Abstract

Retail is one of the defining elements of urban spaces. The study of commerce is largely based on its evolution and how it relates with urban environments. Currently, with the advent of mass tourism, there has been an adjustment in the commercial fabric of the area’s most sought after by tourists. Among these latter areas, the historical centers of commerce stand out. The first objective of this research is to analyze the modern evolution of the commercial fabric of Lisbon by comparing the city center with the rest of the city. For this goal, I use a quantitative approach through the quotient location for specific retail typologies. The results show dissimilarities that are associated with the geographical location of retail, which vary according to the different retail typologies being analyzed. The second goal is based on the assumption that the mere analysis of the evolution of the retail typologies is limited in the context of tourist cities. Considering this matter, a qualitative method (photo analysis, conceptually supported by the concept of authenticity) is used. The results show the usefulness of the concept of authenticity to apprehend and discuss how retail is reacting to the tourism industry, thereby contributing to the transformation of the city center into a leisure and entertainment destination.

1. Introduction

Retail is one of the distinct elements of urban spaces. This is not a novel assumption, as one can recognize the importance of retail spaces throughout history. Undeniably, if there is more than one reason for the foundation of several urban agglomerations [1], retail occupies its space as one of the elements that led not only to the basis, but also to the consolidation of urban centers and their vitality and viability [2]. Henceforth, considering that cities and other urban spaces are more than the concentration of jobs and housing places, and emerge as a social construction—in which, at different scales, people interact—retail must be seen as more than the economic activity established through the exchange of products and services. It is, thus, a part of the social construct that is produced in urban spaces. However, if retail exists in other places rather than urban environments, it is in these latter areas that retail better expresses itself. In addition, retail is endowed with significant dynamics [3,4]. This dynamism is attested to by the variety and evolution of retail formats [5], such as the antique predominance of open-air markets to the current brick-and-mortar retail that exists in the town centers and streets of cities—with a given defined hierarchical structure of commercial spaces (see Berry [6], for example)—or even in shopping centers, retail parks, or in other retail formats [7,8]. If it cannot be assumed that this connection is a novelty, insofar that the preponderant role of commerce in the formation and consolidation of urban agglomerations throughout history is recognized, the acceleration of urban transformation processes has made the city–commerce relationship even more evident over the last few decades.

Recently, tourism has emerged as a major force that shapes several touristic cities. In Lisbon, the case study of the current research, the rise of the tourism industry after the 2008 world economic crisis has been provoking a meaningful set of urban transformations in different dimensions [9,10]. Retail has been accompanying this change, adapting to the new touristic landscape of the city. In addition, most impacts are felt on the city center, mostly because, as in other cities, this is the area most searched by tourists. In fact, despite certain ‘natural’ variations, city centers seem to be the areas most entrenched with retail. For instance, as analyzed by Henderson [11] regarding the UK context, despite the strong retail decentralization that occurred in that country during the last decades of the 20th century, city centers recovered their importance in terms of retail investment—something still in force through the private–public support of business improvement districts [12]. Taking this into consideration, the main goal of this research is to analyze the evolution of the commercial fabric of Lisbon from the end of the last century to the present.

Two periods are considered for the present analysis. The first period I analyze is the evolution of retail between the 1990s and the end of the 2000s. This period delimits the phase in which the city assumes a greater polycentrism and in which the city center loses prominence in the context of the city and region in which it is inserted. For the analysis of this period, I considered data from 1995 and 2007 from local authorities. I carry out a quantitative analysis of the evolution of retail spaces in order to understand its evolution.

For the second period, I analyze the evolution of retail from the 2010s onwards. In this period, the functional loss of the city center was consolidated and is also characterized by the growing importance of tourism as a shaping force of the existing commercial fabric in the area. For the analysis of this period, I also use quantitative data, but the approach is mostly qualitative. This option is justified by the specificities that arise from the evolution of commerce in tourist cities, considering that it is increasingly difficult to analyze the evolution of this sector just by studying its tenant mix. In these tourist areas, commerce has more than just its traditional functional function, which consists of supplying the population with the products and services they need. On the contrary, retail spaces of a given retail typology that are used to cater to local residents can adapt their products and start supplying new clients, such as tourists. Thus, the current analysis of commerce in touristic cities based on the composition of the tenant mix is not appropriated, as it must take into account how a new commercial landscape is built to attract a new class of consumers, which is formed by tourists in search of leisure. Thus, given the discussion about the different perspectives of the concept of authenticity—objective, constructivist, and existential—the second goal of the research is to study the features that nowadays characterize the commercial fabric of the city and how it presents itself to costumers, in light of the pressure exerted by the tourism industry.

After this introductory section, Section 2 is devoted to the theoretical framework, which is divided into three subsections: ‘Retail change’, ‘Tourism, touristification, and retail’, and ‘Authenticity in retail’. In Section 3, the methodological framework is designed to support Section 4, which is devoted to the presentation of the results. In the first subsection, an analysis of the evolution of the retail sector between 1995 and 2007 is performed, which is directly oriented to address this research’s first objective. In the second subsection, the main public policies that fostered the current transformation of the city center are presented. In the third subsection, through the lens of the authenticity concept, the current evolution of the inner-city center is presented. Finally, in Section 5, considering the objectives of the research, the discussion and conclusion are elaborated.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Retail Change

Retail change has long been a privileged topic of interest for geographers and other urban scientists [13]. Especially after the 1950s, retail experienced a severe change across different levels. The appearance and dissemination of shopping centers as new shopping ‘cathedrals’ [14] provoked major readjustments in the urban retail systems of several cities, particularly with the loss of importance of the consolidated inner city as a traditional shopping destination. In addition, other retail formats—power centers [7], retail parks, and others [15]—further questioned the stability of a retail structure formed by a balanced set of brick-and-mortar stores in town centers of different levels. Changes in retail can be further discussed, considering the rise of importance—through processes of concentration—of large companies with internationalization strategies; the introduction of marketing strategies; the modification of the in-store interface with clients; and, of course, the ongoing revolution brought by e-commerce [16]. In this latter case, online retail has recently seen its importance reinforced with the worldwide restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. Ingrained in this reading about the changes in retail in the last few decades is also the emergence of consumption and its interconnection with the retail sector and cities [18,19,20,21]. Underlying this emergence of consumption, in what some call the Consumption or Consumer society [22,23,24], are the intertwined social, cultural, political, and economic processes that, as Carreras [25] discussed, makes consumption a concept broader than the concept of ‘Demand’, which is traditionally used in economics.

2.2. Tourism, Touristification, and Retail

In the last decade, new challenges emerged as the driving forces of some changes in retail have become associated with factors such as tourism. The tourism industry is one sector that is gaining preponderance with the advent and consolidation of globalization [26]. Recognized as a quick way to improve the economy of cities and other destinations, tourism has been on the political agenda of most decision-makers, as some argue that this sector “provides both direct and indirect effects to the economy, in terms of income, employment, and infrastructure, among others” [27]. However, some local agents, activists, and scientists claim that a growing number of destinations, such as cities but also nature-based destinations, are being negatively affected by tourism [28,29], especially because the affluence of tourists is higher in number than what the respective destination is able to cope with [30].

In the literature, this position can be seen under two different perspectives. First, what has been questioned is how the creation or adaptation of urban infrastructures to support the tourism industry is challenging the social sustainability of the places most pressured by tourism [31]. Second, some argue about the limits of the economic benefits of tourism [32]. For instance, Siano and Canale [33] (p. 7), on their macroeconomic analysis of Italian provinces, conclude that “an excessive level of specialization in tourism activities is detrimental for economic results”, especially when an area reaches an “overtourism status”. Others even addressed how tourism can be detrimental to the sustainability of the environment [34]. The tourism sector, thus, stands at the intersection where, on the one side, claims are made about the negativity of their impacts to some touristic destinations, and, on the other side, it is argued that tourism improves the economic standards of local communities or, as claimed by the Secretary-General of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Mr. Zurab Pololikashvili, “Our sector gives them the chance to make a living. To earn not just a wage, but also dignity and equality. Tourism jobs also empower people and provide a chance to have a stake in their own societies—often for the first time.” (https://www.unwto.org/management/zurab-pololikashvili, accessed on 15 May 2022). In the analysis of touristification, one of the major debates focuses on the redirection of part of the housing stock to temporary accommodations for the so-called ‘sharing economy’ platforms, such as Airbnb, which have been on the forefront of the discussion [35,36,37]. Consequently, a set of studies have been conducted to discuss the impacts of such developments. Among other conceptual frameworks, some researchers mobilize the concept of gentrification to explain such evolution [38], especially if one considers that sometimes this substitution of the temporality associated with the use of housing (from long- to short-term) validates the Neil Smith rent gap theory and occurs through the direct and indirect displacement of former citizens [39], usually with lower resources, and often leaves them with few options for where to move, which is an aspect that is particularly relevant because, as pointed by some authors [40,41,42], this type of process of gentrification can occur in association with an overall increase in the rent price in a wider area. Nevertheless, processes of touristification are complex. Barata-Salgueiro [9] identifies three major sectors affected by touristification. Besides the already identified housing sector, this author also enhances the impact on the public space and on retail, which is the current research subject that I will devote my attention to henceforth. Since early 2000, some studies have analyzed this subject, although there is a clearly growing trend in the last few years. First of which, it must be highlighted that the tangled relation between touristification, retail change, and, to some extent, gentrification, is not exclusive to touristic areas or even to Western countries and cities. For example, the research of Ryu et al. [43] is focused on the residential streets of Seoul. In addition, as discussed previously, retail change occurs over a long period of time [44]. What is in question in touristic cities is how that change evolves and how it is characterized. Retail gentrification, thus, appears as an underlying process that influences change in some areas, but I argue that it is insufficient to apprehend the breadth and peculiarities of such changes. This argument does not underestimate the use of the concept of gentrification in the analysis of how city centers evolved. Several authors have been mobilizing it to explain how a given commercial fabric is replaced by a new one, either through the direct or indirect displacement of older retailers [45,46], in processes that clearly show some resemblances in very dissimilar geographical contexts [47]—although provincial forms of retail gentrification are to be acknowledged [48].

The transformation of the city center or other areas from an area specialized in retail and services—from a functional perspective, in which the targeted population is the local inhabitants and residents in the region—to an area devoted to new uses focused on leisure and entertainment is recognized as one of the usual consequences of the contemporary evolution of those areas [49]. Zukin [50] identified the retail typologies of boutiques, cafes, and restaurants as triggers of the transformation of some New York neighborhoods. Under these conditions, the homogenization of the commercial fabric unveils one of the main elements of that evolution. For instance, Loda et al. [51] analyzes the growth of food-related businesses in the city center of Florence to meet the demand of tourists.

2.3. Authenticity in Retail

In addition to the homogenization of the commercial fabric with certain retail typologies mushrooming in touristified areas, the new retail outlets also resort to the specific elements that capture the authenticity of the respective area [52].

If retail is a sector prone to change, the characteristics of what is mutable are dependent on the temporal period that is analyzed; on the geographical features of the analyzed area where such changes are implemented; and on the driving forces that propelled its evolution. In touristic cities, there is a construction of a new consumption ambiance, in which retail plays an important role, with authenticity assuming a central role. Authenticity is widely used in tourism studies [53], being defined as “tourists’ enjoyment and perceptions of how genuine their experiences are” [54] (p. 2). For the current study, the concept of authenticity will be considered within three categories [55].

- Objective: In this perspective, certain objects possess an authenticity that is somehow immutable and intrinsic [54], or as mentioned by Zhang et al. [56], “Objective authenticity refers to the authenticity of originals or that which is recognized by authority”. This evaluation of an objective authentic place, product, craft, or other can be legitimized by an external entity, such as local authorities or other institutions [57].

- Constructivist: This category, like the previous, is based on objective objects [54]. Constructive authenticity refers to the tourists’ projection of the authenticity of toured objects [56]. It refers to the recognition that the objects of authenticity—whether it may be a heritage place, a product, or service—can hardly be seen as intact since their inception. This perspective takes into consideration that there is a construction or modification of the respective object, thus, being a social construction over time [52].

- Existential: Relates to the experience lived by tourists, such as the fulfillment, fun, and other feelings that one enjoyed when doing touristic activities [58], and, to some extent, connecting to phenomenology [59,60]. As Kirillova et al. [60] debates, this category is related to experience economy, stressing the importance of introducing the element of experience into the simple act of shopping.

As Moore et al. [61] (p. 4) note, these different approaches to authenticity co-exist in the same spatial–temporal rationale, thereby combining “practical attempts to align the material, social, and personal/existential aspects of life”. These authors further add that authentic experiences (existential) can take place whether the individual is facing an objective or constructivist object. In a strict sense, objective authenticity refers to the elements of the past that one recognizes as original from a certain period of time; constructive authenticity relates to how those elements were reshaped, improved, or adapted; and existential authenticity connects to how visitors appropriate those elements as a part of their experience. The threefold approach to authenticity possesses some points of connection with the Lefebvre [62] triad:

- Spatial practice (perceived space);

- Representations of space (conceptualized space);

- Representational space (lived space).

In the ‘Spatial practice’, Lefebvre [62] mentions that there is a deciphering of the space and also a slow production of it. Leary-Owhin [63] relates this perspective with the physical and material parts of the city. Given that, as noted by this latter author, this concept does not predicate a stationary position, but rather maintenance and redevelopment, it can be associated with both objective and constructivist authenticity. In the ‘Representations of space’, Lefebvre [62] (p. 38) refers to this as the “conceptualized space, the space of scientists, planners, urbanists, technocratic”. It is the conceived space, with norms and other more formal or rigorous instruments, thus linking it to a more rigorous understanding of objective authenticity. Lastly, the ‘Representational spaces’ are linked with the existential understanding of authenticity, which is particularly evident when reading about how Lefebvre [62] (p. 39) feels about this representational and lived space: “It overlays physical space, making symbolic use of its objects […] to tend towards more or less coherent systems of non-verbal symbols and signs’’. Leary-Owhin [63] (p. 8) also corroborates this rationale when they refer to this last concept of the Lefebvre triad as an “urban everyday space as directly lived by inhabitants and users in ways informed not so much by representations of space as by associated cultural memory, images, and symbols imbued with cultural meaning”.

3. Materials and Methods

This research is supported by a mix-method involving quantitative and qualitative approaches. A quantitative approach will be followed for the period of 1995-2007, in which I resort to an available dataset from the Lisbon City Council that contains information about the commercial fabric that existed in Lisbon in those years. This latter year is prior to the profound transformation that occurred through tourism, being, therefore, useful to characterize the area. For this 1995–2007 period, the analysis will be based not only on the size of the commercial fabric and its variation, but also based on the location quotient for three retail typologies. The formula for the location quotient is as follows:

LQ = (Yij/Yj)/(Yi/Y), in which:

Yij = number of retail outlets from a certain retail typology in the analyzed area

Yj = total number of retail outlets in the analyzed area

Yi = number of retail outlets from a certain retail typology in Lisbon municipality

Y = total number of retail outlets in Lisbon municipality

Overall, the following maps were prepared:

- Total of retail outlets in the year 1995

- Total of retail outlets in the year 2007

- Absolute variation in the number of retail outlets, between 1995 and 2007

- Relative variation in the number of retail outlets, between 1995 and 2007

- Density of retail outlets in 1995

- Density of retail outlets in 2007

- Location quotient for HORECA sector in 1995

- Location quotient for HORECA sector in 2007

- Location quotient for Personal items sector in 1995

- Location quotient for Personal items sector in 2007

- Location quotient for Food retail sector in 1995

- Location quotient for Food retail sector in 2007

These twelve maps correspond to six different analyses, three of which are related to an overview of the evolution of retail in Lisbon (maps 1 to 6). The remaining three (maps 7 to 12) relate to the application of the location quotient to specific retail typologies, which are representative of the traditional evolution of a city center that is more focused on leisure and consumption—namely HORECA, personal items, and food retail. HORECA is a retail typology, whose acronym derives from the initial letters of hotels, restaurants, and cafes. Some relevant literature, such as Gotham [49], attests to its relevance in the context of the adaptation of certain areas to the tourism industry, which are associated with leisure. The personal items sector is the most representative of town centers with a certain importance in terms of shopping destinations. It fits Guy’s [64] classification of comparison shopping, as the shopping of clothing, footwear, personal accessories, and other similar products are strongly linked with shopping trips done with relatives and friends—thus, being leisure associated. Lastly, food retail is the sector that is clearly linked with a convenience stance, i.e., it has a more functional purpose, from the perspective of those who frequent these spaces. In this sense, the incorporation of the three sectors in the analysis will provide a comprehensive overview of the changes that have occurred in the area. The maps are presented with the boundaries according to the local administrative boundaries of the municipal parishes as they were at the time to which the maps go back.

For the analysis of the period of 2010 onwards, quantitative data about the evolution of retail will also be presented, as well as visual information, through photographs taken by the author. This visual information will be further discussed in Section 5, in which we resort to the theoretical framework to interpret it.

On his consideration of Lefebvre’s work, Leary-Owhin [65] advocates for a series of mixed-methods, resorting to Kofman and Lebas [66] to postulate that the Lefebvre production of space approach should be read with a certain openness and that “research could be done based on observation, investigation of concrete reality, and historical analysis” [65] (p. 32). Field work, with the on-site observation of the commercial practices, was complemented with illustrative photos taken by the author, which were further decoded.

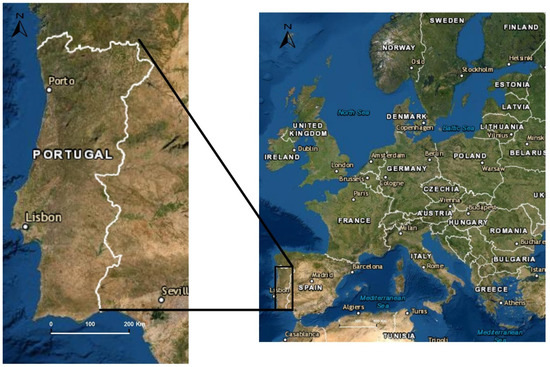

Lisbon is the selected case study for this research. It is the capital of Portugal, which is in the southwest of Europe (Figure 1). The metropolitan region is divided by the Tagus River, being that the city of Lisbon is located on the north bank of this river.

Figure 1.

Location of Lisbon in Portugal and in Europe.

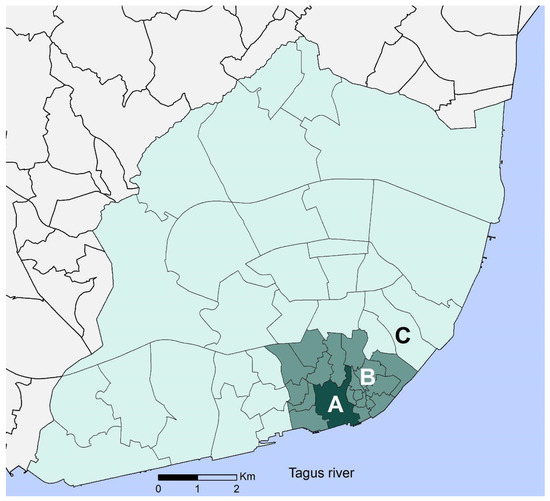

Its city center is an area strongly impacted by processes of touristification [10], as it is the area of the city most searched by tourists [67]. For the current analysis, the city will be divided into three areas. The first, marked with an ‘A’ in Figure 2, is the main city center, which is the historic main center of commerce and services of the city. The second area, marked with a ‘B’, is the extension of the inner city. Despite this, it may still be considered as the city center, though it is clearly detached from the area marked with ‘A’ because it is less attractive to tourists and, historically, the composition of its uses also differs. The third area, marked by ‘C’, encompasses the remaining areas of Lisbon municipality. It is in this latter area that the main residential neighborhoods of the city are located, alongside with some more specialized districts. Nevertheless, all three parts that compose the city are to be seen as consolidated urban areas.

Figure 2.

A: Lisbon major historic center. A: Main area of retail and services; B: Enlarged inner city; C: Other parts of the city.

4. Results

4.1. Act 1: Analyzing the Evolution of Lisbon City Center (1995–2007)

4.1.1. Total of Retail Outlets (1995–2007)

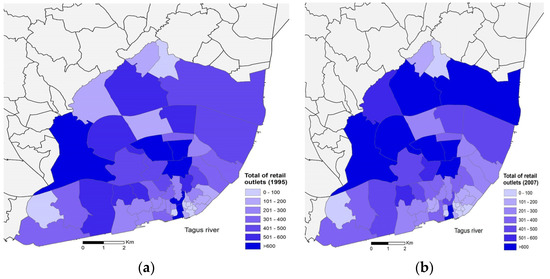

Figure 3 shows us a heterogeneous city in both analyzed years, with some areas of the city having a more robust offering of retail and services. It must, however, be stressed that the municipal parishes of the city center are small in size, which justifies that, in some of the inner-city municipal parishes, the total number of establishments is lower than that found in parishes further away from the center. Nevertheless, it is very perceptible that there is a meaningful concentration of retail spaces in this latter area. The second point to indicate is that this concentration is not homogeneous across all of the inner city. In fact, the only part of the city center that remained with the highest value between 1995 and 2007 is the one that belongs to the former municipal parish ‘São Nicolau’, which encompasses Augusta Street—the main and most symbolic high street of the area. In the surrounding area, especially to the east, on the hillside of the castle of São Jorge and in some of the neighborhoods that still have a relevant housing function, the total values of retail and services are lower.

Figure 3.

(a) Total of retail outlets in 1995; (b) Total of retail outlets in 2007.

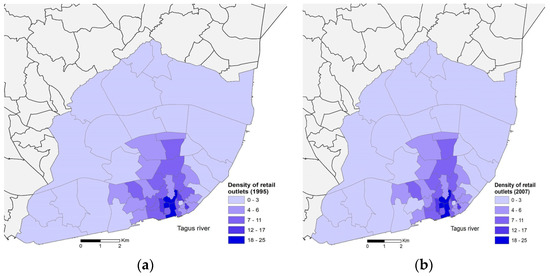

4.1.2. Density of Retail Outlets (1995–2007) (Outlets/Ha)

The concentration of retail and services and the dimension of the unit of analysis provides us the density of that sector in each municipal parish. When the effect of the absolute dimension of this last spatial unit is removed, Figure 4 is clear in showing the importance of the city center for commercial activities. Again, it is mainly the same axis stretching north from the river that possesses a higher value of density. Figure 4 validates and deepens the data from Figure 3, as the same areas in the surrounding areas have lower values. The remaining parts of the city possess what may be stated as a normal density of establishments.

Figure 4.

(a) Density of retail outlets in 1995; (b) Density of retail outlets in 2007.

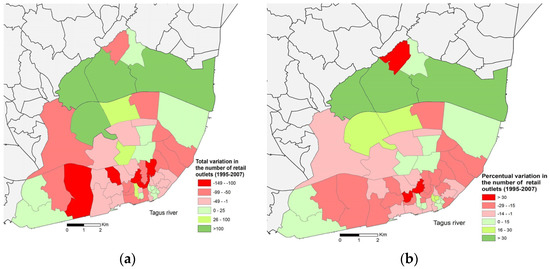

4.1.3. Variation in the Number of Retail Outlets (1995–2007)

Both previous figures attest to the geographical differences within Lisbon municipality. As a matter of fact, Figure 4 corroborates the initial division of the city into three main areas (see Figure 2) and confirms the relevance of the city center, which concerns the concentration of retail and services. It remains, however, to quantify the evolution of the retail sector in Lisbon. Figure 4 enlightens us about this subject. In absolute and relative numbers, one can see a decrease in some parts of the city center (Figure 5). This data is not a disclosure, as it corroborates the literature of the 1990s and early 2000s that highlighted the decline of the inner city. In this latter area, the parts in green, representing a positive evolution, is significant and related with the small dimension of the commercial areas, as previously analyzed in Figure 3.

Figure 5.

(a) Absolute variation in the number of retail outlets (1995–2007); (b) Relative variation in the number of retail outlets (1995–2007).

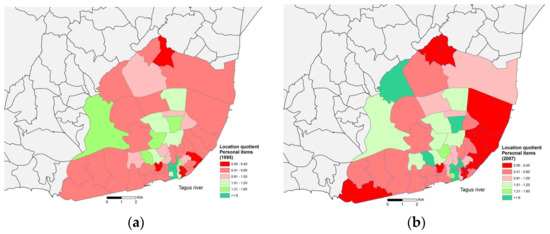

4.1.4. Location Quotient for the Retail Typology: “Personal Items”

As referred to in Section 3, there are some retail typologies that are prone to represent the functional decline of the city centers that can be traced to the analyzed period and its readjustment into a leisure and consumption destination. This typology is such an example and encompasses clothing, footwear, and leather goods retailers [64], as well as jewelry and other personal accessories. By interpreting Figure 6, it becomes easy to discern the over-representation of this type of business in the inner city in both analyzed years. In 2007, however, a location quotient of 1.6 or above was already visible in other parts of the city, which may indicate that, at that time, a process of urban hierarchical restructuring of the city was already established through new commercial centralities or through the consolidation of already existing ones.

Figure 6.

(a) Location quotient for the retail typology, “personal items in 1995”; (b) Location quotient for the retail typology, “personal items in 2007”.

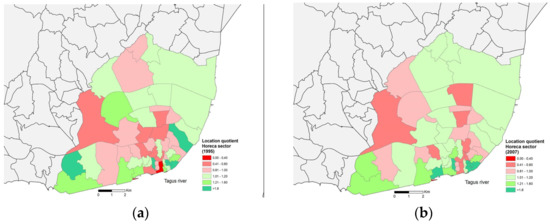

4.1.5. Location Quotient for the Retail Typology: “HORECA”

The HORECA retail typology incorporates retail outlets that prepare and serve food and beverages. It includes types of establishments from the hospitality industry. It is a significant sector—if not the most significant—that better reflects the transition of a given area to a leisure and consumption destination [52,67], which is often associated with the occupation of public space for the opening of terraces. Figure 7 shows that in 1995, this sector was under-represented in several parts of the inner city. In reading this figure in combination with Figure 6, it is confirmed that the city center in this year was very much characterized by still being a traditional shopping destination, especially for comparison shopping. Data from 2007 reflects a small adjustment, as the location quotient has a value between 0.41 and 0.80. The positive values (above 1) in the municipal parishes immediately to the east of the enlarged inner city are explained by the fact that they are neighborhoods with some residential vocation and, as such, have a set of cafes and restaurants that serve the local population. In addition, as they are traditionally tourist areas, some of the latter establishments also serve this floating population, often resorting to cultural elements, such as the ‘Fado’ musical genre.

Figure 7.

(a) Location quotient for the retail typology, “HORECA”, in 1995; (b) Location quotient for the retail typology, “HORECA”, in 2007.

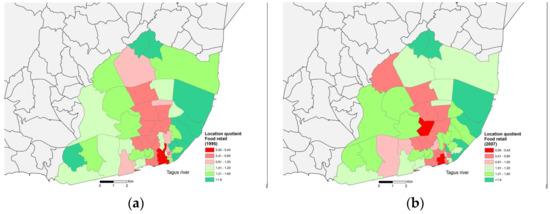

4.1.6. Location Quotient for the Retail Typology: “Food Retail”

The absence of establishments from this retail typology is common in the two analyzed years (Figure 8) that I sought to characterize in this text: In 1995, the modern and traditional city center, which was adjusted to a municipal or higher catchment area; and in 2007, where there was the transition to a contemporary leisure and consumption orientation. In both years, it is possible to visualize an axis that departs from the inner city to the north, which is formed around some avenues known as “New Avenues”—where a boulevard with luxury stores can be found, as well as the new Lisbon Central Business District. In general, in the other parts of the city in both the east and west of that axis, location quotients above 1 can be found, which coincide with residential neighborhoods and offer a greater variety of retail food outlets of different categories.

Figure 8.

(a) Location quotient for the retail typology, “Food retail”, in 1995; (b) Location quotient for the retail typology, “Food retail”, in 2007.

4.2. Act 2: Setting the Scene

In the second half of the decade that started in 2000, a set of intertwined measures paved the way for a drastic turnaround for the decline of the area. Although retail is a private activity, one is able to recognize the role of the central and local government in the reshaping of Lisbon inner city through a set of public policies. The first measure was the 2006 ‘New Regime of Urban Lease’ that introduced changes in the relation between retail tenants and landlords. In particular, it made the transfer of the right to use a particular commercial space more vulnerable by retailers who, before this revision of the legislation, could transfer their rights—as tenants—to new retailers who assumed the same rental conditions, thereby receiving in return a compensation value. With the entry into force of this new regime of urban lease, there was a 70% drop at the national level in the rate of transfers of those rights [68], encouraging traders whose commercial establishments were less profitable to abandon the spaces they occupied and increasing the rate of commercial rotation in areas with greater commercial vocations.

The second measure was the design of a proposal for the urban revitalization of the city center in 2006. One of the three key ideas of this proposal was to “achieve a relevant commercial and leisure function: Baixa-Chiado as a great historic but innovative center with a commercial and tourist vocation” [69]. Since part of the central area of the city was protected by legislation to safeguard the architectural characteristics of the buildings, this proposal, together with various urban planning instruments that made it effective, allowed certain reconstruction, rehabilitation, and requalification works to be carried, which led—in a short period of time—to the licensing of physical interventions in several buildings, thereby translating the beginning of the building rehabilitation and the overall revitalization and modernization of Lisbon city center [69]. The mentioned urban revitalization proposal was further reinforced in 2011 with the entry into force of a detailed land-use plan for the city center in 2011 [67].

The third element is related to the abrupt increase in the number of tourists, especially due to the growing importance of low-cost operators, but also due to the volume of tourists arriving in Lisbon via cruises. According to data from Deloitte [70], the number of guests in millions in the municipality of Lisbon went from 2374 in 2005, to 3114 in 2013, and 7216 in 2018. This means that not only was there a significant increase over a 13-year period, but also that the period of greatest intensity can be circumscribed between the years 2013 and 2018. Moreover, of the 7216 million guests, 2677 million (37%) stayed in local accommodations [70], which further reinforces the link between the growth of tourism and the processes of touristification—as already shown in other studies [10]. It is also important to highlight that this increase in the number of tourists and, inherently, the number of tourist infrastructures such as hotels, did not devalue the income obtained per tourist. In fact, the average income per room in hotels went from 45€ in 2005 to 89€ in 2018 [70].

4.3. Act 3: Retail and Authenticity in Lisbon City Center

The mentioned affluence of tourists to the city of Lisbon, and the recognized tourist preference to visit the main historical center of commerce and services of the city [71], inevitably provoked the readjustment of the commercial fabric of the area to serve these new passersby (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main features of the contemporary evolution of the commercial fabric in Lisbon inner city.

As the data from recent studies on the subject inform us (Table 1), as the transformation of the city center into a leisure destination consolidated, one can see the growing relevance of restaurants, cafes, and similar establishments. The effect on the landscape of the area is even more significant because the more robust presence of this type of establishment is accompanied by a larger occupation of public space through terraces. The decay of the retail typology, ‘personal goods’, is closely associated with the diminishing importance of the area as a strictly functional shopping destination, which is to the detriment of the already-mentioned leisure function. In this evolution, chain stores gained relevance, which were expectably attracted by the viability provided by the constant flow of tourists.

Although this analysis, through a quantifiable lens, provides us interesting information that allows for the assessment of the evolution of the commercial fabric and composition of the tenant mix, what has unfolded is that the possession of quantitative data about the evolution of commerce only partially explains the defining elements of the current commercial fabric of the inner city of Lisbon.

We need to resort to the concept of authenticity to further unfold how this adaptation of the commercial space is processed. As previously argued, there is a deliberate—and in different ways—use of the authenticity of the local culture, area, and space through the mobilization of a set of elements that Guimarães [31] designed as being ‘authentically Portuguese’, and whose reading must be seen as intertwined.

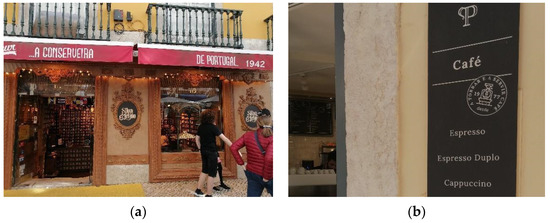

The first way to analyze this process can be framed in a dimension of ‘antiqueness’ that relates with how time provides an aura of trustworthiness to a given store. The first photo in Figure 9 shows a store that sells canned products, such as sardines. The year ‘1942’, which is shown on the awning of the establishment, does not refer to this store, but to the founding year the company that operates the commercial establishment—i.e., a Portuguese canning company located in a city north of the Lisbon metropolitan area. The representation of the year, thus, cannot be connected, either with this store specifically or with the location in the city center, but still projects a sense of historical relevance and experience in the production and selling of the product. The second store presented in Figure 9 is a coffee shop who advertises that it has been “roasting and serving coffee since 1977”. The reference to this year is also in one of the entrance doors. As in the previous example, it is not related to this store, but with the opening of the first store of the chain in the outskirts of Lisbon.

Figure 9.

(a) Example 1 of store using a time indication of opening; (b) Example 2 of store using a time indication of opening.

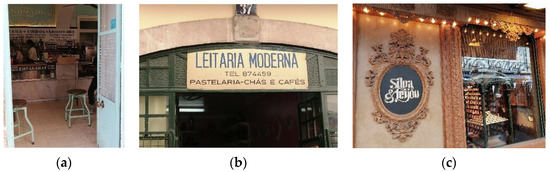

The second way to analyze the process is concerned with the appropriation of elements from previous uses in those stores, which somehow ignite the memory of the spaces and manipulate it for the current business. The images presented in Figure 10 are all representative of such an approach. In the first photo, a food and beverage store uses equipment/furniture from a previous occupation, namely a bakery shop. This deliberate use can both be seen in the indoor, in the counter, and in other furniture, as well as in the entrance, with the maintenance of the same elements of the façade. The second example is a common Portuguese café. The sign affixed by the current tenants of the space (since 2012) suggests the old use of the space that dates back to its origins in 1926. ‘Leitaria’ is a Portuguese term that refers to a space that sells milk and dairy products. The third photo is of the same establishment analyzed above (see Figure 9a). The maintenance of the designation ‘Silva e Feijóo’ intends to make the association with the former establishment that had this designation, and was located in the same space, using the reference to this previous store’s year of opening like it was theirs.

Figure 10.

(a–c) Example of stores using references and physical features from former occupations.

The third way to analyze the mobilization of elements of authenticity on the part of the commercial fabric is related to the use of products, crafts, and other tangible or immaterial elements of local culture or traditional modes of production. As exemplified in the images of Figure 11, this process may assume different forms. In the first photo, a store places an employee in the middle of the public space, referring to a way of artisanal production and associating it with the products that are sold in the store.

Figure 11.

(a–d) Example of stores that mobilize elements from the local culture (Note: in Figure 11a,c, people’s faces were blurred).

In the second photo, a restaurant whose current operation is recent (2018), uses elements of local culture in its name. The term ‘tasquinha’ or ‘tasca’ is the Portuguese designation for local workers’ taverns. Its use in this recent establishment, with a modern offer, intends, therefore, to refer to the somehow objective authenticity of those old spaces that, without much decoration, local workers used as social spaces. Using the same rationale, ‘Fado’ is a Portuguese musical genre that is linked with the traditional neighborhoods of Lisbon and has a deep bond with the local population.

The remaining two photos concern the use of Portuguese traditional products and the produced ambiance in which they are sold. Figure 11c is an old and traditional retail space—Camisaria Pitta—from the XIX century, which specialized in clothing sales, and whose recent closure gave place to the opening of a new retail store specialized in the selling of Portuguese custard tarts. On the one hand, this new establishment has kept much of the establishment’s external decor. Thus, it appropriates the recognition that the previous store had, distinguishing itself from new establishments by the objective authenticity it presents. On the other hand, it placed machinery in the interior space of the store—visually available to customers—thereby associating the confectionery in which it specializes to a handcrafted production mode. The procedure observed for this establishment is, to a large extent, similar to what occurs in a wide range of establishments—of which I highlight an establishment with a similar rationale—but which is dedicated to the sale of codfish cakes.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study I aimed to study the evolution of the commercial fabric of Lisbon inner city. The main historical center of Lisbon coincides with the area known to be the traditional center of commerce and services of the city. In the last decade, this part of the city has been particularly subject to pressure from the tourism industry, introducing a set of new dynamics of change. With this study, I did not aim to produce a particular critique of the changes occurring in Lisbon city center, but rather to interpret them.

The analysis of the maps shed some light on the relevance of the city center in terms of the concentration and density of retail activities. Despite this, there is a consensus on the decline of city centers in several Europeans cities in the last decades of the 20th century [72], in which Portuguese cities are to be included [73]. This research demonstrates that the city center in 1995 and 2007 still possessed a meaningful set of retail activities. I must recall that this decline of city centers is partially due to the rearrangement of urban retail systems, which are often associated with retail decentralization [74], namely with the opening of large shopping centers in peripheral locations. In Lisbon, the process was similar. Although with some delay, in comparison with countries such as the UK, regional shopping centers spread throughout the Lisbon region in the late 1990s and early 2000s [75]. Nevertheless, as attested by Figure 4 and despite the recognized decline of the city center in this period, Lisbon city center remained relevant, at least in terms of the concentration and density of retail activities. Furthermore, both maps on Figure 4 also show the permanence of a certain hierarchical structure in the retail system of Lisbon. This validates Barata-Salgueiro’s [76] statement that mentions that a hierarchical organization of retail in Portuguese cities remained valid, at that time, despite the development of the retail sector.

The hierarchical structure of the urban retail system of Lisbon is, to some extent, visible in all figures, although the analysis of the density of retail spaces (Figure 4) provides a clearer image of such structures. In the study of the density of retail spaces, the first axis composed of the main area for commerce and services stands out, followed by the second axis in a semi-circle, which is delimited to the south by the Tagus River where some of the city’s expansion axes to the north are visible. This visible hierarchy also validates the option taken for this research (Figure 2) by dividing the city into three mains axes, namely the main center of commerce and services, the enlarged central area, and the rest of the city.

Overall, during the period of 1995–2007, it is this transformation of the city and region into a more polycentric organization [76] that is captured in the remaining maps. Firstly, the absolute and percent variance of the number of outlets is in line with studies that show how the urban evolution of the city proceeds [77]. In a broader picture, the data demonstrate the loss of retail in the inner city, as well as the opposite evolution of the other less central areas of the city. Thus, this analysis should also consider the evolution that followed the urban development of Lisbon, an aspect particularly attested to by the increase of the commercial fabric in the eastern part of the city, which, among other reasons, is mainly due to the impacts of the urban transformation that took place in this part of the city during the time of the 1998 World Exposition [78].

The option for the location quotients for specific retail typologies also provides useful insights about the specificity of the city center and its respective evolution. The ‘personal items’ retail typology is one of the most representative of traditional and functional city centers. It fits into what Guy [64] assumes as comparison shopping. In modern times, especially before the dissemination of large shopping centers, this kind of retail space provided local populations with a shopping destination to go to with family or friends. In the main centers of commerce, the abundance of stores from this retail typology placed those areas on the top of the urban retail system hierarchy. In 1995 and 2007, Lisbon inner city possessed a concentration of this type of retail that was higher than the large part of the city, stressing its importance as a shopping destination. This was even more evident in 1995, when the inner-city municipal parishes had the highest value of the location quotient. In 2007, other municipal parishes obtained this highest value, complying with the retail decentralization as mentioned before.

The location quotient for the HORECA sector is the one that delivers less expected results. It is, nevertheless, helpful for the understanding of the current position of Lisbon inner city. The data illustrate an under-representation of the sector in 1995, which is connected with, at the time, the orientation of the area as a ‘more shopping than leisure destination’. In 2007, this under-representation was still visible in the inner city, although the gap was fading away. This undoubtedly demonstrates that the evolution that followed had tourism as a triggering factor, thereby corroborating studies on the impacts of tourism in Lisbon main city center [79]. This is substantiated not only indirectly through studies that place tourism as the main driver of the urban transformation of the city center in the last decade [10], but also directly through a set of studies that demonstrate the relevance of the HORECA sector in the current commercial landscape of Lisbon inner city [31,52,67].

In the current analysis, the location quotient of the food retail typology is useful to further characterize the city center. Most of the inner city is in the lowest value for the location quotient for this retail typology, representing a sharp absence of this type of store, which is in line with the features that characterize city centers. Food retail, resorting to Guy’s classification [64], fits into what this author designs as convenience shopping. Contrary to the aforementioned personal items sector, in which people often perform a comparison of different retail spaces and which can be done with a certain degree of leisure associated with that act, food retail is more straightforward, i.e., these types of stores are usually attended in proximity to where people live or work or in supermarkets or other retail formats in the outskirts. Leisure and conviviality are less associated with this retail typology. Thus, considering the small relevance of the city center, both for housing and also for work—this latter, especially due to the moving out of certain public and private offices—the low representation of the food retail sector in the city center is expected. Nevertheless, both maps on Figure 8 also show that municipal parishes to the west and east of the inner city still possess some expression of this retail typology, which links—in an inversely proportional way—to the aforementioned aspects, namely the fact that these areas still have some relevance as residential areas. This can be particularly important, as some authors claim that these areas, in neighborhoods such as Alfama or Mouraria, with the permanence of some residential functions, are currently the ones most pressured by the effects of touristification [31].

The second part of the empirical analysis, which was incorporated in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3, supports the unfolding of the process through which the city center is evolving and how it can be deciphered. On the one hand, it became clear that the current evolution of the commercial fabric can be framed. Given this matter, an overall consensus in what appears to be a stabilization of the tenant mix based on the rearrangement of the importance of certain retail typologies was found. This new commercial landscape has less establishments selling personal items and the opposite process with regard to cafes, restaurants, and similar spaces, thereby consolidating the area as a destination for leisure and consumption. The analyzed research indicates that the absolute number of outlets remained the same over a period that spread from a quarter of a century [31,52,67]. This means that the discourse of decline that characterized the area in the 1990s and early 2000s [80] may be misleading, insofar as, at this temporal distance, what has been happening since then is an adjustment for the area. That is, the area changed but continued to be relevant for commercial purposes.

On the other hand, for the analysis of this 2nd period based on previous works on the part of the author, there is an accumulated knowledge about the area that led to the postulation that the mere analysis of the evolution of retail typologies obscures the conceptual and applied richness that is brought to us by the various commercial establishments that exist in the area under study. Through a qualitative approach, I have identified some particularities in the commercial fabric of Lisbon inner city. Overall, it is recognizable that a use of elements previously identified as being related to the ‘authentically Portuguese’ [31], which were further divided into three main groups, represent different ways through which ‘authenticity’ is used by entrepreneurs in their retail outlets. Moreover, often in a given store, one can detect elements that can be framed in more than a group.

The first group includes establishments that have a specific reference to their opening year. This is a common feature in a wide number of outlets. The visibility given on the facade of the establishment to its opening year aims to associate the commercial space with a certain antiquity that legitimizes it as authentic. However, it is also possible to infer that this practice is, above all, notorious in establishments opened relatively recently, and that often the year displayed in the window is not related to the year of opening of that specific commercial space. This practice is associated with a constructivist posture of authenticity. It moves away from one of the perspectives that Zukin [81] assumed as being possible to have about authenticity, namely that something authentic can be understood as something new, not yet existing in a given context.

In the second group, the reference to elements from former establishments connects with objective authenticity. For instance, the display of the original wall of the building from the time it was built, which in the case of central Lisbon could mean a couple of hundred years, or the exhibit of a sign from a 1926 store, is a pastiche to what is seen as authentic from the area. Despite these elements and others, such as the recurrent use of furniture from old businesses that used to operate in the same commercial space, they do not have a formal recognition by a given authority of their originality, which would bring them closer to objective authenticity as understood by Zhan et al. [56] and Canavan & McCamley [57]; however, they do approach the museumified conception analyzed by Wang [55]. Under this understanding, those elements are displayed as if they were in a museum, thus, endowing them with an objective authenticity.

The third group also fits into this latter recurrence to objective authenticity, although it differs from the second group by being less material dependent—to the extent that it is in the intangibility of the used elements that one can find their added value. The direct allusion to intangible aspects such as Fado; to terms such as ‘tasca’, which refer to the lexicon of the popular classes; or to modes of production that refer to the past, is a mechanism to recreate objective authenticity. This is a way of reading the transformation of the area in line with the understanding of Xu et al. [82] (p. 1), which is that “tourist towns can also provide tourists with authentic experiences by offering a narrative about the past and present”. However, the mere act of modeling the built environment to adjust to the tourism certainly introduces this set of elements into the constructivist authenticity perspective.

Overall, if the subject of the homogenization of retail was previously approached in studies on retail change [83], within the transformation of the commercial ambiance of the city center for the tourism industry, the area became a stage for the tourists in search of unique experiences that fulfill their existential aspirations. As demonstrated by Zhang et al. [56], the use of local assets that fit the different dimensions of authenticity produce diverse but positive effects on the tourists’ experience.

This study shows that, despite the awareness that authenticity is explored in different tourist destinations, these specific elements are extremely locally rooted. Moreover, it is also the individual action of using the elements that are representative of local authenticity in each store that contributes to the broader construction of a new commercial ambiance in Lisbon city center. With this, I do not intend to claim that the conceptualization of the elements that were previously discussed are deliberately applied by entrepreneurs in a conceptual perspective. However, the analysis carried out and the extensive use of the various elements related to authenticity make it clear that their mobilization is part of routine business practices as a way of maximizing profit and that, in the midst of this extensive use, the area under analysis ends up being transformed.

As Zukin [84] noted, just the mere discourse of what is or is not authentic already refers to a space of representation, insofar as the native population of those places that are commercialized as authentic do not think of them as authentic. This understanding of Zukin [84] is obviously connected to the Lefebvre triad. When this latter author [62] (p.17) asked the question “to what extent may a space be read or decoded?”, he replied saying that an already produced space can be decoded—i.e., can be read—implying that a process of signification is developed. In Lisbon inner city and its commercial fabric, spatial practice is present in the reshaping of stores, producing new spaces for consumption, not only through terraces, but also through the commoditization of retail spaces. The mobilized elements of authenticity are, in this sense, tools for this production of space. This is connected with a larger trend for neoliberalization, which corroborates Queirós et al. [85] (p.261) when these authors say that “contemporary neoliberal dynamics impact not only the formal and physical production of space, but also its symbolic production through the consolidation of new behaviors and socialization practices”. Regarding the representations of space, or conceptualized space, I have also analyzed how the current ambiance of the inner city is not organic. Despite the proven external factors that contributed directly and indirectly to the current status [10], Lisbon inner city, as it currently presents itself, is the result of planners, politicians, and other decision-makers, in what can be framed as the Lefebvre [62] ‘Representations of space’ or conceptualized space. That is, the entry into force of legislation favoring the substitution of outlets in a period where the pressure from the tourism industry began to be felt demonstrates that the city center is as it was conceptualized to be. Lastly, the analyzed area is also a representational space. The decoding of the space, on the part of tourists, is done as part of their quest for existential authenticity. Of course, assuming tourists as the main users of the area seems appropriate, as the area is now mainly for leisure and even the locals that use it do not jeopardize the interpretation of the area as a representational space, thereby stressing “the importance of separating the authentic everyday life from that which has been masked by the encumbrances of capitalism” [86] (p. 137).

As a final remark, I must stress the complexity of the analysis of urban spaces and the growing interconnection of different factors that contribute to their change. As a result, urban studies find it increasingly difficult to observe and interpret a given territory in a comprehensive way.

Thus, this research claims for inclusive urban and tourism studies that bring more than the mere presentation of the positive and negative effects of tourism in urban spaces, arguing that, despite the importance of explaining these impacts, it is crucial to understand the processes that cause these impacts. At this point, I highlight the relevance of trying to understand how demand (tourists), supply (support infrastructure, including hotels, commerce, and services, among others), and the regulation and intervention of public authorities are connected and contribute to the evolution of touristic cities. Furthermore, for urban studies, this study highlights the relevance of taking into account the time scale. That is, when analyzing a period that extends for more than a quarter of a century—as I have done in this research—it is clear that the reading of the situation of a given urban space must be done with care, insofar as what is understood as negative at a given moment, may not be more than a transitional phase.

Thus, this study that I present here is not intended to be a point of arrival, but rather a small contribution to futures studies on the area analyzed.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project Sustainable urban requalification and vulnerable populations in the historical centre of Lisbon (PTDC/GESURB/28853/2017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kotkin, J. A Cidade—Uma História Global; Círculo de Leitores: Maia, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft, N. The vitality and viability of town centres. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 2533–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Cachinho, H. As relações cidade-comércio. Dinâmicas de evolução e modelos interpretativos. In Cidade e Comércio: A Rua na Perspectiva Internacional; Carreras, C., Pacheco, S., Eds.; Armazém das Letras: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009; pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, P. Shopping centres in decline: Analysis of demalling in Lisbon. Cities 2019, 87, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.; Sorenson, M.; Aversa, J. The geography of lifestyle center growth: The emergence of a retail cluster format in the United States. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B. Commercial Structure and Commercial Blight: Retail Patterns and Processes in the City of Chicago; Research Paper 85; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, T.; Simmons, J. Evolving retail landscapes: Power retail in Canada. The Canadian Geographer. Le Géographe Can. 2006, 50, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainback, K.; Ekl, E. The spread of “big box” retail firms and spatial stratification. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. Alojamentos turísticos em Lisboa. Scripta Nova 2017, 21, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Mendes, L.; Guimarães, P. Tourism and urban changes. Lessons from Lisbon. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, S. City centre retail development in England: Land assembly and business experiences of area change processes. Geoforum 2011, 42, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grail, J.; Mitton, C.; Ntounis, N.; Parker, C.; Quin, S.; Steadman, C.; Warnaby, G.; Cotterill, E.; Smith, D. Business improvement districts in the UK: A review and synthesis. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2020, 13, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Ntounis, N.; Millington, S.; Quin, S.; Castillo-Villar, F. Improving the vitality and viability of the UK High Street by 2020: Identifying priorities and a framework for action. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 310–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cachinho, H. O Comércio Retalhista Português: Pós-Modernidade, Consumidores e Espaço; GEPE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Astbury, G.; Thurstain-Goodwin, M. Measuring the Impact of Out-of-town Retail Development on Town Centre Retail Property in England and Wales. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2014, 7, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Livingstone, N. The ‘online high street’ or the high street online? The implications for the urban retail hierarchy. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2018, 28, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P. Uma avaliação preliminar da resiliência do tecido comercial de Portugal à pandemia do COVID-19. Rev. Bras. De Gestão E Desenvolv. Reg. 2020, 16, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachinho, H.; Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Guimarães, P. Comércio, Consumo e as Novas Formas de Governança Urbana; Centro de Estudos Geográficos, Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, M. Cities and Consumption; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pintaudi, S. Anotações sobre o espaço do comércio e do consumo. In Cidade e Comércio: A Rua Na Perspectiva Internacional; Carreras, C., Pacheco, S., Eds.; Armazém das Letras: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009; pp. 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sommella, R.; D’Alessandro, L. Retail Policies and Urban Change in Naples City Center: Challenges to Resilience and Sustainability from a Mediterranean City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D. Consumption and the City, Modern and Postmodern. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1997, 21, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, B.; Goodwin, N.; Nelson, J. Consumption and the Consumer Society, Tufts University: Somerville, United states of America. 2019. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/eci/files/2019/10/Consumption_and_Consumer_Society.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Wynne, D.; O′Connor, J.; Phillips, D. Consumption and the Postmodern City. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 841–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, C. For a more critical consumption history. In City, Retail and Consumption; D’Alessandro, L., Ed.; Universita Degli studi di Napoli: Naples, Italy, 2015; pp. 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Derudder, B.; Wang, F.; Shao, R. Geography and location selection of multinational tourism firms: Strategies for globalization. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, D.; Filis, G. Tourism demand and economic growth in Spain: New insights based on the yield curve. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Chee, J. Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1857–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kovacs, J. Arts-led revitalization, overtourism and community responses: Ihwa Mural Village, Seoul. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarchuka, O.; Barr, J.; Cozzio, C. How much is too much? Estimating tourism carrying capacity in urban context using sentiment analysis. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P. Retail change in a context of an overtourism city. The case of Lisbon. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 7, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S. Testing the Tourism-Led Growth hypothesis: The case of Malta. Acta Oeconomica 2009, 59, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, R.; Canale, R. Controversial effects of tourism on economic growth: A spatial analysis on Italian provincial data. Land Use Policy 2022, 117, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehigiamusoe, K. Tourism, growth and environment: Analysis of non-linear and moderating effects. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1174–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurran, N.; Zhang, Y.; Shrestha, P. ‘Pop-up’ tourism or ‘invasion’? Airbnb in coastal Australia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, K.; Merante, M. Is home sharing driving up rents? Evidence from Airbnb in Boston. J. Hous. Econ. 2017, 38, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Aurioles, B.; Tussyadiah, I. What Airbnb does to the housing market. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 90, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, E. Evaluating the impact of short-term rental regulations on Airbnb in New Orleans. Cities 2020, 104, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-López, M.; Jofre-Monseny, J.; Martínez-Mazza, R.; Segú, M. Do short-term rental platforms affect housing markets? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 119, 103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.E. Community consequences of airbnb. Wash. Law Rev. 2019, 94, 1577. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, S. Divergence in planning for affordable housing: A comparative analysis of England and Portugal. Prog. Plan. 2022, 156, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Hu, M. Spatial distribution of Airbnb and its influencing factors: A case study of Suzhou, China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 139, 102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Kim, D.; Park, J. Characteristics Analysis of commercial gentrification in Seoul focusing on the vitalization of streets in residential areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, R.; Thomas, C. Retail Change—Contemporary Issues; Routlegde: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, P. The Transformation of Retail Markets in Lisbon: An Analysis through the Lens of Retail Gentrification. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1450–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Waley, P. Traditional retail markets: The new gentrification frontier? Antipode 2013, 45, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delgadillo, V.; Niglio, O. Mercados de Abasto—Patrimonio, Turismo, Gentrificación; Aracne Editrice: Canterano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, G.; Dowling, R. Microgeographies of retailing and gentrification. Aust. Geogr. 2001, 32, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K. Tourism gentrification: The case of New Orleans Vieux Carré (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S.; Trulillo, V.; Frase, P.; Jackson, D.; Recuber, T.; Walker, A. New retail capital and neighborhood change: Boutiques and gentrification in New York city. City Community 2009, 8, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loda, M.; Bonati, S.; Puttilli, M. History to eat. The foodification of the historic centre of Florence. Cities 2020, 103, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P. Unfolding authenticity within retail gentrification in Mouraria, Lisbon. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2022, 20, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly, J. A review of authenticity research in tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 92, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Io, M.; Fátima, H.; Ngan, B.; Peralta, R. Understanding augmented reality marketing in world cultural heritage site, the lens of authenticity perspective. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, P.; Peng, Y. Effect of Commercialization on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Satisfaction in the Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: Case Study of Langzhong Ancient City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, B.; McCamley, C. Negotiating authenticity: Three modernities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. Existential authenticity and destination loyalty: Evidence from heritage tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The philosophical, ethical and theological groundings of tourism: An exploratory inquiry. J. Ecotourism 2018, 17, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. Tourism and Existential Transformation: An Empirical Investigation. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Buchmann, A.; Fisher, D. Authenticity in tourism theory and experience. Practically indispensable and theoretically mischievous? Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M. A Lefebvrian analysis of the production of glorious, gruesome public space in Manchester. Prog. Plan. 2013, 85, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, C. Classifications of retail stores and shopping centres: Some methodological issues. GeoJournal 1998, 45, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary-Owhin, M. Lefebvre’s transduction in a neoliberal epoch. In The Routldge Handbook of Henry Lefebvre, the City and Urban Society; Leary-Owhin, M., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routldge: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kofman, E.; Lebas, E. Writings on Cities: Henri Lefebvre; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Guimarães, P. Public Policy for Sustainability and Retail Resilience in Lisbon City Center. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idealista, Trespasses Comerciais Caíram 70% Devido à Nova Lei Das Rendas. 2011. Available online: https://www.idealista.pt/news/imobiliario/habitacao/2011/06/02/2845-trespasses-comerciais-cairam-70-devido-a-nova-lei-das-rendas (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Proposta de Plano de Pormenor de Salvaguarda da Baixa Pombalina; Câmara Municipal de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006; Available online: https://www.lisboa.pt/cidade/urbanismo/planeamento-urbano/planos-de-pormenor/detalhe/baixa-pombalina (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Deloitte. Estudo de Impacte Macroeconómico do Turismo na Cidade e na Região de Lisboa em 2018; Deloitte: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.visitlisboa.com/pt-pt/sobre-o-turismo-de-lisboa/d/599-estudo-de-impacte-do-turismo-2018-sintese/showcase (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Turismo de Lisboa. Inquérito às Atividades dos Turistas e Informação; Turismo de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; Available online: https://www.visitlisboa.com/pt-pt/sobre-o-turismo-de-lisboa/d/305-inq-as-actividades-dos-turistas-e-informacao/showcase (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Guy, C. Controlling New Retail Spaces: The Impress of Planning Policies in Western Europe. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 953–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J. Os projectos de urbanismo comercial e a revitalização do centro da cidade. Rev. Memória Em Rede 2012, 2, 76–89. Available online: https://periodicos.ufpel.edu.br/ojs2/index.php/Memoria/article/view/9514/6316 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Guy, C. Planning for Retail Development, A Critical View of the British Experience; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cachinho, H. O comércio retalhista: Da oferta de bens às experiências de vida. In Geografia de Portugal: Actividades económicas e espaço geográfico, Medeiros C. Coord.; Círculo dos Leitores: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006; pp. 264–331. [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T. Comércio e Cidade; Economia & Prospectiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 1998; Volume II, pp. 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, T.; Guimarães, P.; Cachinho, H. The role of shopping centres in the metropolization process in Fortaleza (Brazil) and Lisbon (Portugal). Hum. Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 14, 2067–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriere, J.; Demaziere, C. Urban planning and flagship development projects: Lessons from EXPO 98, Lisbon. Plan. Pract. Res. 2002, 17, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. Gentrificação turística em Lisboa: Neoliberalismo, financeirização e urbanismo austeritário em tempos de pós-crise capitalista 2008–2009. Cad. Metrop. 2017, 19, 479–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P. An evaluation of urban regeneration: The effectiveness of a retail-led project in Lisbon. Urban Res. Pract. 2017, 10, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Changing landscapes of power: Opulence and the urge for authenticity. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Le, T.; Kwek, A.; Wang, Y. Exploring cultural tourist towns: Does authenticity matter? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnaby, G. Look up! Retailing, historic architecture and city centre distinctiveness. Cities 2009, 26, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Consuming authenticity. Cult. Stud. 2008, 22, 724–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, M.; Ludovici, A.; Malheiros, J. The consequential geographies of the immigrant neighbourhood of Quinta do Mocho in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. In The Routledge Handbook on Henri Lefebvre, the City and Urban Society; Leary-Owhin, M., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Leung, H. Reading and applying Lefebvre as an urban social anthropologist. In The Routledge Handbook on Henri Lefebvre, the City and Urban Society; Leary-Owhin, M., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).