Demographic and Social Dimension of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Cities: Excess Deaths and Residents’ Fears

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 1.

- Crude death ratewhere D—total number of deaths during the calendar year, P—total mid-year estimated population or the total population of the middle of the year (as of 30 June). The constant 1000 means that CDR is the number of deaths per 1000 inhabitants.

- 2.

- Death rate due to COVID-19where —number of deaths due to COVID-19 during the calendar year, and –the total mid-year estimated population or the total population of the middle of the year (i.e., as of 30 June).

- 3.

- Death rate for population 65+where —number of deaths in population 65+, —the mid-year estimated population 65+.

- 4.

- Death rate due to COVID-19 for population 65+where —number of deaths due to COVID-19 in population 65+, and —the mid-year estimated population 65+.

3. Results: COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Cities 2020–2021

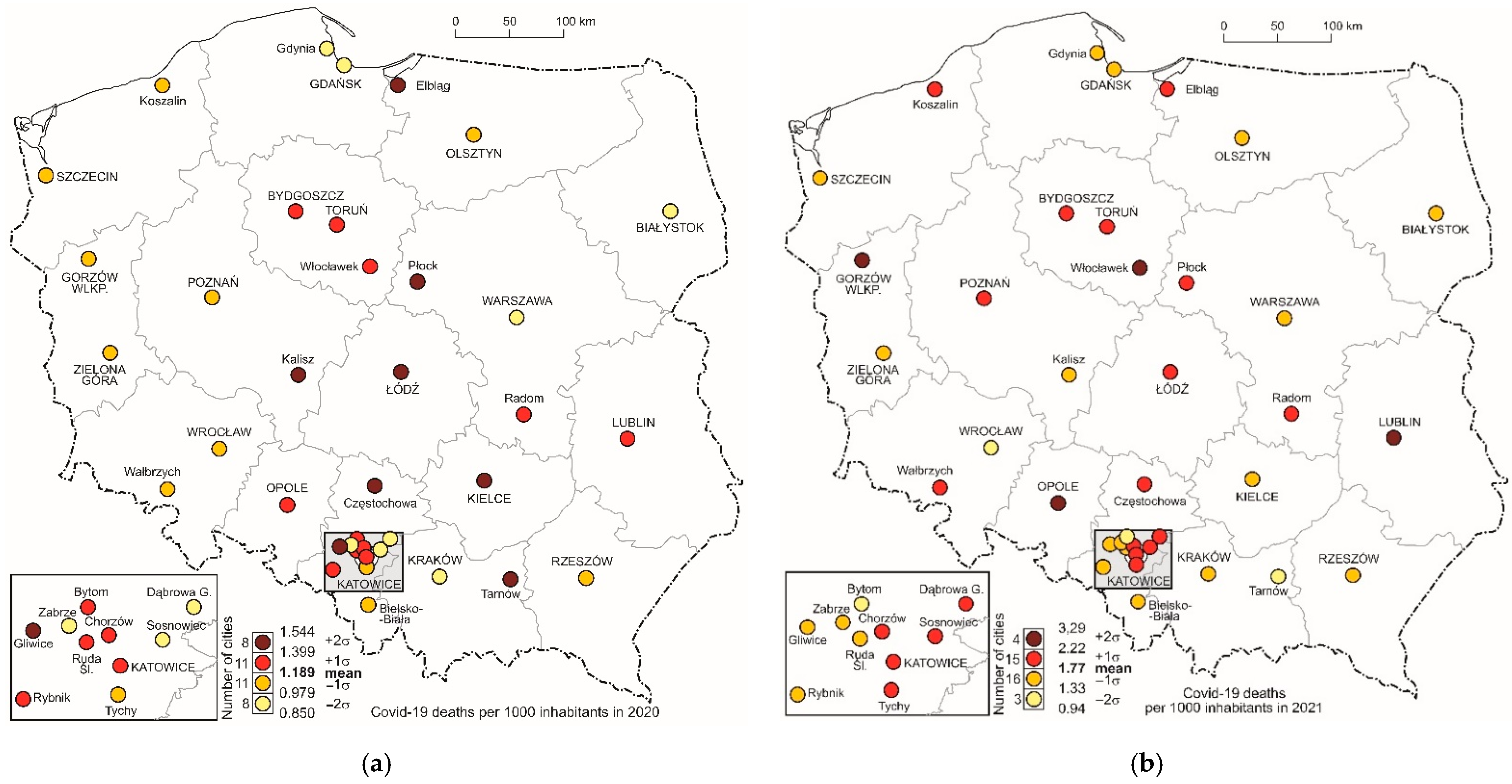

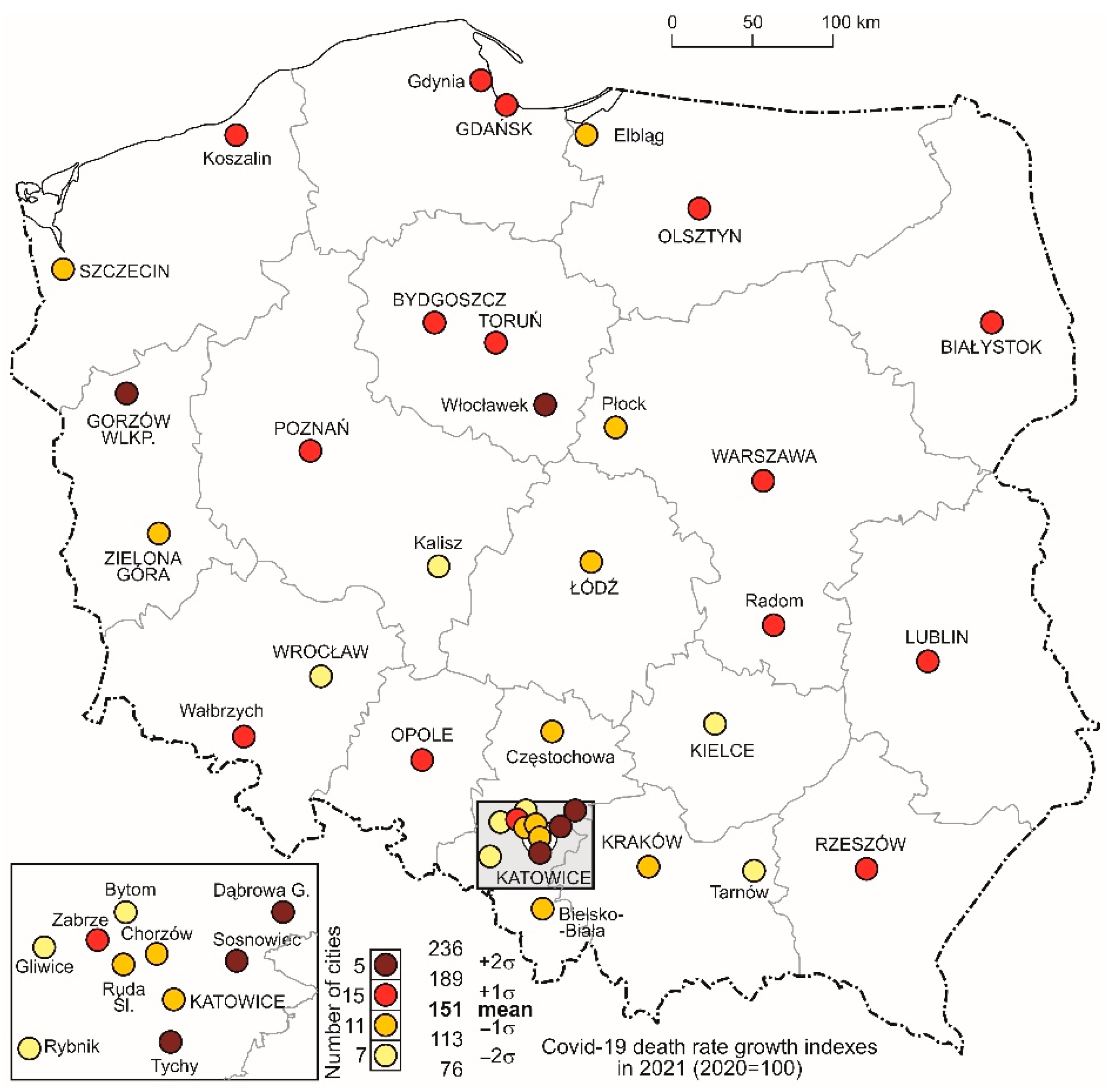

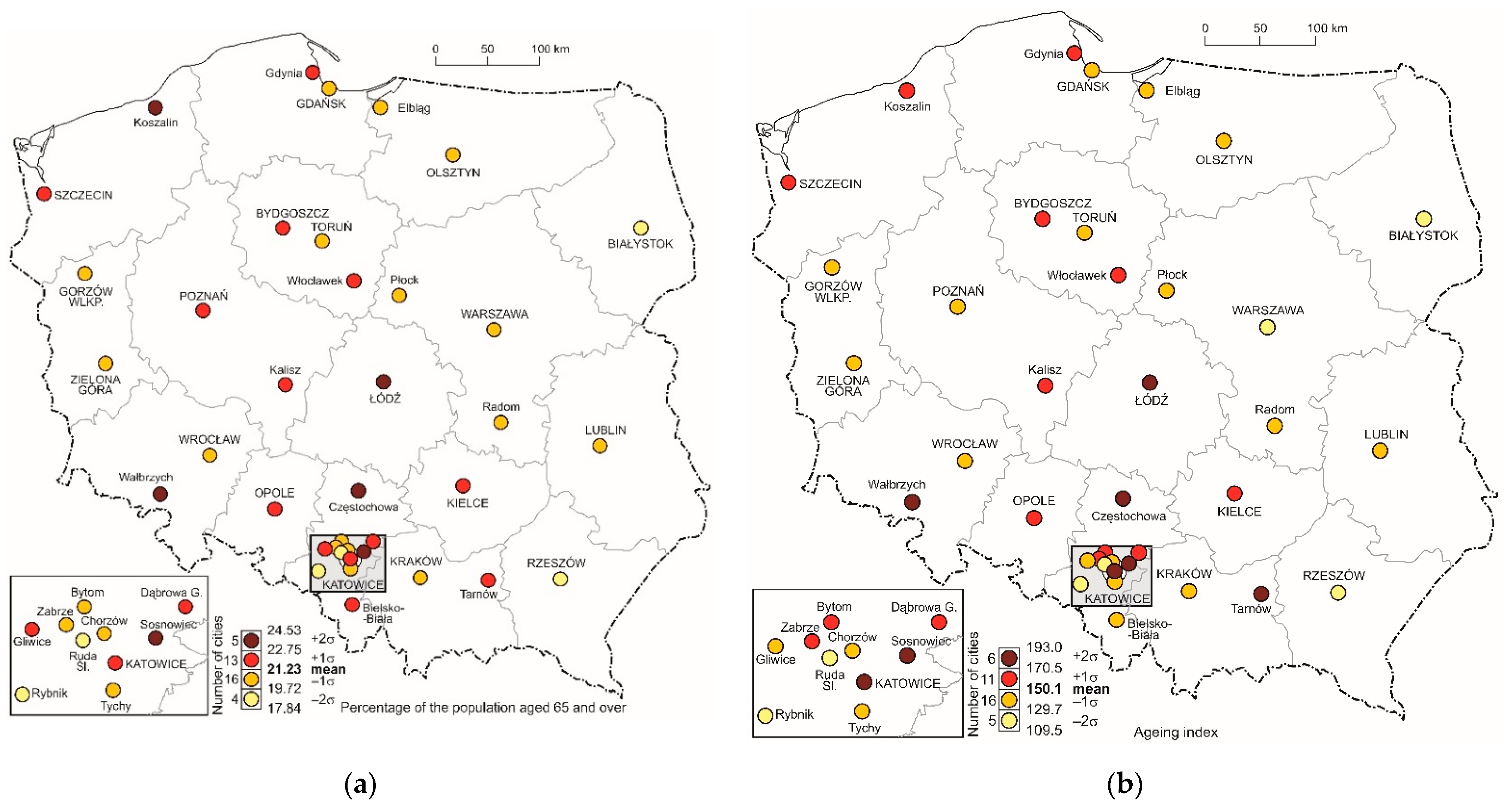

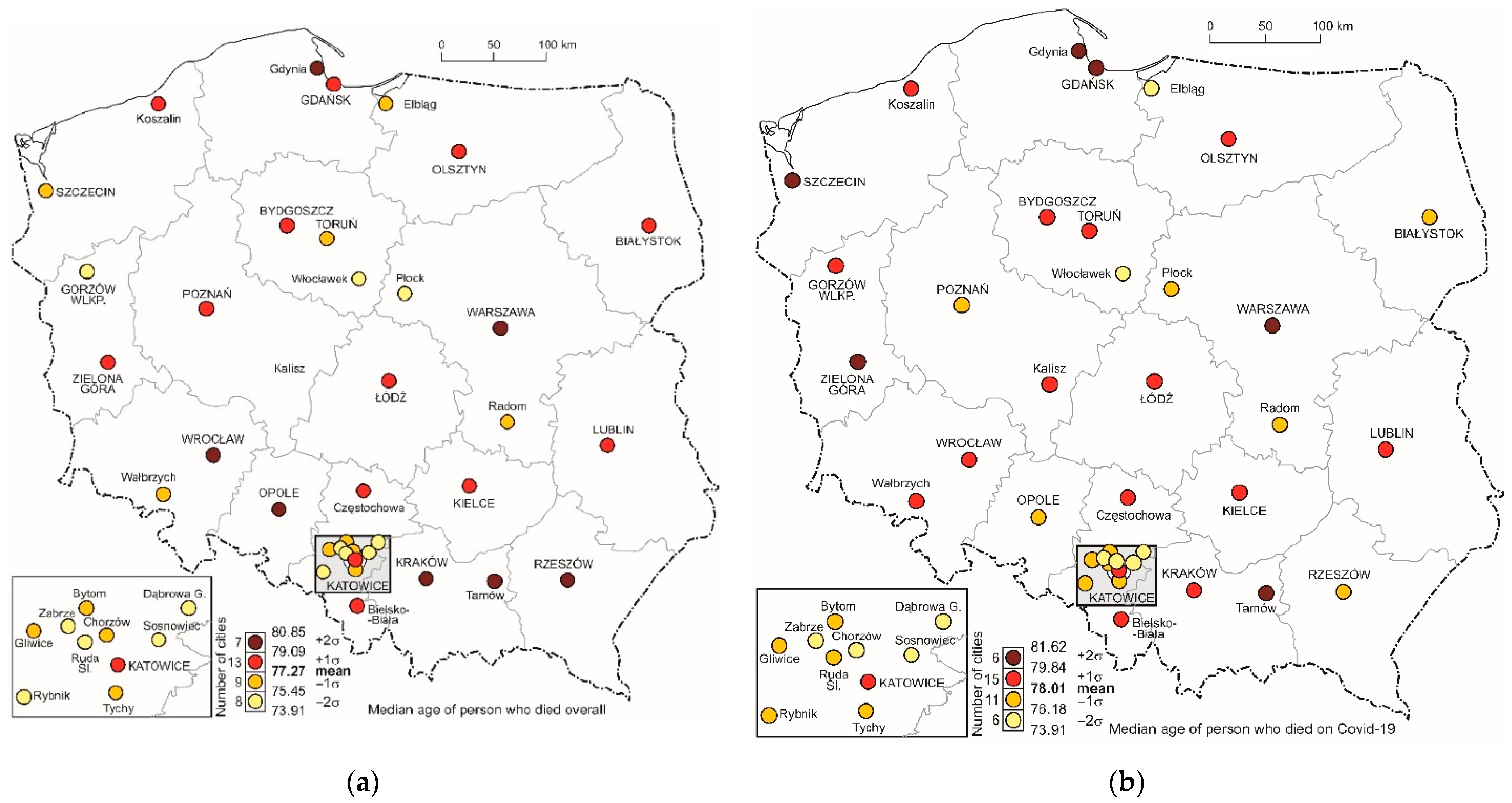

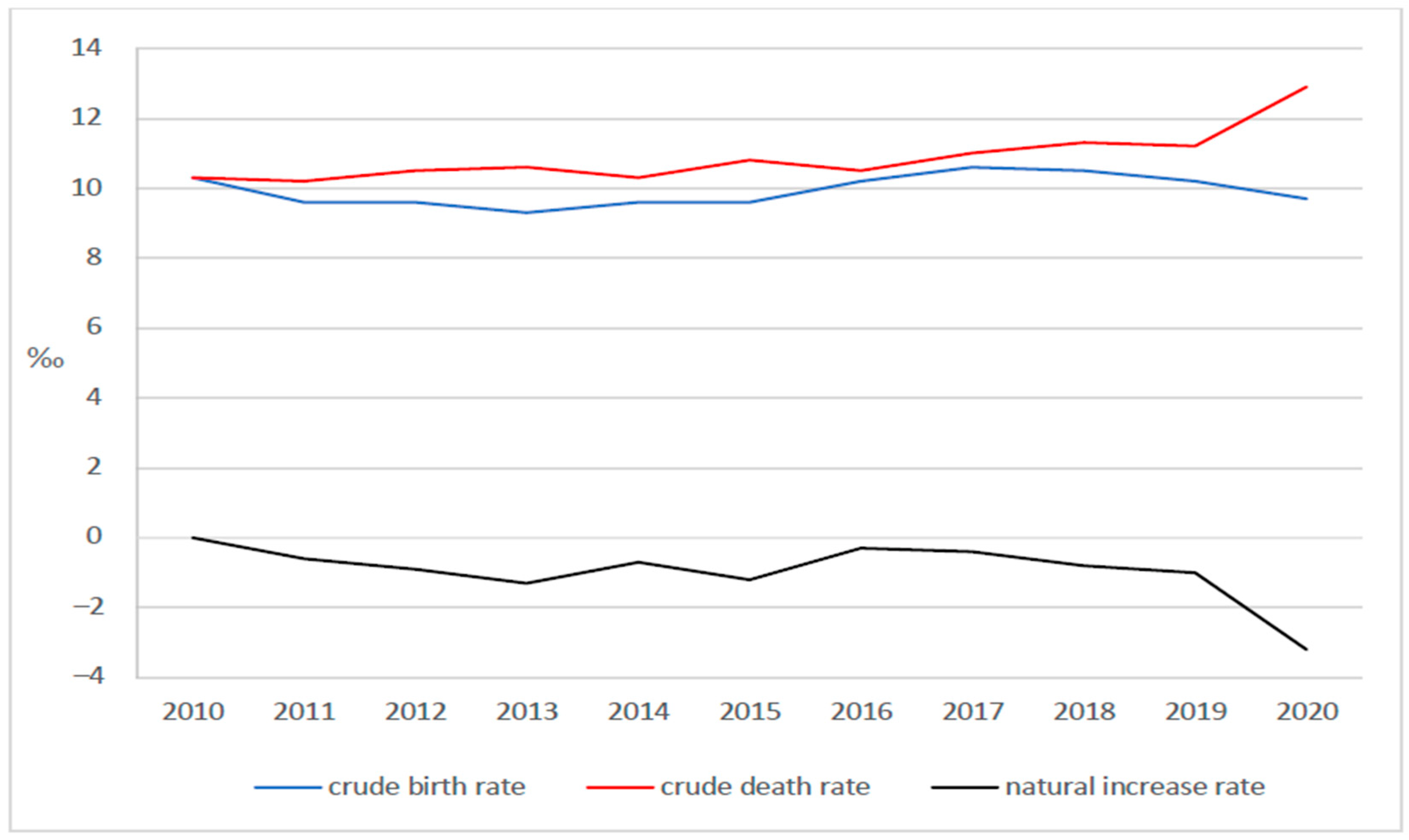

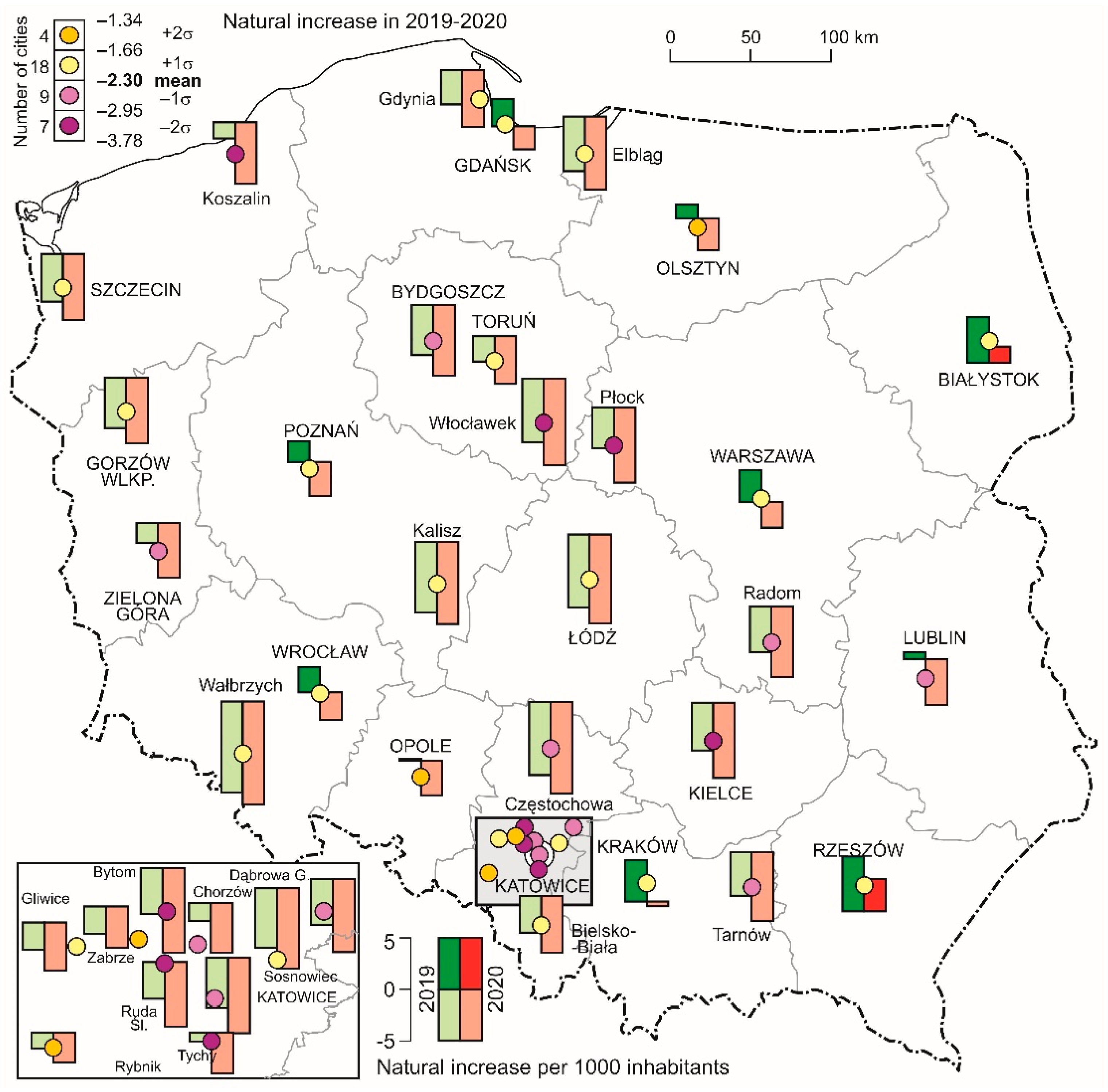

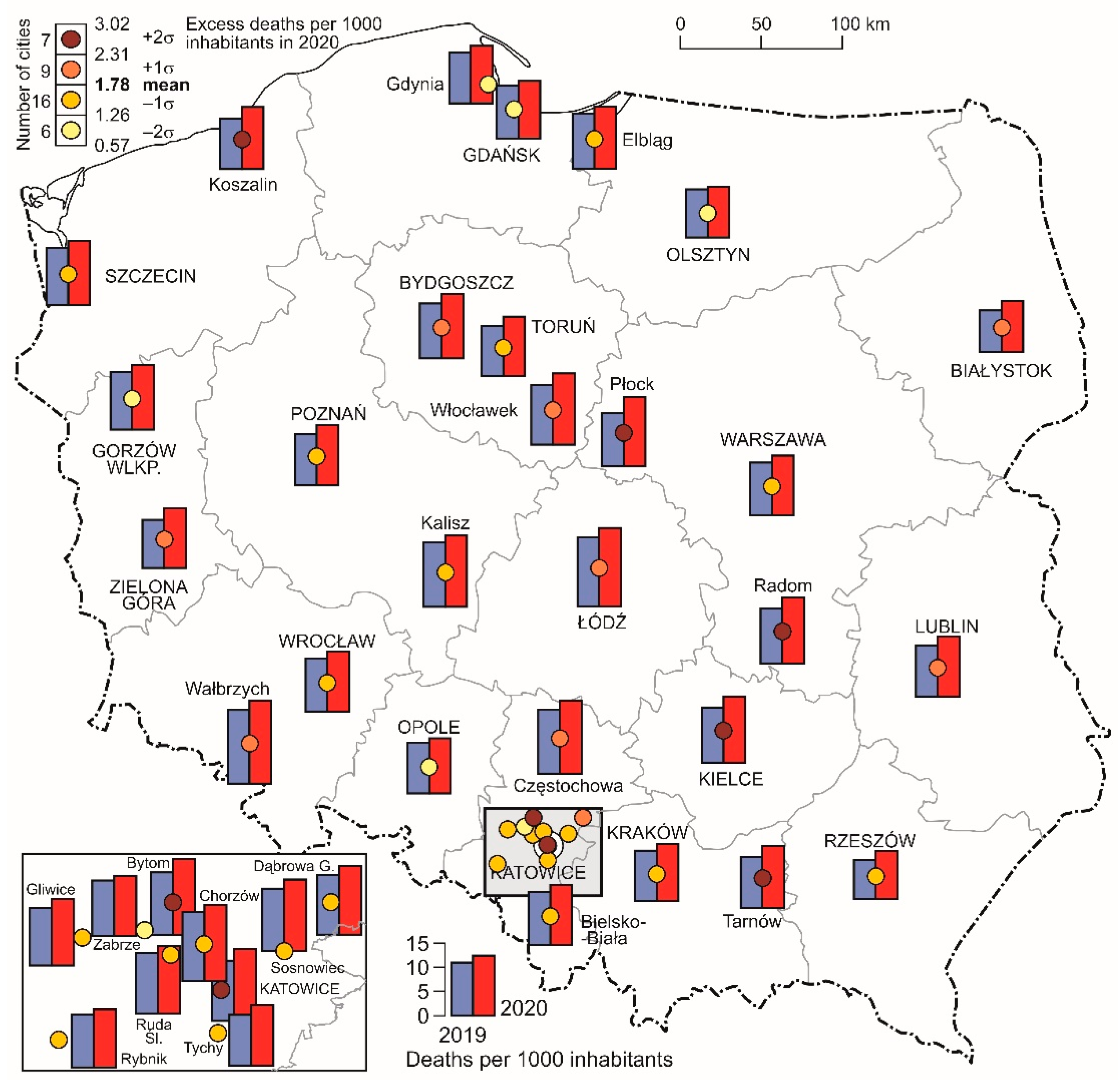

3.1. COVID-19 Deaths in Cities

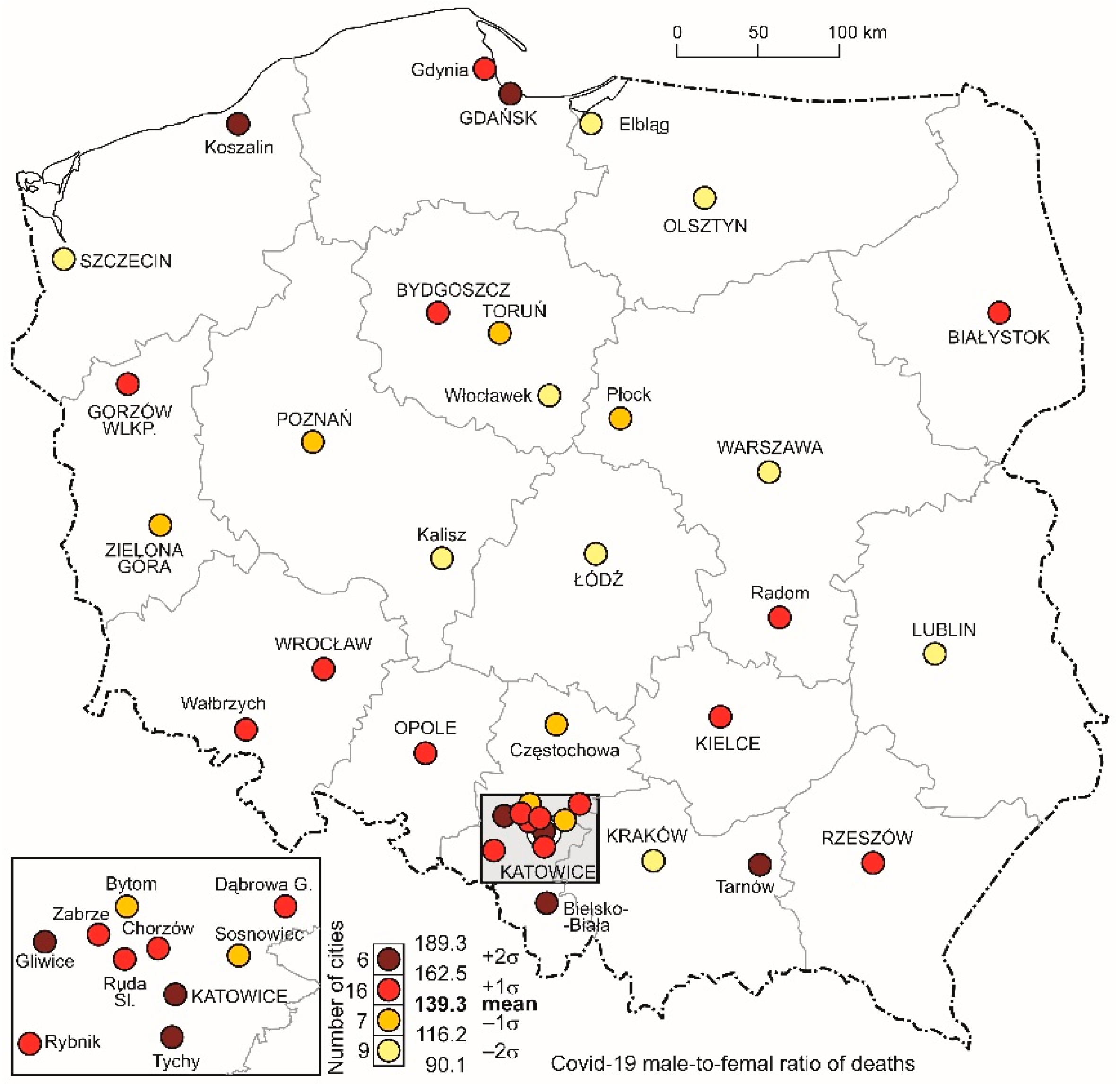

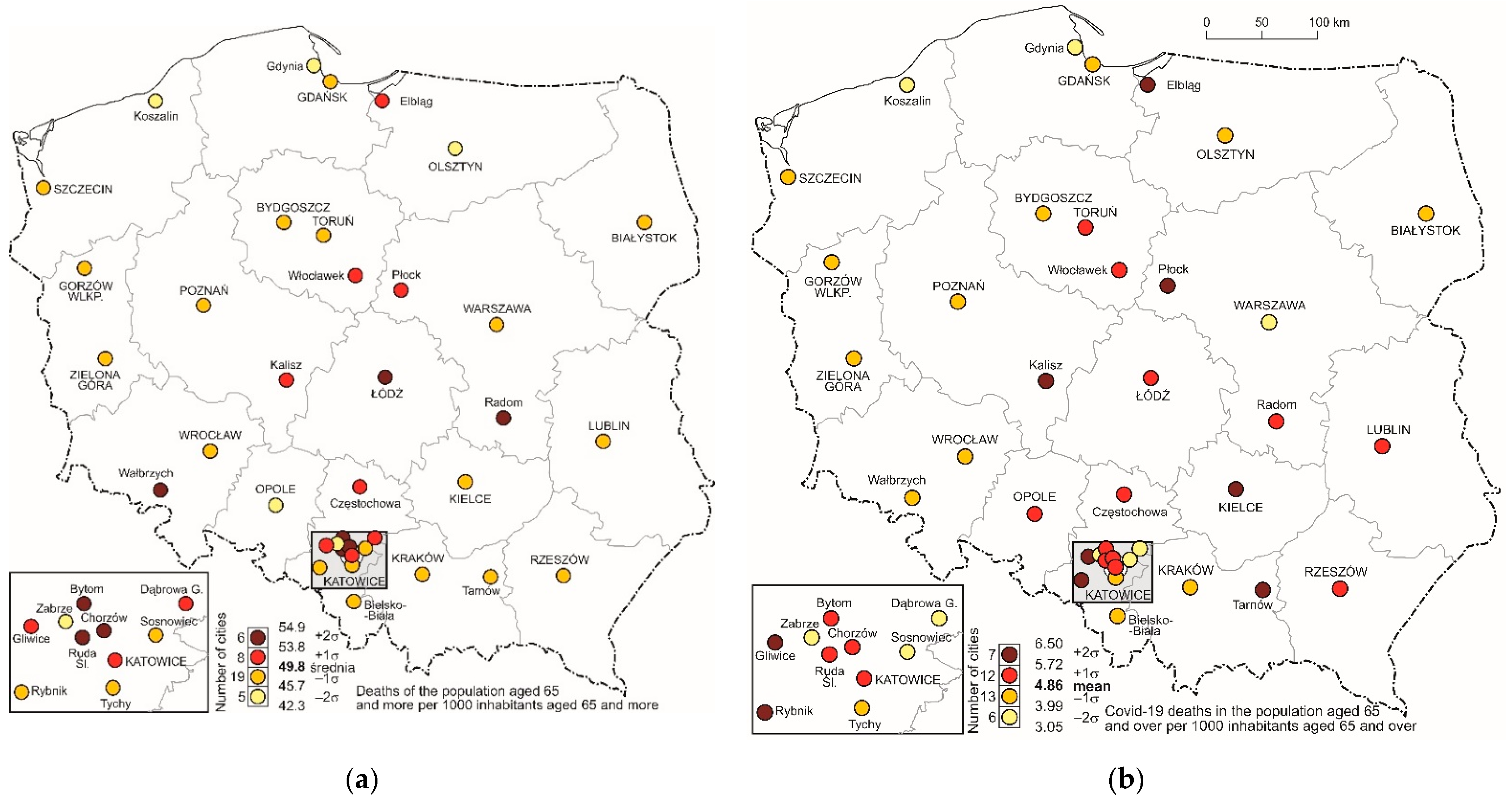

3.2. Structure of Deaths by Sex and Age

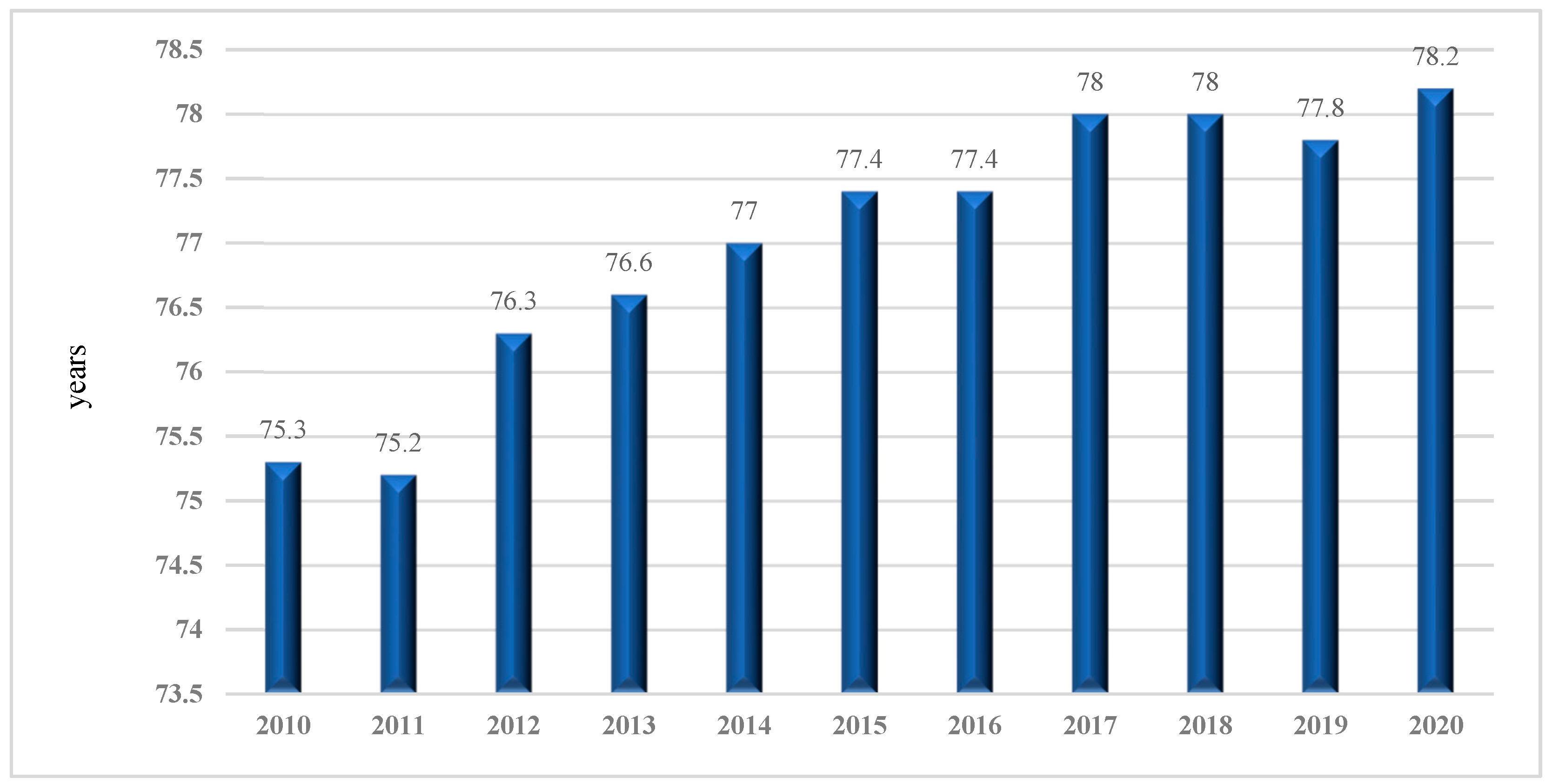

3.3. Demographic Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic—Selected Aspects

- a systematic increase in life expectancy values, reaching 80–85 years, and even higher for women;

- a decline in mortality due to cardiovascular diseases, which is mainly associated with medical progress and changes in lifestyle, although cardiovascular diseases and cancer remain the main causes of death;

- a large share of elderly people in the population structure;

- the emergence of new diseases, including those caused by viruses, e.g., HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B and C, Ebola virus, various types of hemorrhagic fever, as well as new bacterial diseases or the re-emergence of already existing diseases, e.g., cholera, malaria, dengue fever, diphtheria, and tuberculosis.

4. Perceptions of the COVID-19 Pandemic among Residents of Cities in Poland

4.1. Life Satisfaction by Place of Residence

“On 24 March 2020 Poland’s government announced further restrictions on people leaving their homes and on public gatherings. The new limits constrained gatherings by default to a maximum of two people (with an exception for families); an exception for religious gatherings, such as mass in the Catholic Church, funerals and marriages in which five participants and the person conducting the ceremony were allowed to gather; and an exception for work places. Non-essential travel was prohibited, with the exception of travelling to work or home (…) On 31 March 2020 the prime minister announced that Poland would strengthen the restrictions (…) According to the regulation, minors were prohibited from leaving their homes unaccompanied by a legal guardian. Parks, boulevards and beaches were closed, as well as all hairdressers, beauty parlors and tattoo and piercing salons. Hotels were allowed to operate only if they had residents in quarantine, in another form of isolation, on an obligatory work delegation for services such as building construction or medical purposes. Individuals walking in public were obliged to be separated by at least two meters, with the exception of guardians of children under 13 and disabled persons.”[49]

4.2. Fear and Concerns about the Pandemic

“residents of the largest cities are worse off than rural residents about not being able to move freely and having to stay at home (51% vs. 44%). They are also more frustrated by lack of physical activity (30% vs. 25%). They are more likely to feel lonely than residents of rural areas (43% vs. 33% among residents of rural areas), which they may compensate for by eating more often (24% in major cities vs. 18% in rural areas) and drinking alcohol (15% vs. 8% in rural areas). At the same time, residents of the largest cities, compared to residents of rural areas, spend more time sleeping and resting (33% vs. 21% in rural areas) and also read more books than before (31% vs. 20%).”([23], pp. 13–14).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

“Instead, all authorities are doomed to failure when they insist on coordinating society through the use of power and coercive commands. And this is perhaps the most important message that economic theory has to send to society: problems invariably arise from the use of coercive state power, no matter how well a given politician performs.”[58]

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, M.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.O.; Lee, S.; Park, I.K.; Park, J.; Seo, I. COVID-19 impact on city and region: What’s next after lockdown? Int. J. Urban Sci. 2020, 24, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesman, D.; Glazer, N.; Denney, R. The Lonely Crowd: A study of the Changing American Character; Yale Univ. Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1950; (reprinted in 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K. Moral Panics; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bagus, P.; Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. COVID-19 and the Political Economy of Mass Hysteria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florida, R.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Cities in a post-COVID world. Urban Stud. 2021. onlineFirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, M. The city and the virus. Urban Stud. 2021. onlineFirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.; Short, J.R. The Pandemic City: Urban Issues in the Time of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, H. Pandemie w historii świata. Wieś Rol. 2020, 188, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Alirol, E.; Getaz, L.; Stoll, B.; Chappuis, F.; Loutan, L. Urbanisation and infectious diseases in a globalised world. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.Y.; Webster, C.; Kumari, S.; Sarkar, C. The nature of cities and the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 46, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Sarkar, K. Impact of population density on COVID-19 infected and mortality rate in India. Modeling Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 7, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badora, B. Obawy Polaków w Czasach Epidemii (Fears during the Pandemic); CBOS Research Reports: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; p. 155. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Rungcharoenkitkul, P. Macroeconomic effects of COVID-19: A mid-term review. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2021, 26, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, A.; Gray, D.; Islam, A.; Bhuiyan, S. A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. J. Econ. Surv. 2021, 35, 1007–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papyrakis, E. (Ed.) COVID-19 and International Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin, J.; Hałasiewicz, A. (Eds.) Polska Wieś 2020; Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for Coding Deaths Related to the Epidemic Coronavirus Causing COVID-19 (as of 01.04.2020). Available online: www.pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/wytyczne-do-karty-zgonu-01.04.2020-1.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- List of Coronavirus Infections. Available online: www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus/wykaz-zarazen-koronawirusem-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; Chapter 2: The Health Impact of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/b0118fae-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/b0118fae-en (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Halik, R. Public Communication. Available online: https://businessinsider.com.pl/wiadomosci/dziwne-rozbieznosci-w-danych-o-zgonach-na-covid-19-region-regionowi-nierowny/qdrsy0w (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Zgony Według Płci Osób Zmarłych, Przyczyn Zgonów, Województw I Powiatów, (Deaths by Sex of Deceased, Causes of Death, Provinces and Districts) 2020: GUS. Available online: https://demografia.stat.gov.pl/BazaDemografia/Tables.aspx (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Feliksiak, M. Zadowolenie z Życia (Life Satisfaction); CBOS Research Reports: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; p. 5. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Cybulska, A.; Pankowski, K. Życie Codzienne w Czasach Zarazy (Everyday Life in the Time of Plague); CBOS Research Reports: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; p. 60. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Roguska, B. Obawy Przed Zarażeniem Koronawirusem i Postrzeganie Działań Rządu (Fear of Coronavirus and Evaluation of Government Actions); CBOS Research Reports: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; p. 141. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Badora, B. Wartości w Czasach Zarazy (Values in the Times of the Plague); CBOS Research Reports: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; p. 160. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Staszyńska, M. Zadowolenie z Życia (Life Satisfaction); CBOS Research Reports: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; p. 8. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Omyła-Rudzka, M. Koronawirus–Obawy, Stosunek Do Szczepień, Ocena Polityki Rządu (Coronavirus–Fears, Attitude towards Vaccination, Evaluation of Government Policy); CBOS Research Reports: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; p. 12. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Cofta Sz Domagała, A.; Dubas-Jakóbczyk, K.; Gerber, P.; Golinowska, S.; Haber, M.; Kolek, R.; Sokołowski, A.; Sowada, C.; Więckowska, B. Szpitale w Czasie Pandemii i Po Jej Zakończeniu. Available online: https://oees.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Alert-zdrowotny_2.pdf) (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- State of Health in the EU: Poland-Country Health Profile. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/publications/poland-country-health-profile-2021-e836525a-en.htm (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Garza, A. The Aging Population: The Increasing Effects on Health Care. Pharm. Times 2016, 82, 36–41. Available online: https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/the-aging-population-the-increasing-effects-on-health-care (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- COVID-19: Vulnerable and High Risk Groups. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/information/high-risk-groups (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Róży, A.; Chorostowska-Wynimko, J. Układ Immunologiczny Osób Starszych, The Immune System in the Elderly. 2017. Available online: http://alergia.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Uk%C5%82ad-immunologiczny-os%C3%B3b-starszych.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Olshansky, S.J.; Ault, B. The Fourth Stage of the Epidemiologic Transition: The Age of delayed Degenerative Diseases. Milbank Q. 1986, 64, 355–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rogers, R.; Hackenberg, R. Extending Epidemiologic Transition Theory: A New Stage. Soc. Biol. 1987, 34, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olshansky, S.J.; Carnes, B.A.; Rogers, R.G.; Smith, L. Emerging infection diseases: The Fifth Stage of the Epidemiologic Transition? World Health Stat. Q. 1998, 51, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Omran, A.R. The Epidemiologic Transition Theory revisited thirty years later. World Health Stat. Q. 1998, 51, 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Vallin, J.; Meslé, F. Convergences and divergences in mortality. A new approach to health transition. Demogr. Res. 2004, 16, 11–44. Available online: https://www.demographic-research.org/special/2/2/s2-2.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, W. Teoria przejścia epidemiologicznego oraz fakty na przełomie wieków w Polsce. Studia Demogr. 2009, 1, s.110–s.159. [Google Scholar]

- Prognoza Dla Powiatów i Miast Na Prawie Powiatu Oraz Podregionów Na Lata 2014–2050 (Opracowana w 2014). Statistics Poland. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/prognoza-ludnosci/ (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Szukalski, P. Starzenie się Ludności Miast Wojewódzkich–Przeszłość, Teraźniejszość, Przyszłość. Demogr. Gerontol. Społeczna–Biul. Inf. 2017, 12. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11089/24279 (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Janiszewska, A. Starzenie się ludności w polskich miastach. Space Soc. Econ. 2019, 29, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, T. Umieralność w ośrodkach wojewódzkich. In Ośrodki Wojewódzkie w Polsce-Ujęcie Alternatywne; Dutkowski, M., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego: Szczecin, Poland, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Szymański, F. Public Communication. Available online: https://pzn.org.pl/czym-jest-dlug-zdrowotny-i-co-mozna-z-nim-zrobic/ (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Kapitał Zdrowia 2020. Pandemia: Punkt Zwrotny dla Benefitów Pracowniczych. Report (in Polish), Prepared by Polskie Stowarzyszenie HR. Available online: https://hrstowarzyszenie.pl/kapital-zdrowia/ (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Basiukiewicz, P. Ani Jednej Łzy. Ochrona Zdrowia w Pandemii; Warsaw Enterprise Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Informacja o Zgonach w 2020 Roku (Death Information in 2020). 2021; Ministerstwo Zdrowia. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/489b7a0b-a616-4231-94c7-281c41d3aa30 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Kłos-Adamkiewicz, Z.; Gutowski, P. The Outbreak of COVID-19 Pandemic in Relation to Sense of Safety and Mobility Changes in Public Transport Using the Example of Warsaw. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_in_Poland (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Świtała, M. Wpływ Pandemii COVID-19 na Codzienną Mobilność Mieszkańców Warszawy. Gospod. Mater. Logistyka 2021, 9, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgórska, B. Zmiany przestrzenne w miastach wywołane pandemią COVID-19 a przestrzenny wymiar rewitalizacji. In Miasta XXI Wieku–Wybrane Zagadnienia; Hyrlik, A., Dylewski, D., Traczyk, S., Eds.; Archaegraph: Łódź, Poland, 2021; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gawrych, M.; Cichoń, E.; Kiejna, A. COVID-19 pandemic fear, life satisfaction and mental health at the initial stage of the pandemic in the largest cities in Poland. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dymecka, J.; Gerymski, R.; Machnik-Czerwik, A.; Derbis, R.; Bidzan, M. Fear of COVID-19 and Life Satisfaction: The Role of the Health-Related Hardiness and Sense of Coherence. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 712103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccination Coverage in Polish Municipalities. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/szczepienia-gmin#/poziomwyszczepienia (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Cieślińska, B.; Dziekońska, M. The Ideal and the Real Dimensions of the European Migration Crisis. The Polish Perspective. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Sustainable Development Goals Report. 2019. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/#sdg-goals (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Huerta de Soto, J. The Economic Effects of Pandemics: An Austrian Analysis. 2021. Available online: https://mises.org/wire/economic-effects-pandemics-austrian-analysis (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Huerta de Soto, J.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Bagus, P. Principles of Monetary & Financial Sustainability and Wellbeing in a Post-COVID-19 World: The Crisis and Its Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, R. (Ed.) Przemiany Demograficzne Miast Polski. Wymiar Krajowy, Regionalny i Lokalny; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Kraków, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| City | Number of Excess Deaths | Share of COVID-19 Deaths in All Excess Deaths (%) | Excess Deaths per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warsaw | 3185 | 49 | 178 |

| Bialystok | 562 | 50 | 189 |

| Bielsko-Biała | 296 | 63 | 174 |

| Bydgoszcz | 791 | 53 | 230 |

| Bytom | 486 | 41 | 298 |

| Chorzów | 179 | 79 | 167 |

| Częstochowa | 457 | 68 | 210 |

| Dabrowa Górnicza | 263 | 40 | 223 |

| Elbląg | 201 | 84 | 169 |

| Gdansk | 670 | 66 | 142 |

| Gdynia | 277 | 76 | 113 |

| Gliwice | 388 | 67 | 219 |

| Gorzów Wielkopolski | 314 | 46 | 255 |

| Kalisz | 211 | 73 | 214 |

| Katowice | 688 | 54 | 236 |

| Kielce | 579 | 50 | 300 |

| Koszalin | 244 | 44 | 231 |

| Krakow | 1484 | 50 | 190 |

| Lublin | 783 | 57 | 231 |

| Łódź | 1063 | 97 | 158 |

| Olsztyn | 194 | 91 | 114 |

| Opole | 246 | 70 | 192 |

| Plock | 383 | 45 | 325 |

| Poznan | 872 | 67 | 164 |

| Radom | 518 | 51 | 248 |

| Ruda Śląska | 242 | 69 | 178 |

| Rybnik | 287 | 67 | 209 |

| Rzeszów | 453 | 47 | 230 |

| Sosnowiec | 295 | 61 | 149 |

| Szczecin | 744 | 60 | 187 |

| Tarnów | 310 | 52 | 290 |

| Torun | 471 | 53 | 237 |

| Tychy | 259 | 53 | 204 |

| Walbrzych | 259 | 47 | 235 |

| Wloclawek | 279 | 54 | 256 |

| Wrocław | 1026 | 68 | 160 |

| Zabrze | 217 | 67 | 127 |

| Zielona Góra | 382 | 42 | 271 |

| Place of Residence (Number of Inhabitants) | Are You Generally Satisfied with Your Place of Residence? | Number of Respondents | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied (%) | Moderately Satisfied (%) | Dissatisfied (%) | ||||||

| 2018 | 2021 | 2018 | 2021 | 2018 | 2021 | 2018 | 2021 | |

| Village | 85 | 83 | 12 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 367 | 434 |

| Town below 20,000 | 84 | 77 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 11 | 130 | 116 |

| 20,000–99,999 | 77 | 86 | 17 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 198 | 237 |

| 100,000–499,999 | 75 | 76 | 15 | 17 | 10 | 6 | 136 | 186 |

| 500,000 or more | 84 | 81 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 93 | 89 |

| Total | 81 | 82 | 14 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 924 | 1062 |

| Are You Generally Satisfied with: | Percentage of Positive Answers by Survey Date | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XII 2018 | XII 2019 | XII 2020 | XII 2021 | |

| career | 71 | 71 | 70 | 65 |

| material conditions (housing, equipment, etc.) | 67 | 67 | 65 | 62 |

| education, qualifications | 64 | 63 | 65 | 64 |

| state of your health | 60 | 60 | 61 | 58 |

| future prospects | 52 | 51 | 49 | 46 |

| income and financial situation | 35 | 36 | 37 | 30 |

| Place of Residence (Number of Inhabitants) | Are You Generally Satisfied with Your Prospects for the Future? | Number of Respondents | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied (%) | Moderately Satisfied (%) | Dissatisfied (%) | ||||||

| 2018 | 2021 | 2018 | 2021 | 2018 | 2021 | 2018 | 2021 | |

| Village | 50 | 47 | 32 | 29 | 10 | 14 | 365 | 433 |

| Town below 20,000 | 48 | 34 | 29 | 29 | 17 | 21 | 128 | 115 |

| 20,000–99,999 | 46 | 47 | 29 | 30 | 18 | 15 | 196 | 237 |

| 100,000–499,999 | 44 | 51 | 37 | 29 | 16 | 14 | 134 | 184 |

| 500,000 or more | 54 | 48 | 31 | 32 | 8 | 13 | 92 | 86 |

| Total | 48 | 46 | 32 | 30 | 13 | 15 | 916 | 1054 |

| Place of Residence (Number of Inhabitants) | Are You Personally Afraid of Coronavirus Infection? | Number of Respondents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, I Am Afraid (%) | No, I Am not Afraid (%) | |||||

| IV 2020 | I 2022 | IV 2020 | I 2022 | IV 2020 | I 2022 | |

| Village | 69 | 57 | 28 | 41 | 408 | 460 |

| Town below 20,000 | 78 | 62 | 20 | 39 | 91 | 126 |

| 20,000–99,999 | 65 | 59 | 31 | 40 | 200 | 269 |

| 100,000–499,999 | 67 | 60 | 31 | 40 | 172 | 174 |

| 500,000 or more | 74 | 54 | 24 | 46 | 128 | 95 |

| Total | 69 | 58 | 28 | 41 | 999 | 1125 |

| Place of Residence (Number of Inhabitants) | Are the Current Restrictions: | Number of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Too Much | suitable | Too Small | Hard to Say | ||

| Village | 24 | 45 | 22 | 9 | 417 |

| Town below 20,000 | 22 | 44 | 25 | 9 | 141 |

| 20,000–99,999 | 20 | 48 | 24 | 8 | 204 |

| 100,000–499,999 | 23 | 45 | 21 | 11 | 168 |

| 500,000 or more | 27 | 34 | 16 | 22 | 99 |

| Total | 23 | 45 | 22 | 10 | 1029 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cieślińska, B.; Janiszewska, A. Demographic and Social Dimension of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Cities: Excess Deaths and Residents’ Fears. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138194

Cieślińska B, Janiszewska A. Demographic and Social Dimension of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Cities: Excess Deaths and Residents’ Fears. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):8194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138194

Chicago/Turabian StyleCieślińska, Barbara, and Anna Janiszewska. 2022. "Demographic and Social Dimension of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Cities: Excess Deaths and Residents’ Fears" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 8194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138194

APA StyleCieślińska, B., & Janiszewska, A. (2022). Demographic and Social Dimension of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Cities: Excess Deaths and Residents’ Fears. Sustainability, 14(13), 8194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138194