Achieving Transformative Change in Food Consumption in Austria: A Survey on Opportunities and Obstacles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Sampling Design

2.3. Scope and Questions of the Survey

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Participants across Groups

3.1.1. General Results

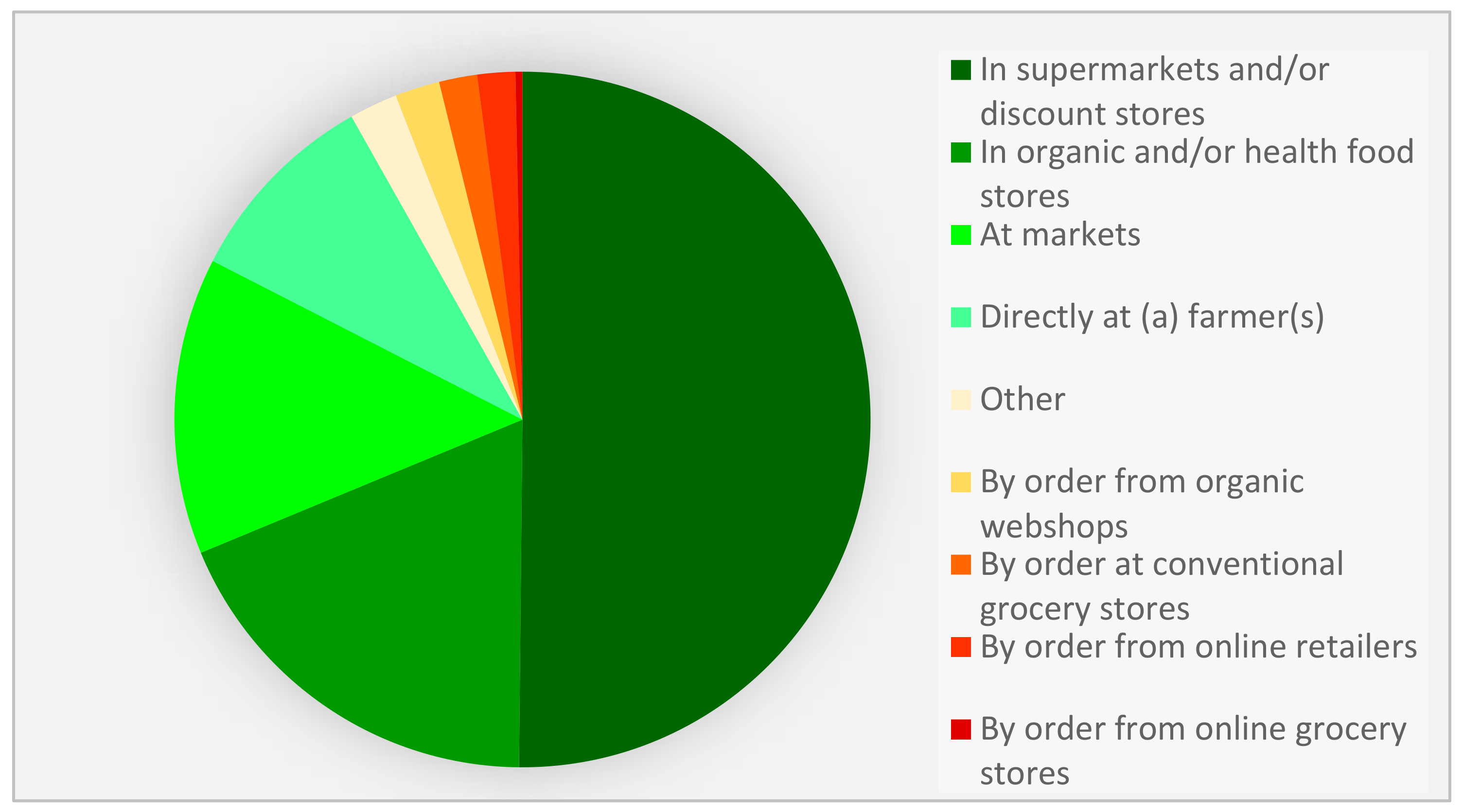

3.1.2. Results for the Total Sample

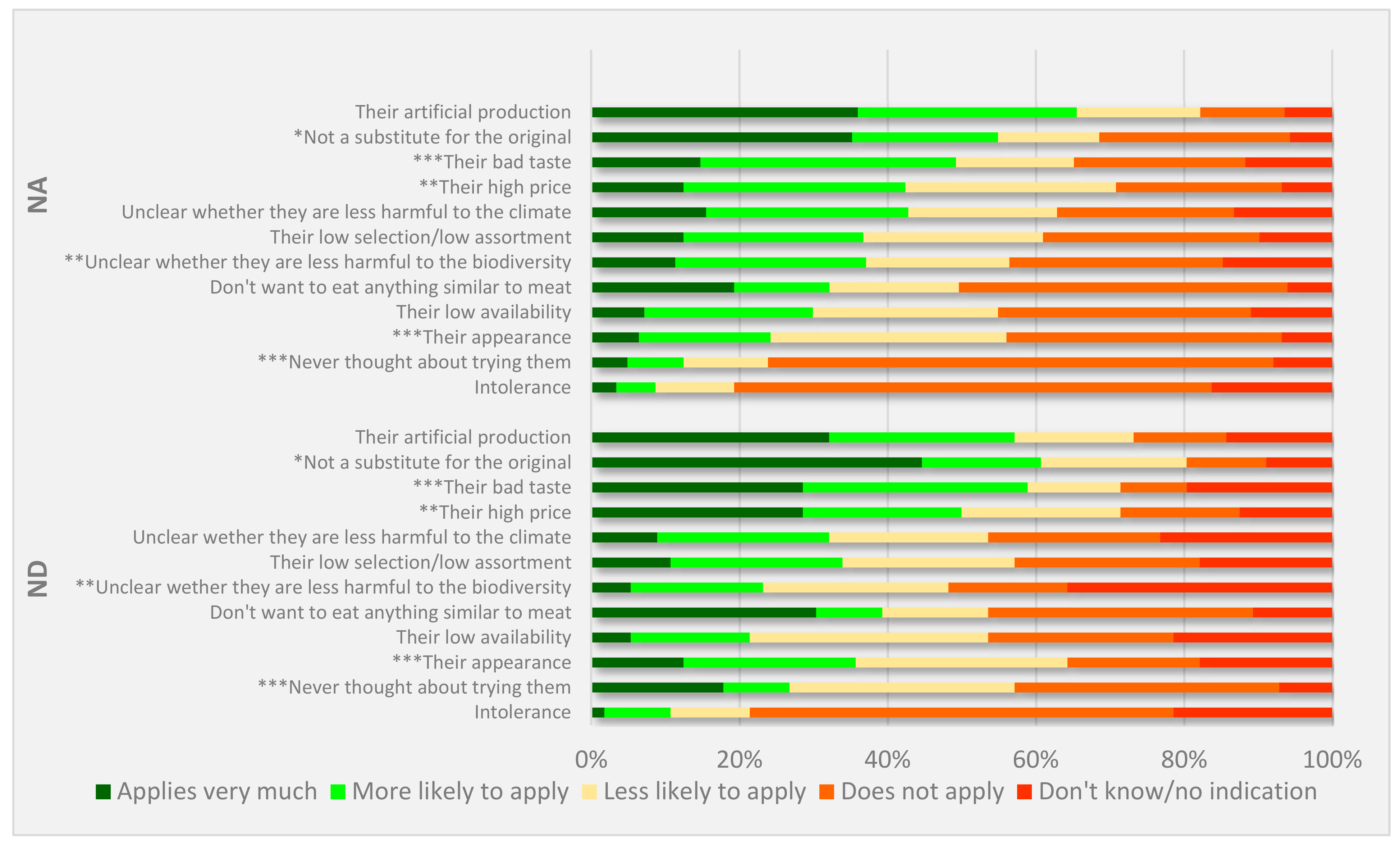

3.2. Comparison among Groups with Different Affinity to Nature Conservation

4. Discussion

4.1. Food Consumption Patterns in Austria

4.2. Obstacles to Transformative Change in Food Consumption

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Barnosky, A.D.; García, A.; Pringle, R.M.; Palmer, T.M. Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Guèze, M.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; et al. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N.; Alexander, S. Agriculture and biodiversity: A review. Biodiversity 2017, 18, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Fuller, R.A.; Brooks, T.M.; Watson, J.E. Biodiversity: The ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature 2016, 536, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lairon, D. Biodiversity and sustainable nutrition with a food-based approach. In Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity; Burlingame, B., Dernini, S., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ferranti, P.; Berry, E.; Jock, A. Encyclopedia of Food Security and Sustainability: General and Global Situation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilting, H.C.; Schipper, A.M.; Bakkenes, M.; Meijer, J.R.; Huijbregts, M.A. Quantifying biodiversity losses due to human consumption: A global-scale footprint analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3298–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.M.; Schmidt, U.J. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Schutter, L.; Bruckner, M.; Giljum, S. Achtung: Heiß und Fettig—Klima & Ernährung in Österreich—Auswirkungen der Österreichischen Ernährung auf das Klima; WWF Österreich: Vienna, Austria, 2015; pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bethlehem, J.; Biffignandi, S. Handbook of Web Surveys; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Höbart, R.; Schindler, S.; Essl, F. Perceptions of alien plants and animals and acceptance of control methods among different societal groups. NeoBiota 2020, 58, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearson, K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philos. Mag. J. Ser. 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA-OTS Österreich. Meinungsraum.at-Studie: Veganer Würden Bis zu 50 Prozent Mehr für Lebensmittel Bezahlen. 2018. Available online: https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20180419_OTS0105/meinungsraumat-studie-veganer-wuerden-bis-zu-50-prozent-mehr-fuer-lebensmittel-bezahlen-anhang (accessed on 24 July 2021).

- AMA. 25 Jahre Einkaufen: Megatrends Convenience und Bio. 2019. Available online: https://amainfo.at/article/25-jahre-einkaufen-megatrends-convenience-und-bio (accessed on 24 July 2021).

- Iseli, D. Psychologische Einflussfaktoren auf die Entscheidung für OderGegen Eine Vegane Ernährung. Bachelor’s Thesis, Fachhochschule Nordwestschweiz, Olten, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, E.A.; Evang, E.; Metz, M.; Schneider, K. Einflussfaktoren auf den Fleischkonsum; Poster at 52; Wissenschaftlicher Kongress der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ernährung: Halle, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Albersmeier, F.; Mörlein, D.; Spiller, A. Zur Wahrnehmung der Qualität von Schweinefleisch beim Kunden, Diskussionsbeitrag; No. 0912; Department für Agrarökonomie und Rurale Entwicklung (DARE), Georg-August-Universität Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weinrich, R. Labelling policies for food. Ph.D. Thesis, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karstens, B.; Belz, F.M. Information asymmetries, labels and trust in the German food market: A critical analysis based on the economics of information. Int. J. Advert. 2006, 25, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S. Entwicklung des Konsums von ökologisch erzeugten Lebensmitteln in Bayern-dargestellt am Vergleich von Konsumentenbefragungen aus den Jahren 2004, 1998 und 1992. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, München, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers GmbH Wirtschaftsprüfungsgesellschaft. Bio im Aufwind. Konsumentenbefragung zu Bio-Lebensmitteln und Deren Kennzeichnung, Frankfurt/Main, Germany. 2021. Available online: https://www.pwc.de/de/handel-und-konsumguter/pwc-bio-im-aufwind.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Perrini, F.; Castaldo, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility associations on trust in organic products marketed by mainstream retailers: A study of Italian consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.; Fujiyoshi, L.; McGreevy, S.R.; Tayasu, I. Trust me? Consumer trust in expert information on food product labels. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 137, 111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umweltbundesamt. Fleisch der Zukunft: Trendbericht zur Abschätzung der Umweltwirkungen von Pflanzlichen Fleischersatzprodukten, Essbaren Insekten und In-Vitro-Fleisch. Umweltbundesamt, Dessau, Germany. 2019. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/2020-06-25_trendanalyse_fleisch-der-zukunft_web_bf.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Köster, J. Die Wahrnehmung Deutscher Verbraucher von In-Vitro-Fleisch als Alternative zur Konventionellen Fleischherstellung—Eine Empirische Analyse der Chancen und Herausforderungen. Bachelor’s Thesis, Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chemnitz, C.; Wenz, K. Fleischatlas; Heinrich Böll Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.boell.de/de/fleischatlas (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Kiy, M.; Terlau, W. Konsumentenbefragungen zum Thema “Fair Trade” und “Bio” an Hochschulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen. In Der Verantwortungsvolle Verbraucher: Aspekte des Ethischen, Nachhaltigen und Politischen Konsums; Bala, C., Schuldzinski, W., Eds.; Verbraucherzentrale Nordrhein-Westfalen e.V.: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, T. Der Biomilchmarkt aus Sicht der Konsumenten; Herbstmilchtagung der Bio Suisse, Olten, Schweiz; Forschungsinstitut für Biologischen Landbau: Frick, Switzerland, 26 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Koerber, K.V.; Kretschmer, J. Die Preise von Bio-Lebensmitteln als Hürde bei der Agrar- und Konsumwende. Ernährung Im Fokus 2001, 1, 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Lehner, N.; Fiala, V.; Freyer, B. Einstellungen, Einflussfaktoren und Verhaltensmuster zu Bio-Konsum—Eine Fallstudie über Mehrpersonenhaushalte mit geringer Kaufkraft. In Innovatives Denken für Eine Nachhaltige Land- und Ernährungswirtschaft, Contributions to the 15th Proceedings of the Science Conference on Organic Farming, Kassel, Germany, 5–8 March 2019; Verlag Dr. Köster: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, K.; Basil, M.; Maibach, E.; Goldberg, J.; Snyder, D.A.N. Why Americans eat what they do: Taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1998, 98, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, B.; Omann, I.; Pack, A. Socio-economic drivers of (non-) sustainable food consumption. An analysis for Austria. In Proceedings of the Launch Conference of the Sustainable Consumption Research Exchange, Wuppertal, Germany, 23–25 November 2006; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Buder, F.; Hamm, U. Determinanten der Nachfrage ökologischer Lebensmittel. In Proceedings of the Scientific Conference on Organic Farming, Gießen, Germany, 15–18 March 2011; Verlag Dr. Köster: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Visschers, V.; Tobler, C.; Cousin, M.E.; Brunner, T.; Orlow, P.; Siegrist, M. Konsumverhalten und Förderung des Umweltverträglichen Konsums; Bericht im Auftrag des Bundesamtes für Umwelt BAFU: Ittigen, Switzerland, 2009; 121p. [Google Scholar]

- Haubach, C.; Moser, A.; Schmidt, M.; Wehner, C. Die Lücke schließen—Konsumenten zwischen ökologischer Einstellung und nicht-ökologischem Verhalten. Wirtschaftspsychologie 2013, 15, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pack, A. The Environmental Sustainability of Household Food Consumption in Austria: A Socio-Economic Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Universität Graz, Graz, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schäufele, I.; Hamm, U. Bestimmungsgründe für den Kauf von Öko-Lebensmitteln: Liegen produktgruppenspezifische Unterschiede vor? In Innovatives Denken für Eine Nachhaltige Land-Und Ernährungswirtschaft, Contributions to the 15th Proceedings of the Science Conference Organic Farming, Kassel, Germany, 5–8 March 2019; Verlag Dr. Köster: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz, H.; Blattert, S.; Rebholz, T.; Stolze, M. Biobarometer Schweiz: Wovon die Kaufentscheidung für Biolebensmittel abhängt. Agrar. Schweiz 2017, 8, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer attitudes towards environmental concerns of meat consumption: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farjam, M.; Nikolaychuk, O.; Bravo, G. Experimental evidence of an environmental attitude-behavior gap in high-cost situations. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 166, 106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, I.; Puelles, M. The connection between environmental attitude–behavior gap and other individual inconsistencies: A call for strengthening self-control. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2017, 26, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, G.; Schramm, M.; Spiller, A. The reliability of certification: Quality labels as a consumer policy tool. J. Consum. Pol. 2005, 28, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzburger Nachrichten. Penny will Anfang 2021 das Bio-Sortiment Verdoppeln. 27 October 2020. Available online: https://www.sn.at/wirtschaft/oesterreich/penny-will-anfang-2021-das-bio-sortiment-verdoppeln-94763011 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- RollAMA Marketing GesmbH. Marktentwicklung Bio 1. Quartal 2021. Haushaltspanel 2.800 Österreichischer Haushalte, Vienna, Austria. 2020. Available online: https://amainfo.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Charts_PA_RollAMA2021.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haider, V.; Essl, F.; Zulka, K.P.; Schindler, S. Achieving Transformative Change in Food Consumption in Austria: A Survey on Opportunities and Obstacles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148685

Haider V, Essl F, Zulka KP, Schindler S. Achieving Transformative Change in Food Consumption in Austria: A Survey on Opportunities and Obstacles. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148685

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaider, Verena, Franz Essl, Klaus Peter Zulka, and Stefan Schindler. 2022. "Achieving Transformative Change in Food Consumption in Austria: A Survey on Opportunities and Obstacles" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148685

APA StyleHaider, V., Essl, F., Zulka, K. P., & Schindler, S. (2022). Achieving Transformative Change in Food Consumption in Austria: A Survey on Opportunities and Obstacles. Sustainability, 14(14), 8685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148685