Segmentation by Motivations in Sustainable Coastal and Marine Destinations: A Study in Jacó, Costa Rica

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourist Demand Motivations in Coastal and Marine Destinations

2.2. Demand Segmentation in Coastal and Marine Destinations

2.3. Satisfaction and Loyalty in Coastal and Marine Tourism

3. Methodology

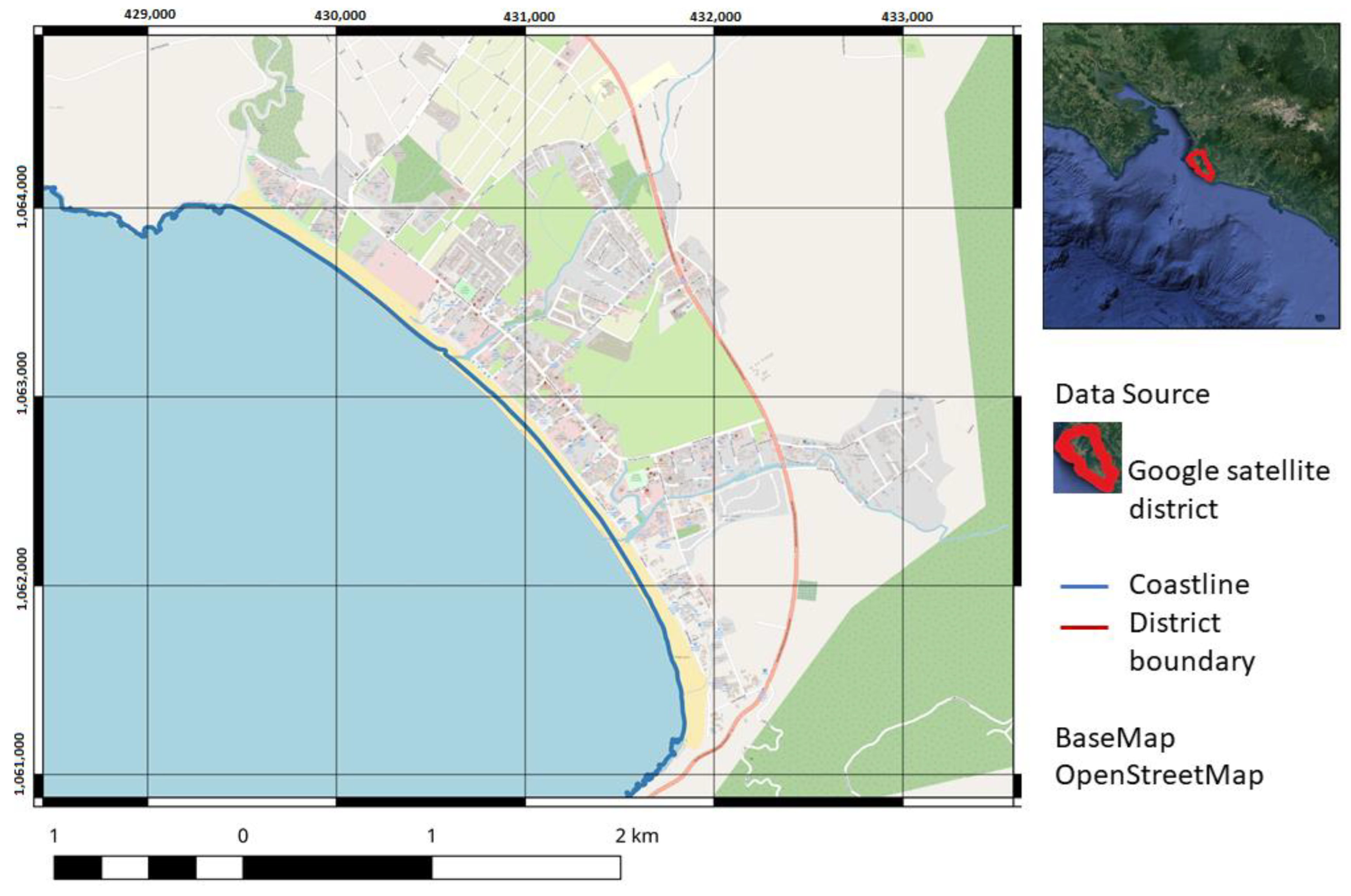

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Survey, Data Collection, and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Aspects of the Samples

4.2. Motivation of the Demand—Factor Analysis

4.3. Segmentation

4.4. Segmentation by Sociodemographic Variables

4.5. Relationship between Tourist Segments and Satisfaction and Return Intentions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlsson-Szlezak, P.; Reeves, M.; Swartz, P. What Coronavirus Could Mean for the Global Economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 3, 1–10. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-coronavirus-could-mean-for-the-global-economy (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Fuchs, C. Everyday life and everyday communication in coronavirus capitalism. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. J. Glob. Sust. Inf. Soc. 2020, 18, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.; Parkb, J.; Na Lic, S.; Songb, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization UNWTO. The Worst Year in the History of Tourism, with Billion Less International Arrivals. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/en/news/2020-the-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-a-billion-fewer-international-arrivals (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Galvani, A.; Lew, A.A.; Perez, M.S. COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, Ľ.; Kolačkovská, J.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C.; Lukáč, M. Perception of the Impacts of Tourism by the Administrations of Protected Areas and Sustainable Tourism (Un) Development in Slovakia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geog. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibn-Mohammed, T.; Mustapha, K.B.; Godsell, J.; Adamu, Z.; Babatunde, K.A.; Akintade, D.D.; Acquaye, A.; Fujii, H.; Ndiaye, M.M.; Yamoah, F.A.; et al. A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Res. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M. Coastal and marine tourism: A challenging factor in Marine Spatial Planning. Ocean Coast Manag. 2016, 129, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orams, M.; Lueck, M. Coastal Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- Orams, M.; Lueck, M. Marine tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 585–586. [Google Scholar]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Motivation and segmentation of the demand for coastal and marine destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolal, M.; Rus, R.V.; Cosma, S.; Gursoy, D. A pilot study on spectators’ motivations and their socio-economic perceptions of a film festival. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2015, 16, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.K.; Horridge, P.E. Travel motivations as souvenir purchase indicators. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Sarangi, P. Modeling attributes of religious tourism: A study of Kumbh Mela, India. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2019, 20, 296–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, V.R. Motivations to cruise: An itinerary and cruise experience study. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.T.; Ip, W.H.; Lee, C.K.M.; Mou, W.L. Customer grouping for better resources allocation using GA based clustering technique. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 1979–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Ahmed, S. Factors influencing destination image and visit intention among young women travellers: Role of travel motivation, perceived risks, and travel constraints. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, L.A.; Lehto, X.Y.; Huang, J. A missing link in understanding revisit intention: The role of motivation and image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Jung, S. Festival attributes and perceptions: A meta-analysis of relationships with satisfaction and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.L.; Backman, K.F.; Huang, Y.C. Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 8, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Tepanon, Y.; Uysal, M. Measuring tourist satisfaction by attribute and motivation: The case of a nature -based resort. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; Caballero, R.; González, M.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; Pérez, F. Goal programming synthetic indicators: An application for sustainable tourism in Andalusian coastal counties. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2158–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Martínez, M.L.; Nahuacatl, R.C. Is the protection of beach and dune vegetation compatible with tourism? Tour Manag. 2017, 58, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drápela, E.; Boháč, A.; Böhm, H.; Zágoršek, K. Motivation and Preferences of Visitors in the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark. Geosciences 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, M.; Slabbert, E. The relevance of the tangible and intangible social impacts of tourism on selected South African communities. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2016, 14, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C. Marine tourist motivations comparing push and pull factors. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 15, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre, R.P.; Phakdee-Auksorn, P. Examining Tourists’ Push and Pull Travel Motivations and Behavioral Intentions: The Case of British Outbound Tourists to Phuket, Thailand. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 18, 437–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, Ö.; Sahin, I.; Ryan, C. Push-motivation-based emotional arousal: A research study in a coastal destination. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, P.; Slabbert, E.; Saayman, M. Travel motivations of tourists to selected marine destinations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rid, W.; Ezeuduji, I.O.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. Segmentation by motivation for rural tourism activities in The Gambia. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L. Motivation-based segmentation of yachting tourists in China. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Corre, N.; Saint-Pierre, A.; Hughes, M.; Peuziat, I.; Cosquer, A.; Michot, T.; Bernard, N. Outdoor recreation in French Coastal and Marine Protected Areas. Exploring recreation experience preference as a way for building conservation support. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 33, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, N.P.; Jorgenson, J.; Boley, B.B. Are sustainable tourists a higher spending market? Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudež, H.N.; Sedmak, G.; Bojnec, Š. Benefit segmentation of seaside destination in the phase of market repositioning: The case of Portorož. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.K.; Chang, K.C.; Sung, Y.F. Market segmentation of international tourists based on motivation to travel: A case study of Taiwan. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M.; Cater, C. Mass tourism underwater: A segmentation approach to motivations of scuba diving holiday tourists. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Tseng, C.H.; Lin, Y.F. Segmentation by recreation experience in island-based tourism: A case study of Taiwan’s Liuqiu Island. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafi, M.; Flannery, W.; Murtagh, B. Coastal tourism, market segmentation and contested landscapes. Mar. Policy 2020, 121, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofri, L.; Nunes, P.A. Beach ‘lovers’ and ‘greens’: A worldwide empirical analysis of coastal tourism. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 88, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Segmentation of foreign tourist demand in a coastal marine destination: The case of Montañita, Ecuador. Ocean Coast Manag. 2019, 167, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. From motivation to segmentation in coastal and marine destinations: A study from the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2325–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, M.H.; Parreira, A.; Moutinho, L. Motivations, emotions and satisfaction: The keys to a tourism destination choice. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyen, K.N.; Nghi, N.Q. Impacts of the tourists’ motivation to search for novelty to the satisfaction and loyalty to a destination of Kien Giang marine and coastal adventure tourism. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Res. 2019, 4, 2807–2818. Available online: http://www.ijsser.org/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Sangpikul, A. The effects of travel experience dimensions on tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The case of an island destination. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G.; Cladera, M.; Pencarelli, T. Does sustainability matter to package tourists? The case of large-scale coastal tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Olya, H.G.; Maleki, P.; Dalir, S. Behavioral responses of 3S tourism visitors: Evidence from a Mediterranean Island destination. Tour. Manag. Perspec. 2020, 33, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Paradise for who? Segmenting visitors’ satisfaction with cognitive image and predicting behavioral loyalty. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Rican Tourism Institute|ICT. Metadata of the Studies Carried Out by the ICT. 2021. Available online: https://www.ict.go.cr/es/documentos-institucionales/estad%C3%ADsticas/cifras-tur%C3%ADsticas/visitaa-las-%C3%A1reasssilvestre-protegidas-sinac/1397-2017-2/file.html (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Government of Costa Rica. Costa Rica is Awarded as the Best Responsible Tourism Destination at the WTM Latin Awards America. Presidency of the Republic of Costa Rica. 2021. Available online: https://www.presidencia.go.cr/comunicados/2021/05/costa-rica-es-premiada-como-mejor-destino-de-turismo-responsable-en-los-premios-wtm-latin-america (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Kim, K.-H.; Park, D.-B. Relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: Community-based ecotourism in Korea. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Component | Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Interest in myths and legends | 0.850 | Learning and coastal experience | ||||

| Interest in experiencing historical attractions | 0.748 | |||||

| Interest in local languages | 0.741 | |||||

| Interest in experiencing culture and traditions | 0.718 | |||||

| Interest in learning traditional dances | 0.711 | |||||

| Interest in staying among the coastal population | 0.683 | |||||

| Interest in typical coastal gastronomy | 0.665 | |||||

| Interest in the history and culture of Jacó | 0.634 | |||||

| Interest in sharing experiences with the local population | 0.622 | |||||

| Interest in the lifestyle of the coastal population | 0.600 | |||||

| Interest in local crafts | 0.567 | |||||

| Wanting to visit family and friends | 0.556 | |||||

| Recognizing the importance of tourism in natural spaces | 0.810 | Nature | ||||

| Recognizing the importance of marine coastal tourism | 0.772 | |||||

| Experiencing marine wildlife sites and national parks | 0.701 | |||||

| Interest in experiences related to the coastal landscape | 0.660 | |||||

| Knowing the flora and fauna | 0.529 | |||||

| Interest in their tourist attractions | 0.528 | |||||

| Interest in rest and relaxation | 0.795 | Rest and safety | ||||

| Interest in safety and protection | 0.757 | |||||

| Interest in the environmental quality of air, water, and soil | 0.708 | |||||

| Interest in the importance of water sports | 0.774 | Water sports | ||||

| Wanting to see things I don’t normally see | 0.705 | |||||

| Interest in the importance of swimming | 0.648 | |||||

| Interest in the nightlife | 0.847 | Nightlife | ||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.923 | 0.877 | 0.800 | 0.762 | - | |

| Eigenvalue | 10,460 | 2734 | 1474 | 1198 | 1004 | |

| Variance explained (%) | 41,838 | 10,937 | 5897 | 4793 | 4015 | |

| Cumulative variance explained (%) | 41,838 | 52,775 | 58,672 | 63,465 | 67,479 | |

| Variable | Multiple Motives | Passive Tourists | Eco-Coastal | Kruskal–Wallis H | Mann–Whitney U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning and coastal experience | 3.8 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 157,190 | All |

| Nature | 4.4 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 47,798 | All except 1 |

| Rest and safety | 4.6 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 32,313 | All |

| Water sports | 4.3 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 21,135 | There except 2–3 |

| Nightlife | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | None | None |

| Variable | Multiple Reasons (%) | Passive Tourist (%) | Eco-Coastal (%) | Overall (%) | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | National | 17.7 | 27.5 | 9.1 | 15.2 | 9128; p < 0.05 |

| Foreign | 82.3 | 72.5 | 90.9 | 84.8 | ||

| Origin | North America | 73.1 | 60.0 | 87.9 | 77.8 | 19,538; p < 0.05 |

| Europe | 1.5 | 1.7 | ||||

| South America | 7.7 | 12.5 | 3.0 | 6.3 | ||

| rest of the world | 16.9 | 27.5 | 7.6 | 14.2 | ||

| Professional activity | Student | 10.0 | 42.5 | 30.3 | 23.2 | 37,073; p < 0.05 |

| Researcher/scientist | 0.8 | 0.3 | ||||

| Entrepreneur/business Owner | 10.0 | 10.0 | 11.4 | 10.6 | ||

| Employee private | 56.2 | 35.0 | 34.1 | 43.7 | ||

| Employee public | 11.5 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 8.6 | ||

| Retired | 1.5 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 3.0 | ||

| Unemployed | 3.8 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 5.6 | ||

| Others | 6.2 | 5.3 | 5.0 | |||

| Monthly income | Less than USD 500 | 10.8 | 32.5 | 30.3 | 22.2 | 21,104; p < 0.05 |

| From USD 500 to USD 999 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 12.6 | ||

| From USD 1000 to USD 1499 | 16.9 | 12.5 | 14.4 | 15.2 | ||

| From USD 1500 to USD 1999 | 20.0 | 15.0 | 10.6 | 15.2 | ||

| From USD 2000 to USD 2499 | 11.5 | 10.0 | 8.3 | 9.9 | ||

| From USD 2500 to 2999 | 13.8 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 11.3 | ||

| More than USD 3000 | 14.6 | 7.5 | 14.4 | 13.6 | ||

| Average daily expense | less than USD 100 | 11.5 | 30.0 | 16.7 | 16.2 | 55,360; p < 0.05 |

| USD 100–USD 149 | 31.5 | 20.0 | 35.6 | 31.8 | ||

| USD 150–USD 199 | 33.1 | 10.0 | 21.2 | 24.8 | ||

| USD 200–USD 249 | 13.8 | 14.4 | 12.3 | |||

| USD 250–USD 299 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 4.3 | ||

| More than USD 300 | 4.6 | 37.5 | 8.3 | 10.6 | ||

| Variable | Multiple Motives | Passive Tourists | Eco-Coastal | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall satisfaction | 4.37 | 3.48 | 4.87 | 91,039; p < 0.05 |

| Return intentions | 4.08 | 3.03 | 3.77 | 62,495; p < 0.05 |

| Intentions to recommend this destination | 4.25 | 3.63 | 3.80 | 40,216; p < 0.05 |

| Intentions to spread positive word of mouth about Jacó | 4.45 | 3.93 | 3.99 | 43.242; p < 0.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvache-Franco, M.; Víquez-Paniagua, A.G.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Pérez-Orozco, A.; Carvache-Franco, O. Segmentation by Motivations in Sustainable Coastal and Marine Destinations: A Study in Jacó, Costa Rica. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148830

Carvache-Franco M, Víquez-Paniagua AG, Carvache-Franco W, Pérez-Orozco A, Carvache-Franco O. Segmentation by Motivations in Sustainable Coastal and Marine Destinations: A Study in Jacó, Costa Rica. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148830

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvache-Franco, Mauricio, Ana Gabriela Víquez-Paniagua, Wilmer Carvache-Franco, Allan Pérez-Orozco, and Orly Carvache-Franco. 2022. "Segmentation by Motivations in Sustainable Coastal and Marine Destinations: A Study in Jacó, Costa Rica" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148830

APA StyleCarvache-Franco, M., Víquez-Paniagua, A. G., Carvache-Franco, W., Pérez-Orozco, A., & Carvache-Franco, O. (2022). Segmentation by Motivations in Sustainable Coastal and Marine Destinations: A Study in Jacó, Costa Rica. Sustainability, 14(14), 8830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148830