5.1. Hypothesis Findings

The findings show that authentic leadership positively impacts employees’ trust in leaders and the organization. Effective leaders need to earn the employees’ trust, which is an essential construct of social exchange theory [

98]. Mayer et al. [

29] argued that trustworthy leaders require ability, benevolence, and integrity as essential characteristics. This leadership style motivates employees’ positive attitudes and behaviors, leading to job satisfaction, trust, and better performance [

24]. Hassan and Ahamed [

99] also indicated that authentic leaders show a high degree of integrity, focus on their purpose, and commit to their core values. Consequently, this stimulates more trusting relationships among people, leading to positive outcomes for work engagement. Moreover, trust mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and employee work engagement. People believe that the best place to work is where they can trust the leaders and teams and feel enthusiastic about working with them. Farid et al. [

100] indicated that authentic leadership promotes a higher level of cognitive-based and affective-based trust; it also has a positive relationship with organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). Coxen et al. [

76] reported that authentic leadership motivates organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) through trust and influences a culture of trust in the workplace. Iqbal et al. [

79] firmly stated that authentic leadership has a positive influence on both affective-based and cognitive-based trust, and moreover, that both positively mediate the relationship between authentic leadership and OCBs. Authentic leaders always show their true selves to their followers; as a result, they can encourage their followers to trust them and the organization, which is conducive to better cooperation and teamwork [

39]. Employees trust leaders based on their actions and character [

26]. Thus, authentic leadership positively impacts trust [

25].

Avolio and Gardner [

36] stated that this leadership style positively affects employees’ social exchange relationships. Authentic leaders develop positive emotions and social exchange relationships in organizational culture. Leaders’ and followers’ positive psychological capacities, confidence, optimism, resiliency, and hope can be improved by authentic leadership. Additionally, this kind of leadership strengthens employees’ self-awareness and self-regulation, leading to a process of positive self-development. Leaders’ positive attitudes and skills motivate collaboration, employee commitment, and high-quality social exchange relationships [

45]. The leadership role is essential for shaping quality social exchange relationships [

101]. Therefore, leaders with competency, authenticity, and honesty are the appropriate partners for employees to engage in social exchange relationships [

35]. At the same time, it is the leaders’ duty to establish a conducive environment by building a transparent relationship with organizational members, enhancing good communication within the organization, which leads to sustainable management. A healthy social exchange relationship among team leaders and members can help employees accomplish organizational goals [

28]. This implies that authentic leadership positively influences a high level of social exchange relationships between leaders and followers, leading to high work engagement of employees because this relationship motivates their perception, attitudes, and behaviors [

102]. Therefore, setting the social exchange relationship as a mediator can induce a positive relationship between authentic leadership and employee work engagement that can bring about sustainable integration within companies. Moreover, the interaction between authentic leadership and high-power distance of employees induces a strong social exchange relationship between leaders and members [

102].

According to Blau [

98], trust has a direct effect on social exchange relationships, since trust is a fundamental element in this kind of relationship, which spotlights feelings and obligations. When someone does a favor for another, they expect to receive some return benefit in the future [

17]; therefore, trust is required, implying that trust is essential for maintaining a social exchange relationship. Trust and macromotives, e.g., commitment and loyalty, form the basis of a social exchange relationship that characterizes the feelings and beliefs of partners about each other [

89,

98]. On the one hand, trust, mutual commitment, and loyalty have a direct impact on high-quality social exchange relationships [

11]. A social exchange relationship is a two-way arrangement, with giving away and giving back. Therefore, one party’s behavior will affect the other party; thus, interdependence between parties can decrease the risk of poorly cooperative relationships and promote cooperative behaviors [

11]. Moreover, based on social exchange theory, partners’ trustworthiness increases trust and commitment under the risk condition and uncertainty of the exchange situation [

22]. Konovsky and Pugh [

78] indicated that procedural justice can improve employees’ trust in their leaders. Trust in leaders can mediate the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behaviors, leading to high-quality social exchange relationships.

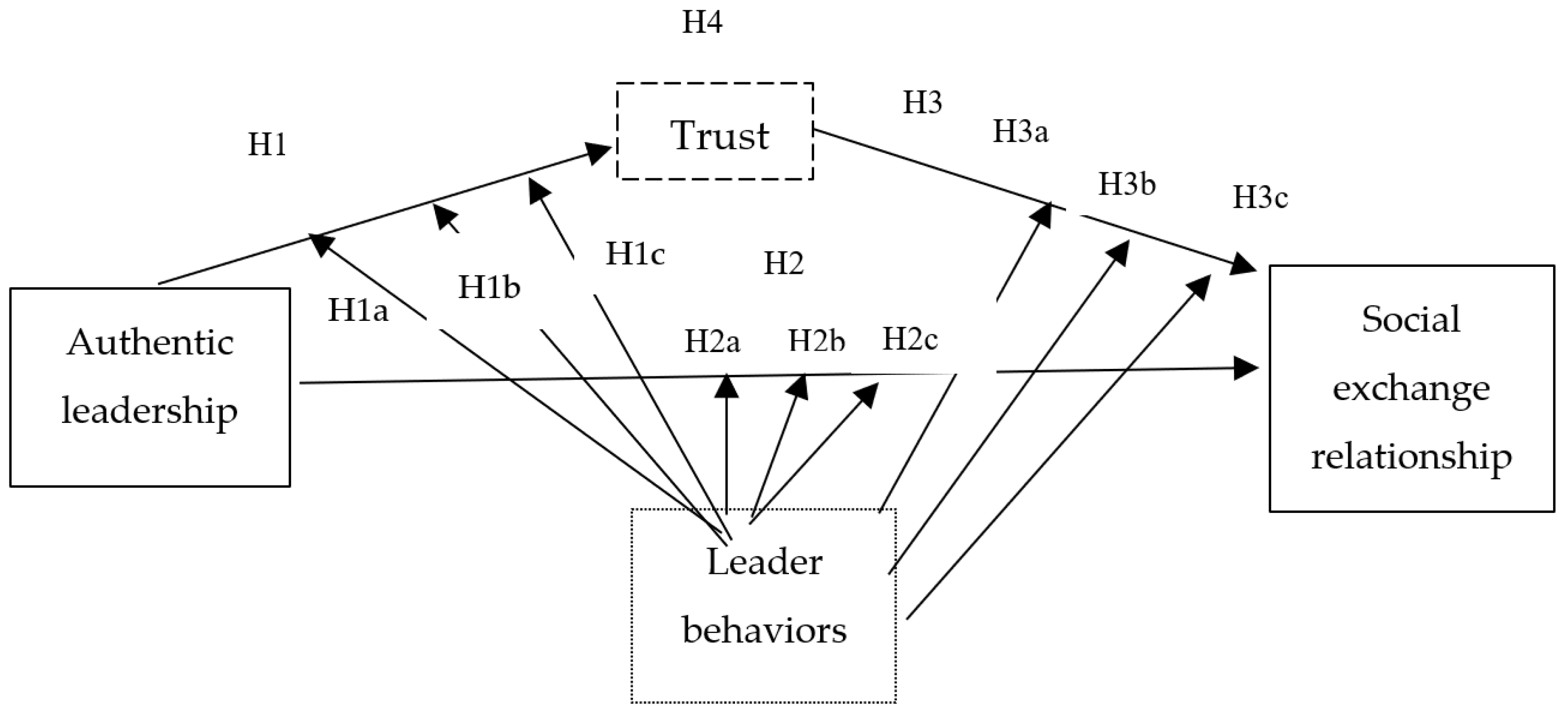

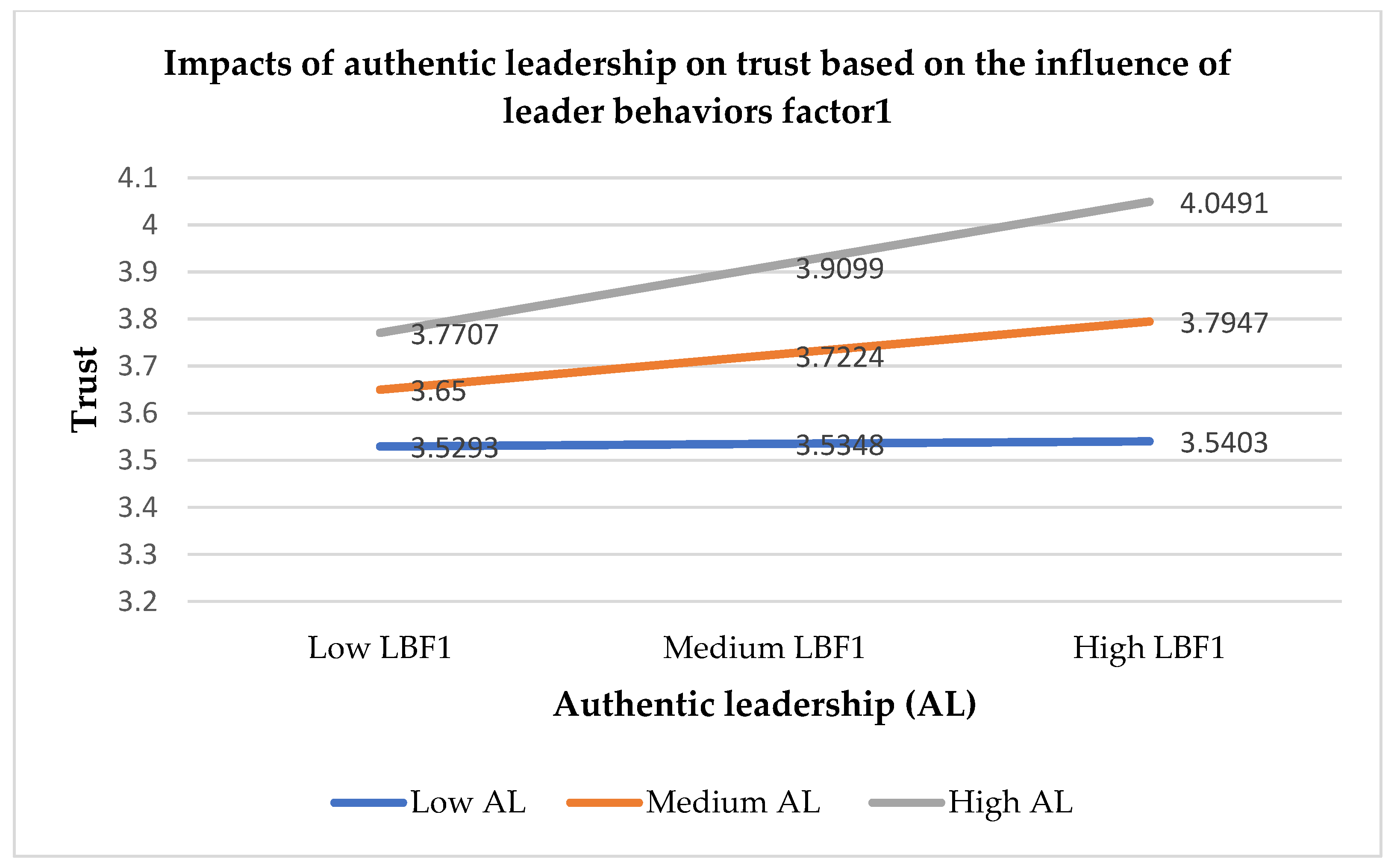

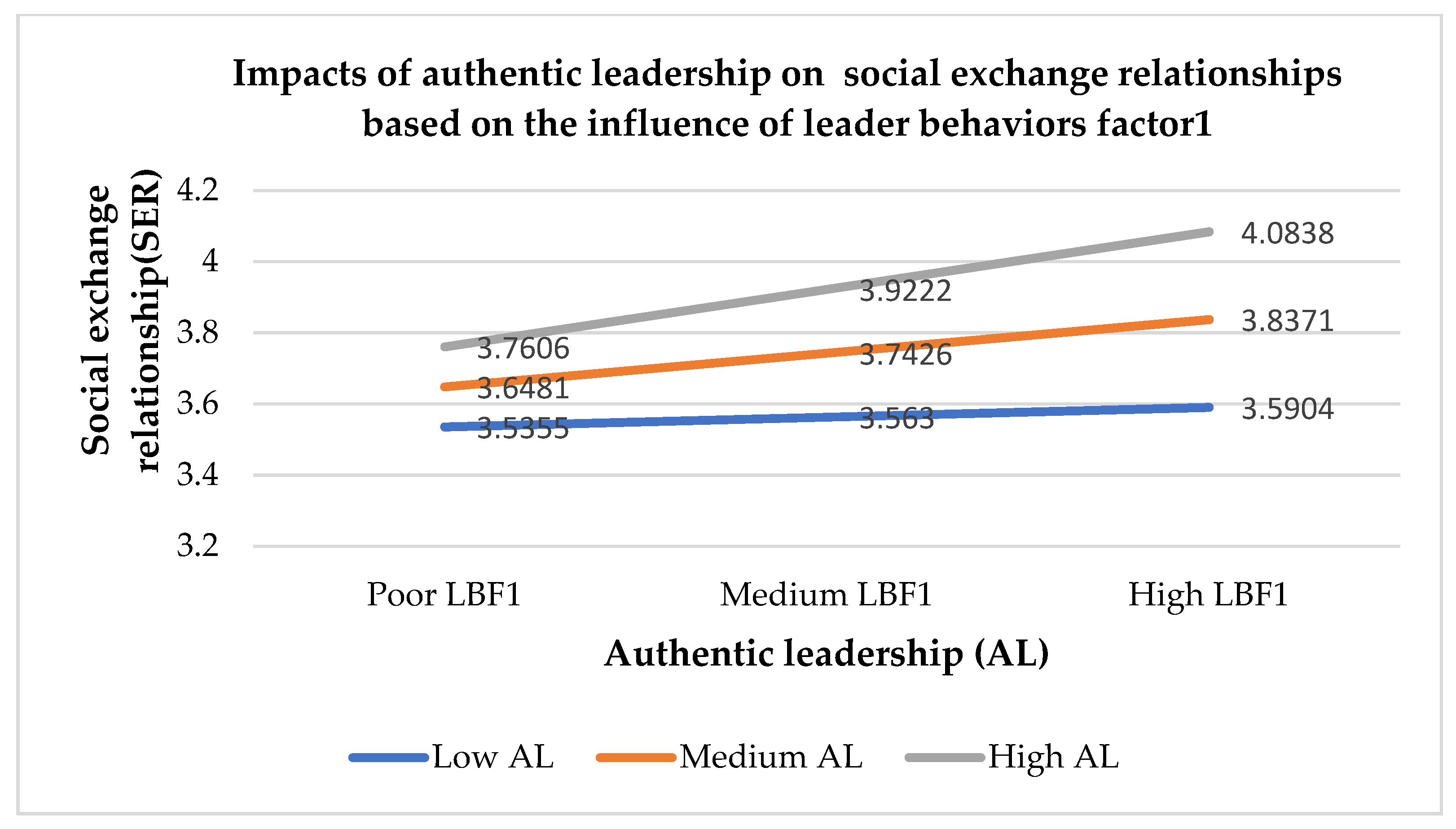

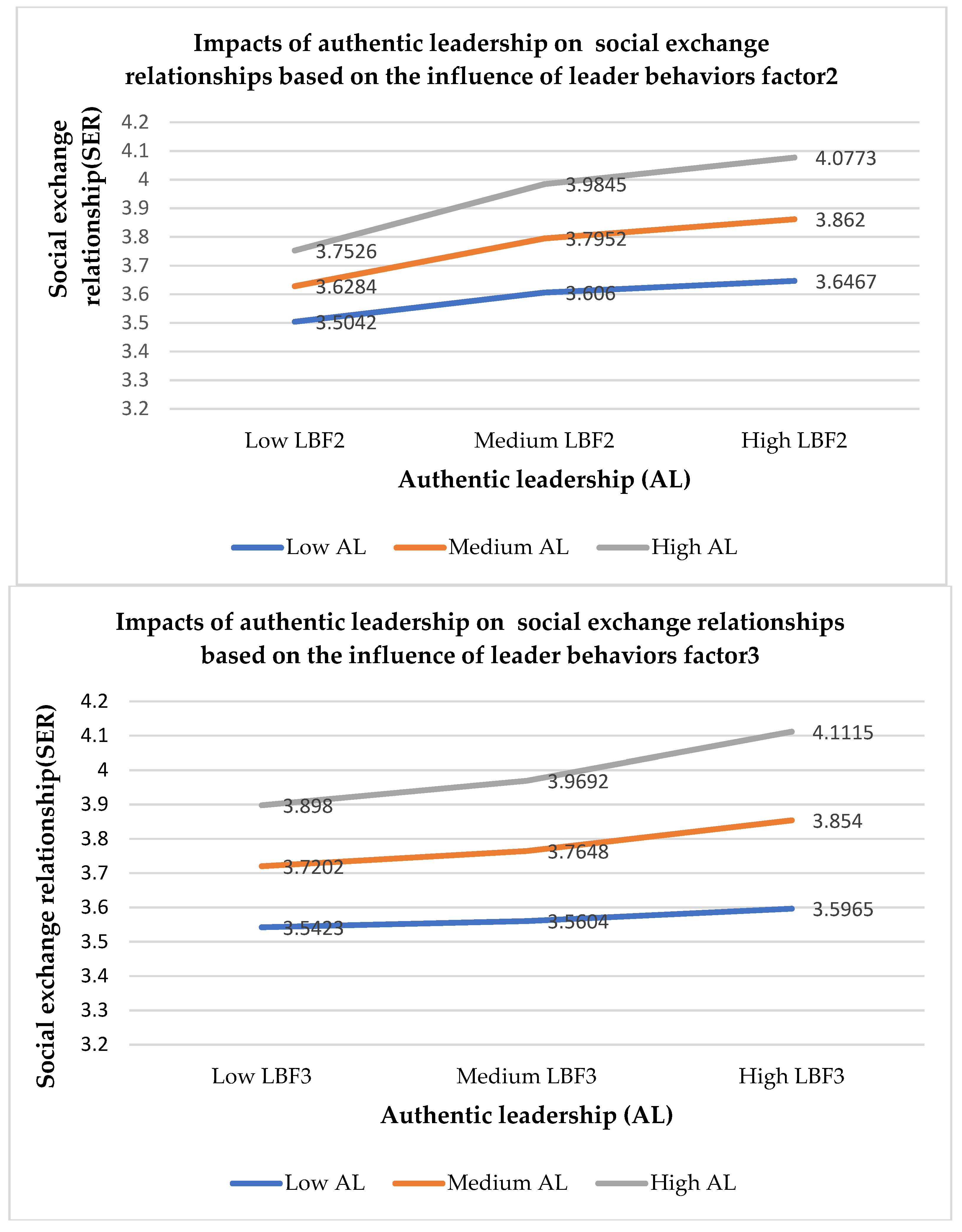

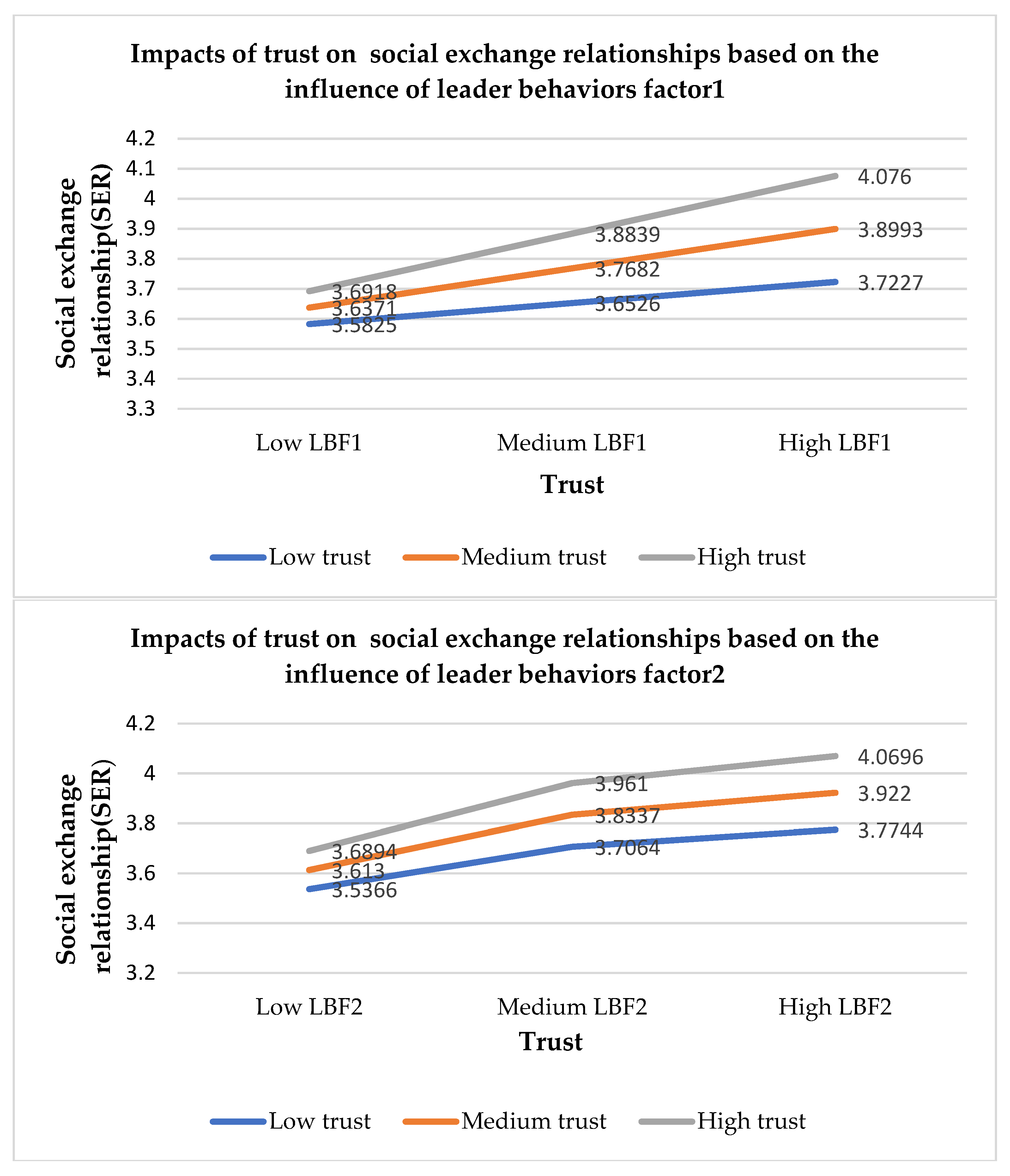

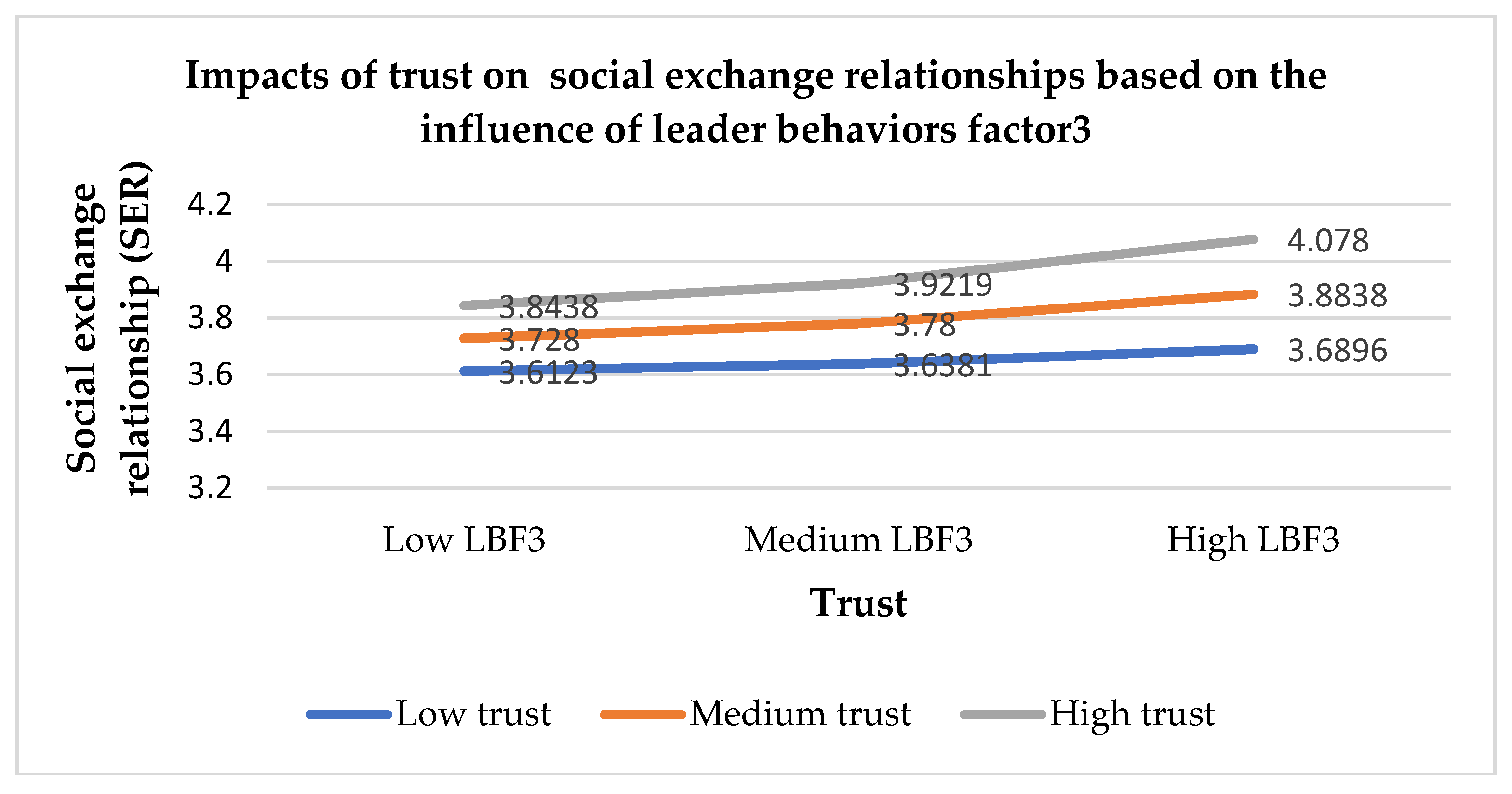

Leader behaviors with ability (LBF1) strengthen the positive relationship between authentic leadership and trust, between authentic leadership and social exchange relationships, and between trust and social exchange relationships during the pandemic. Based on LBF1 (see

Appendix B,

Table A2), this suggests that authentic leaders must give more support to followers and show their abilities in managing work and people during a crisis. Leaders need to show empathy with their followers and boost employee motivation and confidence. Finally, leaders’ action is required to promote trust and social exchange relationships. Cortez and Johnston [

103] argued that authentic leadership is associated with trust, social exchange relationships, commitment, reliability, values, and competency. Therefore, authentic leaders should focus on encouraging trust and social exchange relationships during COVID-19 [

49]. Elrod and Ramaley [

104] noted that decentralization is needed when rapid responses from leaders are required; therefore, shared leadership is critical during a crisis. Hence, a leader’s role can change based on their knowledge of and experience with solving problems based on the situation [

104]. Skillful leadership must include competencies in team building, coordination, problem-solving, and communication in order to improve trust and social exchange relationships [

23]. Therefore, the skills and styles of leaders strongly impact trust and social exchange relationships [

105]. Chou [

60] stated that employees’ perceived organizational support, such as being valued and cared for, can promote positive behaviors and attitudes toward the organization. Hence, employees’ perceived organizational support enhances high-quality social exchange relationships in the workplace. Dolan et al. [

54] argued that trust influences social exchange relationships. Additionally, high-quality social exchange relationships foster relationship satisfaction, which encourages better cooperation and performance in the organization [

48]. Thus, employees’ competence and self-determination are boosted when the organization supports them [

106]. Leaders need to have the ability to address employees’ needs, both physical and mental, to promote authentic leadership, trust, and social exchange relationships [

107].

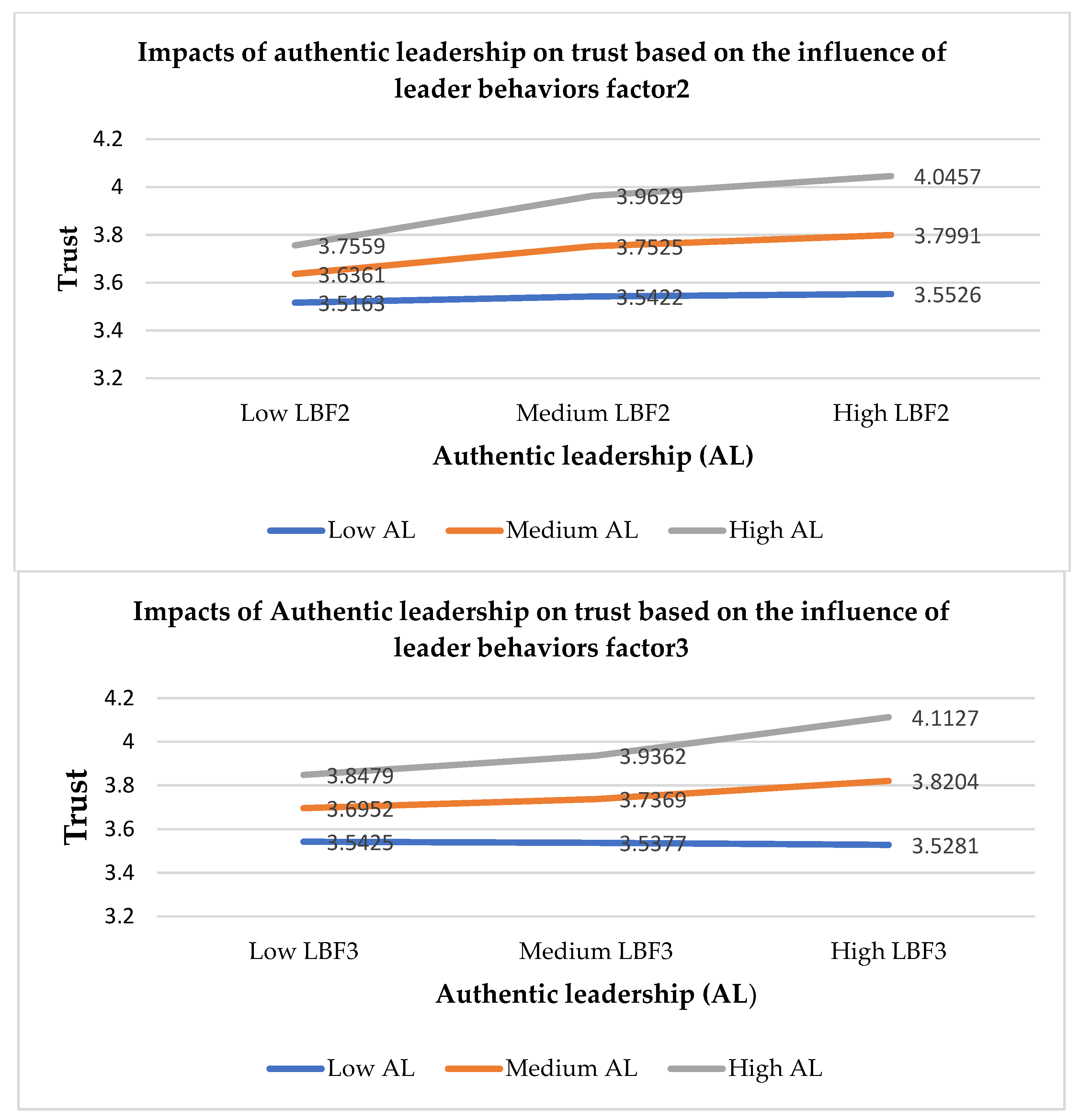

Leader behaviors with ethics (LBF2) enhance the positive relationship between authentic leadership and trust, authentic leadership and social exchange relationships, and trust and social exchange relationships during the pandemic. Based on LBF2 (see

Appendix B,

Table A2), this suggests that authentic leaders must focus on promoting ethics in the workplace. For example, leaders must take care of employees during the pandemic, and employees must be able to rely on their leaders [

107]. It is essential for leaders to have more upward and horizontal communication [

108] and meet employees’ expectations to improve trust and social exchange relationships. Hence, authentic leaders require high-quality leadership to maintain trust in the organization, which influences social exchange relationships [

65]. Creating a culture of trust is the first priority of skillful leaders to promote employee performance. Thereby, authentic leadership reinforces the employees’ emotional connection to the organization, enhancing their creativity and encouraging better job performance [

109]. The ethics underlying leaders’ behaviors positively affect employees’ behavior toward the organization. On the other hand, unethical leader behaviors, such as refusing to support their subordinates, giving them extra work, and having an unequal environment in the workplace, have negative consequences on employees’ psychological empowerment, bringing about unhappiness at work and lowered performance, which negatively impacts the organizational goals [

110]. Therefore, it is important for leader behaviors to consider ethics in their actions to promote authentic leadership and encourage strong social relationships.

Leader behaviors with positive relationships (LBF3) promote a positive relationship between authentic leadership and trust, between authentic leadership and social exchange relationships, and between trust and social exchange relationships during the pandemic. Due to the influence of COVID-19, people are forced to perform work from home. The effects of working from home change leader behaviors [

95]. Based on the results of the study, leader behaviors with a positive relationship suggest that remote work has an effect on the relationships between leaders and followers and among coworkers. Therefore, authentic leaders should focus on increasing trust and positive working relationships through online tools such as video calling services, instant communication tools, and task management platforms [

111]. Along with the importance of working in teams during the pandemic, trust is an essential element of collaboration and cooperation in the workplace; thus, social exchange or working relationships require trust, especially during telework [

12,

111]. Conversely, leaders with controlling and monitoring behaviors will diminish their leadership and interrupt trust and social exchange relationships in organizations [

12]. Hence, leaders who function with less control and more delegation and allow employees to participate in organizational matters can generate more trust to reduce the conflict between parties, promoting a social exchange relationship, leading to sustainable human capital management [

53,

95,

112]. A high-quality social exchange relationship will be generated based on the leader’s social skills and trustworthiness [

50]. Mental safety positively impacts social exchange relationships among employees, leading to good performance [

113,

114,

115].

Interpreting the Hypothesis Findings

Authentic leadership increases trust in leaders and organizations, facilitating a social exchange relationship, thus promoting better cooperation in the workplace. This kind of leadership shows authenticity or being genuine. If organizational leaders can show their true selves, employees know what they can expect from their leaders and how they can begin to establish trust in their workplace. Moreover, trust is generated from leaders’ consistent behavior and integrity and their transparency with those whom they lead [

59]. Additionally, authentic leadership significantly increases a leader–member social exchange relationship that enhances organizational goal accomplishment and organizations’ overall effectiveness and efficiency. Hence, authentic leaders must inspire and support the team to achieve organizational goals [

28]. A high level of trust also increases a high-quality social exchange relationship [

116]. Leader behaviors with ability, ethics, and positive relationships enhance authentic leadership, trust, and a social exchange relationship [

59]. During the pandemic, leader behaviors that have the ability to manage people and their work are strongly required to improve authentic leadership, trust, and a social exchange relationship [

23,

60,

104,

106,

107]. Leaders’ ability is necessary to build a trusting environment that promotes high social exchange relationships, since employees want leaders who can direct them to the right position and help them accomplish the common goal. Moreover, leader behaviors with ethics are strongly required to improve authentic leadership, trust, and social exchange relationships [

107,

108,

109,

110]. Ethical behaviors of leaders are essential during the first phase of COVID-19 because employees require mental and physical health safety, stability, and security in order to progress [

117]. On the basis of the social exchange theory, when employees perceive high social exchange relationships with ethical behaviors from leaders, they tend to develop feelings, such as trust, gratitude, and obligation, which motivate employees to provide benefit in return with positive attitudes and beneficial working behaviors such as taking charge [

118]. Finally, leader behaviors with positive relationships are strongly required to improve authentic leadership, trust, and social exchange relationships [

53,

95,

111,

112]. In establishing the relationships that inspire employees to achieve a common goal, leaders who can build positive organizational relationships through networking collaboration and conflict management are required [

119].

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This paper explores the associations among authentic leadership, trust, and social exchange relationships based on leader behaviors during the pandemic. The empirical study shows that authentic leadership is positively associated with trust and social exchange relationships. Qiu et al. [

80] noted that based on exchange theory, authentic leadership is associated with trust and integrity to handle the leader and follower relationship. Authentic leadership encourages trust, optimism, and cooperation among employees to support a high-quality social exchange relationship [

77,

81]. Furthermore, fair leadership is conducive to employees having trust in leaders and the organization [

120]. In addition, quality social exchange relationships influence positive leader and follower relationships [

86]. Strong leadership skills are essential for establishing high-quality social exchange relationships to keep employees from leaving the organization [

121].

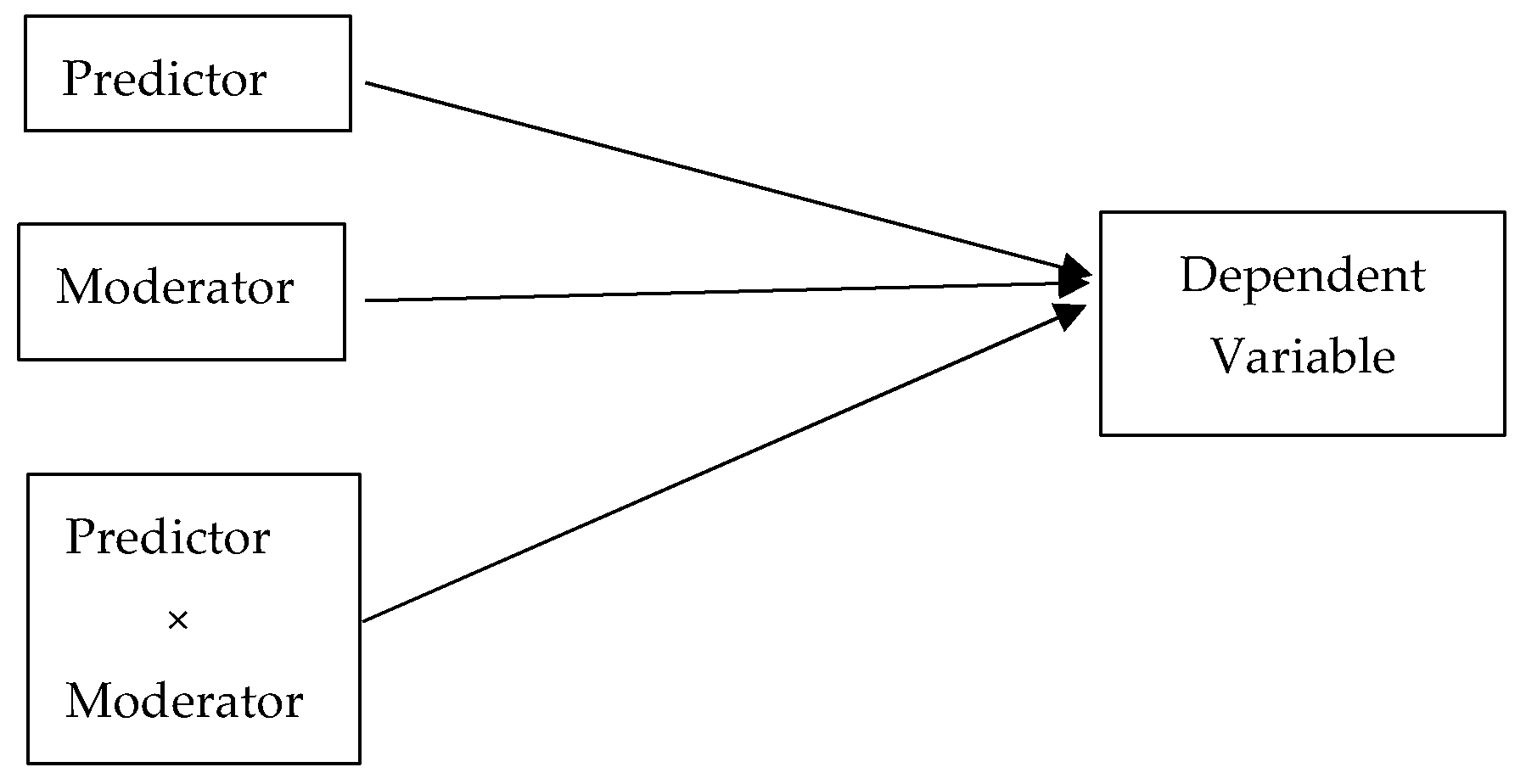

Applying leader behavior factors (LBF1, LBF2 and LBF3) as moderators positively influences the associations among authentic leadership, trust, and social exchange relationships during the pandemic. The leader behavior factors include 13 sub-factors, which are shown in

Appendix B,

Table A2.

Regarding LBF1, a leader’s ability to manage work and people is necessary to improve authentic leadership, trust, and high-social exchange relationships. Leaders should focus on boosting employee motivation and confidence to encourage their performance. Leaders must have empathy and know how to support their employees. Therefore, they required the ability to address their employees’ needs [

107]. It is necessary for leaders to take action and respond rapidly to situations in order to increase trust in leaders and organizations during this crisis; thus, shared leadership is required to solve problems more quickly according to the situation [

74]. Shared leadership positively impacts agility, innovation, and collaboration among employees [

104]. During the pandemic, authentic leadership should provide long-term and short-term planning that integrates standard solutions with solutions outside the box [

74].

In regard to LBF2, leader behaviors with ethics and social skills positively impact authentic leadership, trust and social exchange relationships. During the first phase of the pandemic, the basic needs of employees were safety, stability and security, including their physical and mental well-being; over time, those needs have evolved, requiring more complicated procedures [

50]. Emmett et al. [

50] indicated that to show strong leadership, leaders must understand the most crucial needs of employees so they can make changes to the organizational operation while being action-oriented, empathetic and transparent. Conversely, unethical leader behaviors negatively affect employees’ psychological outcomes, reducing their performance efficiency and happiness at work, leading to decreased leadership, trust, and social exchange relationships; thus, leaders behaving ethically is crucial to develop employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors, leading to sustainable organizational management [

110]. Additionally, leaders can improve trusting relationships, social cohesion, and personal purpose by prioritizing actions that can cover a broad range of needs for the majority of employees. Finally, by applying the combination of technology, data, and analytics to identify employees who are confronting unexpected changes, leaders can support their employees in meaningful ways. Thus, leaders should keep listening to their employees, share information transparently and empathetically, and develop a plan to implement changes with clear communication to build employees’ trust, confidence and the working relationship during this crisis [

50].

Regarding LBF3, leader behaviors with positive relationships are essential for improving authentic leadership, trust and high social exchange relationships. During the pandemic, many employees have had to work from home due to government policies, including social distancing, to alleviate COVID-19 infection. Working from home has changed the way people work. There are both advantages and disadvantages of working from home. Many reports argue that working from home negatively impacts trust between leaders and followers, and diminished social exchange relationships in the organization become one of the disadvantages [

111]. Contreras et al. [

122] noted that effective leaders view working from home as an advantage for organizational productivity, the environment, and workers. However, leaders must shift the hierarchical work structure to make it less complex to increase the effectiveness of working from home. In addition, leaders must have the ability to build trust with team members and establish a virtual presence to help with and promote association and communication among them. Therefore, it is necessary to select suitable communication tools. In the telework environment, effective communication is required; hence, it should be developed by providing training programs for organizational members. Successful work from home requires leaders who pursue positive relationships in the organization to build strong trust and high-level social exchange relationships [

123]. Additionally, to promote a positive relationship environment, authentic leaders need interpersonal skills, such as active listening and communication and the ability to inspire in order to encourage social exchange relationships in the workplace [

88,

124].

Moreover, organizations should promote humble behavior by providing a training program for leaders and employees to support a friendly working environment [

9].

5.3. Practical Implications

The implications of this study can be of benefit to managers and practitioners under pandemic pressure when reviewing the literature from different countries. Authentic leadership behaviors and trust are imperative in order to increase social exchange relationships. Employees need leaders’ guidance to pointing them in the right direction. Therefore, the trustworthiness of leaders is a vital factor that can enhance trust and social exchange relationships in organizations. The following practical implications are suggested:

Authentic leaders must have the ability to manage their stress in order to deliver decisions and take actions effectively. When leaders express stress in highly emotional ways, employees’ stress and anxiety can increase. Authentic leaders must share information with empathy and optimism to reduce employees’ stress. Leaders should understand and address employees’ stress and anxiety, e.g., by reducing work hours, and clarify that there is hope for them and that help is available in these situations.

Authentic leaders must have credibility to establish trust in them and their organizations by showing honesty and transparency. Trustworthiness of leaders is vital to enhance trust in organizations and social exchange relationships. The three dimensions of trustworthiness are ability, benevolence, and integrity, which can promote a culture of trust, leading to high-quality social exchange relationships. They can improve trust and positive working relationships by delivering bad news or facts quickly and straightforwardly and providing a communication routine for employees, and they can follow current situations. Employee feedback is important, because sometimes employees want to give leaders suggestions. Finally, leaders should be role models for employees in a crisis, such as by cutting back on travel and practicing social distancing.

Authentic leaders must have strong social skills to maximize trust and minimize stress, which contributes to increased social exchange relationships. Social skills comprise communication, influence, cooperation and collaboration, leadership, conflict management, catalyzing change and building bonds. These skills can develop employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors, which influence them to support one another.