1. Introduction

“Increasing access to water is essential to achieving health and sustained poverty reduction” [

1]. A major way to do this is by using water to reduce poverty through the scale-up of irrigation systems. Water is a cross-cutting issue that is pivotal to improving the lives of Ghanaians [

1]. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) reports an estimated 1.9 million hectares (Mha) total of potential irrigatable lands in Ghana [

2]. The total water-managed area in the country was projected to be approximately 30,900 hectares (ha) in 2000, of which approximately 90% were actually irrigated. Twenty-two formal irrigation schemes produced 65% of the irrigated ground [

2]. Formal irrigation schemes are primarily funded by the public sector and rely on some form of permanent irrigation infrastructure [

1]. The government intends to eventually increase the total irrigatable area to 500,000 ha or more, thereby increasing the total coverage from 1.7% to 28% of the potential. Ghana is not currently agriculturally independent and seeks to make substantial efforts in the scale-up of irrigation technologies to decrease the country’s importation of agricultural goods from neighboring countries [

1]. A current economic market chain analysis needs to be conducted to identify the limitations to the scale-up and dissemination of irrigation technologies in a value-added commodity market. This should identify where the most promising opportunities for investment can be found.

The present work had two general objectives and one minor goal. The first was to complete a comprehensive literature review on agricultural water supplies in Ghana, focusing on market chain analysis, tracking elements from the access of the resource to the physical delivery of freshwater to the fields. The second was to identify opportunities within the Ghana agro-water sector that might enhance the capabilities for irrigation and increase its use. These two general project goals will have a rapid but declining impact window based on the current relevancy of the information contained in the review. This synthesis of information is of immediate value to the community of scientists, engineers, and technicians working to improve agricultural water access in Ghana, as the bulk of valid information is buried deep within UN and Ghana governmental archives. A third, more extended goal of this study was to provide a long-term roadmap for natural resource specialists needing to establish an initial resource level and socio-political climate survey surrounding their area of interest. This aspect of the work could have a more lasting impact within the realm of human knowledge. Ghana is only one of many ambitious developing countries in the world, straddled with a fragmented and chaotic government oversight apparatus. The description of the adaptive review process to penetrate and access thinly published data about specific natural resources within a small national entity is of significant value to the broader community of economic development specialists working beyond the field of agricultural water and should have technical relevance for a relatively long period of time. The balance of this paper will consist of an initial description of the irrigation sector in Ghana, the methodology and process of this specific literature review, a synthesis of the results from the final accepted materials, a discussion of the implications of this work, and some concluding thoughts about the potential of irrigation in Ghana and the adaptive literature review process in thinly published materials.

2. Structure of Ghana’s Irrigation Sector

Ghana’s irrigation sector is primarily composed of informal (smallholder), formal, and large-scale commercial irrigation sub-sectors [

1], which can be broken down into two types of irrigation classifications: conventional or emerging systems [

3,

4]. The informal irrigation sub-sector is composed of irrigation practiced by an individual who cultivates an area of 0.5 ha or more by using simple structures and equipment for water storage, conveyance, and distribution [

1]. This typically consists of manually fetching water, primarily with watering cans and buckets, but possibly using some motorized pumps and hoses when located near an accessible stream or reservoir. The informal irrigation sub-sector is dependent on seasonal patterns and non-permanent infrastructure. The formal irrigation sub-sector is reliant on some form of permanent irrigation infrastructure and is primarily funded by the public sector. The large-scale commercial irrigation category falls within both the formal and informal sub-sectors, and Lamptey et al. state that “Large-scale commercial irrigation is formal when the government provides the primary headworks, conveyance, and distribution, while the private investor provides secondary distribution, water application, and equipment” [

1]. This type of irrigation falls into the informal sub-sector, when the headwords, infrastructure, and equipment are provided by the private investor. This form of irrigation is primarily focused on the export of fruits and vegetables, with farm sizes ranging between 25 ha and 1000 ha or more [

1].

Conventional irrigation systems are those developed by the Government of Ghana or various non-governmental organizations (NGOs), while emerging systems are those typically initiated by private entrepreneurs and farmers, either privately or with little support from the government and/or NGOs [

3,

5]. Emerging irrigation systems are based-on access to mobile and flexible pumps, which utilize a diverse spectrum of energy sources, such as diesel, petrol, wind, grid-based electricity, and solar electric. Comprehensively, conventional irrigation systems number approximately 10,850, with access to 14,700 ha, of which only 8750 ha (60%) has been fully developed for irrigated farming [

5,

6]. Ghana’s water sources are numerous, consisting of both surface and groundwater resources. As shown in

Table 1, based upon information from Reference [

5], there are eight main types of irrigation systems present within Ghana, with twenty-three sub-types of physical irrigation systems.

Table 1 was originally developed through a brainstorming workshop composed of professionals within the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority (GIDA), International Water Management Institute (IWMI), International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), University of Developmental Studies (UDS), and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) [

5]. This work included a review of reports and data from within these entities and included online publications and a hard copy published reports within Ghana not generally available to common electronic search engines [

5].

Table 1 provides detailed information as to the type of irrigation systems and the components present in each. In general, it should be noted that the irrigation systems identified as ‘conventional’ constitute the larger numbers of current systems, the larger acreage under cultivation, and the bulk of capital currently devoted to improved agricultural water management and utilization in Ghana. The ‘emerging’ category tends to represent the contribution of small shareholders to improving agricultural water utilization by taking advantage of low energy input, specific-site advantaged, or labor-dominated irrigation systems.

3. Methodology of Analysis

As part of the present analysis, a systematic review of the current literature was conducted using the Purdue University Library database search systems. Peer-reviewed technical journals and easily accessible government reports were the primary valid sources identified. From the Purdue library system, 684 databases were used. Unfortunately, the initial number of acceptable returns was fairly low, so the scope of the search was widened to include new, localized Ghana databases of potential interest. These five additional government databases were accessed to increase the reach of the review beyond those the Purdue Library Database search system had initial ready access to. Twenty-one search terms commonly applied to irrigation issues in Ghana were utilized in the electronic search and are listed in

Table 2. It is unfortunate that not all international agencies update their country-specific reports yearly or even every 10 years. This contributes to the sparse data space. The filtering process was initially focused on papers published within the last 5 years, but that was increased to a 20-year time frame, following the continuing extremely light return rate for the expanded database searches. Therefore, in order to include the most current FAO AQUASTAT report for Ghana, the time frame for the search process had to be extended to garner enough material for an effective review, and just short of 200 documents were eventually selected for the preliminary screening. These reports provided insight at the country level on water resources, water use, and agricultural water management and had a specific emphasis on irrigated agriculture in Ghana [

2].

Both the addition of targeted databases likely to hold valid information for the search process and the post initium lengthening of the search window are indicative of a small data space, which is generally best addressed through a systematic literature review. The lack of an appropriate number of literature returns prevented a deeper bibliometric or meta-analysis. In this study, the valid identified sample space was much too small to conduct a meta-analysis. Although there is no exact answer, most effective meta-analysis efforts seem to require about 1000 final, validated sources. The initial return rate for this work was roughly 20% of that size. This was diminished upon further review to roughly 2% of the needed field. Certain bibliometric indices certainly could be calculated for this review, but their ability to provide meaningful results, in this case, is suspect. It is fair to note that within the final selected documents for review, there was a tendency toward metrics indicating co-citation, co-author, co-keyword, and institutional connectivity. However, much of that can adequately be explained by the limited size of the technical community dealing with water resources in Ghana.

The papers selected for a deeper review had to reference Ghana and some water components within the paper title, abstract, or body of the article. Papers not specific to Ghana were not considered for this effort. If the prospective paper referenced Ghana and some water components, though not specific to irrigation, the paper was reviewed and read in full. The papers examined by this study were limited to the articles picked up through the unique search phrases used at the time the research was conducted. Of the papers reviewed, if they did not mention freshwater use in some aspect, the paper was not considered to be relevant for the purposes of this study and was removed from further consideration. The papers deemed to be relevant were only those that specifically focused on using irrigation for agricultural production within Ghana. Examples of a few unique search terms used in this study include: “Ghana irrigation”, “Ghana water systems”, “Ghana water resource management”, “Ghana value chain”, and “Ghana market access.” Eventually, 197 papers were thoroughly read and reviewed from among all of the databases, and 22 papers were found to be pertinent. These were relevant because they focused specifically on water use for irrigation within Ghana. This provided an 11% overall relevancy from the secondary portion of the search filtering process to yield the documents utilized in this paper. Regrettably, very few of the reviewed papers were found to specifically focus on water for the purpose of irrigation management within Ghana, but if the central focus of this study was the understanding of the agricultural water market chain in Ghana, then the inclusive criteria needed to remain fairly tight.

In order to achieve a successful systematic literature review, the scope of relevant search space was enlarged twice.

Table 3 illustrates the adaptive steps followed in this study which finally yielded a minimum number of acceptable sources for review. A traditional electronic review was conducted using the defined search term on the 684 easily accessible and appropriate databases in the Purdue Library System. This effort produced a wholly insufficient number of returns for review. Adding some additional focused databases was suggested, and the primary rate of return was improved by including certain less-commonly accessed Ghana government archives. UN sources were well-represented within the valid hits of the preliminary search, and it was noticed that there was a distinct 10-year periodicity to many of the reoccurring reports. The initial five-year window of relevant applicability was widened to twenty years, and sufficient sources were finally present as an adequate pool of initial review materials. The search realm expansion utilized two adaptive processes, both of which were suggested through an examination of the existing returns and likely potential means to improve the document yield. The only obvious drawbacks to this technique of post initium modification are a tendency to miss any well-hidden sources of information and the potential accusation of research bias in the selection of search modification parameters.

4. Results of the Market Chain Value Analysis and Irrigation Technology Review

From the 22 final selected works, the structure of Ghana’s irrigation value chain network was confirmed, along with its current access and availability to irrigation resources. The current strengths of various value chain actors were determined, and their role within the value chain and potential opportunities for Ghana to improve within the current structure were reviewed. Primary vertical and horizontal linkages and constraints to the scale-up and increased adoption of irrigation systems within the country were identified. Constraints were delineated and summarized into four main areas that were proven crucial to the current scale-up of irrigation systems. Five major competitive opportunities, groundwater development, water lifting technologies, small reservoirs and dugouts, development of lowland/inland valleys irrigation, and innovative institution arrangements, such as out-grower schemes, appear to be the most competitive opportunities for improving the value chain in the irrigation sector in Ghana [

7].

4.1. Current Access and Availability of Water Resources

Ghana has potential access to significant water resources. However, across the country, this water access is not uniform [

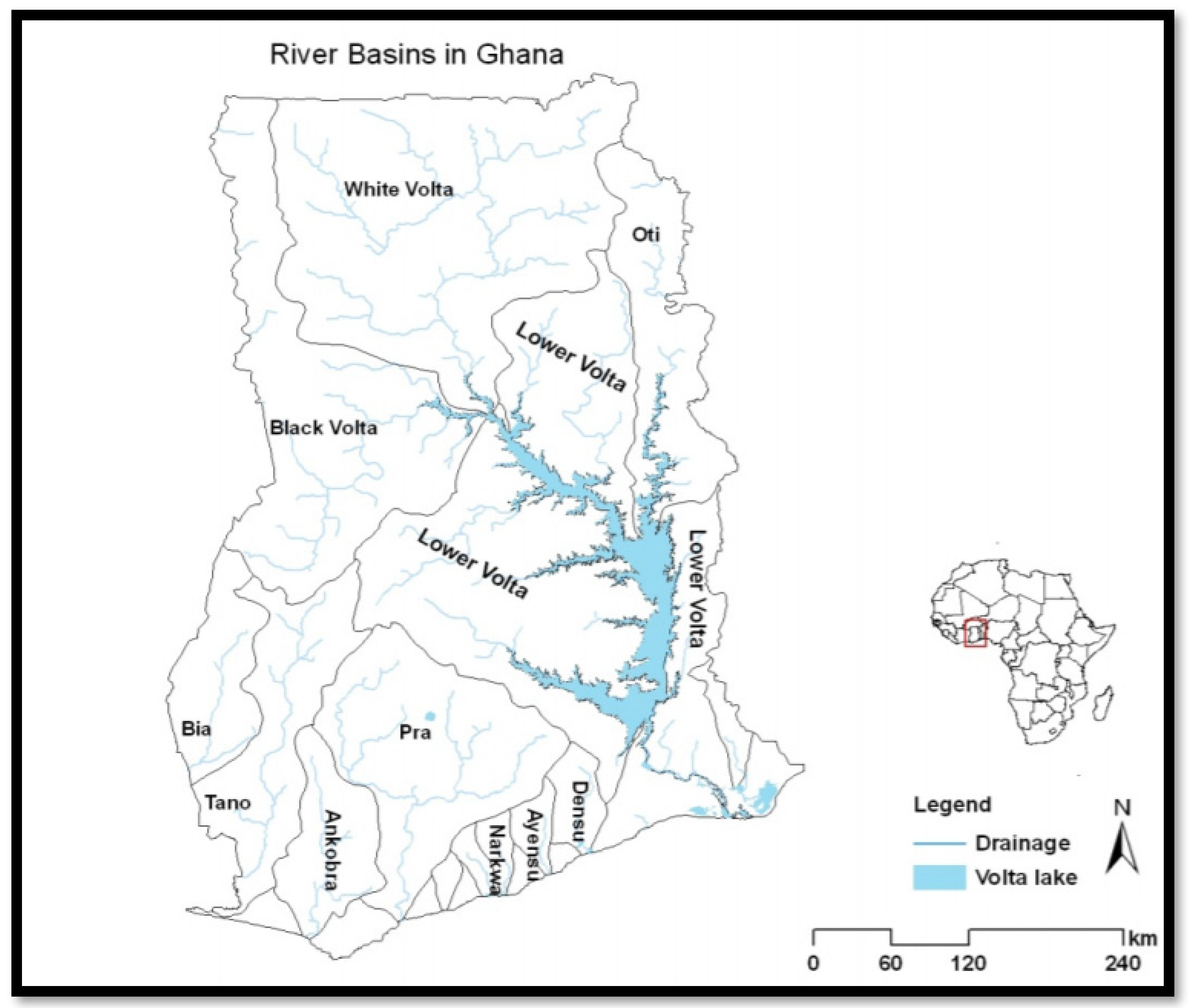

3]. The country’s river basins are displayed in

Figure 1 [

4]. Ghana’s rivers drain south towards the Gulf of Guinea, and the Volta River catchment area accounts for nearly 70% of the country’s landmass, with the remaining 30% of rivers in the south and southwestern portion of the country directly into the Gulf [

8]. The Volta River basin is shared with Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Togo, Benin, and Mali. The major sub-basins of the Volta include the Black and White Volta Rivers, the Oti River, the Lower Volta, and Lake Volta. Impoundments and reservoirs for hydro-electric power generation, water supply, and irrigation exist. The largest is the Akosombo hydro dam, which is located 100 km from the mouth of the Volta. It was constructed in 1964 and covered an area of 8300 km

2. A small impoundment downstream of the Akosombo dam covers an approximate area of 40 km

2. Two other additional impoundments are the Weija and Owabi Reservoirs on the rivers Densu and Offin [

8]. The only significant freshwater lake in Ghana is Lake Bosomtwe, located within an impact crater in the Ashanti region of Ghana.

Ghana’s groundwater aquifers are normally between 10 m and 60 m in-depth, and well yields rarely exceed 6 m

3/h [

8]. In the southeastern and western portions of the country, aquifer depths vary between 6 m and 120 m. In areas where limestone is present within the soil profile, aquifer yields have been reported as high as 180 m

3/h. Although some pollution and illegal mining occur within the country, the overall quality of groundwater is good, despite these points of concern. High mineral levels can occur, and some groundwater may include iron, fluoride, and other minerals. Along the coast, salinity and saltwater intrusion can be an issue. Through the strong efforts of both NGOs and various Ghana government agencies, more than 10,000 boreholes exist throughout the country. However, these are not primarily used for irrigation; rather, they are utilized for household drinking and domestic water needs within local communities [

8].

Ghana receives, on average, annual precipitation of 283.2 billion m

3 (BCM) [

2,

4,

5]. The total actual renewable water resources are reported to be 53.2 BCM per year, with the country’s total actual withdrawal of 982 million m

3 (MCM). Of the water withdrawn, 235

MCM is for domestic purposes, 95 MCM for industrial activity, and 652 MCM for irrigation. The country’s total water withdrawal as a percentage of total available renewable water resources is only 1.8%, and of this tiny amount, 66% is withdrawn for the purpose of irrigation [

2,

4,

5]. This indicates that, if well-managed, the country’s precipitation, surface water, and largely untapped groundwater resources are wholly sufficient to meet most projected domestic and irrigation water needs [

9].

Agriculture within Ghana accounts for 37% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and employs approximately 56% of the total economically active population [

5]. Of Ghana’s total agricultural land area, only 39% is cultivated [

5]. The country is primarily dependent on rainfed agriculture, especially in the northern regions [

9]. Seasonal variability of rainfall is adequate during most years for the production of major staple food crops, but it can lead to food insecurity on a widespread scale during severe drought years [

9]. Crops cultivated under irrigation include rice and vegetables, such as tomatoes, okra, cabbage, and spring onions. Rice accounts for approximately 40% of irrigated ground, and the remaining 60% is focused on vegetables [

5]. Local rice production has been unable to keep up with the increasing consumption within the country to the extent that Ghana now relies on importing 70% of its domestic rice consumption [

4]. In order to decrease the country’s dependency on imports, Ghana’s Ministry of Food and Agriculture strongly desires to encourage and increase the cultivation of domestic rice and vegetable production through irrigation [

4].

4.2. Irrigation Equipment within the Ghanaian Value Chain

Ghana’s access to irrigation equipment is irregular. Some farmers purchase equipment from outside of Ghana, but most obtain their machinery from the bigger city agro-dealers [

10,

11]. In Ghana, there are approximately 1500 agro-dealers operating 3500 agro-input sales points [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Most farmers are aware of motorized pumps and water-lifting technologies, but they cannot utilize them because they cannot afford them [

9,

10]. Those that have access to these technologies are generally “better-off farmers,” meaning those in the top 20% in terms of income. Therefore, the majority of small farmers are currently using hand-watering methods, such as buckets and watering cans, but they would likely prefer to use a motorized pump if sufficient resources were available [

9]. All motorized pumps in Ghana are imported because Ghana has no in-country pump manufacturers.

Due to this circumstance, the purchase price of water pumps varies greatly [

11]. Agro-dealers are generally limited in the types and sizes of pumps offered. The most common brands are Honda (77%) for petrol- and diesel-powered units and Sears for electric pumps (59%). The petrol pumps range from 1.86 to 4.10 kW, while 95% of the electric pumps range between 0.75–1.49 kW. “Pumps that are generally on sale are of sub-standard quality. They break down quickly due to minor defects and are rapidly scrapped” [

11]. Poorly-developed supply chains can, unfortunately, lead to high taxes within the sector, high import fees, high transaction costs, and a general lack of knowledge with regard to technical design within the field [

9]. Irrigation pumps are meant to be taxed except in Ghana from the port on arrival, but the clearing process is lengthy and not well-defined, which can lead to additional hidden costs of 5–8%. The commercial distribution network for irrigation equipment in Ghana is not well-developed, regrettably dampening some of the competitive effects of a market economy [

11].

4.3. The Strengths of the Market Chain Actors and Linkages

Ghana’s irrigation policy and strategy for its implementation have been primarily designed by government agencies with the intent of promoting both public and private irrigation development having specific linkages to the agricultural sector.

Figure 2 shows the linkages between the various market chain actors. The most influential political actor is the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority (GIDA). The GIDA is part of the Ghana Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA). All in-country actors are influenced by the GIDA through policy implementation. GIDA works with regulatory agencies, such as the Water Resource Commission (WRC) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), to enact and shape irrigation policy, requirements, and standards. The district assemblies (DAs) are the face of GIDA and MOFA within communities. The DAs conduct training, workshops, dissemination, and extension services for those residents of their respective districts. Service providers at the local level include consultants, contractors, support services, financial institutions, and the private sector. Both service providers and irrigators are overseen by their perspective DA and can take advantage of services offered by the DAs. Although perhaps difficult to accept from a Western perspective of minimizing potential conflicts of interest, many agricultural extension agents, in addition to their government extension responsibilities, have their own agro-businesses to assist them in generating additional income. Therefore, extension agents can also act as agro-dealers to both irrigators and service providers through the sale of agricultural products and equipment that their businesses might offer. Water User Associations (WUA) are another potential path of smallholder access to irrigation, and they are typically defined as a collective group of farmers that come together to manage a communally shared irrigation infrastructure or freshwater access resource. It is the intention of GIDA to work through the DAs, regulatory agencies, and WUA cooperatives to foster capacity building and improve any pre-existing systems [

1]. This collaboration is the primary route that GIDA is using to stimulate the desired 500,000 ha of irrigated area in the medium to long term [

1].

Both the private sector and financial institutions have vertical linkages to the DAs [

1]. Service providers also link with Irrigators and Research and Academic Institutions by offering various services. Financing institutions include the Ghana Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MOFEP) and international development partners, such as NGOs and aid agencies. Specific examples of active development partners include the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), International Fund for Agricultural Development of the United Nations (IFAD), Canada International Development Agency (CIDA), World Bank, African Development Bank (AfDB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) [

1]. These financing institutions work with GIDA to provide lines of credit for the development of irrigation systems, larger project funding involving irrigation, and joint partnerships on approved programming within Ghana. The GIDA representatives at the DA level then provide and implement programming and training efforts to potential irrigators within their respective districts.

Research and academic actors within Ghana include the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), the University of Cape Coast (UCC), the University of Ghana (UG), the University of Development Studies (UDS), IWMI, and the various branches of the Council of Scientific Industrial Research (CSIR). Additional service providers within the supply chain include consultants, expatriate firms, contractors, and support service organizations [

1]. Research and academic institutions and service providers are linked vertically with the financing institutions. This complex organizational cross-linkage matrix can inadvertently conspire to limit access for those outside the network to the information published for in-network distribution and use.

4.4. Constraints

Irrigation systems in Ghana are classified into conventional and emerging irrigation systems. Each of these types of systems is hindered in adoption and operation by unique local constraints that could result in the bottle-necking and hindrance of irrigation technology scale-up within the Ghanaian market chain [

4,

7,

13]. Based on the current review of the literature, these various constraints have been summarized into four categories: Policy and Institutions, Costs and Financing, Infrastructure, and Biophysical. These issues, drawn from References [

4,

7,

13], are summarized in

Table 4.

Of those constraints identified, land tenure, access to credit and extension services, and a lack of adequate infrastructure within the sector are the greatest hindrances to growth potential [

4,

7,

13]. Costs are generally high for the development of irrigation systems within the country. With the majority of the country being flat, gravity-fed water systems are not typically suitable, and therefore, motorized pumps are essential [

4]. Due to this circumstance, both the cost of fuel and capital investment required to purchase motor pumps are among the key impediments for smallholder irrigators [

13]. Balana et al. state that “Improving credit access and considering alternative energy options (i.e., solar pumps) could increase small scale irrigation technology adoption and improve household incomes and nutrition” [

13]. Many of the constraints to adaptation are focused specifically around cost support, which indicates that within the irrigation sector, there is ample room for improvements, particularly on the affordability, access, and economic elements.

4.5. Competitive Opportunities within the Irrigation Sector

The results from this market value analysis found five significant types of opportunities within the irrigation sector of Ghana. These areas are the development of groundwater, the adoption of water lifting technologies, the design and installation of small reservoirs and dugouts, the design and adoption of lowland/inland valley irrigation systems, and the implementation of innovative institutional arrangements.

4.5.1. Groundwater Development

Significant potential lies in further accessing groundwater for irrigation through both shallow and deep groundwater wells utilizing different drilling and pumping techniques [

7]. Of the total groundwater consumed in Ghana, only 5% is used for agriculture. One-third of smallholder farmers in the Volta, Upper East, Upper West, and the Greater Accra regions access shallow groundwater, but multiple constraints have hindered further growth. Farmers utilizing groundwater typically use buckets for irrigation, and this is very labor-intensive. The cost of developing shallow groundwater for irrigation is relatively low and could be used during dry-season farming to produce vegetable crops that could potentially provide good returns to smallholder farmers.

Currently, there are no specific policies with regard to groundwater withdrawal or the installation of water pumping equipment, and therefore, a combination of supportive, informative policy and a better understanding of hydro-geological data as to the specific location of the needed water are necessary for growth. “Further limitations (to development) include high labor requirements for the installation and digging of wells, high energy costs for pumping, unequal access to affordable quality pumps, advice, credit, and market accessibility” [

4,

14]. Groundwater use is the highest in the Volta Region, predominately due to the presence of Lake Volta and its river network system. Shallow water wells are more easily accessible when they are closer to stream networks due to the higher water table, and there are successful, low-cost strategies to access shallow water [

15]. Access to appropriate water management technologies is more varied in the Volta Region than in others. Both electric pumps and petrol/diesel pumps are reported to be used by local farmers. In order to increase groundwater usage, better information with regard to where groundwater can be found and easily accessed is clearly needed, as little documentation of existing groundwater resources exists. The addition of a simple well registry would reduce the cost of drilling and pumping and decrease the risk of not hitting the water in the surrounding countryside. The development of easily accessible groundwater maps, improving knowledge of groundwater availability and use, the development of explicit irrigation policy and strategies per district, and the retention of extension services personnel trained in groundwater irrigation issues, agronomic information, and irrigation schedules based on crop types, would all yield significant improvements in expanding groundwater access [

4,

14].

4.5.2. Water Lifting Technologies

In order to be successful in Ghana, water-lifting technologies must be affordable and oriented toward a variety of customers: smallholders, individually or at the community level, and large-scale commercial farmers [

7]. Utilizing water-lifting technologies, such as motorized pumps, would allow farmers to grow more economically advantaged vegetables and attain higher yields during the dry season than those who only utilize buckets for irrigation. According to References [

5,

15], it is estimated that of the 1.85 million farm households in Ghana, only 12% own a pump for the purpose of irrigation. Those that have access to water-lifting technologies primarily use them for growing vegetables. Most farmers either buy pumps from outside the country or rent them from their neighbors. To finance such a purchase, most farmers either use their own funds or borrow from informal sources. A beginning industry of irrigation service providers does exist, and they may eventually provide a stable means for farmers to access lifting technology through rental rather than direct ownership. However, at the present time, this is an underutilized technique of providing water access. A large network of motor pump dealers is also present in Ghana, but the quality and sustainability of some of the imported technology are questionable [

7]. More numerous and better quality pumps are needed in the more rural areas of the country, and the major constraints against the adoption of motorized pumps are primarily a lack of viable financing options, an inadequate supply of pumps, unreliable water sources, and high labor costs [

7]. There are multiple simple measures that could greatly improve the current situation. Communicating the benefits of water-lifting technologies through on-farm demonstration days and mass media content could provide an extension-type practitioner education package that could illustrate the benefits of irrigation technology. Conducting pump training workshops with farmers on pump selection and maintenance, crop selection, agronomic practices, post-harvest crop handling, and the marketing of produce would also help. Improving the supply chain of pumps through the creation of pump industry registries, including current importers, dealers, and retailers, would also be a positive step. Additionally, incorporating basic technical training on irrigation pumps into agricultural school syllabi and providing access to affordable loans on reasonable terms would all be simple measures that could have a positive impact on the quality of life for numerous people in Ghana [

3,

5,

15,

16].

4.5.3. Small Reservoirs and Dugouts

The term ‘small reservoir’ refers to water stored behind an earthen or cement dam that is less than 7.5 m in height. These are generally capable of storing up to 1 MCM of water and can sometimes supply a potential downstream irrigation area of up to 50 ha. A well-designed reservoir can sustain multiple endeavors: livestock, fisheries, domestic needs, small businesses, support soil and water conservation, and the prevention of drought-related effects within the local communities during rainfall shortages. The financial investment is generally high for such endeavors to be private, and they are typically externally driven and communally managed. Many times, external funds are provided through governments, donors, and NGOs [

17,

18]. Small reservoirs and dugouts have the opportunity to be managed at both the smallholder level, individually, or at the commercial level [

7]. When these structures are considered for the purposes of irrigation, most installations perform below expectations. However, small reservoirs can provide additional benefits to the local community that are often unaccounted for. Fishing, recreation, and improved quality of life generally result from open access to nearby surface waters.

4.5.4. Lowland/Inland Valley Irrigation

Ghana has vast areas of land suitable for inland valley irrigation that are not currently under cultivation [

4,

9]. The inland valleys and lowland valleys occupy 12% of Ghana’s land area but represent a disproportionately smaller amount of agricultural production [

2,

19]. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization in Reference [

20], estimates that an average potential of 990,000 Mha of additional land is suitable for development in this region due to the ease of water access, the availability of water during the wet season, the soil moisture during the dry season, the fertility of the soil, and the catchment topography. Increasing rice production and improving surface water management in the inland valleys has the potential to increase profitability for smallholder farmers and increase in-country rice production at the same time. This is a major priority for the current Government of Ghana, which seeks to scale up rice production within the country, meeting the growing in-country demand, reducing dependency on imports, and contributing to poverty reduction. Inland valley irrigation expansion is a low-cost, high-potential, high-return opportunity for irrigation-based economic development.

4.5.5. Innovative institutional arrangements

Opportunities exist to access water for domestic agricultural production and for export markets through the utilization of innovative institutional arrangements, such as out-grower schemes and public-private partnerships [

7]. Out-grower schemes provide a guaranteed market for smallholder farmers. Many multinational agribusinesses and large supermarket chains are turning to out-grower organizations to secure a portion of their supplies. Often, these businesses offer participating benefits to farmers such as water access, irrigation technologies, material inputs, and extension services. In return, the farmer agrees to sell their produce to the company at a guaranteed fixed price and then normally pays a percentage of this to cover their cost of participating company benefits. Out-grower schemes offer many benefits to smallholders: a guaranteed market, access to inputs, hybrid seed, credit, water, technologies, machinery and equipment, risk minimization through the pooling of resources, and cost-sharing. The primary challenges with regard to out-grower schemes can be boiled-down to issues of trust, information, costs, and incentives. The most successful schemes are those with direct benefits to both farmers and the companies, along with indirect benefits to the local region resulting in economic growth and job creation for the local area. There must be some level of trust between the company and the smallholder so that the company can afford to take the risk of working with the smallholders. Likewise, trust in bigger companies by small farmers must increase, so they can get over their discomfort at working with larger companies and access a broader array of potentially useful technical tools. Working through farmer cooperatives and allowing the cooperative leadership with more applicable experiences to negotiate on behalf of farmers could also help improve the trust problem. Smallholders can lack access to market information, limiting their ability to negotiate during commodity and supply contracting effectively. Dealing with a large number of smallholder farmers can also lead to higher transaction costs for a company, particularly if farmers come from distant and more isolated areas. These issues can be overcome by utilizing networks of farmer agents and mobile phones to assist with communication. Public investors can help the government to provide the necessary legal and institutional frameworks to enhance industry transparency and clarify the benefits and responsibilities of contractual obligations, thereby supporting farmers. Such groups can also assist in ensuring that farmers’ interests are valued and met under the resulting arrangements [

3,

21,

22].

5. Discussion

Results directly summarized from the individual articles were presented previously, and therefore, the focus of this section is on identifying what structural improvements could be implemented by governmental policymakers to improve the efficiency of irrigation systems within Ghana and enhance their reach within the agricultural sector.

5.1. Study Limitations

The results of this study were limited to articles that were accessible through electronic means and published in English. The resources utilized were those accessible through the Purdue University library system and Ghanaian government databases. It should be noted that the results obtained through the Ghanaian government databases are those accessible to both non-Ghanaian and non-government individuals, but they do not necessarily comprise the entirety of the documents that might have proven useful. The adaptive literature review process could have been extended further to incorporate more sources, but most literature reviews proceed from initially defined parameters to avoid the potential implications of researcher bias or ‘steering’. This element is unavoidable in an adaptive review, where the search criteria remain fluid and in flux. As well, most literature reviews are focused on articles published within the last five years. This also proved untenable for the current effort, as many of the potential sources of information on this specific subject were only rarely updated.

5.2. Irrigation Opportunities

With the agricultural sector employing 56% of the total economically active population in Ghana, improving any component of the sector has the potential to impact millions [

5]. Ghana has access to significant water resources, and these are sufficient to meet most of the projected domestic and irrigation water needs [

3,

9]. Ghana’s land cultivation is only 38.9% of its potential, indicating that there is significant expansion potential for irrigated agricultural production [

5]. The idle land and water resources within the country could be utilized to develop significant agricultural production through the use of irrigation systems.

The irrigation supply chains to access needed equipment are poorly developed in-country, and these require significant improvement [

9]. The confusing customs-clearing process at the port of entry needs to be streamlined and better defined, helping to eliminate the hidden costs that consumers are generally unaware of [

11]. These input tariffs should be fixed, transparent, and enforced consistently to decrease confusion and build consumer confidence in a market economy [

11]. A formal pump and agro-dealer registry should be created, which needs to include import dealers and retailers [

3,

5,

15,

16]. An in-country irrigation pump manufacturer is also desperately needed to decrease the country’s dependence on cheap, sub-standard, imported irrigation pumps [

10,

11]. A goal of the current administration should be to develop an irrigation pump manufacturing facility, or at minimum, an assembly plant within Ghana. Policymakers should consider attracting an international private company or consortium that sees the potential market and opportunity to be found in Ghana. Locating in Ghana could potentially provide ease of access to expanding production and sales within the neighboring Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Care should be taken in choosing the location of this facility, given that the few current general manufacturing plants in Ghana are located in the Greater Accra area. Rural consumers in Ghana are mostly interested in purchasing irrigation pumps sourced from within the upper two-thirds of the country, so a location in Kumasi would be preferable to a southern location, such as Accra. The current cost of developing irrigation systems is high due to expensive imported equipment prices and a lack of in-country options. An in-country pump manufacturer could offset this. Improved access to credit lines would also help farmers in financing such purchases [

13].

Ghana’s groundwater resources should be further developed, especially when the cost of developing shallow groundwater resources is relatively low, compared to other alternatives [

4,

14]. Specific policies should be created with respect to groundwater withdrawal and pumping equipment installation since no record keeping exists now. This should be incorporated into a national irrigation strategy and further tailored by the district. In order to improve access to groundwater, hydro-geology maps for the country should be developed. Extension service personnel need to be trained with regard to groundwater irrigation issues. This should be facilitated at regional levels and further reinforced and disseminated at the district levels. In order to increase the adoption of water lifting technologies, the economic benefits must be clearly communicated to the end users through a mass media effort and extension-based workshops.

For the development of small reservoirs and dugouts and for enhancing lowland/inland valley irrigation, innovative institutional arrangements should be considered to increase the affordability and financing options for these bigger projects [

4,

9,

17,

18]. These projects should integrate multiple users during the design phase and location determination. Existing extension personnel competency regarding the use of these structures is practically non-existent; therefore, lessons on this material should be incorporated into workshop programming for extension officer professional development [

4,

9,

17,

18]. Improvements in the use and efficiency of small reservoirs and dugouts should be focused on better planning and improved operational management [

17,

18]. A stepwise approach should be recommended during the design and implementation process that incorporates all affected parties. Guidelines for contractors on the design of lowland/inland valleys and dugouts should be streamlined and made available [

17,

18]. Lowland/inland valley irrigation projects should be focused on supplementary irrigation between the two rainy seasons, and in the northern areas, the focus should be on full irrigation development [

4,

9]. Developing out-grower schemes would be a great step forward in aiding smallholder farmers to receive a consistent, guaranteed market price for their produce [

3,

21,

22]. Continued development in fostering public-private partnerships would help in moving irrigation development forward in Ghana, and government policymakers have both a strong influence on the activity and an obligation to initiate positive action [

3,

21,

22].

5.3. The Adaptive Literature Review Process

The adaptive process used in this study to enhance the number of relevant literature returns for review and processing was successful. During the initial expansion, further search terms were considered but were not added, as it was felt that the preliminary keyword list was sufficient. Although this would typically be the first parameter to be widened, the beginning search terms were believed to be comprehensive for this study. The expansion of the search term list can introduce further researcher bias into the review in the same manner as the original selection of the search term list, perhaps more so since the researcher will be attempting to broaden the sweep of the search. Significant care must be taken during this process, particularly as the most likely relevant terms were probably contained within the original list. The database expansion in this study made logical sense, and the increased returns from examining the available Ghana government files were measurable. This process also illustrated a significant issue associated with thinly published material. It is extremely likely that there are useful materials buried within the Ghana government directories that could have been helpful but were unavailable. Including additional databases for screening is a viable strategy only if the likelihood of finding relevant information is encouraging. Simply looking in additional databases at random is not a productive activity, and search database expansion should be carefully considered before the expenditure of additional resources. Finally, the relevance of documents depending upon their age must be carefully evaluated before expanding the search window. The devaluation of most information with age creates a situation where the marginal improvement in returns by expanding the search window is balanced by the declining relevance of the material found. Caution should be exercised before expanding the window too far into the past. In spite of these concerns, the outcome of the adaptive literature review for this project can be considered successful. A general view of the agro-water sector of the economy in Ghana was developed, and enough confidence was provided by the results to draw several practical conclusions and recommendations.

The present analyses should provide significant help to the government, non-governmental organizations, and aid agencies working to improve agricultural productivity throughout Ghana via the scale-up of irrigation systems. The process developed in this study to create a large enough search space for an acceptable literature review could have a reasonable utility beyond this specific work on the agro-water sector in Ghana. Working with the adaptive literature review process constraints provided several insights and cautionary elements. This work acknowledges those issues and offers the following thoughts on the process:

Search terms are the most vital element of the process and must be selected with care. Caution should be exercised in expanding the search term list beyond the initial one due to the increased chance of introducing further researcher bias.

Database additions should be considered only when the potential new archival information is likely to be focused on the subject at hand. Resources can quickly be expended in an unproductive manner by blindly adding irrelevant databases.

Search window expansions are somewhat useful, but they only provide limited additional relevant information due to the timeliness factor associated with technical information.

6. Conclusions

This study addressed two primary research goals. A comprehensive review of the agro-water sector in Ghana was completed. Ghana’s irrigation sector is complex and evolving. The following general points can be gleaned from the current literature published on this sector of the agricultural community within the country:

Ghana’s irrigation sectors can be conveniently divided into informal (smallholder), formal, and large-scale commercial irrigation systems.

Conventional and emerging techniques comprise most of the current activity.

The irrigation capabilities within the country are vastly underdeveloped.

Ghana’s access to surface and groundwater resources provides ample potential for development.

Access to irrigation equipment is primarily through import.

Irrigation system components can be purchased from agro-dealers within the country, but the availability and quality of equipment is not consistent throughout the country.

Poorly developed supply chains are causing unequal access and preventing the adoption of best-practice irrigation systems within the country.

Ghana has multiple actors within the supply chain that are seeking to improve the irrigation sector, with GIDA primarily focused on achieving this through public and private irrigation development linkages.

Constraints to both emerging and conventional irrigation systems are focused on the following areas: policies and institutions, costs and financing, infrastructure, and biophysical.

Groundwater development, water lifting technologies, small reservoirs and dugouts, development of lowland/inland valleys irrigation, and innovative institution arrangements, including out-grower schemes, are currently the most compelling opportunities for improving the irrigation value chain within the country.

The implications of these findings from the systematic literature review of agricultural water systems in Ghana suggested several potential policy modifications and enhancements that might improve the general state of affairs. If carried out, these recommendations could assist policymakers and market chain actors in taking advantage of these prospects. The GIDA is the foremost influencer in the agro-water space, and they should:

Work with the other pertinent ministries to clearly define the port clearing process associated with irrigation pumps and make all associated fees transparent and fixed to build consumer confidence.

Create a national registry of formal pumps and agro-dealers so that equipment is more visible and attainable.

Consider attracting an international private company or consortium to develop an irrigation pump manufacturing facility or assembly plant in Ghana to decrease the importation of cheap pumps and dependency on imports.

Develop specific policies with respect to groundwater withdrawal and installation of pumping equipment.

Continue to develop out-grower schemes to provide smallholder farmers a guaranteed market price for their crops.

Incorporate into the extension service training materials the following topics: groundwater irrigation, small reservoirs and dugouts, and lowland/inland valley irrigation.

Encourage local research and academic institutions to develop groundwater hydro-geology maps for the country to increase knowledge of where groundwater is and at what depth.

Partner with the EPA and WRC to create guidelines and standards for contractors designing small reservoirs and dugouts and improving lowland/inland valley irrigation systems.

In general, continue to foster public-private partnerships within the country to move irrigation development forward.

This review of published work should aid agricultural practitioners hoping to begin work in the agro-water sector in Ghana. Government officials should find the suggestions for policy implementation useful, and other researchers in similarly thinly published areas may obtain some guidance from this experience. Combined, the goals of this project should not only improve the state of irrigation technology in Ghana, but they could also potentially assist others in navigating through thinly published technical material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.B.; methodology, G.L.B.; software, G.L.B.; validation, G.L.B.; formal analysis, G.L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.B.; writing—review and editing, G.L.B. and R.M.S.III; visualization, G.L.B.; supervision, R.M.S.III; project administration, R.M.S.III. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as the study did not involve humans or animal subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve humans and required no informed consent documents to be collected.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not produce any new data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Deb Baldwin for her assistance in editing this work and Elvis Kan-uge for providing cultural insight and revisions regarding the initial study. The professional staff of the International Food Policy Research Institute, the International Water Management Institute, and the Ghana Ministry of Food and Agriculture are acknowledged for their gracious use of previously published materials. This research did not receive any specific grant resources of any kind from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. However, the assistance of the Purdue University Agricultural and Biological Engineering department is gratefully acknowledged for its support over the years with graduate teaching assistanceships and faculty salaries. Finally, the authors wish to thank the reviewers and journal editors for their gracious contribution of time and effort to improve this manuscript and ensure its publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AfDB | African Development Bank |

| BCM | billion cubic meters |

| CIDA | Canada International Development Agency |

| CSIR | Council of Scientific Industrial Research |

| DAs | District Assemblies |

| ECOWAS | Economic Community of West African States |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GIDA | Ghana Irrigation Development Authority |

| ha | hectare |

| IFAD | International Fund for Agricultural Development of the United Nations |

| IFPRI | International Food Policy Research institute |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IWMI | International Water Management Institute |

| JICA | Japan International Cooperation Agency |

| KNUST | Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology |

| km2 | square kilometer |

| kW | kilowatt |

| m | meter |

| m3/h | cubic meters per hour |

| Mha | million hectares |

| MCM | million cubic meters |

| MOFA | Ghana Ministry of Food and Agriculture |

| MOFEP | Ghana Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| UCC | University of Cape Coast |

| UDS | University of Development Studies (UDS) |

| UG | University of Ghana |

| WRC | Water Resource Commission |

| WUA | Water User Associations |

References

- Lamptey, D.; Nyamdi, B.; Minta, A. National Irrigation Policy, Strategies, and Regulatory Measures; Ghanaian Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA): Accra, Ghana, 2011; pp. 1–37. ISBN 016031101213.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). AQUASTAT Country Profile—Ghana; United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2005; Available online: https://www.fao.org /3/i9749en/I9749EN.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Diitoh, S. Assessment of Farmer-Led Irrigation Development in Ghana. 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35796 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Namara, R.E.; Horowitz, L.; Nyamadi, B.; Barry, B. Irrigation Developments in Ghana: Past Experiences, Emerging Opportunities, and Future Directions; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/FullReport_228.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Namara, R.E.; Horowitz, L.; Kolavalli, S.; Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G.; Dawuni, B.N.; Barry, B.; Giordano, M. Typology of Irrigation Systems in Ghana; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2010; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency. The Study on the Promotion of Domestic Rice in the Republic of Ghana; Ghanaian Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA): Accra, Ghana, 2008. Available online: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/11900 487_01.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Evans, A.E.; Giordono, M.; Clayton, T. Investing in Agricultural Water Management to Benefit Smallholder Farmers in Ghana; IWMI Working Paper 147; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2012; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghanaian Water Resources Commission (WRC). Water Use; Water Resources Commission: Accra, Ghana, 2020; Available online: https://wrc-gh.org/water-resources-management-and-governance/water-use/ (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- AgWater Solutions Project. Inland Valleys in Ghana; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2011; Available online: http://awm-solutions.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/documents/inland-valleys-in-ghana1.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- de Fraiture, C.; Clayton, T. Irrigation Service Providers—A Business Plan: Increasing Access to Water for Smallholders in Sub-Saharan Africa; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2019; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namara, R.E.; Hope, L.; Sarpong, E.O.; de Fraiture, C.; Owusu, D. Adoption patterns and constraints pertaining to small-scale water lifting technologies in Ghana. Agr. Water Manage 2014, 131C, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infrastructure Development Finance Club (IDFC); Ghana Agri-Input Dealers Association (GAIDA); Ghana Agricultural Association Business and Information Center (GAABIC). Directory of Ghana Agri-Input Dealers; Ghana Agricultural Association Business and Information Center (GAABIC): Accra, Ghana, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Balana, B.B.; Bizimana, J.-C.; Richardson, J.W.; Lefore, N.; Adimassu, Z.; Herbst, B.K. Economic and food security effects of small-scale irrigation technologies in northern Ghana. Water Resour. Econ. 2014, 29, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AgWater Solutions Project. Shallow Groundwater in Ghana; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2011; Available online: http://awm-solutions.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/documents/publication-outputs/learning-and-discussion-briefs/shallowgroundwaterghana.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- AgWater Solutions Project. Water Lifting in Ghana; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2011; Available online: http://awm-solutions.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/documents/publication-outputs/learning-and-discussion-briefs/waterliftinginghana.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Mandri-Perrott, C.; Bisbey, J. How to Develop Sustainable Irrigation Projects with Private Sector Participation; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/24034 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Venot, J.-P. Evaluating Small Reservoirs as an Agricultural Water Management Solution; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2011; Available online: http://awm-solutions.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/documents/project-poster1/smallreservoirsposter.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- AgWater Solutions Project. Small Reservoirs in Sub-Saharan Africa; International Water Management Institute (IWMA): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2011; Available online: http://awm-solutions.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2018/10/small-reservoirs-in-sub-saharan-africa.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Otoo, E.; Asubonteng, K.O. Reconnaissance characterization of inland valley in southeastern Ghana. In Proceedings IVC First Scientific Workshop on Characterization of Inland Valley Agro-Ecosystems: A Tool for their Sustainable Use, Bouake, Cote d’Ivoire; Jamin, J.Y., Windmeijer, P.N., Eds.; IVC, WARDA\\\\ADRAO: Bouaké, Côte d’Ivoire, 1995; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Mapping and Assessing the Potential for Investments in Agricultural Water Management: Ghana; United Nations (UN): Rome, Italy, 2012; Available online: https://www.fao.org/docments/card/en/c/cb235c4f-65a3-4c5f-9987-170e35ef0de5/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- AgWater Solutions Project. Outgrower Schemes: A Promising Model for Poor Farmers? International Water Management Institute (IWMA): Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2011; Available online: https://awm-solutions.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2018/10/Cross-Cutting-Outgrowers.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Amevenku, F.K.; Yeboah, K.K.; Obuobie, E. Assessment of Innovative Institutional Arrangements—The Case of ITFC in Ghana; Council for Scientific and Industrial Research—Water Research Institute (CSIR-WRI) & International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Accra, Ghana, 2012; Available online: http://awm-solutions.iwmi.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/documents/publication-outputs/learning-and-discussion-briefs/ghana-outgrowers.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).