1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Several recent cultural heritage conservation principles distinguish movable and real estate cultural heritage, but in principle not transport or move real estate heritage (

Appendix A. a1.). However, in some cases, the move of architectural heritage has been permitted in the principles of conservation of several cultural heritages of ICOMOS, which are for architectures or monuments. This has been the case since the relocation of Abu Simbel, Egypt, led by UNESCO in the 1960s. In addition, while these documents allow for the relocation of architectural heritage, it can be seen that the criteria for permitting vary from time to time.

“

The Burra Charter” (ICOMOS, 1979), “

The Appleton Charter” (ICOMOS, 1983), and “

New Zealand Charter” (ICOMOS, 1992) allowed as ‘

sole means of ensuring its survival’, ‘

a last resort, if protection cannot be achieved by any other means’, ‘

its current site is in imminent danger, and if all other means of retaining the structure in its current location have been exhausted’. After that, in “

The Burra Charter (revision)” (ICOMOS, 1999), in case of, ‘

Some buildings, works or other components of places were designed to be readily removable or already have a history of relocation. Provided such buildings, works or other components do not have significant links with their present location’, it is allowed to relocate [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

However, it is difficult to judge the criteria for ‘

a last resort’

and ‘

in imminent danger’, ‘

readily removable’,

and ‘

significant links with their present location’ in these principles because the standards are unclear. This also appears in Korean law. In Korea, as a principle directly referring to relocation, there is “

General Principles for Repair, Restoration and Management of Historic Buildings and Relics” (Cultural Heritage Administration in Korea, 2009). According to this, relocation of architectural heritages is permitted only in cases ‘

for protection’, ‘

for restoration to its original site’, and ‘

other unavoidable cases’ [

6]. The standard is ambiguous because there is no definition for ‘

other unavoidable cases’.

However, one thing is certain, that the relocation of architectural heritages does not always mean that the value of the heritage has been damaged or that its authenticity has been lost. In fact, many architectural heritages that were relocated in Korea, especially in Seoul, were not deprived of their cultural heritage status after that. In addition, a previous study emphasized that the authenticity of architectural heritages is not always related to the original site because the surrounding environment can change even though the structure has been conserved in its original site [

7].

1.2. The Aim and Meaning of the Study

As above, the criteria for permitting domestic and foreign relocation are unclear and inconsistent. The purpose of this study is to find out what standards actually allowed the relocation under these unclear standards. In addition, based on this, I would like to interpret where the conservation value of architectural heritage was placed.

In the category of Cultural Properties, the characteristic of only architectural heritages is that the ‘original site’ can be specified. The decision on whether to relocate architectural heritages is linked to the question of whether it is worth conserving in its original site. It can be seen that the relocation was approved in order to pursue a more important value than the value of the original site of the architectural heritage. This shows the perception of each period and subject for the conservation of architectural heritages. For example, “

The Venice Charter” (ICOMOS, 1964) permitted the relocation of architectural heritage for ‘

national or international interest of paramount importance’ [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This means that ‘

national and international interest’ were considered more valuable than the conservation of cultural heritage at the time.

1.3. Subject and Methods of the Study

Many of the traditional Korean architecture are wooden structures that do not use nails. Therefore, since it is easy to dismantle and reassemble, relocation has been frequently performed since ancient times for material reuse and cost reduction. However, in modern times, the concept of conservation of cultural properties was introduced and the dismantling and reassembly of architectural heritage was legally prohibited. In Korea, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act was first enacted in 1963, and, from then on, the relocation of architectural cultural properties was only possible with permission from the Cultural Heritage Administration (

Appendix A. a2.). Therefore, in this study, from 1963 to the present, architectural cultural properties legally relocated with permission from the Cultural Heritage Committee are taken as target cases. Regionally, only those relocated within Seoul, the capital of the Republic of Korea, are covered. In this study, the word ‘Cultural Property’ means only the heritage officially designated or registered as a subject of conservation under the Korean Cultural Heritage Protection Act. There may be several criteria for classifying whether or not it falls under ‘architecture’, but in this study, only ‘buildings’ that can contain human activities were considered ‘architecture’. Therefore, castles, towers, monuments, tombs, sites, historical sites, and relic distribution sites are excluded.

The first stage of the study is to investigate all cases of architectural cultural heritage relocated within Seoul. Based on the approval documents for permission to change the status quo at the time, the criteria for permitting moving in each case are determined. In addition, we find commonalities and differences between them, categorize them, and find and interpret their tendencies and characteristics. Through this, we find out what values of architectural heritage were prioritized at that time.

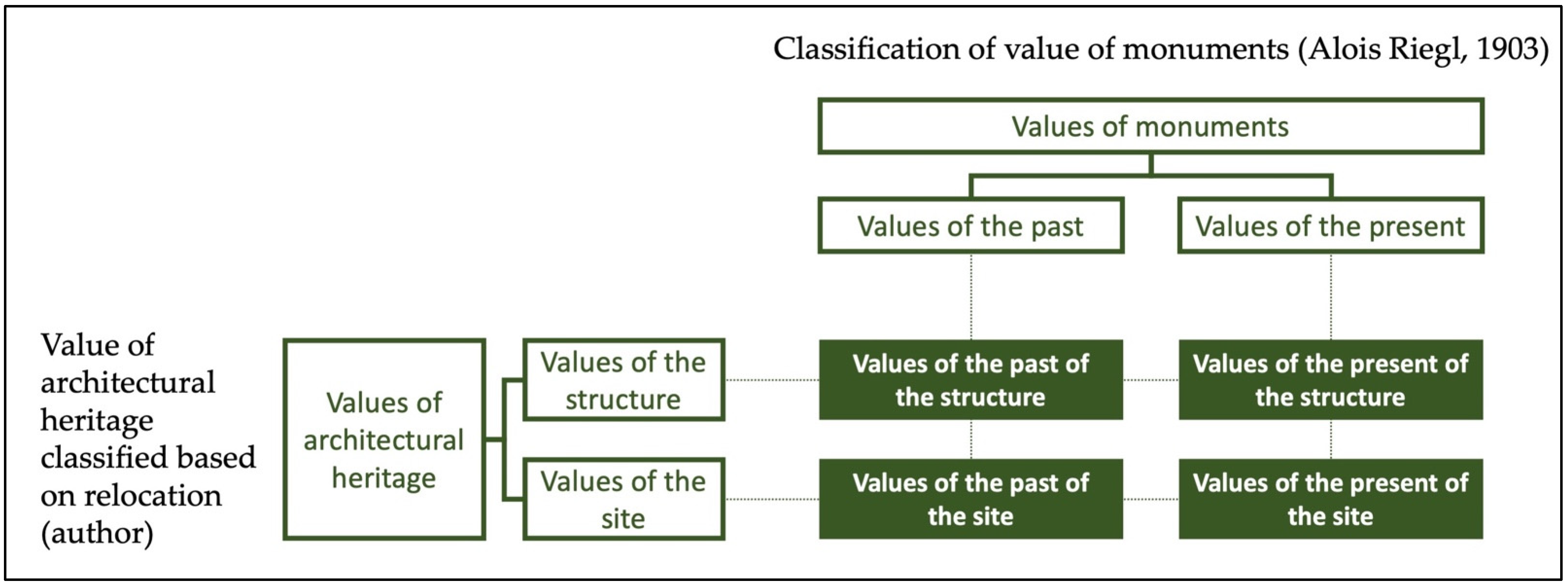

The second step is to explain the reasons why the relocation was permitted in each case based on the architectural heritage value system. The value of heritage can be classified in various ways, but in this study. Lipe (1984) classified

the values of Economic, Aesthetic, Associative-symbolic, and

Informational, and Frey (1997) classified them into

the values of Monetary, Option, Existence, Bequest, Prestige, and

Educational. Burra Charter (1998) classified

the values of Aesthetic, Historic, Scientific, and

Social, and English Heritage (1997) classified them as

Cultural, Educational and Academic, Economic, Resource, Recreational, and

Aesthetic values [

8]. However, most of these values appear overlapping each other. Therefore, in this study, the method of classifying into present value and past value among Alois Riegl’s classification of monument values (1903) was applied. This is because present values and past values are clearly distinguished. On the other hand, relocation is an act of separating the structure and the site of the architectural heritage. Therefore, the value of the structure and the value of the site were classified. These were applied to Alois Riegl’s and classified into four value systems—the ‘value of the structure’ and the ‘value of the site’, and it is divided into the ‘values of the past’ and the ‘values of the present’.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Prior Research and Case Study

Internationally, many studies on relocation have been conducted in Japan and the United States, and there have been many studies on how to relocation the whole thing without dismantling it—

Hikiya (曳家), moving buildings—unlike the case of Korea where it was dismantled and relocated [

9,

10,

11,

12]. ‘曳’ in ‘曳家’ means to drag, and ‘家’ means house, so it means to drag and move a house without dismantling it. On the other hand, among the studies related to open-air museums, there was a study dealing with the relocation that occurred during the construction process [

7,

13,

14]. However, since the subject of their research was not limited to ‘for the conservation’ or ‘national cultural property’, the analysis on the acceptance criteria for relocation is not valid. Japanese architect Keisuke Fujii said that relocation occurs when the social lifespan of a building is shorter than the physical lifespan. In ancient Japan, it was found that there were many relocations due to new town planning, dismantling of fortresses, separation of gods and Buddhists, and conversion of high-end houses to temples, etc. [

15]. After the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923) and World War II, many relocations were made due to lack of building materials in urban reconstruction projects [

16]. Meanwhile, according to the results of the

Hikiya Construction Statistics Survey, which was constructed in Japan between 1980 and 2008, the main reason for the construction was that the first was urban planning, the second was land use, and the third was historical or attached building [

17]. Relocation has also been common in Taiwan since the end of the 19th century, and it was caused by feng shui, subsidence of the ground, and division of inheritance [

10]. In addition, the discovery and closure of mines, evacuation from frequent floods, and construction of dams were the causes. One of the most common reasons for relocation in the modern United States was the construction or expansion of roads [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Research on relocation for the purpose of conserving cultural heritage began to appear after the 2000s. Anelli, D., and Sica, F. (May 2020) and Springer, Cham., and Torri, M. C. (2011) analyzed the effects and expected results of relocation for the preservation of cultural and natural heritage, respectively, in economic and financial terms [

18,

19]. Examples of relocation and restoration of buried cultural properties include the London Mithraeum and the Thessaloniki Byzantine Crossroads. However, the process and logical feasibility, i.e., acceptance criteria, until the restoration of their relocation was permitted were not analyzed, and only the economic reason is known to be the largest [

20,

21,

22,

23].

2.2. Relocation Approval Process and Case Study in Seoul

As explained above, traditional Korean wooden architecture has been frequently performed since the past because it is very easy to relocate after dismantling. However, as it is not clear whether the purpose was to conserve cultural heritage, the subject of this study was limited to national cultural properties. In order to relocate cultural heritage designated by the state, the owner or related organization must apply for a change of status quo to the Cultural Heritage Administration. In this regard, the Cultural Heritage Committee deliberates and decides whether to permit or not. The criteria for permission to change the status quo specified in the Cultural Heritage Protection Act must first “do not affect the preservation and management of cultural heritage”, second “do not damage the historical and cultural environment of cultural heritage”, and third “conform to the cultural heritage basic plan and implementation plan”. This is flexible, but also inconsistent. Other than these, the permissible standards for the act of relocation have not been dealt with in detail any longer.

In Korea, Kee (2022) [

24] is the only research that analyzes the purpose of relocating architectural heritage. In 2022, Kee researched covering all the cases of relocated architectural heritages in Seoul since 1945. According to this research, there are 18 architectures, 20 cases. Two of these cases (Gwanghwamun gate in Gyeongbokgung palace (1967, 1994), Jongchinbu (1980, 2010)) were relocated twice each. Based on the contents revealed in this study, the diagram is shown in

Figure 1 based on the relocation promotion and progress of 20 cases.

The reason changed depending on who drove for it, and it also affected the approval and progress process. Among the 20 cases, the reason for the start of the relocation discussion was the urban development of the Seoul Metropolitan Government, with 10 cases being the most. Of these, four were state-owned Cultural Properties, and the City Planning Bureau or related Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government directly applied for approval of change the status quo (relocation), and six were privately owned Cultural Properties.

There were eight cases of relocation that were pursued for restoration. However, ‘restore’ here does not always mean ‘restoration of architectural heritage to its original site’. As an event project promoted by the Seoul Metropolitan Government (Bureaus other than the City Planning Bureau), there were five cases for restoring the historical placeness of a specific site. There were two cases for restoration to the original location promoted by the Cultural Heritage Administration and its predecessor organizations. There was one case for structural restoration by the president. In addition, there were two cases of relocation due to the personal decision of the structure or the land (site) owner [

24].

Based on this, the type in which the reason for relocation was ‘restoration’ was referred to as Type R. The type that the reason was urban development was referred to as Type D. Other reasons were referred to as Type E. In addition, within these three types, it was possible to subdivide according to the process of approval and progress of relocation, which was also related to when it was relocated. Taken together, it was classified by the driver, reason, process of approval and progress, and timing of relocation, and categorized into Type R1-Type R3 and Type D1-Type D3.

3. Classification of Case Types of Relocated Architectural Cultural Properties in Seoul

3.1. Relocation for Restoration

There were eight cases of relocation that were carried out for the purpose of restoration, and the main promoters include the president, the Cultural Heritage Administration, and other bureaus in Seoul Metropolitan Government (Bureaus other than the Urban Planning Bureau). However, this ‘restore’ did not always mean ‘restore to the original site’. Only two cases were promoted by the Cultural Heritage Administration, Type R2, to restore its original site, which can be seen as a trend since the 1990s. Then, why was the original site not kept in the previous cases of ‘relocation for restoration (Type R1, Type R3)’ and what was the ‘restoration’ for? In order to understand this, we analyzed each type of relocation in relation to its historical background and the position, pursued values, and intentions of each promoter.

3.1.1. Type R1: Relocation for Restoration Promoted by the President

Type R1 is a unique case that is related to the political and social background of Korea in the 1960s and was promoted by the president. Since the Cultural Properties Protection Law was enacted in the 1960s, this institutional conservation has made all Cultural Properties subject to strong government control [

25]. In addition, in the 1970s, the basic direction of cultural heritage conservation was to ‘

create an educational space that revives the cultural tradition of the nation, nurtures the spirit of the people, and learns the wisdom of overcoming national crisis’ [

26]. As a result, the number of cases of giving new meaning to existing Cultural Properties or creating new Cultural Properties had increased (

Appendix A. a3.). Against this background, then the president directly intervened in the management of cultural heritage and gave directions as desired, and the relocation site was decided according to his opinion.

Gwanghwamun was the main gate located on the south side of Gyeongbokgung palace, which was designated as Cultural Property in 1963. After that, during the Korean War (1950–1953), even the gate tower was burnt down, and only stone structures remained. A plan to restore it was started in 1966 under the direction of the president, which did not have the relocation in mind from the beginning. It meant ‘restoration’ in the form of reconstructing the gatehouse on top of the stone pillars left at the site at the time [

27,

28]. However, on November 16 of the same year, the location of the restoration of Gwanghwamun gate was changed to ‘

in front of the Central Government building (former building of the Japanese Government General of Korea)’ [

29] under the direction of the president. Although it was near the original site of Gwanghwamun gate, it was not the exact original site, and it meant that it would be used as the main gate of the Central Government building rather than the main gate of Gyeongbokgung palace. It is said that president did not specifically state the reason for this relocation. Instead, according to an interview with Bong-Jin Kang, who was in charge of designing the restoration of Gwanghwamun gate, if it was returned to its original site, it would be out of alignment with the front road, and some said that it was not aesthetically appropriate [

30]. This “front road” meant the current Sejong-ro, which is the national center street. At that time, Korea underwent colonial modernization, so the street of Sejong-ro and the outline of the surrounding buildings were formed around the axis set during the Japanese colonial period, that is, the former building of the Japanese Government General of Korea (the Central Government building at that time). Therefore, it was about 3.7 degrees away from the axis formed by the original site of Gwanghwamun gate. In addition, according to a newspaper article at the time, there were reasons such as ‘

a dignified symbol of Seoul’ or ‘

It also played a role in reviving the dignity of Gyeongbokgung palace by defeating the unpleasant colonial stone building’ (the Central Government building, former building of the Japanese Government General of Korea) [

29,

31].

As a result, in the case of Gwanghwamun gate of Gyeongbokgung palace (1967), although the original site could be specified, it was moved to a location a little further away from the original site for other purposes (

Figure 2).

3.1.2. Type R2: Relocation for Restoration to the Original Site Promoted by the Cultural Heritage Administration since the 1990s

These cases have been conducted since the 1990s, and at that time, the restoration and maintenance of Cultural Properties was actively started based on the economic growth achieved so far [

32]. They are also related to the social climate in which heritage conservation is beginning to be more important than urban development. International events, such as the 1986 Asian Games in Seoul and the Seoul Olympics in 1988, raised interest in the restoration of Cultural Properties. Additionally, in the 1990s, national projects such as ‘Restoring History’ were promoted as nostalgia spread to the public for spaces that had rapidly disappeared due to compressed modernization during the period of high economic growth [

33].

Under this background of the times, from the 1990s to the present, the purpose of conservation cultural heritage was nothing other than to pass on the properties of mankind and the nation to the next generation itself. This was quite different from the national Cultural Property management that was carried out in the 1960s with the intention of emphasizing ethnicity and education. Therefore, these cases of relocation can be interpreted as an attempt to conserve the original form and the original site and pass it down to the next generation rather than pursuing other purposes.

The restoration of Gwanghwamun gate to its original site was first mentioned in 1990, after it was relocated to the main gate of the Central Government building by the president in 1967. The Ministry of Culture and Public Affairs established the “Gyeongbokgung palace Restoration and Management Basic Plan” and started the restoration work at the same time as ‘to restore the spirit of the nation by reorganizing Gyeongbokgung palace, which was transformed and damaged during the Japanese colonial period, as well as to inspire the pride of the cultural nation and make it a tourist attraction of traditional culture’. Not only the exact original site of Gwanghwamun gate, but also the restoration of the surrounding environment was carried out. As a result, the Gyeongbokgung palace area, which had been incorporated into roads since the Japanese colonial period, was restored. In addition, the walls, decorations, and facilities on the left and right of Gwanghwamun gate were restored to their appearance in the Joseon Dynasty [

34,

35,

36] (

Figure 3a).

The Armed Forces Security Command, which was the landowner of Jongchinbu, carried out its relocation in 1980 to build a tennis court on the site. Later, in 2008, the Armed Forces Security Command was moved to the outskirts of the capital, and the site remained vacant. The National Museum of Contemporary Art was originally planned to be built on this vacant lot. However, according to the arguments of architectural experts, citizens, and the Cultural Heritage Administration, the relocation of Jongchinbu to their original site began to be considered. In 2009, an excavation survey was conducted on the site, and not only traces of the site of the Jongchinbu, but also remains from the early Joseon Dynasty and the late Goryeo Dynasty were discovered. Later, in 2010, the decision of the Minister of Culture finally decided to relocate Jongchinbu to its original site. Relocation work on the original site was completed in 2013, and for this purpose, the design of the National Museum of Contemporary Art was changed [

37] (

Figure 3b).

3.1.3. Type R3: Relocation Promoted by the Other Bureaus in Seoul Metropolitan Government around the 1990s

As mentioned earlier, international events held in Seoul, such as the 1986 Asian Game and the 1988 Olympic Game, raised interest in building the city’s image and identity. As a solution to this, emphasis on urban historicity was suggested. Comparing the history of Seoul Comprehensive Plans, it can be seen that from 1990, the city’s history, culture, and environmental conservation began to be treated as important, and the concept of ‘

historical and cultural assets’ appeared for the first time at this time [

38]. That is, 1990 was the year when Seoul began to actively conserve, manage, and utilize cultural heritage at the level of the local government.

Cases of relocations carried out for this reason include the “Gyeonghuigung Restoration Project” promoted by the Seoul Olympic Preparatory Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government and the “Namsangol Hanok Village Project” promoted by the Seoul City 600 Years Commemorative Project Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government. All of these started with the ultimate goal of ‘restoring the historical placeness’ of a specific site, but it was not a restoration of the original site according to a rigorous historical investigation. This is because the “Gyeonghuigung Restoration Project” could not be verified, and the direction of the “Namsangol Hanok Village Project” was changed to the creation of a theme park-like place according to the opinions of the citizens. As such, Type R3 could not be regarded as restoration to the original site at all as a result. However, since all of these five cases were regionally designated Cultural Properties, not nationally designated Cultural Properties, it was possible to relocate them without approval from the Cultural Heritage Administration as part of the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s project [

24].

The relocation of Heunghwamun gate in 1987 was part of the “Gyeonghuigung Palace Restoration Project” promoted by the Seoul Metropolitan Government, which began with ‘

the aim of providing traditional cultural places compared to the Asian Game and Olympics’ [

39]. In 1984, the Seoul Olympic Preparatory Bureau in the Seoul Metropolitan Government conducted Cultural Properties management and park creation as part of the event conditions, including the restoration of Gyeonghuigung palace and the creation of Gyeonghuigung Neighborhood Park. At the meeting of the Seoul regional Cultural Heritage Committee on 25 January 1985, it was discussed to create a museum and construction and park on the site of Gyeonghuigung palace and restore the structures. To this end, Seoul Olympic Preparatory Bureau requested cooperation from each owner to relocate and restore the buildings that were forcibly sold and scattered—several buildings were relocated to each different sites—during the Japanese colonial period. However, with the exception of Heunghwamun gate, the relocation failed due to the owner’s refusal. In addition, Heunghwamun gate failed to confirm its original site, and the site presumed to be the original location was already a private property and another building was built. Therefore, it had to be relocated to the vicinity of the original site rather than the original site [

40,

41,

42]. As such, the “Gyeonghuigung Palace Restoration Project” did not proceed as planned. Therefore, Seoul Olympic Preparatory Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government planned a policy of ‘

avoiding large-scale restoration projects and installing information boards’, and changed the direction of creating a historical and cultural place to show, such as the construction of the Seoul Museum in Gyeonghuigung palace site [

43]. At that time, many citizens and architectural experts criticized the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s decision, and in 2018, Jongno-gu, Seoul, established “Comprehensive Management Plan for the Gyeonghuigung Palace Site” to correct the wrong restoration in the past and remove the Seoul Museum (the present Seoul Museum of History) [

44] (

Figure 4a).

Namsangol Hanok Village, which was constructed by relocating four hanok (traditional Korean house) houses in Seoul, started with “Restoration of original Namsan’s Image”, which is one of the “Celebration for Seoul’s 600th anniversary as the Capital of Korea”. This was carried out by reflecting the opinions of the Citizens Committee for the Celebration for Seoul’s 600th anniversary as the Capital of Korea formed in 1992. The Citizens Committee of 100 People to Restoration of original Namsan’s Image, which was involved in this project, tried to display the houses of noblemen and their daily life by revitalizing the placeness in the Joseon Dynasty, adopting the old nickname of the place, ‘

Namsangol Seonbichon’ [

Appendix A. a4.]. However, according to historical evidence, Namsangol is a place where the fallen nobles and poor scholars lived, and it did not match the hanok of the wealthy class that were being relocated at that time. The reason for this was that the direction of the project was changed according to the opinions of citizens during the project. Citizens wanted more ‘

characteristic recovery of new functions’ and ‘

exhibition and viewing activities rather than physical recovery of dead history’. Therefore, rather than restoration based on rigorous historical evidence, it was changed in the direction of creating a historical and cultural place with a theme park-like character and an open-air museum [

45,

46,

47] (

Figure 4b).

3.2. Architectural Heritages Pushed out by Urban Development

These cases can be divided into three periods—the 1960s and 1970s, the late 1970s and early 1990s, and after the 2000s—depending on the subject of the relocation and the type of Cultural Property. This classification is a phenomenon that occurs because the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s pursuit of urban development plans has changed. All cases in the 1960s and 1970s were state-owned Cultural Properties, and the City Planning Bureau and related Bureaus in Seoul Metropolitan Government promoted the relocation for road construction. On the other hand, all cases after the late 1970s were private Cultural Properties. Designated Cultural Properties were targeted until the early 1990s and registered Cultural Properties after the 2000s [

24].

Considering that registered Cultural Properties do not require permission to change the status quo in case of relocation, it can be seen that since the 1990s, even if there has been no request for permission to change the status quo due to urban development, all have been rejected. In the 1960s and 1970s, modernization, urbanization, and urban development were considered priority values, and, in particular, convenient road networks were intensively constructed [

48]. As a result of marking the original location of the case of the relocation at this time above, it was found that all were on the main road side (

Figure 5a).

After the 1970s, urban redevelopment began [

49], and most of the original locations of cases relocated at this time were also included in the redevelopment district, and it can be seen that all of them were relocated outside the redevelopment district (

Figure 5b). After the 2000s, as the redevelopment area expanded to outside the city center, registered Cultural Properties in this area became subject to relocation.

3.2.1. Type D1: Cases at the Request of the City Planning Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government in the 1960s and 1970s

In all cases of this type, the City Planning Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government directly applied for change the status quo, decided the relocation site, and carried out construction. These include Daehanmun gate in Deoksugung palace (1968) (

Figure 6), Sajikdan gate (1973), Gwanghuimun gate (1974), and Independence Arch (1978) (

Figure 7). All of them were carried out in order to secure land for road widening or expansion, and as they were all state-owned Cultural Properties, relocation was approved through the same process.

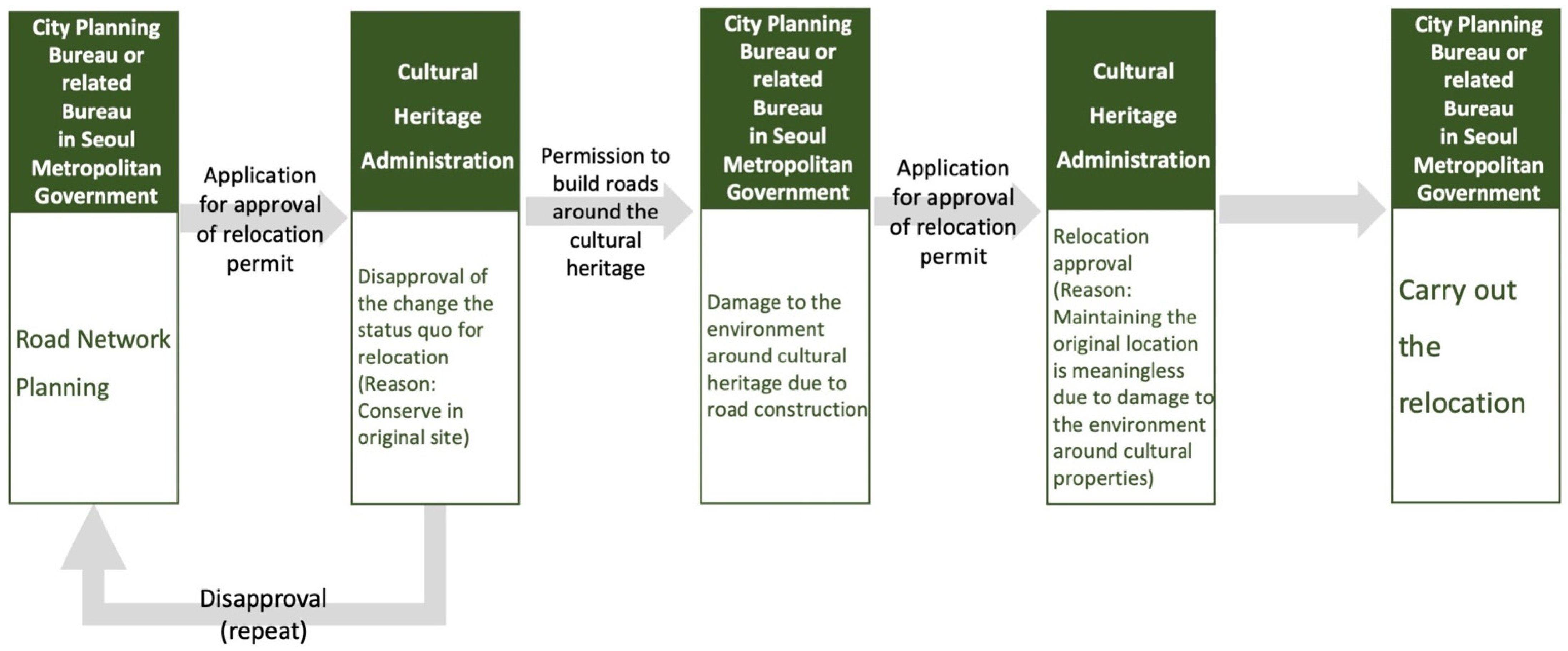

The process is as follows (

Figure 8). First, the City Planning Bureau or related Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government had established road plans without consulting the Cultural Heritage Administration [

50]. They make a request to the Cultural Heritage Administration to obtain approval for the relocation of the cultural heritage just before starting this urban planning work, and they go through the process of being disapproved more than once. The Cultural Heritage Administration did not approve the relocation under the simple principle of valuing the ‘original site’, but on the one hand, road construction was permitted in the periphery of the protected area that did not directly conflict with the architectural heritage.

As a result, the visual elements—landscape—and functional elements—accessibility—etc., were damaged due to the newly built roads around the cultural heritage. Then, public opinion turned to favor the relocation, and, at this time, the City Planning Bureau or related Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government repeatedly requested approval for the relocation, eventually obtaining approval for the relocation. In this relocation process, three types of participants appear. Among them, City Planning Bureau or related Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government, the Cultural Heritage Administration showed consistent attitudes from beginning to end, but citizens—opinion through the media—did not. Because the cases were state-owned, citizens were able to actively express their views. They valued overall harmony, that is, integrity, scenery, and accessibility, more important than the ‘original site’. These citizens’ opinions played a decisive role in whether to relocate, especially in the case of Daehanmun gate in Deoksugung palace (1968) and Independence Arch (1978). Their relocation site was decided unilaterally by the City Planning Bureau, and they were mainly relocated to the nearest location away from the site to be developed [

24,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

3.2.2. Type D2: Relocation at the Request of the Owner, from Late 1970s through Early 1990s

Among the relocation by urban development, Dojeonggung Gyeongwondang (1978), former Belgian Consulate (1980), Han Gyu-seol’s House in Janggyo-dong (1980), and Gaksimjae in Wolgye-dong (1990), which were concentrated from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, were road construction or redevelopment. The owner was the subject who directly promoted their relocation, but it can be said that it was indirectly affected by the City Planning Bureau and related Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government. Looking at the application for approval of the change the status quo (relocation) and the process through the records at the time, it can be seen that the approval of the relocation was relatively easy as the cultural heritages were privately owned [

24,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63].

3.2.3. Type D3: Relocation of Registered Cultural Properties at Owner’s Request since the 2000s

Type D3 is the same as Type D2 in that the owner promoted the relocation under the influence of urban development. However, Type D3 differs in that they are all ‘registered Cultural Property’. In Korea, the ‘registered Cultural Property’ system was introduced in 2001. Unlike designated Cultural Properties—Type D1 and Type D2—it focuses on reporting and induces voluntary protection efforts of owners through relaxed protective measures, such as guidance, advice, and recommendations. In addition, it allows repairs to the extent that the appearance does not change significantly, and promotes active utilization. To this end, management standards are relaxed and subsidies for tax and repair are also provided.

In other words, in the case of registered Cultural Properties, permission to change the status quo is not required, except in special cases. Therefore, it can be judged that there was no request for permission to change the status quo due to urban development or was rejected after the 2000s. In addition, the difference is that the cases of Type D2 were architectural heritage located in the city center, while the cases of Type D3 were also located outside the city center. This phenomenon is because urban redevelopment in Seoul first began in the city center and is spreading to the outskirts of the city today [

24,

64,

65].

3.3. Type E: Relocation for Other Reasons

Type E is a case in which the owner of the building or the owner of the land promoted relocation for personal benefit without being influenced by a specific period or social background. These include Sungjeongjeon (1975), Jongchinbu (1980). All of their change the status quo permit documents say that it is for the protection and utilization of the architectural heritage. However, referring to other records of the Cultural Heritage Administration at the time, it was found that Jongchinbu (1980) was for the landowner’s use of the land [

24,

66,

67].

4. Priority Value of Architectural Heritages at the Time as Seen through the Trend of Approval of the Relocation

The various backgrounds of the relocation as described above reflect the perceptions and attitudes towards architectural heritage by era and by subject. In this section, we analyze these by targeting 4 out of 7 types. The reason for excluding Type D2, Type D3, and Type E is that since they are private cultural properties, the owner’s personal perception and values would have influenced them. On the other hand, Type D1, Type R1, Type R2, and Type R3 are relocations led by the President, Seoul Metropolitan Government, and the Cultural Heritage Administration, showing the national attitude toward architectural heritage and representing the times.

4.1. Establishment of Value Classification System for Relocated Architectural Heritage

As explained in the introduction, several international principles for the preservation of cultural heritage by UNESCO and ICOMOS state that the architectural heritage should be conserved in its original site. In other words, the concept of ‘conservation of architectural heritage’ includes not only the structure on the site, but also the original site. However, the act of relocating is an act of separating the two, namely, the structure and the land. In other words, if the structure has conservation value but the existing site has no or low conservation value, relocation is allowed.

On the other hand, various classifications exist for the value of cultural heritage. In this paper, Alois Riegl’s classification of values of monuments (1903) was adopted. According to Heinz Horat, Alois Riegl divided the values of monuments into the ‘

values of the past’ and the ‘

values of the present’ in the first stage [

68]. In the second stage, he identifies a set of

past (memory or commemorative) values (Erinnerungswerte)—precisely deliberate commemorative value (gewollter Erinnerungswert), historical value (historischer Erinnerungswert), and age value (Alterswert)—and a set of

present-day values (Gegenwartswerte)—namely use value (Gebrauchswert) and artistic value (Kunstwert), the latter further subdivided into newness value (Neuheitswert), and relative artistic value (relative Kunstwert; i.e.,

changing tastes) [

69]. In Riegl’s theory,

historical value started in the Renaissance with the development of official measures of preserving ancient buildings, for example, with the role Raphael as conservator under Leo X.

Age value starting from the seventeenth century and lasting up to the twentieth century could be linked with the actual traces of age in artworks and buildings, such as decay, which resulted in picturesque aesthetics and genuineness. It contributed to the aura and authenticity of an object, and created a heritage context for nostalgia. As such, age value contradicts historical value. Both historical and age value are considered “

commemorative values or values of the past”; Riegl contrasts these with the two “

present-day values” of

use-value and

art-value. The context of a

use value is derived from its utilitarian service to society [

70].

In this paper, these two values of Riegl are set as the standard. In addition, a value classification system for relocated architectural heritage was established. As a result, it is largely divided into the ‘value of the structure’ and the ‘value of the site’, and it is divided into the ‘values of the past’ and the ‘values of the present’, respectively (

Figure 9).

4.2. Values Pursued by Case Type

For the four types classified in

Section 2, the value pursued as the first priority when relocating was marked with ●, the secondary value pursued as

○, and the value completely ignored as ×.

Table 1 shows. Cases that are difficult to judge are left blank. The fact that the architectural heritage was conserved even if it was moved without being demolished can be interpreted as basically respecting the ‘values of the past’ of the structure in all cases.

Type R1 which used architectural heritage as a monument and a political symbol, can be interpreted as pursuing the ‘values of the present of the structure’ the most. Type D1 was to secure land for road construction in Seoul Metropolitan Government. In other words, it can be said that the ‘values of the present of the site’ was pursued as the first priority by completely sacrificing the ‘values of the past’ of the site. Type R3 pursued the ‘values of the present of the structure’ the most because it was intended to restore the historical placeness by moving the architectural heritage from another location to a specific site. However, there is a record that, among Type R3, 4 houses in Namsangol Hanok Village (1993) preferentially selected those under a situation in which conservation was threatened by their original location being set as a redevelopment area. Therefore, it can be said that the ‘values of the present of the site’ for urban development was also pursued secondary. The original site of Type R2, Gwanghwamun gate in Gyeongbokgung palace (1994) and Jongchinbu (2010), were used as roads or where a new modern building was planned. However, giving up the ‘values of the present of the site’ and relocating and restoring the architectural heritage to its original site means that the ‘values of the past of the site’ was most respected.

As a result of this analysis, it can be seen that the conservation priority value of architectural heritage has changed significantly since 1990. From the 1960s to the 1990s, there was a tendency to separate the structure and site of architectural heritage. In particular, the structure was regarded as an object of conservation, but its original site (land) was not recognized as an object of conservation. It was after the 1990s that the conservation value of the original site (land) began to be recognized.

In addition, from the 1960s to the 1990s, there was a tendency to prioritize the ‘values of the present’ over ‘values of the past’ of architectural heritage (structure and site). Due to this perception, it can be seen that the relocation of architectural heritage was allowed for the use of structures or land. After the 1990s, their ‘values of the past’, especially ‘values of the past of the site’, began to be recognized, and architectural heritage lost its original site due to past relocation could be returned to its original site.

5. Conclusions

As described above, the criteria for allowing relocation of architectural heritage in Seoul were investigated and the value priorities in conservation were analyzed. As a result of the analysis, their relocation was permitted mainly for the purpose of ‘restoration’ or ‘urban development’.

The relocation for ‘restoration’ did not necessarily mean ‘restoration to its original site’. It can be seen that it also includes the meaning of restoring the past in terms of form or placeness. These cases have continued to occur since the 1960s and have been omitted or easily approved for the change of the status quo. There was a total of eight relocations for restoration.

Type R1 is Gwanghwamun gate in Gyeongbokgung palace (1967), and is related to the historical background of the dictatorship of the 1960s. The purpose of conserving cultural heritage was to converge the nation, justify the government, and create an image of the city. Type R2 was a movement to restore what has been moved in the past to its exact original position. This tends to be the case after the 1990s, that is, relatively modern times. This is related to the idea that today, the purpose of conserving cultural heritage is to pass it down to future generations. Type R3 was promoted as a relocation in the 1990s to restore the historical sense of place in Seoul. It was for urban events such as 1988 Seoul Olympics and Seoul 600th Anniversary Event.

A total of 10 cases occurred due to urban development. Even in these cases, there is a clear difference according to the time period. Type D1 was a national cultural heritage from the 1960s to the 1970s, and was promoted by the City Planning Bureau or related Bureau in Seoul Metropolitan Government. The D2 type was a case from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, and the owner applied for permission to relocate it because it was a private cultural property. Type D3 is from the 2000s and is subject to privately registered cultural properties. The reason for such detailed division by period can be interpreted as the changes pursued in Seoul’s urban planning from the 1960s to the present.

For the cases categorized in this way, it was analyzed by which priority value among the various value systems of architectural heritage was approved relocation. The act of relocating is the act of separating architectural heritage into structure and site. In addition, in order to separate the values of the two, Alois Riegle’s classification of monuments (1903) was applied. As a result, from the 1960s to the 1990s, structures were considered objects of conservation, while their original site (land) was not recognized as objects of conservation. In addition, at this time, the ‘values of the present’ was prioritized over the ‘values of the past’ of architectural heritage (structure and site). It has been since the 1990s that the ‘values of the past’ of the site began to be recognized, and as we became closer in recent years, the relocation of architectural heritage tended to be carried out only for its return to its original site.

This study started with a question about the standard for allowing relocation of architectural heritage, which has been presented unclearly until now. By analyzing the actual relocation of architectural heritage in the Seoul area, it was intended to clarify ‘in what cases was relocation permitted?’. In addition, it was analyzed what value priorities acted on this permission background. This study is meaningful in that it is representative in that Seoul is the capital and largest city of Korea, and it is a fragmentary study that can examine the history of cultural heritage recognition and value from the 1960s to the present.

Meanwhile, the method of this study can be applied to cities other than Seoul. By analyzing the permissible standards for relocating or changing the status quo in each city, it is possible to know what the value of the architectural heritage that was important in the area was at that time. When such studies are accumulated, it will be helpful to refine, objectify, and stipulate the legal acceptance criteria for changing the status quo and relocating, and as a result, systematization of cultural heritage management will be created.