1. Introduction

European Union (EU) law does not oblige micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to produce CSR reports. Research has shown that this is one of the reasons that few SMEs have a good understanding of the CSR concept and what its benefits are [

1]. In legal regulations, the concept of CSR first appeared in the ISO 26000 standard Guidance on social responsibility published in 2010. This standard provides guidance on social responsibility, defined as the responsibility of an organization for the impact of its decisions and actions on society and the environment, through transparent and ethical behaviors. According to the ISO 26000 standard, CSR is a concept, with no obligation to implement it in an enterprise: it is not a form of certification or mandatory regulation. The enterprise itself determines the scope and form of its activities for the benefit of its stakeholders [

2]. In 2011, the EC concluded that the complexity of the mechanism for integrating social, environmental, ethical, and human rights considerations will mean that the CSR mechanism is likely to remain informal and intuitive for most small- and medium-sized companies, particularly micro-enterprises [

3].

The EC’s draft CSRD (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive), which is part of a package of legislative changes for the sustainable financing of economic growth, provides for the introduction of an obligation to report on ESG (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) issues in a measurable form by all companies listed on EU-regulated markets (with the exception of listed micro-enterprises) [

4]. According to this draft, companies, including SMEs listed on EU-regulated markets, will be required to apply EU sustainability reporting standards and to seek attestation of the information provided. Other companies, which include most SMEs, may choose to report ESG issues on a voluntary basis. The EC is preparing reporting standards for SMEs tailored to their capabilities and resources.

In accordance with the CSRD, companies with up to 500 employees, and from 2023, up to 249 employees, are formally exempted from reporting ESG factors, and the proposed European supply chain law also only applies to large companies. Nevertheless, the EC guidelines will, indirectly, create additional obligations for SMEs. These enterprises, being contractors of companies obliged to report, must provide them with more and more information in order to demonstrate their CSR activities [

4]. In perspective, it is likely that the reporting requirements will be extended to include small- and medium-sized enterprises.

An example of a regulation that may be disadvantageous for SMEs is the regulation on financing sustainable investments. From 2022, credit institutions must prove the sustainability of their loan portfolios on the basis of the so-called Green Asset Ratio (GAR). Regional banks, traditionally with a high share of SME companies, may find themselves at a competitive disadvantage as their loan portfolios contain a large share of so-called ‘brown’ SME loans not covered by the CSRD. This may cause banks to reduce their provision of ‘brown’ loans, as well as increase the cost of obtaining them [

5,

6]. Information on risk exposures of banks towards companies outside the CSRD that publish the data necessary for the calculation of the GAR will be included in the calculation of the GAR from 2025 onwards, if only the EC gives its approval [

4].

Reporting (mandatory or voluntary) on ESG issues by the majority of enterprises will spread awareness of CSR principles and their implementation, strengthen the EU social market economy, its stability, economic growth, ability to create jobs, and investment, and improve the quality of life in EU countries. Obliging SMEs, explicitly or implicitly, to report ESG requires the introduction of instruments that protect these enterprises from increased administrative costs and ensure that they maintain their competitive position on the market.

This article was written at a time of change for sustainable growth finance and ESG issues reporting. Under the CSRD, from 2023 all companies listed on EU regulated markets will be required to report ESG issues according to standards developed by the EC. This obligation will also apply to a small number of SMEs. Simplified reporting standards are being developed for SMEs. The vast majority of companies operating in the EU are exempted from the obligation to report CSR, and indirectly from this activity. This situation appears to run counter to the European Green Deal (EGD). The EC guidelines allow for the possibility that companies voluntarily prepare reports according to accepted standards. The fact that they do, or do not, report will affect a company’s rating in the financial market. Financing of companies that do not report ESG issues will be considered riskier. Opting out of reporting may become an obstacle to cooperation with companies required to report ESG factors, may damage the company’s competitive position, image, etc.

The article’s contribution to current knowledge in the field of CSR and SMEs is to point out, on the one hand, the changes taking place in the essence of CSR and the consequences of abandoning this activity, and, on the other hand, to point out the benefits achievable from this activity and the methods of proceeding to take advantage of the opportunities arising from the implementation of CSR.

The changes introduced do not prohibit investments that do not comply with the EGD, but they do give a bonus to businesses that follow EU recommendations.

The practical aim of the article is to encourage entrepreneurs to voluntarily engage in the tasks arising from the fulfilment of the constitutional obligation to implement sustainable development.

Method of Doing the Work and Conceptual Model

The starting point of the conducted research is the following research hypothesis: SMEs undertake CSR mainly driven by the benefits obtainable from this activity. The objective of the study was to identify the benefits possible to obtain and the benefits obtained from undertaking CSR in the SME sector.

The paper is based on studies of scientific literature, legal acts, and results of empirical research. The result of the literature studies was the identification of the obtainable benefits from undertaking socially responsible activities by companies in the SME sector. These analyses provided a reference base for the established empirical research results on the benefits of SMEs derived from CSR activities. The empirical research was performed, according to the expert method, in three stages: (1) selection of experts, (2) collection of information by CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interview) and CATI (Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing), (3) development and interpretation of research results in the context of the research hypothesis and the research objective.

Survey participants (experts) were selected with the help of board members of three SME organizations: (a) Northern Chamber of Commerce in Szczecin, (b) Chamber of Industry and Commerce in Koszalin, (c) Catholic Association of Entrepreneurs and Employers in Szczecin. The criterion for the selection of experts was their experience in CSR activities and their personal interest in the results of these activities. These conditions are met by the owners who manage their businesses.

The research was conducted in March and April 2022. Questionnaires were sent electronically by the three organizations mentioned. The experts’ task was to answer (YES or NO) the 28 questions formulated in the survey. The questions and answers are included in

Section 3 of the paper. Since only 24 owners responded to the questionnaire sent electronically (CAWI method), an additional CATI method was used. During the telephone conversations, the questions included in the survey were asked. Experts were encouraged to provide comments and formulate their own assessments of CSR.

The application of this method made it possible to extend the scope of the research conducted beyond the questions included in the questionnaire. In total, in the research conducted using both methods, responses were obtained from 130 experts. The results of the research allowed positive verification of the adopted research hypothesis and to achieve the research objective.

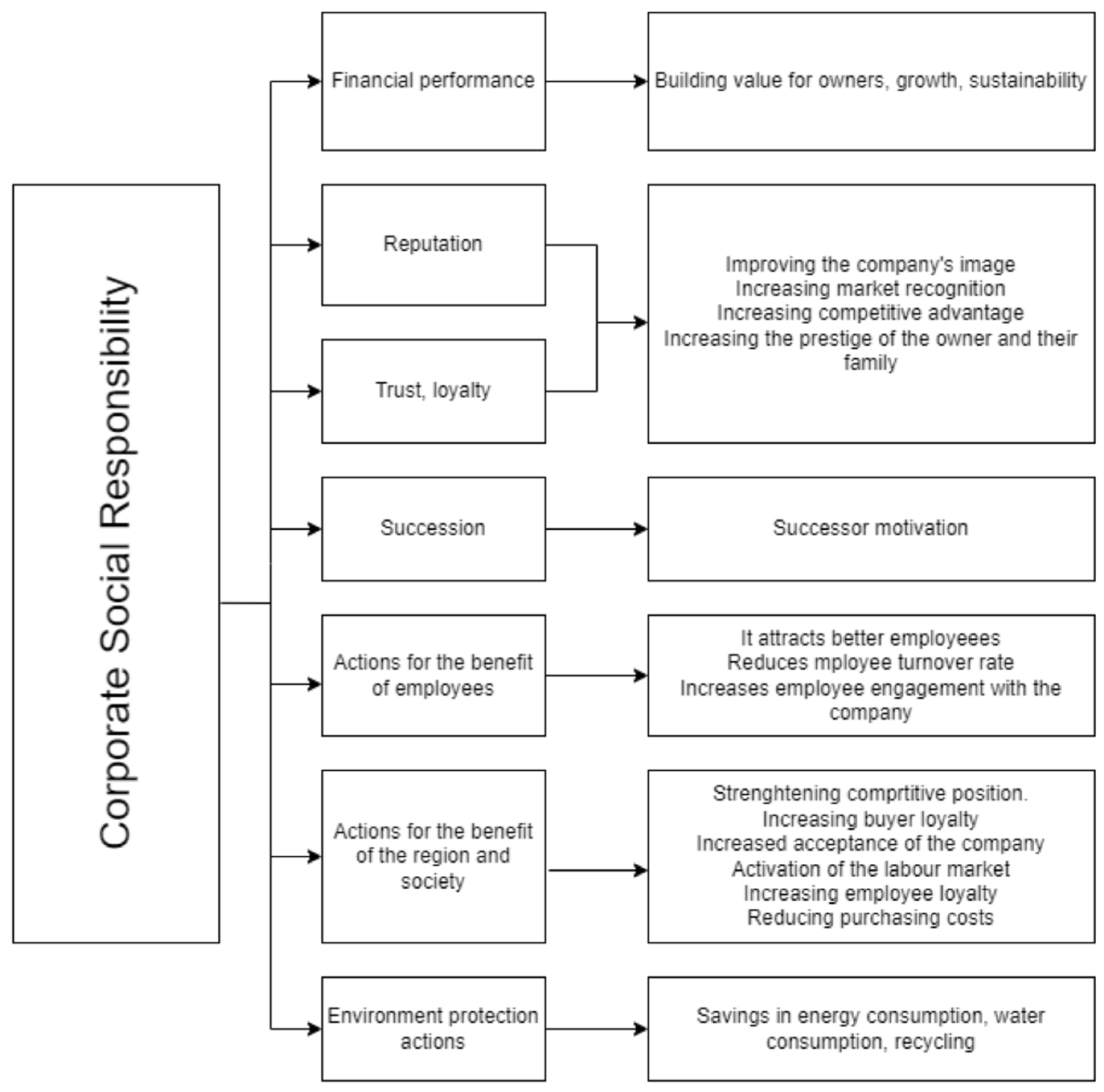

The research makes a conceptual and empirical contribution to the knowledge of the benefits obtained by SMEs from socially responsible activities, and additionally allows to establish the degree of awareness of CSR principles among research participants and factors limiting the application of CSR in micro, small and medium enterprises. The conceptual model for the study is shown in

Figure 1.

Taking into account the rules of reporting CSR/ESG factors currently introduced in the EU, it can be assumed that this article will inspire further, in-depth research on the rationale and consequences of undertaking corporate social responsibility in the SME sector, based on data included in ESG reports.

The article consists of five sections. After a brief introduction, literature review, the study results, discussion, and conclusion are presented.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Modern Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

The concepts of CSR responsibility and sustainable development should be considered with regard to their interrelationships and dependencies. The ISO 26000 standard contains explicit criteria separating these concepts [

2]. According to the Brundtland Report, sustainable development is a doctrine of political economics, which assumes striving for quality of life at the level which the current development of civilization allows, i.e., at a level where the needs of the current generation can be met without diminishing the chances of future generations to satisfy their needs [

7]. The idea of sustainable development is very capacious; it assumes that humanity, and in particular entrepreneurs, should take into account social, environmental, and economic challenges in the course of their activities.

Acting for sustainable development is a principle enshrined in the Constitution, while social responsibility (CSR) is a recommendation for actions for enterprises. By definition, CSR is not any form of certification or mandatory regulation. CSR is the organization’s responsibility for the impact of its decisions and activities (products, services, processes) on society and the environment through transparent and ethical behavior [

7]. Social responsibility is a way of implementing tasks resulting from the commitment to sustainable development adopted in the Constitution. The adoption of CSR principles in the strategy of enterprises is decisive for the fact that the country fulfils the obligation to implement the principle of sustainable development. However, it requires the development and inclusion in the enterprise strategy of a set of ethical, legal, and socio-economic actions that constitute the enterprise’s response to society’s expectations towards the business organization operating on its territory. Socially responsible companies voluntarily invest in human resources, environmental protection, and good relations with the company’s stakeholders and report on these activities, which contributes to improving the company’s image, expanding its sales market, increasing competitiveness, and shaping the conditions for sustainable development. According to experts, sustainable development can be called the mission statement of 2021 [

8].

The idea of CSR is not a new concept. A large percentage of SMEs, even without knowing the name, have long been undertaking activities that could be called ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ [

9,

10]. What is new is the growing interest in CSR from different stakeholder groups: customers, employees, contractors, local authorities, financial intermediaries, capital markets, European Commission (EC). In recent years, interest in CSR has clearly increased not only in organizations but also in public awareness. The COVID-19 pandemic has probably further increased this interest. The ongoing pandemic, as well as the increasingly publicized catastrophic vision of the future caused, among other things, by progressive global warming, make the need to reformulate economic development objectives an imperative of our time [

11].

Climate change and environmental degradation pose a threat to Europe and the rest of the world. The EC’s retort to this situation is the European Green Deal (EGD) action plan [

12]. The EC has pledged to transform the European Union (EU) into a modern, resource-efficient, and competitive economy. The EGD aims to achieve a decoupling of economic growth from the use of natural resources, so that all regions and all EU citizens participate in a socially just transition towards a sustainable economic system. The EGD also aims to protect, preserve, and enhance the EU’s natural capital and to protect the health and well-being of citizens from environmental risks and negative impacts [

4,

12]. The EGD objectives are particularly important in a situation of socio-economic damage caused by a pandemic, war in Ukraine, high inflation rates, and the need to rebuild a sustainable and equitable socially inclusive economy.

The concept of sustainable development, including the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, is of particular interest to the EC. The result of this interest is a drive to replace the concept of CSR with the more precise expression of ESG. Based on ESG factors, non-financial ratings and assessments of companies are created [

4]. The ESG determination originating from the investor–financial world is gradually becoming an important pillar of development and business strategies of many companies. It should be expected that the coming years will be the time of creating social responsibility strategies, the effects of which can be assessed on the basis of specific figures. This will probably be forced by the transformation of CSR into ESG, recommended by the EC [

4,

12,

13].

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the EU requires directing capital flows towards sustainable investments. As a result, guidelines for banks and investment firms to consider social and environmental ESG factors in the risk assessment of borrowers have emerged. Taxonomy-based financing [

13,

14], as well as the implementation of the CSRD Directive [

4] in financial institutions, will bring about changes in the way socially responsible activities are documented in companies. The time since the announcement of the draft CSRD Directive (April 2021) is a period of getting used to the fact that, in the near future, non-financial data will become equivalent to financial data in the reports of listed companies (from 2023 on the basis of the CSRD Directive). These changes, indirectly, will affect all businesses cooperating with companies required to report ESG.

The attention of investors and listed issuers, more than in previous years, is directed towards non-financial issues. Therefore, in order to meet the requirements of the EC, it will be inevitable to transform the existing recommendations that are the foundation of CSR into figures presented in ESC reports.

The country’s social policy objectives and society’s expectations are closely linked and provide a framework for the social activities of enterprises. Through legislation, the government provides the legal framework within which enterprises implement CSR. According to Article 5 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland (RP), the principle of ‘sustainable development’ is a constitutional principle of the Polish legal order. On the other hand, Article 20 of the Constitution of the RP specifies that the basis of the economic system of the RP is a social market economy [

14]. Both constitutional principles express the social and economic objectives pursued in Poland. Provisions in the Constitution make ‘sustainable development’ the official guiding principle of the Polish government; this is very important in light of the reformulation of the economic development goals and the preference for ecological trends that are the imperative of our times.

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Business Objective

In the available literature, there is no known definition that explicitly recognizes CSR as a business objective. However, many studies indicate that any CSR activity should benefit not only the beneficiaries but also the companies [

1,

5,

9,

10]. CSR has become a complex issue and has generated controversy regarding the legitimacy and scope of its implementation.

When analyzing views on CSR, one sees two main research positions on this issue: opponents and supporters. The starting point of the argumentation critical towards the doctrine of social responsibility is the assumption that economic and social goals are contradictory, and no common areas can be found. This position is most fully revealed in such trends as neo-liberalism and post-modernism. Examples are the views of Friedman [

15] and Karnani [

16]. These authors consider that the only social responsibility of business is to bring profits to owners, and the implementation of this goal is the only task of managers, for which they are responsible to shareholders. The doubts of both authors concern only the social responsibility of companies managed by managers. Both Friedman [

15] and Karnani [

16] point out that the critical assessment of CSR does not apply to enterprises with unity of ownership and management, i.e., owner-managed enterprises. Unity of ownership and management is a distinguishing feature of family-owned (FB) businesses, which account for about 90 percent of enterprises belonging to the SME sector [

9]. An owner-managed business can operate in a socially responsible manner because the owner is only liable to himself (and possibly to employees). However, if owner-managed companies consistently prioritized social goals over economic ones, this could result in reduced profits and funding opportunities for business growth. In seeking to increase profitability, however, the owner must behave in an ethical manner [

15]. A part of society does not accept some business practices, even very profitable ones, if they contradict their values, such as child labor in businesses.

Another argument against CSR is that companies use these activities only to improve their image and distinguish themselves from their competitors, without contributing to sustainable development goals. CSR is used, above all by large companies, as a marketing instrument. Such actions are more and more often criticized and referred to as greenwashing [

17]. Greenwashing practices are fostered by treating CSR as an idea, a recommendation. The obligation to prepare standardized ESG reports and their attestation can effectively counteract such practices.

According to CSR advocates, a company can reconcile economic and social objectives by taking a strategic and methodical approach to CSR and by embedding this activity in its long-term business strategy. The arguments for CSR are based on Rousseau’s Theory of the Social Contract, according to which society, in order not to perish, has entrusted entrepreneurs with large amounts of resources to fulfil their mission; they must therefore manage these resources on behalf of society as its wise trustees [

18]. Crucial to this view of Rousseau is the belief that resources belong to society, and that businesses can only exist because society consents to their use. Society grants such consent with the expectation that enterprises will act in the interests of society. From this, it follows that enterprises share responsibility for the development and welfare of the society in which they operate. Confirmation of entrepreneurs’ awareness of this responsibility can be found in a 2018 letter from Black Rock President and CEO Larry Fink, in which he wrote that society demands that companies, both public and private, serve social purposes. To prosper in the long term, every company must not only deliver financial results, but also demonstrate how it makes a positive contribution to sustainability. Companies must benefit all their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate [

18,

19].

The EC recommends that EU companies pursue social activities and integrate them into long-term development strategies. This is evidenced by the draft CSRD Directive heralding the introduction of an obligation to report ESG issues for all companies listed on regulated EU markets, and a proposal for other companies to report ESG factors on a voluntary basis, according to standards adopted by the EU [

4,

12]. The preparation of standards for reporting ESG factors highlights the new business dimension of CSR and the importance of its dissemination in enterprises. Universal reporting on ESG issues would be in line with the idea of the ISO 26000 Guidance on social responsibility. The creators of this standard recommend the implementation of CSR in all organizations—public, private, and non-profit—regardless of their size and location, operating in developed and developing countries [

2]. Thus, it can be concluded that according to the creators of ISO 26000, a strategic approach to CSR is recommended to all organizations, as well as the reporting of this activity.

Organizations representing SMEs, and most SMEs, oppose the introduction of mandatory CSR reporting, but remain open to the idea of voluntary reporting according to simplified standards approved by the EC [

20].

Many scientific considerations present the view that enterprises, while pursuing their economic goals, can and should engage in solving important social problems [

5,

8,

10,

12]. Porter and Kramer express the view that business success should go hand in hand with benefits for society. This allows the enterprise to generate value significantly greater than profit alone, for example: increased innovation, productivity, competitiveness, diversification of activities, expansion into new markets, etc. These authors also point out that CSR can lead to competitive advantage if it results in new products or innovative business processes. They also argue that limiting CSR to activities consisting only in shaping the image, for example, by sponsoring culture or sport, does not bring as much benefit to either the company or the society as new products manufactured in accordance with the expectations of stakeholders [

21].

Changing views on the role of CSR also causes a shift from the paradigm of social responsibility understood as ‘doing good for the sake of doing good’, to the paradigm of ‘doing good for mutual benefit’. In the earlier approach, CSR was limited to charitable activities, enterprises acting as so-called ‘good citizens’, who gave support to good causes, not expecting any benefits in return. Such an approach, popular in the 1960s and 1970s, now has many critics [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

However, the suggestion that businesses should contribute to improving the quality and living conditions of society must be made concretized. The suggestion includes ‘sustainable development’ objectives as a task for government. Enterprises, on the other hand, must pursue economic objectives. Profitability is a prerequisite for a company to engage socially. Drucker emphasizes that solving social problems is the task of government, and the function of enterprises is to satisfy social demand for products and services while benefiting themselves [

26]. Social engagement, in some circumstances, represents the assumption by private companies of government responsibilities, which may be at the expense of the development of these companies. It can also be risky for beneficiaries if private companies withdraw from this activity.

According to the second stream of research, CSR is treated as a social investment, which is expected to have business-like benefits [

10,

21,

25,

26]. When investing their funds, companies should finance tasks that bring the best results for society and for the enterprise. Such an expectation is particularly important today in the situation of social and economic crisis. The difficult economic situation means that the financial opportunities for companies to engage in ESG are limited. It is not easy to accurately measure the effectiveness of the impact of social activities on social challenges [

24,

26]. It is to be expected that the development of European Reporting Standards by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) in a simplified form for small and medium-sized enterprises and their issuance by the EC will make it easier for enterprises to measure the effects of their social activities.

Increasing requirements formulated by contracting parties become an important motivating factor for undertaking CSR. The results of the conducted research indicate that contractors obliged to report their activities not only set requirements, but also help SMEs to meet them. This task is carried out as part of ‘fair operating practices’ [

20].

Husted and Salazar argue that CSR initiatives chosen and implemented strategically rather than altruistically have a greater social impact [

27,

28]. Also, Porter and Kramer recommend a strategic approach to CSR, which aims to create a unique proposal for stakeholders and differentiate from competitors by lowering costs or better meeting customer needs [

21]. New CSR guidelines aimed at listed companies will also indirectly affect SMEs [

4,

12]. Pandemics, the war in Ukraine, supply problems, climate change, digitalization—all these challenges are currently creating increased uncertainty for SMEs. In the short term, financial policies for SMEs can mitigate the risks that threaten the existence of individual firms. However, from the perspective of the necessary long-term transformation towards a sustainable, climate-neutral economy, a systemic approach and the development of framework conditions for the entire SME sector is preferable. These businesses, which make up more than 90% of the total number of enterprises operating in the EU, are not only the backbone of the economy, but also make an important contribution to the development of societies and democracies in individual countries. They should therefore also make an appropriate contribution to achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal.

There is certainly no company in which financial data plays a lesser role than non-financial data, which is understandable from an economic point of view. However, this does not change the fact that CSR/ESG issues are increasingly drawing the attention of investors and listed companies. Although only 2024 will be a breakthrough year, when the importance of financial and non-financial data will be balanced on the basis of the EU CSRD, the current trend for 2022 already indicates that including ESG issues in business strategy is not a momentary trend, but an inevitable compulsion. Companies must be preparing to develop a strategy towards a sustainable transformation, as well as to report on ESG factors. Environmental responsibility and climate protection will have an increasing priority not only because of regulations, but above all because of growing risks. In addition to climate neutrality, biodiversity conservation is another issue that urgently needs to be addressed [

29].

A particular challenge for the economic policy of the EC and the individual EU countries is to create framework conditions so that a sustainable, biodiverse, climate-neutral economy can be created by all businesses, including those in the SME sector, while at the same time ensuring that businesses are not overburdened with administrative work and reporting costs that would limit their opportunities for growth.

2.3. Characteristics of Micro-, Small-, and Medium Enterprises That Determine Their Socially Responsible Activity

SMEs defined according to the criterion recommended by the EC [

30] account for 90 percent of all enterprises in the EU. Two-thirds of all private sector employees work in SMEs and contribute more than 50 percent of the value added in EU industry. Twenty-three million European enterprises employ 136 million workers generating GDP worth €6.86 billion [

31]. In Poland in 2019, according to the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP), there were 2.2 million active enterprises, of which SMEs accounted for more than 99.8 percent of all registered enterprises and employed 10 million people [

32]. In quantitative terms, the Polish economy is dominated by small family businesses [

9,

33].

If the EGD scheme is to reformulate economic development objectives in EU countries, it cannot be done without the participation of SMEs, as this would be contrary to the EC’s desire to involve all citizens and organizations in the transformation of the EU economy. The contribution of SMEs to the transformation of the economy should be proportional to their capabilities.

A report published by the Responsible Business Forum confirmed the involvement of SMEs in the implementation of CSR. Many companies have implemented new CSR activities: there has been an increase of 80% of new CSR activities in the area of consumer issues, 65% in fair operating practices, and 40% in activities in the area of employment [

34]. Entrepreneurs showed particularly strong social commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic. They generally tried to ensure the functioning of their businesses using methods other than laying off employees [

9,

34].

Responsibility towards society, including the company’s employees, and a strong connection with the region in which they operate are particular values of the SME sector reducing the uncertainty of the company’s stakeholders during the socio-economic crisis [

35]. Part of the society rewarded this commitment by standing in solidarity with SMEs. In order to support cultural institutions, local shops, restaurants, or gyms, the population used online services for which a fee was charged, signed up for delivery services of catering companies, waived legal claims for reimbursement, chose products of Polish producers and used services of companies with Polish capital.

SMEs are exposed to increasingly fierce competition as a result of increasing imports of goods as well as direct foreign investments. Therefore, it is necessary to undertake activities aiming at searching for new forms of activity, new offer, new markets, new receivers, which in turn require new inspirations and engaging funds to finance these activities. As SME often do not have at their disposal appropriate financial resources, they lose in confrontation with large companies, especially since, due to their modest size, they have fewer possibilities to influence both suppliers and potential recipients. Therefore, it seems important to pay attention to the development of networks of cooperative relations both between small enterprises and between small and large companies [

34,

36].

Distinguishing features of SMEs that predispose them to the implementation of CSR and advantages of SMEs should be indicated, which may facilitate their competition and conquest of new markets. Such SME advantages may include privileged conditions for obtaining support from the Polish government and the EC, knowledge of market expectations and possibility to react quickly to changing market needs, simplified management structures, entrepreneurship and innovativeness, and striving to preserve the enterprise for future generations. A source of inspiration in searching for new ideas may be close relations with employees, local community, perceiving and using development opportunities existing in the region, regional traditions.

For Poland, but also for other countries, a difficult time is coming to repair the damage caused by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, and this repair will take many years. However, it should not be a ‘simple restoration’ of lost capacity, but a restoration of capacity in line with ESG.

These challenges are particularly relevant in Poland and other countries neighboring Ukraine in view of the inflow of several million refugees from Ukraine, mainly women and children. A special feature of SMEs is their distribution throughout the country, not only in the most industrialized areas. Therefore, new jobs in these enterprises can be created in different regions of the country. By creating new jobs, these enterprises can contribute to economic recovery in regions where there was previously a shortage of ‘manpower to work’. In the literature on entrepreneurship, SMEs are seen as having a positive impact on the labor market [

35].

Regional Anchoring of SMEs

The SME sector is first and foremost a ‘local player’, taking into account the interests of the local society, enterprises, institutions, and region in their activities, thus contributing to the implementation of the CSR idea in practice. The local character of SMEs allows stakeholders to distinguish between real environmental activities of these enterprises over ‘greenwashing’. The local market is the place of supply and the market for most SMEs. The employees of SMEs also come from the local market. SMEs are therefore a factor in activating the community and economy of small towns and villages. The specificity of SMEs makes employment in these companies more stable than in large companies [

33].

SME operating on the local market are able to notice new development opportunities and new sales directions, which increases their competitive opportunities. Acting on the regional market of supplies and sales, they reduce their warehousing, transport, and general costs [

37]. In Poland, SME business relations are often based on trust, informal contacts, long-term and regional partnership [

38]. Access to both tangible and intangible regional factors influences the activity and development of SMEs, as well as their participation in the labor market and involvement in solving local community problems. Intangible factors include informal institutions (social attitudes and traditions) and social resources, which are capable of delivering greater value than tangible assets [

39]. Differences in regional innovation are perceived as the influence of entrepreneurial traditions cultivated by FB [

37].

The importance of FB is not only its numerical share in the structure of businesses, but also its inspirational factor in the process of modernizing the economy. Relationships based on family ties provide a stable foundation on which most of the established enterprises are still based. The FBs are organizations focused more on the ‘permanence’ of existence than on profit [

33]. This creates in these firms a unique opportunity for innovative projects and product ideas that require a long time of preparation and implementation. A traditional family with innovative products and services increases the competitive advantage of FB. According to Zellweger and Fueglistaller, the FBs are predisposed to become champions of innovation. The combination of innovation and tradition in FB is the competitive strategy of these companies. FBs, thanks to their long-standing and sometimes multi-generational entrepreneurial culture, are able to adapt tradition in the modern enterprise. On the other hand, many FBs cultivate an entrepreneurial culture that is employee-friendly. This culture is often expressed in two principles: (1) employees are allowed to make mistakes without fear of immediate dismissal and (2) employees are encouraged to interact in the entrepreneurial field [

22].

Studies show that regions with a higher proportion and density of FBs are generally more innovative than those regions with only a few SMEs [

40]. Equally important for SMEs is the social esteem enjoyed by the owners combined with social resources such as networks and support from the local community. Social contacts, close ties with employees, and access to capital from various regional aid schemes partially compensate for the disadvantages of a company’s peripheral location [

41].

It might seem that the globalization of competition will reduce the importance of domestic demand. In practice, however, the nature of the domestic market tends to have a strong influence on how firms perceive, interpret, and respond to buyers’ needs. Indeed, countries gain a competitive advantage in industries where domestic demand gives their firms an earlier signal of emerging buyer needs and where demanding buyers put pressure on firms to innovate faster and achieve more sophisticated competitive advantages than their foreign rivals. Local buyers can help companies gain an advantage if their needs provide ‘early warning indicators’ of global market trends. This happens when a country exports both its values, services, and products [

42].

In 1989, an environmental and gastronomic organization called Slow Food was founded in Bra, Italy. The guiding idea of this organization is: eat natural, minimally processed, clean, local organic food that is free from insecticides and products that have not been genetically modified. Purchase from local farmers markets, use seasonally available local food. The shorter the distance produce has to travel before it arrives on your plate, the fresher and probably more nutritious it will be. Animal products should come from farms that care about animal welfare. Currently, Slow Food is an international movement with over 80,000 supporters worldwide [

43]. The Slow Food organization has been present in Poland since 4 December 2002.

The nature of the Slow Food concept, which promotes the consumption of local food, makes the idea well-suited to the specificity of regionally established and ‘dispersed’ SMEs throughout the country. The mission of this concept is to protect biodiversity in the world’s food supply, educate society on the importance of fresh taste for health, preserve traditional cooking methods and cultivate the distinctiveness of the culinary culture of individual regions. The realization of this idea is an opportunity for pluralism to strengthen the development of the SME sector and a sustainable economy. It is also an opportunity to involve SMEs in the transformation of the economy under the terms of the EGD.

2.4. Benefits of Undertaking Socially Responsible Activities

CSR as a management approach means changing the relationship between business, society, and the environment. This enables companies to achieve benefits of various kinds. A condition for success is that CSR is a strategically implemented model [

44]. The strategic implementation of CSR makes the question of benefits for the company increasingly important. However, the economic impact of CSR activities is difficult to assess and is contested both in practice and in science [

45].

CSR requires a considerable personal, financial, and intangible effort, which, of course, must be beneficial from the company’s point of view [

46]. The benefits resulting from the implementation of CSR cannot always be expressed in monetary values or only with difficulty. Analyzing the idea of CSR, it is possible to identify 11 benefits possible from this activity:

Improving organizational governance.

Companies that develop and declare CSR—that set out visions and objectives and put them into practice—are seen as more credible. The adopted goals and visions indicate the company’s mission and direction. Shared goals and values, environmentally friendly production methods, and ‘transparent’ business practices unite staff members (employees and managers), and CSR is therefore considered to support enterprise development.

The production of (obligatory or voluntary) standardized CSR/ESG reports can facilitate the transformation towards a socially responsible enterprise, can contribute to cooperation opportunities with large enterprises, and can be an incentive for investors to co-finance the enterprise. These reports can also enable SMEs to cost-effectively communicate information to contracting parties (e.g., financial intermediaries, companies obliged to report ESG) and the public interested in the activities of these companies. According to EC guidelines (EBA/GL/2020/06), companies reporting ESG factors can be classified as so-called green sectors and gain access to cheaper financing. Standards developed for SMEs will also indicate the scope of CSR information that SMEs can request from suppliers and customers in their value chains and—at the same time—the scope of information that can be requested from SMEs by their contracting parties.

The benefits a company obtains from implementing CSR, to a large extent, are determined by the attitude of its employees. That is why it is so important to treat employees fairly. By engaging in CSR, it is possible to increase the motivation of employees, as well as job satisfaction, and increase the willingness to cooperate for the good of the company. Thanks to these interconnections between the company and its employees, CSR has a direct impact on its economic success [

47]. Employees are more willing to work in organizations with a good social reputation and high ethics, where ‘transparent’ behavior is practiced. Confirmation of job satisfaction is a lower employee turnover rate. If employees accept CSR principles, they identify with their work and the company, achieve good results, and behave loyally. This ensures that CSR principles are respected in every work position. Highly competent employees are more likely to be employed by a company with a good reputation, are committed to the company and are often the originators of innovative products and services. A good reputation also results in a larger pool of candidates when the need for additional staff arises. Graduates respond more readily to offers from a reputable company. If employees accept CSR principles, they identify with their work and the company, achieve good results, and behave loyally. This ensures that CSR principles are respected in every work position. Highly competent employees are more likely to be employed by a company with a good reputation, are committed to the company, and are often the originators of innovative products and services. A good reputation also results in a larger pool of candidates when the need for additional staff arises. Graduates respond more readily to offers from a reputable company. Since not only professional competences, but also, to an increasing extent, social competences are regarded as key qualifications in employees, they are particularly valued. Consequently, measures should be taken to promote these skills. Following the CSR concept provides a good opportunity to enhance social competences. The entrepreneurial culture practiced in companies not only influences the productivity of employees but can also affect the way they think and behave in their private lives. This, in turn, has an impact on society and, in the long term, changes social norms and values.

Improving image and reputation. Enhancing a company’s reputation is one of the most frequently cited benefits companies achieve from implementing CSR [

48,

49,

50]. Companies, due to their role in the economy, are increasingly in the center of public attention. The value of a company, to an increasing extent, is determined by non-financial factors: credibility, ethics, reputation, and image. A company that is socially committed in an environment that is informed about it gains a better position in public esteem [

42,

48]. Also, the owners and their families enjoy more prestige in society.

Customer loyalty. Due to the constantly increasing supply in the market, there is strong competitive pressure among manufacturers. Potential customers are well-informed and demanding. They consider the possible alternatives before making a purchase decision. Retention of existing customers is therefore of great importance for companies. As already mentioned, demanding customers can inspire the introduction of new products and services. Winning new customers is much more expensive for a company than retaining existing ones, which is why it is so important to persuade customers to the goods and services offered by the company. In addition, convinced buyers make recommendations and can encourage new customers to buy.

Consumers who are well-informed about CSR seek information that is less price- oriented and more about the company’s environmental and social responsibility. Among CSR issues, consumers value environmental protection, treatment of employees, job security, and compliance with social norms most highly. Reducing the number of jobs, lowering the remuneration of employees below the average, not producing energy-efficient and environmentally friendly products, and not complying with social standards are evaluated critically [

20,

46].

Product differentiation and competitive advantage. For the company’s most valuable customers, in most cases, a simple price/quality ratio is no longer sufficient. Making a purchase decision depends on an additional, convincing argument. This can be, for example, an impeccable reputation or a good corporate image, because in this case, customers know that their money is well-spent. Moreover, such behavior also reflects the customers’ point of view on CSR.

Contact management. If a company takes up the challenge and initiates interesting, effective CSR projects, it will gain a pioneering position. Managers of other companies will learn about it and perhaps express an interest in cooperation. As a result, new contacts may be established and the company’s network of business partners expanded. Of course, advertising campaigns should also be mentioned here as a possible means to an end. In a way, CSR can be compared to sophisticated image campaigns [

46].

Enhancing commitment to sustainable development. The result of social activity is the economic sustainability of the company. The beneficiaries of this sustainability are both the owners of the company and the employees. The owners can expect that the company has an unthreatened future and thus will continue to be a source of their income and personal satisfaction. Matejun points out that the benefits of social engagement are achieved not only by the company, but also by the owner and his family. CSR has an impact on generational continuity in the enterprise (good reputation of the enterprise encourages succession) [

33,

51]. Benefits for employees include unthreatened employment and earnings.

Overcoming public relations crises. Due to their status in society, companies must attach great importance to their credibility, reputation, and image. Even the smallest mistake, shortcoming, or negative information can have an adverse effect on a company’s future. Lin-Hi et al. point out that CSR includes both ‘doing good’ and ‘avoiding evil’. The former concept refers to undertaking social responsibility (‘doing good’) and the latter to avoiding CSR violations (‘avoiding evil’). ‘Doing good’ does not enable per se the avoidance of wrongdoing. However, the need to ‘avoid evil’ should not be underestimated, because a company’s misconduct has a greater impact on its reputation than ‘doing good’. Reputations can be seriously damaged by misconduct, which cannot be easily compensated by social commitment [

50]. Therefore, ‘avoiding evil’ has become an important challenge for companies implementing CSR. Of course, a company should avoid unfavorable events, but if this has already happened, the good reputation that has been built through previous CSR activities can protect against total disaster.

Location and regional development. As already mentioned, this circumstance is of great importance in the case of regionally established companies. The community and the regional environment are the basis of SME operation, and they are also a source of special benefits for the organization, owners, and employees. Regionally established companies show great sensitivity to disturbances in their operating environment, and this can have a direct impact on the internal functioning of the company. Therefore, situations that may cause disturbances in the environment should be avoided.

Transparency in charity. Businesses often face a large inflow of requests for financial support. As they cannot (or do not want to) respond to all of these, they must reject some of them, which can lead to resentment on the part of those rejected. Being transparent with the charity can prevent the company from creating a negative image in such a situation. Doing charity in a systematic way and communicating the principles of charity allows a company to reap the benefits of charity, to be transparent in its implementation, and at the same time, to avoid the ‘reluctance of the rejected’. The principle of transparency may be appealed to by companies that already apply CSR or already do something for the community or for society, and thus already do everything their financial possibilities allow. In such a situation, rejection of a request seems to be easier to accept.

To sum up: the implementation of sustainable development goals brings many benefits to companies. The condition for obtaining possible benefits from social activity is both its implementation in a systemic way and dissemination of information about it [

48]. Customers are willing to pay more for the products of a company with a good social and ethical rating. Also, employees are more willing to work in organizations with a good reputation and high ethics, where ‘transparent’ behavior is practiced.

2.5. Costs of Undertaking Social Responsibility

The presented research mainly focused on benefits, which does not mean that CSR costs should not be indicated. However, these costs are of a specific nature, and their incurrence is most often a voluntary decision of an enterprise. Literature studies indicate that the implementation of social activities in a systemic way enables the transformation of costs incurred in connection with CSR into economic success [

27,

44,

46,

49].

A key challenge for socially engaged enterprises are the costs associated with implementing and executing CSR and measuring and presenting results [

19,

34]. Costs appear at the first moment of implementing CSR strategy in the company. The greatest difficulties arise from the need to adapt the company and employees to CSR requirements. A holistic understanding of social activity encompasses cooperation with suppliers, the production process and provision of services, cooperation with recipients, as well as business management. Thinking in economic, social, and environmental terms should be part of every area of a company’s activities. The implementation of CSR requires that all participants in the supply chain are encouraged to act in the same way and to achieve the same results. The condition for successful implementation of CSR in a company is having all participants interested in achieving the goal of sustainable development [

44,

46,

49].

An important cost factor for companies implementing the social responsibility strategy are operating costs incurred in the production process [

20]. The continuous transition to new, more environmentally friendly technologies generates costs for the company. In the long run, they can be ‘compensated’ by more efficient and/or more economical production, e.g., by using less water or electricity, and therefore investments in CRS, although sometimes costly, contribute to laying the foundations for increased profitability of the business.

CSR reporting is also a large cost, but thanks to this, a company can achieve many benefits, e.g., increased market recognition, improved image, increased trust, lower cost of financing, an offer of cooperation from companies obliged to ESG reporting, etc.

So far, the beneficial effects of the ‘regional grounding’ of SMEs on their social engagement have been presented. In practice, however, negative effects of this entrenchment due to so-called social proximity are also possible [

35]. Social proximity also implies social control and may cause entrepreneurs to feel obliged to engage in social activities and consequently focus less on the real purpose of their business. The results of a study by Bluhm and Geicke confirm that philanthropic motives play a greater role in FB than in other companies [

52]. If ‘forced commitment’ leads to a reduction in revenues and profits, it may also result in a reduction of this commitment in the future. As indicated earlier, maintaining transparency and a systems approach to philanthropy can counteract the occurrence of ‘forced involvement’.

Effective implementation of the CSR strategy also requires proper waste disposal. This entails costs, e.g., for the construction of special facilities and compliance with safe waste disposal procedures. Rational management of natural resources and waste can reduce these costs.

Costs also arise in connection with the creation and strengthening of social relations. These costs include the organization of meetings with partners, activities for employees and their families, participation in local initiatives, etc. The effects of these costs are the already mentioned benefits for the organization, improvement of relations with employees, partners, good reputation, and increased recognition of the company on the market.

Investing in modern, energy-efficient technologies or RES (renewable energy sources) causes costs at the time of investment, but in the future, they can increase the profitability of production. Also, hiring highly qualified employees causes an increase in wage costs, but thanks to their competence, production costs decrease, and the competitiveness of the company is strengthened. The condition is that this activity is carried out in a systematic way, that it is part of the long-term strategy of the company, and that it is compatible with the values and objectives of the company.

4. Discussion

The research results presented evidence—although in exploratory rather than representative fashion—evidence that the discourse on expectations towards ‘social responsibility’ is moving ever closer to micro-, small-, and medium enterprises.

Increasing economic, social, and environmental risks around the world, including in EU countries, create the need for all organizations and societies to be involved as soon as possible in counteracting these adverse phenomena [

8,

12]. A special role is played by enterprises [

2,

7,

11,

12]. In market economies, the structure of enterprises is dominated by micro, small, and medium enterprises. These enterprises have a significant share in the production of gross domestic product and in the creation of jobs. Therefore, an effective transformation of the world economy into a sustainable economy cannot take place without the participation of these enterprises. Research results indicate that the contribution of these companies to sustainable development is less than their potential [

5,

46,

49,

53,

54,

55,

56]. Contributing to the realization of sustainable development requires a high investment in terms of personnel, material, and financial resources; it is clear that this must be beneficial for SMEs. SMEs are not obliged to engage in socially responsible activities. Therefore, it was assumed as a research hypothesis that SMEs undertake CSR guided mainly by the benefits obtainable from this activity. The objective of the study was to identify possible and obtained benefits from undertaking CSR by enterprises in the SME sector. The results of the conducted research confirmed the adopted research hypothesis. They also allowed to achieve the objective of the study.

The research revealed insufficient knowledge of entrepreneurs about the meaning and objectives of CSR and the possible benefits of this activity. The results indicate that entrepreneurs often are unable to identify and appreciate all the achievable benefits of this activity. Similar findings were also reported by other studies [

5,

34,

44,

46,

56,

57]. Insufficient knowledge results in CSR initiatives being selected and implemented sporadically rather than systemically; many existing opportunities are not perceived and used by entrepreneurs.

The starting point for analyzing the benefits of undertaking CSR was a study of participants’ knowledge about the concept of corporate social responsibility.

Research has shown that the share of experts declaring knowledge of the concept, principles and objectives of CSR is higher than the share of those applying these principles in their company. The opposite results were shown by research conducted by Siarkiewicz in 2013: 34 percent of SME representatives confirmed knowledge of the CSR concept, and 66 percent declared taking CSR initiatives [

19]. It can be presumed that these results indicate the insufficient knowledge of some of the surveyed entrepreneurs regarding CSR.

According to the survey, all enterprises have obtained one or more benefits from CSR. The research indicates that many entrepreneurs act intuitively; they do not realize the need and benefits of conducting CSR in a systemic way, that is, in a way that allows them to anticipate all the factors, elements, situations, and other circumstances that may occur. Thinking systemically is seeing the whole; it is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than individual elements. This way of operating makes it possible to integrate the various factors into a productive whole and to see the opportunities that exist, and even to avoid the reluctance of a would-be beneficiary if support is refused.

Among the entrepreneurs surveyed, the majority apply individual CSR instruments. None of the companies surveyed are pursuing all 17 sustainability objectives. Similar findings, concerning 1100 medium-sized industrial enterprises in Germany, were also shown by research conducted by IfM-Bonn [

45]. The sporadic, haphazard way of implementing CSR deprives the company of many obtainable benefits and is also inefficient from the social point of view [

42,

44,

48].

It is typical for small companies to implement CSR occasionally, without any link to business strategy, according to the European SME Observatory. By acting in response to the emerging needs of society, these enterprises are unable to act in a way that brings them noticeable benefits [

53]. The condition for achieving significant benefits from social activities is to make CSR an important part of the company’s main decision-making process and to communicate this to stakeholders [

44,

53].

Also, 62 percent of respondents stated that CSR positively influences their company’s financial performance. Another study conducted in Poland among representatives of large- and medium-sized enterprises found that, in the opinion of 77 percent of respondents, CSR has a positive impact on financial performance [

58]. Studies conducted in Spanish SMEs also confirmed this favorable correlation [

58,

59].

However, 54 percent of respondents recognized that their social activities are compelled by stakeholder groups. This survey result resonates with research conducted by Bird and Wennberg indicating that philanthropic motives play a greater role in FB than in other companies [

41].

The current legal regulations do not oblige SMEs to report on their CSR activities, and there is a lack of official statistical data. As a result, this activity is rarely subject to scientific investigation.

The subject of research on CSR, conducted in various countries and by many researchers, has most often been in the case of larger organizational entities. Analysis of CSR initiatives confirms the fact that this concept is still the domain of large companies. A strategic, long-term approach, combined with non-financial data reporting, is closed within a few hundred entities in Poland [

19,

59]. According to the Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdele (KPMG) report, in Poland in 2020, among the 100 largest companies, the percentage of organizations reporting non-financial data was 77 percent, which is an increase of 18 percentage points compared to the previous edition of the survey in 2017 [

5]. The question arises about the dimension of social responsibility among the remaining companies, of which small and medium enterprises account for 99.8 percent of companies [

32].

The research has complemented the existing scientific knowledge by showing that the involvement of SMEs in the implementation of CSR depends on the benefits they receive from it. Insufficient knowledge of entrepreneurs in this field and limited funding opportunities for these activities are the most important obstacles to the dissemination of CSR activities in SMEs.

The research found that the proportion of entrepreneurs perceiving benefits from CSR is higher than those claiming that CSR is almost always an ‘irrelevant expense’. The percentage of entrepreneurs who positively assess the impact of CSR on their company’s operations far exceeds the share of companies stating that engaging in CSR has reduced their profits.

In the case of CSR, as in the case of a large part of management concepts, it is difficult to clearly identify the benefits that accrue to the company. In particular, it is difficult to establish causal links between CSR and a company’s economic success [

44,

45]. Benefits sometimes emerge only when the effects of companies’ social and environmental commitment become visible. The results of research indicate that in many cases, the relationship between CSR and unmeasurable effects of this activity, e.g., employee loyalty and customer loyalty, are visible only in specific situations. An example of such situation was the time of COVID-19 pandemic. This time has shown, in many cases, the strong mutual relationship between employers and employees. Employers kept jobs as long as the company’s financial situation permitted, and sometimes supported—with private funds—employees or their family members who found themselves in financial difficulties. Employees agreed to temporary wage reductions in order to save the company. Customers, during the ‘closing of the economy’, showed their loyalty to the company by placing orders with home delivery, using paid Internet services, etc. [

9].

A prerequisite for CSR to be visible to the environment and to benefit the company is to communicate this to stakeholders [

48]. Large companies communicate their activities primarily through the publication of sustainability reports. ESG assumptions and EC guidelines on sustainability reporting allow us to assume that soon the problem of reporting may also become a challenge for SMEs [

4,

12].

The results of research indicate that the most frequent social involvement of SMEs concerns employees, climate and environmental protection, the region in which the company operates, and the local community. Other studies have confirmed that these areas are most often the object of CSR practices [

20,

46,

49]. These practices include applying the principle of reliability in the management of the enterprise and in relations with employees and contractors, training for employees, including employees in establishing operating procedures at their workstations, additional benefits for employees and their families, climate and environmental protection, and cooperation with NGOs, individuals, and institutions from the local community. Two independently conducted studies in Spain on a sample of small- and medium-sized enterprises have shown that CSR activities focused on effective human resource management and customer satisfaction have a particularly positive impact on financial performance [

59,

60].

In the course of research using the CATI method, experts indicated the lack of a unified strategy (this results, among other things, from the already-mentioned intuitive approach to CSR) and insufficient financial resources for conducting this activity as the most important impediments to the adaptation of CSR in SMEs. Similar results were also obtained in other studies [

20,

34].

The importance of limited resources as an impediment to undertaking CSR in SMEs is confirmed, indirectly, by the increased interest in the idea of CSR in response to a one-off grant for this purpose in 2013 [

20].

The draft CSRD Directive presented by the EC introduces a number of significant changes in the area of CSR reporting, not only changing the name of ‘non-financial activity reporting’ to ‘sustainability reporting’, but also introduces reporting obligations for a much greater number of entities. Another change is the preparation of reports in a standardized manner. Reporting according to binding standards is expected to give stakeholders, including investors, access to comparable data on sustainable development, which will also be more reliable thanks to their mandatory verification. It is estimated that the obligation to prepare reports will apply to about 3000 large companies and about 180 small- and medium-sized listed companies in Poland. According to the CSRD, granting credit to a company that fails to present a report will be connected with higher risk, and thus more expensive for the borrower. The lack of a sustainability report may hinder cooperation between SMEs and large companies obliged to report their CSR/ESG activities. Opting out of voluntary reporting of these activities may worsen the competitive position of the enterprise.

It was believed that the presentation in the above paper of the benefits possible to be gained from CSR and the indication of how it is possible to ‘transform the costs of CSR into economic success’ will induce the managers of these enterprises to take a deeper interest in the CSR issue. The popularity of social activity reporting in Poland is still far from the standards adopted worldwide [

34]; nevertheless, it seems that the introduction of changes to the reporting of information on sustainable development will cause this way of informing about social responsibility to become more common in Poland. Enterprises will receive an instrument to effectively inform the public about their social activity, thanks to which their involvement will be noticed by the community, and thus will bring more benefits to the company. Thus, implementation of CSR/ESG and reporting of this activity is recommended to all SMEs.

Recommendations for Directions for Further Research

This article is not without its limitations, which can be used to establish future research directions. The research was conducted on a survey sample of 130 Polish micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. Another limitation is the time-period of the research. This article is based on literature studies and research conducted at the time of the implementation of the new EC regulations on sustainable development, which will soon change the operating conditions for all businesses in the EU. It would be an interesting challenge, for science and practice, to conduct research in different EU countries on how SMEs react to these changed conditions. The research findings presented here may also inspire a number of studies.

I hope that the presented results of the research will encourage further scientific inquiries, which will reduce the shortage of knowledge in the field of social responsibility of SMEs, indicate methods to increase the interest of these enterprises in implementing CSR in the new conditions of financing sustainable investments, and present proposals for economic policy instruments of the state, which will effectively support these enterprises in the implementation of CSR. Perhaps banks, wishing to strengthen their competitive position, will undertake research to determine how to assist SMEs, for example in reporting ESG factors.