Critical Components of Airport Business Model Framework: Evidence from Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Business Model Conceptualisations

| Authors | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Porter [27] | The definition of a business model, most often, refers to how a firm does business and creates revenue. Simply put, this model sets a low bar for setting up and building a firm’s operation. |

| Chesbrough and Rosenbloom [31] | In a general sense of business model, it is how a business is run, whereby a firm can organise itself to generate revenue. It shows how a firm makes money by indicating its standing in the value chain. |

| Magretta [38] | A business model tells the story of how a firm sells its products and delivers value. |

| Hedman and Kalling [23] | Business models are used to illustrate the key components of a company. |

| Morris, et al. [30] | It is the firm’s economic model. It involves profit generation, revenue sources, methods of pricing, cost structures, profit margins and expected volumes. |

| Osterwalder, et al. [40] | A business model is a conceptual tool containing elements that show the relationship and present the logic of a specific business. It describes the company value offered to various customer segments. In addition, it shows the architecture and networks of partners that deliver value to create and sustain revenues and profits. |

| Chesbrough [42] | Business models perform two crucial functions. They act as value creators and value captors. They define a series of activities from purchasing to final customers. |

| Zott and Amit [19] | A business model explains how a firm is connected with external parties, and how a firm interacts in economic exchanges to generate value for external stakeholders. |

| Zott and Amit [20] | A business model is a structural template describing a firm’s focal transactions with all stakeholders. |

| Baden-Fuller and Morgan [25] | A business model is a means of describing and classifying businesses. It operates as a site for scientific investigation and provides guidelines to managers. |

| Amit and Zott [36] | A business model is the bundle of activities aimed to serve the market needs and parties, and it represents how these activities are linked together. |

| Chesbrough [37] | A business model is a model fulfilling these functions:

|

| Demil and Lecocq [43] | A business model may refer to the articulation of various company activities designed to provide value to customers. |

| Giesen, et al. [15] | Business model components relate to these questions:

|

| Osterwalder and Pigneur [45] | A business model is a description of the rationale on how a firm creates, delivers and captures value. |

| Teece [47] | A business model explains the architecture of value creation and delivery, and captures the business mechanisms it uses. |

| Zott and Amit [49] | A business model acts as a system of activities transcending the firm’s pinnacle and boundaries that allow a firm to create and share value. |

| Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart [44] | They suggested that a business model contains the components that inform managerial decisions as to the manner in which a firm should operate, the consequences of those managerial decisions and their impacts on the firm’s strategy for value creation and value capture. |

| Cavalcante, et al. [33] | They posit a business model as a tool to provide stability for the development of a firm’s activities. This model is flexible and subject to change. |

| Zott, et al. [50] | Business models provide a holistic view on how a firm runs its business. They explain not only how value is generated but also how it is captured. |

| Trimi and Berbegal-Mirabent [39] | A business model explains how a firm delivers value to users, where to allocate the money for the firm’s sustainability and how to run the company. |

| Boons and Lüdeke-Freund [34] | A business model provides a plan that indicates how new ventures are able to become profitable. |

| Zott and Amit [32] | Business models depict the ways a firm does business. They are crafted to best provide customer satisfaction. |

| Bocken, et al. [51] | A business model is defined by three components: value proposition; value creation; delivery and value capture. |

| DaSilva and Trkman [26] | A business model is the combination of resources through transactions to create value for a firm and its customers. |

| Amit and Zott [21] | A business model explains the system of activities carried out by a firm, its parties and the mechanisms linking these business activities to one another. |

| Joyce and Paquin [52] | A business model is a rationale of how a firm creates, delivers and captures value. |

| Wirtz, et al. [24] | Apart from value creation and market component considerations, a business model simplifies and represents a firm’s related activities to secure a competitive advantage. |

| Massa, et al. [29] | A business model explains how a firm is run in order to achieve its goals, such as profitability, growth, interaction with society and impacts, among others. |

| Saebi, et al. [46] | A business model is an architecture linking a firm’s value proposition, market segment, value chain structure and value capturing. |

| Geissdoerfer, et al. [53] | Business models are defined as simplified versions of value proposition, creation, delivery and capture. They represent the interactions among these elements within a firm’s unit. |

| Hahn, et al. [54] | A business model is the content, structure and control of transactions designed to create value over the exploitation of business opportunities. |

| Teece [48] | A business model illustrates the architecture whereupon a firm generates and delivers value to users. It describes the mechanisms for capturing a share of value. It is a combined set of components, including costs, revenues and profits. |

| Afuah [13] | A business model is a set of activities performed to generate and utilise business resources in order to create, deliver and monetise benefits to customers. |

| Di Tullio, et al. [55] | A business model is a communication device that underlies the value-creation process. |

2.2. Airport Business Model Literature

| Authors | Definition | Aspects of Studying |

|---|---|---|

| Baker and Freestone [58] | They did not clearly specify, but we can infer that they intended to describe how those airports do business. | The paper compared how two sampled airports from different scales embraced the airport city concept to develop their properties commercially in response to changes. |

| Frank [10] | The business model analyses and depicts the way the firm operates. | The author suggested a structure for airport business models, comprising the customer value proposition, breakthrough rule changing, regulators, key profit formula, stakeholders, governance mix, reform opportunity cost, key resources, key processes, network value, risk and externalities. |

| Kalakou and Macário [12] | An attempt to conceptualise business operations through a model, treating it as an operational tool to improve the firm’s performance and revenues. | They explored a new framework for airport business model design by adapting elements from Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010). The authors presented additional building blocks, including the so-called regeneration factor, which includes expected investments and expected returns. The study concluded that high-performance airports shared the same airport business model components. |

| Everett Jr [59] | A business model is part of a business plan. This schematic model provides an overall picture of a firm, and is more comprehensive than other revenue or operating models. | The paper presents the framework for developing airport operations in a changing business environment. Using the example of a small airport in the USA, the author adopted components from Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) to illustrate the application of the framework. |

| Efthymiou and Papatheodorou [60] | The authors did not give the definition, but we can interpret that it means how airports run businesses under changing environments. | The authors present how airport businesses evolve their operations during different periods of the aviation industry, in response to changing airline business models. |

| Rotondo [6] | The author defines a business model using three elements: structure, value proposition and the market. | The study aims to develop a systematic and theoretically founded framework with which to interpret airport business models. It provides a structured and comprehensive examination of strategic methods using an approach to evaluate business models, and demonstrates the application of the concepts using airports in Italy. |

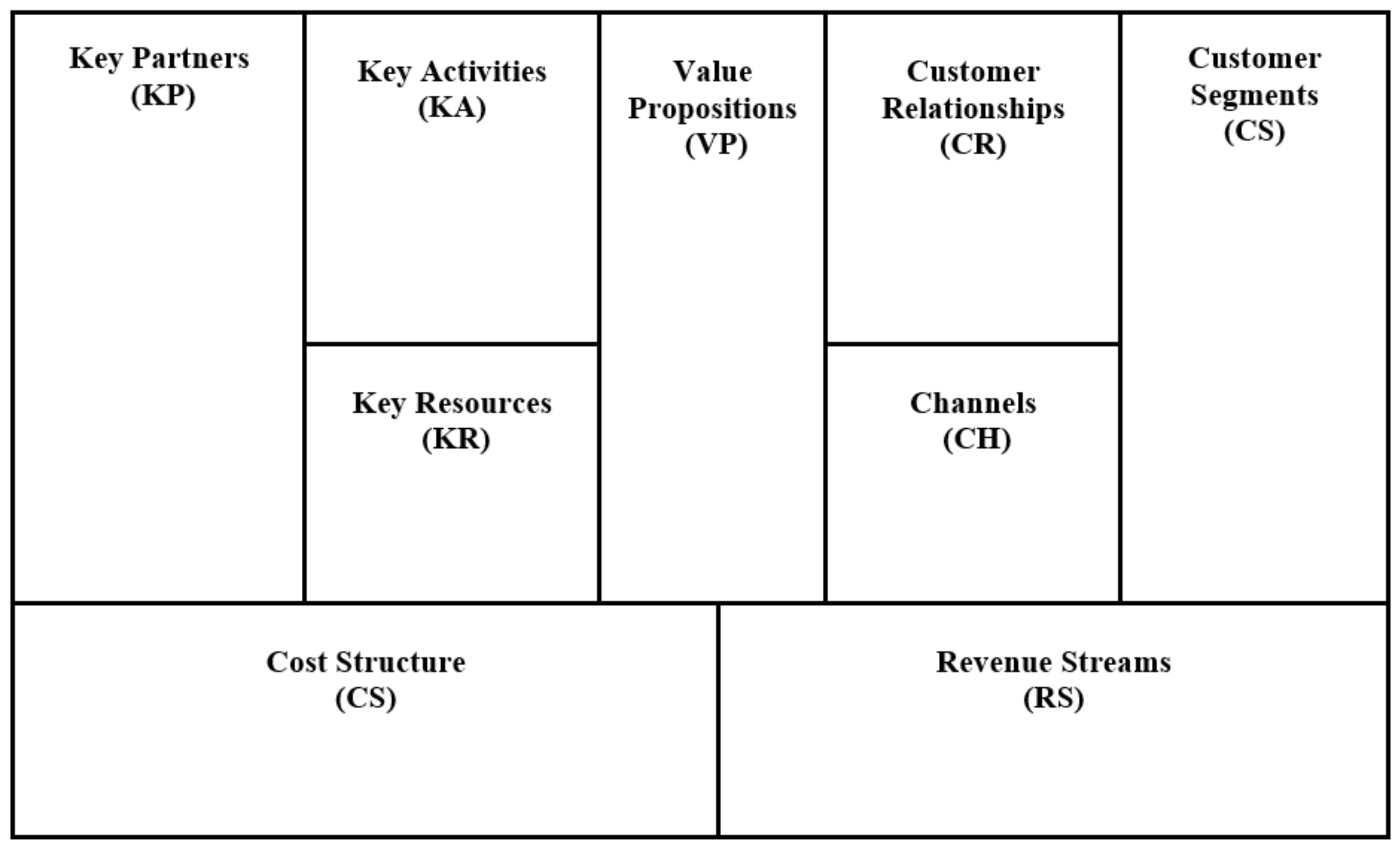

2.3. Analytical Framework of Business Model Design

- Customer Segments (CS) consider the different groups of customers being served. This block includes various groups of customers who are the source of earnings in a business. If a firm offered products and services to various CS, it would be required to justify and prioritise them to deliver the right value to the right groups. The CS can be categorised into mass markets, niche markets, segmented markets, diversified markets and multi-sided platforms or multi-sided markets that are specifically regarded as segmented for airport businesses.

- Value Propositions (VP) are the goods and services a firm offers that create value for each customer segment. It also indicates customer pain points and suggests solutions. VP involve these factors: newness, performance, customisation, design, brand, getting the job done, price, cost and risk reduction, and accessibility and usability.

- Channels (CH) refer to the selected channels where a firm communicates with each customer segment about proposing value. Finding the right channel helps a company raise awareness among customers about its products, and allows the company to assess the best mode to convey messages to customers.

- Customer Relationships (CR) elucidate the forms of interaction between a firm and each specific customer segment. CR can be divided into several categories. They include personal assistance, dedicated personal assistance, self-service, automated services, communities and co-creation.

- Key Resources (KR) enable VP to customers and markets, maintain CR with CS and generate revenues. KR can be classified as physical, intellectual, human and financial.

- Key Activities (KA) are a set of activities a firm needs to drive its business model. It explains the main activities a firm should undertake to deliver VP. Such activities include production, problem solving, platform provision or network management.

- Key Partnerships (KP) are the networks underlying a supplier–firm partnership. The aims of networking partnerships are optimisation and economies of scale, reduction of risk and uncertainty, and acquisition of activities and business resources to extend a firm’s capabilities.

- Revenue Streams (RS) show the revenue stream from each customer segment. This involves two different RS: transaction revenues and recurring revenues. Transaction revenues are payments from one-time customers, while recurring revenues refers to continuous payments from customers. To generate RS, a firm might sell assets; collect usage, brokerage and subscription fees; or lend, rent, lease, licence or sell advertising.

- Cost Structure (CS) reflects important costs incurred from the other eight block operations. Once the other blocks are detailed, it is possible to calculate all inherent costs that can then be minimised. However, this depends on the type of business model that might fall between being cost-driven and value-driven.

3. Research Methodology

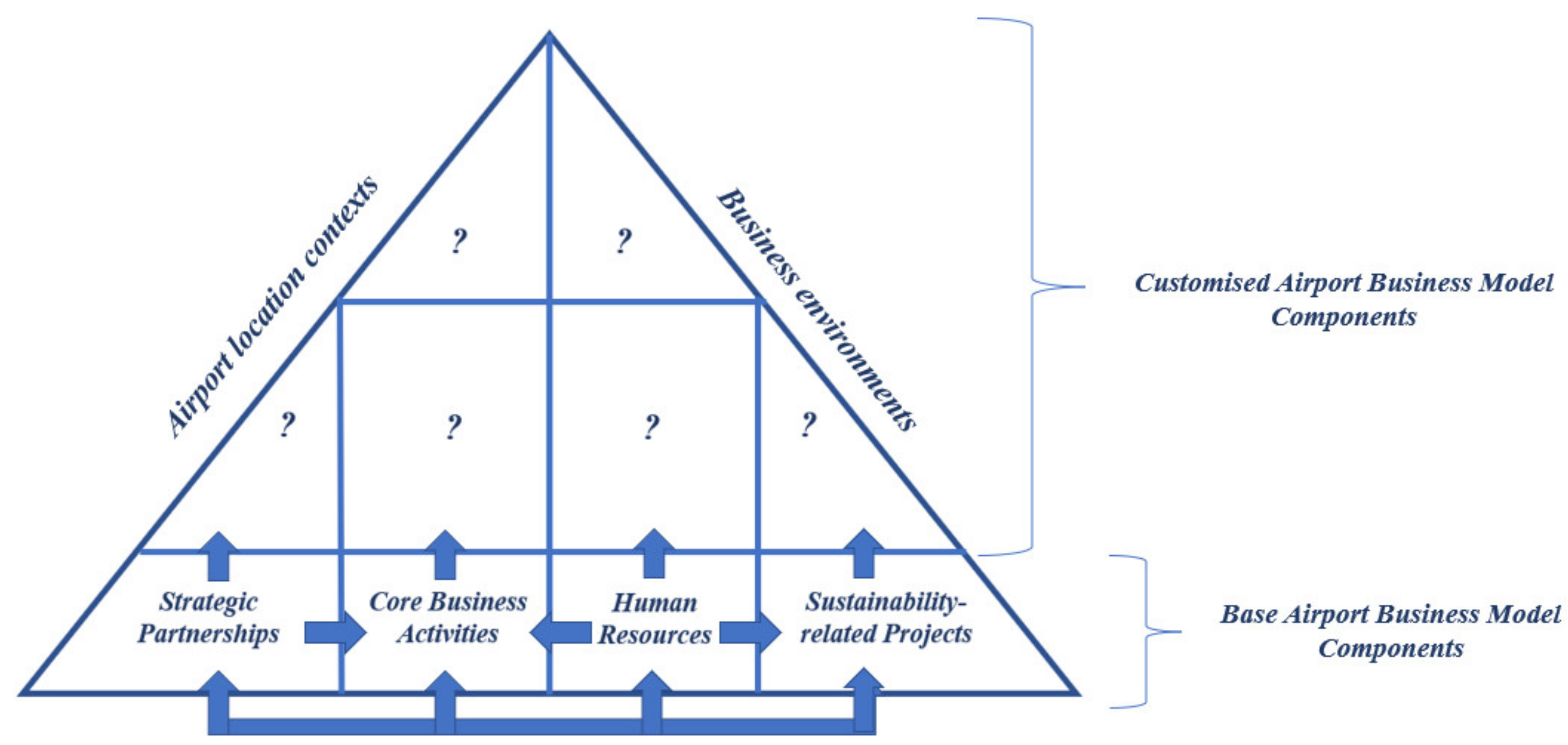

4. Findings

4.1. Strategic Partnerships

4.2. Core Business Activities

- (1)

- Business development:

- (2)

- Destination development:

4.3. Human Resources

- (1)

- Skills necessary for airport people:

- (2)

- Incentives towards their operations:

- (3)

- Manpower planning:

4.4. Sustainability-Related Projects

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrew, D. Institutional policy innovation in aviation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2012, 21, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neufville, R.; Odoni, A. Airport Systems: Planning, Design, and Management; McGraw-Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A. How important are commercial revenues to today’s airports? J. Air Transp. Manag. 2009, 15, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutiphongdech, T.; Vongsaroj, R. Technical efficiency and productivity change analysis: A case study of the regional and local airports in Thailand. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 870–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, S.; Francis, G.; Humphreys, I.; Page, R. UK regional airport commercialisation and privatisation: 25 years on. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, F. An explorative analysis to identify airport business models. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2019, 33, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Gillen, D.; Tsionas, E.G. Understanding relative efficiency among airports: A general dynamic model for distinguishing technical and allocative efficiency. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2014, 70, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Josiassen, A. Frontier analysis: A state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutiphongdech, T. Airport technical efficiency and business model innovations: A case of local and regional airports in Thailand. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 28, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L. Business models for airports in a competitive environment. One sky, different stories. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2011, 1, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A. Managing Airports: An International Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kalakou, S.; Macário, R. An innovative framework for the study and structure of airport business models. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2013, 1, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A. Business Model Innovation: Concepts, Analysis, and Cases; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cucculelli, M.; Bettinelli, C. Business models, intangibles and firm performance: Evidence on corporate entrepreneurship from Italian manufacturing SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, E.; Riddleberger, E.; Christner, R.; Bell, R. When and how to innovate your business model. Strategy Leadersh. 2010, 38, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Lai, M.C.; Lin, L.H.; Chen, C.T. Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2013, 26, 977–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Shirokova, G.; Shatalov, A. The business bodel and firm performance: The case of Russian food service ventures. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Song, X.; Wang, D. Manufacturing flexibility, business model design, and firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business model design and the performance of entrepreneurial firms. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. The fit between product market strategy and business model: Implications for firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Business models. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerrock, K. The business model as a unit of analysis. In Social Entrepreneurship Business Models: Incentive Atrategies to Catalyze Public Goods Provision; Sommerrock, K., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hedman, J.; Kalling, T. The business model concept: Theoretical underpinnings and empirical illustrations. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Pistoia, A.; Ullrich, S.; Göttel, V. Business models: Origin, development and future research perspectives. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C.; Morgan, M.S. Business models as models. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaSilva, C.M.; Trkman, P. Business model: What it is and what it is not. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Strategy and the Internet. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. Business model innovation: Past research, current debates, and future directions. J. Strategy Manag. 2017, 10, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, L.; Tucci, C.L.; Afuah, A. A critical assessment of business model research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Schindehutte, M.; Allen, J. The entrepreneur’s business model: Toward a unified perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind. Corp. Change 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. The business model: A theoretically anchored robust construct for strategic analysis. Strateg. Organ. 2013, 11, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavalcante, S.; Kesting, P.; Ulhøi, J. Business model dynamics and innovation:(Re) establishing the missing linkages. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Crafting business architecture: The antecedents of business model design. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Business model innovation: Creating value in times of change. Work. Pap. WP 2010, 870, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magretta, J. Why business models matter. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 6, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Trimi, S.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J. Business model innovation in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 8, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Codini, A.P.; Abbate, T.; Petruzzelli, A.M. Business model innovation and exaptation: A new way of innovating in SMEs. Technovation 2022, 102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X. Business model evolution: In search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J.E. How to design a winning business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saebi, T.; Lien, L.; Foss, N.J. What drives business model adaptation? The impact of opportunities, threats and strategic orientation. Long Range Plan. 2017, 50, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business model design: An activity system perspective. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Spieth, P.; Ince, I. Business model design in sustainable entrepreneurship: Illuminating the commercial logic of hybrid businesses. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tullio, P.; La Torre, M.; Dumay, J.; Rea, M.A. Accountingisation and the narrative (re)turn of business model information in corporate reporting. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutiphongdech, T.; Vongsaroj, R. Airport business model innovations for local and regional airports: A Case of cultural entrepreneurship in Thailand. In Cultural Entrepreneurship—New Societal Trends; Ratten, V., Ed.; Spinger Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen, D. The evolution of airport ownership and governance. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2011, 17, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.C.; Freestone, R. The Airport city: A new business model for airport development. In Critical Issues in Air Transport Economics and Business; Macario, R., Voorde, R.V.d., Eds.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2010; pp. 150–164. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, C.R. Reconsidering the airport business model. J. Airpt. Manag. 2014, 8, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Efthymiou, M.; Papatheodorou, A. Evolving airline and airport business models. In the Routledge Companion to Air Transport Management; Nigel, H., Anne, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The Business Model Innovation Factory: How to Stay Relevant When the World is Changing; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, S. Will business model innovation replace strategic analysis? Strategy Leadersh. 2013, 41, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun Tie, Y.; Birks, M.; Francis, K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312118822927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jupp, V. The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins, A.R. Exploratory research in the social sciences. In Sage University Paper Series on Qualitative Research Methods (Vol. 48); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, K.R. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Applied Thematic Analysis; Sage: Singapore, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, P.C. Information Sources in Grey Literature: Guides to Information Sources, 4th ed.; Bowker Saur: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, H.R.; Hopewell, S. Grey literature. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis; Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Valentine, J.C., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Guo, J.; Zhuang, J. Analyzing passengers’ emotions following flight delays-a 2011–2019 case study on SKYTRAX comments. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunchongchit, K.; Wattanacharoensil, W. Data analytics of Skytrax’s airport review and ratings: Views of airport quality by passengers types. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 41, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishnani, N. Designing the World’s Best: Singapore Changi Airport; Page One Publishing: Singapore, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chutiphongdech, T.; Vongsaroj, R. The success behind the world’s best airport: The rise of Changi. Asia Soc. Issues 2022, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.-A.; Graham, A. Profitability in the airline versus airport business: A long-term perspective. J. Airpt. Manag. 2011, 5, 255–268. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen, D. The evolution of the airport business: Governance, regulation and two-sided platforms. In Proceedings of the Hamburg Aviation Conference, Hamburg, Germany, 20–21 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Airport Managements | Airport Scholars | Total Key Informants Collected | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privatised Airports | Private Airports | Public Airports (Central Unit) | Public Airports (Regional Units) | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| Business Model Components | Interview Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Customer Segments (CS) | Who are your customer segments or markets that your airport is serving? What segments allow you to achieve better business operations? |

| 2. Value Propositions (VP) | What values or types of services do you offer to those markets? How do these relate to your performance? |

| 3. Channels (CH) | Which channels do you find efficient for communicating or reaching your markets and delivering these values? |

| 4. Customer Relationships (CS) | How do you efficiently interact with each customer segment? |

| 5. Key Resources (KR) | What types of business resources, do you find, play a critical part in airport performance? |

| 6. Key Activities (KA) | What types of activities do you consider a performance driver for the airport business? |

| 7. Key Partnerships (KP) | Are there any stakeholders playing a critical part in your business operations? |

| 8. Revenue Streams (RS) | What are the key drivers of airport business revenue? |

| 9. Cost Structure (CS) | What are the significant costs from business operations that affect performance? |

| 10. Other Business Model Components | Apart from the following business model components, in your opinion, what types of business components should your organisation consider, to improve airport performance? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chutiphongdech, T.; Vongsaroj, R. Critical Components of Airport Business Model Framework: Evidence from Thailand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8347. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148347

Chutiphongdech T, Vongsaroj R. Critical Components of Airport Business Model Framework: Evidence from Thailand. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8347. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148347

Chicago/Turabian StyleChutiphongdech, Thanavutd, and Rugphong Vongsaroj. 2022. "Critical Components of Airport Business Model Framework: Evidence from Thailand" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8347. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148347

APA StyleChutiphongdech, T., & Vongsaroj, R. (2022). Critical Components of Airport Business Model Framework: Evidence from Thailand. Sustainability, 14(14), 8347. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148347