The Need for Global Green Marketing for the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Concept of Green Marketing

2.1. The Concept of Sustainability

2.2. Triple Bottom Line

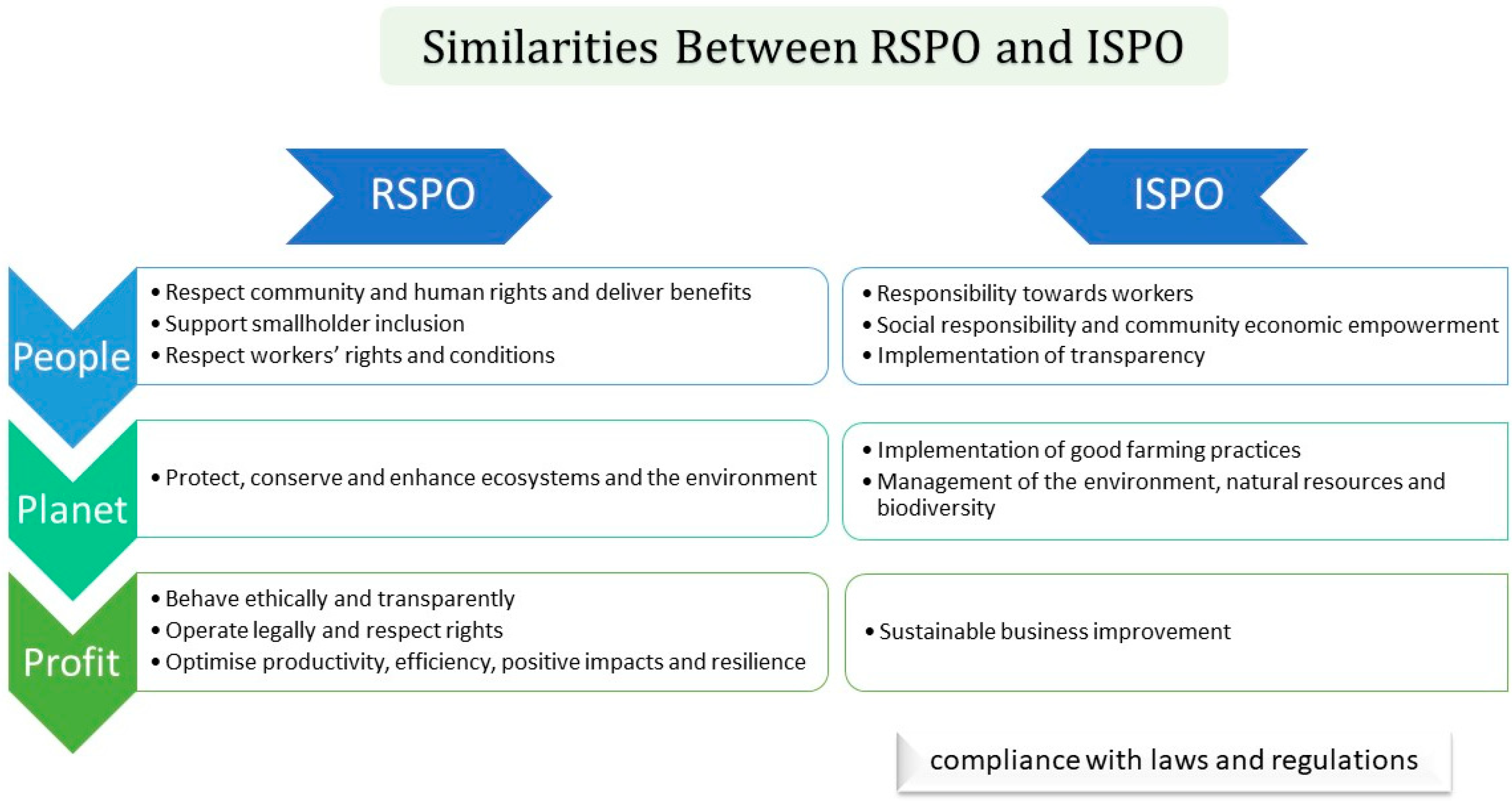

2.3. The Sustainability factor of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) Standard

2.4. Green Marketing

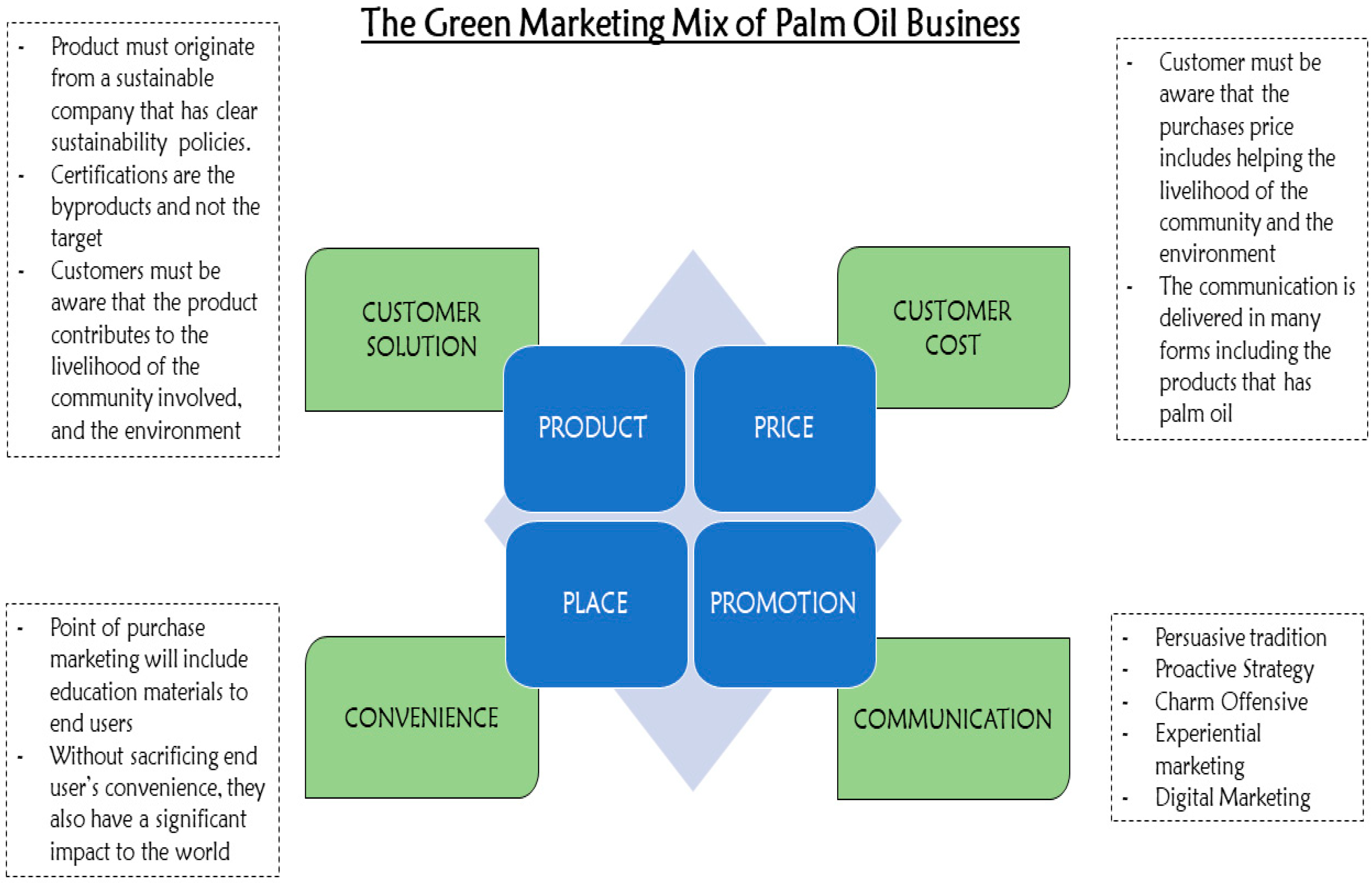

2.5. The Four “Cs“

2.5.1. Customer Solution

2.5.2. Consumer Cost

2.5.3. Convenience

2.5.4. Communication

3. Discussion

3.1. Green Marketing Strategy of Palm Oil

3.2. Competitor or Adverse Contender

3.3. Consumers

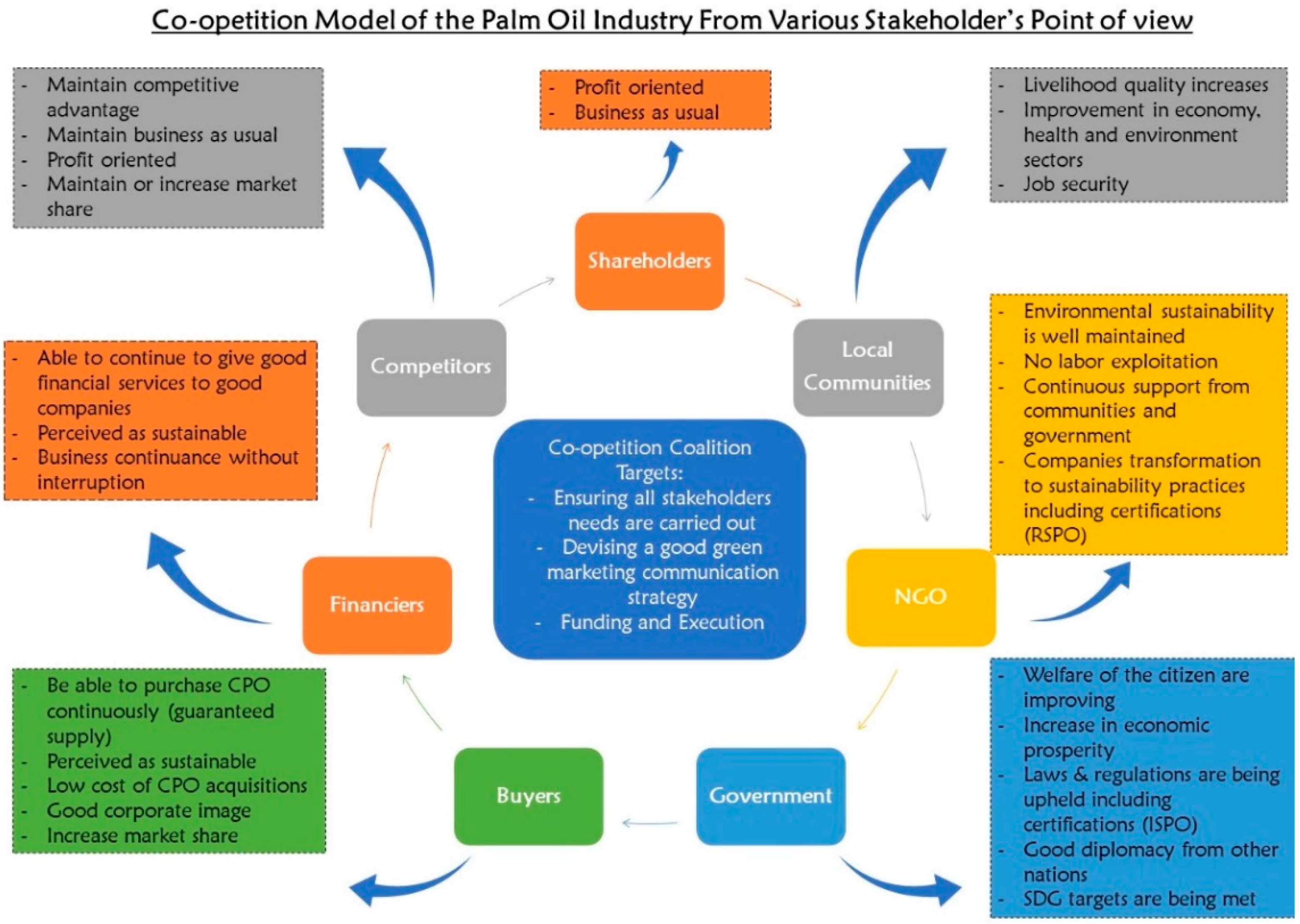

3.4. Collaboration Coopetition Relationship Strategy

Possible Green Marketing Strategy of Palm Oil Companies

- Product–Customer Solution

- 2.

- Price–Consumer Cost

- 3.

- Place–Convenience

- 4.

- Promotion–Communication

- Persuasive tradition

- o

- By challenging certain findings and certain claims from competitors in the case of extremist NGOs, one can question their data and credentials.

- o

- Lobbying key government members to explain the point of view of the coalition, and also to initiate dialogues not just with a certain stakeholder with a specific agenda but with a more comprehensive and holistic coalition.

- Proactive strategy

- o

- By creating advertisements that have a strong emotional element. Stories can be devised from plantation workers, a forgotten village that is transformed due to palm oil, a child that is elevated from poverty, helping and nurturing wildlife animals that live near the plantation, and many other stories that are fit for the mainstream community to observe and react to emotionally.

- o

- Creating a tagline that is easily understood for the palm oil plantation industry in doing good for the environment and sustainability, such as in the case of the coal companies that use the slogan “Cut emissions, not jobs” [72].

- o

- Support local market communities and provide financial assistance to the local economy so that the market will know that the impact of their purchase has a direct positive impact on their livelihood as well.

- Charm offensive

- o

- By using relationship marketing, the coalition can create a story of how, by buying palm oil products, they can exert a very positive impact on the environment and society.

- o

- By showing that in every part of their daily lives, palm oil products have always been there and should be there for the good of the community, not a place with which they have no relationship, but something close or a person they may know.

- o

- Use real people as endorsers and communities to actively participate and support the palm oil business. Not a corporation, but the commodity.

- o

- Use endorsers who are quite reputable in environmental sectors but also somebody to whom the community can relate.

- Experiential marketing

- o

- Storytelling and real experience can make a huge difference. By inviting certain representatives from the government, the buyers, and the end users, consumers can feel and experience life at the plantation and directly see the positive impact one has on the ground, and this will create and convey a different story altogether.

- Digital marketing

- o

- Unique and continuous digital marketing which may include different platforms can be used, but the message has to be clear, concise, and relevant to the changes and issues at hand.

- o

- A form of relatability and involvement can be created through this platform where end users can react, understand, ask questions, and ultimately be involved.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GAPKI. Palm Oil Contributes 15% of Indonesian Export. 2020. Available online: https://gapki.id/en/news/19427/palm-oil-contributes-15-of-indonesian-exports (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Saputra, D. Menko Airlangga Tegaskan Kontribusi Sawit untuk PDB Indonesia Capai 3,5 Persen. 2021. Available online: https://ekonomi.bisnis.com/read/20211117/9/1467135/menko-airlangga-tegaskan-kontribusi-sawit-untuk-pdb-indonesia-capai-35-persen (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Carter, C.; Finley, W.; Fry, J.; Jackson, D.; Willis, L. Palm oil markets and future supply. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2007, 4, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, R.M.; Durán, A.P.; Rademacher, T.T.; Martin, P.; Tayleur, C.; Brooks, S.E.; Coomes, D.; Donald, P.F.; Sanderson, F.J. The environmental impacts of palm oil and its alternatives. bioRxiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gaveau, D.; Locatelli, B.; Salim, M.; Husnayaen, H.; Manurung, T.; Descals, A.; Angelsen, A.; Meijaard, E.; Sheil, D. Slowing deforestation in Indonesia follows declining oil palm expansion and lower oil prices. PLoS ONE 2021, 17, e0266178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, V.; Pimm, S.; Jenkins, C.; Smith, S. The Impacts of Oil Palm on Recent Deforestation and Biodiversity Loss. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margono, B.A.; Potapov, P.V.; Turubanova, S.; Stolle, F.; Hansen, M.C. Primary Forest cover loss in Indonesia over 2000–2012. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, J.; Hooijer, A.; Vernimmen, R.; Liew, S.C.; Page, S.E. From carbon sink to carbon source: Extensive peat oxidation in insular Southeast Asia since 1990. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 024014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenpeace Indonesia. Terobosan Baru Wilmar Agar Para Perusak Hutan Tidak Dapat Bersembunyi. 2018. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/indonesia/siaran-pers/1127/terobosan-baru-wilmar-agar-para-perusak-hutan-tidak-dapat-bersembunyi/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Sitepu, M. Greenpeace Tuntut IOI Putus Kontrak Perusahaan Sawit Pembakar Hutan. 2016. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/berita_indonesia/2016/10/160927_indonesia_greenpeace_laporan (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- DetikNews. Spanduk Greenpeace Dicopot Paksa dari Plaza BII. 2009. Available online: https://news.detik.com/berita/d-1101753/spanduk-greenpeace-dicopot-paksa-dari-plaza-bii (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Arief, R.; Cangara, A.; Badu, M.; Baharuddin, A.; Apriliani, A. The impact of the European Union (EU) renewable energy directive policy on the management of Indonesian palm oil industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 575, 012230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveer, P. Sustainability Of Palm Oil And Its Acceptance In The EU. J. Oil Palm Res. 2020, 32, 365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Khatun, R.; Reza, M.I.H.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Yaakob, Z. Sustainable oil palm industry: The possibilities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiawan, R.; Limaho, H. The Importance of Co-opetition of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia. Corp. Trade Law Rev. 2020, 1, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Boons, F.; Mendoza, A. Constructing sustainable palm oil: How actors define sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1686–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Parvatiyar, A. Sustainable marketing: Market-driving, not market-driven. J. Macromark. 2020, 41, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.; Tomas, M.; Jeannette, A.; Mena, M.; Perez, A.G.; Lagerstro, K.; Hult, D.T. A Ten Country-Company Study of Sustainability and Product-Market Performance: Influences of Doing Good, Warm Glow, and Price Fairness. J. Macromark. 2018, 38, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. Sustainable Marketing, Equity, and Economic Growth: A Resource-Advantage, Economic Freedom Approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up? Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Elkinton, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Wiley: Oxford, UK; London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Amos, O.A.; Uniamikogbo, E. Sustainability and Triple Bottom Line: An Overview of Two Interrelated Concepts. Igbinedion Univ. J. Account. 2016, 2, 88–126. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. 25 Years Ago, I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It. Harvard Business Review. 2018. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Ernah, P.P.; Waibel, H. Adoption of sustainable palm oil practices by Indonesian smallholder farmers. Southeast Asian Econ. 2016, 33, 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hutabarat, S. ISPO certification and Indonesian oil palm competitiveness in global market: Smallholder challenges toward ISPO certification. Agro Ekon. 2017, 28, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astari, A.J.; Lovett, J.C. Does the rise of transnational governance ‘hollow-out’ the state? Discourse analysis of the mandatory Indonesian sustainable palm oil policy. World Dev. 2019, 117, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessen, L.; Burns, S.; Sahide, M.A.K.; Wibowo, A. From governance to government: The strengthened role of state bureaucracies in forest and agricultural certification. Policy Soc. 2016, 35, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, V.; Richards, C. Framing sustainability: Alternative standards schemes for sustainable palm oil and south-south trade. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvia, N.; Rinaldi, W.; Muslim, A.; Yunardi, H.H. Challenges and possibilities of implementing sustainable palm oil industry in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 969, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, G.; Glasbergen, P. Creating legitimacy in global private governance: The case of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiawan, R. Conservation and Development Balance of the Palm Oil Industry Through Sustainability Regulation. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2019, 358, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- May-Toben, C.; Goodman, L.K. Donuts, Deodorant, Deforestation: Scoring America’s Top Brands on Their Palm Oil Commitments; Union of Concerned Scientists: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greenpeace International. Certifying Destruction: Why Companies Need to Go Beyond the RSPO to Stop Forest Destruction; Greenpeace: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cazzolla Gatti, R.; Liang, J.; Velichevskaya, A.; Zhou, M. Sustainable palm oil may not be so sustainable. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prothero, A. Green consumerism and the societal marketing concept: Marketing strategies for the 1990s. J. Mark. Manag. 1990, 6, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pride, W.M.; Ferrell, O.C. Marketing, 8th ed.; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Rosenberger, P. Re-evaluating green marketing: A strategic approach. Bus. Horiz. 2001, 44, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P. The Virtuous Spiral: A Guide to Sustainability for NGOs in International Development; Fowler, A., Ed.; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2003; Volume 35, pp. 280–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.; Carrigan, M.; Hastings, G. A framework for sustainable marketing. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Golden goose or wild goose? The hunt for the green consumer. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varey, R.J. Marketing means and ends for a sustainable society: A welfare agenda for transformative change. J. Macromark. 2010, 30, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.A.; Ottman, J.A. Moderating unintended pollution: The role of sustainable product design. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A. Marketing for sustainability: Extending the conceptualisation of the marketing mix to drive value for individuals and society at large. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Achrol, R.S.; Kotler, P. Frontiers of the marketing paradigm in the third millennium. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M. Market-focused sustainability: Market orientation plus! J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Belz, F. Sustainability marketing—An innovative conception of marketing. Mark. Rev. St. Gallen 2010, 27, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, E.J. Basic Marketing. Richard D. Irwin, Inc.: Homewood, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, F.M.; Peattie, K. Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Govender, J.P.; Govender, T.L. The influence of green marketing on consumer purchase behavior. Environ. Econ. 2016, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, C.F.; Lee, B.C.Y.; Kou, T.C.; Wu, C.K. Green Marketing: The Roles of Appeal Type and Price Level. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2014, 4, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Singh, R.; Sharma, S. Emergence of Green marketing Strategies and Sustainable Development in India. J. Commer. Manag. Thought 2016, 7, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Datta, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Hannigan, R. An Integrated Approach to Environmental Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.; Montiel, I. When Are Corporate Environmental Policies a Form of Greenwashing? Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 377–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzeł, B.; Wolniak, R. The Greenwashing Customer’s Awareness Research. Taras Shevchenko. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Social Sciences, Nanjing, China, 4–5 April 2021; Volume 3, pp. 1064–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Griese, K.; Werner, K.; Hogg, J. Avoiding Greenwashing in Event Marketing: An Exploration of Concepts, Literature and Methods. J. Manag. Sustain. 2017, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blery, E.K.; Katseli, E.; Tsara, N. Marketing for a non-profit organization. Int. Rev. Public Non-Profit Mark. 2010, 7, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, P.; Vambery, R.G. Aligning Global Business Strategy Planning Models with Accelerating Change. J. Glob. Bus. Technol. 2008, 4, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sron, B. Headwinds in Palm Oil Industry Will Persist. 2018. Available online: http://gofbonline.com/headwinds-in-palm-oil-industry-will-persist/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Widyasari, I.; Anindita, L. Strategi Media Relations Greenpeace Indonesia Dalam Meningkatkan Citra Organisasi. Communication 2022, 11, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Naim Nor-Ahmad, S.N.H.J.; Amran, A.; Khalid, N.A.; Rahman, R.A. What Drives and Impede Change Towards Sustainable Palm Oil? In Proceedings of the 4th UUM International Qualitative Research Conference (QRC 2020), Virtual Conference, 1–3 December 2020; pp. 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, K. Greenpeace Slams HSBC for Funding Destructive Indonesian Palm Oil Firms. 2017. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-palmoil-hsbc-idUSKBN151 (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Chaudari, A. Greenpeace, Nestle and the Palm Oil Controversy: Social Media Driving Change? IBS Cent. Manag. Res. 2011, 911-010-1, 1–24. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwi8xfnhgvX4AhULyGEKHeGVCDgQFnoECAIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bu.edu%2Fgoglobal%2Fa%2Fpresentations%2Fgreenpeace_nestle_socialmedia.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0J1lKMx6ZwbZO6S_W2vJjZ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Noor, D.A. Indonesia Palm Oil as Issue Insight of Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Environmental Science and Sustainable Development, ICESSD 2019, Jakarta, Indonesia, 22–23 October 2019; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg, J.M.; Bloom, P.N. Choosing the Right Green Marketing Strategy. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburger, A.M.; Nalebuff, B.J. Co-Opetition; Doubleday Currency: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, M. Use Co-Opetition to Build New Lines of Revenue. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburger, A.M.; Nalebuff, B.J. The Rules of Co-opetition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2021, 99, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mosad, Z. Co-opetition: The Organisation of the Future. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2004, 22, 780–790. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M.; Pfitzer, M. The Ecosystem of Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmar International. No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation Policy. 2013. Available online: https://www.wilmar-international.com/sustainability/policies (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- McKnight, D.; Hobbs, M. Fighting for Coal: Public Relations and the Campaigns Against Lower Carbon Pollution Policies in Australia. In Carbon Capitalism and Communication; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Limaho, H.; Sugiarto; Pramono, R.; Christiawan, R. The Need for Global Green Marketing for the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148621

Limaho H, Sugiarto, Pramono R, Christiawan R. The Need for Global Green Marketing for the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148621

Chicago/Turabian StyleLimaho, Handoko, Sugiarto, Rudy Pramono, and Rio Christiawan. 2022. "The Need for Global Green Marketing for the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148621

APA StyleLimaho, H., Sugiarto, Pramono, R., & Christiawan, R. (2022). The Need for Global Green Marketing for the Palm Oil Industry in Indonesia. Sustainability, 14(14), 8621. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148621