Measurement and Evaluation of Convergence of Japan’s Marine Fisheries and Marine Tourism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Industry Convergence Mechanism

- (1)

- Industry nature

- (2)

- Market demand

- (3)

- Resource allocation

- (4)

- Technological progress

4. Evaluation of Market Development Degree of MF and MT

4.1. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Methods

4.3. Data Testing

- Stationarity test

- 2.

- Cointegration test and Granger causality test

- 3.

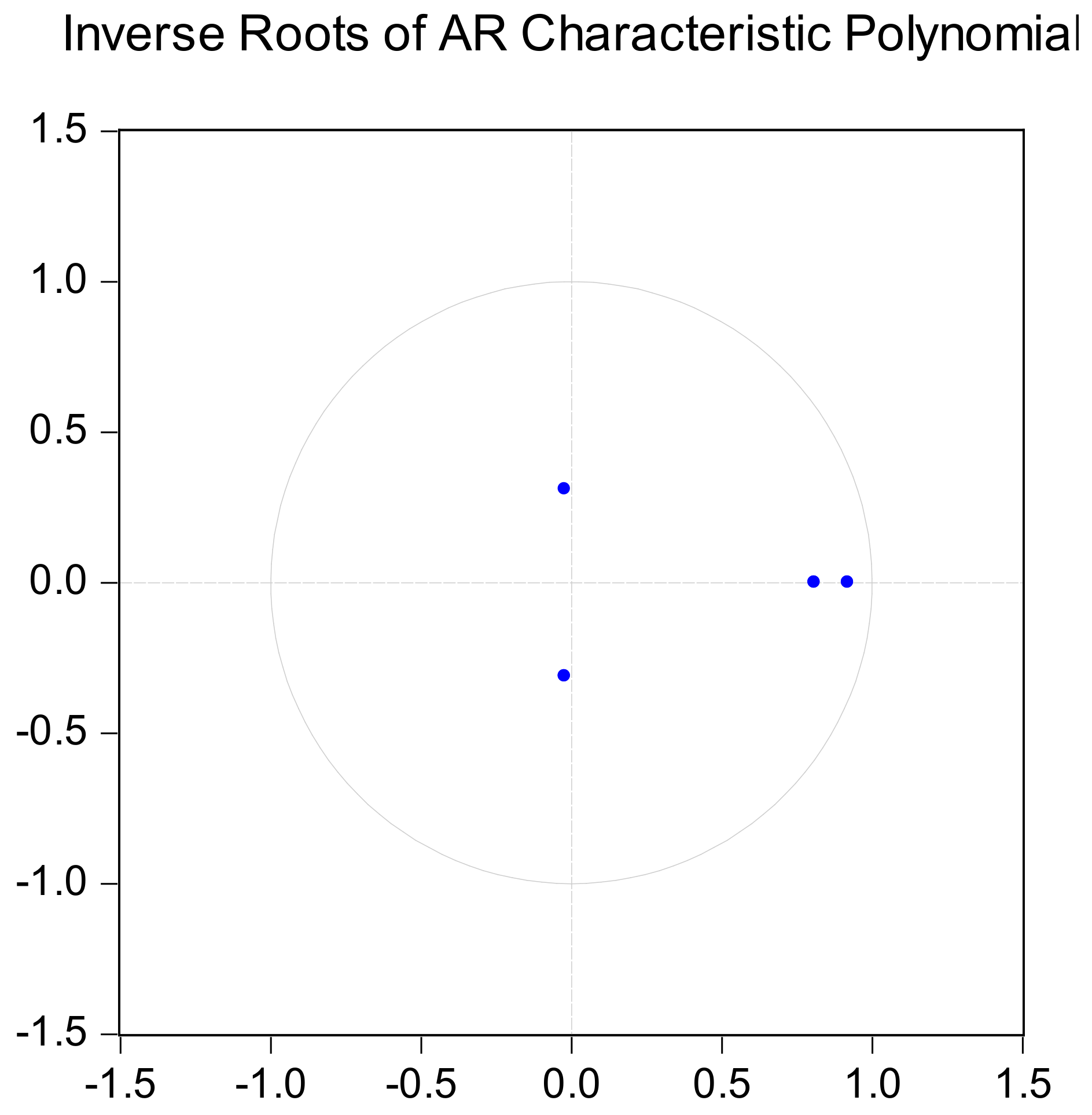

- Stability test for VAR model

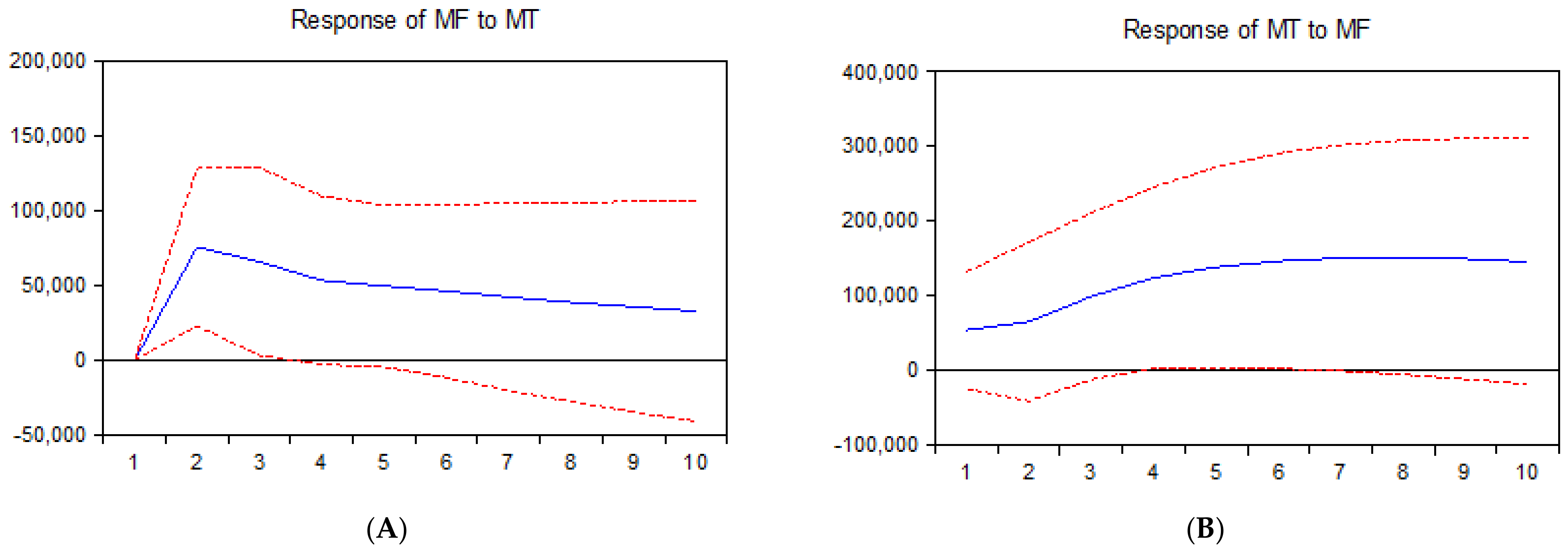

4.4. Impulse Response Analysis

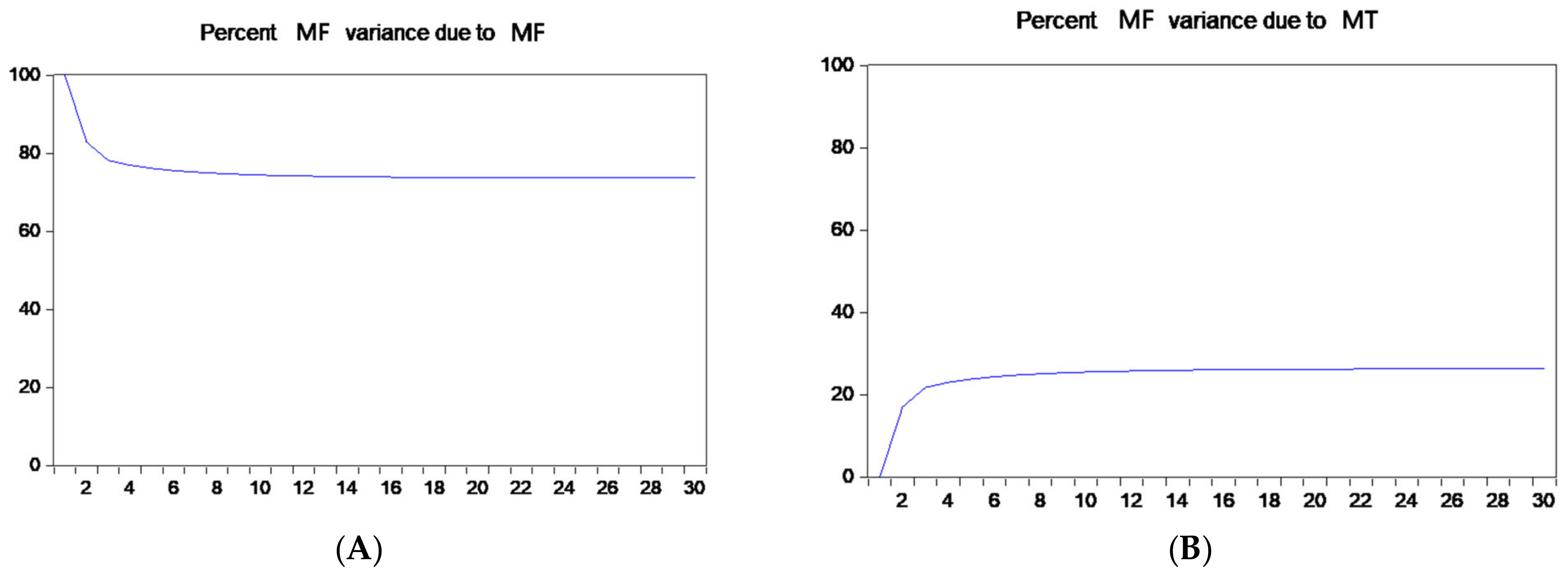

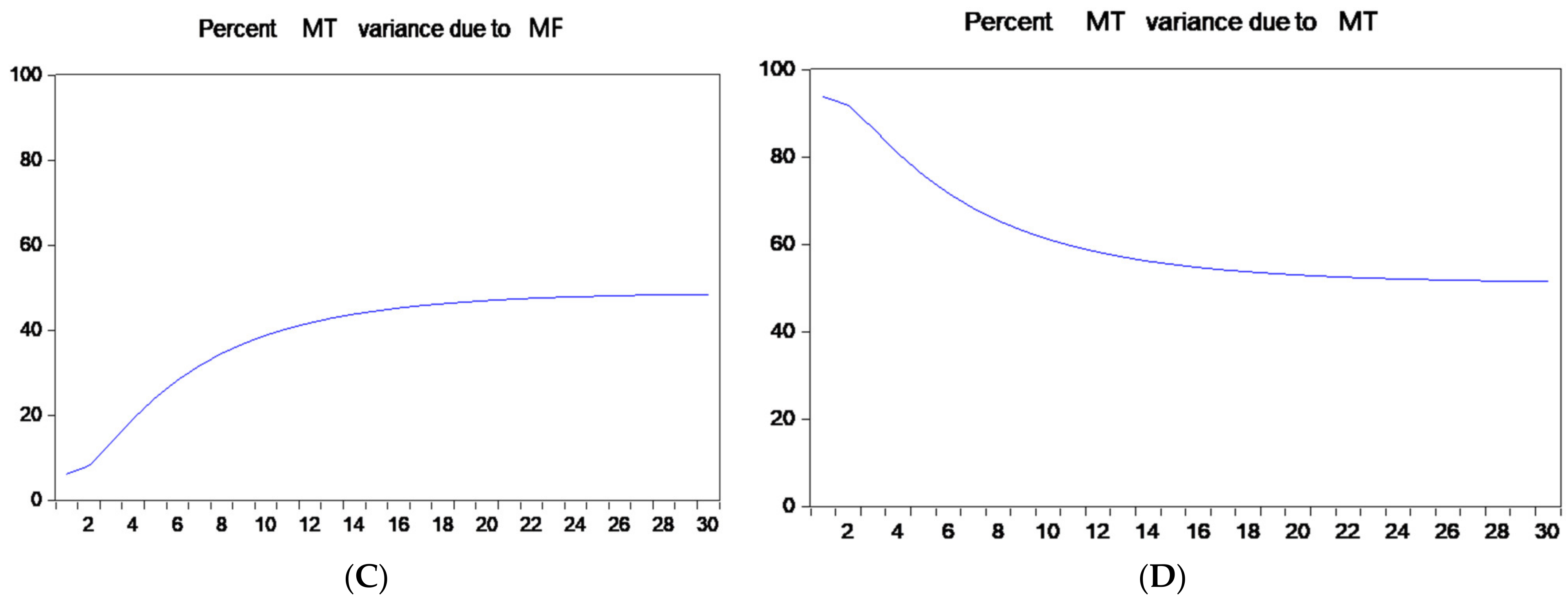

4.5. Variance Decomposition

5. Japan’s MF and MT Integration Model

5.1. Characteristics of Japanese Industrial Convergence

- (1)

- Legal support

- (2)

- Fisheries associations and tourism associations

- (3)

- Financial support

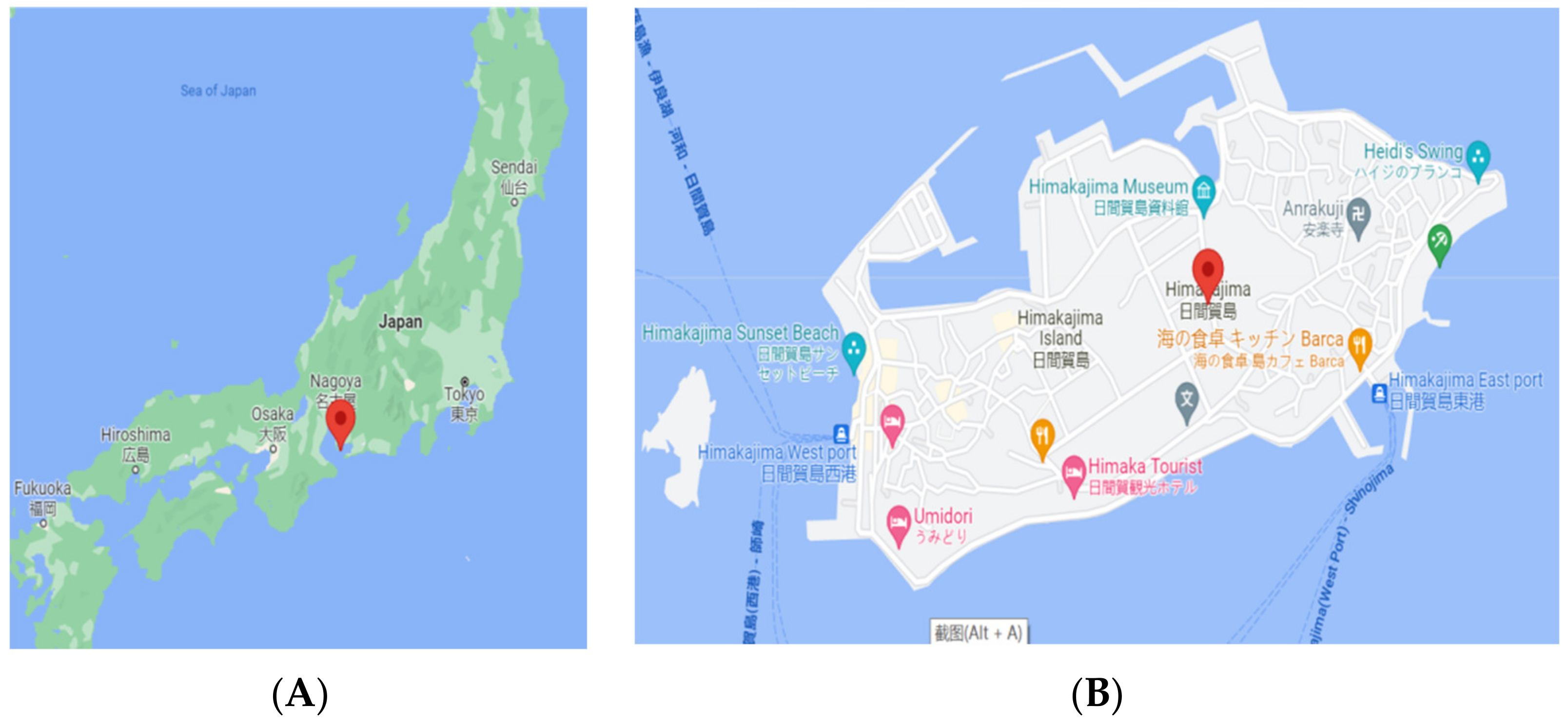

5.2. Industrial Convergence Case Study—Himakajima

- (1)

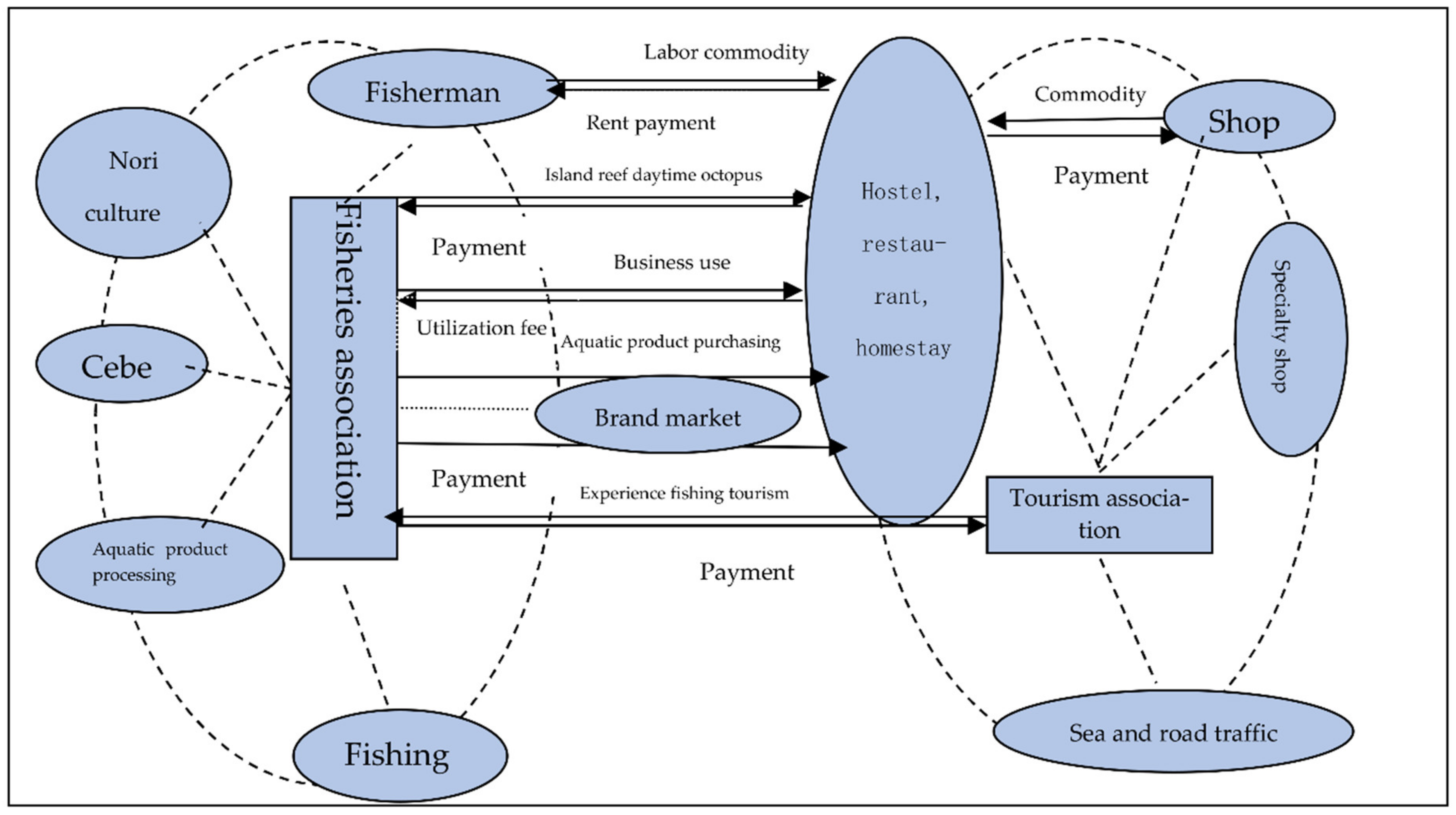

- Integration of products. This type of integration mainly involves tourism practitioners using the local aquatic products caught by fishery practitioners as ingredients in their menu and a transaction relationship between the two industries. Particular emphasis is placed on the cooperation between tourism and fishery professionals in the building of aquatic product brands. Initially, the tourism practitioners proposed the branding of the island’s aquatic products for sale, and the local fishery practitioners actively responded to their idea. The local aquatic product brands play an important role in promoting the tourism industry. Well-known aquatic product brands include “HimaKajima Octopus”, “HimaKajima Pufferfish”, “Island Laver”, and “Pompei Bay”. By building the aquatic product brands in the Japanese production area, the prices of the aquatic products in this area are higher than those of products in other areas in the same period. Well-known aquatic products include “Hikaga octopus” and “Hikashima pufferfish”. The fishery products purchased by fisheries associations are provided to tourism practitioners at a pre-negotiated price throughout the year.

- (2)

- Integration of industrial sectors. The integration of industrial sectors mainly involves the use of the procurement business and credit business of fisheries associations by the tourism industry as quasi-members. This integration can reduce business risks to a certain extent and considerably benefit the tourism industry and fisheries associations. This type of integration is mainly manifested in four aspects: (a) in the process of aquatic product trading and economic cycle within the individual fishery sector and tourism sector, (b) in the labor cycle, (c) in the economic cycle between the fisheries associations and tourism associations, and (d) in the internal circulation of tourism associations. Through the economic cycle of the four aspects, the interest cycle between the economic entities is realized, and the economic benefits of various departments are ensured for subsequent contributions. In recent years, the integration mechanism of Himakajima Island reduced the operational risks of fisheries and tourism while bringing new opportunities to develop the local tourism and fisheries.

- (3)

- Employment integration in the industrial sector. This integration is mainly achieved by employing homemakers from fishers’ homes in the tourism sector. That is, letting the “foreign currency” earned by the tourism industry realize regional circulation through employment and maintain the stability of fishermen’s self-employment. As MF is an industry that targets nature, fishery production is highly susceptible to natural conditions such as weather and seasonal changes, thereby making the livelihood of individual fishermen unstable. By providing work to homemakers from fishers’ homes, the income from the work can be used as a stabilizer for fishermen’s self-employment. In other words, if a sideline income exists, despite the change in the catch, the stability of a fisherman’s business can be ensured to a certain extent. The formation and maintenance of the regional labor market also play a specific role in mitigating the decline and aging of the island’s population.

- (4)

- Cooperation among tourism companies by teaching and popularizing cooking skills through joint cooking lectures; implementing standard menus, standard prices, and daily publicity activities in the region; and determining ways to use island businesses for purchasing food, supporting new entrepreneurs (recommendations for processing and sales and related service industries when opening new stores), and other cooperative and collaborative relationships. Among such measures, “default rules” for purchasing food ingredients exist in the region, which can be considered as an essential economic cycle that formed the current Higashima Island. The core players in this integration are hotels, inns, homestays, and other business operators. When purchasing materials/ingredients for their business, such entities try their best to buy from local stores/providers.

5.3. Impact of Industrial Integration

- (1)

- Reduction of transaction costs

- (2)

- Creation of aquatic product brands

- (3)

- Promotion of social and economic development in fishing areas

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Industrial transformation and upgrading. The transformation and upgrading of MF should be accelerated, and space for fishery development should be vigorously expanded. MT must be developed extensively, and the traditional development model should be improved. The advantages of MT resources should be given full play, the development and management of tourism resources should be improved, and the industrial value chain should be extended.

- (2)

- Industrial integration and development. The industrial linkage between MF and MT is the primary condition for industrial integration. Thus, the scientific and reasonable layout of marine industries and recycling of marine resources are necessary. Investment in marine science and technology should be increased to improve the efficiency of the use of marine resources. In addition, the marine industry chain should be expanded and improved gradually, the marine industry integration mechanism should be innovated, and the integration of MF and MT internal resources, technology, products, and markets should be enhanced. The marine industry development model should be optimized, and new marine industry sectors should be innovated. Furthermore, areas with special conditions should be encouraged to take the traditional fishing culture as their foundation and fishing and ecological aquaculture waters as their landscape, vigorously develop recreational fisheries, and develop in-depth recreational fishery demonstration bases.

- (3)

- Green ecological development. Coastlines and sea areas are the spatial carriers of MF and MT development. The advantages and disadvantages of their environment can determine the sustainability of the development of the two major industries. Maintaining the marine ecological environment, accelerating the construction of marine environments classified as protection or access systems, reasonably controlling the number of marine aquaculture and tourism firms, improving pollution prevention and control capabilities, implementing pollutant discharge assessment and accountability systems for marine-related enterprises, and strengthening management are necessary. Finally, the pollution and destruction of the marine environment should be prevented, and the protection of marine resources should be improved.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ikegawa, Y.; Tobase, T. Estimation of potential oceanic regions and possible CO2 amounts for storage using self-sealing of CO2 hydrate around Japan. J. JSCE 2021, 9, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, Y. Japan’s marine economic development and competition with China. Ccamlr. Sci. 2018, 25, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Karan, P.P. Japan in the 21st Century: Environment, Economy, and Society; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2005; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Henocque, Y. Towards Integrated Coastal and Ocean Policies in France: A Parallel with Japan. In Global Change: Mankind-Marine Environment Interactions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Makino, M.; Matsuda, H.; Sakurai, Y. Expanding fisheries co-management to ecosystem-based management: A case in the Shiretoko World Natural Heritage area, Japan. Mar. Policy 2009, 2, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuroda, H.; Setou, T. Extensive Marine Heatwaves at the Sea Surface in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean in Summer 2021. Remote Sens. 2021, 19, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyano, M. Revitalization of Japan’s Fishing Industry: A Legal Perspective—The Cases of Rishiri and Rebun Islands. In Economic Challenges Facing Japan’s Regional Areas; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, M.J. Globalization and the Historical Evolution of Japanese Fisheries. In Maritime Prehistory of Northeast Asia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tacon, A.G.J.; Metian, M. Fish Matters: Importance of Aquatic Foods in Human Nutrition and Global Food Supply. Rev. Fish Scir. 2013, 1, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.M.; Appel, L.J. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: The Intermap study. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2010, 5, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frankic, A.; Hershner, C. Sustainable aquaculture: Developing the promise of aquaculture. Aquacult. Int. 2003, 6, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigchelaar, M.; Leape, J.; Micheli, F. The vital roles of blue foods in the global food system. Glob. Food Secur. Agric. 2022, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Fishery Output Statistics 1985–2018. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kouhyou/gyogyou_seigaku/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Sakamoto, S. Japan and the Law of the Sea: Key Historical and Contemporary Milestones. In Implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, M.; Hattori, T.; Kariya, M. Comparison of structural changes in the agriculture and fisheries industries before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A case study of Iwate Prefecture’s coastal area. Fish. Sci. 2022, 2, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganseforth, S. Blue revitalization or dispossession? Reform of common resource management in Japanese small-scale fisheries. Geogr. J. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, E.J. Tourism as a Key for Regional Revitalization? A Quantitative Evaluation of Tourism Zone Development in Japan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, Y.; Ichisugi, Y.; Karkour, S. Carbon Footprint Evaluation Based on Tourist Consumption toward Sustainable Tourism in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Survey on National Maritime Awareness 2019. Available online: https://www.nippon-foundation.or.jp/what/projects/uminohi (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Japan Maritime Center. Survey on National Maritime Awareness 2019. Available online: https://www.nippon-foundation.or.jp/app/uploads/2019/07/new_pr_20190708_01.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- The Japan Tourism Country Policy Aims to Make Full Use of the Characteristics of Each Region, Strive to Create Attractive Tourist Spots, Spread the Charm of the Traditions and Cultures of Each Region at Home and Abroad, and Promote International and Domestic Tourism. Systematically Promote Measures Related to the Realization of a Tourism-Oriented State. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/000058546.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Statistics from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/siryou/toukei/in_out.html (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- White Paper on the Oceans and Ocean Policy in Japan. Available online: https://www.spf.org/global-data/20181107105524314.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Department of Marine Strategic Planning and Economy; Ministry of Natural Resources of China. The Statistical Communique of Chinese Marine Economy in 2019. Available online: http://gi.mnr.gov.cn/202005/t20200509_2511614.html (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Rosenberg, N. Technological Change in the Machine Tool Industry, 1840–1910. J. Econ. Hist. 1963, 23, 414–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Industrial Integration: A Literature Review. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2016, 2, 1650007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uekusa. Industrial Convergence of Information and Communication Industry. China Ind. Econ. 2001, 2, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Li, X. Research of industrial evolution and division based on industrial convergence. China Ind. Econ. 2009, 12, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein, S.; Khanna, T. What does industry convergence mean? In Competing in an Age of Digital Convergence; Yoffie, D., Ed.; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1997; p. 2010226. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S. Study on the industrial convergence and enhancing industrial competitiveness. J. Shandong I. Bus. Technol. 2004, 18, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Xia, J. The dynamic mechanism, path, and policy choice of the integration of China’s tourism industry. J. Cap. Univ. Econ. Bus. 2012, 14, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. Research on the Influencing Factors and Spatial Spillover Effects of China’s Regional Tourism Economic Growth—Based on the Spatial Dubin Panel Model. Soft Sci. 2016, 30, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Miret-Pastor, L.; Molina-García, A.; García-Aranda, C.; Herrera-Racionero, P. The connection between recreational fishing and the traditional fishing sector in the emerging area of marine tourism: Challenges and opportunities for diversification with the European Fisheries Fund (EFF). ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2020, 77, 2369–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck, C. Conflicts over Space for Marine Leisure: A Case Study of Recreational Boating in Japan. Curr. Issues Tourc. 2006, 4, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.M.; Bui, T.-D.; Tseng, M.-L.; Lim, M.; Tan, K.; Raymond, R. Sustainable solid-waste management in coastal and marine tourism cities in Vietnam: A hierarchical-level approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Sun, J. Marketing Strategy of Marine Resort: An Exploratory Study. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 106, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L. The Measurement of High-Quality Development Level of Tourism: Based on the Perspective of Industrial Integration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3355. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.J.; Sun, Q.; Gao, Y.; Gao, Y. Resource Integration, Reconfiguration, and Sustainable Competitive Advantages: The Differences between Traditional and Emerging Industries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sick, N.; Brring, S. Exploring the research landscape of convergence from a TIM perspective: A review and research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2022, 175, 121321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lim, S. Convergence Revolution. In Living Innovation; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H. The Impact of Marine Tourism Resources Development on Sustainable Development of Marine Economy. J. Coast. Res. 2021, 94, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.D. Concepts of Digital Economy and Industry 4.0 in Intelligent and information systems. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2021, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2010 Marine Industry Activity Status Survey Report. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/ocean/policies/chousa/pdf/h20san_houkoku.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- 2018 Marine Industry Structure and Scale System Survey Report. Available online: http://fields.canpan.info/report/detail/22489 (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Japan Input-Output Table. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/toukei_toukatsu/data/io/index.htm (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- Sims, C.A. Macroeconomics and Reality. Econometrica 1980, 48, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutkepohl, H. Introduction to Multiple Time Series Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, M.W. Vector autoregressions and cointegration. In Handbook of Econometrics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 2843–2915. [Google Scholar]

- Lutkepohl, H.; Saikkonen, P. Order Selection in Testing for the Cointegrating Rank of a VAR Process. In Cointegration, Causality, and Forecasting; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 68–199. [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner, D.F.; Zha, T. Conditional Forecasts in Dynamic Multivariate Models. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998, 81, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bator, E.T.; Adjieteh, M.A.; Jin, L.C.; Asenso, T.Q. Vector Autoregressive Models for Multivariate Time Series Analysis; Macroeconomic Indicators in Ghana. Math. Theor. Model. 2018, 8, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Juselius, K. The Cointegrated VAR Model: Methodology and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, S. Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 1988, 12, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. Estimation and Hypothesis Testing of Cointegration Vectors in Gaussian Vector Autoregressive Models. Econometrica 1991, 59, 1551–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, Y. Likelihood based inference in cointegrated vector autoregressive models. Economet. Theor. 1998, 14, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, M. Granger causality and path diagrams for multivariate time series. J. Econom. 2007, 2, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterholm, P.; Hjalmarsson, E. Testing for Cointegration Using the Johansen Methodology When Variables are Near-Integrated? IMF Work. Pap. 2007, 141, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H. Unit Roots, Cointegration, and Structural Change. Econ. Rece. 1999, 231, 439–441. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, H.; Shin, Y. Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models. Econ Lett. 1998, 1, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.; Kilian, L.A. Practitioner’s Guide to Lag Order Selection for VAR Impulse Response Analysis. Stud. Nonlinear Dyn. Econom. 2005, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, P.A.; Mittnik, S. Misspecifications in vector autoregressions and their effects on impulse responses and variance decompositions. J. Econom. 1993, 3, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutkepohl, H. Asymptotic Distributions of Impulse Response Functions and Forecast Error Variance Decompositions of Vector Autoregressive Models. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1990, 1, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rural Culture Association Japan. 2013. Available online: https://www.kinokuniya.co.jp/f/dsg-01-9784540092329 (accessed on 2 July 2022).

| Variable | Extent | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Marine Fishes (LR) | Marine Fishes | Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries “Fishery Output Statistics” |

| MT (CT) | Fishing, boat racing, surfing, yachting, skin diving, swimming, tutoring, cruising, canoeing, rafting, fishermen’s inns, and fishermen’s restaurants | “Leisure White Paper,” “Input-Output Table” (1985–2018), and Sixth Industrialization Comprehensive Survey |

| Obs. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 34 | 2,819,604 | 740,176 | 1,845,710 | 3,992,638 |

| CT | 34 | 1,829,882 | 459,499.8 | 1,309,774 | 2,697,635 |

| Obs | ADF | 1% | 5% | 10% | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnY | 30 | –1.645 | –3.716 | –2.986 | –2.624 | 0.4599 | Nonstationary |

| lnX | 30 | 0.001 | –3.716 | –2.986 | –2.624 | 0.9586 | Nonstationary |

| DlnY | 29 | –5.251 | –3.723 | –2.989 | –2.989 | 0.0001 | Stationary |

| DlnX | 29 | –4.944 | –3.723 | –2.989 | –2.989 | 0.0000 | Stationary |

| Hypothesized | Eigenvalue | Trace Statistic | 0.05 Critical Value | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0.338,269 | 1,773,280 | 1,839,771 | 0.0618 |

| At most 1 * | 0.197,817 | 6,171,722 | 3,841,466 | 0.0130 |

| Hypothesized | F-Statistic | Df | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| MT is not a Granger reason for MF | 8.699 | 2 | 0.0129 |

| MF is not a Granger reason for MT | 2.670 | 2 | 0.2632 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Li, P. Measurement and Evaluation of Convergence of Japan’s Marine Fisheries and Marine Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159108

Yao W, Zhang W, Li W, Li P. Measurement and Evaluation of Convergence of Japan’s Marine Fisheries and Marine Tourism. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159108

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Wei, Weikun Zhang, Wenxiu Li, and Penglong Li. 2022. "Measurement and Evaluation of Convergence of Japan’s Marine Fisheries and Marine Tourism" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159108

APA StyleYao, W., Zhang, W., Li, W., & Li, P. (2022). Measurement and Evaluation of Convergence of Japan’s Marine Fisheries and Marine Tourism. Sustainability, 14(15), 9108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159108