Incorporating Fuzzy Cognitive Inference for Vaccine Hesitancy Measuring

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Designing a double-weighted group decision-making strategy to measure nonlinear correlations among factors of vaccine hesitancy determinants. Eight experts from three professions (hospital, government, and academia) are invited to finish the determinants matrix composed of the edges between a pair of factors. Features of edges include information of sign, weight, and certainty of their decision. Two weights are considered in integrating the decisions. The first level of weight concerns the relationship strength decided by each expert, and the second level of weight concerns the certainty degree of each decision. This strategy ensures an independent and efficient group decision-making process.

- (2)

- Inferring the state transition and interactive processes of factors through the fuzzy cognitive map. In the process, the fuzzy number is used to describe the fuzzy language of experts, with the trapezoidal fuzzy number of edge weights and the triangular fuzzy number of the certainties. Finally, a decision matrix with 24 × 24 dimensions is built to serve as the adjacent matrix of the fuzzy cognitive map.

- (3)

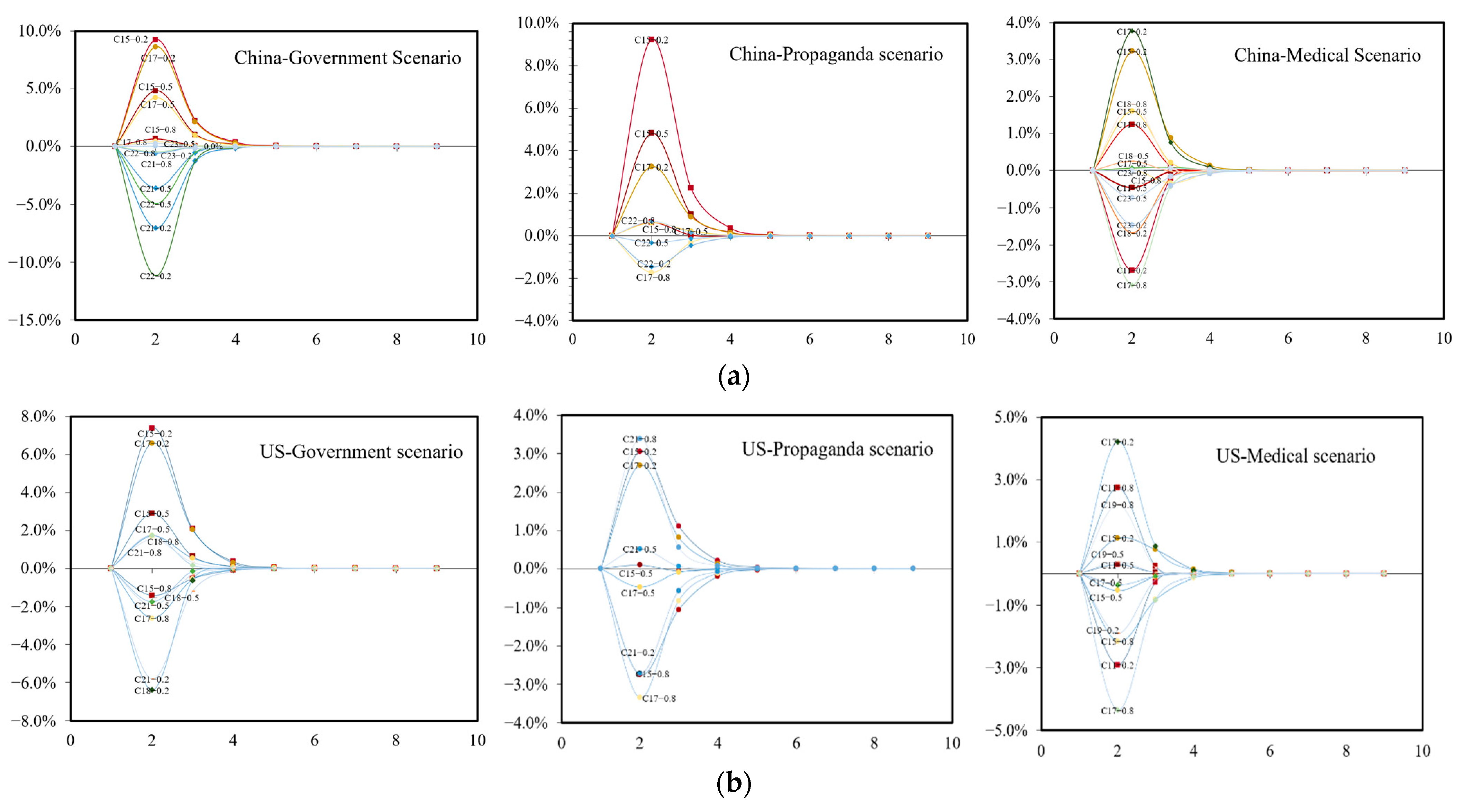

- Three scenarios are designed to simulate government, propaganda, and medical scenarios. Simulation results help identify the sensitive factors under different scenarios that need extra attention. An application case is conducted to demonstrate how the system can work in reality.

2. Related Work

2.1. Vaccine Hesitancy

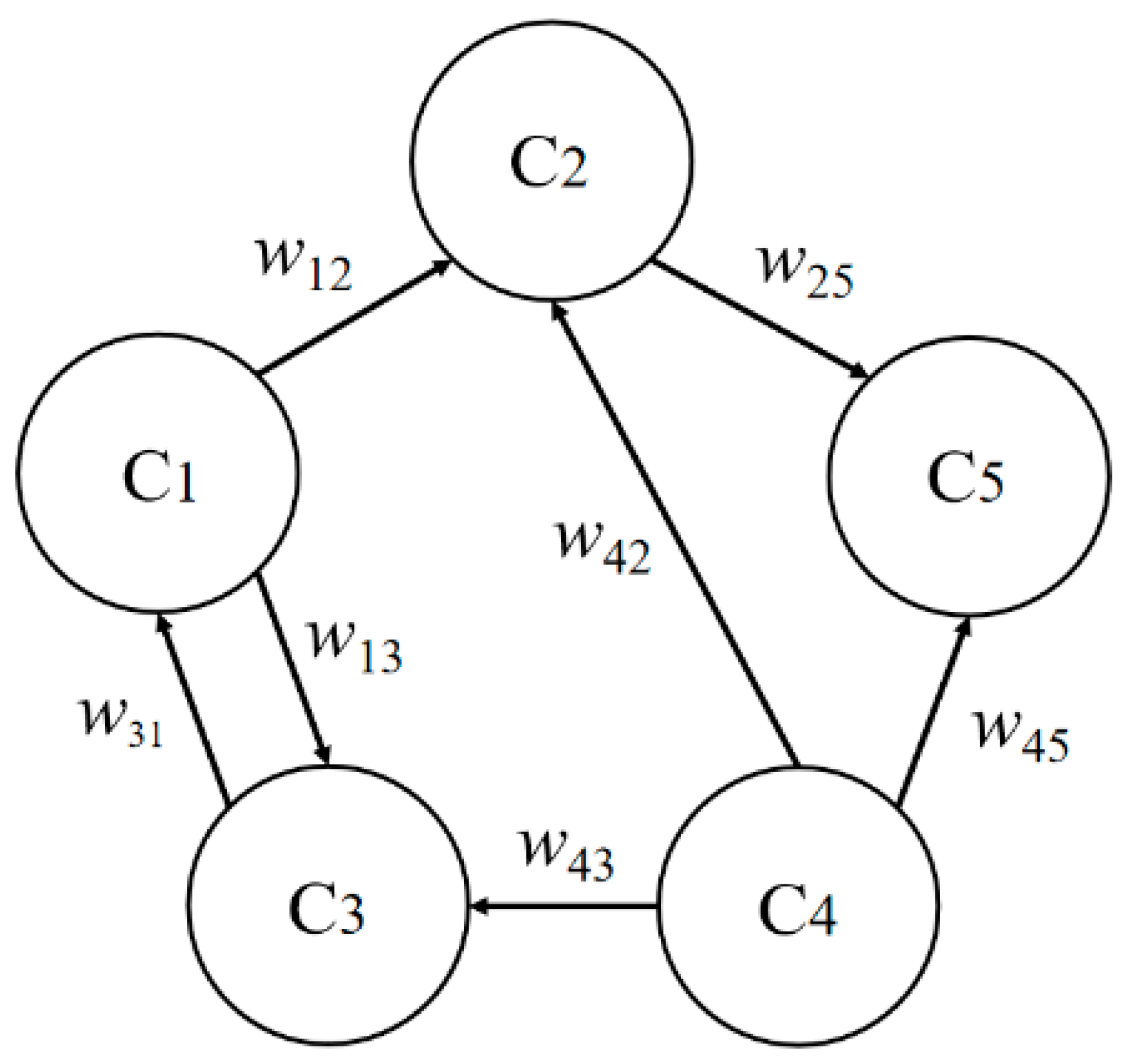

2.2. Fuzzy Cognitive Inference

3. Data and Method

3.1. Fuzzy Cognitive Map of Vaccine Hesitancy

3.2. Model Building

4. Result

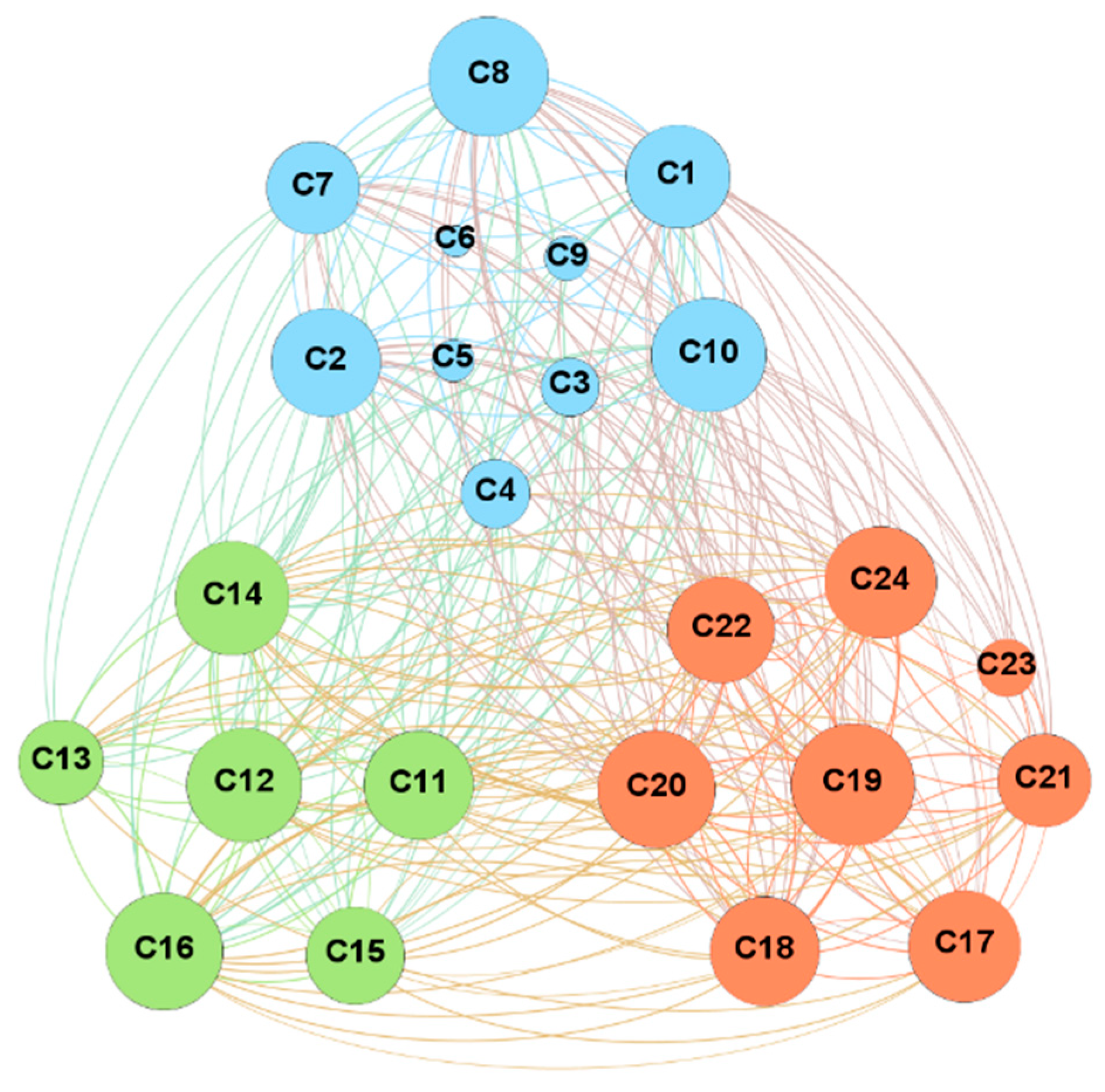

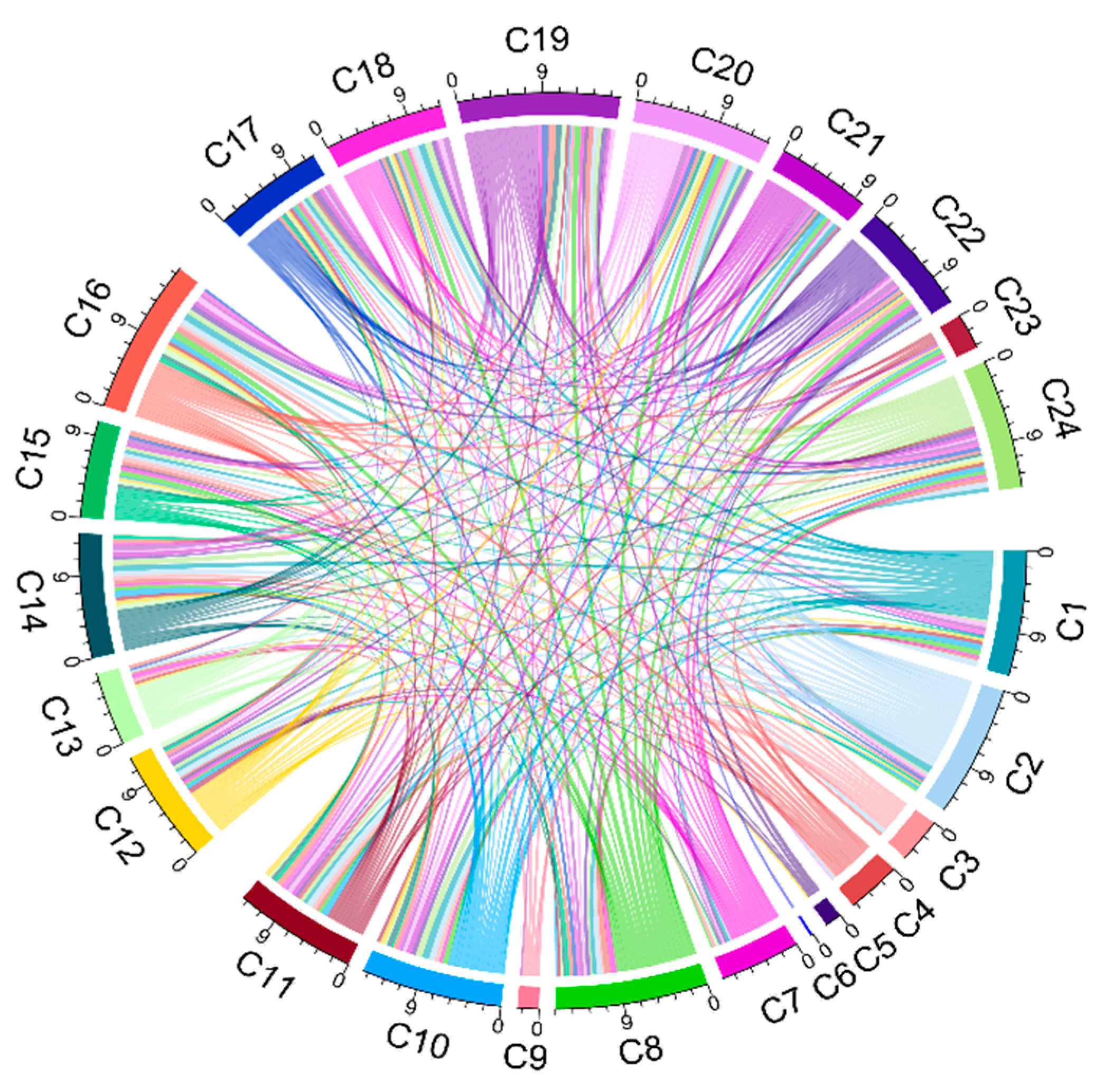

4.1. Network Analysis

- (1)

- Degree analysis. C19 (mode of administration) and C8 (politics/policies) are the top two nodes with the highest degree value, both of which are macro-factors with obvious social and political attributes. In contrast, nodes with smaller degree values have obvious personal and environmental attributes, including C6 (gender structure), C5 (age structure), and C9 (geographic barriers), indicating that these factors are not easily influenced by the nodes in the network.

- (2)

- Out-degree analysis. Remarkably, that the outdegree of the nodes C2 (opinion leaders), C19 (mode of administration), C8 (politics/policies), C1 (communication and media environment), and C7 (socio-economic) occupies more than 50% of their degrees in total. These factors strongly correlate with other factors in the network and a stronger ability to influence others.

- (3)

- In-degree analysis. The node with the highest in-degree value is C17 (realistic level risk-return ratio), followed by C14 (trust in the healthcare system), C16 (social norm perception), C20 (level of mobilization for vaccination), and C24 (the strength of medical staff’s recommendation). The in-degree of these nodes exceeds 50% of the degree value, illustrating that the public perception of the risks of vaccination, social perception, and trust in the medical system will be influenced by multiple factors.

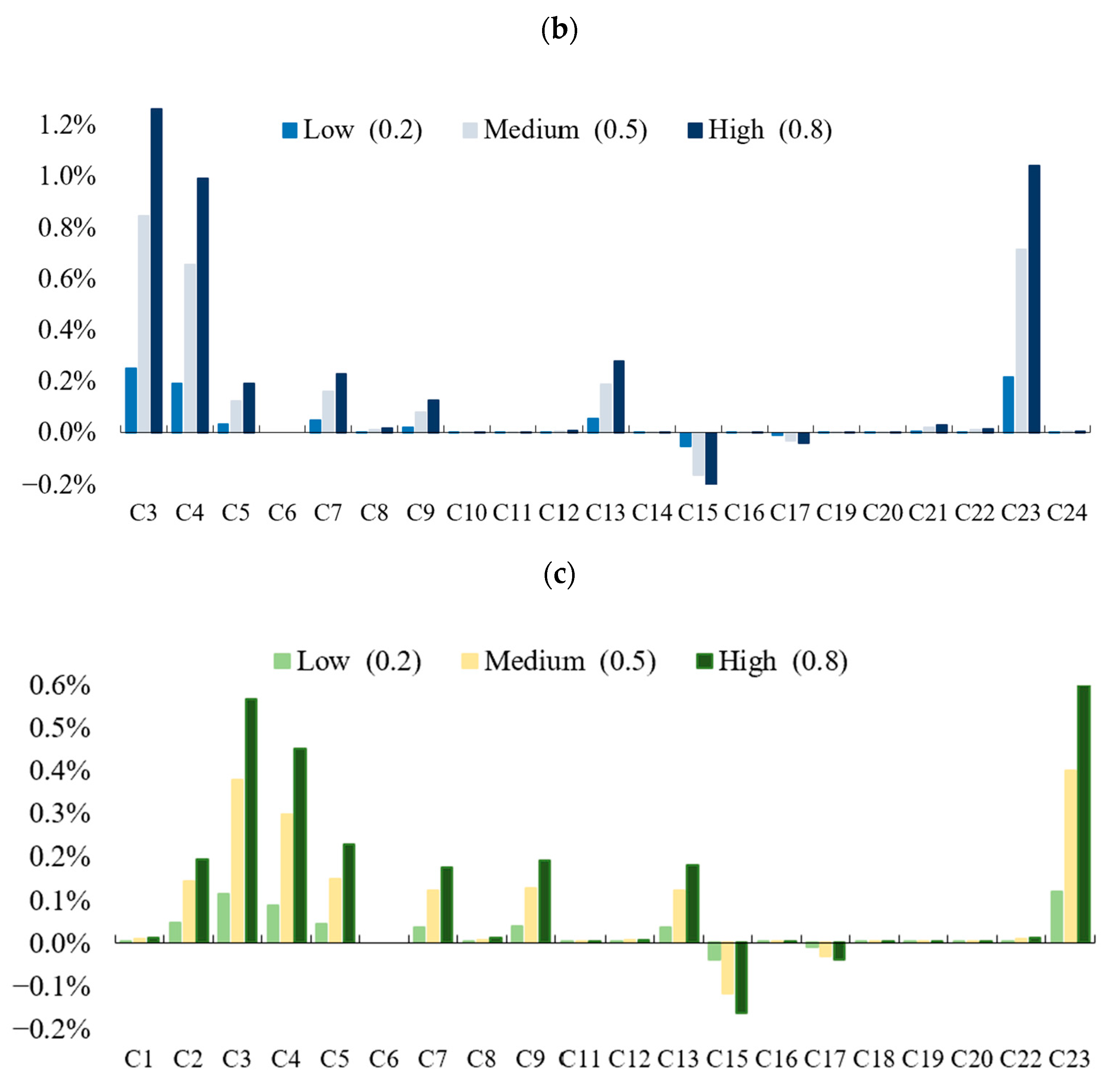

4.2. Simulations on Three Scenarios

4.3. Experiment Result Analysis

- (1)

- Government scenario

- (2)

- Propaganda scenario

- (3)

- Medical scenario

5. Application Case

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Randolph, H.E.; Barreiro, L.B. Herd immunity: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 2020, 52, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D. Instructing durable humoral immunity for COVID-19 and other vaccinable diseases. Immunity 2022, 55, 945–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Mateus, J.; Coelho, C.H.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Gálvez, R.I.; Cortes, F.H.; Grifoni, A.; Tarke, A.; Chang, J.; et al. Humoral and cellular immune memory to four COVID-19 vaccines. Cell, 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A.; Anderson, E.J.; Rouphael, N.G.; Roberts, P.C.; Makhene, M.; Coler, R.N.; McCullough, M.P.; Chappell, J.D.; Denison, M.R.; Stevens, L.J.; et al. An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—Preliminary Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, A.B.; Kanevsky, I.; Che, Y.; Swanson, K.A.; Muik, A.; Vormehr, M.; Kranz, L.M.; Walzer, K.C.; Hein, S.; Güler, A.; et al. BNT162b vaccines protect rhesus macaques from SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 592, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoff, J.; Gray, G.; Vandebosch, A.; Cárdenas, V.; Shukarev, G.; Grinsztejn, B.; Goepfert, P.A.; Truyers, C.; Fennema, H.; Spiessens, B.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2187–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T.K. Omicron variant and booster COVID-19 vaccines. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhade, C.; Zou, J.; Xia, H.; Cai, H.; Yang, Q.; Cutler, M.; Cooper, D.; Muik, A.; Jansen, K.U.; Xie, X.; et al. Neutralization of Omicron BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3 SARS-CoV-2 by 3 doses of BNT162b2 vaccine. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejnirattisai, W.; Huo, J.; Zhou, D.; Zahradník, J.; Supasa, P.; Liu, C.; Duyvesteyn, H.M.; Ginn, H.M.; Mentzer, A.J.; Tuekprakhon, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-B.1.1.529 leads to widespread escape from neutralizing antibody responses. Cell 2022, 185, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, C.I.; Bergeron, A.J.; Ahlm, C.; Normark, J.; Sakharkar, M.; Forsell, M.N.E.; Walker, L.M. Recall of pre-existing cross-reactive B cell memory following Omicron BA.1 breakthrough infection. Sci. Immunol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M.; Hasell, J.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Rodés-Guirao, L. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.C.S.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Huang, J.; Lai, C.K.C.; Yeoh, E.K.; Chan, P.K.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a City with Free Choice and Sufficient Doses. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Mercade, P.; Meier, A.N.; Schneider, F.H.; Meier, S.; Pope, D.; Wengström, E. Monetary incentives increase COVID-19 vaccinations. Science (1979) 2021, 374, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, P.; Brunton-Smith, I.; Jackson, J. Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergur, A. Social causes of vaccine rejection-vaccine indecision attitudes in the context of criticisms of modernity. Eurasian J. Med. 2020, 52, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.K.; Zhao, T.-F.; Chen, W.-N.; Zhang, J. Toward predicting active participants in tweet streams: A case study on two civil rights events. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Failla, G.; Ricciardi, W. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 40, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonsenso, D.; Valentini, P.; Macchi, M.; Folino, F.; Pensabene, C.; Patria, M.F.; Agostoni, C.; Castaldi, S.; Lecce, M.; Lorella, M.; et al. Caregivers’ Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Vaccination in Children and Adolescents with a History of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 7, 867968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagateli, L.E.; Saeki, E.Y.; Fadda, M.; Agostoni, C.; Marchisio, P.; Milani, G.P. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Parents of Children and Adolescents Living in Brazil. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.E.; Carter, B. Parental preferences for a mandatory vaccination scheme in England: A discrete choice experiment. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 16, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, S.; MacDonald, N.E.; Guirguis, S. Health communication and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4212–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Friedrich, M.J. WHO’s top health threats for 2019. JAMA 2019, 321, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.E.; Saad-Roy, C.M.; Morris, S.E.; Baker, R.E.; Mina, M.J.; Farrar, J.; Holmes, E.C.; Pybus, O.G.; Graham, A.L.; Emanuel, E.J.; et al. Vaccine nationalism and the dynamics and control of SARS-CoV-2. Medrxiv 2021, 373, 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzezinski, A.; Kecht, V.; van Dijcke, D.; Wright, A.L. Science skepticism reduced compliance with COVID-19 shelter-in-place policies in the United States. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwell, K.; Smith, D.T. Parenting as politics: Social identity theory and vaccine hesitant communities. Int. J. Health Gov. 2017, 22, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoš, V.; Bauer, M.; Cahlíková, J.; Chytilová, J. Communicating doctors’ consensus persistently increases COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature 2022, 606, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, A.; Larson, H.J. Exploratory study of the global intent to accept COVID-19 vaccinations. Commun. Med. 2021, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, N.E.; Clemente, L.; Liautaud, P.; Kaashoek, J.; Link, N.B.; Nguyen, A.T.; Lu, F.S.; Huybers, P.; Resch, B.; Havas, C.; et al. An early warning approach to monitor COVID-19 activity with multiple digital traces in near real time. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Litvinova, M.; Liang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Shi, H.; Vespignani, A.; Viboud, C.; Ajelli, M.; Yu, H. The impact of relaxing interventions on human contact patterns and SARS-CoV-2 transmission in China. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, M.; Blenkinsop, A.; Xi, X.; Hebert, D.; Bershan, S.; Tietze, S.; Baguelin, M.; Bradley, V.C.; Chen, Y.; Coupland, H.; et al. Age groups that sustain resurging COVID-19 epidemics in the United States. Science (1979) 2021, 371, eabe8372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevik, M.; Marcus, J.L.; Buckee, C.; Smith, T.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission dynamics should inform policy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, S170–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, E.; Gagnon, D.; MacDonald, N.; Bocquier, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Verger, P. Underlying factors impacting vaccine hesitancy in high income countries: A review of qualitative studies. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2018, 17, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.-K.; Zhao, T.-F.; Lu, L.; Chen, W.-N. Predicting the Hate: A GSTM Model based on COVID-19 Hate Speech Datasets. Inf. Processing Manag. 2022, 59, 102998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.-F.; Chen, W.-N.; Kwong, S.; Gu, T.-L.; Yuan, H.-Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Evolutionary divide-and-conquer algorithm for virus spreading control over networks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 51, 3752–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.-F.; Chen, W.-N.; Liew, A.W.-C.; Gu, T.; Wu, X.-K.; Zhang, J. A binary particle swarm optimizer with priority planning and hierarchical learning for networked epidemic control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 51, 5090–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onari, M.A.; Yousefi, S.; Rabieepour, M.; Alizadeh, A.; Rezaee, M.J. A medical decision support system for predicting the severity level of COVID-19. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 7, 2037–72051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, F.J.; Bor, A.; Petersen, M.B. Compliance without fear: Individual-level protective behaviour during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S.; Govindan, K.; Broumi, S. Analysis of Covid-19 via Fuzzy Cognitive Maps and Neutrosophic Cognitive Maps. Neutrosophic Sets Syst. 2021, 42, 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.E.; Canning, D.; Sevilla, J. The effect of health on economic growth: A production function approach. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkow, A.; Zaleskiewicz, T.; Petrova, D.; Garcia-Retamero, R.; Traczyk, J. Worry, risk perception, and controllability predict intentions toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groumpos, P.P. Why Modelling the COVID-19 pandemic using Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCM)? IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groumpos, P. Modelling COVID-19 using Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCM). EAI Endorsed Trans. Bioeng. Bioinform. 2021, 1, 168728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhani, A.; Kolahdoozi, M.; Wang, C.; Kurgan, L.A. Prediction of DNA-binding residues in local segments of protein sequences with Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2018, 17, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakostas, G.A.; Boutalis, Y.S.; Koulouriotis, D.E.; Mertzios, B.G. Fuzzy cognitive maps for pattern recognition applications. Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 2008, 22, 1461–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, K.; Suresh, S.; Sundararajan, N. A metacognitive neuro-fuzzy inference system (McFIS) for sequential classification problems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2013, 21, 1080–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhani, A.; Papageorgiou, E.I.; Mohseni, A.; Mosavi, M.R. A review of fuzzy cognitive maps in medicine: Taxonomy, methods, and applications. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2017, 142, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, V.C.; Malandraki, G.A.; Stylios, C.D. A fuzzy cognitive map approach to differential diagnosis of specific language impairment. Artif. Intell. Med. 2003, 29, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosko, B. Fuzzy systems as universal approximators. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1994, 43, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Liu, Z.-Q. On Causal Inference in Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2000, 8, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhe, G. Hybrid intelligence in software release planning. Int. J. Hybrid Intell. Syst. 2004, 1, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vena-Oya, J.; García-Castañeda, J.A.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.Á. Forecasting a post-COVID-19 economic crisis using fuzzy cognitive maps: A Spanish tourism-sector perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamakan, S.M.H.; Malekinejad, P.; Ziaeian, M.; Motavali, A. Bullwhip effect reduction map for COVID-19 vaccine supply chain. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2021, 2, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, V.F.; Broniatowski, D.A.; Edelson, S.M. Viruses, Vaccines, and COVID-19: Explaining and Improving Risky Decision-making. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2021, 10, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, G.; Nápoles, G.; Falcon, R.; Froelich, W.; Vanhoof, K.; Bello, R. A review on methods and software for fuzzy cognitive maps. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 1707–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosko, B. Fuzzy cognitive maps. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1986, 24, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, E.I.; Salmeron, J.L. A review of fuzzy cognitive maps research during the last decade. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2013, 21, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Logic. Computer 1988, 21, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toan, T.D.; Wong, Y.D. Fuzzy logic-based methodology for quantification of traffic congestion. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 570, 125784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-M.; Liu, L.; Sun, J.; Yan, W.; Yuan, K.; Zheng, Y.-B.; Lu, Z.-A.; Liu, L.; Ni, S.-Y.; Su, S.-Z.; et al. Public willingness and determinants of COVID-19 vaccination at the initial stage of mass vaccination in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; He, Z.; Huang, J.; Yan, N.; Chen, Q.; Huang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Akinwunmi, O.; Akinwunmi, B.; Zhang, C.; et al. A comparison of vaccine hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccination in China and the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, B.; Jha, R.M. Soft Computing Techniques. In Soft Computing in Electromagnetics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, V.; Perfilieva, I.; Močkoř, J. Mathematical Principles of Fuzzy Logic; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkman, J.G.; van Haeringen, H.; de Lange, S.J. Fuzzy Numbers. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1983, 92, 301–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Factors |

|---|

| Contextual factors |

| C1 Communication and media environment |

| C2 Opinion leader |

| C3 Historical influences |

| C4 Religion/culture |

| C5 Age structure |

| C6 Gender structure |

| C7 Socio-economic |

| C8 Politics/policies |

| C9 Geographic barriers |

| C10 Perception of the pharmaceutical industry |

| Individual and group factors |

| C11 Vaccine experience |

| C12 Healthy attitude |

| C13 Education level |

| C14 Trust in the healthcare system |

| C15 Risk–benefit ratio at cognitive level |

| C16 Social norms perception |

| Vaccine and vaccination factors |

| C17 Risk–benefit ratio at realistic level |

| C18 Popularity of vaccine science |

| C19 Mode of administration |

| C20 Level of mobilization for vaccination |

| C21 Reliability of vaccination |

| C22 Vaccination planning |

| C23 Vaccination costs |

| C24 The strength of the medical staff’s recommendation |

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Node | 24 |

| Edge | 292 |

| Network diameter | 4 |

| Network density | 0.529 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.663 |

| Average path length | 1.514 |

| Node | Degree | Node | In-Degree | Node | Out-Degree | Node | Betweenness Centrality | Node | Closeness Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C19 | 335 | C17 | 19 | C2 | 20 | C19 | 42.72 | C6 | 0.42 |

| C8 | 34 | C16 | 18 | C19 | 18 | C12 | 35.42 | C23 | 0.49 |

| C16 | 33 | C20 | 18 | C8 | 17 | C2 | 30.71 | C5 | 0.52 |

| C20 | 33 | C14 | 18 | C1 | 15 | C22 | 30.51 | C9 | 0.52 |

| C14 | 32 | C24 | 18 | C7 | 15 | C20 | 23.54 | C3 | 0.59 |

| Factors | Parameters |

|---|---|

| C1 Communication and media environment | 0.575 |

| C2 Opinion leader | 0.65 |

| C3 Historical influences | 0.2 |

| C4 Religion/culture | 0.365 |

| C5 Age structure | 0.95 |

| C6 Gender structure | 0.45 |

| C7 Socio-economic | 0.605 |

| C8 Politics/policies | 0.75 |

| C9 Geographic barriers | 0.1 |

| C10 Perception of the pharmaceutical industry | 0.65 |

| C11 Vaccine experience | 0.8 |

| C12 Healthy attitude | 0.655 |

| C13 Education level | 0.5 |

| C14 Trust in the healthcare system | 0.44 |

| C15 Risk–reward ratio at the cognitive level | 0.645 |

| C16 Social norm perception | 0.225 |

| C17 Realistic level risk–return ratio | 0.155 |

| C18 Popularity of vaccine science | 0.25 |

| C19 Mode of administration | 0.8 |

| C20 Level of mobilization for vaccination | 0.605 |

| C21 Reliability of vaccination | 0.505 |

| C22 Vaccination planning | 0.7 |

| C23 Vaccination costs | 0.295 |

| C24 The strength of the medical staff’s recommendation | 0.4 |

| Soft computing | A set of computing techniques based on artificial intelligence (human-like decision making) and natural selection [64]. |

| Fuzzy logic | A form of many-valued logic in which the truth value of variables may be any real number between [0, 1] or [−1, +1] [65]. |

| Fuzzy numbers | A fuzzy number is a generalization of a regular, real number in the sense that it does not refer to one single value, but rather to a connected set of possible values, where each possible value has its own weight between 0 and 1 [66]. |

| Fuzzy cognitive mapping (FCM) | A map-based knowledge representation method, with nodes representing concepts, and edges representing causal relationships among concepts [58]. |

| Vaccine hesitancy | The delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine service [18]. |

| Group decision making | A method to achieve more effective and optimized solutions by integrating the opinions of committees, teams, small groups, partnerships, or other collaborative social processes. |

| Contextual factors | The factors influencing vaccine hesitancy [18]. |

| Individual and group factors | The influence of individual, group, social, peer environment, and other factors on vaccine hesitancy [18]. |

| Vaccine and vaccination Factors | Factors directly related to vaccines or directly related to vaccination [18]. |

| Vaccine hesitancy determinants matrix | A matrix describing the crucial factors in vaccine hesitancy conceptually, proposed by the WHO SAGE Working Group [18]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, K.; Zhao, T.-F.; Wu, X.-K.; Lai, K.-S.; Chen, W.-N.; Zhang, J.-S. Incorporating Fuzzy Cognitive Inference for Vaccine Hesitancy Measuring. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148434

Sun K, Zhao T-F, Wu X-K, Lai K-S, Chen W-N, Zhang J-S. Incorporating Fuzzy Cognitive Inference for Vaccine Hesitancy Measuring. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148434

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Kun, Tian-Fang Zhao, Xiao-Kun Wu, Kai-Sheng Lai, Wei-Neng Chen, and Jin-Sheng Zhang. 2022. "Incorporating Fuzzy Cognitive Inference for Vaccine Hesitancy Measuring" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148434

APA StyleSun, K., Zhao, T.-F., Wu, X.-K., Lai, K.-S., Chen, W.-N., & Zhang, J.-S. (2022). Incorporating Fuzzy Cognitive Inference for Vaccine Hesitancy Measuring. Sustainability, 14(14), 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148434