A Study on the Impact of Boundary-Spanning Search on the Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

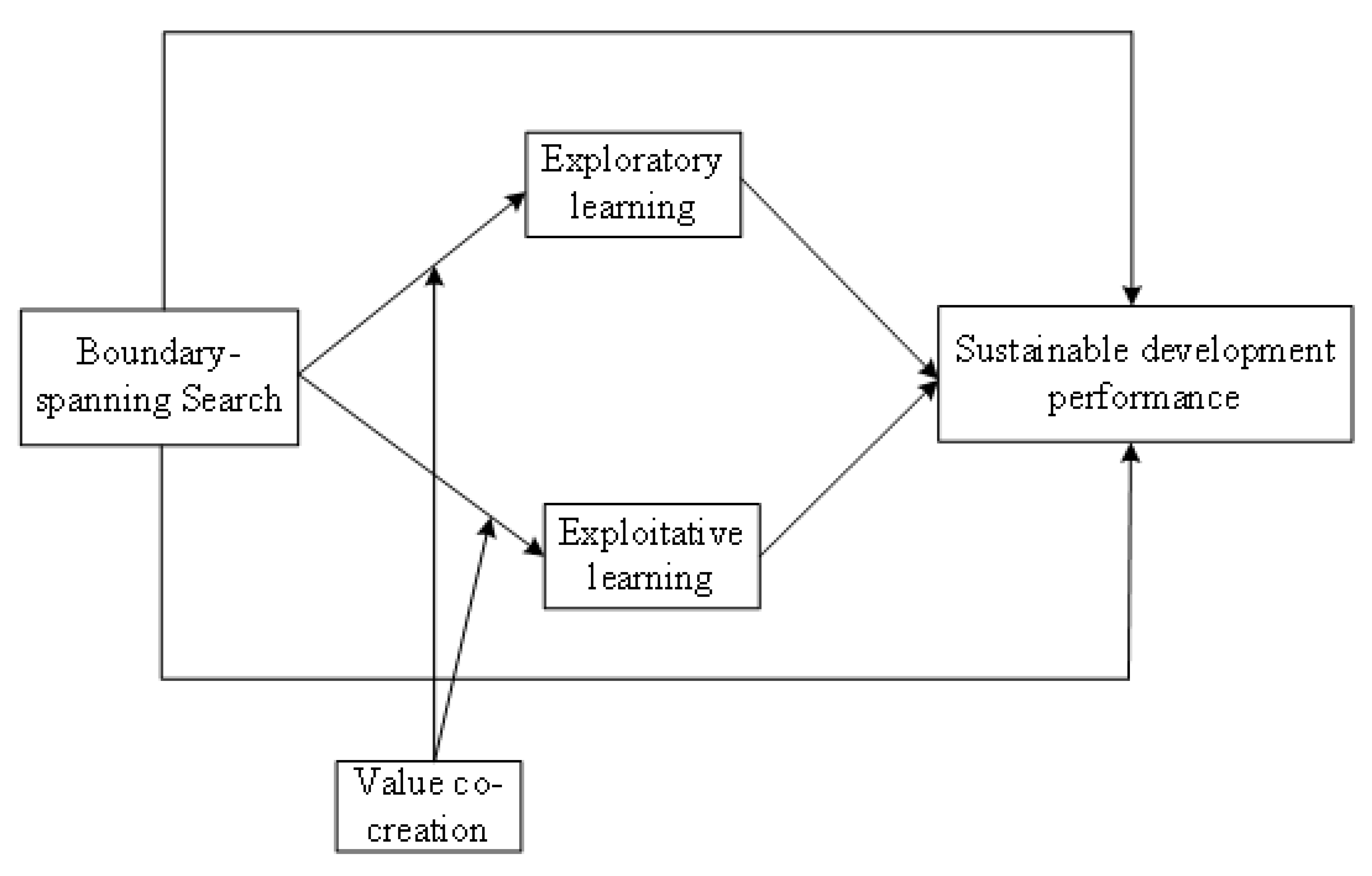

2.2. Boundary-Spanning Search and Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups

2.3. Ambidextrous Learning and Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups

2.4. Boundary-Spanning Search and Ambidextrous Learning

2.5. The Mediating Role of Ambidextrous Learning between Boundary-Spanning Search and Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups

2.6. The Moderating Role of Value Co-Creation between Boundary-Spanning Search and Ambidextrous Learning

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Collection

3.2. Questionnaire Design

- (1)

- Boundary-spanning search mainly draws on the measurement scale of Laursen [9] and others and abridges the original scale to determine the four questions that are most relevant to the implementation of boundary-spanning search strategies of enterprises, such as companies will constantly try new knowledge.

- (2)

- Ambidextrous learning is based on Chung’s [51] scale. The exploratory learning consists of three measures, including questions such as “Companies dare to accept new demands beyond existing products/services”. Exploitative learning is based on four items, such as “Investing resources in the application of existing technologies to improve efficiency”.

- (3)

- Value co-creation is based on the scale developed by Ballantyne [52]. It contains four questions, such as “Customers will discuss our products with friends and family in their lives”.

- (4)

- Sustainable development performance draws on Bansal’s [53] scale, which consists of six questions. For example, “We make many efforts to protect the environment”.

- (5)

- Control variables. Drawing on the findings of previous studies, the age of the firm, firm size, and R&D intensity was effectively controlled [54].

3.3. Reliability Validity Test

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Common Method Deviation Test

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Main Effects Test and Analysis

4.4. Moderating Effect Test

4.5. Moderated Mediating Effects Test

5. Research Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Management Insights

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, W. Knowledge creation through industry chain in resource-based industry: Case study on phosphorus chemical industry chain in western Guizhou of China. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1037–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A.J. The paradox of openness: Appropriability, external search and collaboration. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, K. Innovation types and the search for new ideas at the fuzzy front end: Where to look and how often? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, C.; Sofka, W.; Grimpe, C. Selective search, sectoral patterns, and the impact on product innovation performance. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katila, R.; Ahuja, G. Something old, something new: A longitudinal study of search behavior and new product introduction. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, D. Capability reconfiguration: An analysis of incumbent responses to technological change. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-Y. Applicability of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views under environmental volatility. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Open innovation: Past research, current debates, and future directions. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Fernandez, M.; Pasamar-Reyes, S.; Valle-Cabrera, R. Human capital and human resource management to achieve ambidextrous learning: A structural perspective. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2017, 20, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gummesson, E.; Mele, C. Marketing as value co-creation through network interaction and resource integration. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2010, 4, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.R.; Kaufmann, H.R. Entrepreneurial co-creation: A research vision to be materialised. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 1250–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkopf, L.; Nerkar, A. Beyond local search: Boundary-spanning, exploration, and impact in the optical disk industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.; Love, J.H.; Bonner, K. Firms’ knowledge search and local knowledge externalities in innovation performance. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, C.; Park, J.H. Explorative search for a high-impact innovation: The role of technological status in the global pharmaceutical industry. RD Manag. 2013, 43, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Shin, J.; Hwang, W.-S. Two faces of scientific knowledge in the external technology search process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 133, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, G.; Morris Lampert, C. Entrepreneurship in the large corporation: A longitudinal study of how established firms create breakthrough inventions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, L.; Petruzzelli, A.M. Breadth of external knowledge sourcing and product innovation: The moderating role of strategic human resource practices. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S.; Patel, P.C. In search of process innovations: The role of search depth, search breadth, and the industry environment. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1421–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S.; Ţîrcă, D.M. Innovations for sustainable development: Moving toward a sustainable future. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does it All Add Up? Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, N.; Patton, J. The effects of knowledge-based resources, market orientation and learning orientation on innovation performance: An empirical study of Turkish firms. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 23, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, X. Exploration or exploitation? Small firms’ alliance strategies with large firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y. Ambidextrous organizational learning, environmental munificence and new product performance: Moderating effect of managerial ties in China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Yi, Y.; Guo, H. Organizational learning ambidexterity, strategic flexibility, and new product development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 832–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phene, A.; Fladmoe-Lindquist, K.; Marsh, L. Breakthrough innovations in the US biotechnology industry: The effects of technological space and geographic origin. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, G.; Katila, R. Where do resources come from? The role of idiosyncratic situations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.-R. Determinants of firms’ backward-and forward-looking R&D search behavior. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 609–622. [Google Scholar]

- Flor, M.L.; Cooper, S.Y.; Oltra, M.J. External knowledge search, absorptive capacity and radical innovation in high-technology firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahra, S.A. Organizational learning and entrepreneurship in family firms: Exploring the moderating effect of ownership and cohesion. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Das, T.K.; Teng, B.-S. A resource-based theory of strategic alliances. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, D. Entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework for technology-based enterprise. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2006, 18, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, G.B.; Voss, Z.G. Strategic ambidexterity in small and medium-sized enterprises: Implementing exploration and exploitation in product and market domains. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Noni, I.; Apa, R. The moderating effect of exploitative and exploratory learning on internationalisation–performance relationship in SMEs. J. Int. Entrep. 2015, 13, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyard, J.; Baker, T.; Steffens, P.; Davidsson, P. Bricolage as a path to innovativeness for resource-constrained new firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-J.; Li, C.-R. The effect of boundary-spanning search on breakthrough innovations of new technology ventures. Ind. Innov. 2013, 20, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacklin, F. Management of Convergence in Innovation: Strategies and Capabilities for Value Creation beyond Blurring Industry Boundaries; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, S.W.; Makri, M. Exploration and exploitation innovation processes: The role of organizational slack in R & D intensive firms. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2006, 17, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, M.J.; Tushman, M.L. Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vermeulen, F.; Barkema, H. Learning through acquisitions. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S. Development and return on execution of product innovation capabilities: The role of organizational structure. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, K.; Papalexandris, A.; Papachroni, M.; Ioannou, G. Absorptive capacity, innovation, and financial performance. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütz, F.; Murphy, F.; Mullins, M.; O’Malley, L. Connected automated vehicles and insurance: Analysing future market-structure from a business ecosystem perspective. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; García, J.L.S.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.E. University–industry partnerships for the provision of R&D services. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Maglio, P.P.; Akaka, M.A. On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, M.L. Recombinant growth. Q. J. Econ. 1998, 113, 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.F.; Yang, Z.; Huang, P.-H. How does organizational learning matter in strategic business performance? The contingency role of guanxi networking. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, D.; Varey, R.J. Creating value-in-use through marketing interaction: The exchange logic of relating, communicating and knowing. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, H.; Su, K. Exploring the dual effect of effectuation on new product development speed and quality. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. Humanizing strategy. Long Range Plan. 2021, 54, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Perspectives | Representative Scholars | Define Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Distance Perspective | Rosenkopf & Nerkar (2001) [14] | Boundary-spanning search is derived from remote search, as opposed to local search, which is a search for new knowledge that is far away from the enterprise and in a different field. |

| Resource base perspective | Katila & Ahuja (2002) [5] | Boundary-spanning search is the process of searching for heterogeneous resources to acquire new knowledge, skills, and processes. |

| Organizational Learning Perspective | Roper (2017) [15] | Boundary-spanning search is not only a way to solve problems but also a way for organizations to learn, to learn in the environment, discover new ways to create value, or come up with new solutions to old problems. |

| N= | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Firm age (years) | ||

| ≤3 | 135 | 46.7% |

| 3–8 | 154 | 53.7% |

| Number of employees | ||

| ≤50 | 51 | 17.6% |

| 51–100 | 65 | 22.5% |

| 101–150 | 70 | 24.2% |

| 151–200 | 103 | 35.6% |

| Industries | ||

| New Medicine and Biotechnology | 79 | 27.3% |

| New Energy and Materials | 56 | 19.4% |

| Electronics Information | 43 | 14.9% |

| Precision Instruments | 111 | 38.4% |

| N= | Percentage | N= | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Educational background | ||||

| male | 178 | 61.6% | undergraduate | 19 | 6.6% |

| female | 111 | 38.4% | master | 207 | 71.6% |

| Age | doctor | 63 | 21.8% | ||

| <30 | 20 | 6.9% | Position | ||

| 30–40 | 215 | 74.4% | Chairman | 45 | 15.6% |

| 41–50 | 44 | 15.2% | General manager | 79 | 27.3% |

| >50 | 10 | 3.5% | Senior management | 165 | 57.1% |

| Factors and Items | Loading |

|---|---|

| Boundary-spanning search (Cronbach’s α = 0.892, CR = 0.923, AVE = 0.892) | |

| 1. Companies will constantly try new knowledge | 0.791 |

| 2. Companies are more willing to enter new technology areas on their initiative | 0.953 |

| 3. Companies are committed to seeking new knowledge to break through the limitations of their existing knowledge | 0.9 |

| 4. Enterprises pursue the improvement and perfection of existing technologies | 0.814 |

| Exploratory learning (Cronbach’s α = 0.722, CR = 0.817, AVE = 0.774) | |

| 1. Companies dare to accept new demands beyond existing products/services | 0.95 |

| 2. Companies are often trying to develop and develop completely new products/services | 0.746 |

| 3. From time to time, companies will take advantage of new opportunities in new markets | 0.6 |

| Exploitative learning (Cronbach’s α = 0.93, CR = 0.941, AVE = 0.898) | |

| 1. Investing resources in the application of existing technologies to improve efficiency | 0.821 |

| 2. Ability to incrementally improve and resolve existing customer issues | 0.93 |

| 3. Consolidate development process skills for existing products | 0.895 |

| 4. Frequently adjust procedures, rules, and policies to improve company operations | 0.933 |

| Value co-creation (Cronbach’s α = 0.75, CR = 0.81, AVE = 0.732) | |

| 1. Enterprise employees can solve problems for customers | 0.9 |

| 2. Positive interaction and communication between customers and employees | 0.646 |

| 3. Customers will discuss our products with friends and family in their lives | 0.623 |

| 4. Customers will talk about our products with others on other platforms | 0.69 |

| Sustainable development performance (Cronbach’s α = 0.845, CR = 0.875, AVE = 0.736) | |

| 1. We are very concerned about the work related to environmental protection | 0.86 |

| 2. We make many efforts to protect the environment. | 0.739 |

| 3. Enterprises actively undertake environmental projects | 0.673 |

| 4. Companies frequently review relevant environmental performance | 0.714 |

| 5. In the same industry, our company can obtain good economic performance | 0.721 |

| 6. By protecting the environment, our company has gained social recognition | 0.693 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm age | - | |||||||

| Firm size | 0.406 ** | - | ||||||

| R&D intensity | 0.08 | 0.227 ** | - | |||||

| Boundary-spanning search | −0.158 ** | −0.103 | 0.06 | 0.892 | ||||

| Exploratory learning | −0.015 | 0.002 | 0.152 ** | 0.260 ** | 0.774 | |||

| Exploitative learning | −0.038 | −0.018 | 0.176 ** | 0.177 ** | 0.133 * | 0.898 | ||

| Value co-creation | −0.036 | 0.064 | −0.026 | −0.041 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.732 | |

| Sustainable development performance | 0.002 | 0.056 | 0.274 ** | 0.295 ** | 0.531 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.043 | 0.736 |

| Mean | 3.57 | 2.63 | 3.28 | 3.972 | 4.045 | 3.825 | 3.977 | 3.596 |

| SD | 0.719 | 1.057 | 0.772 | 0.53 | 0.517 | 0.341 | 0.653 | 0.672 |

| Variables | Exploratory Learning | Exploitative Learning | Sustainable Development Performance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Firm age | −0.017 | 0.018 | −0.034 | −0.012 | −0.02 | 0.019 | −0.012 | −0.014 | 0.011 | 0.021 |

| Firm size | −0.028 | −0.011 | −0.047 | −0.037 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.015 | 0.01 | 0.026 | 0.025 |

| R&D intensity | 0.16 ** | 0.138 * | 0.19 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.275 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.227 *** |

| Boundary-spanning search | 0.254 *** | 0.161 ** | 0.285 *** | 0.169 ** | 0.263 *** | |||||

| Exploratory learning | 0.501 *** | 0.458 *** | ||||||||

| Exploitative learning | 0.177 ** | 0.134 ** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.025 | 0.087 | 0.036 | 0.061 | 0.075 | 0.154 | 0.32 | 0.106 | 0.346 | 0.171 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.014 | 0.074 | 0.026 | 0.048 | 0.066 | 0.142 | 0.31 | 0.093 | 0.334 | 0.156 |

| F | 2.39 * | 6.747 *** | 3.513 * | 4.594 ** | 7.758 *** | 12.92 *** | 33.419 *** | 8.38 *** | 29.914 *** | 11.661 *** |

| Paths | EFFECT | BOOTSE | BOOTLLCI | BOOTULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boundary-spanning search-exploratory learning-sustainable development performance | 0.148 | 0.04 | 0.075 | 0.23 |

| Boundary-spanning search-exploitative learning-sustainable development performance | 0.028 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.054 |

| Variables | Exploratory Learning | Exploitative Learning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |

| Firm age | −0.017 | 0.016 | −0.034 | −0.01 |

| Firm size | −0.028 | −0.011 | −0.047 | −0.039 |

| R&D intensity | 0.16 ** | 0.14 | 0.19 ** | 0.177 ** |

| Boundary-spanning search | 0.252 *** | 0.162 ** | ||

| Value co-creation | 0.032 | 0.024 | ||

| Boundary-spanning search × value co-creation | 0.13 * | −0.004 | ||

| R2 | 0.025 | 0.104 | 0.036 | 0.061 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.014 | 0.085 | 0.026 | 0.041 |

| F | 2.39 * | 5.483 *** | 3.513 * | 3.073 ** |

| Intermediate Variables | EFFECT | BOOTSE | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory learning | 0.064 | 0.051 | [−0.027, 0.178] |

| 0.150 | 0.040 | [0.078, 0.236] | |

| 0.249 | 0.061 | [0.137, 0.380] | |

| Exploitative learning | 0.132 | 0.137 | [−0.156, 0.040] |

| 0.262 | 0.120 | [0.006, 0.053] | |

| 0.412 | 0.248 | [−0.007, 0.0917] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, D.; Song, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, X. A Study on the Impact of Boundary-Spanning Search on the Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159182

Wang D, Song J, Sun X, Wang X. A Study on the Impact of Boundary-Spanning Search on the Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159182

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Di, Jianfeng Song, Xiumei Sun, and Xueyang Wang. 2022. "A Study on the Impact of Boundary-Spanning Search on the Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159182

APA StyleWang, D., Song, J., Sun, X., & Wang, X. (2022). A Study on the Impact of Boundary-Spanning Search on the Sustainable Development Performance of Technology Start-Ups. Sustainability, 14(15), 9182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159182