1. Theoretical Background

Internal relational capital refers to a company’s intellectual property, work processes and techniques, executive procedures, databases, communication and information infrastructure, and so on. Employee relations and leadership activities become pivotal in this context. All company employees may increase the chances of success by performing deliberate and systematic actions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The organization can create synergistic effects thanks to staff expertise and internal collaboration. Internal relations in modern businesses should be improved, both with employees and among them [

4,

5,

6]. According to social capital theory, when people sustain connections with others and repeatedly act together to achieve shared goals, it leads to lasting benefits for individuals and strengthens the bonds between them [

7]. Corporate social capital is a category resulting from participation in a network of relationships which grants the participants access to the resources of cooperating enterprises and those jointly produced on the basis of shared norms, principles, values, and trust. Consequently, this promotes improved operational efficiency and builds competitive advantage [

7,

8]. Building internal networks of dependencies and relationships helps in the execution of formal structures, allows for creative and inventive thinking, encourages knowledge transfer, and promotes corporate circumstances to gain agility and flexibility, which translates into the formation of external relationships, improves efficiency, and allows a company to survive and develop in a changing environment [

5].

The creation of relational capital is an immanent feature of every organization, which is an open system that permanently exchanges tangible and intangible resources with the environment [

3,

9]. Conscious and methodical actions of employees at all organizational levels in the context of creating proper inter-organizational relations increase the probability of market success. Valuable organizational knowledge lies in the ability to leverage relationships in a way that helps build lasting business relationships in which business partners seek to work with each other. With the knowledge of the employees, and through their cooperation, a company can achieve synergies. The ability of human capital to create a significant and sustainable competitive advantage is due to its specific characteristics (qualitative nature, uniqueness and inimitability, innate ability to generate value, development in the long term, mobility) [

10]. This capital has the capacity to multiply its value (e.g., through employee learning and use of knowledge) [

11,

12]. The remaining resources of the enterprise increase their value only as a result of their appropriate use; therefore, the creation and development of human capital is an important area of building the potential for competitiveness of modern organizations [

13]. Human capital includes the education, abilities, knowledge, experiences of employees, their capabilities to develop innovative solutions, and the creativity of members of an organization. Internal structural capital is the intellectual property of an organization, work processes and methods, procedures, databases, and communication and information infrastructure. External structural capital comprises the structures used to maintain proper relationships with the environment. A company establishes relationships and interactions with and among its employees (internal architecture), with its suppliers or customers (external architecture), or within a group of companies engaged in related activities. More and more often, organizations adopt the strategy of creating and improving the relational capital both in the internal perspective and with the organization’s environment as part of building the philosophy of business operation [

4,

7,

14].

The literature has identified key areas of Positive Organizational Potential (POP): corporate governance, leadership, middle managers, talent management, interpersonal relationships, trust, internal communication language, citizenship behavior, and corporate social responsibility [

15]. Numerous studies and extensive subject literature offer deep insights into leadership and its effect on the success of an organization [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], as well as its sustainable development [

21]. Review studies, mostly using the systematic literature review method [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], explore the individual aspects associated with the importance of characteristics of modern leaders, and the effectiveness of various leadership styles. Moreover, in the literature on the management subject, one can find research results indicating the importance of human and social capital as a key factor for the company, often constituting a significant source of competitive advantage and strengthening the company’s position in relation to market rivals in shaping the competitive advantage of enterprises [

28]. However, there is a gap in the identification of mechanisms for a company to communicate with workers that would foster the improvement of its relational capital. The role of leadership in creating positive organizational potential is also overlooked. One of the goals of the planned research is to fill this identified research gap.

The presented concepts contain both the narrow and the wide approach to understanding relational capital. In a narrow sense, it consists of relations with customers, while in a broader sense, it includes relations with both external and internal entities. Therefore, it seems that the essence of this capital is formed by a company’s ties with its stakeholders and its partners’ satisfaction from cooperation with the company and loyalty to it. The concept of relational capital is closely related to the concept of social capital [

29]. Social capital derives from the network of relationships that connect people within an organization. P. Bourdieu defines social capital as the resources associated with participation in durable networks of interconnections with varying degrees of formalization [

30]. It includes complex and multi-element categories based on networks of relationships [

31]. According to social capital theory, when people sustain connections with others and repeatedly act together to achieve shared goals, it leads to lasting benefits for individuals and strengthens the bonds between them [

32]. Corporate social capital is a category resulting from participation in a network of relationships which grants the participants access to the resources of cooperating enterprises and those jointly produced on the basis of shared norms, principles, values, and trust. Researchers’ findings include the impact of positive interpersonal relationships among employees on effective knowledge management [

33] and higher job performance [

34], or the importance of positive leadership on employee motivation and engagement [

35], as well as on the success of organizations and their sustainable performance [

36,

37]. Consequently, this promotes improved operational efficiency and builds competitive advantage. Despite the diversity of approaches to social capital, we can distinguish some common features pointing to the essence of this capital and its connection with relational capital, i.e., cooperation, trust, and information sharing. As a result, the purpose of this study is to outline methods for improving internal relations in the enterprise. This article shows which activities were undertaken in companies to foster relations within the organization according to managers, and to what extent certain activities fostered positive relationships between employees and the company and what was their importance to the employees.

2. Materials and Methods

The study is a component of a larger research effort on the role of relational abilities in the creation of organizational value. Leadership and communication play important roles in managing relationships with the environment. One of the study project’s specific goals was to examine the function of a leader in the process of building and strengthening intellectual capital. The research, which took place between 2018 and 2020, focused on the relevance of relationship skills in building organizational value and in leadership. The research is based on data from ten significant international corporations. The businesses were chosen for their industry leadership and significant potential for innovation. Only a few companies were included in the study due to the nature of the research. Furthermore, the businesses were chosen for their potential to develop relational competencies. The research instruments employed in the investigations were quite detailed, allowing for an in-depth study. The purpose was to gather enough information to conduct a thorough examination of the role of relational competences in building the company value and their importance for leadership. As previously mentioned, the research findings presented here are part of a larger study. The questions addressed, among other things, the identification of problems associated with communication in the processes of building relationships between a company and its environment, tools and methods of communication in the processes of knowledge transfer between stakeholders, the role of leadership in the process of creating and improving intellectual capital, as well as identification factors and methods of improving internal relations in the context of building intellectual capital, and their impact on links with the environment. In the questionnaire, we used a Likert scale from 1 to 5, which were assigned appropriate descriptions. This made it possible to indicate with what strength the respondent agrees or disagrees with a given statement.

The research was conducted with two groups of respondents. The first group consisted of managers—the respondents were top executives: board presidents and directors (N = 10). The companies questioned were mostly manufacturers and service providers who represented prospective business areas and operated on a global scale. The information was gathered by personal interviews. The study instrument was a personal survey questionnaire, and the respondents were management staff members of analyzed companies. The sample was not representative, and therefore, the results cannot be generalized to the entire population of enterprises. The selection of enterprises was deliberate here due to their industry leadership, significant potential for innovation, and potential for developing relational competencies.

In the second stage of the project, an additional survey was conducted on the studied topic, which this time included the employees (

N = 185) of the analyzed companies. The workers of the assessed enterprises—which had a large employee population, more than 250 people—could not be overlooked when deciding the size of the study sample. The measuring technique in this case was an online questionnaire. The poll was conducted among the employees of the investigated businesses, regardless of their role, professional experience, or education. In this study, a 50% share of the phenomenon in the population was assumed. The size of the surveyed population of employees of the surveyed enterprises was nearly 30,000 people. It was found that the satisfaction would be with 95% certainty that the result obtained in the research did not differ from the actual value in the population by more than 10%. Using the formula [

38], the minimum sample size was set at 96 employees.

where:

n—Sample size;

N—Size of the studied population;

p—Percentage share of the phenomenon in the population;

q = 1 − p;

Zα—The value of the mean standard error, read from the tables, for the confidence level 1 − α; and

e—Admissible error of estimate.

The selection of employees for the sample was random. Each employee could complete the questionnaire. Ultimately, 185 questionnaires were obtained, which meant that the permissible error of estimation decreased from 10% to 7.2%.

Based on structural indicators reported as percentage values, the gathered data were utilized to perform a structural analysis. Furthermore, cluster analysis was utilized to examine the consistency (similarity) of the respondents’ ratings. Cluster analysis was used to show differences in opinions of respondents’ groups. Surveying a group of purposively selected innovative companies, we wanted to know the opinions of managers and employees. The primary goal of cluster analysis is to find natural groupings of entities (clusters) [

39]. This approach is used to find clusters of comparable items that are characterized by more than one characteristic. It is used to gain a thorough, non-simplified view of an object’s structural similarities. Ward’s approach was used as an agglomerative method to merge clusters in order to generate highly homogenous groupings. It is permissible in the context of the investigated problem to produce fewer clusters of items or clusters of equal size, but with minimum internal variation and representing the true structure. The Euclidean distance was utilized as a unit of measurement. In the case of the cluster analysis conducted for the 10 surveyed companies, it should be noted that their size is not sufficient to infer the entire population of companies, so the results cannot be generalized. At the same time, the number of surveyed companies is sufficient to show the differences in the perception of the studied ways of building internal relational capital by managers and employees. As already mentioned, cluster analysis was performed using Ward’s method, which uses the analysis of variance approach to estimate the distance between clusters. So, it aims to minimize the sum of squares of deviations of any two clusters that can be formed at any stage. It is treated as efficient, aiming to form clusters of a small size.

3. Results

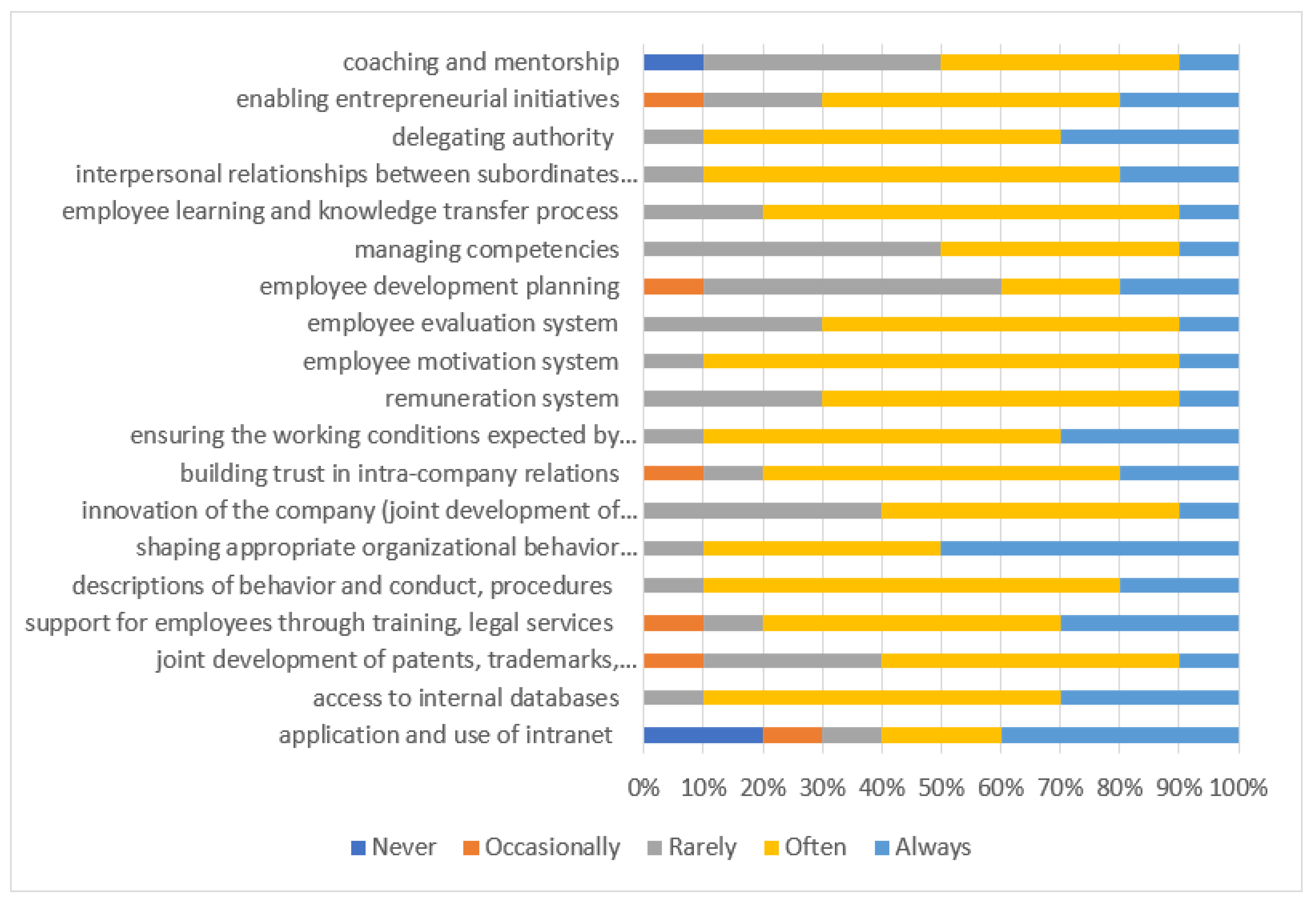

The first survey included questions about building relationships between the company and its employees. Based on the literary sources studied, a list of 19 such measures was compiled, and the respondents could specify another measure taken by their company. The results are presented in

Figure 1.

As the data on the frequency of application of the indicated solutions show, respondents have experience in applying the proposed activities of building relationships with employees. Only in the case of coaching and mentoring and the application and use of the intranet in individual cases were they not used. Most respondents admitted that they used most of the proposed solutions frequently. The interpersonal relationship between the subordinate and the supervisor was clearly noticeable. The importance of an incentive system along with the provision of expected working conditions was emphasized equally as often. Forming appropriate organizational behaviors, descriptions of behavior and conduct, and clearly defined procedures were also conducive to building relationships. The surveyed companies indicated frequent use of internal databases in the communication process and delegation of authority. Employee learning and the internal knowledge flow between employees frequently occurred in the majority of the companies surveyed. What was surprising, however, was that two of the large companies surveyed indicated that learning and knowledge transfer rarely took place in their companies. Interestingly, two other large companies surveyed never used an intranet, and only one always collaborated with employees to develop patents, trademarks, copyrights, or computer programs. Employee development planning and competence management were assessed the lowest in the surveyed companies; as many as 50% of respondents admitted these measures were rarely applied in their companies.

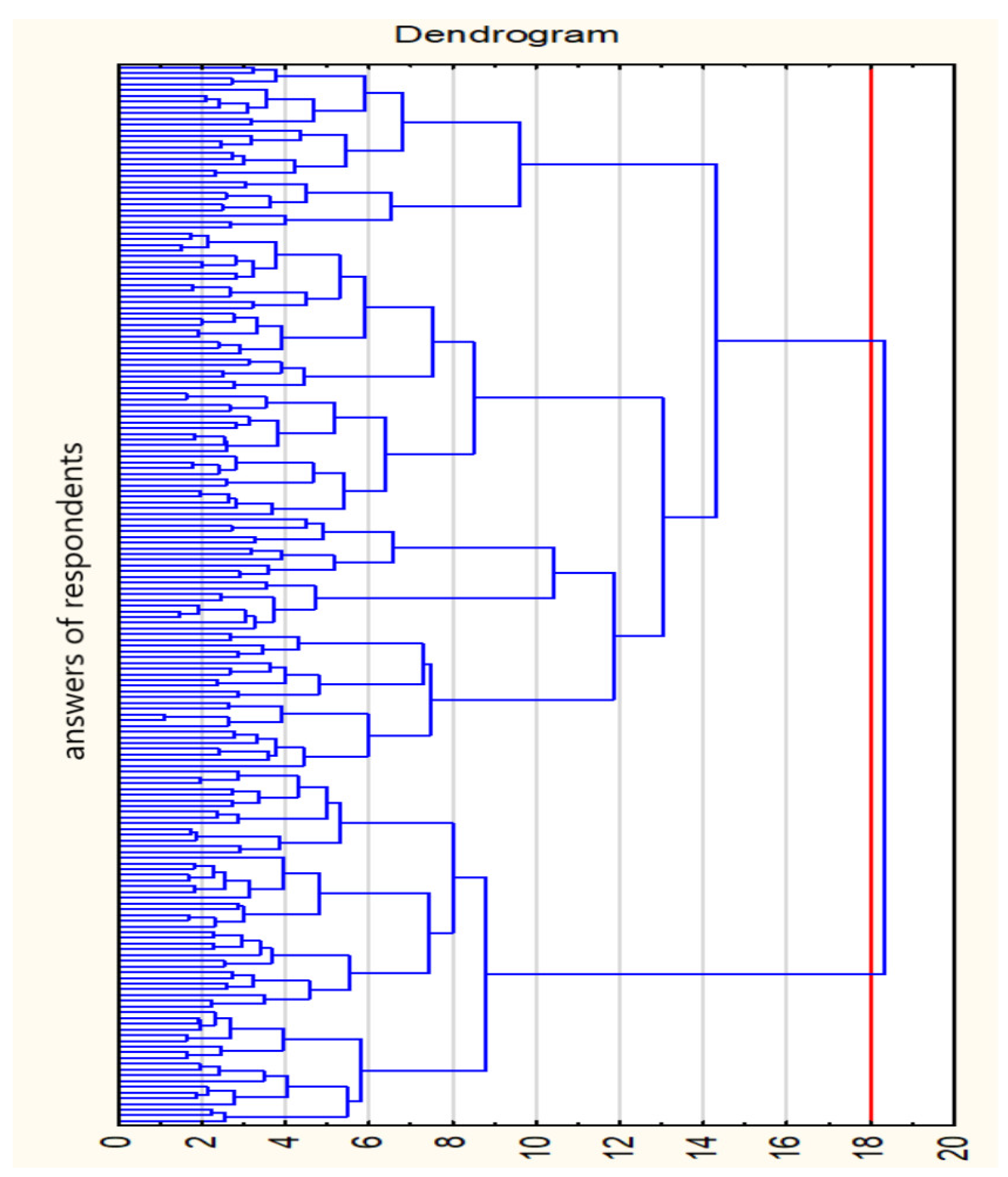

For a more in-depth assessment, we applied cluster analysis to determine how near or far the investigated firms are in terms of the relevance of the metrics for creating relationships between the company and its employees. It is depicted graphically as a dendrogram displaying clusters based on managers’ opinions and demonstrating cluster hierarchy (

Figure 2).

These methods identified one cluster. As a consequence, the desired outcome, i.e., a single cluster encompassing all of the investigated items, was obtained. It implies that the managers were unanimous in their opinion of the significance and implementation of the supplied indicators in their organizations. For a more detailed characterization of cluster, the average values was determined from each measures.

Table 1 presents the obtained results.

In the second study, the roles were reversed and the employees of the surveyed companies were asked to what extent certain activities fostered positive relationships between employees and the company (management) and what their importance is to the employees. The results are presented in

Figure 3.

As can be seen from the data presented in

Figure 3, the remuneration system, as a basic element of the motivation system, was most conducive to building positive relationships between employees and the company. In addition, relationships within the company should be based on trust. Employees should also have the opportunity to take entrepreneurial initiatives. The least important were IT-related activities, i.e., access to internal databases or the use and application of the intranet. This seems reasonable, as interpersonal communication is essential to building positive relationships. The results confirm the necessity of creating mechanisms in companies that help reconcile the realization of individual needs of employees with the purpose of the organization. It is undeniable that the basic needs that are satisfied by professional work are material stability and obtaining additional payments for undertaking increased effort. The need for stability is also revealed in relation to trust. Employees have an unequivocal preference for forming relationships that are underpinned by trust.

The data received from the workers were then subjected to cluster analysis, shown graphically on a dendrogram that depicts the cluster hierarchy (

Figure 4). The branches of the dendrogram grow noticeably longer at some point, indicating their cut-off points and the end of grouping. A cut-off point for the branches was established using the agglomeration curve and the critical distance value (shown by the red line on the dendrogram).

Two clusters were discovered using these approaches. As a result, the desired outcome, i.e., a single cluster encompassing all of the investigated items, was not obtained. This implies that workers differed in their appraisal of the value of the supplied indicators for the development of connections between the firm and its employees. The first cluster comprises 123 respondents and the second one has 62 respondents. The obtained cluster profiles indicate that the respondents from the second cluster rated the importance of activities for building relations between the company and its employees much higher than the other employees of the analyzed companies. Most of the respondents representing the first cluster rated most of the analyzed activities at a moderate level. Their evaluations of individual activities, on the other hand, were below the overall average. The results are presented in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

The results show which activities were undertaken in companies to foster relations within the organization according to managers, to what extent certain activities fostered positive relationships between employees and the company, and what their importance was to the employees. The study results support the following conclusions. It is not uncommon for the surveyed enterprises to undertake measures to enhance their internal relations. However, the assessment of the measures implemented for the improvement of the internal relationships varies between the studied groups: managers assign them differently than do employees. From the point of view of managers, interpersonal relationships between subordinates and supervisors was clearly noticeable. The importance of an incentive system along with the provision of expected working conditions was emphasized equally as often. Forming appropriate organizational behaviors, descriptions of behavior and conduct, and clearly defined procedures were also conducive to building relationships. From the point of view of employees, the remuneration system as a basic element of the motivation system was most conducive to building positive relationships between employees and the company. In addition, relationships within the company should be based on trust. Employees should also have the opportunity to take entrepreneurial initiatives.

Significant differences between the groups are the most prominent in the assessment of “shaping appropriate organizational behavior (organizational culture)”, “descriptions of behavior and conduct, procedures”, and “access to internal databases”; managers assigned much more meaning to these measures compared to employees. Cluster analysis revealed that managers’ views of the importance and implementation of the provided measures in their organizations were consistent, whereas employees’ perceptions of the researched phenomena were not. All surveyed managers were unanimous in their opinion of the significance and implementation of the supplied indicators in their organizations. Workers differed in their appraisal of the value of the supplied indicators for the development of connections between the firm and its employees. The employees in the most numerous cluster assessed the importance of measures for the improvement of the internal relationships at a moderate level, and the employees in the less numerous but strong cluster assessed them much higher than the other employees of the analyzed companies.

Based on the obtained results, it can be concluded that it is not unusual for the queried companies to take action to improve internal relations. However, the evaluation of the implemented initiatives for the improvement of internal relationships varies among the studied groups. Cluster analysis revealed that managers’ views of the importance and implementation of the provided measures in their organizations were consistent, whereas employees’ perceptions of the researched phenomena were not. This might imply that the importance of the presented measures for the improvement of internal relational capital is perceived differently by employees. This research could direct firms on the right path when it comes to developing internal relationships. The findings may prompt reflection of the company’s attempts to increase its relational capital if they are well implemented, provide the expected effects, and are assessed similarly by employees and management.

Most authors agree that human capital plays a key role in contemporary enterprises [

40,

41]. Human capital entails individual potentials of the participants of an organization, in the form of physical, mental, intellectual, and moral characteristics, shaped by predispositions, talents, knowledge, skills, motivation, health, and vital energy resources, which underline the functioning and development of individuals. A company’s value, uniqueness, and stability are important factors in the process of building its competitive advantage. Aspects that gain particular importance in a knowledge-based economy are creativity and innovation that determine the ease of adaptation to operating in a turbulent environment. There is a problem with permanently linking human capital to an organization, as it is not owned by the business, but only linked to it in free networks and partnerships [

42,

43].

In the conditions of knowledge-based economy, human capital is the basic strategic resource of an enterprise that underpins the effectiveness of modern management. A variety of sources demonstrate that financial compensation is a priority to the employee in the decision-making stage of seeking and entering employment. However, the stimulating effect of monetary compensation is limited by many subjective factors [

44]. In unstable conditions, when employees are uncertain about their future, motivation to work decreases and financial incentive instruments do not work sufficiently. In such a situation, it is all the more important to build the engagement of employees in increasing the value of the company by strengthening their knowledge competence and, consequently, building the potential of the entire company. The Internet of Things is becoming a concept that shapes modern business models. It is particularly realized in the energy sector, for example, through smart homes or smart grids. The implementation of this concept into the ways of managing the enterprise, its services, and its products requires the ability to manage internal relations in the enterprise. The companies face the challenge of digitization. The products and services offered should be better suited to the needs of customers, focused on the effective operation of devices. Data collection and analysis are inextricably linked to access to this information and the delegation of powers, indicated as among the most important in terms of building internal relations between employees and the company. Data collection is expensive, but necessary to enrich the sales service with consultancy. Feedback from the customer and its analysis will allow for better management of knowledge about the customer. Automation and digitization as well as data analysis require the creation of strong relationships between employees and the company, which will increase the quality of services provided and savings for the customer [

45,

46].

The essence of this phenomenon allows us to conclude that the key determinant of engagement is the ability of the employee to dispose of the resources assigned to them in an independent manner, which in turn determines the innovativeness of their actions. It is important to note, however, that the scope of innovative activities now extends beyond the boundaries of product and its enhancements. This is because it increasingly covers processes, implemented concepts, and other organizational changes that foster business improvement. An employee who is engaged in their work identifies with the company, seeks challenges and realization of his/her professional ambitions, fulfills his/her duties, thinks innovatively, and takes actions that will serve to improve the competitiveness of the entire organization. Experiencing such a state should be intrinsically satisfying [

47,

48]. Taking this into account, work engagement is a positive approach to responsibilities, a full interest and preoccupation that is characterized by dedication to pursuing additional activities beyond formally defined responsibilities [

48,

49]. In addition, employee engagement requires a shift away from the relationship of dependency that exists between employer and employee to one of equality, where responsibility is bilateral. This is because employee engagement is rooted in positive attitudes towards their superiors and a sense of responsibility for the results of their own work. It is now recognized that people go beyond the traditional understanding of work, which is treated not only as a source of income, but as a place to pursue one’s own developmental goals and aspirations and a place where one can affirm one’s self-worth. This is fostered by deep company revitalization, which can be viewed as a key determinant of building employee engagement. It involves taking strategic action at the general level, building a new organizational culture, innovative methods of communication, new values, and creating the foundations for employee initiatives [

50].

Interest in employee commitment stems from perceived consequences for organizations ranging from employee behavior (turnover, job satisfaction, or citizenship behavior) to the relationship between employee commitment levels and company performance: increased employee commitment leads to improved customer satisfaction, increased revenue, and an improved competitive position [

15]. The indicated connections push the organization to take actions to increase employee commitment, and thus it becomes important to learn about the conditions of this specific relationship between the employee and the company [

51]. The engagement of employees in building the potential of the company can be an important source of competitive advantage of modern companies, thanks to the acquisition of new knowledge, both explicit (formal) and implicit (tacit). Several significant challenges should be noted in the context of the energy sector. Not just for good firm management, but also for energy transformation and the transition to low-carbon technologies, understanding the traits and style of leadership is critical. In truth, the key question is how to control this without causing considerable social friction and with the greatest benefit to local communities [

52]. This mostly refers to the ability to deal with the complexities of environmental challenges and mobilize organizations to carry out a long-term ecological balancing vision. It also plays a critical role in comprehending and responding to the demands of a diverse variety of stakeholders, as well as fundamentally transforming organizational processes [

10,

53]. Furthermore, in the energy sector’s transformation, leaders should establish intra-organizational relationships in order to launch bottom-up—usually emergent and informal—initiatives, which should include a network of leaders and change agents [

54].

Building an emotional bond with an employee is a two-way relationship; hence, the organization cannot just expect a high level of employee engagement, but should actively shape the mutual relationship, which consists of a sequence of interactions that are expressed in the actions of both entities. According to E. Deming, leaders must be aware of the fact that they should create conditions stimulating the development of creativity in employees. This way, subordinates will be able to reveal their skills and propose innovative changes in the company [

55]. A leader’s job is to create an environment in which employees may excel in their jobs and continually improve their performance. To this end, it is critical for leaders to learn everything there is to know about each member of the team and to show that they care about their job in order to develop trust and help employees attain their maximum potential [

11]. The leader’s job is also to build an effective and responsible team with members who are in sync with one another and can work together to achieve company objectives. As a result, the leader must be able to balance company and employee interests [

4,

12,

56].

Nowadays, as companies are in constant pursuit of more and more ambitious goals with rapid technological advancements and high expectations of specialist employees, the role of the leader in building the social potential of a company is paramount. A competent leader, while facing a host of obstacles, will be able to create an optimal work environment for employees to fulfill their tasks and for the company to grow. It is therefore crucial for a manager to provide employees with compulsory training opportunities, as well as propose additional training that supports the process of employee self-education and self-fulfillment. Thanks to the specialist skills gained in the workplace while spending time learning and gaining experience, the employee identifies with the company and feels good, because they are aware that their knowledge is essential for the company [

12]. Effective environmental leadership should inspire effective and efficient actions to transform the way goods are produced, processed, distributed, used, and managed in this context. A leader’s personality can determine a project’s success, and leadership’s purpose is to foster strong relationships, facilitate successful teamwork, increase morale, empower, and inspire individuals [

57].