1. Introduction

Climate change is a topic of particular importance, being on the agenda of European decision-makers [

1], underpinning many programs and for which significant amounts of money are allocated [

2,

3,

4].

Climate change represents a change in the statistical distribution of weather patterns and takes into account an extended period of time. The first measures to combat the phenomenon were initiated in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 with the signing of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, when 194 countries agreed to take long-term measures to stabilize the concentration of greenhouse gases and prevent dangerous human influence on the climate system [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Five years later, measures to combat climate change were agreed to in Kyoto, where commitments were signed to reduce greenhouse emissions between 2008 and 2012 [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Among the main challenges facing agriculture today are extreme weather events such as drought and floods [

13,

14,

15]. These occur more and more frequently, throughout the world, and farmers must adapt to these changes, but they must also take into account the need to ensure food security as the world’s population grows and to use natural resources sustainably [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Agriculture should not be seen as the main cause of the increase in greenhouse gas emissions, rising temperatures or the increase in the frequency of extreme events but rather as an ally in mitigating climate change, by selecting local crop or livestock varieties that can help reduce the environmental impact of agriculture and also by implementing management practices to conserve soil [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The impact that agriculture will have on climate change mitigation in the future depends to a large extent on the rural policies that are or will be implemented [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Although in recent years the number of holdings has decreased considerably, from 4.485 million holdings in 2002 to 2.887 million holdings registered in 2020, agricultural land fragmentation remains a topical problem characterizing Romanian agriculture [

26,

27,

28]. The high number of agricultural holdings is mainly due to land fragmentation, a phenomenon that started immediately after 1990, when property (including agricultural land) was retroceded to living heirs [

28,

29,

30,

31].

The degree of agricultural training was a weak link in the knowledge of Romanian farmers, which, with the accession to the European Union and its conditions for accessing European funds [

29], forced farmers to train in this area, but nevertheless, the percentage of farmers with higher education is quite low [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Not so long ago, the effects of climate change were viewed with scepticism by rural people [

29], whose main activity is farming, and were more likely to be attributed to folk beliefs (traditions that are sacredly observed and differ from one cultural area to another) [

28,

30].

National research shows that a significant proportion of farmers depend on agricultural subsidies, which determines the continuity of farming for them, so interest in agriculture has increased with Romania’s accession to the European Union and with the increase in farmers’ income determined by the grant of subsidies [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Although Romania’s agricultural potential is huge, the two sectors—agriculture and livestock—are divided and poorly interconnected, and they operate largely independently of each other [

42,

43,

44,

45]. This hinders the development of Romanian agriculture, so agricultural products of plant origin do not provide high added value and are exported in this form [

46,

47].

Association is another bottleneck in Romanian agriculture, wherein farmers avoid cooperating to obtain better prices for inputs, attract EU funds, process production or market their products [

29]. In 2020, there were only 112 agricultural cooperatives, down 48% from the previous year [

30].

The value of agricultural crop production accounts for approximately 65% of the total value of agricultural production in 2020, the value of livestock production for 33% and agricultural services for only 2.3% [

26,

28,

30]. This indicates the profile of Romanian agriculture, which relies mainly on plant-based agriculture for raw material production, without being integrated into the livestock sector, in order to obtain added value [

29].

The export of agricultural products is a basic component of the national economy, such that, out of the total 74.7 billion euros that were the total value of exports in 2021, 8.6% was the value of agricultural products. At the same time, of the total agricultural products, the value of plant products had a share of 84.2%, compared to live animals and animal products, which only constituted 15.8% of the total [

34,

37].

It is therefore important to find out how open Romanian farmers are to the new guidelines set for the implementation of new environmental protection policies and what measures can be taken before they become mandatory. Undoubtedly, farmers are the main beneficiaries of the results of research studies and thus the main actors implementing climate change measures. This study analyzes the awareness of the effects of climate change on agriculture and the measures that should be implemented in this respect from the farmer’s perspective, taking into account the financial and promotional measures supported by the European Union among farmers. Thus, the study tracks the level and openness of farmers regarding future measures that European decision makers will take in the near future.

Many researchers in the field see climate change as the biggest threat, jeopardizing food security as the demand for food grows [

48,

49,

50,

51]. To avoid this problem, the use of fertilizers and pesticides has been called for, but this method involves the use of finite and unsustainable resources [

52,

53,

54]. With this in mind, scientists have begun to place greater emphasis on sustainability and increasing the resilience of crops to climate change [

55,

56].

A survey conducted in major agricultural areas that measures farmers’ awareness of climate change and wastewater use for irrigation shows that farmers with sufficient resources are more able to cope with the negative effects of climate change [

57].

The pressure to adapt is greatest in poor countries, where this capacity faces serious problems [

58,

59]. Some adaptation measures seem easier to implement, building on existing technologies, but others need new technologies or policy reforms to encourage them [

60,

61].

The predictions of climate change are bleak, indicating significant changes in the coming decades that will force people and communities to respond. Researchers are studying the effects of climate change, but most often they are not integrated into agriculture. The paper “Integrating Agriculture and Ecosystems to Find Suitable Adaptations to Climate Change” describes why ecosystem and agricultural adaptation must be taken from an integrated analytical perspective [

59]. In some countries, climate change can represent real opportunities, as presented in the study “Climate change transformations in Nordic agriculture?”. By conducting research to identify adaptation measures, interviews were conducted with farmers in the most fertile areas of Sweden and Finland, identifying the extent to which their farming systems are being transformed. The results indicate that changes are still occurring, most of which are progressive. Farmers find agricultural policies and regulations more difficult than regulations to adapt to climate change [

61].

Lately, research is also focusing on impact-based solutions according to farmers’ gender. Thus, measures on climate change adaptation can be improved if they are linked to the type of climate risks to which, for example, women in agriculture are exposed. The study “Women in agriculture and climate risks: hotspots for development” highlights barriers for women (farmers) when it comes to access to labor, credit or the fact that wages in agriculture are lower for women than for men. Given these shortcomings, climate change measures that women can undertake are more difficult to implement [

61].

Implementing climate change mitigation measures is costly to achieve the targets set. Studies indicate that funding in developing countries for this segment is still not sufficient to achieve tangible results. However, most of the implemented European policies have helped farmers move towards sustainable agriculture [

62]. For instance, monetary policy uncertainty has negative short- and long-term effects on renewable energy consumption, a result that demonstrates the need for vital changes in both renewable and non-renewable energy policies to accommodate monetary policy uncertainties [

63].

Recent research has shown that a positive change in education contributes to an increase in green energy consumption in countries such as Brazil, Russia, India or China, but all of these involve considerable costs [

64].

According to some authors, climate change and agriculture can be seen as two key elements contributing to population migration. Given that the effects of climate change will cause significant economic damage, migration may be a specific form of population response. However, policy actions related to sustainable agriculture and rural development can contribute to the above-mentioned approaches and create opportunities for migration [

65].

2. Materials and Methods

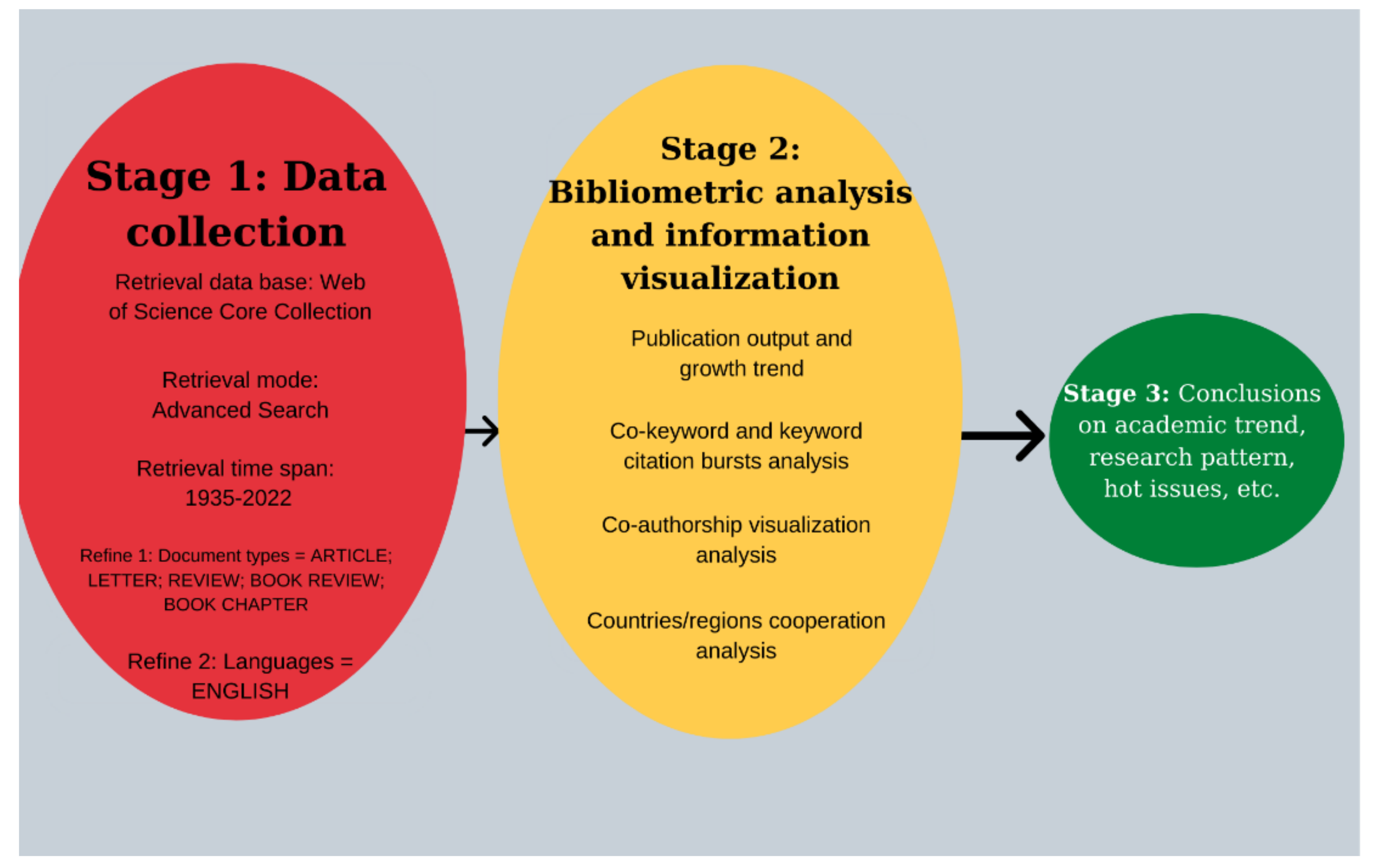

In the first part of the study, a bibliometric analysis of the state of research on climatic effects in agriculture was carried out to highlight the interest shown by researchers in this field, as limiting the effects of climate change cannot be done without each other [

66].

VOSviewer software was used for the bibliometric analysis and the data collected came from the Web of Science database, for which the topic agriculture and climate change was searched. The three steps for making a map are shown in the

Figure 1 below [

65].

Taking into account the fact that agriculture plays a very important economic role, due to the share of agricultural products in the total imports made by Romania, especially in plant production, a quantitative survey was conducted, using a questionnaire as an instrument, among Romanian farmers, with a total of 407 respondents. A questionnaire consisting of a set of 18 open questions with several answer options was sent to them electronically.

The second part of this study covers the sampling method used, convenience sampling using the snowball method [

67,

68]. This method is usually used for samples that are more difficult to identify and specific to qualitative research. Thus, it starts with a low number of participants, which increases as the questionnaire is promoted [

69,

70]. The questionnaire was administered in October–November 2021.

The purpose of the questionnaire was to identify whether Romanian farmers are aware of the effects caused by climate change and know what measures should be taken to combat them. Furthermore, through the set of questions, the level of awareness and the level of preparedness in terms of taking measures to combat the effects of climate change were determined.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). There is a significant link between the level of education and the ability to understand climate change phenomena.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). There is a significant link between the area farmed by farmers and their perceived impacts associated with climate change.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). There is a significant link between the level of studies and the nature of the measures farmers are considering implementing on their farms.

Figure 2 shows the territorial distribution of the farmers surveyed, which generally maintains the territorial distribution of the farms found in Romania, in percentage terms.

The data obtained were analyzed quantitatively using the SPSS e statistical software (SPSS Statistics 20, IBM Software Group, Chicago, IL, USA), for which the frequency, chi-square value, contingency coefficient and Pearsons coefficient were determined [

65,

66].

The independent variables are the type of farm set-up, level of education, main source of on-farm finance and total agricultural area farmed.

The structure of the sample analyzed is as follows:

Type of holding: 76.41%—Limited Liability Company (LLC), 11.55%—Individual Enterprise (I.I.), 5.90%—Family Enterprise (F.E.), 2.70%—Authorized Natural Person (A.N.P.), 1.97%—Joint Stock Company (S.A.), 1.47%—Agricultural Cooperative (C.A.);

Level of education of the farm manager: 55.04%—secondary education, 27.52%—general education, 17.44%—university education;

Main source of financing on the farm: 50.12%—own sources from the marketing of production, 31.45%—subsidies, 18.43%—bank credit;

Total agricultural area explained: 54.79%—50–99.9 ha, 23.59% > 100 ha, 15.72%—30–49.9 ha, 3.93%—10–19.9 ha, 1.97%—<10 ha.

3. Results

The large number of papers on agriculture and climate change illustrates the research concerns on this topic. Thus, 74,465 papers were written between 1935 and 2022 (

Figure 3).

The research areas in which these papers fall are: environmental science (22,418 papers), ecology (9443 papers), atmospheric science methodology (7280 papers), agronomy (7046 papers), water resources (6422 papers), environmental studies (6250 papers) and plant science (5588 papers). Other areas in which papers have been written are: soil science, agriculture, horticulture, geography, biology, urban studies, sociology, pathology and business finance (

Figure 3).

The papers have been written since 1935, reaching their peak in 2012 with 80 papers and decreasing in subsequent years to 14 papers in 2020 (

Figure 3).

With the help of the Web of Science database, a database has been generated in which all publications on the subject of agriculture and climate change have been entered.

The main keywords are weather, climate change, precipitation, yields, food security, climate and agricultural conservation. They are grouped into four clusters.

The first cluster is represented by climate change, risk, economic impact, weather, resources, irrigation, insurance, yields and fluctuations.

The second cluster is represented by agriculture, urbanization, forests, crop production, communities, quality, integrated assessment, area used, urbanization, options, energy, climate, livestock and gender.

The third cluster includes key terms such as variability, temperatures, strategies, models, yields, precipitation, temperatures, sensitivity, potential impact, trends, carbon dioxide, future climate, test, rice production, wheat, climate resilience, water management, uncertainty and variability.

The fourth cluster includes terms such as food security, agroecology, systems, migration, farm system, soil, nitrogen, climate change, impacts of change, area used, conservation agriculture, prospects, challenges, organic farming, intensification, management, emissions, soil carbon, greenhouse gas migration, harvesting system, tillage and soil carbon sequestration (

Figure 4).

The fifth cluster includes terms related to adaptation, vulnerability, perspectives, perceptions, determination, social vulnerability, environment, sustainability, policy, government, adaptation to change, agricultural climate intelligence, trade, smallholders, risk management, context, adaptive capacity and social vulnerability (

Figure 4).

The map above shows the key terms according to the year in which they were used in various scholarly works. Thus, in 2014 and 2015, the main topics for researchers were: precipitation, risks, climate change, soil, carbon dioxide, trends, yields, impacts, crop production, scenarios, food production, wheat and trade (

Figure 5).

In the following years 2016–2017, researchers were concerned with temperature, irrigation, precipitation, vulnerability, farmers, policy, system, farm system, emissions, performance, food, agriculture, biodiversity, changes in area used, future, demand, availability, biodiversity, energy, migration, intensification, management, weather, ecosystem services and sustainability (

Figure 5.).

In 2018 the following topics were addressed: climate smart agriculture, outlook, challenges, perceptions, level, conservation agriculture, urbanization, quality, lessons, economic impact, fluctuations, outputs, innovation, agroforesty, opportunities, sustainable development, communities, genres, framework, no-till, determination, climate change adaptation and perception risk (

Figure 5).

The degree of interrelationship between countries is very important to observe among the countries that are interested in our topic of study. Therefore, the frequency of coauthors and partnerships between institutions is shown through nodes. The colors present in the map show the diversity of research directions addressed, and the thickness of the connections, as well as the distance between them, show the level of cooperation between countries. As a result, the United States, India, Germany and Australia are concerned with agriculture and climate change. It can be seen on the map that there are seven research directions, of which the Netherlands together with Germany, Hungary, Austria address the same research direction, so the European Union is interested in this topic (

Figure 6).

The results of the survey of farmers with crop farms, the second component of the study, are presented below.

The highest proportion of respondents say that the main consideration in selecting input suppliers is the discounts they receive (41.28%). Another important criterion is price, of which 34.4% of respondents list it as their main selection criterion, and 20.39% say that the possibility of payment in kind is a main selection criterion. It is noted that only 3.93% of the respondents have the quality of the products promoted by the merchant as their main selection criterion (

Figure 7).

More than 62% of the respondents say that the technological work on the farm is carried out with their own machinery and equipment, while 26.54% carry out only part of the work with their own machinery and equipment. Only 10.57% of the respondents use third parties to carry out technological work (

Figure 7).

Out of the total 407 respondents, 60.69% own land both in their personal property and on lease, and at the opposite pole are those who work land that is only in their personal property, with a share of only 5.9%. Furthermore, 33.42% of the respondents who worked only leased land (

Figure 7).

Approximately 59% of the respondents believe that climate change causes, to a large extent, fluctuations in the production obtained, while 25.31% are of the opinion that they are caused to a small extent by climate change (

Figure 8).

The main climatic phenomenon faced by 71.5% of respondents is drought, while 13.76% are already facing an aggravated problem, namely the desertification of agricultural land. Only 7.86% of the respondents stated that the most problematic climatic phenomenon is heavy (above average) rainfall (

Figure 9).

A total of 54.14% of respondents had lower yields, which considerably affected their income. Furthermore, 21.05% made additional investments in irrigation systems or planting forestry to combat the effects of climate change, and 16% of respondents had to make additional expenditures, such as plant health treatments (

Figure 10).

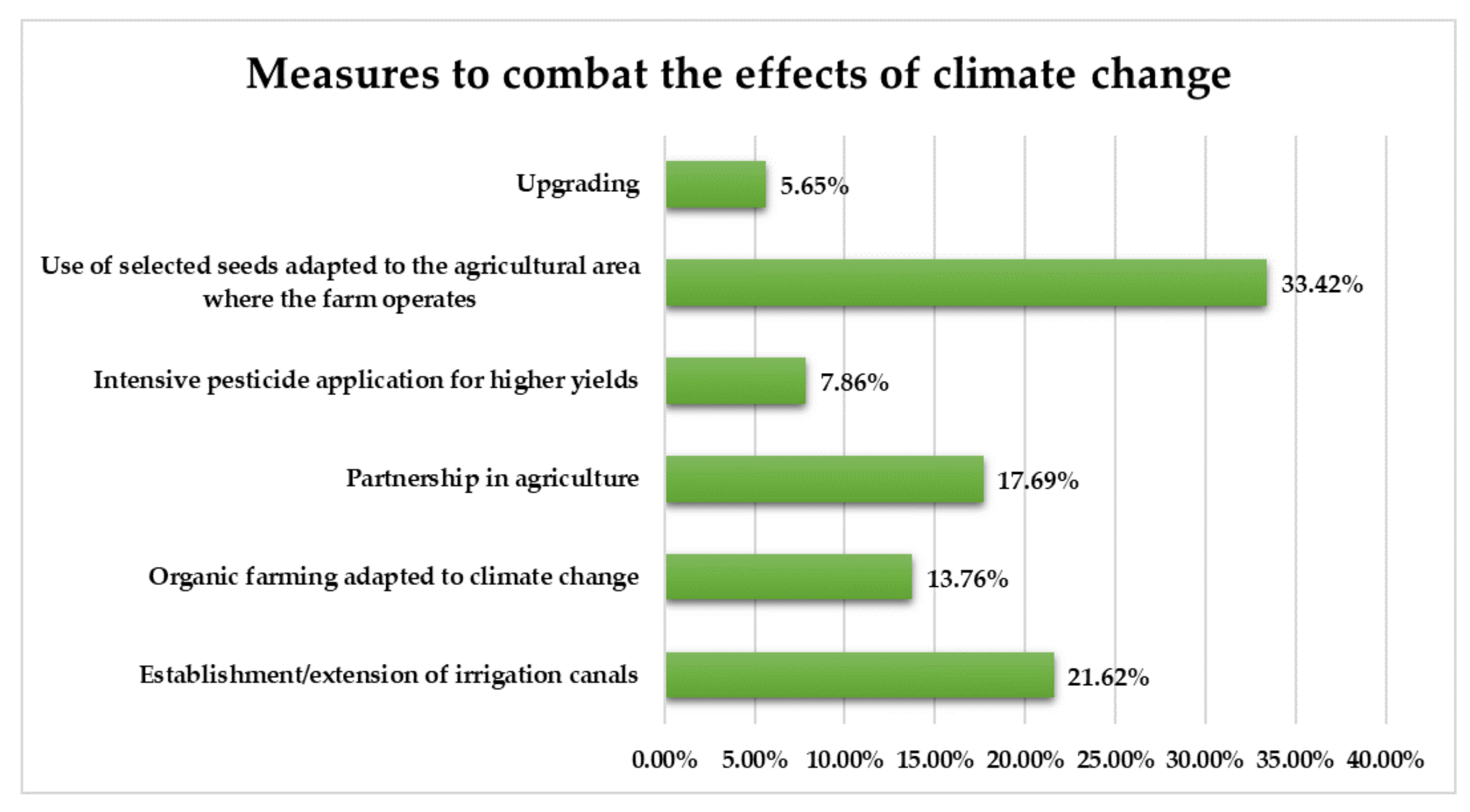

The highest proportion of respondents (33.42%) have made or are considering the use of selected seeds adapted to the agricultural area to combat the effects of climate change, followed by those who want to establish or extend irrigation canals (21.62%). At the same time, 13.76% are considering the transition to organic agriculture adapted to climate change (

Figure 11).

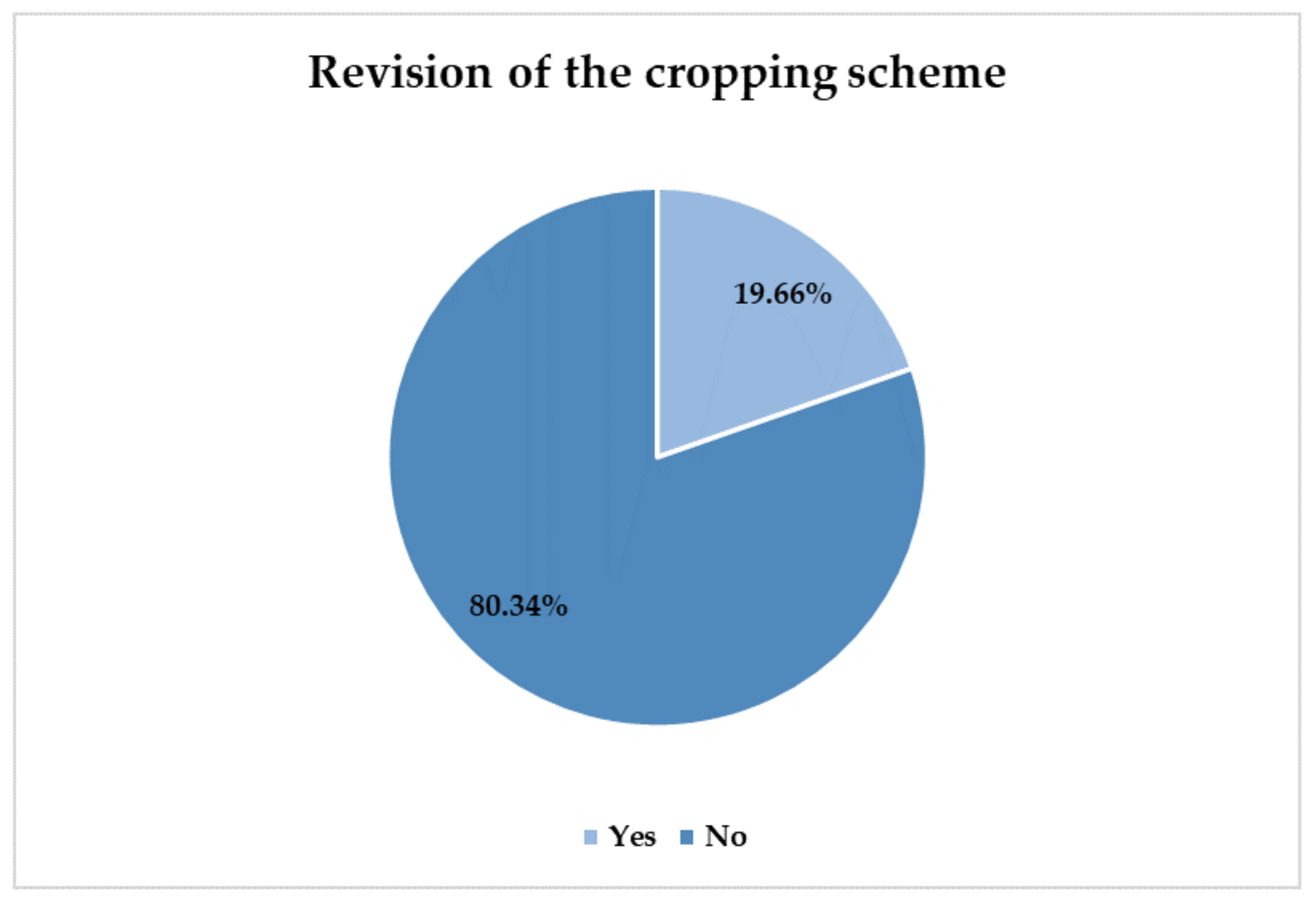

A considerable 80.34% of respondents believe that there is no need to revise the cropping scheme, while only 19.66% think that it should be revised (

Figure 12).

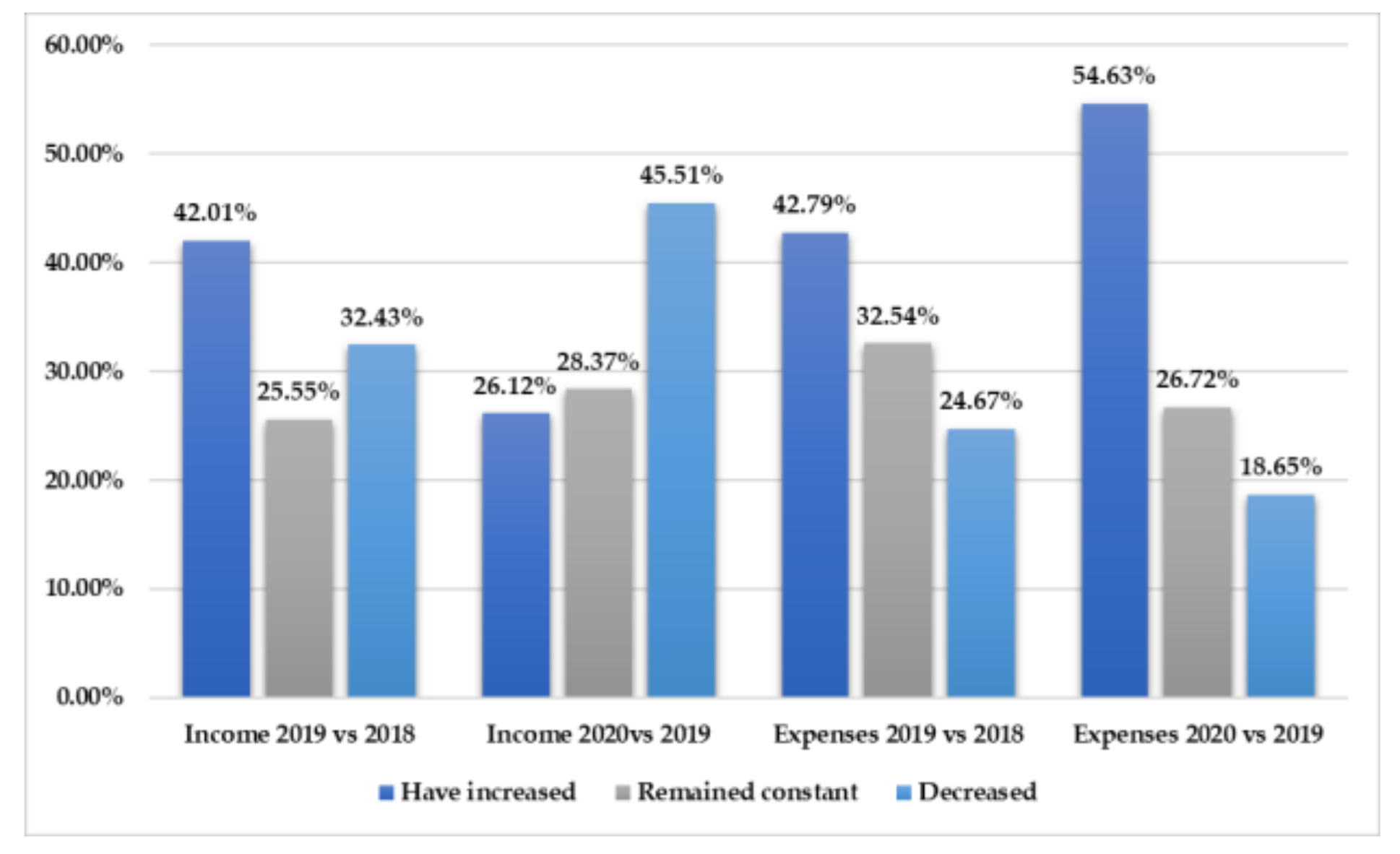

In 2019, compared to 2018, 42% of the respondents said that their income increased, while only 32.43% reported a decrease. At the same time, in 2020, compared to 2019, only 26.12% of respondents reported increases, while more than 45% reported decreases in their income (

Figure 13).

Both in 2019 compared to 2018 and in 2020 compared to 2019, most farmers recorded increases in expenditure (42.79% and 54.63%, respectively), while only 24.67% and 18.65%, respectively, recorded decreases in expenditure in the years analyzed (

Figure 13).

By 2020, 46.19% of respondents stated that they had succeeded in achieving profitability in agriculture, while 36.36% had failed to achieve the expected performance. At the same time 17.44% of them stated that the profit achieved was zero (

Figure 14).

In the future, 61.76% plan to increase their agricultural area, either by buying farmland or leasing, while 34.3% want to maintain the existing area at the farm level. Only 3.93% plan to reduce the area farmed (

Figure 15).

After processing the data, a Chi-square value of 61.494 is revealed, indicating a strong association between the variables analyzed, i.e., between limited liability companies and their opinion on climate change (

Table 1).

The negative value of R (−0.351) indicates the inverse proportionality between the two variables and also the link between their mode of incorporation and their opinion on fluctuations in production (

Table 1).

There is a very strong relationship between limited liability companies and the opinion of respondents who identified lower yields as an effect of climate change, resulting in a chi-square value of 137.363. There is also an association between the mode of incorporation and their opinion on the effects felt/caused by climate change on the agricultural activity carried out, with an R value of 0.393 (

Table 2).

It is important to note that there is a strong correlation between respondents with high school education and their opinion on climate change that affects agricultural production fluctuations to a large extent, with a Chi-square value of 97.352. At the same time, the relationship between the two variables, i.e., the level of education and their opinion on fluctuations in production caused by the effects of climate change, is very strong (R = 0.603) (

Table 3).

After processing the data, a Chi-square value of 97.676 is revealed, indicating a strong association between the variables analyzed, i.e., between respondents with secondary education and their opinion on the use of selected seeds adapted to the agricultural area where the farm operates (

Table 4). The value of R (0.466) indicates a moderate relationship between the level of education and the opinion of the respondents about the measures they want to take on the farm (

Table 4).

The connection is strong between farmers who finance their activity from their own sources and their opinion on climate change that affects, to a large extent, the fluctuations of agricultural production, with a Chi-square value of 47.172. Furthermore, for sources of financing and respondents’ opinion on fluctuations in production caused by climate change effects, there is a moderate association, with an R-value of 0.488 (

Table 5).

After processing the data, the Chi-square value is 47.172, indicating a strong association between the variables analyzed, i.e., between having one’s own sources of funding and attributing lower yields due to the effects of climate change (

Table 6).

The negative value of R (−0.416) indicates the inverse proportionality between the two variables and also the link between sources of financing and opinion on the effects of climate change on agricultural activity (

Table 6).

There is a very strong relationship between farmers farming an area between 50 and 99.9 ha and lower yields due to the effects of climate change, with a Chi-square value of 145.318. There is also a moderate association between area farmed and opinion of the effects felt/caused by climate change on the agricultural activity carried out, with an R value of 0.413 (

Table 7).

There is a very strong relationship between farmers who farm an area between 50 and 99.9 ha and those who plan to use selected seeds adapted to the agricultural area in which they operate, resulting in a Chi-square value of 173.82. There is also an association between area farmed and opinion on the measures they wish to undertake on the farm, with an R value of −0.365 (

Table 8).

According to the research, hypotheses H1, H2 and H3 are true, and there are significant links between the variables analyzed.

4. Discussion

We can say that the topic “agriculture and climate change” is a very important topic, which has been addressed since 1935, being associated with terms such as food security, adaptation, economics, management, temperatures, production, diversity, emissions, precipitation and irrigation. The research directions studied worldwide are diverse and are also addressed by countries in the European Union, such as Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, Poland, Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands.

However, this issue has been more difficult to understand even for the main supporters of agriculture, farmers, but lately, all these actors are working together to limit the effects of climate change.

The results of the survey show a significant share of farmers work land they have leased or work it in a mixed format (own and leased). The traces of the communist regime still persist in the mentality of rural dwellers who, even if they can no longer work the land (high degree of ageing of the rural population), prefer to lease it to a farmer. This can create instability at the farm level, as the area owned by farmers can vary significantly [

2].

Although events may occur that put the cultivated area at risk (varying), farmers prefer technological work to be done with their own machinery, as this is not based on a calculation of the efficiency of purchasing/maintaining their own machinery versus renting agricultural machinery and equipment (management training and accounting notions). This facility could be obtained by joining an associative form, which is still developing timidly in Romania [

7,

15] compared to other countries of the European Union, where agricultural activities carried out in common are widespread [

31,

34,

37].

The discounts received for the purchase of agricultural inputs and implicitly their price is a main argument for Romanian farmers in choosing suppliers, being placed above the “quality” criterion. Obviously, the living standards of consumers force the production of food at the lowest possible cost [

34], but which also forces competition. These criteria could also have been more easily met by joining an association.

While until recently extreme weather events were blamed on traditional customs, with increasing levels of training and education and policies promoted by the European Union, farmers are becoming aware of the effects of climate change. They also associate identified climatic phenomena, such as drought and land desertification, with climate change impacts. At the same time, these effects have caused them additional costs that they have been willing to incur [

12,

18].

It should be noted that there is interest in new scientific developments, and a large proportion of farmers are considering the use of selected seeds, adapted to the agricultural area from which they come, as a measure to combat the effects of climate change [

8].

The demand on the market and the relatively easy marketability of the plant production obtained, together with the experience gained in growing only certain types of crops, mean that there is a proportion who believe that there is no need to revise their cropping pattern. A large proportion of Romanian farmers market their crop production immediately after harvest for storage reasons [

12].

Climatic effects are putting a strain on the incomes of farmers, whose incomes are becoming lower and lower, and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in neighboring Ukraine are forcing them to adapt to these changes, with the majority of respondents wanting to increase the cultivated area [

14], which will contribute to the consolidation of agricultural land and the elimination of non-performing farms (subsistence and semi-subsistence).