Heritage Tourism and Nation-Building: Politics of the Production of Chinese National Identity at the Mausoleum of Yellow Emperor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Heritage Tourism and National Identity

2.2. Landscape and Nation-Building

2.3. Toponymy and Politics of Place Naming

2.4. Nation-Building through Landscape Naming and Ritual Experience

3. Methods

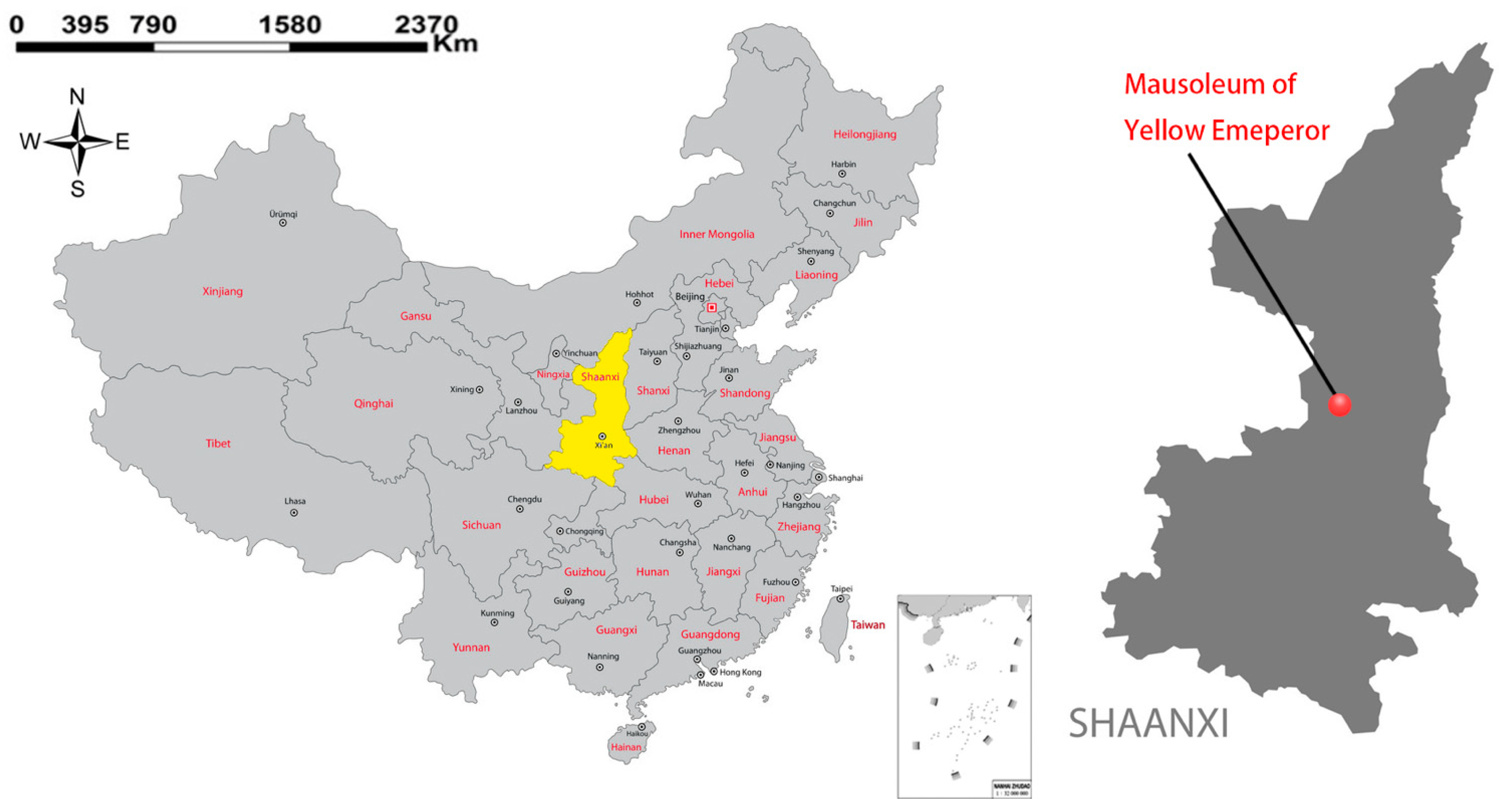

3.1. Research Site: The Mausoleum of the Yellow Emperor

3.2. The Mausoleum of Yellow Emperor and Memorial Ceremony: Origin, History, and Changes

3.2.1. Traditional Yellow Emperor Memorial Ceremony: Before 1949

3.2.2. A local Ritual Ceremony: Between 1949 and 1978

3.2.3. The National-Level Ritual Ceremony: After 1978

3.3. Research Methods

4. Landscape Naming and Practices of Nation-Building in the Mausoleum of the Yellow Emperor

4.1. Landscape Naming and Reinforcement of National Identity

The temple courtyard has 95 steps, representing the Yellow Emperor’s lofty status. Here we will see a variety of landscape images with the symbol of dragon. We are the descendants of the dragon. Like what we can see from this stone tablets sign by Deng Xiaoping, the founding father of the country. The four big characters ‘descendants of the Yellow Emperor’ are clearly displayed on the stone tablet in the pavilion of stone tablets.

4.2. Ritual Practices and National Identity

Every year, when we offer sacrifices to our ancestor especially on the occasion of the memorial ceremony, we often prepare 34, because there are 34 provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities and special administrative regions under the central government. Fifty-six naturally means 56 ethnic groups, because the present memorial ceremony is arranged by the province, and the political representatives of central government will also participate.

There are nine dragon flags and nine phoenix flags respectively, implying the splendid nine dragon dynasty, nine phoenix flying, and the auspicious dragon and phoenix, symbolizing the solemn and powerful ceremony. 56 dragon flags mean that the Chinese people are the descendants of the dragon, and 56 nationalities jointly worship the Yellow Emperor as the ancestor of the Chinese nation.

There is a strict limit on the number of offerings like 56 steamed buns for sacrifice on the ceremony, a symbol of the unity of 56 ethnic groups. This number is required by the county and the province. It can’t be changed casually. One year, I changed the pattern and number, made 12 kinds of steamed buns with the appearance of Chinese zodiac, which were returned by the government and asked to be redone. Neither the appearance nor the quantity can be changed.

5. Perception of the Nation and National Identity through Ritual Performance

5.1. Ordinary Visitors’ Experience and Perception

Qingming is a national festival to memorize the ancestors. The Yellow Emperor is the common ancestor for all Chinese, as descendants of China and the Yellow Emperor, no matter where we are, all workers, peasants, intellectuals, people in Taiwan, overseas Chinese and all people should contribute to the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and the reunification of the motherland.

When I was a child, my parents would bring me to worship our ancestor on Tomb Sweeping Day. At that time, the happiest thing was to get some sacrificial offerings after the worshipping ceremony, which was regarded as the luckiest thing. As the native resident, growing up here in Huangling, this is the place like our home where all our emotion and affection belongs to. When we attend the ceremony, we can see people from all walks of life, and we all share the same past. We are all parts of the descendants of [the] Yellow Emperor because we share one common ancestor.

I have lived in the UK for 17 years and my hometown is in Shaanxi Province. This time I bring my families to attend the ceremony. The ceremony was magnificent and grand. When we are at the site of the mausoleum, when we hear the ancient music, listen to the past history and suffering of the Chinese nation with other compatriots, the memorial ceremony reminds us our past life in China. We feel that we are not alone, wherever we go, we always belong to the Chinese nation. We have the same ancestor and we have our roots here. We are connected with our motherland by blood tie, no one can cut it off (Interview with overseas Chinese tourists).

The memorial ceremony was quiet spectacular. Many people came including political representatives from the national government. I heard that China’s top leaders had also come before. As senior citizens, our lives are quite good now compared with the past. I remember in the past, there were not so many magnificent pavilions and grand buildings here. Thanks to our old ancestor, thanks to the communist party of China and our country, praying for our ancestor to protect our happy life. We are all descendants of the Yellow Emperor; I am proud to be part of the Chinese nation. I hope the ancestor will bless and protect us. We wish our country becomes stronger and more prosperous.

5.2. Taiwanese Visitors’ Experience and Perception

Our first history class is about the story of the Yellow Emperor. We know that we are the descendants of the Yellow Emperor, but we only hear stories from books. The memorial ceremony left us with a deep impression. We were quite excited to attend the ceremony. When wearing the Yellow sacrificial kerchief, which symbolizes the descendants of the Chinese people, there is a sense of coming back to the hometown. When I came here I knew where my nation came from and how the blood was spread. We have the common origin and ancestor. There are only some differences in our accents; as long as we communicate, there are no cultural barriers and difficulties. After going back, I will share my experience with my friends. I hope they will have the chance to come here to find their roots and worship their ancestors.

I was told in 1984, when the first Taiwanese came back to participate in the worshiping activity, their clothes displayed phrases such as ‘xiang nian zuguo’ (‘missing motherland’), ‘zuzong de erzi’ (‘son of motherland’), and ‘zhongyuhuijiale’ (‘finally coming home’). They were very devoted and excited. I was impressed. When I attended the memorial ceremony myself, I strongly felt we are part of the national culture and we are the descendants of the Yellow Emperor.

My father left the mainland for Taiwan on 15 March 1949. This is my first time to participate in this worshiping ceremony. I think I should come because it is our Chinese’s ancestor. I have read about the culture of the Yellow Emperor in the history textbooks before. This time, while watching the performance of drum and bell ringing, I was moved by the respectful reading of sacrificial articles, music and dancing performance in the ceremony. I think I will come again.

During Tomb Sweeping Day, the descendants of Yellow Emperor gathered at Qiaoshan at home and abroad, worshiped the Yellow Emperor, and planted the cypress in Qiaoshan, which will help to enhance the unity of compatriots across the Straits, and further deepening friendship and cohesion. The cypress planted today will surely thrive and become a towering tree. Instead of worshiping our ancestor, it will silently express our sincere feelings and deep homesickness. Tree-planting activities for ancestors have enhanced the cohesion of the Chinese nation. We cherish the friendship between our compatriots from all over the world and their blood ties. We should continue to publicize, inherit and carry forward the Chinese civilization created by the Chinese people’s ancestor.

6. Conclusions and Discussions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abili, M.; Zhao, Y. Planning and managing restrictions and barriers to tourism development between Iran and China. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, Y. Making a homeland, constructing a diaspora: The case of Taglit-Birthright Israel. Political Geogr. 2017, 58, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K. Tourism and the geopolitics of Buddhist heritage in Nepal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 75, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. Tourism as political theatre in North Korea. Political Geogr. 2019, 68, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowler, L. Waging Hospitality: Feminist Geopolitics and Tourism in West Belfast Northern Ireland. Geopolitics 2013, 18, 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, J.; Mostafanezhad, M. Geopolitical encounters of tourism: A conceptual approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, E.L.E. ‘Refugee’ or ‘returnee’? The ethnic geopolitics of diasporic resettlement in China and intergenerational change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.C.; Del Casino, V.J. Negative simulation, spectacle and the embodied geopolitics of tourism. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2018, 43, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafanezhad, M.; Promburom, T. “Lost in Thailand”: The popular geopolitics of film-induced tourism in northern Thailand. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2018, 19, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Tourism and geopolitics: Issues and concepts from central and Eastern Europe. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C. Tourism and geopolitics: Issues and concepts from Central and Eastern Europe. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 142–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J. Paying homage to the ‘Heavenly Mother’: Cultural-geopolitics of the Mazu pilgrimage and its implications on rapprochement between China and Taiwan. Geoforum 2017, 84, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, H.Y. Heritage Tourism: Emotional Journeys into Nationhood. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 37, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, R.; Morais, D.B.; Chick, G. Religion and identity in India’s heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 790–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pretes, M. Tourism and nationalism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsale, A. Jewish heritage tourism in Bucharest: Reality and visions. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortenberry, B.R. Heritage justice, conservation and tourism in greater Caribbean. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfehani, M.H.; Albrecht, J.N. Planning for intangible Cultural Heritage in Tourism: Challenges and Implications. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 980–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y. Intangible heritage: Reimaging two Koreas as one nation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 520–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.; Timms, K.; Schaffer, V.; Skavronskaya, L.; Little, C. Management of immersive heritage tourism experiences: A conceptual model. Tour. Manag. 2018, 72, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, S.; Min, C.-K.; Roh, T.-S. Impacts of UNESCO-listed tangible and intangible heritages on tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhu, H. The translocal practices of intangible cultural heritage in the perspective of geography. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 492–504. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E.; Waston, S. The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Zhang, J. The impact of place on the monopoly profit of a geographical indication product: A case of Dongting Biluochun tea in Suzhou. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2015, 35, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.C.; Li, L. Intangible cultural heritage tourism and place construction. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, I. The Quest of the Folk: Anti Modernism and Cultural Selection in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia; McGill-Queens University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J. Government advertising and the creation of national myths: The Canadian case. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2003, 8, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palmer, C. From Theory to Practice. Experiencing the nation in everyday life. J. Mater. Cult. 1998, 3, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie-Short, J. Imagined Country: Society, Culture and Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, H. The Idea of Nationalism; Macmillian: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. Imagined Communities; Verso Books: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; New York Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Research on Taiwan Youth’s National Identity under the Background of Cross-Strait Exchanges. Taiwan Stud. 2014, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Meinig, D.W. Symbolic Landscapes. In The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes; Meinig, D.W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 164–192. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C. Christianity, Englishness and the southern English countryside: A study of the work of H.J. Massingham. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2002, 3, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raivo, P.J. The peculiar touch of the East: Reading the post-war landscapes of the Finnish Orthodox Church. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2002, 3, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.C. Where geography and history meet: Heritage tourism and the big house in Ireland. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1996, 86, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.C. Heritage and Geography. In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research; Waterton, E., Waston, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dinnie, E.; Blackstock, K.L.; Dilley, R. Landscapes of challenge and change: Contested views of the Cairngorms National Park. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, N. Strategic planning and place branding in a World Heritage cultural landscape: A case study of the English Lake District, UK. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1291–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aide, B.; Hall, C.; Prayag, G. World Heritage as a placebo brand: A comparative analysis of three sites and marketing implications. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, N. Landscape and Branding: The Promotion and Production of Place; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.; Halfpenny, E. Communicating the World Heritage brand: Visitor awareness of UNESCO’s World Heritage symbols and the implications for sites, stakeholders and sustainable management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 768–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. Analysis of the meaning of the terms “nation” and “nation-building” in national construction: Aggregation and collapse—on the construction of national identity in multi-ethnic countries. Res. United Front. 2020, 3, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D. The Ethnic Origins of Nations; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D. Prospect, perspective and the evolution of the landscape idea. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1985, 10, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finell, E.; Liebkind, K. National symbols and distinctiveness: Rhetorical strategies in creating distinct national identities. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, J.W.; Godfrey, M.G. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln football: A metaphorical, symbolic and ritualistic community event. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2011, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cerulo, K. Identity Designs: Sights and Sounds of a Nation; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life; New York Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hosbsbawm, E. The Invention of Tradition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zelinsky, W. Along the frontiers of name geography. Prof. Geogr. 1997, 49, 465–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuncui, Y. The critical toponymy: A dialogue of nation, place and ethnic group. J. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 68, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Alderman, D.H. Focus Section: Women in geography in the 21st century: A street fit for a king: Naming place and commemoration in the American South. Prof. Geogr. 2000, 52, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaryahu, M.; Kook, R. Mapping the nation: Street names and Arab-Palestinian identity: Three case studies. Nations Natl. 2002, 8, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Redwood, R.S. From number to name: Symbolic capital, places of memory, and the politics of street renaming in New York City. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2008, 9, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, L.D.; Vuolteenaho, J. Critical Toponymies: The Contested Politics of Place Naming; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Burlington, VT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Redwood, R.S.; Alderman, D.; Azaryahu, M. Geographies of toponymic inscription: New directions in critical place-name studies. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 34, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.M.; Wang, W.P.; Chen, J.; Tao, Z.M.; Fu, Y.Q. Review and prospect of toponymy research since the 1980s. Prog. Geogr. 2016, 35, 910–919. [Google Scholar]

- Alderman, D.H.; Inwood, J. Street naming and the politics of belonging spatial injustices in the toponymic commemoration of Martin Lurther King Jr. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2013, 14, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaryahu, M. The critical turn and beyond: The case of commemorative street naming. ACME Int. E-J. Crit. Geogr. 2011, 10, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Palonen, E. The city-text in post-communist Budapest: Street names, memorials, and the politics of commemoration. GeoJournal 2008, 73, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretan, R.; Matthews, P.W. Popular responses to city-text changes: Street naming and the politics of practicality in a post-socialist martyr city. Area 2016, 48, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, N. Street-naming, tourism development and cultural conflict: The case of the old city of Acre/Akko/Akka. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Irish place names: Post-colonial locations. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1999, 24, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhu, H. Naming and renaming: A critical study on Guangzhou metro stations. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.C. The politics of space in relation to street naming in Taipei city. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 73, 79–105. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Yang, Q.S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, X.J. Cultural and political interpretation of street naming in Changchun during 1800 to 1945: Based on Gramsci’s hegemony theory. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 34, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Feng, D. The politics of place naming: Changing place name and reproduction of meaning for Coonghua hotspring. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 30, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Cheng, L. The culture and politics during the evolution of historical place: Names in Kuan-Chung Plain in the perspective of critical toponymy. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 35, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. The lure of the local: Landscape studies at the end of a troubled century. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2001, 25, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butz, D.A. National symbols as agents of psychological and social change. Political Psychol. 2009, 30, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Wu, L.P.; Yuan, W.C. The relationship of landscape representation power and local culture succession: A case study of landscape changing in old commercial district of Beijing. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 25, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. (Ed.) Representation. Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Light, D. Tourism and toponymy: Commodifying and consuming place names. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of Leisure Class; (revised 2 ed.); Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, J.; Duncan, N. Reading the landscape. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1988, 6, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.K. Chinese Death Rituals in Singapore; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L. No Place, New Place: Death and its Rituals in Urban Asia. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.M.H. Spatial struggles: Post-colonial complex, state disenchantment, and popular reappropriation of space in rural southeast China. J. Asian Stud. 2004, 63, 719–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, C.K.; Kong, L. Religion and modernity: Ritual transformations and the reconstruction of space and time. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2000, 1, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Giraut, F.; Houssay-Holzschuch, M. Place naming as dispositif: Towards a theoretical framework. Geopolitics 2016, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadmon, N. Toponymy and geopolitics: The political use-and misuse-of geographical names. Cartogr. J. 2004, 41, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.M.; Su, X.B. Lost Elegance: Cultural Politics in the landscape evolution of Guangzhou White Swan Hotel. Tour. Trib. 2016, 31, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.B.; Teo, P. The Politics of Heritage Tourism in China: A View from Lijiang; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Foote, K.E.; Azaryahu, M. Sense of Place. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh, B.S.A. Street-naming and nation-building: Toponymic inscriptions of nation-hood in Singapore. Area 1996, 28, 298–307. [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo, S. Commemorative atmospheres: Memorial sites, collective events and the experience of national identity. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2016, 41, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, S. Public ritual and community power: St Patrick’s Day Parades in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1841–1874. Political Geogr. Q. 1989, 8, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connerton, P. How Society Remembers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Murphyao, A.; Black, K. Unsettling settler belonging: (Re)naming and territory making in the Pacific Northwest. Am. Rev. Can. Stud. 2015, 45, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndletyana, M. Changing place names in post-apartheid South Africa: Accounting for the unevenness. Soc. Dyn. 2012, 38, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J. Hong Kong’s Place Name and Local History; Cosmos Books: Hong Kong, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T. A political wirld philosophy in terms of all-under heaven (Tian-xia). Diogenes 2009, 56, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, J.A. Place and political behavior: The geography of Scottish Nationalism. Political Geogr. Q. 1984, 3, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F. Selected Commentaries of Huangling Tourism Commentaries; Northeast Normal University Press: Changchun, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cox K, R. Spaces of Globalization: Reasserting the Power of the Local; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dijknik, G. National Identity and Geopolitical Visions: Maps of Pride and Pain; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bocock, R. Ritual in Industrial Society; Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. The power and limits of branding in national image communication in global society. Int. Political Commun. 2008, 14, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, S. Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mira, I.G. Forging communities: Coalitions, identity symbols and ritual practices in Iron Age Eastern Iberia. World Archaeol. 2015, 48, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harvey, D. Heritage pasts and heritage presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 7, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Automobility and national identity: Representation, geography and driving practice. Theory Cult. Soc. 2004, 21, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, R.; Morgan, N.; Westwood, S. Visiting the trenches: Exploring meanings and motivations in battlefield tourism. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieling, J.; Ong, C.E. Warfare tourism experiences and national identity: The case of Airbone Museum ‘Hartenstein’in Oosterbeek, the Netherlands. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijin, J.; Fricke, M.C. Visitor emotions and behavioral intentions: The case of concentration camp memorial Neuengamme. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yun, H.; Jeong, Y.H. The Keywords and Social Network Analysis of Heritage Tourism Using Big Data. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2021, 25, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, T.; Zheng, X.; Yan, J. Contradictory or aligned? The nexus between authenticity in heritage conservation and heritage tourism and its impact on satisfaction. Habitat Int. 2021, 107, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ranking | Activity | Date of Ceremony | Historical Index | Impact Index | Participation Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Public memorial ceremony in Shaanxi Province | Tomb Sweeping Day | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 2 | Memorial ceremony to worship Yan Emperor in Hunan Province | Double Ninth Festival | 9 | 10 | 9.5 |

| 3 | Global ceremony to worship Confucius in Shandong Province | Mid-Autumn Festival | 10 | 9 | 9.5 |

| 4 | Yellow Emperor memorial ceremony in Henan Province | Lunar 3 March | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| 5 | Ancestor worship ceremony of Yandi in Hubei Province | Lunar 26 April | 8 | 9 | 9.5 |

| Demographic | Items | Frequency (N = 120) % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 65 | 54% |

| Female | 55 | 46% | |

| Age (years) | Under 18 | 19 | 16% |

| 18–30 | 37 | 31% | |

| 31–40 | 22 | 18% | |

| 41–50 | 20 | 17% | |

| Above 50 | 22 | 18% | |

| Education | Below high school | 23 | 27% |

| Junior colleges | 40 | 28% | |

| Undergraduates | 48 | 38% | |

| Graduate or above | 9 | 8% | |

| Occupation | Farmers | 20 | 22% |

| Private business owner | 23 | 20% | |

| Government | 18 | 19% | |

| Education or research | 13 | 13% | |

| Companies | 17 | 14% | |

| Others | 19 | 12% | |

| Degree of familiarity with the Yellow Emperor | Not at all | 5 | 4% |

| A little | 39 | 33% | |

| Medium | 54 | 45% | |

| A lot | 21 | 18% | |

| Regions | Tourists from Mainland China | 75 | 63% |

| Tourists from Taiwan | 45 | 37% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, H.; Yu, Y.; Yuan, Z. Heritage Tourism and Nation-Building: Politics of the Production of Chinese National Identity at the Mausoleum of Yellow Emperor. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148798

Wei H, Yu Y, Yuan Z. Heritage Tourism and Nation-Building: Politics of the Production of Chinese National Identity at the Mausoleum of Yellow Emperor. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148798

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Hongni, Yi Yu, and Zhenjie Yuan. 2022. "Heritage Tourism and Nation-Building: Politics of the Production of Chinese National Identity at the Mausoleum of Yellow Emperor" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148798

APA StyleWei, H., Yu, Y., & Yuan, Z. (2022). Heritage Tourism and Nation-Building: Politics of the Production of Chinese National Identity at the Mausoleum of Yellow Emperor. Sustainability, 14(14), 8798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148798