Conservation and Management of Agricultural Landscapes through Expert-Supported Participatory Processes: The “Declarations of Public Interest” in an Italian Province

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Aims

2. Materials and Methods

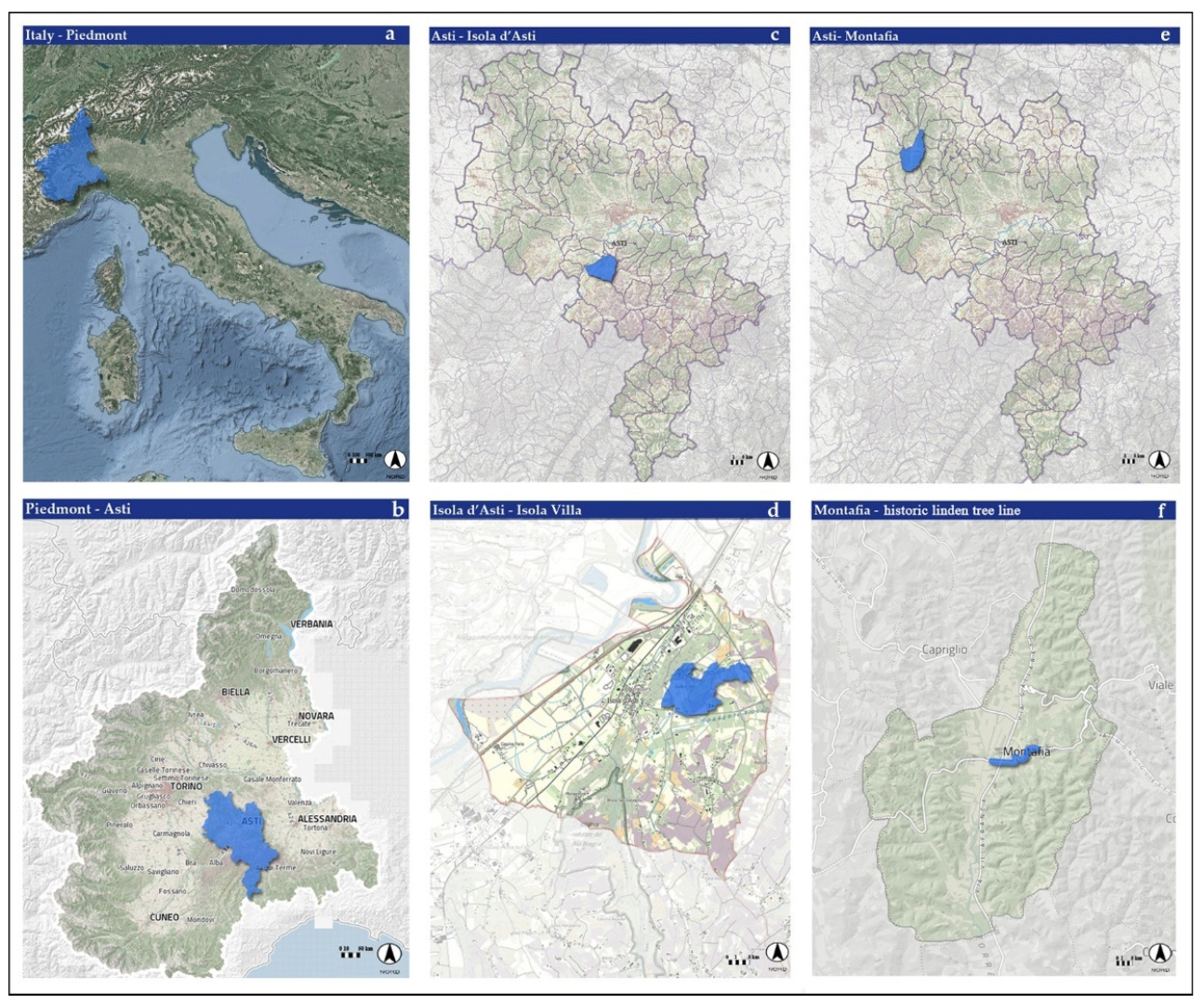

2.1. The Study Areas

- 1 Site of Regional Importance (the acronym of which is SIR in Italian) [12];

- 6 Sites of Community Importance (SCIs), including 1 Special Protection Area (SPA) and 5 Special Areas of Conservation (SACs); these are included in the European Union’s Natura 2000 Network [13];

- 1 nature park and 6 nature preserves;

2.2. Methodological Framework

Procedural Steps and Regulatory Framework

- “Immovable things of outstanding natural beauty, geological singularity or historical memory, including monumental trees” [19] (Art. 136, para 1.a);

- “The villas, gardens, and parks, … which stand out for their uncommon beauty” [19] (para 1.b);

- “Complexes of immovable things which constitute a characteristic aspect having aesthetic and traditional value, including historic centres and villages” [19] (para 1.c);

- “Beautiful views considered to be of picturesque quality as well as vantage points and belvederes which are accessible to the public and from which the spectacle of those beauties may be enjoyed” [19] (para 1.d).

2.3. Process Documentation: Methodology and Structuring

3. Results

3.1. The Process of Nominating the Landscape of Isola Villa as an Area of Public Interest

3.2. Relationships with Other Completed and Ongoing Case Studies: Linear and Single Assets, Homogeneous Regions, and Riparian Landscapes

3.2.1. Linear Assets: The Historical Tree Line of Montafia (Province of Asti)

3.2.2. Application in Progress

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Public Participation in Landscape Decisions

4.2. Community Engagement in Landscape Decisions

4.3. Declarations of Public Interest in Other Italian Regions and in Europe: A Comparison

- concerning Annexes A and B, the actual level of active involvement of citizenship within the existing regulatory framework in countries that are politically and administratively different from European ones [62];

- concerning Annex C.3, the diversity of approaches in spatial governance policies and the regulatory tools associated or associable with them.

4.4. Current Considerations in Land Development after the Promulgation of Declarations of Public Interest: Mayors and Municipal Administrators

- Q1.

- Do you feel that the landscape is a valuable asset to the municipality you govern? (Yes; no);

- Q2.

- If yes, for what reason? (Economic/tourist; economic/real estate; improving agricultural production; identity/cultural; other: please specify);

- Q3.

- In your opinion, does the Declaration of Public Interest of the landscape in your municipality reinforce the above reasons? (Yes; no);

- Q4.

- Years after the declaration was accepted and approved, how do you rate it? (Very good; good; fair; poor; very bad: please specify);

- Q5.

- When troubles arose, have they affected only villagers in their real estate asset management, the municipal government, or both? (Villagers; municipal government; both);

- Q6.

- When troubles arose, what were they specifically? (Bureaucratic complications/administrative burdens; increased costs in dossier preparation, submission, and management; longer timeframes for the start/execution of works; other: please specify);

- Q7.

- When confronted with any problems, do you think that more careful landscape management after the declaration has allowed and will allow protecting and sustaining the landscape qualities in your municipality, including for the benefit of future generations? (Yes; no; maybe. Please specify);

- Q8.

- Do you have any suggestions for improving administrative processes even in the presence of a protected landscape area related to the recognition of the public interest? (Simplification of administrative procedures in the local landscape committees; additional technical/administrative support from the Piedmont region; additional funding for these areas; other: please specify);

- Q9.

- Do you think that there might be other sites in your municipality that would merit recognition of public interest due to their landscape? (Yes; no. please specify);

- Q10.

- Would you advise other mayors to follow the same landscape conservation approach pioneered by the municipality under your administration in recent years? (Yes; no).

4.5. Current Considerations in Land Development after the Promulgation of Declarations of Public Interest: The Territory and Landscape Sector of the Piedmont Region

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perrotti, D. Studying the Metabolism of Resilient Communities: Urban Practices, Micronarratives, and Their Agency. In Resilient Communities and the Peccioli Charter, 1st ed.; Carta, M., Perbellini, M.R., Lara-Hernandez, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- ICCROM. People-Centred Approaches to the Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Living Heritage; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2015; Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/PCA_Annexe-2.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- ICOMOS. Resolution 20GA/19. People-Centred Approaches to Cultural Heritage. 2019. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Secretariat/2021/OCDIRBA/Resolution_20GA19_Peolple_Centred_Approaches_to_Cultural_Heritage.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Stenseke, M. Local participation in cultural landscape maintenance: Lessons from Sweden. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Aimar, F.; Chen, L. The joint force of bottom-up and top-down in the Preservation and Renewal of Rural Architectural Heritage, taking Piedmont, Italy as the case study. Jianzhushi 2021, 209, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Agnoletti, M. Landscape Perception and Public Participation for the Conservation and Valorization of Cultural Landscapes: The Case of the Cinque Terre and Porto Venere UNESCO Site. Land 2021, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treccani. Parchi Naturali. 1994. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/parchi-naturali_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/ (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Lange Vik, M. Self-mobilisation and lived landscape democracy: Local initiatives as democratic landscape practices. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arler, F.; Mellqvist, H. Landscape Democracy, Three Sets of Values, and the Connoisseur Method. Environ. Values 2015, 24, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.; Robertson, A.L. Landscape Conservation Cooperatives: Bridging Entities to Facilitate Adaptive Co-Governance of Social–Ecological Systems. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2012, 17, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.R.; Elmendorf, W.F.; McDonough, M.H.; Burban, L.L. Participation and Conflict: Lessons Learned from Community Forestry. J. For. 2005, 103, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regione Piemonte. Siti di Importanza Regionale (SIR). Dati Territoriali Comunali. 2020. Available online: http://giscartografia.csi.it/Parchi/sir_comuni_elenco.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Regione Piemonte. Risultato Ricerca Schede Siti di Importanza Comunitaria (SIC) in Piemonte. N.d. Available online: http://www.regione.piemonte.it/habiweb/ricercaSic.do (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- UNESCO. The Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato, Executive Summary, Nomination Format Book 1, Nomination Format Book 2, Management Plan. 2014. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1390rev.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- ISTAT. Resident Population on 1st January: Piemonte. 2022. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/?lang=en&SubSessionId=28f6b316-8c04-4ada-9c4d-4009a9d99fc5 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Comuni Italiani. Isola d’Asti—Redditi Irpef. 2015. Available online: http://www.comuni-italiani.it/005/059/statistiche/redditi.html (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Comuni Italiani. Montafia—Redditi Irpef. 2015. Available online: http://www.comuni-italiani.it/005/073/statistiche/redditi.html (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Republic of Italy. Constitution of the Italian Republic. 1947. Available online: https://www.senato.it/documenti/repository/istituzione/costituzione_inglese.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Italian Ministry for Culture. Legislative Decree no. 42 of 22 January 2004—Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage, pursuant to article 10 of law no. 137 of 6 July 2002. 2004. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/155711 (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Regione Piemonte. Legge Regionale 1 Dicembre 2008, n. 32. (Testo Coordinato). Provvedimenti Urgenti di Adeguamento al Decreto Legislativo 22 Gennaio 2004, n. 42 (Codice Dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio, ai Sensi dell’articolo 10 della Legge 6 Luglio 2002, n. 137). 2008. Available online: http://www.regione.piemonte.it/governo/bollettino/abbonati/2008/49/suppo2/00000004.htm (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Regione Piemonte. Documentazione di Riferimento per la Presentazione delle Richieste di Dichiarazione di Notevole Interesse Pubblico—D.lgs. 42/2004, Art. 137–140. 2011. Available online: https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/sites/default/files/media/documenti/2018-11/commissione_regionale_documento.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Council of Europe (CoE). European Landscape Convention. 2000. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680080621 (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Taylor, K. Cultural Landscapes and Asia: Reconciling International and Southeast Asian Regional Values. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N. Landscape, Landscape History, and Landscape Theory. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Europe, 1st ed.; Kockel, U., Craith, M.N., Frykman, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Taylor, K. Cultural landscape meanings. The case of West Lake, Hangzhou, China. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPRA. I Tipi e le Unità Fisiografiche di Paesaggio. n.d. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/servizi/sistema-carta-della-natura/carta-della-natura-alla-scala-1-250.000/i-tipi-e-le-unita-fisiografiche-di-paesaggio (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Landscape Perspectives. The Holistic Nature of Landscape, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, O. Landscape Theories. A Brief Introduction, 1st ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golobič, M. Transformation Processes of Alpine Landscapes and Policy Responses: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Views. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2018, 23, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.; Steen Jacobsen, J.K. Tourism smellscapes. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 5, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L.; Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Eye-tracking Analysis in Landscape Perception Research: Influence of Photograph Properties and Landscape Characteristics. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Yang, Y. Rural Soundscape: Acoustic Rurality? Evidence from Chinese Countryside. Prof. Geogr. 2021, 73, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, F.; Novelli, S.; Gullino, P.; Devecchi, M. Planning Rural Landscapes: A Participatory Approach to Analyse Future Scenarios in Monferrato Astigiano, Piedmont, Italy. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 707–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gullino, P.; Devecchi, M.; Larcher, F. How can different stakeholders contribute to rural landscape planning policy? The case study of Pralormo municipality (Italy). J. Rural Stud. 2018, 57, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimar, F.; Gullino, P.; Devecchi, M. Towards reconstructing rural landscapes: A case study of Italian Mongardino. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereni, E. Storia del Paesaggio Agrario Italiano, 1st ed.; Laterza: Bari, Italy, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Alomar-Garau, G.; Gómez-Zotano, J.; Arias-García, J. Teaching landscape in Spanish universities: Looking for new approaches in Geography. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isager, L.; Broge, N.H. Combining remote sensing and anthropology to trace historical land-use changes and facilitate better landscape management in a sub-watershed in North Thailand. Landsc. Res. 2007, 32, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A.; Eder, R. Exploring the Heterogeneity of Rural Landscape Preferences: An Image-Based Latent Class Approach. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaphorst, K.; Duchhart, I.; van der Knaap, W.; Roeleveld, G.; van den Brink, A. The semiotics of landscape design communication: Towards a critical visual research approach in landscape architecture. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, S.; van den Bosch, C.K.; Fu, W.; Qi, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, J. Does Adding Local Tree Elements into Dwellings Enhance Individuals’ Homesickness? Scenario-Visualisation for Developing Sustainable Rural Landscapes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Repetto, D.; Aimar, F. The Fifth Landscape: Art in the Contemporary Landscape. In Digital Draw Connections, 1st ed.; Bianconi, F., Filippucci, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Marraccini, E.; Lardon, S.; Rapey, H.; Debolini, M.; Benoît, M.; Thenail, C. Farming systems designing landscapes: Land management units at the interface between agronomy and geography. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2013, 113, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotchés-Ribalta, R.; Winsa, M.; Roberts, S.P.M.; Öckinger, E. Associations between plant and pollinator communities under grassland restoration respond mainly to landscape connectivity. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 2822–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josefsson, J.; Pärt, T.; Berg, Å.; Lokhorst, A.M.; Eggers, S. Landscape context and farm uptake limit effects of bird conservation in the Swedish Volunteer & Farmer Alliance. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 2719–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Diggelen, R.; Hobbs, R.J.; Miko, L. Landscape Ecology. In Restoration Ecology: The New Frontier, 1st ed.; van Andel, J., Aronson, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, H.S.K.; dos Anjos, L.H.C.; Xavier, P.A.M.; Chagas, C.S.; de Carvalho Junior, W. Quantitative pedology to evaluate a soil profile collection from the Brazilian semi-arid region. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2018, 35, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Graña, A.; Goy, J.; Zazo, C.; Silva, P.; Santos-Francés, F. Configuration and Evolution of the Landscape from the Geomorphological Map in the Natural Parks Batuecas-Quilamas (Central System, SW Salamanca, Spain). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, M. Landscapes and Literature: A Look at the Early Twentieth Century Rural South. J. Geog. 1998, 97, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raatz, L.; Bacchi, N.; Pirhofer-Walzl, K.; Glemnitz, M.; Müller, M.E.H.; Joshi, J.; Scherber, C. How much do we really lose? Yield losses in the proximity of natural landscape elements in agricultural landscapes. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 7838–7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Primdahl, J. Agricultural Landscape Sustainability under Pressure: Policy Developments and Landscape Change. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetta, G.; Caldarice, O. Spatial Resilience in Planning: Meanings, Challenges, and Perspectives for Urban Transition. In Sustainable Cities and Communities. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, 1st ed.; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voghera, A.; Aimar, F. Towards a definition of landscape resilience: The proactive role of communities in reinforcing the intrinsic resilience of landscapes. In Resilient Communities and the Peccioli Charter: Towards the Possibility of an Italian Charter for Resilient Communities, 1st ed.; Carta, M., Perbellini, M.R., Lara-Hernandez, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C. Landscape Resilience. Basics, Case Studies, Practical Recommendations, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musacchio, L.R. Landscape sustainability. In International Encyclopedia of Geography, 1st ed.; Richardson, D., Castree, N., Goodchild, M.F., Kobayashi, A., Liu, W., Marston, R.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe (CoE). Recommendation CM/Rec(2008)3 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Guidelines for the Implementation of the European Landscape Convention. 2008. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16802f80c9 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Devecchi, M. Gli Osservatori del paesaggio e la tutela dell’interesse pubblico del paesaggio. In Quaderni 15 “Paesaggio e Democrazia”, 1st ed.; Bonini, G., Pazzagli, R., Eds.; Edizioni Istituto Alcide Cervi: Gattatico, Italy, 2018; pp. 137–142. ISBN 978-88-941999-4-9. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Biggs, D.; Bohensky, E.L.; BurnSilver, S.; Cundill, G.; Dakos, V.; Daw, T.M.; Evans, L.S.; Kotschy, K.; et al. Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, M.L. Principles for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hauge Simonsen, S.; Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, M.; Bohensky, E.; Cundill, G.; Dakos, V.; Daw, T.; Kotschy, K.; Leitch, A.; et al. Applying Resilience Thinking. Seven Principles for Building Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. 2014. Available online: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/download/18.10119fc11455d3c557d6928/1459560241272/SRC+Applying+Resilience+final.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Devecchi, M. Forme di autogoverno nella pianificazione territoriale da parte delle comunità locali: Le Dichiarazioni di notevole interesse pubblico del paesaggio. In Territori e Comunità. Le Sfide Dell’autogoverno Comunitario, Proceedings of the VI Conference della Società dei Territorialisti, Castel del Monte, Italy, 15–17 November 2018; Gisotti, M.R., Rossi, M., Eds.; SdT Edizioni: Florence, Italy, 2020; pp. 90–98. ISBN 978-88-940261-8-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Q.; Aimar, F. How Are Historical Villages Changed? A Systematic Literature Review on European and Chinese Cultural Heritage Preservation Practices in Rural Areas. Land 2022, 11, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- République Française. Code de L’environnement. 2000. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/id/LEGITEXT000006074220/ (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- gov.uk. Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs): Designation and Management. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/areas-of-outstanding-natural-beauty-aonbs-designation-and-management (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Council of Europe (CoE). The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. Resolution 312 (2010)1—Landscape: A New Dimension of Public Territorial Action. 2010. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/landscape-a-new-dimension-of-public-territorial-action-rapporteurs-d-c/168071aeb7 (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Menatti, L. Landscape: From common good to human right. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 641–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe (CoE). Chart of Signatures and Ratifications of Treaty 176. 2021. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/176/signatures?module=signatures-by-treaty&treatynum=176 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Brunetta, G.; Voghera, A. Evaluating Landscape for Shared Values: Tools, Principles, and Methods. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Procedural Steps for Preparing Requests for Public Interest Structuring Analyses | |

|---|---|

| A | premises |

| a.1 | Establishing the rationale for requesting a Declaration of Public Interest. |

| a.2 | Identifying and studying existing national and regional conservation laws and policies. |

| a.3 | Identifying the proposing parties (e.g., cultural associations, foundations). |

| a.4 | Establishing the steps of administrative and procedural processing. Community inclusion through public meetings and assemblies, conventions, and open village/town meetings. |

| B | reasons for requesting preservation |

| b.1 | Designating proposed boundaries (included and excluded areas, and the logic for these). Drawing boundaries on a map: regional technical cartography, municipal plan Regulatory maps, cadastral maps and plans (depending on the type of boundary), and orthophotos. |

| b.2 | Details on the type of requested constraint, with reference to Art. 136 of Legislative Decree No. 42/2004 and subsequent amendments:

|

| b.3 | Summary indication of elements of excellence (e.g., rural systems, buildings of local interest, agricultural products). |

| C | territorial analyses |

| c.1 | Understanding the administrative organization (e.g., boundary identification at the municipal and Union of Municipalities levels). |

| c.2 | Identifying the physical features of the area (e.g., morphological, topographical). |

| c.3 | Describing the type of the area (e.g., urban, rural). |

| c.4 | Identifying the infrastructure axes (e.g., road and rail connections) that connect the nominated area. |

| c.5 | identifying and developing thematic cartography useful for the permitting process (e.g., religious hubs, high-value crops). |

| D | analysis phases and the layering of urban development |

| d.1 | Describing the main historical and evolutionary phases of existing settlement morphology (i.e., research in state and municipal archives, cadastral surveys). |

| d.2 | Synthesizing boards of the area under examination, starting with the first reliable sources. |

| E | interpreting historical maps and the components of the territory |

| e.1 | Researching, analysing, overlaying, comparing, and studying historical maps. Identifying historic routes, rural systems, historic settlements, toponymy, and buildings of local interest. |

| e.2 | Graphical comparison and summary boards. |

| F | physical features |

| f.1 | Natural ecosystems in the area under examination. |

| f.2 | Historical analysis (e.g., research in the state and municipal archives, historical land records) of food crops (17th and 18th centuries) and their evolution. Mapping current land uses (e.g., types of crops, meadows, and wooded areas). |

| f.3 | Valuable crop types mapping (i.e., PDO, PGI, TGI, CDO, and CGDO). |

| G | territorial register of assets of architectural and historic interest |

| g.1 | Scheduling of main assets of historic and architectural interest in the selected area. |

| H | analyses of the route system and tourist offer |

| h.1 | Analyses of the route system (e.g., bicycle trails, pedestrian and bridle paths) and itineraries (e.g., sightseeing, cultural, and spiritual) on a supralocal scale, with subsequent analysis of connections and potential criticality. |

| h.2 | Analysis of tourism facilities and farms. |

| h.3 | Item mapping (e.g., farms, accommodations) on current maps (i.e., regional technical maps). |

| I | the perception of the territory |

| i.1 | Photographic surveys with shooting points on current maps, both for the whole area and for the main assets related to it. |

| i.2 | Critical comparison of early 20th century photographs and postcards with current ones. |

| L | planning and preservation tools already in use |

| l.1 | Studying the Regional Landscape Plan. Analysis of guidelines, requirements, and regulations. |

| l.2 | Analysis of tourism facilities and farms. |

| M | active protection and enhancement proposals |

| m.1 | Proposals from the local community. Prescriptions proposed by the municipality. Proposing landscape-specific constraints and prescriptions that can be incorporated into the Municipal Regulatory Plan. |

| m.2 | Tourism promotion and agrifood promotion events already in place. |

| m.3 | Identifying promotion paths for each type of area (e.g., from trail enhancement projects to cultural events). |

| Start Date (Year) | Heritage Assets with Ongoing Procedures (Province of Asti) | Type of Assets |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Landscape of Mombercelli | Homogeneous landscape region |

| 2017 | Cave dwellings of Mombarone | Single |

| 2017 | River Tanaro riparian landscape | Riparian landscape |

| 2018 | Landscape of San Martino Alfieri | Homogeneous landscape region |

| Region | Piedmont |

|---|---|

| No. of Properties Listed as of Public Interest for Their Landscape | 8 |

| ANNEX A. Reasons for submitting the request General preamble on the reasons that led the applicant to prepare the request for the institution of landscape constraints; the request processing process; inputs and the potential level of sharing by the community and administrations concerned. | |

| ANNEX B. Reasons for protection Identification of the reasons for the application and excellence features of the assets/landscapes concerned that, in the applicant’s opinion, justify the imposition of the constraint and the Declaration of Public Interest; the proposed perimeter; and the areas excluded. Reference is made to letters a, b, c, and d of Article 136 of Legislative Decree 42/2004 about the type of property to be constrained: “single heritage assets”: immovable things, villas, and gardens (letters a and b); “territorial assets”: complexes of immovable things and scenic vistas (letters c and d). | |

| ANNEX C. General description of the property/area Description of the landscape elements characterizing the property/area submitted for constraint, focusing on the aspects related to the reasons for the application. The analyses should make it possible to know and appreciate the value and excellence elements and any other elements of degradation and criticality within the area under examination; they can be divided into the following subannexes: ANNEX C.1 Analysis of the proposed perimeter area, through the examination of the characterizing landscape elements of the following types: physical–natural, historical–cultural, urban settlement, perceptive identity. ANNEX C.2 Descriptive framing cartography referring to the analysis (as per point C.1) showing the basic landscape surveys carried out. Providing the descriptive cartography of the landscape context, which should allow the identification of the location and geography of the landscape area under consideration and represent the places graphically and synthetically identified from the analysis referred to in point C.1. ANNEX C.3 Analysis of the safeguarding tools and territorial/urban planning provisions already operating in the landscape context and in the area under submission. Framework of the property/area under consideration in the current territorial, landscape, and urban planning system (through consultation of the PTR, approved PPR, PTCP, PRGC, and any other existing/adopted planning tools, of which cartography excerpts and implementation rules can be prepared). ANNEX C.4 Photographic shots of the assets and areas included within the proposed perimeter, indicating the snapshot positions on a suitable planimetry. This documentation should consist of panoramic and overall views (as well as detailed ones) to describe the context and features of the places and the landscape values motivating the request for the Declaration of Public Interest. Attention should be paid to the existing intervisibility relationships concerning the main viewpoints. This corpus may usefully be referred to as the descriptive cartography analysis of the landscape area under examination (C.2) to facilitate the understanding of the places. | |

| ANNEX D. Planimetry Drawn up on a scale suitable for the unambiguous identification of the properties and areas under the declaration request. It should be accompanied by any cadastral extracts central to the definition of the perimeter and a detailed description of the proposed boundary. For “territorial assets” (letters c and d of Art. 136), the perimeter should be reported on CTR (scale 1:10,000). | |

| ANNEX E. Proposals for prescriptions for use Prescriptions, design solutions, and guidelines aimed at enhancing the valuable elements recognized by the analysis and/or at resolving the main critical issues highlighted, developed, and shared by the communities/administrations and by the subjects involved based on their own specific and direct knowledge of the area’s landscapes. | |

| Region | Marche |

|---|---|

| No. of Properties Listed as of Public Interest for Their Landscape | 2 |

| ANNEX 1. Description of the area and reasons for the proposed protection (landscape constraint) General preamble on the reasons that led the applicant to formulate the request for the institution of landscape constraints; description of the elements to be protected and preserved. In particular, reference to letters a, b, c, and d of Art. 136 of Legislative Decree 42/2004 in relation to the type of asset to be constrained: “single heritage assets”: immovable things, villas and gardens (letters a and b); “territorial assets”: complexes of immovable things and scenic vistas (letters c and d). | |

| ANNEX 2. Description of cartographic perimeter to be constrained Perimeter of the area on current cartography (regional technical map, cadastral map with identification of the affected land parcels). | |

| ANNEX 3. Photographic records Photographic shots of the assets and areas included within the proposed perimeter, indicating the snapshot positions on a suitable planimetry. This documentation should consist of panoramic and overview views. | |

| ANNEX 4. Description of outstanding elements Description of the landscape elements characterizing the property/area under the request for constraint, investigating the reasons for the constraint. Analysis of the landscape context and the proposed perimeter area, through the examination of the characterizing landscape elements of the following types: botanical–vegetation elements; historical–cultural settlement elements; and identity elements. | |

| ANNEX 5. Rules of use Analysis of the existing safeguarding tools and territorial/urban planning provisions in the landscape context and in the area. Use of prescriptions, design solutions, guidelines aimed at the valorization of the outstanding elements. | |

| Region | Veneto |

|---|---|

| No. of Properties Listed as of Public Interest for Their Landscape | 9 |

| No minimum required documentation is indicated. Reference is made only to Article 138 of Legislative Decree No. 42/2004 Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage of the Italian State: “The recommendation shall include the grounds for the aforesaid declaration with reference to the historical, cultural, natural, morphological and aesthetic characteristics belonging to the immovable properties and areas which have identifying significance and value for the territory in which they are located and which are perceived as such by the population.” | |

| Region | Lombardy |

|---|---|

| No. of Properties Listed as of Public Interest for Their Landscape | 4 |

| No minimum required documentation is indicated. Reference is made only to Article 138 of Legislative Decree No. 42/2004 Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage of the Italian State: “The recommendation shall include the grounds for the aforesaid declaration with reference to the historical, cultural, natural, morphological and aesthetic characteristics belonging to the immovable properties and areas which have identifying significance and value for the territory in which they are located and which are perceived as such by the population.” | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aimar, F.; Cavagnino, F.; Devecchi, M. Conservation and Management of Agricultural Landscapes through Expert-Supported Participatory Processes: The “Declarations of Public Interest” in an Italian Province. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148843

Aimar F, Cavagnino F, Devecchi M. Conservation and Management of Agricultural Landscapes through Expert-Supported Participatory Processes: The “Declarations of Public Interest” in an Italian Province. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148843

Chicago/Turabian StyleAimar, Fabrizio, Francesca Cavagnino, and Marco Devecchi. 2022. "Conservation and Management of Agricultural Landscapes through Expert-Supported Participatory Processes: The “Declarations of Public Interest” in an Italian Province" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148843

APA StyleAimar, F., Cavagnino, F., & Devecchi, M. (2022). Conservation and Management of Agricultural Landscapes through Expert-Supported Participatory Processes: The “Declarations of Public Interest” in an Italian Province. Sustainability, 14(14), 8843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148843