L2 Motivational Self System, International Posture and the Sustainable Development of L2 Proficiency in the COVID-19 Era: A Case of English Majors in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. L2 Motivational Self System

2.2. International Posture

2.3. The Relationships between L2MSS, International Posture and L2 Proficiency

- (1)

- In the COVID-19 era, what is the internal structure of L2MSS of English majors in China?

- (2)

- In the COVID-19 era, what are the relationships between L2MSS, international posture, and L2 proficiency of English majors in China?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

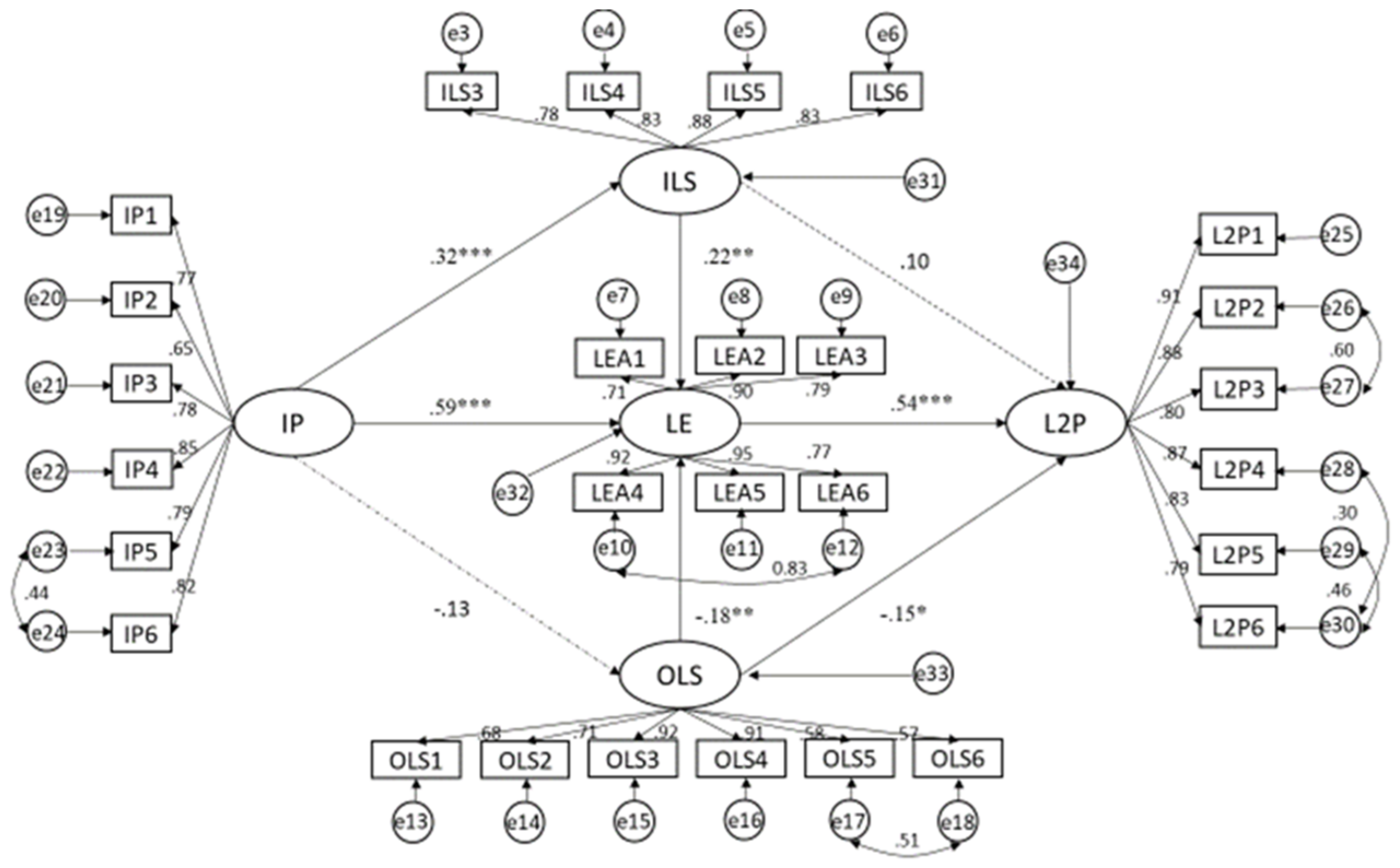

4.2. SEM Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. The Internal Structure of L2MSS

5.2. The Relationships between L2MSS, International Posture and L2 Proficiency

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maffioli, E.M. How Is the World Responding to the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Compared with the 2014 West African Ebola Epidemic? The Importance of China as a Player in the Global Economy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 924–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hagström, L.; Gustafsson, K. The limitations of strategic narratives: The Sino-American struggle over the meaning of COVID-19. Contemp. Secur. Policy 2021, 42, 415–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R. China’s ‘mask diplomacy’ to change the COVID-19 narrative in Europe. Asia Eur. J. 2020, 18, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunford, M.; Qi, B. Global reset: COVID-19, systemic rivalry and the global order. Res. Glob. 2020, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T. Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language: The Japanese EFL Context. Mod. Lang. J. 2002, 86, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780805847291. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z. The L2 motivational self system. In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self; Dörnyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matter: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 9–42. ISBN 9781847691279. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Ushioda, E. Teaching and Researching Motivation, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781315833750. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, T.; Magid, M.; Papi, M. The L2 motivational self system among Japanese, Chinese, and Iranian learners of English: A comparative study. In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self; Dörnyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 66–97. [Google Scholar]

- Csizér, K.; Kormos, J. Learning Experiences, Selves and Motivated Learning Behavior: A Comparative Analysis of Structural Models for Hungarian Secondary and University Learners of ENGLISH; Dörnyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T.; Zenuk-Nishide, L. The impact of learning contexts on proficiency, attitudes, and L2 communication: Creating an imagined international community. System 2008, 36, 566–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chanyoo, N. Motivational Factors and Intended Efforts in Learning East Asian Languages Among Thai Undergraduate Students. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2022, 12, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.B. Willingness to communicate and international posture in the L2 classroom: An exploratory study into the predictive value of willingness to communicate (WTC) and international posture questionnaires, and the situational factors that influence WTC. Polyglossia Asia-Pac. Voice Lang. Lang. Teach. 2013, 25, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsell, B. Gender, international posture, and studying overseas. J. Proc. Gend. Aware. Lang. Educ. 2014, 7, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Botes, E.; Gottschling, J.; Stadler, M.; Greiff, S. A systematic narrative review of International Posture: What is known and what still needs to be uncovered. System 2020, 90, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T. International posture and the ideal L2 self in the Japanese EFL Context. In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self; Dornyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 144–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, J.H.; Han, J.E.; Kim, S.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, H. L2 Motivational Self System, international posture and competitiveness of Korean CTL and LCTL college learners: A structural equation modeling approach. System 2018, 72, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véliz-Campos, M.; Polanco-Soto, M.; Biedroń, A. L2 Motivational Self System, International Posture, and the Socioeconomic Factor in Efl at University Level: The Case of Chile. Psychol. Lang. Commun. 2020, 24, 142–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Differences in the motivation of Chinese learners of English in a foreign and second language context. System 2014, 42, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.-E. L2 Motivational Self System, Attitudes, and Affect as Predictors of L2 WTC: An Imagined Community Perspective. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2014, 24, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Dornyei, Z.; Csizér, K. Motivation, Vision, and Gender: A Survey of Learners of English in China. Lang. Learn. 2015, 66, 94–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T. Taiwanese EFL Learners’ Willingness to Communicate in English in the Classroom: Impacts of Personality, Affect, Motivation, and Communication Confidence. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 2018, 28, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, Y.-K. A structural model for perceptual learning styles, the ideal L2 self, motivated behavior, and English proficiency. System 2014, 46, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.-Y. Structural Relationship Between L2 Learning (De)motivation, Resilience, and L2 Proficiency Among Korean College Students. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2017, 26, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, Y. Structural Relationship Between L2 Learning Motivation and Resilience and Their Impact on Motivated Behavior and L2 Proficiency. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2020, 50, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, R.; Yashima, T. Language proficiency, motivation and affect among Japanese university EFL learners focusing on early language learning experience. ARELE Annu. Rev. Engl. Lang. Educ. Jpn. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. L2 Motivational Self System and Relational Factors Affecting the L2 Motivation of Pakistan Students in the Public Universities of Central Punjab, Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 2013. Available online: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/5054/ (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Moskovsky, C.; Assulaimani, T.; Racheva, S.; Harkins, J. The L2 Motivational Self System and L2 Achievement: A Study of Saudi EFL Learners. Mod. Lang. J. 2016, 100, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Promoting self-determined school engagement: Motivation, learning, and well-being. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Wenzel, K.R., Wigfield, A., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2009; pp. 171–195. ISBN 9780805862904. [Google Scholar]

- Papi, M. The L2 motivational self system, L2 anxiety, and motivated behavior: A structural equation modeling approach. System 2010, 38, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, M.; Abdollahzadeh, E. Teacher Motivational Practice, Student Motivation, and Possible L2 Selves: An Examination in the Iranian EFL Context. Lang. Learn. 2011, 62, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M. A Self System Perspective on Young Adolescents’ Motivation to Learn English in Urban and Rural Settings. Lang. Learn. 2012, 62, 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, A.; Lamb, M. English for Da’wah? L2 motivation in Indonesian pesantren schools. System 2020, 94, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizer, K.; Dornyei, Z. The Internal Structure of Language Learning Motivation and Its Relationship with Language Choice and Learning Effort. Mod. Lang. J. 2005, 89, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizér, K.; Lukács, G. The comparative analysis of motivation, attitudes and selves: The case of English and German in Hungary. System 2010, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, I.K. A multidimensional view of L2 motivation in southeast Spain: Through the ‘ideal selves’ looking glass. Porta Lin-Guarum Rev. Int. Didáctica Las Leng. Extranj. 2019, 31, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, K.; Iwaniec, J. Exploring the relationship between second language learning motivation and proficiency. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2021, 32, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, J.; Kiddle, T.; Csizér, K. Systems of Goals, Attitudes, and Self-related Beliefs in Second-Language-Learning Motivation. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 32, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Su, J. The statistics of English in China. Engl. Today 2012, 28, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Skehan, P. Individual Differences in Second Language Learning. In The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition; Doughty, C.J., Long, M.H., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 589–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.; Kunda, Z. Stability and malleability of the self-concept. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1985; ISBN 9780713164251. [Google Scholar]

- Dornyei, Z.; Ottó, I. Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Mod. Lang. J. 1994, 78, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Mahmoodi, M.H. The L2 motivational self-system: A meta-analysis approach. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornyei, Z.; Ryan, S. The Psychology of the Language Learner Revisited; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978113801873. [Google Scholar]

- Warschauer, M. The Changing Global Economy and the Future of English Teaching. TESOL Q. 2000, 34, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, N. Goal Orientations in Japanese College Students Learning EFLS; Cornwell, S., Robinson, P., Eds.; Aoyama University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2000; ISBN 9784931424050. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, B. Non-Participation, Imagined Communities and the Language Classroom; Breen, M., Ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, M. Integrative motivation in a globalizing world. System 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.S.; Ahn, K.J. English learning motivation and English academic achievement of Korean elementary school students: The effects of L2 selves, international posture, and family encouragement. Mod. Engl. Educ. 2013, 14, 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, R. The L2 self, motivation, international posture, willingness to communicate and can-do among Japanese university learners of English. Lang. Educ. Technol. 2013, 50, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, J.; Csizér, K. Age-Related Differences in the Motivation of Learning English as a Foreign Language: Attitudes, Selves, and Motivated Learning Behavior. Lang. Learn. 2008, 58, 327–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yashima, T.; Zenuk-Nishide, L.; Shimizu, K. The Influence of Attitudes and Affect on Willingness to Communicate and Second Language Communication. Lang. Learn. 2004, 54, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munezane, Y. Attitudes, affect and ideal L2 self as predictors of willingness to communicate. Eurosla Yearb. 2013, 13, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushioda, E. Language learning at university: Exploring the role of motivational thinking. In Motivation and Second Language Acquisition; Dornyei, Z., Schmidt, R., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2001; pp. 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- Noels, K.A. The internalization of language learning into the self and social identity. In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self; Dornyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey, S.; Nowlan, A.G.P. Effect of intercultural contact on L2 motivation: A comparative study. In Language Learning Motivation in Japan; Apple, M.T., Silva, D.D., Fellner, T., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2013; pp. 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T.; Nishida, R.; Mizumoto, A. Influence of learner beliefs and gender on the motivating power of L2 selves. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101, 691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subekti, A.S. L2 Motivational Self System and L2 achievement: A study of Indonesian EAP learners. Indones. J. Appl. Linguistics 2018, 8, 11465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, Y.K. Structural relationships between second-language future self-image and the reading achievement of young Chinese language learners in Hong Kong. System 2018, 72, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.K. Effects of language proficiency on L2 motivational selves: A study of young Chinese language learners. System 2019, 88, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, C.; Im, S. Comparing self-determination theory and the L2 motivational self system and their relationships to L2 proficiency. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2020, 10, 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. L2 Motivation, Demographic Variables, and Chinese Proficiency among Adult Learners of Chinese. J. Lang. Educ. 2020, 6, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hoorie, A.H. The L2 motivational self system: A meta-analysis. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2018, 8, 721–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L. Tibetan CSL learners’ L2 Motivational Self System and L2 achievement. System 2020, 97, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.H. Representaciones transmedia en entornos de lectura analógica. Rev. Tecnol. Cienc. Y Educ. 2019, 14, 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. The impact of online teaching on the English learning motivation of Chinese students during COVID-19. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Education, Culture and Social Sciences, Xi’an, China, 30 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rasiban, L.M. The effect of telegram application in Japanese language distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (ICLLCE 2021), Purwokerto, Indonesia, 19–20 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-O. Facilitating Sustainable Self-Directed Learning Experience with the Use of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Diamantidaki, F. Every cloud has a silver lining: Learning Mandarin during COVID-19. In Trends and Developments for the Future of Language Education in Higher Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y. A study of the washback effects of the College English Test (band 4) on teaching and learning English at tertiary level in China. Int. J. Pedagog. Learn. 2011, 6, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Csizér, K.; Németh, N. Motivation, Language Attitudes, and Globalisation: A Hungarian Perspective; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa, T.; Minoura, Y. Kokoseino kaigai homusutei koka (III): Taido ninshiki niokeruhenka [Effects of high school students’ overseas homestay (III): Changes in attitude and cognition]. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Social Psychology, Tokyo, Japan, 12–13 October 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst, W.B. Bridging Differences; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.Y. Intercultural communication competence: A systems-theoretic view. In Cross-Cultural Interpersonal Communication; Ting-Toomey, S., Korzenny, F., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Kohyama, T.; Fujiwara, T. Tanki kaigaikenshuniokeru nihonjingakuseino sosharu sukirunikansuru chosateki kenkyu. [A study of the social skills of Japanese students in a short-term overseas language seminar]. Mem. Fac. Integr. Arts Sci. III 1991, 15, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T. Influence of personality, L2 proficiency, and attitudes on Japanese adolescents’ intercultural adjustment. JALT J. 1999, 21, 66–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T. Orientations and motivation in foreign language learning: A study of Japanese college students. JACET Bulletin 2000, 31, 121–133. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10112/6873 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Convergence of Structural Equation Modeling and Multilevel Modeling. In The SAGE Handbook of Innovation in Social Research Methods; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 562–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Meng, Z.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, W. Modelling Chinese EFL learners’ flow experiences in digital game-based vocabulary learning: The roles of learner and contextual factors. Comput.Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 34, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustiani, S. Students’ motivation in online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era: A case study. Holistics 2020, 12, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, E.; Li, J. What is the value essence of “double reduction” (Shuang Jian) policy in China? A policy narrative perspective. Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subakthiasih, P.; Putri, I.G.A.V.W. An Analysis of Students’ Motivation in Studying English During Covid-19 Pandemic. Linguist. Engl. Educ. Art (LEEA) J. 2020, 4, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-M. The effects of study-abroad experiences on EFL learners’ willingness to communicate, speaking abilities, and participation in classroom interaction. System 2014, 42, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Lee, J. The effects of ideal and ought-to L2 selves on Korean EFL learners’ writing strategy use and writing quality. Read. Writ. 2018, 32, 1129–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, M.; Teimouri, Y. Language Learner Motivational Types: A Cluster Analysis Study. Lang. Learn. 2014, 64, 493–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C.C.; Aron, A. Aspects of possible self that predict motivation to achieve or avoid it. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 39, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Bybee, D.; Terry, K. Possible selves and academic outcomes: How and when possible selves impel action. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toyama, M.; Yamazaki, Y. Anxiety reduction sessions in foreign language classrooms. Lang. Learn. J. 2019, 49, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, D.B. Twenty approaches to individual change. Pers. Guid. J. 1977, 55, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, W.J. Rational-Emotive Education: A Manual for Elementary School Teachers; Institute for Rational Living: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

| Reliability | Convergent Validity | Discriminant Validity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | Latent Variable Correlations | |||||

| ILS | OLS | LE | IP | L2P | ||||

| ILS | 0.90 | 0.908 | 0.712 | 0.844 | ||||

| OLS | 0.88 | 0.905 | 0.615 | −0.002 | 0.784 | |||

| LE | 0.93 | 0.897 | 0.594 | 0.373 ** | −0.122 | 0.771 | ||

| IP | 0.90 | 0.893 | 0.582 | 0.307 ** | −0.075 | 0.591 ** | 0.763 | |

| L2P | 0.94 | 0.921 | 0.661 | 0.334 ** | −0.234 ** | 0.562 ** | 0.501 ** | 0.813 |

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILS | 1 | 6 | 4.97 | 0.940 | −0.856 | 1.065 |

| OLS | 1 | 6 | 3.11 | 1.101 | 0.126 | −0.004 |

| LE | 1 | 6 | 3.84 | 1.114 | −0.162 | −0.228 |

| IP | 1 | 6 | 4.40 | 0.884 | −0.213 | 0.892 |

| L2P | 1 | 5.33 | 3.63 | 0.995 | −0.836 | 0.464 |

| χ2/df | CFI | GFI | IFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | 1.628 | 0.935 | 0.880 | 0.936 | 0.927 | 0.065 |

| Threshold | <3 | >0.900 | >0.900 | >0.900 | >0.900 | <0.100 |

| Evaluation | Good | Good | Close | Good | Good | Good |

| Path | Estimate | SE | CR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP → ILS | 0.323 | 0.106 | 3.518 | *** |

| IP → LE | 0.589 | 0.089 | 6.484 | *** |

| IP → OLS | −0.129 | 0.072 | −1.399 | 0.162 |

| ILS → LE | 0.220 | 0.060 | 3.095 | 0.002 ** |

| OLS → LE | −0.177 | 0.087 | −2.522 | 0.012 * |

| ILS → L2P | 0.096 | 0.085 | 1.234 | 0.217 |

| LE → L2P | 0.539 | 0.119 | 5.823 | *** |

| OLS → L2P | −0.145 | 0.120 | −1.929 | 0.045 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, J. L2 Motivational Self System, International Posture and the Sustainable Development of L2 Proficiency in the COVID-19 Era: A Case of English Majors in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138087

Zhao X, Xiao W, Zhang J. L2 Motivational Self System, International Posture and the Sustainable Development of L2 Proficiency in the COVID-19 Era: A Case of English Majors in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):8087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138087

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xi, Wei Xiao, and Jiajia Zhang. 2022. "L2 Motivational Self System, International Posture and the Sustainable Development of L2 Proficiency in the COVID-19 Era: A Case of English Majors in China" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 8087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138087

APA StyleZhao, X., Xiao, W., & Zhang, J. (2022). L2 Motivational Self System, International Posture and the Sustainable Development of L2 Proficiency in the COVID-19 Era: A Case of English Majors in China. Sustainability, 14(13), 8087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138087