Financial Support for Neighborhood Regeneration: A Case Study of Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Definition and Status of Urban Regeneration

2.2. The Status and Recent Trend of Neighborhood Regeneration

2.3. Financial Support for Neighborhood Regeneration

3. Research Questions

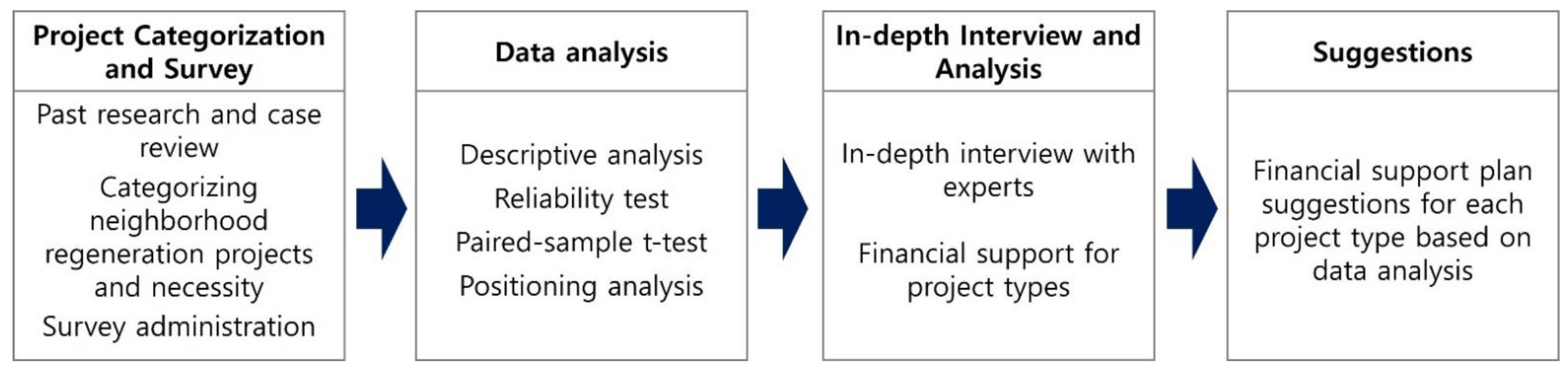

4. Method

4.1. Project and Item Design for Neighborhood Regeneration

4.2. Data Collection from a Survey and In-Depth Interviews

4.3. Measurements of Survey Items and In-Depth Interview Questions

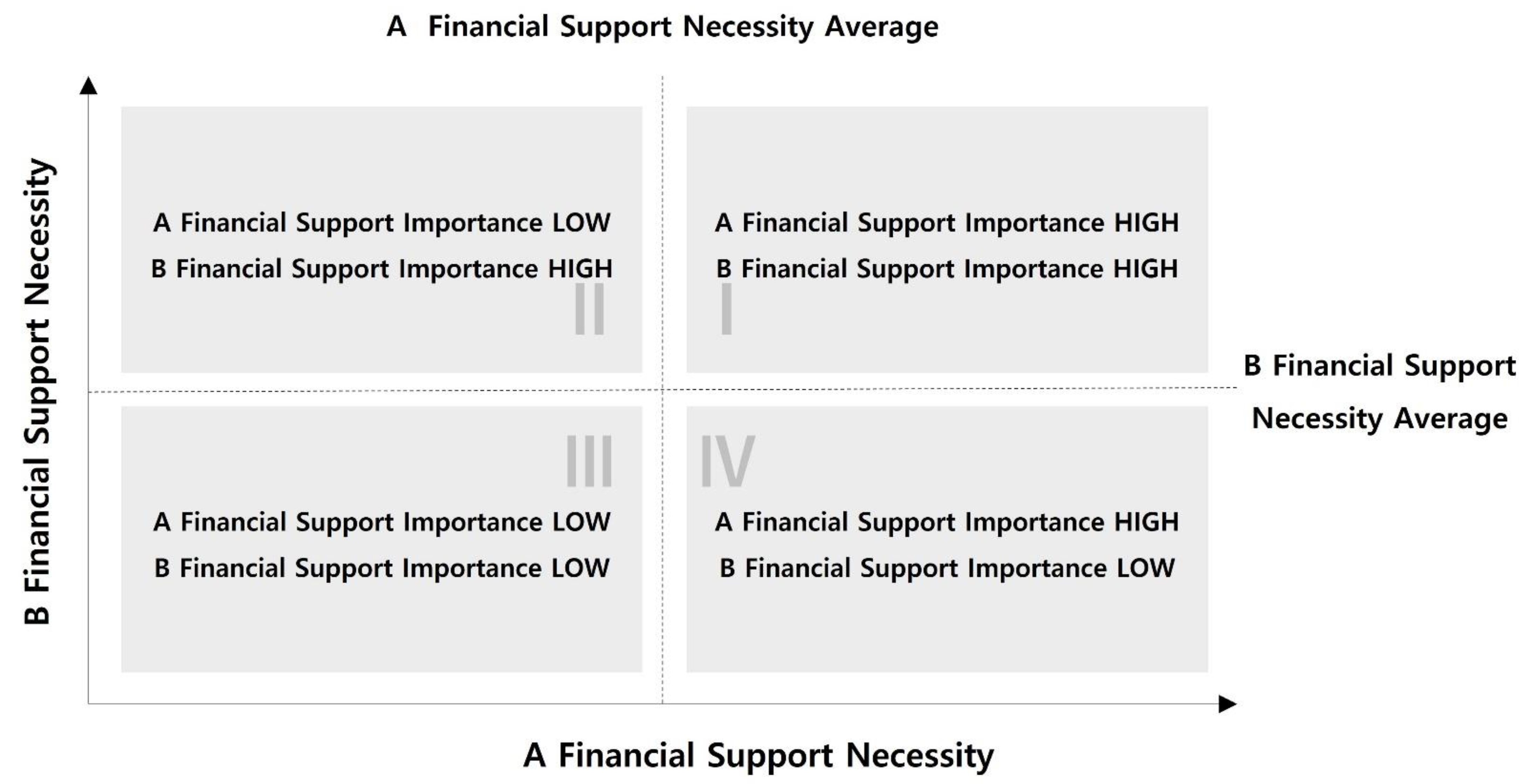

4.4. Data Analysis Plan

5. Findings

5.1. Sample Characteristics

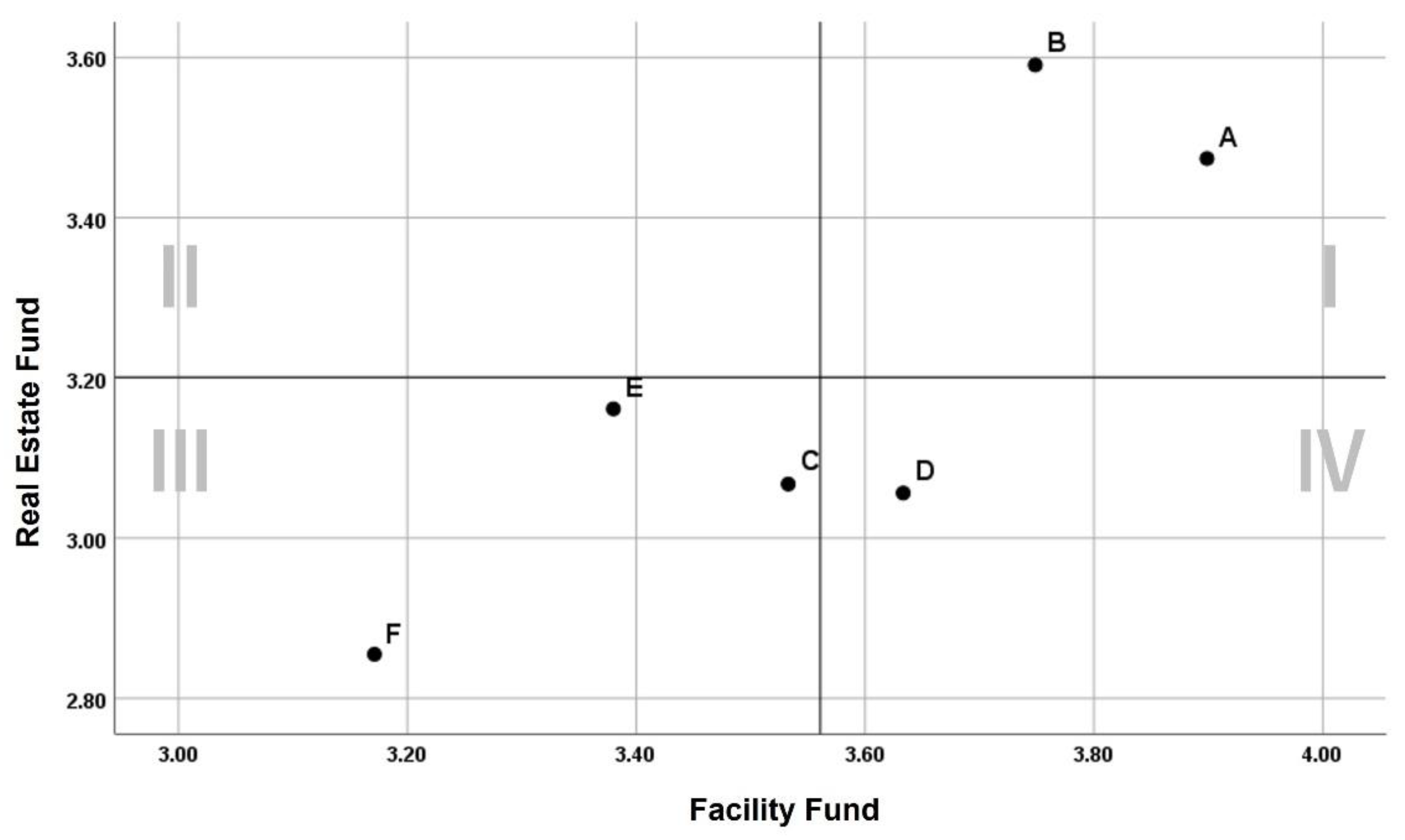

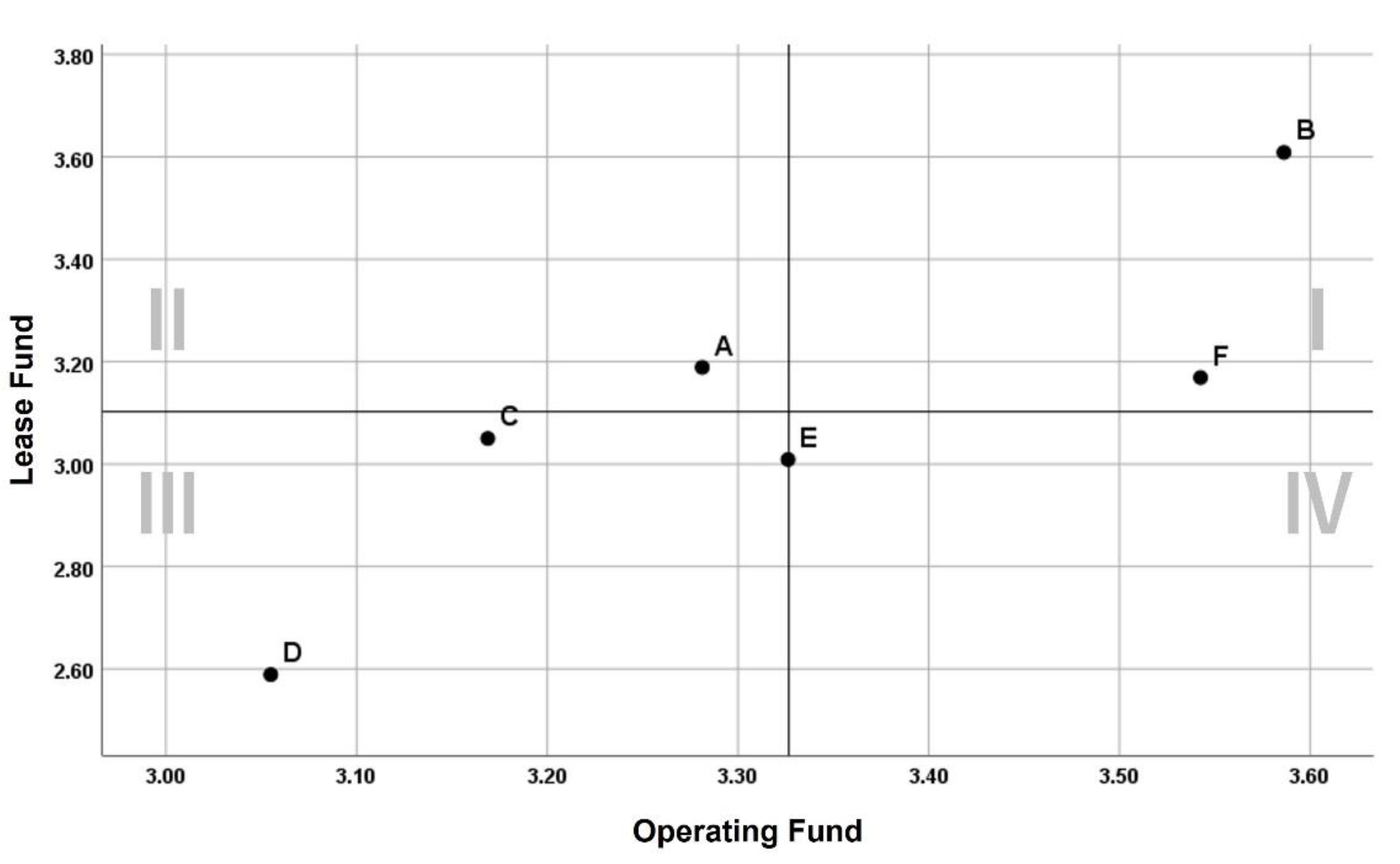

5.2. Answers for Research Questions

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications of Findings

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type | Detailed Items |

|---|---|

| A. Housing Vitalization Project | 1. Creating complex residential facilities with diverse classes, including socially vulnerable and low-income groups 2. Creating social rental housing and cooperative housing facilities for marginal populations, including the youth and the elderly 3. Creating facilities that adopt eco-friendly remodeling technology for energy efficiency in old residential areas 4. Supporting internal and external renovation to improve the landscape and functions of old dense residential areas 5. Supporting the improvement and utilization of unoccupied residential facilities in areas 6. Creating job-housing proximity to residential facilities where work and housing can be done in the same place 7. Creating residential facilities where people from similar industries can form a local network 8. Creating residential facilities including unoccupied space, common kitchen, laundry site, and others |

| B. Private Sector Participation Project | 1. Creating a space for young people and startups that produce jobs and induce business participation 2. Creating a start-up space that can vitalize the local industry 3. Creating anchor facilities such as neighborhood regeneration hubs that anyone can easily use 4. Creating neighborhood regeneration support centers and a workplace for local regeneration companies 5. Creating a collective shopping district to implement a coexistence agreement on rent for gentrification prevention 6. Creating local asset utilization facilities owned by residents for gentrification prevention 7. Creating jobs, joint workshops, and joint sales venues to foster self-sustaining organizations 8. Creating a culture and arts village that combines exhibitions, sales, and residential functions for artists |

| C. Local Economy Vitalization Project | 1. Creating resident networks connected to local assets to promote local tourism 2. Creating tourism support-related facilities, such as guest houses, to promote tourism in the region 3. Creating a space for start-ups in traditional markets to revitalize local commercial districts 4. Renovating traditional markets and old shopping districts to revitalize local commercial districts 5. Establishing and operating a regional economic community revitalization program for the revitalization of local commercial districts 6. Establishing flea markets and space to promote start-ups and local residents’ profits 7. Creating a plaza that specializes in selling local specialty products to strengthen regional competitiveness 8. Renovating commercial facilities on the streets using vacant stores to revitalize the local economy |

| D. Local Living Improvement Project | 1. Creating a safe traffic environment for vulnerable pedestrians such as children, the elderly, the disabled, etc. 2. Installing landmark sculptures reflecting on local culture and arts to create an inviting environment 3. Fostering a crime-free environment for the prevention of local crimes and the reduction of crime uncertainty (CPTED) 4. Establishing systems and infrastructure for disaster prevention management and response, such as disaster safety management 5. Creating and operating local upbringing and childcare facilities for the health and childcare support of local infants and toddlers 6. Developing youth culture and education facilities for the regeneration of the community in the culturally disadvantaged areas 7. Maintaining local infrastructure, such as road facilities, sewer systems, and telecommunications, for the improvement of living conditions 8. Creating community facilities (garden, park, parking lot) that recycle abandoned public properties and houses |

| E. Local Living Network Project | 1. Creating community facilities for the improvement of residents’ living welfare 2. Creating a cultural network center reflecting on diverse cultures in the community 3. Creating a communal urban garden and a work facility where residents can participate 4. Operating and supporting cross-regional cultural exchange programs and facilities that use local assets 5. Operating and supporting community revitalization programs and resident-led projects 6. Operating and supporting network formation programs and facilities for local residents and migrants 7. Operating and supporting neighborhood regeneration education/exchange programs for the development of resident-led villages 8. Operating and supporting cultural arts education programs and facilities that expand opportunities for enjoyment of culture |

| F. Local Economy Operation Project | 1. Operating and supporting renovation education programs and facilities that remodel unused buildings 2. Operating and supporting programs to foster social economic players and facilities that contribute to the local economy. 3. Operating and supporting employment platforms centered on local companies and facilities for job creation in the region 4. Operating and supporting festival programs and facilities that revitalize the local economy 5. Operating and supporting intermediary platforms and facilities that provide unoccupied building information to users 6. Creating and supporting shared spaces that enable co-working and co-living for the vitalization of the sharing economy 7. Operating and supporting vocational education programs for residents and facilities for sustainable local development 8. Operating and supporting the shared economy academy program and facilities for the revitalization of the local economy |

Appendix B

- What is your opinion on the financial support plans for the housing vitalization project?

- What is your opinion on the financial support plans for the private sector participation project?

- What is your opinion on the financial support plans for the local economy vitalization project?

- What is your opinion on the financial support plans for the local living improvement project?

- What is your opinion on the financial support plans for the local living network project?

- What is your opinion on the financial support plans for the local economy operation project?

- What is your opinion on the financial support plans to vitalize neighborhood regeneration projects?

References

- Martinović, A.; Ifko, S. Industrial heritage as a catalyst for urban regeneration in post-conflict cities Case study: Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cities 2018, 74, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manupati, V.K.; Ramkumar, M.; Samanta, D.A. Multi-criteria decision-making approach for the urban renewal in Southern India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea City Regeneration Total Information System. What Is Urban Regeneration? Urban Regeneration Support Organization and Centers. Available online: https://www.city.go.kr/portal/policyInfo/urban/contents05/link.do (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Salingaros, N.A.; Kryazheva, Y.; Rudd, A. A New Pattern Language for Growing Regions: Places, Networks, Processes; Sustasis Press: White Salmon, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, M.V. Theory of attachment and place attachment. In Psychological Theories for Environmental Issues; Bonnes, T.L., Bonnes, M.B.M., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2002; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Galster, G. On the nature of neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, P.; García-Mayor, C.; Serrano-Estrada, L. Identifying opportunity places for urban regeneration through LBSNs. Cities 2019, 90, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.B. Definition of urban regeneration project in neighborhood regeneration and its method of business. In Planning for New Urban Regeneration; Hanul: Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.Y.; Ahn, J.S. A study on neighboring regenerative-type urban regeneration: A case of the Changsin-Sungin Regions in Seoul. J. Photo Geogr. 2016, 26, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, W.B. Seoul Social Economy Coordinator Training Course; Seoul Metropolitan City Social Economy Support Center Press: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, K.S. Daein art market projects and sustainable urban regeneration in Gwangju metropolitan city. J. Korean Urban Geogr. Soc. 2016, 19, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, C.; Balaban, O. Sustainability of urban regeneration in Turkey: Assessing the performance of the North Ankara Urban Regeneration Project. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingaertner, C.; Barber, A. Urban regeneration and socio-economic sustainability: A role for established small food outlets. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1653–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Newman, G.; Jiang, B. Urban regeneration: Community engagement process for vacant land in declining cities. Cities 2020, 102, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accordino, J.; Johnson, G.T. Addressing the vacant and abandoned property problem. J. Urban Aff. 2000, 22, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J.; Mallach, A. Cities in Transition: A Guide for Practicing Planners; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; Volume 568. [Google Scholar]

- Güzey, O. Urban regeneration and increased competitive power: Ankara in an era of globalization. Cities 2009, 26, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.E.; McCarthy, J. Introduction urban regeneration a global phenomenon. In The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration; Leary, M.E., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, A.R.; Yoo, H.Y. A study of the policy improvement for the housing area as the urban regeneration of the new deal project. JAIK 2018, 34, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.P. Sustainable regeneration. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Lovell, H., Elsenga, M., Smith, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Lim, S. An Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Approach for Sustainable Assessment Of Economy-Based And Community-Based Urban Regeneration: The Case Of South Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4456. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.H. Upgrading the Santa Marta Favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Focusing on the roles of various sectors in slum upgrading. Urban Des. 2014, 15, 155–171. [Google Scholar]

- Dargan, L. Participation and local urban regeneration: The case of the New Deal for Communities (NDC) in the UK. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pares, M.; Bonet-Marti, J.; Marti-Costa, M. Does participation matter in urban regeneration policies? Exploring governance networks in Catalonia (Spain). Urban Aff. Rev. 2012, 48, 238–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. A Study on the establishment of renewal strategy for local cities and the promotion of urban regeneration project. J. Korean Reg. Dev. Assoc. 2012, Fall, 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, S.; Kıvrak, S.; Gültekin, A.B.; Arslan, G. Built environment design-social sustainability relation in urban renewal. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.T. Smart city and governance: A case of Barcelona. J. Korean Urban Manag. 2016, 29, 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.J.; Yoon, J.S. Development of Neighborhood Regeneration Fund Support Programs to Revitalize Urban Regeneration; Architecture & Urban Research Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Liu, G.; Zhuang, T. A Comprehensive Review of Urban Regeneration Governance for Developing Appropriate Governance Arrangements. Land 2021, 10, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.R.; Magalhaes, F. Upgrading Squatter Settlements into City Neighborhoods: The Favela-Bairro Program in Rio de Janeiro’ in Contemporary Urbanism Brazil: Beyond Brasilia; William, S., Ed.; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, F.; Acosta Restrepo, P.; Lonardoni, F.; Moris, R. Slum Upgrading and Housing in Latin America; Inter-American Development Bank Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Architecture & Urban Research Institute. Case Study of Village Regeneration 1: Ten Keywords For Place-Centered Village Regeneration; Architecture & Urban Research Institute Press: Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, S.E. Building Community Capacity: The Potential of Community Foundation; Rainbow Research: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Della Spina, L. Multidimensional assessment for “culture-led” and “community-driven” urban regeneration as driver for trigger economic vitality in urban historic centers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korea Housing & Urban Guarantee Corporation. National Housing & Urban Fund Product Utilization Casebook; The Ministry of Land and Transportation Press: Seoul, Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Unbounded Inspiring Space. Available online: https://www.cosmo40.com/ (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Haselsteiner, E.; Rizvanolli, B.V.; Villoria Sáez, P.; Kontovourkis, O. Drivers and Barriers Leading to a Successful Paradigm Shift toward Regenerative Neighborhoods. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.J.; Bae, J.A.; Kim, H.S. A Study on a Regeneration Master Plan of Aging Residence areas: Jeonju City Nosong-Dong. J. Rec. Lan. 2013, 7, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.J.; Yoon, J.S. Neighborhood Regeneration Program Development for Urban Regeneration Vitalization; Architecture Urban Space Institute: Coimbatore, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Nah, I.S. An Analysis of Social Economic Traits in Urban Regeneration Vitalization Projects: The Case of Incheon Metropolitan City. J. Reg. Assoc. Arch. Korean 2019, 21, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, E.Y.; Byun, B.S. The Impact of Characteristics of Social Enterprise on its Performance and Sustainability. J. Korean Reg. Dev. 2013, 29, 69–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, W.J.; Moon, S.B. A Study on Possibility of Social Enterprise as a main participant in Urban Renaissance: Based on the Analysis of the Importance of Business Links. J. Korean Cad. Inf. 2010, 12, 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, L.; Michell, K.; Viruly, F. A Critique of The Application Of Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment Tools In Urban Regeneration. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGreal, S.; Adair, A.; Berry, J.; Deddis, B.; Hirst, S. Accessing private sector finance in urban regeneration: Investor and non-investor perspectives. J. Prop. Res. 2000, 17, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea National Housing Fund Urban Regeneration Portal. The Role of the Korea Housing & Urban Guarantee Corporation That Carries Out the National Housing Urban Fund. Korea National Housing Fund Urban Regeneration. Available online: http://nhuf.molit.go.kr/FP/FP04/FP0401/FP040102.jsp (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Varady, D.; Kleinhans, R.; Van Ham, M. The potential of community entrepreneurship for neighbourhood revitalization in the United Kingdom and the United States. In Entrepreneurial Neighbourhoods; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.Y. A Study on the Improvement of the State’s Financial Support System for Urban Regeneration Projects; Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements: Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, L.; Rydin, Y. Urban sustainability: Discourses, networks and policy tools. Prog. Plann. 1997, 47, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H. Design and management of complex anchor facility in urban regeneration—Focused on the urban regeneration project in Chung-buk. J. Korean Cadastre Inf. Assoc. 2020, 22, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.H. The change of urban regeneration new deal policy and the role of local public enterprises. Pub. Pol. 2021, 193, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Jung, E.J. Policy plans to fulfill the virtuous circle of urban regeneration projects. KRIHS Policy Brief 2021, 835, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.W.; McCarty, A.D.; Lee, J. Enhancing sustainable urban regeneration through smart technologies: An assessment of local urban regeneration strategic plans in Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y. The challenges of the United Nations Habitat’s strategic plan and Korea’s urban regeneration. Pub. Pol. 2020, 179, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

| Types of Neighborhood Regeneration Projects | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Supports housing, constructs social infrastructure, and secures stable living for underserved populations |

| Creates facilities to support private entities for sustainable neighborhood regeneration |

| Improves commercial and tourist facilities and local assets to promote the local economy |

| Creates a convenient and safe living environment |

| Supports residents for networking and resident-led neighborhood projects |

| Develops and operates local economy programs for growing private entities |

| Last Name | Affiliation | Position | Level of Education | Total Employment History (Related to Neighborhood Regeneration) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lee | Public institution (fund) | Team leader | Master | 19 (12) |

| 2 | Cho | Public institution (fund) | Team leader | Master | 14 (10) |

| 3 | Baek | Public institution (Project entity) | Team leader | Doctorate | 17 (7) |

| 4 | Seok | Public institution (Project entity) | Deputy department head | Master | 18 (4) |

| 5 | Son | Private expert | Director | Doctorate | 14 (9) |

| 6 | Lee | Private expert | CEO | Doctorate | 10 (10) |

| 7 | Jang | Local government | Section chief | Doctorate | 30 (10) |

| 8 | Jeon | Local government | Action officer | Doctorate | 14 (11) |

| 9 | Lee | Neighborhood regeneration support center | Head of the center | Doctorate | 20 (12) |

| 10 | Lee | Neighborhood regeneration support center | Team leader | Doctorate | 22 (12) |

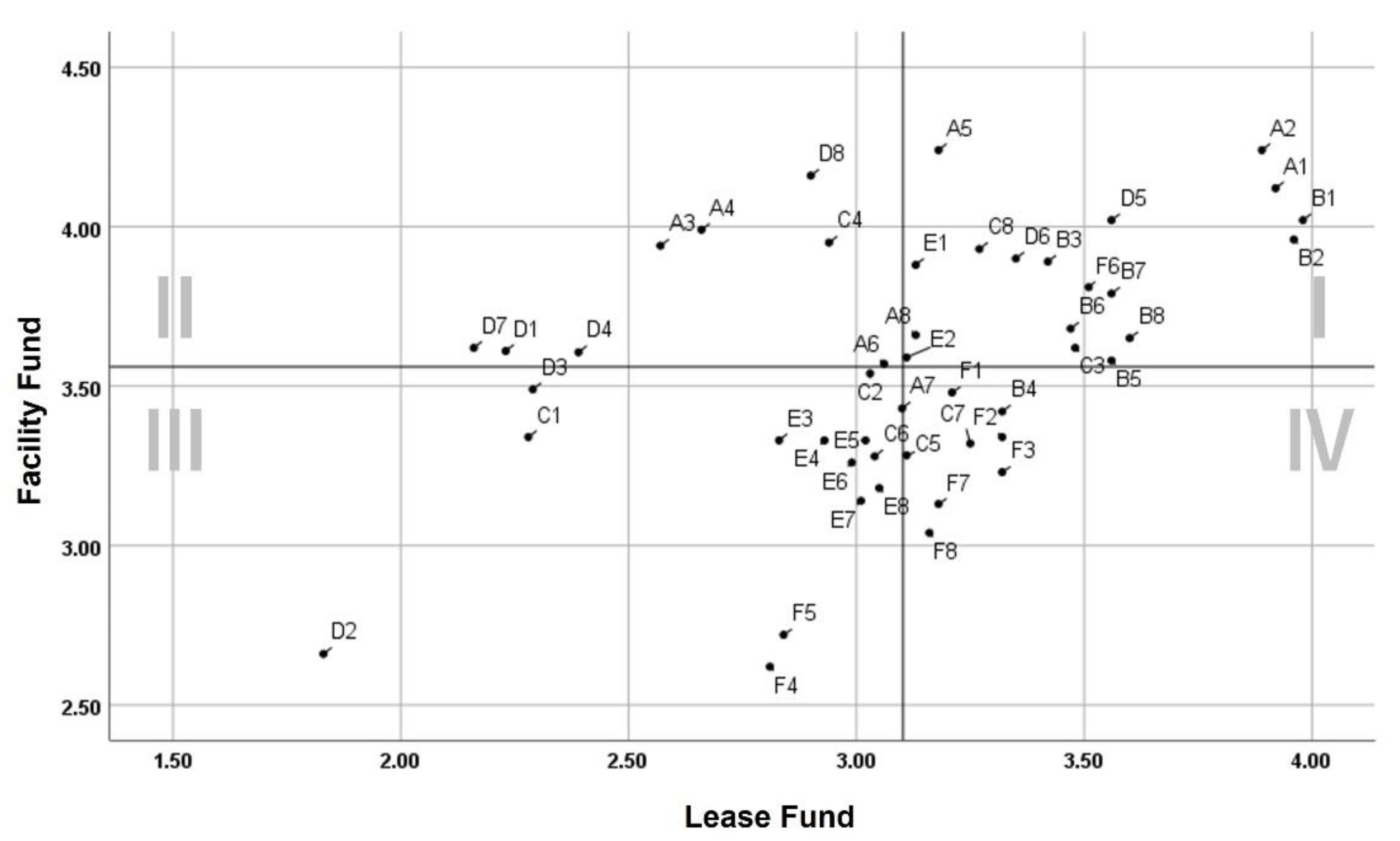

| Projects | Real Estate Fund | Facility Fund | Lease Fund | Operating Fund | Total Avg. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Housing vitalization project | 3.47 | 3.90 | 3.19 | 3.28 | 3.46 |

| B | Private sector participation project | 3.59 | 3.75 | 3.61 | 3.59 | 3.63 |

| C | Local economy vitalization project | 3.07 | 3.53 | 3.05 | 3.17 | 3.20 |

| D | Local living improvement project | 3.06 | 3.63 | 2.59 | 3.06 | 3.08 |

| E | Local living network project | 3.16 | 3.38 | 3.01 | 3.33 | 3.22 |

| F | Local economy operation project | 2.86 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.54 | 3.18 |

| Total avg. | 3.20 | 3.56 | 3.10 | 3.33 | 3.30 | |

| Section | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Housing vitalization project | Facility fund * | Real estate fund * | Operating fund | Lease fund |

| B | Private sector participation project | Facility fund * | Lease fund * | Real estate fund, operating fund * | - |

| C | Local economy vitalization project | Facility fund * | Operating fund | Real estate fund | Lease fund |

| D | Local living improvement project | Facility fund * | Real estate fund, operating fund | Lease fund | - |

| E | Local living network project | Facility fund * | Operating fund * | Real estate fund | Lease fund |

| F | Local economy operation project | Operating fund * | Facility fund, lease fund | Real estate fund | - |

| Funds | Difference in Response | t | d.f. | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | SD | Avg. SD | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference in Response | |||||

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||||

| Real estate fund—Facility fund | −0.360 * | 0.158 | 0.065 | −0.526 | −0.194 | −5.579 | 5 | 0.003 |

| Real estate fund—Lease fund | 0.098 | 0.270 | 0.110 | −0.185 | 0.382 | 0.893 | 5 | 0.413 |

| Real estate fund—Operating fund | −0.126 | 0.301 | 0.123 | −0.441 | 0.190 | −1.026 | 5 | 0.352 |

| Facility fund—Lease fund | 0.459 * | 0.381 | 0.155 | 0.059 | 0.858 | 2.951 | 5 | 0.032 |

| Facility fund—Operating fund | 0.234 | 0.371 | 0.151 | −0.155 | 0.623 | 1.548 | 5 | 0.182 |

| Lease fund—Operating fund | −0.224 * | 0.189 | 0.077 | −0.423 | −0.026 | −2.905 | 5 | 0.034 |

| Section | A Housing Vitalization Project | B Private Sector Participation Project | C Local Economy Vitalization Project | D Local Living Improvement Project | E Local Living Network Project | F Local Economy Operation Project |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real estate fund + facility fund | 1, 2, 5, 8 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 3, 8 | 5, 6, 8 | 1, 2 | 6 |

| Facility fund + lease fund | 1, 2, 5, 8 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 3, 8 | 5, 6 | 1, 2 | - |

| Lease fund + operating fund | 1, 2, 5, 8 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 | 3 | 5, 6 | 1, 2 | 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8 |

| Real estate fund | 6, 7 | 4 | 2 | - | 3 | - |

| Facility fund | 3, 4, 6 | - | 4 | 1, 4, 7, 8 | - | - |

| Lease fund | - | 4, 5 | 5, 7, 8 | - | - | 1, 2, 3, 7, 8 |

| Operating fund | - | - | 5 | 8 | 5, 6, 7, 8 | 5 |

| Excluded items | - | - | 1, 6 | 2, 3 | 4 | 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.; Kim, K. Financial Support for Neighborhood Regeneration: A Case Study of Korea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148582

Kim D, Kim K. Financial Support for Neighborhood Regeneration: A Case Study of Korea. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148582

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Doil, and Kabsung Kim. 2022. "Financial Support for Neighborhood Regeneration: A Case Study of Korea" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148582

APA StyleKim, D., & Kim, K. (2022). Financial Support for Neighborhood Regeneration: A Case Study of Korea. Sustainability, 14(14), 8582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148582