlana and Belluigi [132] |

| 63 | ONeill et al. [133] |

| 64 | Mostert and Snowball [60] |

| 65 | Vaughan et al. [134] |

| 66 | D’Eon and Trinder [135] |

| 67 | Weaver and Esposto [70] |

| 68 | Guzmán [136] |

| 69 | Warhuus et al. [137] |

| 70 | Rienties, Alcott, and Jindal-Snape [68] |

| 71 | Volkov and Volkov [69] |

References

- AAGE. Australian Association of Graduate Employers. Available online: https://aage.com.au/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Riebe, L.; Roepen, D.; Santarelli, B.; Marchioro, G. Teamwork: Effectively teaching an employability skill. Educ. + Train. 2010, 52, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebe, L.; Girardi, A.; Whitsed, C. Teaching teamwork in Australian university business disciplines: Evidence from a systematic literature review. Iss. Educ. Res. 2017, 27, 134–150. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, C.; Jackson, G.; Lane, J. Talent Is Not Enough; Canada West Foundation: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forsell, J.; Frykedal, K.F.; Chiriac, E.H. Group Work Assessment: Assessing Social Skills at Group Level. Small Group Res. 2019, 51, 87–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, E.; van Deursen, A.J.; van Dijk, J.A.; de Haan, J. Determinants of 21st-century skills and 21st-century digital skills for workers: A systematic literature review. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019900176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.M. Groupwork as a form of assessment: Common problems and recommended solutions. High. Educ. 2009, 58, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, P.L. The Goal Project: A Group Assignment to Encourage Creative Thinking, Leadership Abilities and Communication Skills. Account. Educ. 2014, 23, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, J.; Latijnhouwers, M.; Norbart, A.; Tio, R.A. Assessing the “I” in group work assessment: State of the art and rec-ommendations for practice. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiden, B.; Perry, B. Dealing with free-riders in assessed group work: Results from a study at a UK university. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.-A.; Boyd, S. A Preliminary Evaluation of Using WebPA for Online Peer Assessment of Collaborative Performance by Groups of Online Distance Learners. Int. J. E-Learn. Dist. Educ. 2015, 30, n2. [Google Scholar]

- Forsell, J.; Frykedal, K.F.; Chiriac, E.H. Teachers’ perceived challenges in group work assessment. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8, 1886474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebe, L.; Girardi, A.; Whitsed, C. A Systematic Literature Review of Teamwork Pedagogy in Higher Education. Small Group Res. 2016, 47, 619–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, T.; Prideaux, M. Exploring collaboration in online group based assessment contexts: Undergraduate Business Program. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2020, 17, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Monson, R. Groups That Work: Student Achievement in Group Research Projects and Effects on Individual Learning. Teach. Sociol. 2017, 45, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearnley, C.; Rhodes, C.; Roberts, P.; Williams, P.; Prenton, S. Team based learning in nursing and midwifery higher education; a systematic review of the evidence for change. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 60, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2017, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S.; Scholten, R. Maintaining reviews: Updates, amendments and feedback. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Keele, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; EBSE Technical Report, Version 2.3; Keele University: Keele, UK; University of Durham: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-M.; Kuo, C.-H. An optimized group formation scheme to promote collaborative problem-based learning. Comput. Educ. 2019, 133, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, J. Student-initiated group management strategies for more effective and enjoyable group work experiences. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2010, 9, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, C. A Briefing on Assessment of Large Groups; LTSN: York, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.; Gale, A.; Brown, M.; Khan, A. The importance of human skills in project management professional development. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2010, 3, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. An Educational Psychology Success Story: Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-M. The relationships between higher order thinking skills, cognitive density, and social presence in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 2014, 21, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 2001, 15, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. The Effect of Collaborative Learning on Enhancing Student Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Khaskheli, A.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, F.; Colnerud, G. Teachers’ Experiences of Unfair Grading. Educ. Assess. 2015, 20, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.; Zamora, M.; Best, L. Practical Insights on the Pedagogy of Group Work. Res. Teach. Dev. Educ. 2005, 22, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, L.M.; Valle, B.E. Social Constructivist Teaching Strategies in the Small Group Classroom. Small Group Res. 2013, 44, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; O’Brien, C.L. Social loafing on group projects: Structural antecedents and effect on student satisfaction. J. Mark. Educ. 2008, 30, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R. Groupwork and Assessment: The Handbook for Economics Lecturers; Economics Network: Bristol, UK, 2004; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, M. Are group assignments effective pedagogy or a waste of time? A review of the literature and implications for practice. Teach. Public Adm. 2020, 38, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbiri, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Chileshe, N.; Statsenko, L. A Novel Taxonomy for Risks in Agribusiness Supply Chains: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi, M.; Morales, K.; Lindsey, A. Impact of experiential dementia care learning on knowledge, skills and attitudes of nursing students: A systematic literature review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 62, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araújo, M.C.B.; Alencar, L.H.; Mota, C.M.D.M. Project procurement management: A structured literature review. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewickrama, M.; Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R.; Ochoa, J.J. Quality assurance in reverse logistics supply chain of demolition waste: A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2020, 39, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Philbin, S.P. Systematic literature review of project manager’s leadership competencies. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, N. Social Media Marketing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Master’s Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G.; Pilotta, J. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zachary, K.F. Caregiver Burden with Alzheimer’s and Dementia Patients: A Systematic Literature Review. Ph.D. Thesis, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, S.A. Strategies to Combat Elder Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arizona Global Campus, Chandler, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C. A guide to conducting a standalone systematic literature review. Commun. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 2015, 37, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeft, R. Confidence Issues during Athletic Injury Recovery: A Systematic Literature Review. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arizona Global Campus, Chandler, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario, M.M. Voir Dire Suitability: A Comprehensive Systematic Literature Review of the Jury Selection; University of Arizona Global Campus: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, T.; Khan, F.; Zuo, M.J. A bibliometric analysis of process system failure and reliability literature. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 106, 104152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lladó, A.P.; Soley, L.F.; Sansbelló, R.M.F.; Pujolras, G.A.; Planella, J.P.; Roura-Pascual, N.; Martínez, J.J.S.; Moreno, L.M.; Planas, A. Student perceptions of peer assessment: An interdisciplinary study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2013, 39, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, R.D.; Genisa, M.U. Triyanto. Empowering Physics Students’ Performance in a Group Discussion through Two Types of Peer Assessment. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 655–668. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie, G.A.; Gahan, L.R.; Matthews, K.E.; Weaver, G.C.; Bailey, C.; Adams, P.; Kavanagh, L.J.; Long, P.D.; Taylor, M. Technology Supported Facilitation and Assessment of Small Group Collaborative Inquiry Learning in Large First-Year Classes. J. Learn. Des. 2014, 7, 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, P.; Hampton, G. ‘It’sa bit of a generalisation, but…’: Participant perspectives on intercultural group assessment in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohaja, M.; Dunlea, M.; Muldoon, K. Group marking and peer assessment during a group poster presentation: The experiences and views of midwifery students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2013, 13, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caple, H.; Bogle, M. Making group assessment transparent: What wikis can contribute to collaborative projects. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2011, 38, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Yue, W.L.; Le Vu, H. Visualization and analysis of mapping knowledge domain of road safety studies. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 118, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, C. Emerging trends and new developments in information science: A document co-citation analysis (2009–2016). Scientometrics 2018, 115, 869–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, C.; Tai, J.H.-M.; Dawson, P. Academics’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of self and peer assessment in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 43, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willey, K.; Gardner, A. Investigating the capacity of self and peer assessment activities to engage students and promote learning. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2010, 35, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, M.; Snowball, J.D. Where angels fear to tread: Online peer-assessment in a large first-year class. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, L.; Ruta, D.; Powell, L.; Hirsch, B.; Ng, J. Quantitative approach to collaborative learning: Performance prediction, individual assessment, and group composition. Int. J. Comput. Collab. Learn. 2016, 11, 187–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, P.; U, A.; Young, S. ‘I know the type of people I work well with’: Student anxiety in multicultural group projects. Stud. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, S. Collaborating or fighting for the marks? Students’ experiences of group work assessment in the creative arts. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Homberg, F. The effects of gender on group work process and achievement: An analysis through self- and peer-assessment. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 40, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, R.; Goodman, J.A. A Peer Assessment System to Improve Student Team Experiences. J. Educ. Bus. 2013, 89, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooloos, J.G.; Klaassen, T.; Vereijken, M.; Van Kuppeveld, S.; Bolhuis, S.; Vorstenbosch, M. Collaborative group work: Effects of group size and assignment structure on learning gain, student satisfaction and perceived participation. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C. The Role of Communication and Cohesion in Reducing Social Loafing in Group Projects. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2015, 78, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Alcott, P.; Jindal-Snape, D. To let students self-select or not: That is the question for teachers of culturally diverse groups. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2014, 18, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.; Volkov, M. Teamwork benefits in tertiary education: Student perceptions that lead to best practice assessment design. Educ. + Train. 2015, 57, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.; Esposto, A. Peer assessment as a method of improving student engagement. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, B.; Tai, J.; Boud, D. Does the use of summative peer assessment in collaborative group work inhibit good judgement? High. Educ. 2019, 77, 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliot, M.; Howard, P.; Nouwens, F.; Stojcevski, A.; Mann, L.; Prpic, J.K.; Gabb, R.; Venkatesan, S.; Kolmos, A. Developing a conceptual model for the effective assessment of individual student learning in team-based subjects. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2012, 18, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, J. Assessment of Individual Student Performance in Online Team Projects. J. Asynchron. Learn. Netw. 2011, 15, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adwan, J. Dynamic online peer evaluations to improve group assignments in nursing e-learning environment. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 41, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, R.; Lejk, M. Enhancing student learning, participation and accountability in undergraduate group projects through peer assessment. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2013, 27, 368–382. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, A. “The Group Must Come First Next Time”: Students’ Self-Assessment of Groupwork in a First-Year Criminal Justice Topic. J. Crim. Justice Educ. 2020, 31, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Ahonen, K.; Navarette, E.; Frisch, K. Successful student group projects: Perspectives and strategies. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2015, 10, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, T.M.; Sanders, T.; Bundy, C. The impact of teamwork in peer assessment: A qualitative analysis of a group exercise at a UK medical school. Biosci. Educ. 2010, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gransberg, D.D. Quantifying the Impact of Peer Evaluations on Student Team Project Grading. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2010, 6, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-H. A comparative study of effectiveness of peer assessment of individuals’ contributions to group projects in under-graduate construction management core units. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, M.; Wilson, K.F.; McKenzie, K.S. Evaluating the quality of peer and self evaluations as measures of student contributions to group projects. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-S. Peer assessment in group projects accounting for assessor reliability by an iterative method. Teach. High. Educ. 2013, 19, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chanda, E.; Willison, J. Implementation and outcomes of online self and peer assessment on group based honours research projects. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2013, 39, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatar, C.; Penna, N.; Mills, H.; Kutija, V.; Cooke, M. A robust approach for mapping group marks to individual marks using peer assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2014, 40, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockeman, K.S.; Dow, A.W.; Randell, A.L. Notes from the Field: Evaluating a Budget-Based Approach to Peer Assessment for Measuring Collaboration Among Learners on Interprofessional Teams. Eval. Health Prof. 2019, 43, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiu, A.T.; Chan, C.W.; Lam, P.; Lee, J.; Kwong, A.N. Baccalaureate nursing students’ perceptions of peer assessment of individual contributions to a group project: A case study. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fete, M.G.; Haight, R.; Clapp, P.; Mccollum, M. Peer Evaluation Instrument Development, Administration, and Assessment in a Team-based Learning Curriculum. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friess, W.A.; Goupee, A.J. Using Continuous Peer Evaluation in Team-Based Engineering Capstone Projects: A Case Study. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2020, 63, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Calderón, J.P.; Robledo-Ardila, C.; Velez-Calle, A. Global virtual teams in education: Do peer assessments motivate student effort? Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 70, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postlethwait, A.E. Group projects in social work education: The influence of group characteristics and moderators on un-dergraduate student outcomes. J. Teach. Soc. Work 2016, 36, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, C.; Webber, A.; Clark, G.L. Peer Evaluations in Team Projects: What a Major Disconnect Between Students and Business Instructors. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2015, 15, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Biesma, R.; Kennedy, M.-C.; Pawlikowska, T.; Brugha, R.; Conroy, R.; Doyle, F. Peer assessment to improve medical student’s contributions to team-based projects: Randomised controlled trial and qualitative follow-up. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C.; Michaelidou, N.; Canning, L. Students’ Attitudes toward a Group Coursework Protocol and Peer Assessment System. Ind. High. Educ. 2016, 30, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, J.; Park, M.S. Peer assessment of contributions and learning processes in group projects: An analysis of information technology undergraduate students’ performance. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastow, N.; Spiliotopoulou, G.; Prior, S. Group assessment at first year and final degree level: A comparative evaluation. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2010, 47, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, B.; Boud, D. The effects of peer judgements on teamwork and self-assessment ability in collaborative group work. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 44, 894–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelley, J.W.; Firth, J.M.; Kendrach, M.G. Picking teams: Student workgroup assignment methods in U.S. schools of pharmacy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2015, 7, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, L.M. Students of a Feather “Flocked” Together: A Group Assignment Method for Reducing Free-Riding and Improving Group and Individual Learning Outcomes. J. Mark. Educ. 2017, 40, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Y.G. A team building model for software engineering courses term projects. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augar, N.; Woodley, C.J.; Whitefield, D.; Winchester, M. Exploring academics’ approaches to managing team assessment. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaray, R. An evaluation of a group project designed to reduce free-riding and promote active learning. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2011, 37, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhu, M.; Tam, V.W.; Yi, G.; Tran, C.N. A system dynamics-based environmental benefit assessment model of con-struction waste reduction management at the design and construction stages. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, R.A. Do they have to like it to learn from it? Students’ experiences, group dynamics, and learning outcomes in group research projects. Teach. Sociol. 2019, 47, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Bosker, R.; Xu, X.; Rugers, L.; Van Heugten, P.P. International Group Heterogeneity and Students’ Business Project Achievement. J. Teach. Int. Bus. 2015, 26, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbeck, C.L.; Campbell, S.E.; Bjorklund, S.A. Grouping in the Dark: What College Students Learn from Group Projects. J. High. Educ. 2000, 71, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, J.R.; McDowell, W.C.; Herdman, A.O. The Effects of a Team Charter on Student Team Behaviors. J. Educ. Bus. 2014, 89, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parratt, J.A.; Fahy, K.M.; Hastie, C.R. Midwifery students’ evaluation of team-based academic assignments involving peer-marking. Women Birth 2014, 27, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Delaney, D.A.; Fletcher, M.; Cameron, C.; Bodle, K. Online self and peer assessment of team work in accounting education. Account. Res. J. 2013, 26, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Rapp, T. Laying the foundation for successful team performance trajectories: The roles of team charters and performance strategies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.; Barber, L.K.; Ferguson, A.J. Promoting perceived benefits of group projects: The role of instructor contributions and intragroup processes. Teach. Psychol. 2015, 42, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, K. Students’ Perceptions Concerning Emergency Remote Teaching during COVID-19: A Case Study between Higher Education Institutions in Thailand and Finland. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2021, 20, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, K.; Donelan, H.; Williams, J. Using wikis for online group projects: Student and tutor perspectives. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2014, 15, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mi, M.; Gould, D. Wiki Technology Enhanced Group Project to Promote Active Learning in a Neuroscience Course for First-Year Medical Students: An Exploratory Study. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2014, 33, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Yadav, S.S. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Higher Education and Research. Ind. J. Hum. Dev. 2020, 14, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.A.; Barros, A.; Simão, A.M.V.; Pereira, D.; Flores, P.; Fernandes, E.; Costa, L.; Ferreira, P.C. Portuguese higher ed-ucation students’ adaptation to online teaching and learning in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Personal and contextual factors. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Onge, C.; Ouellet, K.; Lakhal, S.; Dubé, T.; Marceau, M. COVID-19 as the tipping point for integrating e-assessment in higher education practices. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 53, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P. Assessing collaborative learning: Big data, analytics and university futures. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, J.T.; Anderson, R.E. Free-Riding in Group Projects: Control Mechanisms and Preliminary Data. J. Mark. Educ. 1990, 12, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.M.; Williams, K.D. Social loafing on difficult tasks: Working collectively can improve performance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bree, R.; Cooney, C.; Maguire, M.; Morris, P.; Mullen, P. An institute-wide framework for assessed group work: Development and initial implementation in an Irish Higher Education Institution. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2019, 4, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, L.; Birt, J.; Hancock, P.; Schonfeldt, N.; Agrawal, P. Best practices for group assessment tasks. J. Account. Educ. 2022, 59, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, I.; Yadin, A. Team-based peer review as a form of formative assessment-the case of a systems analysis and design workshop. J. Inform. Syst. Educ. 2010, 22, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Dommeyer, C.J. A new strategy for dealing with social loafers on the group project: The segment manager method. J. Mark. Educ. 2012, 34, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, K.P. An approach to assign individual marks from a team mark: The case of Australian grading system at universities. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Rogers, J. Understanding nursing students’ perspectives on the grading of group work assessments. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2013, 14, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagar, T.H.; Carroll, W.R. Examining Student Preferences of Group Work Evaluation Approaches: Evidence from Business Management Undergraduate Students. J. Educ. Bus. 2012, 87, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, M.; Wei, W. Influences on peer evaluation in a group project: An exploration of leadership, demographics and course performance. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2013, 39, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M. Using online peer assessment in an Instructional Technology and Material Design course through social media. High. Educ. 2017, 75, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, C.A. An assessment of predictors of student peer evaluations of team work in the capstone campaigns course. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Rathod, U. Defining ‘success’ for software projects: An exploratory revelation. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thondhlana, G.; Belluigi, D.Z. Students’ reception of peer assessment of group-work contributions: Problematics in terms of race and gender emerging from a South African case study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2016, 42, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oneill, T.A.; Boyce, M.; McLarnon, M.J.W. Team Health and Project Quality Are Improved When Peer Evaluation Scores Affect Grades on Team Projects. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, B.; Yoxall, J.; Grace, S. Peer assessment of teamwork in group projects: Evaluation of a rubric. Iss. Educ. Res. 2019, 29, 961–978. [Google Scholar]

- D’Eon, M.F.; Trinder, K. Evidence for the Validity of Grouped Self-Assessments in Measuring the Outcomes of Educational Programs. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 37, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, S.G. Monte Carlo evaluations of methods of grade distribution in group projects: Simpler is better. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 43, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhuus, J.P.; Günzel-Jensen, F.; Robinson, S.; Neergaard, H. Teaming up in entrepreneurship education: Does the team formation mode matter? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 1913–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Any scholarly article published in peer-reviewed journals | Conference proceedings, reports, book chapters, and dissertations were excluded. |

| Articles based on empirical studies | Any non-empirical studies, such as review papers, were excluded from this review. |

| Any study which is in the higher education domain | Studies related to primary school, secondary education, vocational education, training, and workplace sectors were excluded. |

| Full text only | In order to read and understand the full findings of the article. |

| In the year range (2010–2021) | The scoping review suggests that a considerable number of publications are available from the last decade. |

| Described in English | The authors’ inability to interpret other languages. |

| Research Methods | No of Articles | |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative/Quantitative/Mixed | Detailed Methods | |

| Quantitative (52 articles) | Survey/questionnaire | 33 |

| Retrospective data (students’ grades, quiz scores, self- and peer assessment results) | 11 | |

| Statistical modelling/quasi-experiment | 8 | |

| Mixed (11 articles) | Survey and focus group | 4 |

| Pre-/post-questionnaires, artefacts of the group processes, and student focus groups | 1 | |

| Interviews, observation, and survey | 1 | |

| Interviews, observation, and observation | 1 | |

| Peer assessment scores and focus groups | 1 | |

| Literature review and survey and focus group | 1 | |

| Surveys, focus group interviews, and individual staff interviews | 1 | |

| Survey and course grade | 1 | |

| Qualitative (8 articles) | Interviews | 5 |

| Reflection data | 2 | |

| Focus group | 1 | |

| Journal | Number of Publications per Journal |

|---|---|

| Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education | 19 |

| Journal of Education for Business | 3 |

| Nurse Education in Practice | 2 |

| Nurse Education Today | 2 |

| Teaching Sociology | 2 |

| Higher Education | 2 |

| No | Articles | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adachi, Tai, and Dawson [58] | 160 |

| 2 | Planas Lladó, Soley, Fraguell Sansbelló, Pujolras, Planella, Roura-Pascual, Suñol Martínez, and Moreno [50] | 153 |

| 3 | Willey and Gardner [59] | 152 |

| 4 | Maiden and Perry [10] | 138 |

| 5 | Mostert and Snowball [60] | 100 |

| 6 | Cen et al. [61] | 94 |

| 7 | Strauss et al. [62] | 93 |

| 8 | Orr [63] | 90 |

| 9 | Takeda and Homberg [64] | 88 |

| 10 | Anson and Goodman [65] | 87 |

| 11 | Kooloos et al. [66] | 86 |

| 12 | Lam [67] | 85 |

| 13 | Rienties et al. [68] | 80 |

| 14 | Volkov and Volkov [69] | 80 |

| 15 | Moore and Hampton [53] | 76 |

| 16 | Weaver and Esposto [70] | 67 |

| 17 | Caple and Bogle [55] | 67 |

| 18 | Sridharan et al. [71] | 66 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tumpa, R.J.; Skaik, S.; Ham, M.; Chaudhry, G. A Holistic Overview of Studies to Improve Group-Based Assessments in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159638

Tumpa RJ, Skaik S, Ham M, Chaudhry G. A Holistic Overview of Studies to Improve Group-Based Assessments in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159638

Chicago/Turabian StyleTumpa, Roksana Jahan, Samer Skaik, Miriam Ham, and Ghulam Chaudhry. 2022. "A Holistic Overview of Studies to Improve Group-Based Assessments in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159638

APA StyleTumpa, R. J., Skaik, S., Ham, M., & Chaudhry, G. (2022). A Holistic Overview of Studies to Improve Group-Based Assessments in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(15), 9638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159638