Is the Timber Construction Sector Prepared for E-Commerce via Instagram®? A Perspective from Brazil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Timber Construction and the Demand about its Electronic Market

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Delimitation of Virtual Platforms to Collect Data

2.2. Company Prospection through Corporate Profile Selection on Instagram®

2.3. Survey, Query Delineation and Justification for Sectoral Evaluation and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Proposal of Classification for Corporate Profiles on Instagram®

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Company Prospection, Sectoral Sampling, and Statistical Analysis

3.2. Sectoral Evaluation Using Aspects and Contents of Corporate Profiles on Instagram®

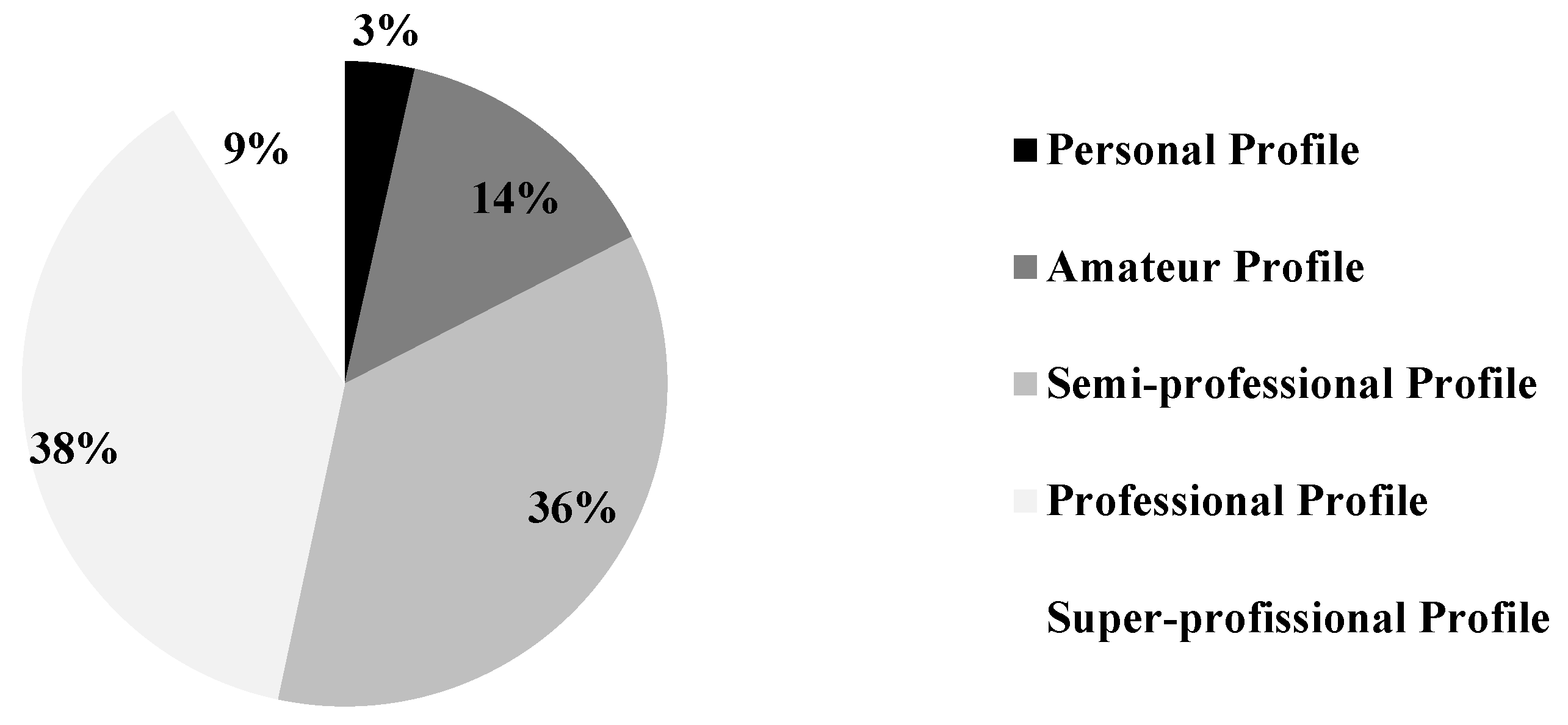

3.3. Classification to Evaluate the Current Status of Corporate Profiles on Instagram®

- The organized and complete statement of the data contained in the biography so that potential clients can truly know the company’s name as well as corporate goals and merchandise, detailed locations and forms of contact for direct service;

- The disclosure of more detailed building projects so that clients visualize and analyze the available construction techniques and the lists of necessary materials and quantities per technique, included and not included services, possible technical limitations, main deadlines, and client obligations;

- The specification of prices for finished houses and cost estimates for custom projects to satisfy the expectations and curiosities of new clients and, with that, create and support the electronic markets to be developed by corporate profiles on Instagram®;

- For amateur profiles, there are suggestions to adapt publications by inserting photos of the working sites and buildings in superior quality, inserting images of complete projects, correcting textual contents, detailing corporate information, and eliminating errors and inadequacies.

- For personal profiles, new corporate profiles may be created with regular content and satisfactory quality, above all, without inadequacies and with content specifically about the company’s goals and activities;

- There is the possibility to establish the regular management of their profiles by social-media and marketing professionals as managers and analysts;

- The performance of additional studies aligned with current and potential clients to identify their aspirations about the virtual markets of timber housing and their expectations about profiles through the scope of contents such as images, photographs, technical information and other clarifications.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Shatanawi, H.; Osman, A.; Ab Halim, M. The importance of market research in implementing marketing programs. Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2014, 3, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, L.; Williams, F. Remote rural home based businesses and digital inequalities: Understanding needs and expectations in a digitally underserved community. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednall, D.; Valos, M. Marketing research performance and strategy. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2005, 54, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teichmann, M.; Kuta, D.; Endel, S.; Szeligova, N. Modeling and Optimization of the Drinking Water Supply Network—A System Case Study from the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuda, F.; Dlask, P.; Teichmann, M.; Beran, V. Time—Cost Schedules and Project–Threats Indication. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutá, D.; Wernerová, E.; Teichmann, M. Aspects of Housing Assessment and their Influence on the Form of Housing in Apartment Houses in the Czech Republic. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2020, 47, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedar, M. Virtual marketing in virtual enterprises in current globalised market. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerova, E.; Kuda, F.; Faltejsek, M. BIM as an effective tool of project and facility management. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConf. SGEM 2018, 18, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerová, E.; Teichmann, M. Facility management in the operation of water supply networks. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConf. SGEM 2017, 17, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M. Virtual market for agricultural commodities. IMI Konnect 2018, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Danilova, N.; Kuznetsova, Y. Market analysis instruments in the development of the startup marketing strategy. Evropský Časopis Ekon. Manag. 2020, 6, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallstedt, S.; Isaksson, O.; Rönnbäck, A. The need for new product development capabilities from digitalization, sustainability, and servitization trends. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzarasa, G.; Burgert, I. Designing functional wood materials for novel engineering applications. Holzforschung 2021, 76, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antošová, N.; Šťastný, P.; Petro, M.; Krištofič, Š. Application of additional insulation to ETICS on surfaces with biocorrosion. Acta Polytech. 2021, 61, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ďubek, M.; Makýš, P.; Petro, M.; Ellingerová, H.; Antošová, N. The Development of Controlled Orientation of Fibres in SFRC. Materials 2021, 14, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Araujo, V.; Biazzon, J.; Morales, E.; Cortez-Barbosa, J.; Gava, M.; Garcia, J. Materiais lignocelulósicos em uso pelo setor produtivo de casas de madeira no Brasil. Rev. Inst. Florest. 2020, 32, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, V.; Vasconcelos, J.; Gava, M.; Christoforo, A.; Lahr, F.; Garcia, J. What does Brazil know about the origin and uses of tree species employed in the housing sector? Perspectives on available species, origin and current challenges. Int. For. Rev. 2021, 23, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, M. Market potentials for timber-concrete composites in Germany’s building construction sector. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2017, 75, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, F.; Silveira, M.; Garlet, A. Natural durability and improved resistance of 20 Amazonian wood species after 30 years in ground contact. Holzforschung 2021, 75, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolenski, A.; Peixoto, R.; Aquino, V.; Christoforo, A.; Lahr, F.; Panzera, T. Evaluation of mechanical strengths of tropical hardwoods: Proposal of probabilistic models. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2020, 78, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolin, L.; Moritani, F.; Rodegheri, P.; Lahr, F. Properties relationship evaluation and plasticity analytical model approach for Brazilian tropical species. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2021, 79, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, C.; Schmitt, U.; Niemz, P. A brief overview on the development of wood research. Holzforschung 2022, 76, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, V.; Vasconcelos, J.; Biazzon, J.; Morales, E.; Cortez, J.; Gava, M.; Garcia, J. Production and market of timber housing in Brazil. Pro. Ligno. 2020, 16, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- De Araujo, V.; Vasconcelos, J.; Morales, E.; Lahr, F.; Christoforo, A. Characterization of business poles of timber houses in Brazil. Mercator 2021, 20, e20026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruch, M.; Walcher, D. Timber for future? Attitudes towards timber construction by young millennials in Austria—Marketing implications from a representative study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, R.; Lilja, A.; Vihemäki, H.; Toppinen, A. Future export markets of industrial wood construction—A qualitative backcasting study. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 128, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jussila, J.; Nagy, E.; Lähtinen, K.; Hurmekoski, E.; Häyrinen, L.; Mark-Herbert, C.; Roos, A.; Toivonen, R.; Toppinen, A. Wooden multi-storey construction market development—Systematic literature review within a global scope with insights on the Nordic region. Silva Fenn. 2022, 56, 10609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, L.; Pedro, J. Caracterização da Oferta de Casas de Madeira em Portugal: Inquérito às Empresas de Projecto, Fabrico, Construção e Comercialização; Relatório 118/2011-NAU; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011; pp. 1–173. [Google Scholar]

- Egan Consulting. Annual Survey of UK Structural Timber Markets: Market Report 2016; Structural Timber Association: Alloa, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shigue, E. Difusão da Construção em Madeira no Brasil: Agentes, Ações e Produtos. Ph.D. Thesis, University of São Paulo, São Carlos, Brazil, 2018; pp. 1–237. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, T.; Natterer, J.; Schweitzer, R.; Volz, M.; Winter, W. Timber Construction Manual; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–375. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, H.; Krötsch, S.; Winter, S. Manual of Multistorey Timber Construction; Detail Business Information: Munich, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- De Araujo, V.; Cortez-Barbosa, J.; Gava, M.; Garcia, J.; Souza, A.; Savi, A.; Morales, E.; Molina, J.; Vasconcelos, J.; Christoforo, A.; et al. Classification of wooden housing building systems. BioResources 2016, 11, 7889–7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Araujo, V.; Gutiérrez-Aguilar, C.; Cortez-Barbosa, J.; Gava, M.; Garcia, J. Disponibilidad de las técnicas constructivas de habitación en madera, en Brasil. Rev. Arquit. 2019, 21, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Araujo, V. Timber construction as a multiple valuable sustainable alternative: Main characteristics, challenge remarks and affirmative actions. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, A. Wood Market Trends in Europe. SP-49. Trend 3; FPInnovations: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2008; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, N. Timber Utilisation Statistics 2015; Timbertrends: Alicante, Spain, 2015; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- MBIE—Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Building and Construction Sector Trends Annual Report 2021; MBIE: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021; pp. 1–39.

- Hurmekoski, E.; Jonsson, R.; Nord, T. Context, drivers, and future potential for wood-frame multi-story construction in Europe. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 99, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppelhuber, J.; Bauer, B.; Wall, J.; Heck, D. Industrialized timber building systems for an increased market share: A holistic approach targeting construction management and building economics. Procedia Eng. 2017, 171, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. Evaluating the Feasibility of Mass Timber as a Mainstream Building Material in the US Construction Market: Industry Perception, Cost Competitiveness, and Environmental Performance Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Civil and Construction Engineering, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2021; pp. 1–187. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Ahmad, N.; Waqas, M.; Abrar, M. COVID-19 pandemic and construction industry: Impacts, emerging construction safety practices, and proposed crisis management. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqui, P.; Bica, I.; Marra, V.; Ercole, A.; van der Schaar, M. Ethnic and regional variations in hospital mortality from COVID-19 in Brazil: A cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, A.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z.; Glaeser, E.; Luca, M.; Stanton, M. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17656–17666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Araujo, V.; Nogueira, C.; Savi, A.; Sorrentino, M.; Morales, E.; Cortez-Barbosa, J.; Gava, M.; Garcia, J. Economic and labor sizes from the Brazilian timber housing production sector. Acta Silv. Lignaria Hung. 2018, 14, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Araujo, V.; Vasconcelos, J.; Morales, E.; Savi, A.; Hindman, D.; O’Brien, M.; Negrão, J.; Christoforo, A.; Lahr, F.; Cortez-Barbosa, J.; et al. Difficulties of timber housing production sector in Brazil. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 15, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, V.; Morales, E.; Cortez-Barbosa, J.; Gava, M.; Garcia, J. Public support for timber housing production in Brazil. Cerne 2019, 25, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raosoft. Raosoft Sample Size Calculator; Raosoft: Seattle, DC, USA, 2004; Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Heräjärvi, H.; Kunttu, J.; Hurmekoski, E.; Hujala, T. Outlook for modified wood use and regulations in circular economy. Holzforschung 2020, 74, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.; Jöhnk, J.; Vogt, F.; Urbach, N. IIoT platforms’ architectural features—A taxonomy and five prevalent archetypes. Electron. Mark. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci, N.; Tanyeri, M. Stakeholder and resource-based antecedents and performance outcomes of green export business strategy: Insights from an emerging economy. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022, 17, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaundiyal, M.; Coughlan, J. Extending alliance management capability in individual alliances in the post-formation stage. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Cai, F.C.; Bodenhausen, G.V. The boomerang effect of zero pricing: When and why a zero price is less effective than a low price for enhancing consumer demand. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förster, M.; Bansemir, B.; Roth, A. Employee perspectives on value realization from data within data-driven business models. Electron. Mark. 2022, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.T.H.; Domingo, N.; Rasheed, E.; Park, K. Strategic collaboration in managing existing buildings in New Zealand’s state schools: School managers’ perspectives. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2022, 40, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukti, I.Y.; Henseler, J.; Aldea, A.; Govindaraju, R.; Iacob, M.E. Rural smartness: Its determinants and impacts on rural economic welfare. Electron. Mark. 2022, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Lozano, C.P.; Collazzo, P. Corporate social responsibility, green innovation and competitiveness—Causality in manufacturing. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2022, 32, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saabye, H.; Kristensen, T.B.; Wæhrens, B.V. Developing a learning-to-learn capability: Insights on conditions for Industry 4.0 adoption. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, B.; Fuchs, C.; Maira, E.; Puntoni, S.; Schreier, M.; van Osselaer, S.M.J. Sales and self: The noneconomic value of selling the fruits of one’s labor. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.; Castro, G.; Silva, H.; Nunes, J. Pesquisa de Mercado; Editora FGV: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin, J. (Ed.) Impact of internet on market-driven decisions. In Changing Market Relationships in the Internet Age. Chapter 4; Presses Universitaires de Louvain: Lovain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2008; pp. 125–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovska, L. Customer services and their role for industrial small and medium companies. Ekon. Vadyb. 2009, 14, 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kemi, A.O. Impact of social network on society: A case study of Abuja. Am. Sci. Res. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2016, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Isachenko, N.N. The Role of Information and Informational and Communication Technologies in Modern Society. Utopía Prax. Latinoam. 2018, 23, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikoo, A.A.; Thakur, S.S.; Guroo, T.A.; Lone, A.A. Development of society under the modern technology—A review. Sch. Int. J. Bus. Policy Gov. 2018, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuda, M.; Nishi, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Terunuma, T. Construction of a virtual supply chain using enterprise e-catalogues. Procedia CIRP 2020, 93, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.E.K.; Törrönen, P. Business suppliers’ value creation potential: A capability-based analysis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2003, 32, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvanchi, A.; Khafri, A.; Bidakhavidi, N. Virtual construction market. Int. Acad. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 5, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.; Oyedele, L.; Beach, T.; Demian, P. Augmented and virtual reality in construction: Drivers and limitations for industry adoption. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specificity | Considered Term |

|---|---|

| General contents | Timber house, wooden construction, timber housing, green wooden building, sustainable wooden building, prefabricated kit, prefabricated wooden building, prefabricated timber, prefabricated wooden house, dry wooden construction |

| Building techniques | Light-woodframe, log-home, post-and-beam, half-timbered frame, CLT-based building, modular building, clapboard and wainscot, floating wooden house, wooden chalet |

| Question | Justification | Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Query 1: investigate the information described on each profile biography | Analyze the initial communication to clients by means of all objectives and data declared in each profile | Company’s name; direction; service region; website address; production data; electronic contacts (e-mails); phone contacts; products; services. |

| Query 2: investigate the different types of contact with clients described on each profile | Analyze the use and description of different communication channels to establish contact with clients | Website address; mobile number; WhatsApp® contact; wire-line phone number; Facebook® page; Youtube® profile; e-mail; No data. |

| Query 3: investigate the declaration of company direction of each profile | Analyze the declaration of company location and direction for clients | Full direction (street, number, city); State; City; No data. |

| Query 4: investigate the contents of posts (texts, videos and photos) | Analyze the corporate decisions in the posts and respective contents | Inconveniencies (plagiarism, kids, animals, people, etc.); completed buildings; buildings in progress; infrastructures (plants, headquarters, etc.); work teams (building sites, offices, plants, etc.); institutional posts; absence of posts. |

| Query 5: investigate as each profile discloses the timber house projects | Analyze the forms of presentation of timber house designs (developed and in progress) | Floor plans; electronic mockups; rendered mockups; no project. |

| Query 6: investigate the presence of timber house pricing in each profile | Analyze the presentation of pricing (products and services) contained in the profile publications | Prices in different products; specific promotional prices; no price. |

| Query 7: investigate the features of the profile model | Analyze the general presentation of each profile and classify it through available contents | Personal profile; amateur profile; semi-professional profile; professional profile; super-professional profile. |

| Profile Type | Features under Consideration during the Observation |

|---|---|

| Super Professional | Complete contents, detailed corporate information, synthetic texts, framed photos with visual quality, and absence of errors and inadequacies |

| Professional | Satisfactory contents, detailed corporate information, synthetic texts, framed photos with visual quality, and absence of errors and inadequacies |

| Semi Professional | Basic contents, superficial corporate information, generic texts, photos with some visual quality, and presence of few errors and inadequacies |

| Amateur | Scarce contents, superficial corporate information, textual clutters, photos without visual quality, and excessive presence of errors and inadequacies |

| Personal | Absent contents and corporate information, photos without visual quality, excessive presence of errors and inadequacies, and personal publications |

| Population in 2021 | Unitary Volume (Companies) | Sectoral Percentage (%) | Margin of Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Companies prospected | 402 | 100 | – |

| Companies in Instagram® | 315 | 78 | ±2.57 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Araujo, V.; Švajlenka, J.; Vasconcelos, J.; Santos, H.; Serra, S.; Almeida Filho, F.; Paliari, J.; Lahr, F.R.; Christoforo, A. Is the Timber Construction Sector Prepared for E-Commerce via Instagram®? A Perspective from Brazil. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148683

De Araujo V, Švajlenka J, Vasconcelos J, Santos H, Serra S, Almeida Filho F, Paliari J, Lahr FR, Christoforo A. Is the Timber Construction Sector Prepared for E-Commerce via Instagram®? A Perspective from Brazil. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148683

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Araujo, Victor, Jozef Švajlenka, Juliano Vasconcelos, Herisson Santos, Sheyla Serra, Fernando Almeida Filho, José Paliari, Francisco Rocco Lahr, and André Christoforo. 2022. "Is the Timber Construction Sector Prepared for E-Commerce via Instagram®? A Perspective from Brazil" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148683

APA StyleDe Araujo, V., Švajlenka, J., Vasconcelos, J., Santos, H., Serra, S., Almeida Filho, F., Paliari, J., Lahr, F. R., & Christoforo, A. (2022). Is the Timber Construction Sector Prepared for E-Commerce via Instagram®? A Perspective from Brazil. Sustainability, 14(14), 8683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148683