Second Language Teaching with a Focus on Different Learner Cultures for Sustainable Learner Development: The Case of Sino-Korean Vocabulary

Abstract

:1. Introduction

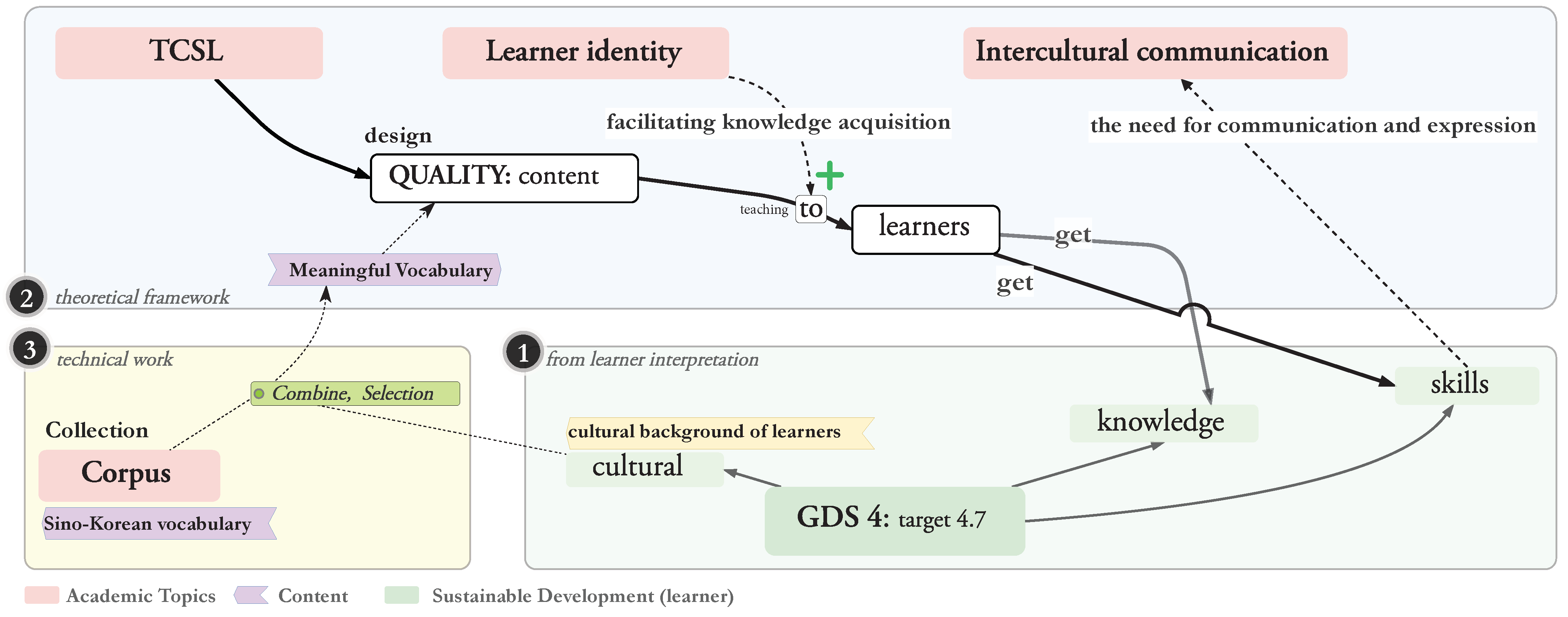

- Label-1 is an interpretation of SDG 4.7 from the learner’s perspective, in which we argue that culture, knowledge, and skills are essential for learners to achieve individual sustainability.

- Label-2 we reviewed the literature related to TCSL, learner identity, and intercultural communication (in Section 2) and suggested that TCSL should focus on the cultural background of learners.

- Label-3 is a specific research work that involves collecting a large number of words through technological means, referring to authoritative dictionaries (see Table A2) for transcription, deletion, and retaining culturally relevant pedagogical vocabulary for learners as a supplement to the materials.

- What Sino-Korean vocabulary can we provide for TCSL that are culturally distinctive to Korea?

- Do the extracted distinctive cultural words have any usable value in terms of teaching materials?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Influence of Different Learner Cultures on Learner Identity on the Construction of Knowledge

2.2. The Importance of Different Learner Cultures in Intercultural Communication Skills

2.3. Sino-Korean Vocabulary Studies

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Definition

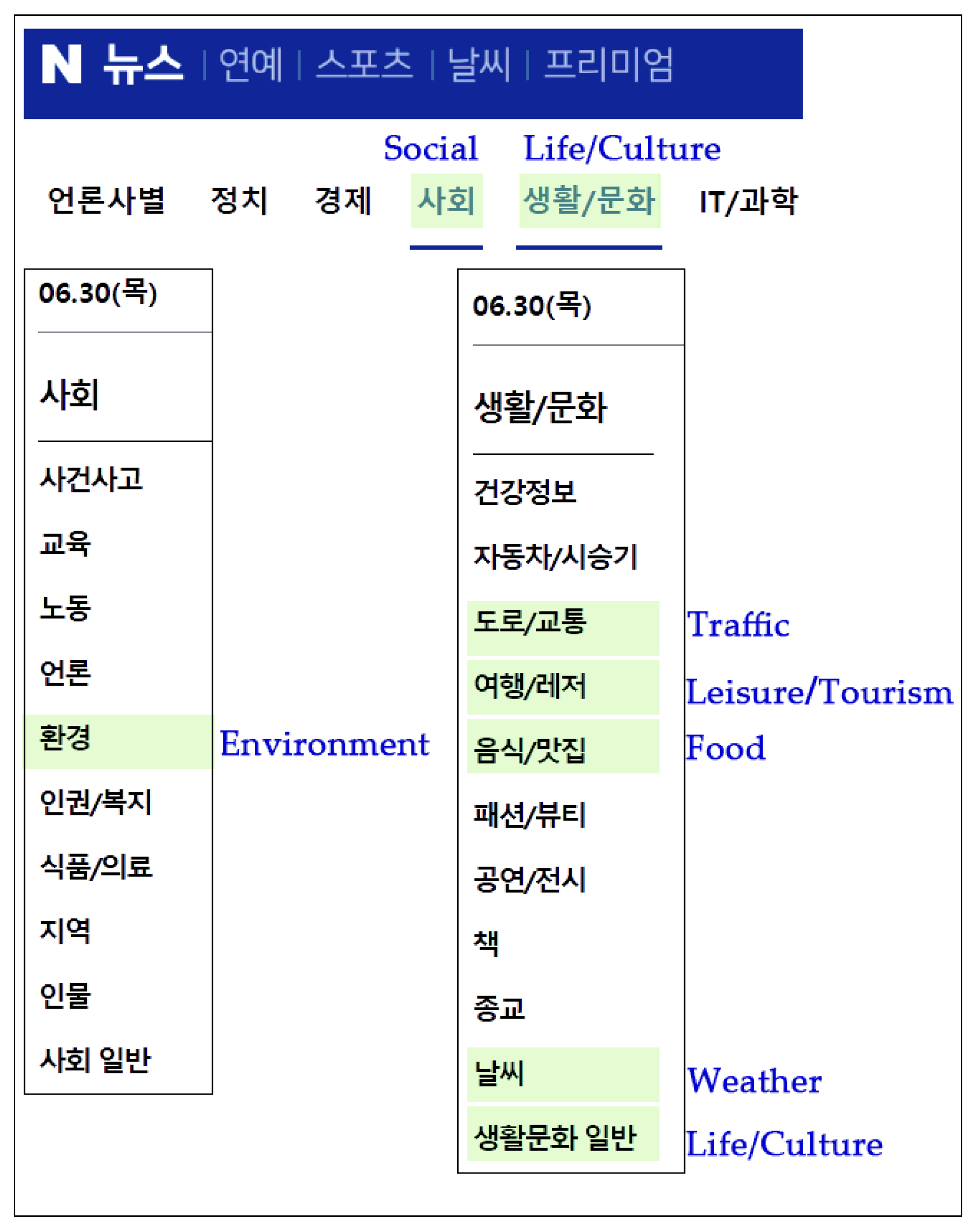

3.2. Corpus Collection

3.3. Corpus Processing

| Algorithm 1: Text Mining: Keyword Extraction Algorithm. |

|

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Vocabulary Extraction

4.2. An Examination of Sino-Korean Vocabulary in ECLCK

- Vocabulary syllabus: the Chinese Proficiency Vocabulary and Chinese Character Grades Syllabus (CPV-CCGS) (1992) [48].

- The Graded Chinese Syllables, Characters and Words for the Application of Teaching Chinese to the Speakers of other Languages (GCS) (2010) [49].

- The new Chinese Proficiency Test vocabulary (HSKv) (2012) [50].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPV-CCGS | Chinese Proficiency Vocabulary and Chinese Character Grades Syllabus (1992) |

| ESL | English as a Second Language |

| ECLCK | The Korean Version of Experience Chinese: Living in China |

| GCS | The Graded Chinese Syllables, Characters and Words for the Application |

| of Teaching Chinese to the Speakers of other Languages (2010) | |

| IDF | Inverse Document Frequency |

| HSK | Chinese Language Proficiency Test |

| HSKv | New Chinese Proficiency Test Vocabulary (2012) |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SLT | Second Language Teaching |

| TCSL | Teaching Chinese as a Second Language |

| TF | Term Fequency |

Appendix A

| Index | Folders/File Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| File | [00]RawData_year_title_topic_content | the original text data we obtained from NEVER website; |

| File | [01]topic_all_term_info_withDoc_top10 | the result data calculated from steps 1 to 12 of the Algorithm 1, (i.e., the data set of the top 10 keywords for each document in each topic ); |

| File | [02]keyWordTop10_head6000_withChinese | the dataset of Chinese translation using the dictionary mentioned in Table A2 after step 13 of the algorithm, where the first 6000 words were intercepted; |

| File | [03]ChineseKoreanWords_Selection_Supplement | the dataset of manually selected words used to supplement country-specific textbooks; |

| File | longTable_ChineseKoreanWords_Selection_Supplement.pdf | the dataset of manually selected words used to supplement country-specific textbooks long table pdf verison. |

| No. | Dictionary Resources |

|---|---|

| 1 | 에듀월드 표준한한중사전–Standard Korean-Chinese Dictionary https://stdict.korean.go.kr/main/main (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 2 | 한국관광공사 관광용어 외국어 용례사전–Korea Tourism Organization Dictionary of Foreign Language Terms for Tourism http://www.visitkorea.or.kr/intro.html (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 3 | 고려대 한한중사전–Koryo University Chinese-Korean Translation Dictionary https://riks.korea.ac.kr (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 4 | 삼정 KPMG 회계세무용어사전–Mitsui KPMG Dictionary of Accounting and Taxation Terms https://book.naver.com/bookdb/book_detail.nhn?bid=2090133 (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 5 | 한중상품용어사전–Chinese-Korean Dictionary of Product Terms https://book.naver.com/bookdb/book_detail.nhn?bid=7011762 (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 6 | 라인딕 중영사전–Leyendyk’s Chinese-English Dictionary https://dict.naver.com/linedict/zhendict/#/cnen/home (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 7 | 고려대 중한사전–Koryo University Chinese-Korean Dictionary https://book.naver.com/bookdb/book_detail.nhn?bid=26385 (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 8 | 한국외대 한국어학습사전–Korean Language Learning Dictionary https://krdict.korean.go.kr/mainAction (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 9 | 오픈마인드 e-한자–Chinese Characters http://e-hanja.lib.studynow.kr (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 10 | 호텔스컴바인 호텔정보–hotels combined https://hotels.biyi.cn (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 11 | 에듀월드 표준중중한사전–Chinese-Korean Dictionary in World Standard https://book.naver.com/bookdb/book_detail.nhn?bid=9374403 (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 12 | 교학사 현대중한사전–Teaching History https://book.naver.com/bookdb/book_detail.nhn?bid=2533229 (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 13 | 학고방 최신중한신조어사전–Latest Chinese and Korean Newly Made Words Dictionary https://book.naver.com/bookdb/book_detail.nhn?bid=6060672 (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 14 | 건홍리서치 중국금융경제사전–Chinese Financial and Economic Dictionary https://book.naver.com/bookdb/book_detail.naver?bid=6050527 (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

| 15 | 연세대 한국어학당 국가별 대표음식–Yonsei University Korean Language School Countries’ Representative Diet https://www.yskli.com (accessed on 5 March 2022) |

References

- Lawson, A. Learner identities in the context of undergraduates: A case study. Educ. Res. 2014, 56, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schumann, J.H. Research on the acculturation model for second language acquisition. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 1986, 7, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al harthi, S. Second Language Learning and the Clash of Civilizations. Arab. World Engl. J. 2017, 8, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alujević, M.; Braović Plavša, M. The effect of psychotypology and linguistic attitudes towards target language on the occurrence of transfer on the receptive level upon the first contact of croatian speakers with italian as L2. Folia Linguist. Litt. 2021, XII, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, D.; Corrius, M. The role of the learner’s native culture in EFL dictionaries: An experimental study: Lexicosurvey. Lexikos 2013, 23, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, F. Exploring the Reconstruction of Chinese Learners’ National Identities in Their English-Language-Learning Journeys in Britain. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2011, 10, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starinina, O.V. Self-identification Features of Russian-speaking Primary Schoolchildren in the Cultural Aspect of Educational Activity as a Way to Optimize Learning a Foreign Language. In Proceedings of the VI International Forum on Teacher Education, Kazan, Russian, 27 May–9 June 2020; Gafurov, I., Valeeva, R., Eds.; Pensoft Publishers: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2020; pp. 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.M. Identities constructed in difference: English language learners in China. J. Pragmat. 2010, 42, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckhohn, C.E.; Murray, H.A.; Schneider, D.M. Personality In Nature, Society, Furthermore, Culture; Personality in Nature, Society, and Culture; Knopf: Oxford, UK, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Pang, S. Research on Cross-cultural Communication and Language Awareness. Foreign Lang. Res. Northeast. Asia 2013, 1, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, H.M. The Korean Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, H.M. Korean Language In Culture Furthermore, Society; KLEAR textbooks in Korean Language; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, M.; Grady, W.O. Handbook of Korean Vocabulary: A Resource for Word Recognition and Comprehension; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- An, F.; Zheng, X. Overview of Korean Traditional Culture; Yanbian University Press: Yanji, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, G. Introduction to Korean Culture, 1st ed.; Shandong University Press: Jinan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Qìzhong, S. The structure of Chinese characters in Modern Mandarin. Korean Lang. 1992, 1, 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. A comparative study of Chinese vocabulary and Korean Chinese words. J. Liaoning Univ. 1999, 4, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Weedon, C. Feminist Practice & Poststructuralist Theory; Blackwell Pub: Derbyshire, UK, 1996; ISBN 9780631198253. [Google Scholar]

- Takkaç Tulgar, A. Exploring the bi-directional effects of language learning experience and learners’ identity (re)construction in glocal higher education context. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashen, S. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition; Language Teaching Methodology Series; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, P. Education of Korean Values and Culture through Film-With a focus on intercultural competence. J. Int. Netw. Korean Lang. Cult. 2018, 15, 189–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C. ‘The inappropriateness of language’: Discourses of power and control over languages beyond English in primary schools. Lang. Educ. 2019, 33, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathje, S. Intercultural Competence: The Status and Future of a Controversial Concept. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2007, 7, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, F. The World Is Flat; Farrar. Straus and Giroux: Huddersfield, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Lobatón, J.C. Language learners’ identities in EFL settings: Resistance and power through discourse. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. 2012, 14, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvesko, T.V.; Basueva, N.Y. Conceptual-categorical approach to developing intercultural professional discourse competence. Yazyk i Kul’tura 2018, 42, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. Standards for Foreign Language Learning in the 21st Century; National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project: Yonkers, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe; Council for Cultural Co-operation; Education Committee; Modern Languages Division (Eds.) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scrimgeour, A.; Wilson, P. International Curriculum for Chinese Language Education. Babel 2009, 43, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D. A Tentative Analysis of Learning Characteristics of Culture-bound Words Among Korean Students. Chin. Lang. Learn. 2000, 6, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H. The Study on the Transfer of Chinese-originated Words in Korean Language. Chin. Lang. Learn. 2000, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Z. The impact of Korean-Chinese twin words on Chinese language learning. In Proceedings of the The 8th International Conference on Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language, Kunming, China, 25–27 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, R. Towards a New Approach to Constructing a Country-Specific Word List for Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language: The Case of Korean. Appl. Linguist. 2005, 2, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Römer, U. Corpus Research Applications in Second Language Teaching. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 31, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavlova, O.Y. Linguistic corpora in foreign language teaching. Yazyk i Kul’tura 2021, 54, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T. Non-nativelike outcome of naturalistic child L2 acquisition of Japanese: The case of noun–verb collocations. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2022, 60, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gong, X. The General, Regional, First-language-Type and Country-Type of Textbooks of Chinese as a Foreign Language: An Example of the Pluralistic Approach. Chin. Lang. Learn. 2015, 1, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. Dui Wai Han Yu Jiao Cai Chu Ban De Wen Hua Cha Yi Chong Tu Yu Rong Tong Ce Lue [ Cultural Differences and Integration Strategies in the Publication of Chinese Teaching Materials for Foreigners ]. View Publ. 2016, 4, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. A Study on Learning Activities in Korean Textbooks on the Sociocultural Perspective of Communication. J. Int. Netw. Korean Lang. Cult. 2017, 14, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, S. The contribution of learner corpora to reference and instructional materials design. In The Cambridge Handbook of Learner Corpus Research; Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, H.L. Do MFL Learners in Malaysia Need ‘Mandarin for Travelling’? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 134, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, X.; Yue, J. The Korean Version of Experience Chinese: Living in China (Ti Yan Han Yu Sheng Huo Pian) (ECLCK); Higher Education Press (Gao deng jiao yu chu ban she): Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Salton, G.; Yu, C.T. On the Construction of Effective Vocabularies for Information Retrieval. Sigir Forum 1973, 9, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.S. Index term weighting. Inf. Storage Retr. 1973, 9, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, A.; Ullman, J.D. Data Mining. In Mining of Massive Datasets; Rajaraman, A., Ullman, J.D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salton, G.; Buckley, C. Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shang, Y.; Wang, H. Centennial Korea (Bai Nian Han Guo); Jilin Publishing Group: Jilin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Proficiency Test. The Chinese Proficiency Vocabulary and Chinese Character Grades Syllabus (Han YU Shui Ping Ci Hui YU Han Zi Deng Ji Da Gang), xiu ding ben, di 1 ban ed.; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.Y.; Fei, M.J. The Graded Chinese Syllables, Characters and Words for the Application of Teaching Chinese to the Speakers of Other Languages (Han YU Guo Ji Jiao YU Yong Yin Jie Han Zi CI Hui Deng Ji Hua Fen); Beijing Language and Culture University Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hanban. New HSK Vocabulary. 2012. Available online: http://www.chinesetest.cn/godownload.do (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Zheng, D. Enhancing Basic Research for Teaching Chinese as Foreign Language. Chin. Lang. Learn. 2004, 5, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

| Topic | File | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 도로/교통: Traffic | 20240 | 2792796 | Transportation_rawData.xlsx |

| 여행/레저: Leisure and Tourism | 206464 | 41407569 | Leisure travel_rawData.xlsx |

| 음식: Food | 37006 | 5796015 | Foo and drink_rawData.xlsx |

| 날씨: Weather | 190025 | 17529289 | Weather_rawData.xlsx |

| 생활문화 일반: Life and Culture | 266316 | 42448397 | Living Culture_rawData.xlsx |

| 환경: Environment | 161733 | 16720160 | Environment_rawData.xlsx |

| 도로/교통 | 여행/레저 | 음식 | 날씨 | 생활문화 일반 | 환경 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic | Leisure/Tourism | Food | Weather | Life/Culture | Environment | |||||||

| Index | SK | C | SK | C | SK | C | SK | C | SK | C | SK | C |

| 1 | 지하철 | 地下铁 | 울산 | 蔚山 | 한우 | 韩牛 | 기온 | 气温 | 북한 | 北韩 | 낙동강 | 洛东江 |

| 2 | 고속도로 | 高速道路 | 인천 | 仁川 | 한식 | 韩食 | 태풍 | 台风 | 화장품 | 化妆品 | 폐기물 | 废弃物 |

| 3 | 교통 | 交通 | 한국인 | 韩国人 | 요리 | 料理 | 황사 | 黄沙 | 의원 | 议员 | 지진 | 地震 |

| 4 | 전동차 | 电动车 | 화천군 | 华川郡 | 홍삼 | 红参 | 지진 | 地震 | 회장 | 会长 | 기후 | 气候 |

| 5 | 열차 | 列车 | 섬진강 | 蟾津江 | 차 | 茶 | 매우 | 梅雨 | 조선 | 朝鲜 | 환경부 | 环境部 |

| 6 | 국제선 | 国际线 | 강원도 | 江原道 | 라면 | 拉面 | 절기 | 节气 | 대통령 | 大统领 | 가습기 | 加湿器 |

| 7 | 철도 | 铁道 | 대전 | 大田 | 식당 | 食堂 | 폭설 | 暴雪 | 한류 | 韩流 | 수질 | 水质 |

| 8 | 국도 | 国道 | 통영 | 统营 | 삼계탕 | 参鸡汤 | 폭우 | 暴雨 | 저작권 | 著作权 | 지구 | 地球 |

| 9 | 인천공항 | 仁川空港 | 한우 | 韩屋 | 연어 | 鲢鱼 | 강풍 | 强风 | 광화문 | 光化门 | 산간 | 山间 |

| 10 | 국내선 | 国内线 | 춘천 | 春川 | 전통주 | 传统酒 | 온화 | 温和 | 전통 | 传统 | 대기 | 大气 |

| 11 | 휴게소 | 休憩所 | 금강산 | 金刚山 | 냉면 | 冷面 | 건조 | 干燥 | 사장 | 社长 | 오염 | 污染 |

| 12 | 주차장 | 驻车场 | 목포 | 木浦 | 소주 | 烧酒 | 대설 | 大雪 | 만화 | 漫画 | 생태계 | 生态系 |

| 13 | 항공사 | 航空社 | 성당 | 圣堂 | 교맥 | 荞麦 | 청명 | 清明 | 백제 | 百济 | 해양 | 海洋 |

| 14 | 호남선 | 湖南线 | 경기도 | 京畿道 | 음료 | 饮料 | 고온 | 高温 | 평양 | 平壤 | 야생동물 | 野生动物 |

| 15 | 연비 | 燃费 | 안면도 | 安眠岛 | 죽 | 粥 | 피서 | 避暑 | 고려 | 高丽 | 습지 | 湿地 |

| 16 | 고가 | 高架 | 진도 | 珍岛 | 두부 | 豆腐 | 기상청 | 气象厅 | 한복 | 韩服 | 방역 | 防疫 |

| 17 | 경부선 | 京釜线 | 단양 | 丹阳 | 곰탕 | 骨汤 | 온열 | 温热 | 청와대 | 靑瓦台 | 공기 | 空气 |

| 18 | 기차표 | 汽车票 | 장흥 | 长兴 | 인삼 | 人参 | 창원 | 常温 | 박물관 | 博物馆 | 폐수 | 废水 |

| 19 | 고장 | 故障 | 울진 | 蔚珍 | 생강 | 生姜 | 한기 | 寒气 | 아리랑 | 阿里郎 | 중금속 | 重金属 |

| 20 | 인천지하철 | 仁川地铁 | 속초 | 束草 | 유자 | 柚子 | 뇌우 | 雷雨 | 숭례문 | 崇礼门 | 발전소 | 发电所 |

| CPV-CCGS [48] Level | ♣ | ♠ | % | GCS [49] Level | ♣ | ♠ | % | NHKv [50] Level | ♣ | ♠ | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | 1033 | 91 | I.① | 509 | 61 | HSK1 | 150 | 41 | |||

| (B) | 2018 | 11 | I.② | 835 | 20 | HSK2 | 150 | 23 | |||

| (C) | 2202 | 2 | I.③ | 901 | 3 | HSK3 | 300 | 13 | |||

| (D) | 3569 | 1 | II | 3211 | 20 | HSK4 | 600 | 9 | |||

| out | 6 | III | 4175 | 5 | HSK5 | 1300 | 6 | ||||

| other | 7 | adv. | 1461 | 0 | HSK6 | 2500 | 1 | ||||

| out | 4 | out | 4 | ||||||||

| other | 5 | other | 21 | ||||||||

| total |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Wei, H.; Li, Y. Second Language Teaching with a Focus on Different Learner Cultures for Sustainable Learner Development: The Case of Sino-Korean Vocabulary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137997

Li Y, Wei H, Li Y. Second Language Teaching with a Focus on Different Learner Cultures for Sustainable Learner Development: The Case of Sino-Korean Vocabulary. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137997

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yishu, Huiping Wei, and Yongjian Li. 2022. "Second Language Teaching with a Focus on Different Learner Cultures for Sustainable Learner Development: The Case of Sino-Korean Vocabulary" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137997

APA StyleLi, Y., Wei, H., & Li, Y. (2022). Second Language Teaching with a Focus on Different Learner Cultures for Sustainable Learner Development: The Case of Sino-Korean Vocabulary. Sustainability, 14(13), 7997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137997