The Effects of Innovation Adoption and Social Factors between Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Sustainable Firm Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Review and identify the variables, develop the constructs, and propose the scale for assessing SSCM, SFP and INNO.

- (2)

- Test the scale for validity and reliability.

- (3)

- Investigate the causal effects of SSCM on SFP.

- (4)

- Examine the moderating effects of INNO between SSCM and SFP.

- (5)

- Examine the moderated mediating effects of socio-cultural factors such as age, gender, education, and experience in the causal relationship between SSCM, INNO, and SFP.

2. The Theoretical Background of SSCM, INNO, and SFP

2.1. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices (SSCM)

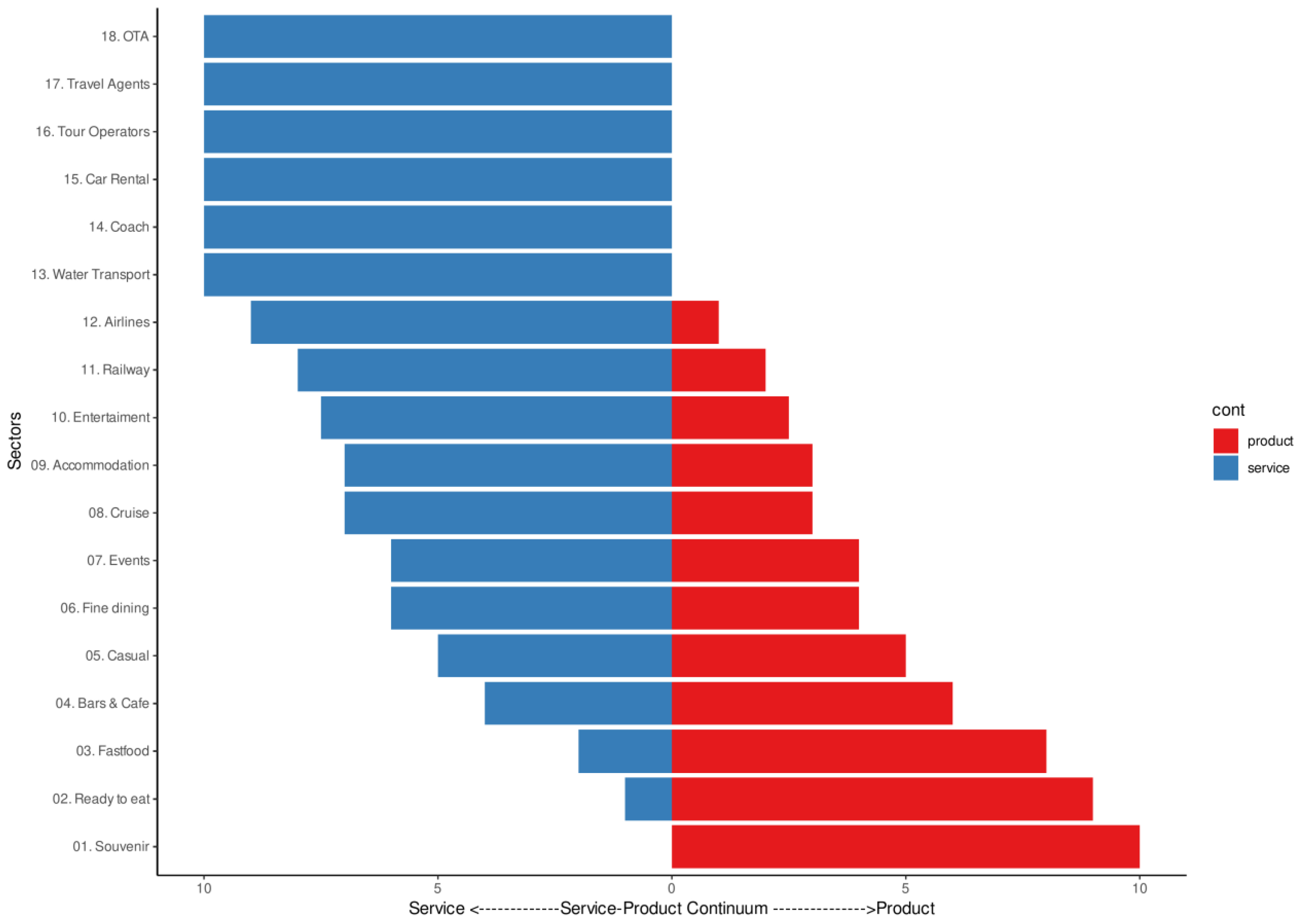

2.1.1. Service–Product Supply Chain Management Practices (SPSSCM)

2.1.2. Service–Setting Supply Chain Management Practices (SSSSCM)

2.1.3. Service–Delivery Supply Chain Management Practices (SDSSCM)

2.2. Sustainable Firm Performance (SFP)

2.2.1. Economic Performance (ECP)

2.2.2. Operational Performance (OPP)

2.2.3. Environmental Performance (ENP)

2.2.4. Socio-Cultural Performance (SCP)

2.3. Innovation Adoption (INNO)

2.3.1. Product- and Process-Based Innovation (PPBI)

2.3.2. Marketing-Based Innovation (MRBI)

2.3.3. Technology-Based Innovation (TLBI)

2.3.4. Organizational Innovation (ORBI)

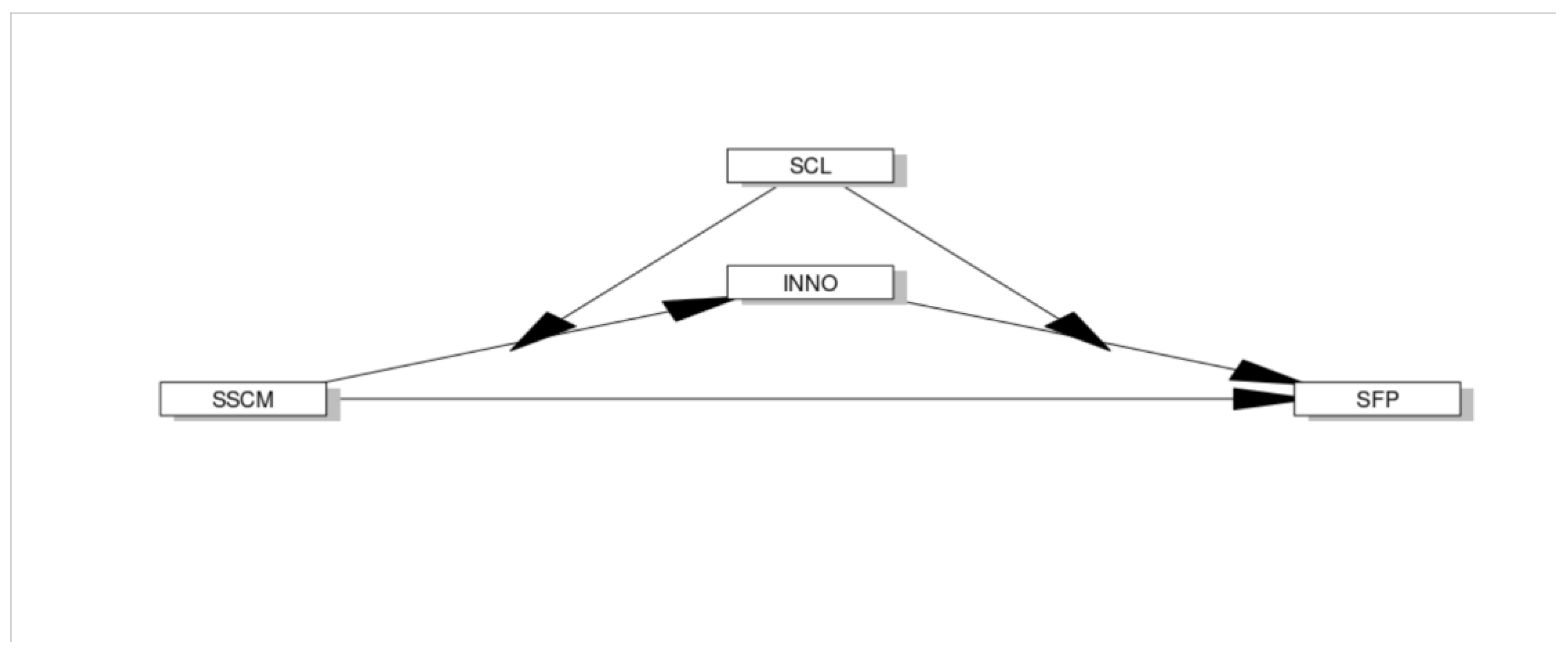

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. SSCM and Sustainable Firm Performance

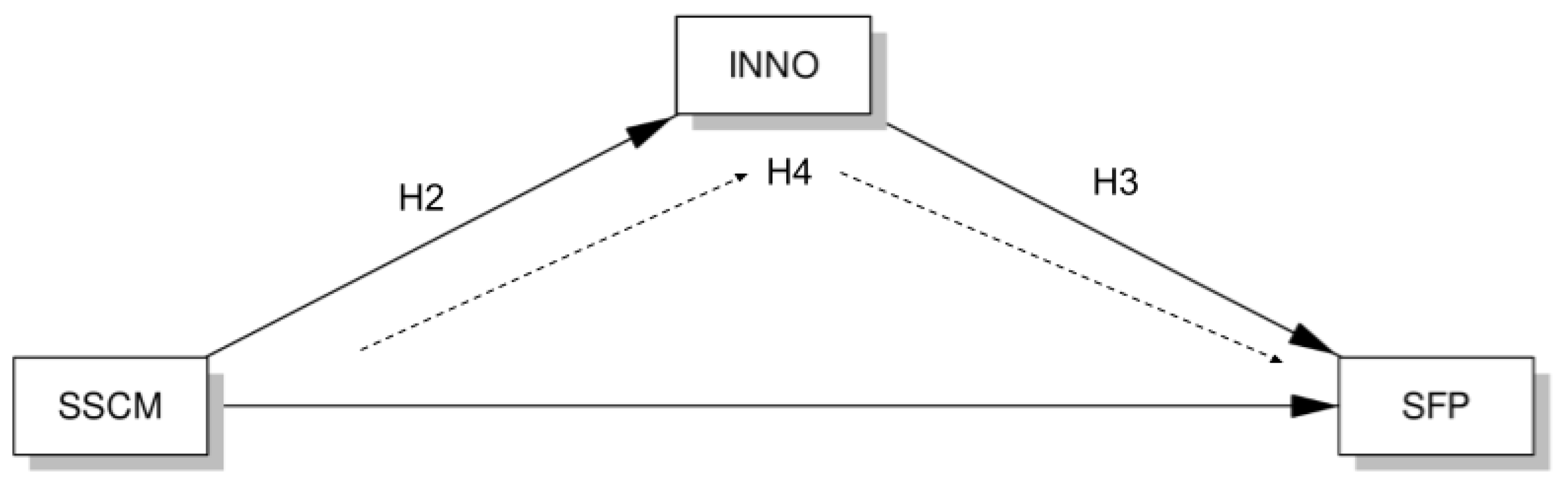

3.2. Mediating Effect of Innovation Adoption

3.3. Moderated Mediation Effects of Socio-Demographic Factors

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Population and Participants

4.2. The Scale and Measures

4.3. Pilot Survey, Content Validity and Face Validity

5. Data Analysis and Interpretation

5.1. Demographic Profile

5.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.2.1. Reliability

5.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.3.1. Model Suitability

5.3.2. Unidimensionality

5.3.3. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices

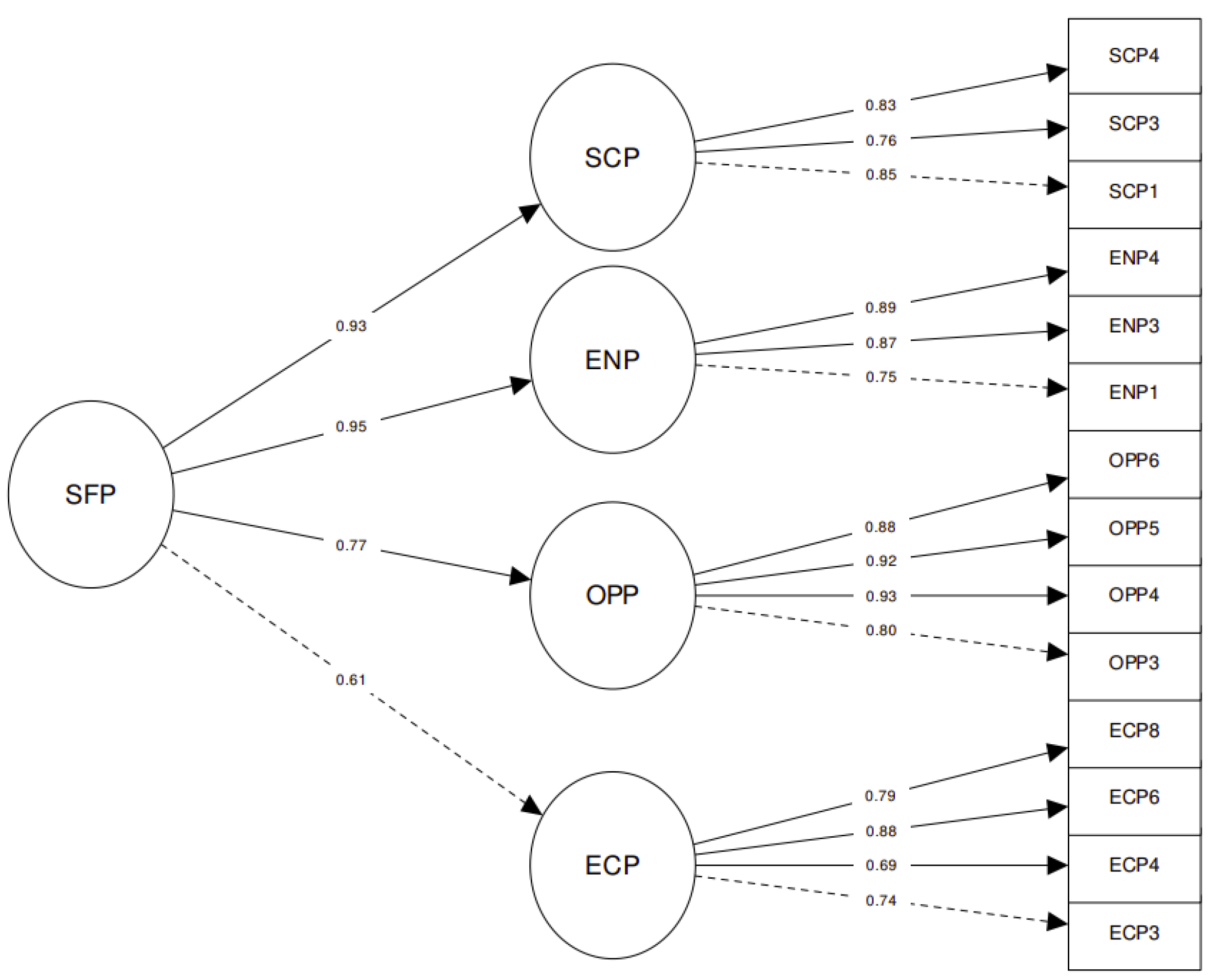

5.3.4. Sustainable Firm Performance

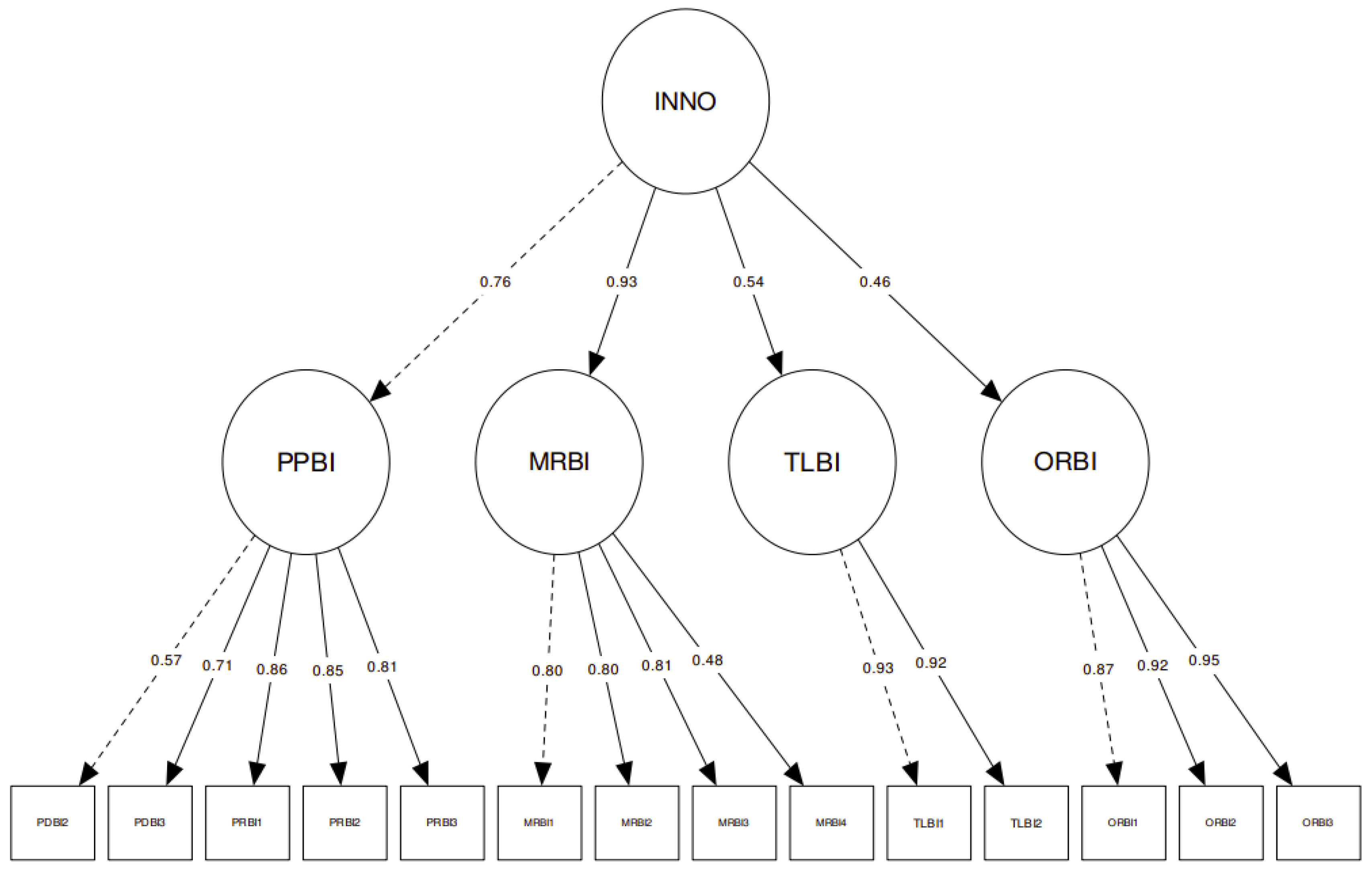

5.3.5. Innovation Adoption

5.4. Direct, Mediation and Moderated Mediation Effects

5.4.1. Direct Effect between SSCM and SFP

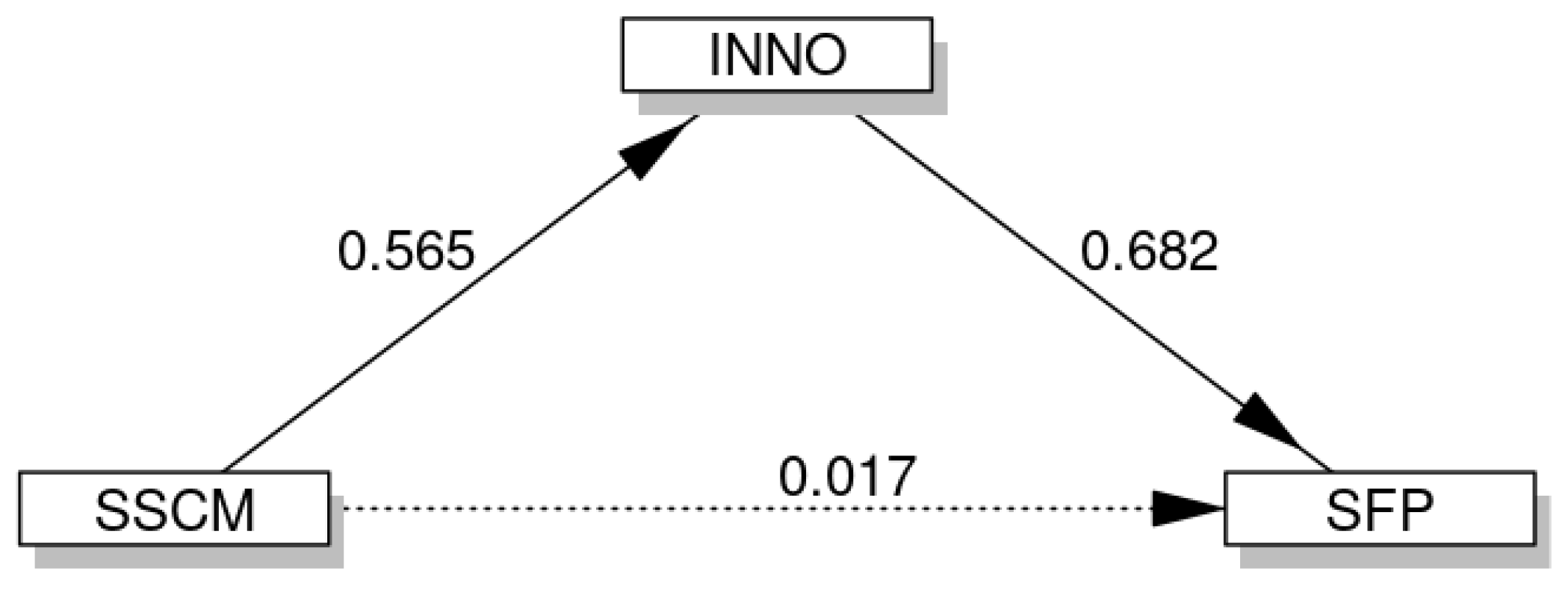

5.4.2. Mediation Effects of Innovation Adoption

5.5. Moderated Mediation Effects of Socio-Cultural Factors

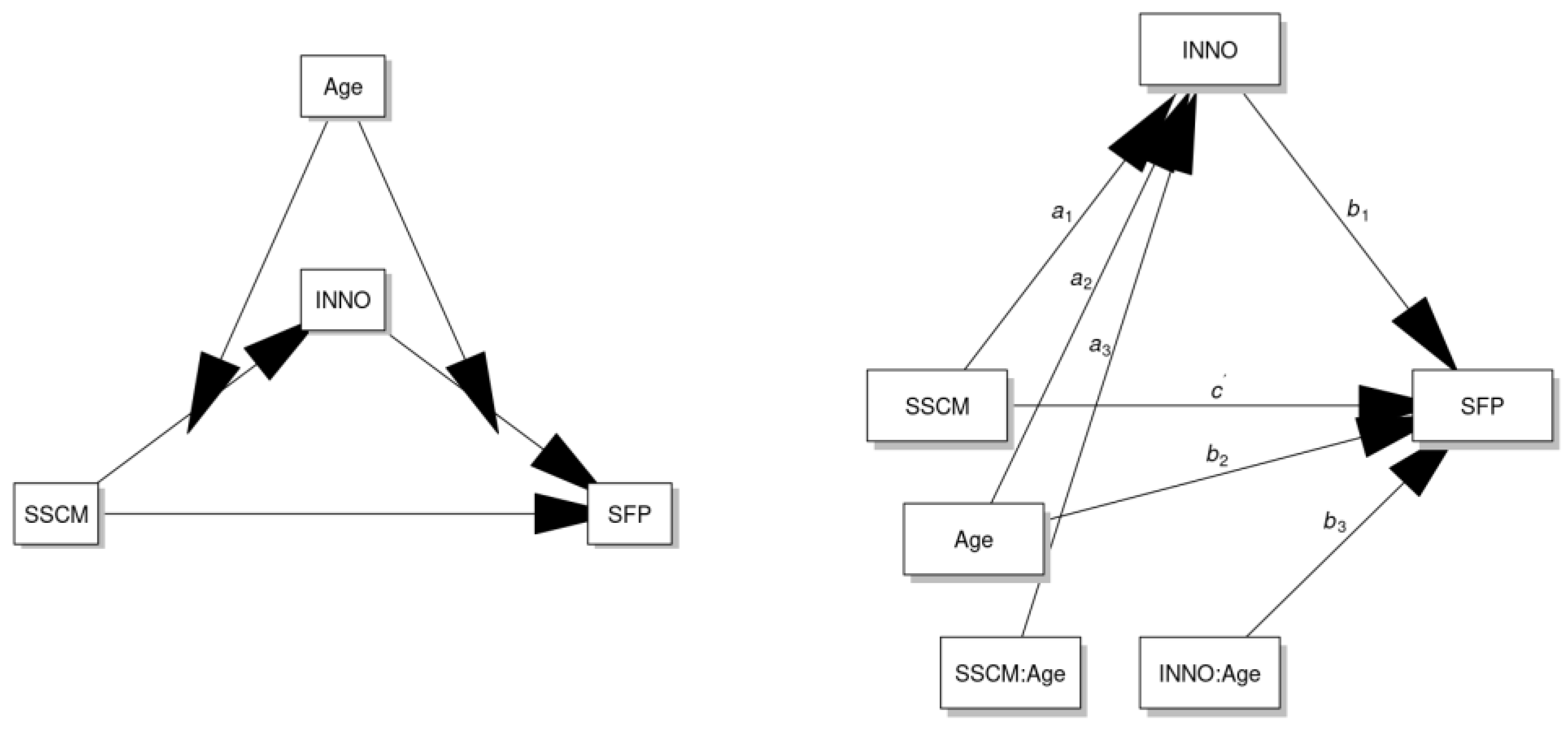

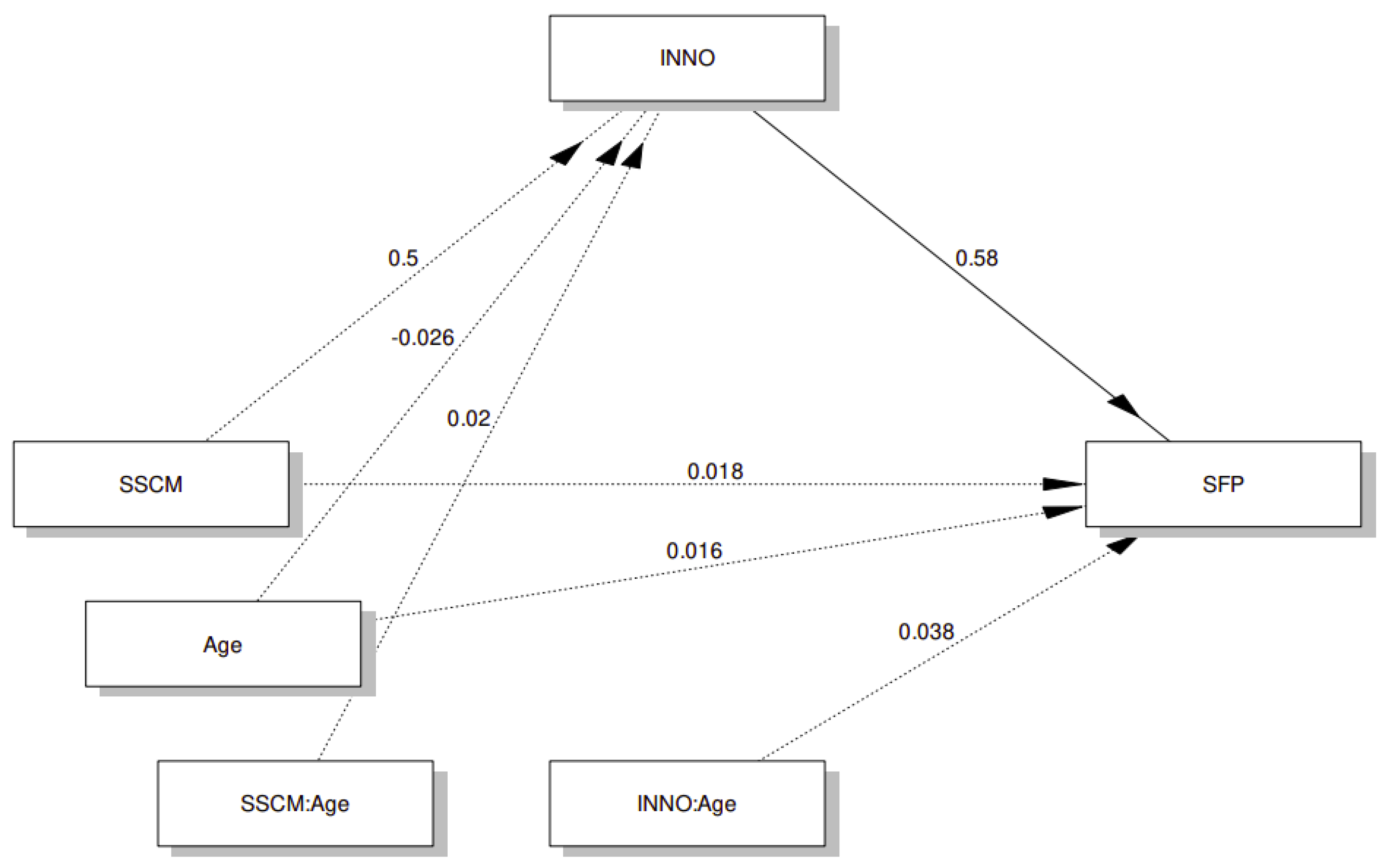

5.5.1. Moderated Mediation Effects of Age

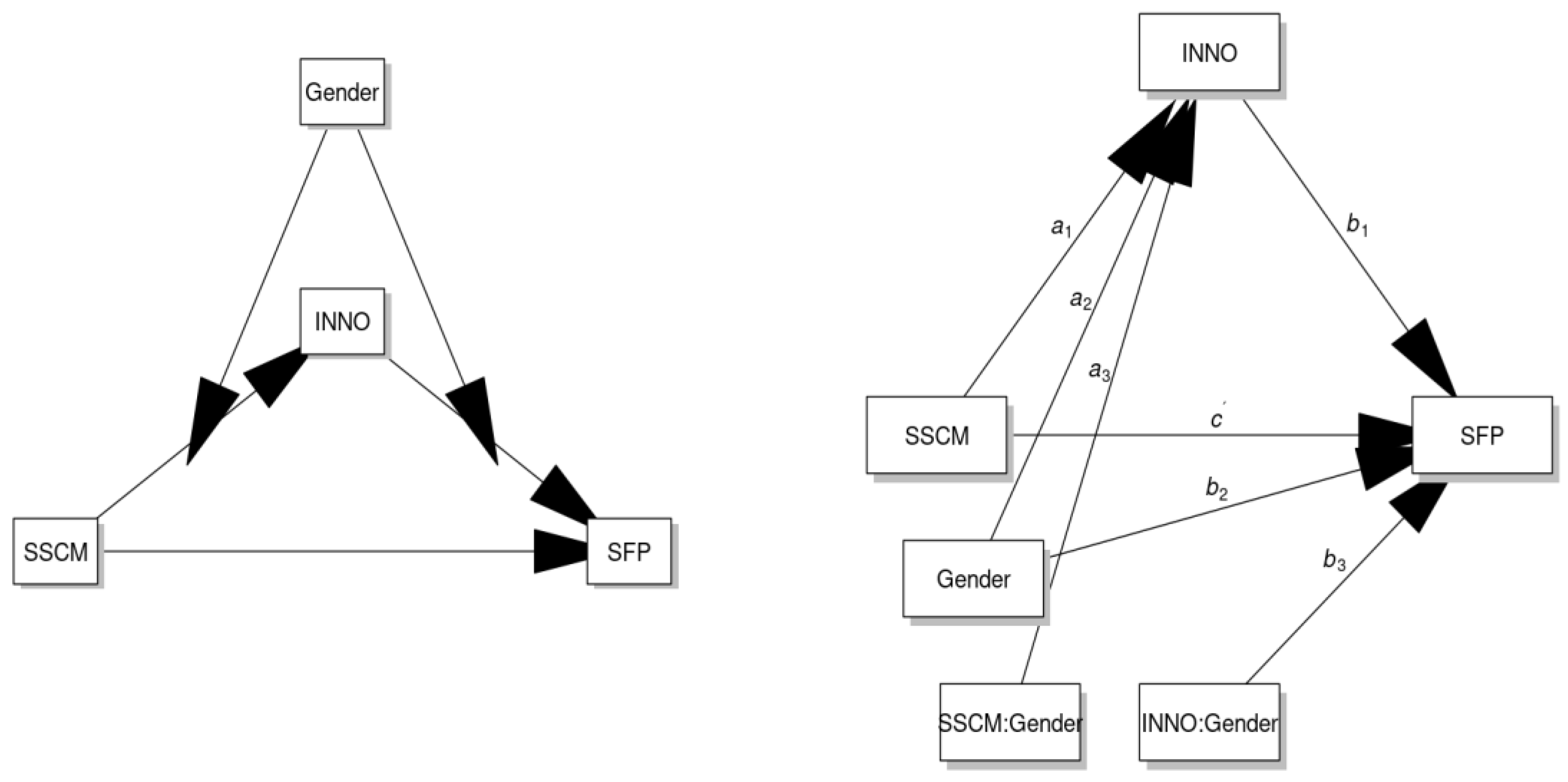

5.5.2. Moderated Mediation Effects of Gender

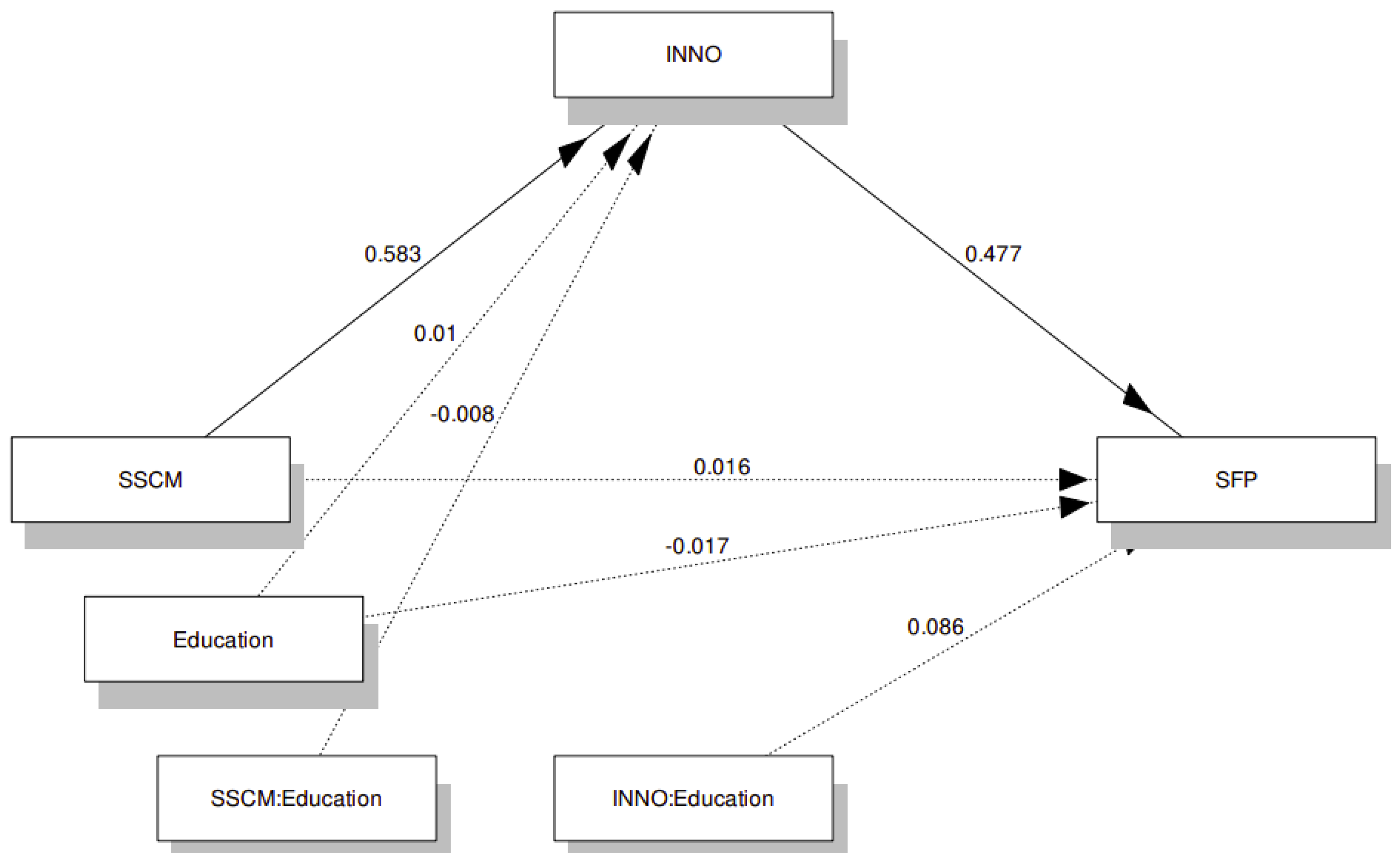

5.5.3. Moderated Mediation Effects of Education

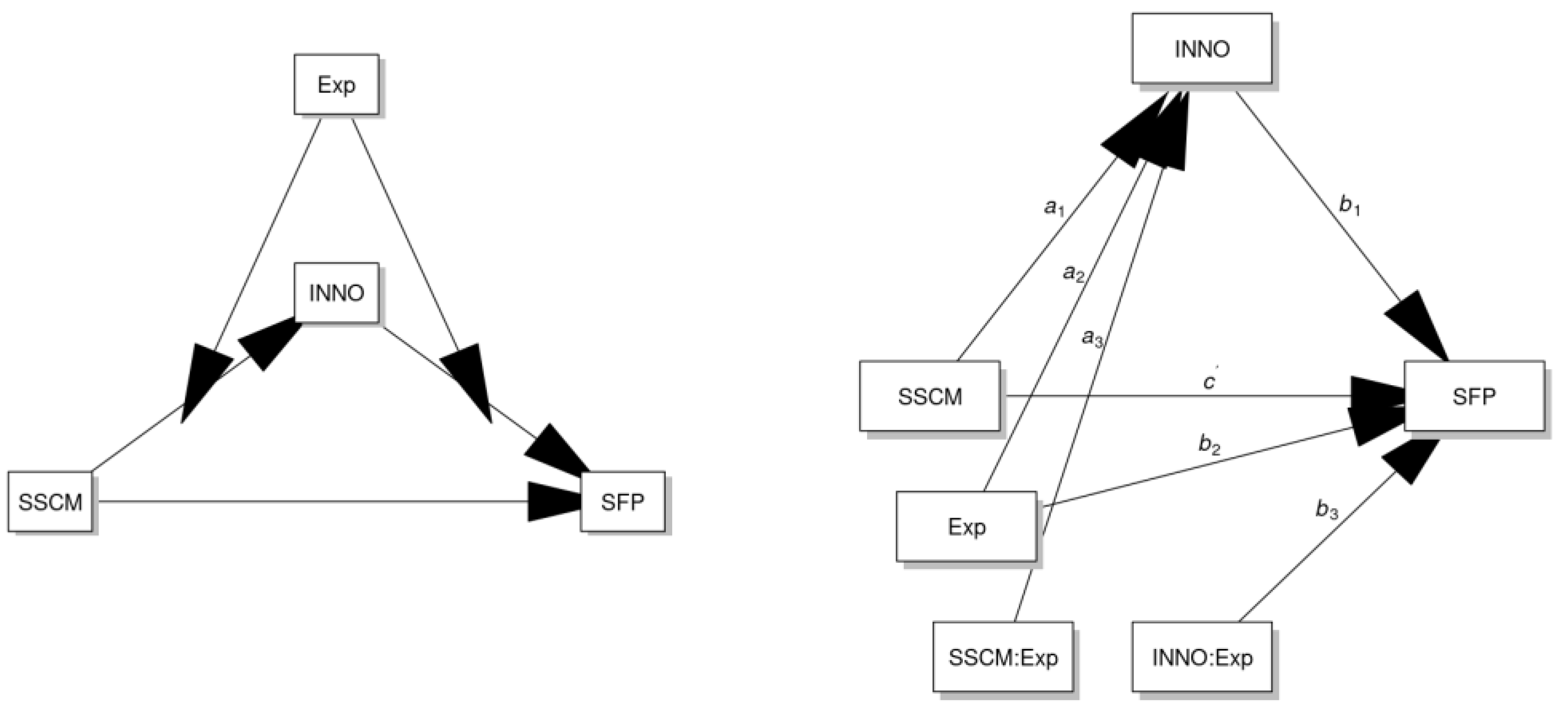

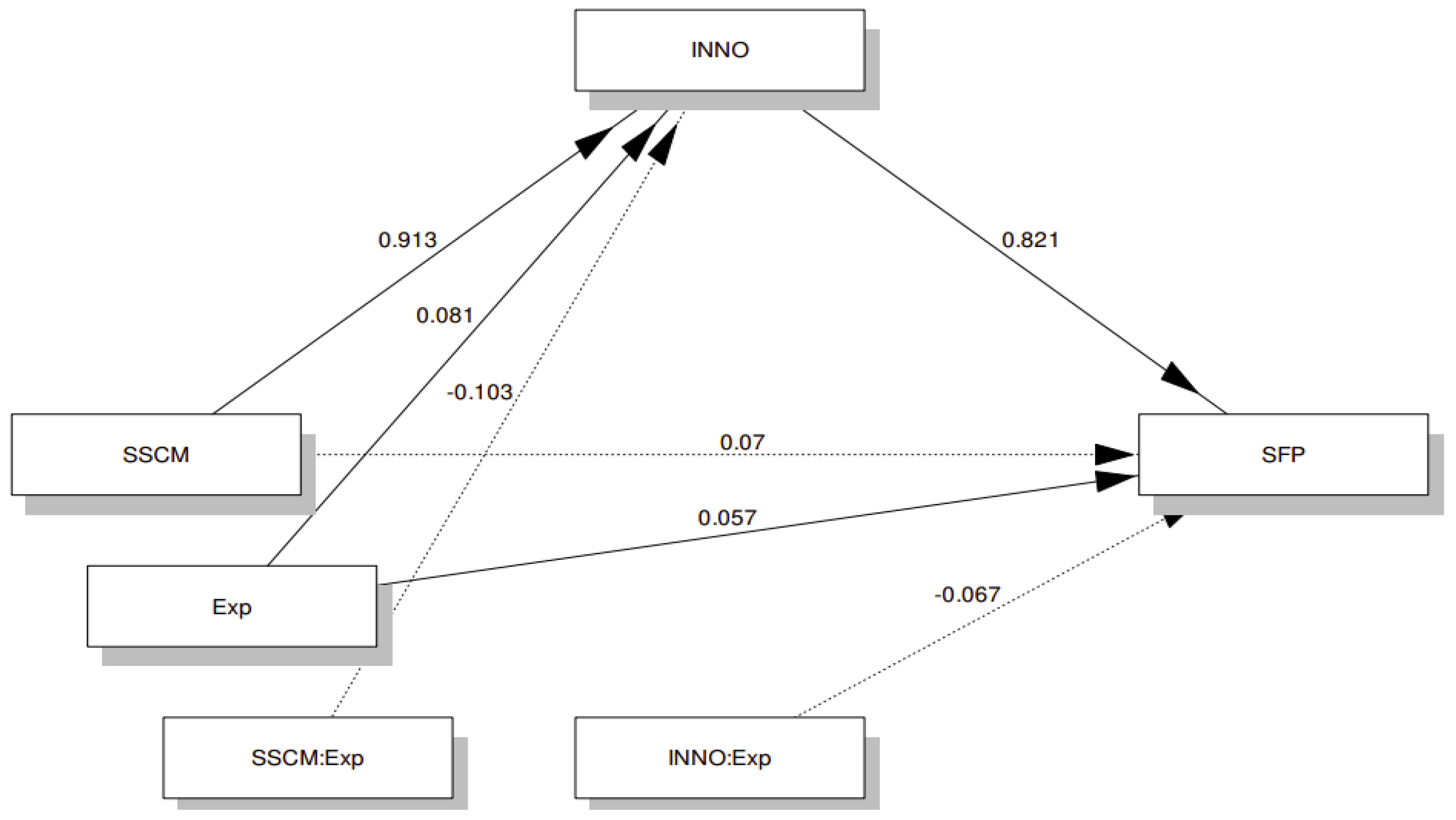

5.5.4. Moderated Mediation Effects of Total Experience

6. Findings and Discussion

- (a)

- The need for a scale for assessing SSCM practices of tier one tourism supply chain with (input—process—output) internal and external consumers, and tier two service/product providers in the tourism industry.

- (b)

- The service–product continuum of the tourism industry, thus a three construct higher-order scale (SPSSCM, SSSSCM, and SDSSCM) for assessing the SSCM practices.

- (c)

- Three separate higher-order scales for assessing SSCM, SFP and INNO in the food and beverage service sector.

- (d)

- The direct effects of SSCM on SFP.

- (e)

- The mediating (indirect) effects of Innovation adoption in the relationship between SSCM and SFP.

- (f)

- The moderated mediation effects of socio-demographic factors in the mediated relationship between SSCM and SFP through INNO.

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Entrepreneurial and Managerial Implications

7.3. Social Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research, and Concluding Remarks

8.1. Limitations and Future Research

8.2. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharafuddin, M.A.; Madhavan, M. Thematic Evolution of Blue Tourism: A Scientometric Analysis and Systematic Review. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 0972150920966885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Huang, G.Q. Tourism Supply Chain Management: A New Research Agenda. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.M.; Hussien, F.M. The Effects of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from Restaurants in Egypt. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.-Z.; Hsieh, C.-C. The Impact of Restaurants’ Green Supply Chain Practices on Firm Performance. Sustainability 2016, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-F.; Chen, S.-P.; Lee, Y.-C.; Tsai, C.-T. (Simon) Developing Green Management Standards for Restaurants: An Application of Green Supply Chain Management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-F.; Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chung, Y.-C. Expert Concepts of Sustainable Service Innovation in Restaurants in Taiwan. Sustainability 2016, 8, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivkov, M.; Blešić, I.; Simat, K.; Demirović, D.; Božić, S. Innovations in the Restaurant Industry—An Exploratory Study. Econ. Agric. 2016, 63, 1169–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R.; Sardeshmukh, S.R. Creativity and Innovation in the Restaurant Sector: Supply-Side Processes and Barriers to Implementation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thailand: New Restaurant Business Models and Strategies during COVID-19. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/thailand-new-restaurant-business-models-and-strategies-during-COVID-19 (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; John Wiley & Son Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-1-84112-084-3. [Google Scholar]

- Szpilko, D. Tourism Supply Chain–Overview of Selected Literature. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Scott, N. Food Tourism Reviewed Using the Paradigm Funnel Approach. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickorish, L.J.; Jenkins, C.L. Introduction to Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-136-39192-7. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.L.J.; Xiao, H. Culinary Tourism Supply Chains: A Preliminary Examination. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, D.W.; Advertising, C. The Marketing of Services; Heinemann: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. Service Management and Marketing; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R.C.; Sturman, M.C.; Heaton, C.P. Managing Quality Service in Hospitality: How Organizations Achieve Excellence in the Guest Experience; Delmar, Cengage Learning: Clifton Park, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4390-6032-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R.C.; Sturman, M.C. Managing Hospitality Organizations: Achieving Excellence in the Guest Experience; SAGE Publications: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5443-5684-6. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R.C. Sustainability Indicators of a Small Restaurant Business: A Case of a Coffee Shop in Thailand; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Özveri, O.; Güçlü, P.; Aycin, E. Evaluation of Service Supply Chain Performance Criteria with Danp Method. ASSAM Uluslararası Hakemli Dergi 2015, 2, 104–119. [Google Scholar]

- Piboonrungroj, P. Supply Chain Collaboration in Tourism: A Transaction Cost Economics Analysis. Int. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2015, 4, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Mifll, M. Menu Development and Analysis in UK Restaurant Chains. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2001, 3, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, L.Y.L. The Application of Menu Engineering and Design in Asian Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linassi, R.; Alberton, A.; Marinho, S.V. Menu Engineering and Activity-Based Costing: An Improved Method of Menu Planning. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1417–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx-Pienaar, N.; Rand, G.D.; Viljoen, A.; Fisher, H. Food Wastage: A Concern across the South African Quick Service Restaurant Supply Chain; WIT Press: Seville, Spain, 2018; pp. 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Aarnio, T.; Hämäläinen, A. Challenges in Packaging Waste Management in the Fast Food Industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, S.E. Customer-supplier Duality and Bidirectional Supply Chains in Service Organizations. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000, 11, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.W.; Lee, Y.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Hwang, M.K. A Framework for Measuring the Performance of Service Supply Chain Management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2012, 62, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Kang, H.; Choi, H.; Olds, D. Managerial Attitudes towards Green Practices in Educational Restaurant Operations: An Importance-Performance Analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2020, 32, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R.; Sardeshmukh, S.R. Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Restaurant Performance: A Higher-Order Structural Model. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hao, Y. Layout Design For Service Operation Of Mass Customization: A Case Of Chinese Restaurant. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, Troyes, France, 25–27 October 2006; Volume 1, pp. 668–673. [Google Scholar]

- Iravani, S.M.; Van Oyen, M.P.; Sims, K.T. Structural Flexibility: A New Perspective on the Design of Manufacturing and Service Operations. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negus, R. Pub, Bar or Restaurant? J. Retail. Leis. Prop. 2004, 3, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razza, F.; Fieschi, M.; Innocenti, F.D.; Bastioli, C. Compostable Cutlery and Waste Management: An LCA Approach. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnurr, R.E.J.; Alboiu, V.; Chaudhary, M.; Corbett, R.A.; Quanz, M.E.; Sankar, K.; Srain, H.S.; Thavarajah, V.; Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. Reducing Marine Pollution from Single-Use Plastics (SUPs): A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinise, S.N.; Roos, C.; Oelofse, S.H.; Muswema, A.P. “Implementing the Waste Hierarchy”—Assessing Recycling Potential of Restaurant Waste; Wastecon: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Khalid, N.; Javed, H.M.U.; Islam, D.M.Z. Consumer Adoption of Online Food Delivery Ordering (OFDO) Services in Pakistan: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Situation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.X.; Li, X.; Lau, V.M.-C.; Zhu, V.Z. To Survive or to Thrive? China’s Luxury Hotel Restaurants Entering O2O Food Delivery Platforms amid the COVID-19 Crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Van Hoof, H.B.; Park, S. The Impact of Board Composition on Firm Performance in the Restaurant Industry: A Stewardship Theory Perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2121–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhum, W. The Impact of Sustainability Concept on Supply Chain Dynamic Capabilities. PJMS 2019, 20, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qorri, A.; Gashi, S.; Kraslawski, A. Performance Outcomes of Supply Chain Practices for Sustainable Development: A Meta-Analysis of Moderators. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C.Y. Exploring Group-Buying Platforms for Restaurant Revenue Management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C.Y.; Lee, S.; Mattila, A.; Hu, C. Restaurant Revenue Management: Do Perceived Capacity Scarcity and Price Differences Matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimes, S.E.; Chase, R.B.; Choi, S.; Lee, P.Y.; Ngonzi, E.N. Restaurant Revenue Management: Applying Yield Management to the Restaurant Industry. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 1998, 39, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perramon, J.; Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M.; Llach, J.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Green Practices in Restaurants: Impact on Firm Performance. Oper. Manag. Res. 2014, 7, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, R.; Juyal, D.; Rawal, Y.S. A Critical Analysis of the Restaurant Industry’s Effect on Environment Sustainability. Sci. Prog. Res. (SPR) 2022, 2, 464–471. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.J.; Zheng, T. Assessment of the Environmental Sustainability of Restaurants in the U.S.: The Effects of Restaurant Characteristics on Environmental Sustainability Performance. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Cho, M. Green Supply Chain Management Implemented by Suppliers as Drivers for SMEs Environmental Growth with a Focus on the Restaurant Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Li, H. Life Cycle Environmental Performance of Two Restaurant Food Waste Management Strategies at Shenzhen, China. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, N.M.; Muhammad, R.; Nazari, N.; Zaidi, N. Green Technology Implementation at Fast Food Restaurants in Selangor. J. Glob. Bus. Soc. Entrep. (GBSE) 2022, 7, 13. [Google Scholar]

- UNCCD Library. Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; Living Planet Report; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-2-940529-99-5. [Google Scholar]

- Waste Water from Hotel-Restaurant Complex as a Potential Threat to Biodiversity of Aquatic Ecosystems (p.)\textbar News of Dnipropetrovsk State Agrarian and Economic University. Available online: http://ojs.dsau.dp.ua/index.php/vestnik/article/view/278/0 (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Beriss, D.; Sutton, D. The Restaurants Book: Ethnographies of Where We Eat; A&C Black: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-84520-755-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cajander, N.; Reiman, A. High Performance Work Practices and Well-Being at Restaurant Work. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2019, 9, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4221-6197-5. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Kwon, K. The Remodeling of Brand Image of the Time-Honored Restaurant Brand of Wuhan Based on Emotional Design; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Božić, A.; Milošević, S. Contemporary Trends in the Restaurant Industry and Gastronomy. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nualnoom, P. Food Self-Sufficiency of Tourist Attraction Site: A Case Study of Phang Nga Province, Thailand. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 10233–10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Fernando, M.S.C.L. Strategies to Improve Employees’ Work Efficiency in One Brance of ABC Thai Restaurant. ABAC ODI J. Vis. Action Outcome 2021, 8, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-J.; Chen, K.-S.; Wang, Y.-Y. Green Practices in the Restaurant Industry from an Innovation Adoption Perspective: Evidence from Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-F.; Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Yu, T.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-T. Identifying the Critical Factors for Sustainable Marketing in the Catering: The Influence of Big Data Applications, Marketing Innovation, and Technology Acceptance Model Factors. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, S.M.; Sharp, J.S.; Moore, R.H.; Stinner, D.H. Restaurants, Chefs and Local Foods: Insights Drawn from Application of a Diffusion of Innovation Framework. Agric. Hum. Values 2009, 26, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.; Griswold, M. Firms in the Restaurant Industry. Int. J. Business Social Sci. 2011, 2, 221–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J.A.; Pett, T.L. Small-Firm Performance: Modeling the Role of Product and Process Improvements. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olimovich, D.I.; Baxtiyorovich, T.M.; Chorievich, B.A. Description of Technological Processes in Restaurant Services. JournalNX 2020, 6, 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.; Lee, H. What Makes Restaurateurs Adopt Healthy Restaurant Initiatives? Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2583–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R. Investigating the Moderating Role of Education on a Structural Model of Restaurant Performance Using Multi-Group PLS-SEM Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A. Technological Disruptions in Restaurant Services: Impact of Innovations and Delivery Services. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batat, W. How Augmented Reality (AR) Is Transforming the Restaurant Sector: Investigating the Impact of “Le Petit Chef” on Customers’ Dining Experiences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 172, 121013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-H.; Lin, C.-W.; Shih, K.-H. A Technology Acceptance Model for the Perception of Restaurant Service Robots for Trust, Interactivity, and Output Quality. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2018, 16, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, B.; Sessa, M.R.; Sica, D.; Malandrino, O. Exploring the Link Between Customers’ Safety Perception and the Use of Information Technology in the Restaurant Sector During the COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Research and Innovation Forum 2021, Online, 7–9 April 2021; Visvizi, A., Troisi, O., Saeedi, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Cantele, S.; Cassia, F. Sustainability Implementation in Restaurants: A Comprehensive Model of Drivers, Barriers, and Competitiveness-Mediated Effects on Firm Performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Rajeev, A.; Padhi, S.S.; Pati, R.K. Supply Chain Sustainability and Performance of Firms: A Meta-Analysis of the Literature. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 137, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-F.; Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Zhang, S.-N. The Critical Criteria for Innovation Entrepreneurship of Restaurants: Considering the Interrelationship Effect of Human Capital and Competitive Strategy a Case Study in Taiwan. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. Regression Analysis for Categorical Moderators; Regression analysis for categorical moderators; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-57230-969-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Gottfredson, R.K. Best-Practice Recommendations for Estimating Interaction Effects Using Moderated Multiple Regression. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Grávalos-Gastaminza, M.A.; Pérez-Calañas, C. Facebook and the Intention of Purchasing Tourism Products: Moderating Effects of Gender, Age and Marital Status. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hem, L.E.; Iversen, N.M.; Nysveen, H. Effects of Ad Photos Portraying Risky Vacation Situations on Intention to Visit a Tourist Destination. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2003, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Lee, C.-K.; Chung, N. Investigating the Role of Trust and Gender in Online Tourism Shopping in South Korea. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 37, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Kvasova, O.; Christodoulides, P. Drivers and Outcomes of Green Tourist Attitudes and Behavior: Sociodemographic Moderating Effects. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-B.; Kim, K.-H. Structural Relationships among Rural Tourism Motivation, Satisfaction, and Loyalty Including the Moderating Effects of Gender. Korean J. Community Living Sci. 2011, 22, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suki, N.M. Moderating Role of Gender in the Relationship between Hotel Service Quality Dimensions and Tourist Satisfaction. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 15, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafuddin, M.A. Types of Tourism in Thailand. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2015, 12, 210–219. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-1-4106-0108-7. [Google Scholar]

- Toplak, M.E.; Sorge, G.B.; Flora, D.B.; Chen, W.; Banaschewski, T.; Buitelaar, J.; Ebstein, R.; Eisenberg, J.; Franke, B.; Gill, M.; et al. The Hierarchical Factor Model of ADHD: Invariant across Age and National Groupings?: Hierarchical Factor Model in Child ADHD. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebesutani, C.; McLeish, A.C.; Luberto, C.M.; Young, J.; Maack, D.J. A Bifactor Model of Anxiety Sensitivity: Analysis of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2014, 36, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. Development and Validation of a Scale for Measuring Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1344–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangur, S.; Ercan, I. Comparison of Model Fit Indices Used in Structural Equation Modeling Under Multivariate Normality. J. Mod. App. Stat. Meth. 2015, 14, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Ip, E.H.; Dubé, L. An Alternative to Post-Hoc Model Modification in Confirmatory Factor Analysis: The Bayesian Lasso. Psychol. Methods 2017, 22, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.S.; Huba, G.J. A Fit Index for Covariance Structure Models under Arbitrary GLS Estimation. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1985, 38, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A Reliability Coefficient for Maximum Likelihood Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, T.D.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y.; Miller, P.; Quick, C.; Garnier-Villarreal, M.; Selig, J.; Boulton, A.; Preacher, K. Package ‘SemTools’ 2016. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/semTools/citation.html (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, K.-W. ProcessR: Implementation of the “PROCESS” Macro, Version 0.2.6. 2021. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/processR/index.html (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, S.; Knight, J. Externality Effects of Education: Dynamics of the Adoption and Diffusion of an Innovation in Rural Ethiopia. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2004, 53, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y. Education and Innovation Adoption in Agriculture: Evidence from Hybrid Rice in China. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1991, 73, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.E.; Loucks, S.F.; Rutherford, W.L.; Newlove, B.W. Levels of Use of the Innovation: A Framework for Analyzing Innovation Adoption. J. Teach. Educ. 1975, 26, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boahene, K.; Snijders, T.A.; Folmer, H. An Integrated Socioeconomic Analysis of Innovation Adoption: The Case of Hybrid Cocoa in Ghana. J. Policy Model. 1999, 21, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafuddin, M.A.; Sawad, B.P.; Wongwai, S. Modeling and Mapping Personal Learning Environment of Thai International Higher Education Students. Asian J. Educ. Train. 2018, 4, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tanyong, S.; Sharafuddin, M.A. Understanding Personal Learning Environment Perspectives of Thai International Tourism and Hospitality Higher Education Students. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Holmström, J. Needs and Technology Adoption: Observation from BIM Experience. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2015, 22, 128–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.-W.; Yen, D.C. To Buy or Not to Buy Experience Goods Online: Perspective of Innovation Adoption Barriers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Williams, M.D. Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Attributes: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Existing Research. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2014, 31, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongmonta, S. Post-COVID 19 Tourism Recovery and Resilience: Thailand Context. Int. J. Multidiscip. Manag. Tour. 2021, 5, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Fernandez, M. Territorial Tourism Resilience in the COVID-19 Summer. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estiri, M.; Heidary Dahooie, J.; Skare, M. COVID-19 Crisis and Resilience of Tourism SME’s: A Focus on Policy Responses. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–25 | 18 | 10.112 | 10.112 |

| 26–33 | 59 | 33.146 | 43.258 |

| 34–41 | 54 | 30.337 | 73.596 |

| 42–49 | 36 | 20.225 | 93.82 |

| 50 above | 11 | 6.18 | 100 |

| Gender | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

| Male | 67 | 37.64 | 37.64 |

| Female | 111 | 62.36 | 100 |

| Education | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

| High School | 32 | 17.978 | 17.978 |

| Bachelor | 105 | 58.989 | 76.966 |

| Master | 9 | 5.056 | 82.022 |

| Others | 32 | 17.978 | 100 |

| Profession | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

| Entrepreneur (Owner of the Hotel/Restaurant) | 98 | 55.056 | 55.056 |

| Manager | 19 | 10.674 | 65.73 |

| F&B Service Staff/Supervisor | 45 | 25.281 | 91.011 |

| Others | 9 | 5.056 | 96.067 |

| Chef | 6 | 3.371 | 99.438 |

| Store Manager/In-charge | 1 | 0.562 | 100 |

| Total_Experience | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

| Less than 3 years | 22 | 12.36 | 12.36 |

| 3–5 Years | 32 | 17.978 | 30.337 |

| 5–10 Years | 32 | 17.978 | 48.315 |

| More than 10 Years | 92 | 51.685 | 100 |

| Cuisine | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

| Thai | 143 | 80.337 | 80.337 |

| Korean | 1 | 0.562 | 80.899 |

| Japanese | 2 | 1.124 | 82.022 |

| Chinese | 1 | 0.562 | 82.584 |

| Indian | 1 | 0.562 | 83.146 |

| Western | 11 | 6.18 | 89.326 |

| Multi-cuisine | 9 | 5.056 | 94.382 |

| Others | 10 | 5.618 | 100 |

| If Item Dropped | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | ω | α | Item | ω | α | Item | ω | α |

| SPSSCM3 | 0.909 | 0.933 | PDBI2 | 0.873 | 0.891 | ECP3 | 0.942 | 0.944 |

| SPSSCM4 | 0.9 | 0.929 | PDBI3 | 0.875 | 0.889 | ECP4 | 0.944 | 0.946 |

| SPSSCM5 | 0.903 | 0.932 | PRBI1 | 0.837 | 0.887 | ECP6 | 0.942 | 0.943 |

| SPSSCM7 | 0.898 | 0.928 | PRBI2 | 0.837 | 0.888 | ECP8 | 0.943 | 0.944 |

| SPSSCM8 | 0.897 | 0.928 | PRBI3 | 0.833 | 0.886 | OPP3 | 0.938 | 0.94 |

| SPSSCM9 | 0.902 | 0.93 | MRBI1 | 0.828 | 0.885 | OPP4 | 0.939 | 0.941 |

| SPSSCM10 | 0.899 | 0.929 | MRBI2 | 0.865 | 0.887 | OPP5 | 0.939 | 0.94 |

| SPSSCM11 | 0.897 | 0.928 | MRBI3 | 0.857 | 0.885 | OPP6 | 0.94 | 0.941 |

| SPSSCM12 | 0.9 | 0.93 | MRBI4 | 0.886 | 0.898 | OPP7 | 0.938 | 0.941 |

| SSSSCM1 | 0.896 | 0.929 | TLBI1 | 0.866 | 0.888 | ENP1 | 0.94 | 0.942 |

| SSSSCM2 | 0.903 | 0.932 | TLBI2 | 0.866 | 0.888 | ENP2 | 0.938 | 0.941 |

| SSSSCM3 | 0.9 | 0.931 | ORBI1 | 0.872 | 0.891 | ENP3 | 0.938 | 0.941 |

| SSSSCM4 | 0.892 | 0.928 | ORBI2 | 0.869 | 0.889 | ENP4 | 0.937 | 0.94 |

| SSSSCM5 | 0.894 | 0.929 | ORBI3 | 0.869 | 0.889 | SCP1 | 0.939 | 0.942 |

| SDSSCM1 | 0.894 | 0.929 | SCP3 | 0.94 | 0.943 | |||

| SDSSCM2 | 0.924 | 0.928 | SCP4 | 0.94 | 0.942 | |||

| SDSSCM3 | 0.923 | 0.927 | ||||||

| SDSSCM4 | 0.924 | 0.928 | ||||||

| SDSSCM5 | 0.923 | 0.932 | ||||||

| SDSSCM6 | 0.923 | 0.929 | ||||||

| Factor Loadings for SSCM | Factor Loadings for Innovation | Factor Loadings SFP | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |||

| SPSSCM10 | 0.866 | PRBI2 | 0.918 | OPP5 | 0.977 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM7 | 0.839 | PRBI1 | 0.905 | OPP4 | 0.969 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM8 | 0.789 | PRBI3 | 0.743 | OPP6 | 0.841 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM12 | 0.769 | PDBI3 | 0.708 | OPP3 | 0.576 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM4 | 0.768 | PDBI2 | 0.502 | ECP6 | 0.946 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM11 | 0.739 | ORBI3 | 0.946 | ECP8 | 0.817 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM5 | 0.714 | ORBI2 | 0.886 | ECP4 | 0.675 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM3 | 0.516 | ORBI1 | 0.833 | ECP3 | 0.632 | ||||||||

| SPSSCM9 | 0.41 | MRBI3 | 0.833 | ENP3 | 0.967 | ||||||||

| SDSSCM4 | 1.034 | MRBI2 | 0.752 | ENP4 | 0.658 | ||||||||

| SDSSCM3 | 1.014 | MRBI1 | 0.606 | ENP1 | 0.645 | ||||||||

| SDSSCM2 | 1.007 | MRBI4 | 0.507 | SCP3 | 0.77 | ||||||||

| SDSSCM6 | 0.645 | TLBI1 | 0.88 | SCP4 | 0.708 | ||||||||

| SDSSCM5 | 0.561 | TLBI2 | 0.806 | SCP2 | 0.521 | ||||||||

| SDSSCM1 | 0.432 | ||||||||||||

| SSSSCM2 | 0.998 | ||||||||||||

| SSSSCM3 | 0.874 | ||||||||||||

| SSSSCM4 | 0.454 | ||||||||||||

| SSCM | INNO | SFP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| chisq | 281.278 | 203.172 | 167.475 |

| df | 116 | 73 | 73 |

| Chiqsq/df | 2.42 | 2.78 | 2.29 |

| p value | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| srmr | 0.095 | 0.098 | 0.059 |

| cfi | 0.926 | 0.923 | 0.949 |

| tli | 0.914 | 0.904 | 0.937 |

| nnfi | 0.914 | 0.904 | 0.937 |

| nfi | 0.881 | 0.886 | 0.915 |

| ifi | 0.927 | 0.923 | 0.950 |

| rfi | 0.861 | 0.858 | 0.894 |

| rni | 0.926 | 0.923 | 0.949 |

| Effect | Equation | Estimate | 95% Bootstrap CI Boot.CI.Type = Perc |

|---|---|---|---|

| direct | c | 0.402 | (0.263 to 0.556) |

| Variables | Predictors | Label | B | SE | z | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFP | SSCM | c | 0.402 | 0.074 | 5.436 | <0.001 | 0.356 |

| Effect | Equation | Estimate | 95% Bootstrap CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| indirect | (a)*(b) | 0.386 | (0.253 to 0.520) |

| direct | c | 0.017 | (−0.130 to 0.180) |

| total | direct + indirect | 0.402 | (0.265 to 0.558) |

| prop.mediated | indirect/total | 0.959 | (0.618 to 1.448) |

| Variables | Predictors | Label | B | SE | z | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INNO | SSCM | a | 0.565 | 0.075 | 7.509 | <0.001 | 0.516 |

| SFP | SSCM | c | 0.017 | 0.079 | 0.212 | 0.832 | 0.015 |

| SFP | INNO | b | 0.682 | 0.080 | 8.519 | <0.001 | 0.660 |

| Effect | Equation | Estimate | 95% Bootstrap CI Boot.CI.Type = Perc |

|---|---|---|---|

| indirect | (a1+a3*Age.mean)*(b1+b3*Age.mean) | 0.382 | (0.250 to 0.516) |

| direct | c | 0.018 | (−0.123 to 0.180) |

| total | direct+indirect | 0.400 | (0.248 to 0.554) |

| prop.mediated | indirect/total | 0.955 | (0.619 to 1.425) |

| indirect.below | (a1+a3*(Age.mean-sqrt(Age.var)))*(b1+b3*(Age.mean-sqrt(Age.var))) | 0.345 | (0.152 to 0.566) |

| indirect.above | (a1+a3*(Age.mean+sqrt(Age.var)))*(b1+b3*(Age.mean+sqrt(Age.var))) | 0.420 | (0.250 to 0.594) |

| direct.below | c | 0.018 | (−0.123 to 0.180) |

| direct.above | c | 0.018 | (−0.123 to 0.180) |

| total.below | direct.below+indirect.below | 0.363 | (0.147 to 0.581) |

| total.above | direct.above+indirect.above | 0.438 | (0.239 to 0.624) |

| prop.mediated.below | indirect.below/total.below | 0.950 | (0.553 to 1.618) |

| prop.mediated.above | indirect.above/total.above | 0.959 | (0.653 to 1.426) |

| Variables | Predictors | Label | B | SE | z | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INNO | SSCM | a1 | 0.500 | 0.257 | 1.948 | 0.051 | 0.459 |

| INNO | Age | a2 | −0.026 | 0.025 | −1.018 | 0.308 | −0.080 |

| INNO | SSCM:Age | a3 | 0.020 | 0.079 | 0.254 | 0.800 | 0.056 |

| SFP | SSCM | c | 0.018 | 0.080 | 0.228 | 0.820 | 0.017 |

| SFP | INNO | b1 | 0.580 | 0.184 | 3.157 | 0.002 | 0.584 |

| SFP | Age | b2 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 1.016 | 0.310 | 0.052 |

| SFP | INNO:Age | b3 | 0.038 | 0.051 | 0.744 | 0.457 | 1.120 |

| Effect | Equation | Estimate | 95% Bootstrap CI Boot.CI.Type = Perc |

|---|---|---|---|

| indirect | (a1+a3*Gender.mean)*(b1+b3*Gender.mean) | 0.398 | (0.260 to 0.538) |

| direct | c | −0.005 | (−0.154 to 0.162) |

| total | direct+indirect | 0.393 | (0.231 to 0.556) |

| prop.mediated | indirect/total | 1.012 | (0.673 to 1.548) |

| indirect.below | (a1+a3*(Gender.mean-sqrt(Gender.var)))*(b1+b3*(Gender.mean-sqrt(Gender.var))) | 0.437 | (0.281 to 0.600) |

| indirect.above | (a1+a3*(Gender.mean+sqrt(Gender.var)))*(b1+b3*(Gender.mean+sqrt(Gender.var))) | 0.357 | (0.165 to 0.559) |

| direct.below | c | −0.005 | (−0.154 to 0.162) |

| direct.above | c | −0.005 | (−0.154 to 0.162) |

| total.below | direct.below+indirect.below | 0.432 | (0.263 to 0.628) |

| total.above | direct.above+indirect.above | 0.352 | (0.132 to 0.567) |

| prop.mediated.below | indirect.below/total.below | 1.011 | (0.694 to 1.493) |

| prop.mediated.above | indirect.above/total.above | 1.014 | (0.622 to 1.837) |

| Variables | Predictors | Label | B | SE | z | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INNO | SSCM | a1 | 0.517 | 0.235 | 2.199 | 0.028 | 0.472 |

| INNO | Gender | a2 | −0.087 | 0.049 | −1.792 | 0.073 | −0.123 |

| INNO | SSCM:Gender | a3 | 0.032 | 0.164 | 0.194 | 0.846 | 0.046 |

| SFP | SSCM | c | −0.005 | 0.002 | −0.060 | 0.952 | −0.004 |

| SFP | INNO | b1 | 1.001 | 0.213 | 4.693 | <0.001 | 0.816 |

| SFP | Gender | b2 | 0.074 | 0.046 | 1.628 | 0.104 | 0.085 |

| SFP | INNO:Gender | b3 | −0.185 | 0.128 | −1.440 | 0.150 | −0.252 |

| Effect | Equation | Estimate | 95% Bootstrap CI Boot.CI.Type = Perc |

|---|---|---|---|

| indirect | (a1+a3*Education.mean)*(b1+b3*Education.mean) | 0.390 | (0.266 to 0.531) |

| direct | c | 0.016 | (−0.141 to 0.174) |

| total | direct+indirect | 0.406 | (0.269 to 0.577) |

| prop.mediated | indirect/total | 0.961 | (0.642 to 1.445) |

| indirect.below | (a1+a3*(Education.mean-sqrt(Education.var)))*(b1+b3*(Education.mean-sqrt(Education.var))) | 0.354 | (0.200 to 0.547) |

| indirect.above | (a1+a3*(Education.mean+sqrt(Education.var)))*(b1+b3*(Education.mean+sqrt(Education.var))) | 0.426 | (0.250 to 0.615) |

| direct.below | c | 0.016 | (−0.141 to 0.174) |

| direct.above | c | 0.016 | (−0.141 to 0.174) |

| total.below | direct.below+indirect.below | 0.369 | (0.192 to 0.577) |

| total.above | direct.above+indirect.above | 0.441 | (0.245 to 0.637) |

| prop.mediated.below | indirect.below/total.below | 0.958 | (0.597 to 1.569) |

| prop.mediated.above | indirect.above/total.above | 0.965 | (0.666 to 1.412) |

| Variables | Predictors | Label | B | SE | z | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INNO | SSCM | a1 | 0.583 | 0.234 | 2.498 | 0.012 | 0.533 |

| INNO | Education | a2 | 0.010 | 0.027 | 0.357 | 0.721 | 0.023 |

| INNO | SSCM:Education | a3 | −0.008 | 0.093 | −0.084 | 0.933 | −0.018 |

| SFP | SSCM | c | 0.016 | 0.079 | 0.199 | 0.843 | 0.015 |

| SFP | INNO | b1 | 0.477 | 0.182 | 2.627 | 0.009 | 0.496 |

| SFP | Education | b2 | −0.017 | 0.022 | −0.780 | 0.435 | −0.043 |

| SFP | INNO:Education | b3 | 0.086 | 0.073 | 1.170 | 0.242 | 0.227 |

| Effect | Equation | Estimate | 95% Bootstrap CI Boot.CI.Type = Perc |

|---|---|---|---|

| indirect | (a1+a3*Exp.mean)*(b1+b3*Exp.mean) | 0.366 | (0.247 to 0.505) |

| direct | c | 0.070 | (−0.080 to 0.233) |

| total | direct+indirect | 0.436 | (0.302 to 0.592) |

| prop.mediated | indirect/total | 0.840 | (0.551 to 1.241) |

| indirect.below | (a1+a3*(Exp.mean-sqrt(Exp.var)))*(b1+b3*(Exp.mean-sqrt(Exp.var))) | 0.486 | (0.284 to 0.689) |

| indirect.above | (a1+a3*(Exp.mean+sqrt(Exp.var)))*(b1+b3*(Exp.mean+sqrt(Exp.var))) | 0.262 | (0.145 to 0.415) |

| direct.below | c | 0.070 | (−0.080 to 0.233) |

| direct.above | c | 0.070 | (−0.080 to 0.233) |

| total.below | direct.below+indirect.below | 0.556 | (0.341 to 0.763) |

| total.above | direct.above+indirect.above | 0.332 | (0.177 to 0.504) |

| prop.mediated.below | indirect.below/total.below | 0.875 | (0.619 to 1.177) |

| prop.mediated.above | indirect.above/total.above | 0.790 | (0.435 to 1.339) |

| Variables | Predictors | Label | B | SE | z | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INNO | SSCM | a1 | 0.913 | 0.234 | 3.905 | <0.001 | 0.822 |

| INNO | Exp | a2 | 0.081 | 0.020 | 4.076 | <0.001 | 0.251 |

| INNO | SSCM:Exp | a3 | −0.103 | 0.067 | −1.542 | 0.123 | −0.305 |

| SFP | SSCM | c | 0.070 | 0.080 | 0.875 | 0.382 | 0.055 |

| SFP | INNO | b1 | 0.821 | 0.197 | 4.175 | <0.001 | 0.715 |

| SFP | Exp | b2 | 0.057 | 0.019 | 3.019 | 0.003 | 0.154 |

| SFP | INNO:Exp | b3 | −0.067 | 0.053 | −1.256 | 0.209 | −0.183 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharafuddin, M.A.; Madhavan, M.; Chaichana, T. The Effects of Innovation Adoption and Social Factors between Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Sustainable Firm Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159099

Sharafuddin MA, Madhavan M, Chaichana T. The Effects of Innovation Adoption and Social Factors between Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Sustainable Firm Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159099

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharafuddin, Mohammed Ali, Meena Madhavan, and Thanapong Chaichana. 2022. "The Effects of Innovation Adoption and Social Factors between Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Sustainable Firm Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159099

APA StyleSharafuddin, M. A., Madhavan, M., & Chaichana, T. (2022). The Effects of Innovation Adoption and Social Factors between Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Sustainable Firm Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability, 14(15), 9099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159099