Ecolodge Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets: A New Typology of Entrepreneurs; The Case of IRAN

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What motivated entrepreneurs to enter the ecolodge industry in emerging markets?

- What decision-making process did these entrepreneurs go through from idea formation to ecolodge establishment in emerging markets?

- What factors influenced their decision, and how did they perceive the impacts of ecolodge entrepreneurship in emerging markets?

- In these markets, can a typology of the entrepreneurs be developed based on the entrepreneurship process and ecolodge administration and services?

- What implications does this ideation and typology have for the development of authentic ecolodges in emerging markets?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Requirements of Ecolodges

2.2. Empirical Research on Ecolodge and Tourism Entrepreneurship

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Selection of Interviewees

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Drivers

4.1.1. Poor Working Conditions

“I went to several government departments for employment. Sometimes government jobs needed favoritism. Private companies pay too low salaries and just want to sign a one-sided contract right from the start.”

“I was working in a construction office in Tehran for a while. My boss had many irrelevant demands. For example, my work time was finished at 14 o’clock. He said you should sit here until 5pm. You’re not allowed to go. […] I couldn’t stand it anymore. I talked back and left.”

4.1.2. Economic Failure

“I used to be a floriculturist and green space contractor. I also had a plant nursery. But they didn’t pay me, and I decided to start a new job.”

4.1.3. Unfavorable Conditions for Livelihood Provision

“My husband is a worker. We had to do something. Otherwise, our home construction would not be completed with my husband’s previous earnings, i.e., wage labor. […] My husband did whatever he could, and spent his income on this house’s construction…”

4.1.4. Childhood Influences

“As a child, he loved wooden huts and even occasionally built small and miniature huts on his father’s farm.”

“My father used to rent a room in our house to tourists.”

4.1.5. Openness to Experience

4.1.6. Availability of Loans

“When we first went to the CHTO of Mazandaran, they said we would be given a loan. We were still assessing the probable benefits of an ecolodge business. When we saw that they were offering a low-interest loan, we were encouraged.”

“One of our relatives had come to us. He said that the CHTO of Mazandaran grants loans for traditional houses. He did not say what they were lending for. We said let’s get this loan and spend it to complete the construction of our new house while repairing this traditional house. But when we went there, they said you must establish an ecolodge in your traditional house.”

4.2. Entrepreneurs’ Motives

4.2.1. Making Money

4.2.2. Employment Creation

“I have three unemployed brothers. Really, they are not unemployed, but they work in the suburbs. I wanted them to have productive and decent employment here.”

“One of the things I wanted to do was create jobs. Now, every purchase I make or every guest I bring here benefits the people of this area.”

“I wanted to create a job for the people of this area. Tourists come here and buy dairy products. Its income benefits the villagers.”

4.2.3. Self-Reliance and Mastery

4.2.4. Social Interaction

4.2.5. Preservation of the Rural Lifestyle

“I want people to respect our lifestyle. I am determined to show them how hard we work.”

4.2.6. Protecting Cultural Heritage

“Our ancestors spent years trying to create this kind of architecture. Our job is to keep it.”

“I loved this house so much. I was upset and depressed when I saw the house being destroyed. I always wanted to repair it.”

4.2.7. Protecting the Environment

“If I serve urban people, they won’t buy land here and build a villa.”

4.3. Idea Sources

4.3.1. Experts at the CHTO of Mazandaran

“One of our families called his acquaintance at the CHTO of Mazandaran. We arranged an appointment for her to visit the house and give her opinion. For the first time, she introduced us to the idea of an ecolodge.”

“We wanted to establish a rural café. But when we went to CHTO of Mazandaran, they said that we have something called an ecolodge. You can get in this business.”

4.3.2. Advice of People Surrounding the Entrepreneur

“One of our families came to our house. We had just come here. She [explain who this is] said why don’t you rent this house to tourists? We said who’s coming here? She showed a lot of photos that tourists in Yazd and Isfahan are staying in traditional houses. She said it has a good revenue. Then we went to the CHTO of Mazandaran […].”

4.3.3. Observing Successful Models

“Someone here has a house. His wife is Venezuelan. Now they bring guests and receive considerable income from these stays. They are rich. They don’t accommodate Iranians.”

4.4. Context

4.4.1. Ownership of a Traditional House

“Basically, the ecolodge project sought to preserve the region’s traditional and indigenous architecture. For this reason, we do not grant licenses to those who want to build a modern ecolodge, because we are sure of the negative environmental and cultural effects of doing so. Since the launch of the ecolodge project in this province, about 80% of our requests have been for building a resort rather than enhancing the traditional houses and turning them into ecolodges.”

“We haven’t a traditional adobe house. It is cemented. We have just built it. It is not suitable for this business.”

“The tourist likes to see a mud and traditional house. Except these few houses [referring to old village houses], all have been destroyed.”

4.4.2. Having a Rural Background

“We do not playact. This is our life. If one comes from the city to start this, he has to pretend to be a villager. He can’t. That’s why it won’t work.”

4.4.3. High Potential of the Province as a Tourist Destination

4.4.4. Family Companionship

“We started the job with my wife. It is very important for me that she accepted to live in the village. […] There must be a couple to run an ecolodge. […] I couldn’t buy a manteaux for my wife for 3 years. We spent everything we earned here. […] Being a couple is very important to get started.”

“My husband left the house his father had bought for us in the city, and he came here to start the job with me.”

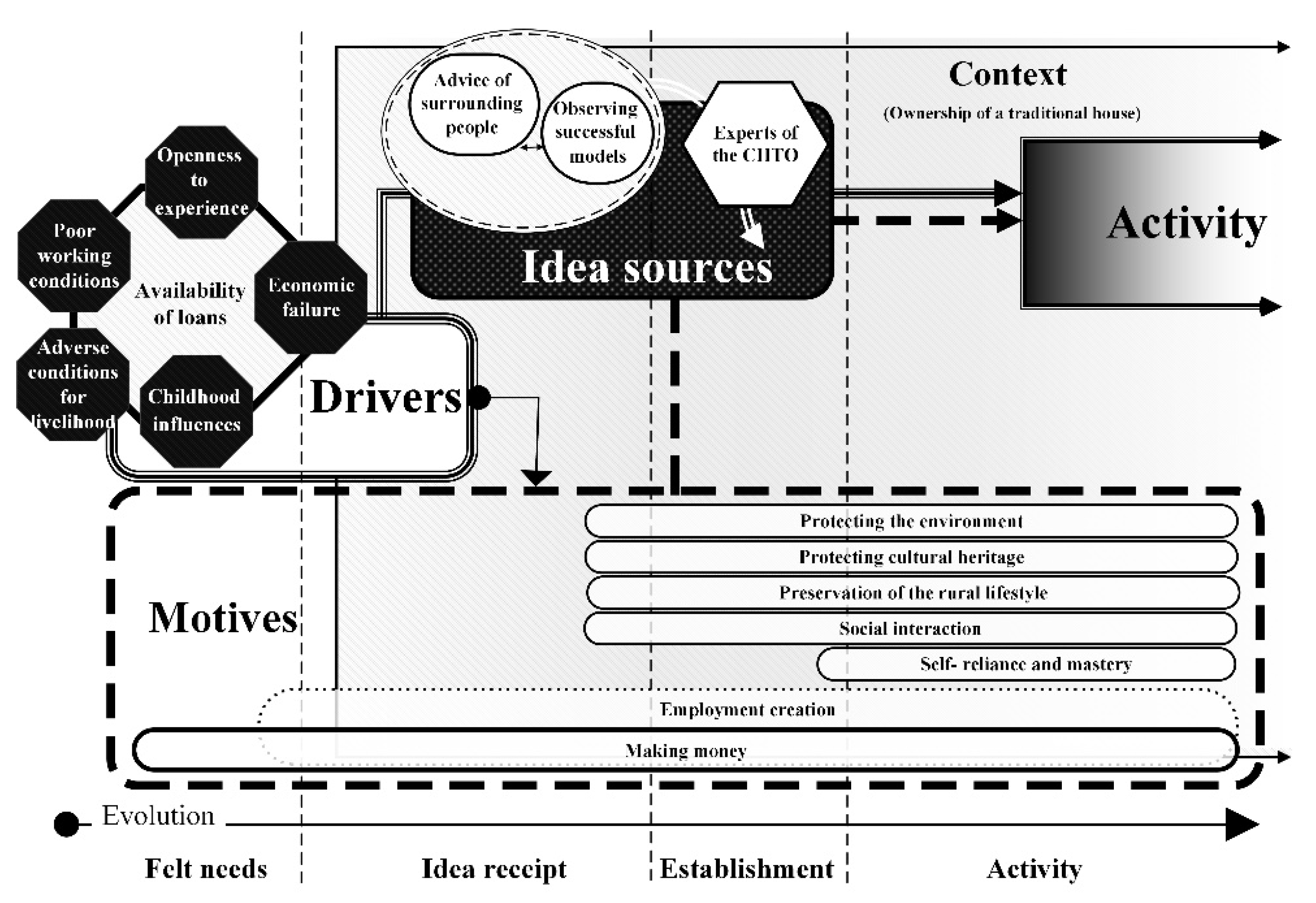

4.5. The Interaction Model of Ecolodge Entrepreneurship

- Initiating entrepreneurial activity with an economic motive, driven by an economic failure and/or availability of loans, receiving the idea of establishing an ecolodge from governmental experts, and relying on the use of a traditional house. This is the most common form of the entrepreneurial activity formation.

- Initiating entrepreneurial activity with non-economic motives, driven by openness to experience and childhood influences, receiving the idea of establishing an ecolodge by observing successful models, and relying on the rural background and family companionship. These motives include a mixture of social interaction, preservation of the rural lifestyle, job creation, and protection of cultural heritage and the environment. For example, pursuing childhood interests have pushed some entrepreneurs toward establishing an ecolodge to preserve the rural lifestyle.

4.6. Typology of Ecolodge Entrepreneurs

4.6.1. Ecolodge Lovers

4.6.2. Cool Job Seekers

4.6.3. Young Detached Entrepreneurs

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Entrepreneurs’ Entry into the Ecolodge Industry

- 1)

- 2)

- 3)

- 4)

- 5)

| Type | Author (s) | Main Objective | Sample | Analysis | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsustainable ecotourism business practices | Arze and Holladay [23] | Understanding the basic causes of unsustainable ecotourism business practices | Yacuma River Protected Area, Bolivia | Field note | Government is mostly focused on economic impacts of ecotourism businesses which are likely lose its market share due to environmental degradation. |

| Fennell and Markwell [76] | Understanding ethical and sustainability dimensions of foodservice in ecotourism businesses | 84 accredited Australian ecotourism businesses | Manifest content analysis | Very few ecotourism businesses have been mentioned ethical and sustainability dimensions of food on their websites. | |

| Higgins-Desbiolles [77] | Exploring nature of trade-offs between environmental conservation and greater economic growth through tourism development | 26 focused interviews with stakeholders of an ecolodge on Kangaroo Island, Australia | Case study analysis | Economic development has been promoted at the expense of the environment. | |

| Characteristics of ecotourists | Ban and Ramsaran [78] | Exploring service quality attributes of ecolodges | Interviews with 25 tourists | Qualitative coding and labeling | Compared to SERVPERF instrument, three additional dimensions were specific to the ecolodge sector. |

| Beaumont [79] | Investigating Pro-environmental attitudes among ecotourists | 243 domestic and international visitors of Lamington National Park, Australia | Quantitatively examining differences between visitors | No significant differences in pro-environmental attitudes between ecotourists and non-ecotourists. | |

| Brochado and Pereira [80] | Understanding consumers’ perceptions of services provided by glamping facilities | 172 comments rating glamping sites; 166 visitors staying in Portuguese glamping facilities | Content analysis and Exploratory factor analysis | Service quality in glamping was multidimensional, including five facets: staff, tangibles, food, nature-based experiences, and activities. | |

| Chan and Baum [81] | Exploring ecotourists’ perceptions of ecotourism experiences | Interviews with 29 European ecotourists staying at 2 ecolodges in Sukau, Lower Kinabatangan, Malaysia. | Qualitative analysis techniques | The preferred ecotourism activities included ecotourists’ physically engaging; interacting with the site service staff; socialising with other ecotourists, and acquiring information during the visit. | |

| Chan and Baum [39] | Exploring ecotourists’ motivation factors in the ecolodge accommodation | Interviews with 29 ecotourists staying in 2 ecolodges, Sukau, Malaysia | Qualitative phenomenological approach | Ecotourists were primarily attracted by the pull factors (destination attributes). | |

| Kwan, Eagles and Gebhardt [82] | Determining the characteristics and travel motivations of ecolodge patrons | 331 ecolodge patrons at 6 ecolodges, Cayo District, Belize | Chi-squared test or an ANOVA test | There were significant differences found in travel motivations and the importance of ecolodge attributes amongst the price levels. | |

| Kwan, Eagles and Gebhardt [83] | Determining the demographic and trip characteristics, and travel motivations of ecolodge patrons | 331 tourists who stayed at ecolodges, Cayo District of Belize | Importance – performance analysis | Ecolodge patrons were typically highly educated with high annual household income. Performance scores exceeded importance scores for all of ecolodge attributes. | |

| Lawton [84] | Profiling a sample of older adult ecotourist | 1140 ecolodge patrons, Lamington National Park, Australia | Chi-square or t tests | The older adult ecotourists preferred a higher level of comfort and less risk in comparison with the younger ecotourists. | |

| Lu and Stepchenkov [85] | Classifying satisfaction attributes with ecolodge stays | 373 reviews extracted from TripAdvisor | Content analysis and a two-step statistical procedure | Twenty-six ecotourists’ satisfaction attributes were identified and were classified into four groups: criticals, satisfiers, dissatisfiers, and neutrals. | |

| Mafi, Pratt and Trupp [86] | Exploring underlying satisfaction attributes of ecolodges | 11 guests in Matava ecolodge, island Kadavu, Fiji | Thematic analysis technique | There were emerging attributes that relate to local culture, local cuisine, local people engagement and remoteness. | |

| Newsome, Rodger, Pearce and Chan [87] | Understanding motivations and satisfaction of tourists with wildlife tourism experience | 346 visitors of eight lodges along the Kinabatangan River, Malaysia | Importance-performance matrix | The tourists, despite their satisfaction, were concerned about the number of boats and the protection of the River. | |

| Simpson et al., [88] | Identifying factors influencing revisit intention of ecolodge visitors | 362 visitors to Sri Lankan ecolodges | Structural modelling | Travel motives and satisfaction had a significant impact on tourist intentions to revisit individual ecolodges. | |

| Weaver and Lawton [89] | Segmenting overnight ecotourist market | 1800 tourists of ecolodges, Lamington National Park, Australia | Cluster analysis | The ecotourists were segmented into “harder”, “softer” and “structured” clusters. | |

| Weaver [90] | Identifying the characteristics of hard-core element within a special population of ecotourists | 1800 ecolodge patrons from two ecolodges, Lamington National Park, Australia | Cluster analysis | The hard-core ecotourists fitted in the expectations of the hard ecotourism ideal type. | |

| Conditions, performance and goals of ecolodges | de Grosbois and Fennell [91] | Identifying best practices in the sustainable management of the world leading ecolodges | 65 top global ecolodges | Qualitative content analysis | Key themes included biodiversity conservation, preserving socio-cultural heritage, improving social wellbeing, learning opportunities for guests, etc. |

| Hu et al. [92] | Exploring green attributes of an ecolodge | Triangulated sources of the organization’s publicity materials, online comments and observation from the Crosswaters Ecolodge and SPA, China | A multi-method qualitative study based on grounded theory | There were four green attributes: functional values, aesthetic values, psychological appeal, and experiential appeal. | |

| Lai and Shafer [15] | Exploring how ecotourism is marketed through the Internet | 35 ecolodge operators from 14 Latin America and the Caribbean | Content analysis | Most of the online marketing messages sent by the ecolodges only partially aligned with ecotourism principles. | |

| Mic and Eagles [93] | Investigating development of a cooperative brand strategy for midscale ecolodge businesses | 12 ecolodge owners and managers in Costa Rica | Thematic analysis | Individual operation of most ecolodges has imposed higher marketing and management costs. Development of a cooperative brand had challenges in 8 areas. | |

| Osland and Mackoy [18] | Discovering ecolodges’ performance goals and assessing their performance | Interviews with owners and managers of 21 ecolodges in Costa Rica and Mexico | Qualitative analysis techniques | A total of 84 performance goals were identified and classified using a new framework. | |

| Suarez-Dominguez, Argudo-Guevara and Arce-Bastidas [94] | Identifying important characteristics of ecolodge | Tourists who visited the Ecolodge Napo Wildlife Center, Ecuador | Content analysis | The location was one of the most important attributes of the ecolodge. | |

| Contribution of ecolodges in sustainable development | Hunta, Durham, Driscoll and Honey [95] | Investigating the contribution of ecotourism in local sustainable development | Interviews with 128 local residents, incl. 70 ecolodge employees, Costa Rica’s Osa, Peninsula | Quantitative analysis/qualitative coding by thematic content | Ecotourism had most important contribution in improvements of residents’ quality of life amongst locally available economic sectors. |

| Keough [96] | Exploring compliance of the Wenhai ecolodge with the principles of ecotourism | N/A | Case study | The compliance of the ecolodge with the principles of ecotourism was confirmed. | |

| Little and Blau [97] | Exploring multifaceted benefits and effects of agritourism | 21 stakeholders in the four eco-lodges, Mastatal, Costa Rica | Mixed method approach | Agritourism was an effective adaptation strategy to climate change and economic stressors. | |

| Miscellaneous themes | Coghlan and Castley [98] | Identifying perceptions of private tourism ecolodge concessions by residents, regulars and locals | 314 domestic visitors of Kruger National Park, South Africa | Descriptive statistics and content analysis | Those who lived closer to the park were significantly more likely to have more experience and better knowledge of the concessions but were also less likely to support their existence than other respondents. |

| Gawad [99] | Presenting an example of a design studio pedagogical process for designing an ecolodge | Feedback from 210 students on overall learning experience of designing an ecolodge in 2 touristic locations in Egypt. | Descriptive statistics | The teaching process of students’ ecolodge projects may include other supplementary components including invited guest speakers, field trips and so on. |

References

- Sharpley, R. Tourism Development and the Environment: Beyond Sustainability? Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, K. ‘Towards Sustainability? Tourism in the Republic of Cyprus’. In Practising Responsible Touism: International Case Studies in Tourism Planning, Policy and Development; Harrison, L., Husbands, W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1996; pp. 58–79. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel & Tourism Council & Oliver Wyman. To Recovery & Beyond: The Future of Travel & Tourism in the Wake of COVID-19. 2002. Available online: https://wttc.org/Initiatives/To-Recovery-Beyond (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Ainley, S.; Smale, B. A profile of Canadian agritourists and the benefits they seek. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2010, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan, S.; Blackstock, K.; Hunter, C. Agritourism from the perspective of providers and visitors: A typology-based study. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmazyari, H.; Asadi, A.; Kalantari, K.; Joppe, M.; Rezvani, M.R. Predicting potential agritourism segments on the basis of combined approach: The case of Qazvin, Iran. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2018; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, B.; Tetik, N. A new trend in the hotel industry: Ecolodges. Studia Univ. Babes-Bolyai Geogr. 2013, 58, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, H. Towards an internationally recognized ecolodge certification. In Quality Assurance and Certification in Ecotourism; Black, R., Crabtree, A., Eds.; CABI: London, UK, 2007; pp. 415–434. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.; Khare, A. Understanding Success Factors for Ensuring Sustainability in Ecotourism Development in Southern Africa. J. Ecotourism 2005, 4, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. A framework for ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D. Institutional and policy support for tourism social entrepreneurship. In Social Entrepreneurship and Tourism: Philosophy and Practice; Sheldon, P.J., Daniele, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D.A. Ecotourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R. The Politics of Ecotourism and the Developing World. J. Ecotourism 2006, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.-H.; Shafer, S. Marketing Ecotourism through the Internet: An Evaluation of Selected Ecolodges in Latin America and the Caribbean. J. Ecotourism 2005, 4, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E.; Magole, L.I.; Kgathi, D.L. Prospects and Challenges for Tourism Certification in Botswana. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2011, 36, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D. An ‘ecotourist’s recent experience in Sri Lanka. J. Ecotourism 2013, 12, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osland, G.E.; Mackoy, R. Ecolodge Performance Goals and Evaluations. J. Ecotourism 2004, 3, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, H.C. Sustainability of small-scale ecotourism: The case of Niue, South Pacific. Curr. Issues Tour. 2002, 5, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Promoting Women’s Empowerment Through Involvement in Ecotourism: Experiences from the Third World. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A. Does ecotourism contribute to sustainable destination development, or is it just a marketing hoax? Analyzing twenty-five years contested journey of ecotourism through a meta-analysis of tourism journal publications. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 1047–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawliczek, M.; Mehta, H. Ecotourism in Madagascar: How a sleeping beauty is finally awakening. In Responsible Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Arze, M.; Holladay, P.J. Overcoming externalities: Towards best ecotourism business practices in the Yacuma River Protected Area, Bolivia. J. Ecotourism 2017, 16, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coria, J.; Calfucura, E. Ecotourism and the development of indigenous communities: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 73, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. Neo-colonialism and greed: Africans’ views on trophy hunting in social media. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pêgas, F.D.V.; Stronza, A. Ecotourism equations: Do economic benefits equal conservation? Ecotourism Conserv. Am. 2009, 7, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L. Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, J. Addressing the social impacts of conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, J.-H. Evaluating ecotourism sustainability from the integrated perspective of resource, community and tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H. Citizen Participation in Urban Planning and Management, the Case of Iran, Shiraz City, Saadi Community; Kassel University Press: Kassel, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, M.E. Ecotourism: Principles, Practices and Policies for Sustainability; United Nations Publication: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, D.; Epler Wood, M.; Bittman, S. The Ecolodge Source book for Planners and Developers; The Ecotourism Society: North Bennington, VT, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos-Lascurain, H. Ecotourism and ecolodge development in the 21st century. In Ecotourism and Conservation in the Americas; Stronza, A., Durham, W.H., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blangy, S.; Mehta, H. Ecotourism and ecological restoration. J. Nat. Conserv. 2006, 14, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordkipanidze, M.; Brezet, H.; Backman, M. The entrepreneurship factor in sustainable tourism development. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP; WTO; FEEE. Awards for Improving the Coastal Environment: The Example of the Blue Flag; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ainley, S.; Kline, C. Moving beyond positivism: Reflexive collaboration in understanding agritourism across North American boundaries. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan Lian, K.J.; Baum, T. Motivation factors of ecotourists in ecolodge accommodation: The push and pull factors. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 12, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S.; Reichel, A. The cumulative nature of the entrepreneurial process: The contribution of human capital, planning and environment resources to small venture performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, S. Regional environment of destination and the entrepreneurship of small tourism businesses: A case study of Dali and Lijiang of Yunnan province. J. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Kim, K.; Jennings, G.R. Gender and motivation for agri-tourism entrepreneurship. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Liu, Y.; Ju, F.; Li, X. A Study on Farmers’ Agriculture related Tourism Entrepreneurship Behavior. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 122, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ritchie, J.B.; Echtner, C.M. Social capital and tourism entrepreneurship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1570–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C. A comparison of agritourism and other farm entrepreneurs: Implications for future tourism and sociological research on agritourism. In Proceedings of the 2008 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium, Bolton Landing, NY, USA, 30 March–1 April 2009; pp. 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, C. An importance-performance analysis of the motivations behind agritourism and other farm enterprise developments in Canada. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2010, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, N.P.; Black, R.J.; McCool, S.F. Agritourism: Motivations behind Farm/Ranch Business Diversification. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollenburg, C.; Buckley, R. Stated Economic and Social Motivations of Farm Tourism Operators. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, C.; Sharpley, R. Exploring Agritourism Entrepreneurship in the UK. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2011, 8, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Set, K.; Azizul, Y.Y.; Noor, Z.I.H.; Zatul, I.H. Understanding Motivation Factors of Tourism Entrepreneurs in Tasik Kenyir. Int. Acad. Res. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 1, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Amanor-Boadu, V. Diversification decisions in agriculture: The case of agritourism in Kansas. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Moraru, R.A.; Ungureanu, G.; Bodescu, D.; Donosă, D. Motivations and challenges for entrepreneurs in agritourism. Agron. Ser. Sci. Res. /Lucr. Stiintifice Ser. Agron. 2016, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Jabeen, F.; Khan, M. Entrepreneurs choice in business venture: Motivations for choosing home-stay accommodation businesses in Peninsular Malaysia. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Farrell, H. Tourism entrepreneurs in Northumberland. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1474–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chell, E.; Pittaway, L. A study of entrepreneurship in the restaurant and café industry: Exploratory work using the critical incident technique as a methodology. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1998, 17, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Silva, G.M.; Patuleia, M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Developing sustainable business models: Local knowledge acquisition and tourism lifestyle entrepreneurship. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Okumus, F.; Wu, K.; Köseoglu, M.A. The entrepreneurship research in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Petersen, T. Growth and profit-oriented entrepreneurship among family business owners in the tourism and hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, M.; Corsale, A. Rural tourism and livelihood strategies in Romania. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skokic, V.; Morrison, A. Conceptions of Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship: Transition Economy Context. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2011, 8, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlback, M. Strategic Entrepreneurship in the Hotel Industry: The Role of Chain Affiliation. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 12, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Characteristics and goals of family and owner-operated businesses in the rural tourism and hospitality sectors. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janet, C.; Simon, T.; Chen-Tsang, S.T.; Yi-Hui, C. Motivations and management objectives for operating micro-businesses in aboriginal communities. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2824–2835. [Google Scholar]

- Lashley, C.; Rowson, B. Lifestyle businesses: Insights into Blackpool’s hotel sector. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Reidy, C.A.; Dynesius, M.; Revenga, C. Fragmentation and flow regulation of the world’s large river systems. Science 2005, 15, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A.M. From Lifestyle Consumption to Lifestyle Production: Changing Patterns of Tourism Entrepreneurship. In Small Firms in Tourism; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snepenger, D.J.; Johnson, J.D.; Rasker, R. Travel-stimulated entrepreneurial migration. J. Travel Res. 1995, 34, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaugeois, N.; Rick, R. Mobility into tourism refuge employer? Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kennelly, J.J. Sustainability and Place-Based Enterprise. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, A.; Charmaz, K. Grounded Theory Methods for Mental Health Practitioners. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; Harper, D., Thompson, A.R., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Center of Iran. Number of Overnight Trips by Provinces Visited (Revised); National Visitor Survey Results; Statistical Center of Iran: Teheran, Iran, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in Methodology of Grounded Theory; Sociological Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McGehee, N.G.; Kim, K. Motivation for Agri-Tourism Entrepreneurship. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Toward a sociology of international tourism. Soc. Res. 1972, 39, 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D.; Markwell, K. Ethical and sustainability dimensions of foodservice in Australian ecotourism businesses. J. Ecotourism 2015, 2, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Death by a thousand cuts: Governance and environmental trade-offs in ecotourism development at Kangaroo Island, South Australia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, J.; Ramsaran, R.R. An exploratory examination of service quality attributes in the ecotourism industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 2, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, N. The third criterion of ecotourism: Are ecotourists more concerned about sustainability than other tourists? J. Ecotourism 2011, 1, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brochado, A.; Pereira, C. Comfortable experiences in nature accommodation: Perceived service quality in Glamping. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 1, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan Lian, K.J.; Baum, T. Ecotourists’ perception of ecotourism experience in lower Kinabatangan, Sabah, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 10, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, P.; Eagles, P.F.; Gebhardt, A. A comparison of ecolodge patrons’ characteristics and motivations based on price levels: A case study of Belize. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 6, 698–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, P.; Eagles, P.F.; Gebhardt, A. Ecolodge patrons’ characteristics and motivations: A study of Belize. J. Ecotourism 2010, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, L.J. A profile of older adult ecotourists in Australia. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2002, 9, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. Ecotourism experiences reported online: Classification of satisfaction attributes. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, M.; Pratt, S.; Trupp, A. Determining ecotourism satisfaction attributes–a case study of an ecolodge in Fiji. J. Ecotourism 2020, 19, 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Rodger, K.; Pearce, J.; Chan, K.L. Visitor satisfaction with a key wildlife tourism destination within the context of a damaged landscape. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.D.; Sumanapala, D.P.; Galahitiyawe, N.W.; Newsome, D.; Perera, P. Exploring motivation, satisfaction and revisit intention of ecolodge visitors. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 26, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. Overnight ecotourist market segmentation in the Gold Coast hinterland of Australia. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Hard-core ecotourists in Lamington National park, Australia. J. Ecotourism 2002, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grosbois, D.; Fennell, D.A. Sustainability and ecotourism principles adoption by leading ecolodges: Learning from best practices. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Luo, J.M.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Henriques, D. Qualitative study of green resort attributes--A case of the crosswaters resort in China. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1742525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mic, M.; Eagles, P.F. Cooperative branding for mid-range ecolodges: Costa Rica case study. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 25, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Dominguez, E.; Argudo-Guevara, N.; Arce-Bastidas, R. Social listening: Análisis de contenido generado por los turistas en TripAdvisor acerca del ecolodge Napo Wild Life Center, Ecuador. Rev. Espacios 2018, 39, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, C.A.; Durham, W.H.; Driscoll, L.; Honey, M. Can ecotourism deliver real economic, social, and environmental benefits? A study of the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keough, S.B. The wenhai ecolodge: A case study of culture and environment in southwest China. FOCUS Geogr. 2010, 53, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, M.E.; Blau, E. Social adaptation and climate mitigation through agrotourism: A case study of tourism in Mastatal, Costa Rica. J. Ecotourism 2020, 19, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Castley, J.G. A matter of perspective: Residents’, regulars’ and locals’ perceptions of private tourism ecolodge concessions in Kruger National Park, South Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gawad, I.O. Ecolodge Design and Architectural Education: A New approach for Design Studios. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 3877–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Name | Logo | Countries | Year | Managing Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ECO certification |  | Malta | 2002 | Malta Tourism Authority |

| 2 | EcoLabel Luxembourg |  | Luxembourg | 1999 | Oekozenter Pafendall |

| 3 | Green Certificate |  | Latvia | 2001 | Latvian Country Tourism association |

| 4 | Green Tourism Business Scheme |  | Canada, Ireland, United Kingdom | 1997 | Green Business UK Ltd. |

| 5 | ibex fairstay |  | Switzerland | 2002 | ibex fairstay |

| 6 | International Eco Certification Program |  | Australia | 1991 | Ecotourism Australia |

| 7 | Legambiente Turismo |  | Italy | 1997 | Legambiente Turismo |

| 8 | Nature’s Best Ecotourism |  | Sweden | 2002 | Swedish Ecotourism Society |

| 9 | Sustainable Tourism Education Program (STEP) |  | Ireland, Malawi, Mexico, United Kingdom, United States | 2007 | Sustainable Travel International |

| 10 | Viabono |  | Germany | N/A | Viabono |

| 11 | Estonian Ecotourism Quality Label |  | Estonia | N/A | Estonian Ecotourism Association |

| 12 | Calidad Galapagos |  | Ecuador | N/A | Capturgal |

| 13 | Green Key |  | Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, France, Greece, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Latvia, Lithuania, Morocco, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Russian Federation, Sweden, Tunisia, Ukraine | 1994 | Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varmazyari, H.; Mirhadi, S.H.; Joppe, M.; Kalantari, K.; Decrop, A. Ecolodge Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets: A New Typology of Entrepreneurs; The Case of IRAN. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148479

Varmazyari H, Mirhadi SH, Joppe M, Kalantari K, Decrop A. Ecolodge Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets: A New Typology of Entrepreneurs; The Case of IRAN. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148479

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarmazyari, Hojjat, Seyed Hamid Mirhadi, Marion Joppe, Khalil Kalantari, and Alain Decrop. 2022. "Ecolodge Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets: A New Typology of Entrepreneurs; The Case of IRAN" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148479

APA StyleVarmazyari, H., Mirhadi, S. H., Joppe, M., Kalantari, K., & Decrop, A. (2022). Ecolodge Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets: A New Typology of Entrepreneurs; The Case of IRAN. Sustainability, 14(14), 8479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148479