Abstract

Prior studies have examined the historical evolution, multiple stakes, measurements and operation models of graduate employability, and the researches on graduate employability have gradually shifted to the perspective of employers with wider labor market uncertainty and higher education massification. However, there is still a gap in research on the demand for graduate employability by employers in national high-end equipment manufacturing that work closely with higher education in scientific research. Namely, it remains unclear what really matters in the processes of employers’ recruitment decisions in national high-end equipment manufacturing. Drawing on Yorke’s definition and CareerEDGE model, this study defines graduate employability as a set of achievements—skills, understandings and personal attributes—that makes graduates more likely to gain employment in national high-end equipment manufacturing, including “emotional intelligence”, “knowledge and skills”, “generic skills”, “work experience”, “character and personality”. Owing to the importance and arduousness of national high-end equipment manufacturing historical mission and main tasks, we argue that employers pay more attention to graduate employability in the recruitment process. Empirically examining based on 831 questionnaires from employers of national high-end equipment manufacturing in China, we show that employers prefer graduates with higher levels of “cooperative innovation ability”, “knowledge and skills”, “stress management and adaptation” within Chinese national characteristic discipline programs. Particularly, although employers in national high-end equipment manufacturing have always emphasized employees’ loyalty and dedication, “character and personality” of a graduate does not have a direct effect on employer hiring preference, but instead the effect of cooperative innovation ability and knowledge and skills are fully moderated by character and personality.

1. Introduction

Collaborations between universities and the national high-end equipment manufacturing have a long history, and these partnerships are viewed as being critical to driving national economic development and strengthening national innovation capabilities, particularly in areas related to national and homeland security. For example, American research universities devoted themselves to national scientific research at the request of the federal government during World War I and made outstanding contributions in ordnance, chemical weapons, submarine detection, etc., and even in the project of chemical weapons research and development, with more than 1900 scientists involved [1]. During World War II, at least 15 of the 32 research universities included in the Association of American Universities (AAU) participated in the federal government’s research activities [2].

Partnerships between universities and the national high-end equipment manufacturing can take many different forms. Some examples of collaborations between U.S. Department of Defense Laboratories and universities include Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs), Collaborative Research Alliances (CRAs), Collaborative Technical Alliances (CTAs), and University Affiliated Research Centers (UARCs) [3]. These different forms are categorized thematically as Research Partnership Agreements, Resource Use Agreement, Personnel Exchange Agreements, Educational Agreements, and other types of agreements [3]. Such agreements allow the national high-end equipment manufacturing to leverage external expertise, additional infrastructure and capabilities necessary that are available for universities to fulfill their research missions, which is due to the national high-end equipment manufacturing that is generally engaged in mission-oriented research that requires expertise in multiple scientific and technical disciplines. Likewise, universities can send researchers, students, and postdoctoral researchers to work on critical national high-end equipment manufacturing related projects, and simultaneously grow the talent pipeline in critical areas of science and technology. Moreover, research partnerships can also provide exciting employment opportunities for university students involved in these collaborative projects. For example, since 2012, the “National Centers of Academic Excellence” was jointly established by the US Department of Defense; the National Security Agency and the Department of Homeland Security has implemented a cyber defense talent funding program in 145 colleges and universities in the United States; and 85% of graduates are employed in various departments of the defense and military [4].

Such mutually beneficial partnerships provide a successful reference for subsequent research universities to participate extensively in national high-end equipment manufacturing related research. For example, in the period 2001–2006, 26 UK universities were involved in 1900 military research projects with an estimated total value of £725 million [5]. It is estimated that by the end of 2006, the U.S. Department of Defense had military-related research contracts with 946 domestic universities and colleges, and 161 universities in 33 other countries around the world, including Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom [6,7]. In FY2022, Japan plans to accelerate the implementation of “Innovative Science and Technology Initiative for Security” program regarding basic research at universities with total budget of ¥11.2 billion [8]. Higher education institutions are becoming increasingly more prominent in military-related research from government and the armament industry.

Although compared with countries such as Europe and the United States, research universities in China started relatively late in participating in national high-end equipment manufacturing research. Since the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established more than 70 years ago, more and more colleges and universities have become involved in the scientific research of national high-end equipment manufacturing, with the increasing attention on national science and technology innovation by the Chinese government. For example, since the 1980s, China has successively launched major projects such as National High-Tech Research and Development Program (863 Program), National Key Basic Research Program (973 Program). As of 2019, 37 of the 60 national science and technology key laboratories have been built in colleges and universities of China [9].

As a significant component of national science and the technology talent-cultivation system, Chinese national characteristics discipline programs referred in this study were initiated at the beginning of the 10th Five-Year Plan period (2001–2005) to consolidate the strength of colleges and universities that prepare graduates to work in national high-end equipment manufacturing by offering specialized training in national characteristics disciplines, improving their ability to equip personnel, strengthening basic research and frontier technology research, and increasing technical reserves, thereby providing important support for the promotion of innovation and development in national high-end equipment manufacturing and the science and technology industry. Owing to the specialized nature of national high-end equipment manufacturing, the national generic disciplines and specialties cannot fully satisfy the industry’s need for qualified personnel, and as national high-end equipment manufacturing has not paid enough attention to the training of personnel in basic research, meeting the sustained demand for personnel with the special training required by national high-end equipment manufacturing is difficult. It is reported that a total of 280 national characteristics discipline programs referred in this study have been deployed in 53 colleges and universities during the 13th Five-Year Plan period [10].

Up to now, this national characteristics discipline program in China’s national science and technology talent-cultivation system led has been expanded to 7 universities directly under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) as the core, more than 40 colleges and universities co-built with the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the local government respectively as the supplement [11]. According to incomplete statistics, these universities have sent a total of nearly 125,000 graduates to national high-end equipment manufacturing during the 12th Five-Year Plan period [12]. College and university graduates of national characteristics discipline programs have become a new force in the building up of the national science and technology innovation system. However, the current training model for personnel qualified in national characteristics disciplines cannot adequately satisfy the need for the development of national high-end equipment manufacturing personnel in the new era and is not in line with the collaborative innovation and development trend of the national high-end equipment manufacturing or the requirements for the in-depth development of industrial integration, which is mainly reflected in the structural imbalance in the supply and demand of personnel. For instance, the proportion of graduates from 7 universities directly under the MIIT of China entering the national high-end equipment manufacturing did not exceed 45% from 2014 to 2016 [13]. This gives rise to problems such as graduates’ innovative ability and comprehensive quality not being properly qualified for the national high-end equipment manufacturing science and technology positions [14].

To respond to this challenge, taking account of employers’ views for identifying what expected skills national high-end equipment manufacturing demanded, as well as what national characteristics disciplines programs of higher education should be providing, are crucial. However, no research has previously been conducted on the employability of graduates of national characteristics disciplines programs. This study aims to explore the indicator system of graduates’ employability which are preferred by the employers of national high-end equipment manufacturing in China, and its impact on employers’ hiring preference in the recruitment process

The remaining parts of this paper are arranged as follows. The next section establishes the indicator system of graduates’ employability based on the historical evolution and multiple stakes of employability, multidimensional operationalization and measurement of graduate employability, putting forward the research hypotheses and the theoretical model. The third section describes the process of scale development, data collection and variables measurement. In the Section 4, a latent moderating structure model is established in this study to explore the moderating effect of the character and personality of graduates on the above relationship to allow us to examine whether there are mediating or moderating variables that affect employers’ hiring preferences. Finally, the paper discusses the research results, draws conclusions, and points out future research directions. We seek to fill a gap in the current research and provides a theoretical basis and practical support for the reform of the personnel training mode of national characteristics disciplines programs at colleges and universities (supply-side structural reform).

2. Theory Development and Hypotheses

2.1. Historical Evolution of Employability

The concept of employability was first proposed by the British scholar Beveridge in 1909. The research debate on the concept of employability can be traced back at least a century, and many views emerged, which can be summarized into seven versions—namely, Dichotomic employability, Socio-medical employability, Manpower policy employability, Flow employability, Labor market performance employability, Initiative employability, Interactive employability [15,16,17]. These seven versions of the concept of employability can be identified as emerging in three waves [16]. The first wave, and the first use of the concept, centering on “dichotomic employability”, emerged in the early decades of the 20th century. This simplistic version of the concept employability is useful for distinguishing the “employable” from the “unemployable” (i.e., those eligible for welfare benefits). The second wave began around the 1960s, as a labor market policy tool, and the concept of employability was then developed so as to achieve full employment through government measures designed to facilitate access to the labor market, especially for the most needy in a social democrat conception of society. Three very different versions of the concept were used by statisticians, social workers and labor market policymakers. ”Socio-medical employability”, ”manpower policy employability” and ”flow employability” focused on identifying and measuring the distance between individual characteristics and the demands of work in the labor market. The third wave, originated in the 1980s and developed in the 1990s, considered employability as a way to increase individual flexibility and addressed the role of individuals in keeping and developing their employability during a transition between two occupations and within a specific occupation. Three new formulations of employability were put forward, including the outcome-based ”labor market performance employability”, “initiative employability”, with its focus on individual responsibility, and ”interactive employability”, which “maintains the focus on individual adaptation but introduces a collective/interactive priority” [15].

2.2. Multiple Perspectives of Employability

- (1)

- Governmental and educational perspectives of employability

A first set of scientific studies has focused on the government policies and education policies for developing employability in different countries [18,19]. They have studied employability improvement strategies implemented by the government for different populations—such as workers, the unemployed, young people in difficulties, ethnic minorities, and the disabled—and argued that government and educational policies should give priority to providing the assistance of professional skills to disadvantaged individuals [18]. Employability was reflected in the UK National Employment Action Plan and the Government’s Work Welfare Agenda [20,21,22] and has become an economic strategic objective of labor market policy in the world [23,24].

- (2)

- Organizational perspectives of employability

A second set of scientific studies that examines employability is from a perspective of organization or employer. According to the resource-based view of the firm [25,26], competences are one category of possible resources that enable firms to achieve performance and (sustained) competitiveness. In such a context, enterprises must improve their competitiveness, adaptability and flexibility by improving the employability of their employees to cope with challenges in the external environment, such as technological development, globalization, new customer requirements, new laws and regulations, etc. [27,28]. Van Dam proposed the concept of ‘employability orientation’ to describe employees’ attitudes towards employability activities, which consist of the development of work knowledge and experience, career management, job training, keeping oneself up-to-date concerning internal job vacancies, an active search for opportunities to improve one’s work situation and so on [29].

- (3)

- Individual perspectives of employability

A third group of studies concentrates on individuals’ employability skills and attributes, which can be seen as broadly covering the overlapping: essential attributes (basic social skills, reliability, etc.); personal competencies (diligence, motivation, confidence, etc.); basic transferable skills (including literacy and numeracy); key transferable skills (problem-solving, communication, adaptability, work-process management, team-working skills); high-level transferable skills (including self-management, commercial awareness, possession of highly transferable skills); qualifications and educational attainment; work knowledge base (including work experience and occupational skills); and labor market attachment (current unemployment/employment duration, work history, etc.) [30]. These employability skills and attributes are some parallels between the categorisation of skills and attributes suggested here and human capital theory [31], transferable skills [32] and wider discussions of skills acquisition and intelligence [33]. Bernston and Marklund [34] define employability as “an individual’s perception of their likelihood of obtaining a new job”, including “perceived skills, experience, networks, personal characteristics, and labor market knowledge”. Rothwell et al. [35] take a perception-centred perspective and define employability as “the perceived ability to obtain sustainable employment appropriate to the level of one’s qualifications”. McQuaid and Lindsay present a broad framework for analysing employability built around individual factors, personal circumstances and external factors, which acknowledges the importance of both supply and demand-side factors [30]. There are also some researchers who regard employability as a trait, arguing that employability is a multidimensional combination of personal characteristics that help employees adapt to work and occupational environments, as well as career success [36,37].

2.3. Graduate Employability

Since the 1960s, numerous studies have been published explaining the relationship between higher education (HE) and employment, mainly applying human capital theory [38,39] or signaling theory [40,41,42]. However, the greater diversification of university graduates resulting from the massification of HE [43] and the widening uncertainty of labor market demand in a post-industrial knowledge-driven economy [44] have created considerable changes in the relationship between HE and the labor market. The changes have raised concerns among policymakers, the corporate world, higher education institutions about a mismatch between the skills graduates possess and those demanded by employers. As a result, the issue of graduate employability, an ongoing policy priority for HE policymakers in many advanced Western economies, is again in the spotlight.

Graduate employability here is not “graduate employment rate” which lacks validity [45], but rather the importance of “employment skills” in order to prepare graduates to meet the demands of an increasingly flexible labor market. For example, Hillage and Pollard [18] suggest that employability is about being capable of obtaining and keeping fulfilling work. More comprehensively, employability is the capability to move self-sufficiently within the labor market to realize potential through sustainable employment. Yorke [46] defines it as “a set of achievements—skills, understandings and personal attributes—that makes graduates more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations, which benefits themselves, the workforce, the community and the economy”.

To measure the employability of graduates, researchers have developed employability measurement models and ways to develop these skills, abilities, and personality traits from different perspectives, such as those of the government, universities, and students [47,48]. For example, Hillage and Pollard [18] proposed the four main elements model, which consists of employability assets (a person’s knowledge, skills and attitudes), deployment (career management skills, including job search skills), presentation and job-obtaining skills (for example CV writing, work experience and interview techniques), personal circumstances (for example family responsibilities) and external factors (for example the current level of opportunity within the labor market). Knight and Yorke proposed the USEM model, which includes four correlated employability components, i.e., understanding, skills, efficiency beliefs, and metacognition, thus improving our understanding of the employability of graduates [48]. Rothwell [35] developed the Employability Scale for Undergraduate Graduates. Dacre Pool and Sewell [47] proposed the CareerEDGE model for graduates’ employability, which covers seven parts, i.e., degree subject knowledge, understanding and skills; generic skills; emotional intelligence; career development learning; experience (work and life experience); reflection and evaluation; self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem. Based on the above, they also developed a tool called the Employability Development Profile (EDP), which can be used by college graduates and their stakeholders (including parents, education workers, employers, and the government) for diagnosing the employability development level of graduates. This diagnostic tool is a self-reported questionnaire that asks respondents to rate different aspects of their employability as defined by the CareerEDGE model.

2.4. Research Hypotheses

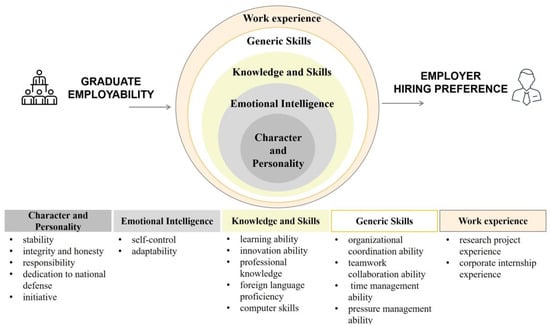

The above research results provide an important theoretical basis for this study. Despite the growing uncertainty in the labor market and the rapid obsolescence of knowledge [49], a number of studies have begun to consider employers’ perspectives to determine what HE should provide. For example, as Teichler [50] found, based on employers’ different traditions, political biases, and other factors, their perceptions of individuals with similar educational qualifications are changing. There are also many studies examining employers’ perceptions of the expected skills that an individual acquires from international educational experience [51]. However, no research has looked at the specificity of the national high-end equipment manufacturing, and it remains unclear what really matters to employers of national high-end equipment manufacturing in the hiring decision process. In this study, the actors are employers, defined as “those responsible for recruitment in employing organisations effectively acting as gatekeeper to the labor market” [51]. Their attitudes and selection preferences towards job seekers are crucial in the final recruitment decisions. Drawing on Yorke’s definition, this study examines national high-end equipment manufacturing employers’ perceptions of the graduates’ employability from national characteristics discipline programs, focusing primarily on the skills, understandings, and personal attributes acquired from national characteristics discipline programs of HE. Drawing on the CareerEDGE model, graduate competency researches, and other studies on employability, graduates’ employability in national characteristics discipline programs is designed to consist of “emotional intelligence” (includes two indicators, i.e., self-control and adaptability), “knowledge and skills” (includes five indicators, i.e., learning ability, innovation ability, professional knowledge, foreign language proficiency, and computer skills), “generic skills” (includes four indicators, i.e., organizational coordination ability, teamwork collaboration ability, time management ability, and pressure management ability), “work experience” (includes two indicators, i.e., research project experience and corporate internship experience), “character and personality” (includes five indicators, i.e., stability; integrity and honesty; responsibility; dedication to national strategic needs; and initiative).

To sum up, the indicator system of graduates’ employability is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The indicator system of graduates’ employability.

- (1)

- Emotional intelligence and hiring preference

Goleman [52] defined emotional intelligence (EI) as “the ability to recognize the feelings of ourselves and others, inspire ourselves, and better manage emotions in interpersonal relationships”. Specifically, EI includes the ability to accurately perceive emotions, obtain and generate emotions to aid thinking, understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and regulate emotions in a reflective way to promote emotional and intellectual growth [53]. Goleman emphasized the point that EI is one of the main personality traits people need in order to obtain and maintain jobs. Jaeger [54] argued that EI can be improved through teaching and learning in the higher education environment. Yorke and Knight [55] considered EI to be an important aspect of the employability of college students. Copper [56] indicated in his study that people with high EI will motivate themselves and others to achieve more, and, in contrast to people with low EI, those with high EI can gain more success in their careers, build stronger interpersonal relationships, and enjoy better health. Thus, we make the following assumption in this study.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Employers prefer to hire graduates with high emotional intelligence.

- (2)

- Knowledge and skills and hiring preference

Johnes [57] argued that subject knowledge and skills in specific subjects are of great importance for graduates to find jobs. By receiving higher education and studying specific subjects, graduates can obtain degrees and related professional qualifications that enable them to obtain better employment opportunities. Employers judge job applicants according to their knowledge, skills, and academic degrees, which are often the only quantitative criteria available to them [47]. Therefore, knowledge and skills are considered the core of the model of graduates’ employability and a core component of graduates’ employability. Thus, we make the following assumption in this study.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Employers prefer to hire graduates with a high level of knowledge and skills.

- (3)

- Generic skills and hiring preference

As pointed out by Bennett et al. [58], generic skills can support the learning of any subject and can be subtly transferred to a series of environments, such as higher education or the workplace. Generic skills are necessary for a variety of jobs and occupations owing to their high degree of transferability [59,60]. For this reason, generic skills are also referred to as “core skills”, “key skills”, and “transferrable skills”. Knight and Yorke noted that “employers expect graduates to master good generic skills, including imagination and creativity, adaptability and flexibility, willingness to learn, independence and autonomy at work, attention to detail, teamwork and cooperation, planning, coordination and organization, and the ability to work under pressure in addition to relevant subject knowledge and skills as well as understanding” [48]. Thus, we make the following assumption in this study.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Employers prefer to hire graduates with a high level of generic skills.

- (4)

- Work experience and hiring preference

Work experience is also important to employers. It can be used not only as a factor that differentiates applicants but also as a tool for measuring an individual’s post-employment performance [61]. In addition, employers believe that work experience can provide individuals with broader skills and “more extensive” life experience and help develop skills that are easily transferrable to the workplace [62,63]. This is because candidates with work experience seem to have greater levels of maturity than those who have only conducted research at college or in the academic context. As one employer said, “It takes 18 to 24 months for even the best graduates to gain enough ability. That is a huge expenditure for the company. And it takes a lot of time to recover the initial cost” [64]. Sear [65] considered the lack of practical experience of graduates as the reason for their failure in not being selected as candidates for employment upon graduation. Fliers [66] confirmed such a need for interaction with the workplace in their graduate market report, warning that “if more than half of the applicants have work experience, graduates without work experience will not find any jobs.” Thus, we make the following assumption in this study.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Employers prefer to hire graduates with work experience.

- (5)

- Character and personality and hiring preference

Hodges [64] proposed that abilities in the workplace are a combination of cognitive skills (technical knowledge, expertise, and ability) and personal or behavioral characteristics (principles, attitudes, values, and motivations) and represent a function of individual characteristics. Most employers are aware of how important the personal characteristics of graduates are. A recent review of the literature examining the generic skills necessary for graduates indicates that employers increasingly focus on personality rather than technical skills [60,67,68,69]. Many researchers consider personal qualities an important component of ability, as they constitute important traits and characteristics on which individuals may draw when performing tasks or taking actions in both familiar and unfamiliar situations [61,65,70] and have a significant impact on individuals’ success [71]. The IEB [70] survey confirmed that most employers consider employees’ social skills and character types to be more important than their degree qualifications (60% considered good degree qualifications very important) or IT skills (61% considered these very important). Spencer [72] suggested that if people with suitable personality traits can be hired initially, they will quickly acquire the relevant knowledge and skills necessary to realize their employers’ performance goals. Thus, we make the following assumption in this study.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Employers prefer to hire graduates with good character and personality.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

The effect of generic skills on employer hiring preference is greater as levels of character and personality increase.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

The effect of knowledge and skills on employer hiring preference is greater as levels of character and personality increase.

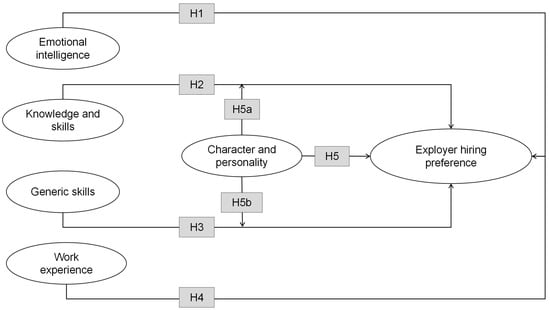

To sum up, the theoretical model of the impact of graduate employability on employer hiring preference is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The theoretical model of the impact of graduate employability on employer hiring preference.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

In this study, the electronic link and QR code of the questionnaire were distributed to 500 units in the recruiters’ database of the Student Employment Guidance Center (SEGC) of Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT) with hope and appreciation for feedback from at least 20 questionnaires. These 500 units are all from national high-end equipment manufacturing, such as aerospace, aviation, shipbuilding, weapons, nuclear industry, or electronic industry. The units participating in the survey include group companies, such as China Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), and their subordinate units, such as enterprises, scientific research institutes and other institutions—for example, Chinese Aeronautical Establishment (CAE) and its affiliated AVIC China Aero-polytechnology Establishment, which are all the subsidiaries of AVIC. This study also invites professors and students of the MSE to forward the questionnaire link and QR code to students in the same research group who are already employed in national high-end equipment manufacturing. In addition, as a subproject of this research, the corresponding author of this paper, as a leading teacher, led the students of the MSE to carry out the summer social practice named “entering enterprise”. The units visited were all from national high-end equipment manufacturing that have scientific research cooperation with MSE. In the process of visiting these units, the questionnaire was used as the outline, and interviews were also conducted with the human resources specialists of these units.

The respondents of the questionnaire were required to be human resource specialists, general technicians, department heads, or senior managers who participated in the recruitment process of fresh graduates. The questionnaire data is collected through the professional questionnaire platform whose website link is https://www.wjx.cn/ (accessed on 11 August 2021). The returned questionnaires with less than 1 min filling time or many missing items were excluded, which are considered to have not been filled in carefully, and the data is invalid.

In total, 927 copies of the questionnaire were recovered in this survey. The questionnaires were screened according to their completeness and the validity of the selected answers. Finally, 831 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective recovery rate of 89.64%. Among the interviewees, human resources specialists accounted for 33.57%; general technical personnel, 35.38%; department heads, 21.66%; and senior managers and others, 1.08%. In terms of educational background, bachelor’s degree holders represented 36.46% of respondents; master’s degree holders, 54.87%; and doctoral degree holders, 8.66%. Among the valid questionnaires, 64.26% were related to the aerospace industry; 33.57% to weapons; and 2.16% to aviation, electronic technology, and others. Among the valid questionnaires, state-owned enterprises accounted for 44.77% of responses; public institutions, 53.79%; and other types of organizations, 1.44%. In terms of organizational scale, organizations with 1000 to 3000 employees dominated, with a share of 48.38%; those with fewer than 1000 employees, 27.08%; and those with more than 3000 employees, 24.55%. In terms of the annual operating income of the organizations, most had an annual operating income of 100 million yuan or above (88.45%), and only 11.56% had an annual operating income of one million yuan (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characters.

3.2. Variable Measurement

The concept of employability: interpretation from an interactive perspective emerging first in North America, and then internationally since the end of the 1980s, can be seen as implying the importance of the role of employers and labor demand in determining a person’s employability [15,30]. Many studies exploring employers’ views on the relevance of capabilities to work focus mainly on the expected skills that individuals gain from their education, such as international education experience, graduates’ values, social awareness and generic intellectuality [73,74,75,76,77]. The United Nations (UN) has made employability one of four priorities for national youth employment policy action, along with entrepreneurship, equal opportunities between young men and women, and employment creation [30].

In this study, an Employability Scale for Graduates of National Characteristics Discipline Programs of Study (see Table 2) is designed by drawing on Yorke’s definition of graduate employability and CareerEDGE model in combination with the employment needs of China’s national high-end equipment manufacturing. In this table, “emotional intelligence” (EI) includes two indicators: self-control and adaptability. “Knowledge and skills” includes five indicators, i.e., learning ability, innovation ability, professional knowledge, foreign language proficiency, and computer skills. “Generic skills” includes four indicators, i.e., organizational coordination ability, teamwork collaboration ability, time management ability, and pressure management ability. “Work experience” includes two indicators, i.e., research project experience and corporate internship experience. “Character and personality” includes five indicators, i.e., stability; integrity and honesty; responsibility; dedication to national strategic needs; and initiative. To control for the impact of common variance, the question items measuring each latent variable were arranged randomly at the questionnaire design stage.

It is suggested in the strategic human resource management literature that an organization’s ability to achieve its strategic goals depends on its level of human capital (i.e., the abilities and characteristics of its employees) [78,79]. An employer’s hiring decisions are determined by the value of potential employees relative to the employers’ strategic goals. Thus, an increasing number of employers are hunting for individuals with the ability to optimize their productivity and growth goals [80]. Employers are also willing to invest scarce resources first to attract, identify, develop, and retain high-potential employees, as these employees are more productive than non-high-potential employees and can provide the organization with consistently high returns [81]. Meanwhile, the career planning of college students can effectively enhance the career stability of newly employed college graduates and significantly reduce their turnover rate [82]. In addition, the heads of the relevant units of China’s high-end equipment manufacturing mentioned the following issues several times in interviews with them:

As a national strategic industry, the national high-end equipment manufacturing is the pillar of national security. Employees should regard the satisfaction of major national strategic needs as an important mission and integrate their personal ideals and values into the national science and technology cause.

Therefore, this study adopts four indicators, i.e., national strategic awareness, motivation of accomplishment, career planning, and growth potential, as measurement indicators of employers’ hiring preferences in the national high-end equipment manufacturing.

Table 2.

Measure items in the questionnaire.

Table 2.

Measure items in the questionnaire.

| Construct | Source |

|---|---|

| Emotional intelligence | |

| Q1.Able to manage self emotions effectively | Dacre Pool et al. (2014) [83] |

| Q2. Able to adapt easily to new situations | Dacre Pool et al. (2014) [83] |

| Knowledge and skills | |

| Q3. Able to learn new knowledge and skills required for the job | Vaatstra (2007) [84] |

| Q4. Always propose new ideas, new theories, new methods | Pérez Vázquez (2013) [85] Gómez et al. (2017) [86] |

| Q5. Have a good command of professional knowledge of subject | Van Loo (2004) [87] Tomlinson (2012) [77] Qenani et al. (2014) [88] |

| Q6. Have good command of English reading and writing, and familiar with professional terms | Archer (2008) [70] Ricolfe (2013) [89] |

| Q7. Familiar with professional software | Archer (2008) [70] Van Loo (2004) [87] |

| Generic skills | |

| Q8. Able to allocate resources while controlling, motivating and coordinating group processes to achieve organizational goals | Archer (2008) [70] Vaatstra (2007) [84] Ricolfe (2013) [89] Van Loo (2004) [87] |

| Q9. Able to cooperate well with other members to achieve team goals in a team | Archer (2008) [70] Vaatstra (2007) [84] Tomlinson (2012) [77] Qenani et al. (2014) [88] Delamare and Winterton (2005) [59] |

| Q10. Be able to use time flexibly and efficiently by planning ahead | Archer (2008) [70] Schulz (2010) [90] Villardón-Gallego et al. (2013) [91] |

| Q11. Able to eliminate or control stressors with certain strategies to get the job done | Houghton et al. (2012) [92] |

| Work experience | |

| Q12. Have scientific research project experience in school | Qenani et al. (2014) [88] |

| Q13. Have valuable internship experience in related enterprise | Archer (2008) [70] Kuntz (2012) [93] Kucel (2013) [94] Vaatstra (2007) [84] |

| Character s and personality | |

| Q14. Willing to stay with the organization for a long time | Mora et al. (2000) [95] |

| Q15. Have honesty and integrity to work with others | Archer (2008) [70] Moreau (2006) [96] |

| Q16. With a high sense of the responsibility for work | Tomlinson (2007) [97] Ricolfe (2013) [89] |

| Q17. Willing to dedicate to national strategic needs | Van Scotter (1996) [98] |

| Q18. Be initiatively, consciously and actively do work | Gómez et al. (2017) [86] Ricolfe (2013) [89] |

| Employer hiring preference | |

| Q19. We like employee who have a plan for their career. | Du Xingyan et al. (2021) [82] |

| Q20. We like employee who have strong national strategic awareness. | Bamberger (2014) [78] Zoogah (2010) [99] |

| Q21. We like employee who have great achievement motivation. | Bamberger (2014) [78] Zoogah (2010) [99] |

| Q22. We like employee who have plenty of potential for growth. | Collings (2009) [81] |

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Following the principle for judging the coefficient of internal consistency proposed by Nunnally [100], the coefficient of internal consistency for each latent variable in the original scale is above 0.700, and the coefficient of internal consistency for the overall scale is 0.938, showing the high reliability of the scale, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Internal consistency reliability coefficients of the original scale.

As the scale is still in the development and testing stage, 22 question items were subjected to exploratory factor analysis using principal component analysis and the maximum variance orthogonal rotation method. The calculated KMO value is 0.942, and the Bartlett sphericity test is significant, indicating that there are common factors among the measured items.

Using the item-by-item deletion method proposed by Wu Minglong [101], “if a common factor contains measured question items of different dimensions, the dimensions with more measured question items can be retained and the items that have the largest factor load will be deleted”, 11 questions were retained, and 4 factors were extracted. The KMO value is 0.890, the Bartlett sphericity test is significant, and the variance explained is 72.10%, as shown in Table 4. This means that there are common factors among the measured question items. The load of each measured question item is above 0.600 [102], indicating that it can effectively reflect its factor constructs. The common values of the last 11 question items range from 0.644 to 0.844, indicating that the influence of each measured variable on the common factor is very important. Finally, a four-factor structure of the employability of graduates of national characteristics discipline programs at colleges and universities that contains eleven question items was obtained, and the factors were separately named cooperative innovation ability (CIA), knowledge and skills (KS), stress management and adaptation (SMA), and character and personality (CP).

Table 4.

Exploratory factor analysis of scale.

According to Table 5, the coefficient of internal consistency of each factor (Cronbach’s α value) ranges between 0.707 and 0.809, and that of the overall scale is 0.882, indicating high reliability. As shown in this table, the average variance extraction (AVE) value of each variable ranges from 0.481 to 0.616, indicating good convergent validity. The AVE value of each variable is greater than the square value of the correlation coefficient among the variables, indicating relatively good discriminant validity [103].

Table 5.

Reliability test results and discriminant validity test results.

4.2. Structural Model Analysis

To reduce multicollinearity, the average of the continuous variables among the independent variables was centralized in this study, with the dependent variable being hiring preference. As shown in Table 6, the VIF values of the main variables upon centralization are all less than 5, indicating weak collinearity among the variables.

Table 6.

Multi-collinearity diagnosis results.

In this study, with the aid of the Mplus 8.3 software and through the adoption of the hierarchical regression analysis method, the control variables cooperative innovation ability, knowledge and skills, stress management and adaptation, and character and personality were introduced into the multivariate regression model step by step, and models M1, M2, and M3 were obtained (see Table 7). As known from model M3, the regression coefficient of cooperative innovation ability is 0.302 (p = 0.015), which is significant at the 5% confidence level. This indicates a significant positive effect of cooperative innovation ability on hiring preference. The regression coefficient of knowledge and skills is 0.466 (p = 0.000), which is significant at the 0.1% confidence level, indicating a significant positive effect of knowledge and skills on hiring preference. The regression coefficient for stress management and adaptation is 0.501 (p = 0.000), which is significant at the 0.1% confidence level. This indicates that stress management and adaptation has a significant positive effect on hiring preference. However, the regression coefficient of character and personality is −0.254 (p = 0.059), which is significant at the 10% confidence level, indicating a significant negative effect of character and personality on hiring preference. This means the variable character and personality, characterized by “stability” and “dedication to national strategic needs”, is negatively correlated with the variable hiring preference, which is characterized by “national strategic awareness”, “motivation of accomplishment”, “development potential”, and “career planning” in national high-end equipment manufacturing organizations.

Table 7.

Latent moderated structure model results.

4.3. Moderation Analysis: High vs. Low Personality

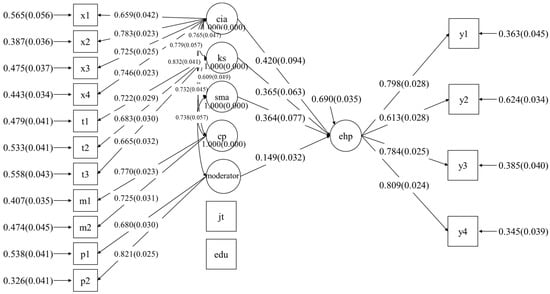

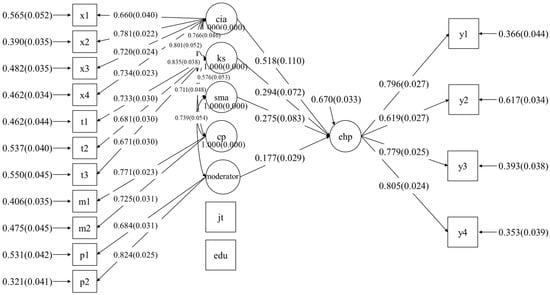

Based on M3, a latent moderated structure model (LMS) was adopted. The interaction items of the variables character and personality and cooperative innovation ability were introduced to obtain model M4, and those of the variables character and personality and knowledge and skills were introduced to obtain model M5. The moderating effect results are shown in Table 7.

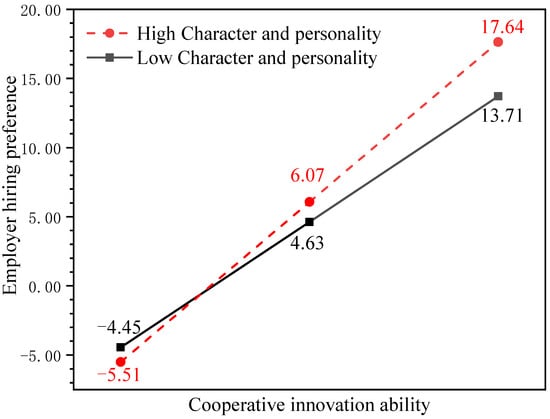

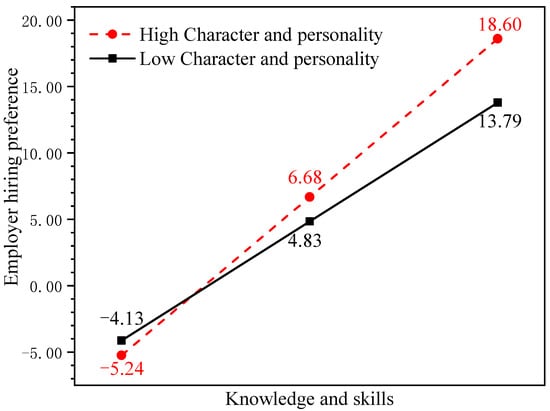

As known from model M4 and Figure 3, the variable cooperative innovation ability has a significant positive effect on employer hiring preference (β = 0.420, p = 0.000), but the effect of character and personality is not so significant (β = −0.112, p = 0.208). Meanwhile, the regression coefficient of the interaction items between character and personality and cooperative innovation ability is significant at the 1% confidence level (β = 0.149, p = 0.000). This indicates that character and personality has a significant positive moderating effect on the positive relationship between cooperative innovation ability and hiring preference. Similarly, according to model M5 and Figure 4, knowledge and skills has a significant positive effect on hiring preference (β = 0.294, p = 0.000), but the effect of character and personality is insignificant (β = −0.061, p = 0.486). Meanwhile, the regression coefficient of the interaction items between character and personality and knowledge and skills is significant (β = 0.177, p = 0.000) at the 1% confidence level. The results show that character and personality also has a significant positive moderating effect on the positive relationship between knowledge and skills and hiring preference (β = 0.177, p = 0.000).

Figure 3.

The latent moderated structure model results of Model 4 (show only significant).

Figure 4.

Latent moderated structure model results of Model 5 (show only significant).

To further analyze the strength of the moderating effect of character and personality, a diagram of the moderating effect of character and personality on cooperative innovation ability and hiring preference (see Figure 5) and a diagram of the moderating effect of character and personality on knowledge and skills as well as hiring preference (see Figure 6) were plotted, respectively, when the variable character and personality was one standard deviation above the mean and one standard deviation below the mean according to models M4 and M5. As shown in Figure 5, at a low level of character and personality, there is a weak relationship between cooperative innovation ability and hiring preference and only a slight increase in hiring preference with the level of cooperative innovation ability. At a high level of character and personality, the relationship between cooperative innovation ability and hiring preference is strong, and an increase in cooperative innovation ability effectively enhances the hiring preference of national high-end equipment manufacturing organizations. Similarly, as shown in Figure 6, the relationship between knowledge and skills and hiring preference is weak at a low level of character and personality and strong at a high level of character and personality.

Figure 5.

Moderating effect of character and personality on relationship between cooperative innovation ability and employer hiring preference.

Figure 6.

Moderating effect of character and personality on relationship between knowledge and skills and employer hiring preference.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the composition of the employability of graduates of national characteristics discipline programs of study and its effect on hiring preferences from an employer perspective. This study suggests that as long as national characteristics discipline programs at colleges and universities remain unclear about the employment needs or preferences of national high-end equipment manufacturing organizations and about the employment factors that will help graduates continue to gain employment in the national high-end equipment manufacturing, the conflicts between the supply and demand of personnel in the national high-end equipment manufacturing will remain severe, which will hinder the development of the national science and technology industry. To clarify these issues, a conceptual model was developed using a dataset of Chinese national high-end equipment manufacturing, and an empirical test was conducted. The main conclusions are as follows.

It was found through factor analysis that the employability of graduates of national characteristics discipline programs from an employer perspective can be represented by a four-factor structure that includes 11 question items. Among them, “innovative ability”, “organizational coordination ability”, “teamwork cooperation”, and “initiative” form the common factor I, which is named “cooperative innovation ability”; “professional knowledge”, “English proficiency”, and “computer skills” form the common factor II, which is named “knowledge and skills”; “adaptability” and “stress management ability” form the common factor III, which is named “stress management and adaptation”; “stability” and “dedication to national strategic needs” form the common factor IV, which is named “character and personality.”

It was discovered through main effect analysis that: (1) “Cooperative innovation ability” produces a significant positive effect on hiring preference, which is in line with the findings of Pérez Vázquez [85] and Gómez et al. [86] on innovative ability, the findings of Archer [70] and Vaatstra [84] on organizational coordination ability and teamwork cooperation, and the findings of Gómez et al. [86] and Ricolfe [89] on initiative. This indicates that the scientific and technological innovation personnel required by the national high-end equipment manufacturing do not seek to highlight their individual excellence but need to become integrated into the project team and bravely shoulder the burden of research and jointly tackle key problems in the team. (2) “Knowledge and skills” has a significant positive effect on hiring preference, which is consistent with the findings of Van Loo [87], Tomlinson [77], and Qenani et al. [88] on professional knowledge, the findings of Archer [70] and Ricolfe [89] on foreign language proficiency, and those of Archer [70] and Van Loo [87] on computer skills. This indicates that the national high-end equipment manufacturing attaches great importance to the professional skills, English proficiency, and professional software application skills of potential employees and emphasizes the professionalism, technical level, and internationalization of these employees.

(3) “Stress management and adaptability” has a significant positive effect on hiring preference, which is in line with the findings of Houghton et al. [92] on stress management and adaptability and those of on self-control. This indicates that for the national high-end equipment manufacturing, as a national strategic industry that supports the construction of the national modern industrial system and promotes scientific and technological advancement, as well as social and economic development, potential employees are required to have good stress management ability and response strategies and to be able to adapt to the working environment of the national high-end equipment manufacturing in view of the importance and arduousness of its historical mission and main tasks.

(4) “Character and personality” has a significant negative effect on hiring preference, which is not in line with the findings of Mora et al. [95] on stability and those of Van Scotter [98] on dedication. This may be mainly because “hiring preference”, which is characterized by “national strategic awareness”, “motivation of accomplishment”, “development potential”, and “career planning”, is negatively correlated with the variable “character and personality”, which is characterized by “stability” and “dedication to national strategic needs”. This suggests that the high-end equipment manufacturing will not just take into account employees’ low turnover intention and strong dedication to nation when hiring them.

The moderating effect analysis results indicate that “character and personality” significantly and positively moderates the positive relationship between “cooperative innovation ability” and hiring preference, as well as the positive relationship between “knowledge and skills” and hiring preference. The character and personality of potential employees have no direct effect on employers’ hiring preference, which means that the character and personality of potential employees do not act alone, but produce a significant moderating effect in a path where other elements of ability affect hiring preference. Thus, the characteristics and personalities of potential employers are also very important. When focusing on training students’ cooperative innovation ability, knowledge and skills, stress management and adaptability, national characteristics discipline at colleges and universities still need to strengthen the cultivation and guidance of students’ characters and personalities and increase their awareness of the importance of serving major national strategies and national security and their commitment to the mission of national science and technology innovation.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings show that employers of national high-end equipment manufacturing prefer graduates with higher levels of “cooperative innovation ability”, “knowledge and skills”, “stress management and adaptation” within Chinese national characteristics discipline programs, which is owing to the national high-end equipment manufacturing in view of the importance and arduousness of its historical mission and main tasks. Particularly, although national high-end equipment manufacturing has always emphasized employee loyalty and dedication, employers in national high-end equipment manufacturing will not just take into account employees’ low turnover intention and strong dedication to nation when hiring them. However, “character and personality” does not have a direct effect on employer hiring preference, but instead the effect of cooperative innovation ability and knowledge and skills are fully moderated by character and personality.

In view of the fact that the sample data for this study come mainly from the aerospace and weapons segments of national high-end equipment manufacturing in China (accounting for 97.83% in total) and the controlled and staged survey scope of the sample data, the research conclusions only reflect the current stage of development and have certain limitations. Future research may analyze the sample data of employers in the fields of aviation, electronic technology, shipbuilding, and the nuclear industry in China’s high-end equipment manufacturing and make a comparative analysis with the research results of this paper. Future research may also measure employability from the perspective of graduates or current students of national characteristics discipline and conduct a comparative analysis against the perspective of employers. In this way, the pertinence of the training and improvement of the employability of graduates of national characteristics discipline programs can be clarified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and S.L.; methodology, H.W. and S.L.; software, H.W. and S.L.; validation, S.L.; formal analysis, S.L. and P.Q.; investigation, H.W., S.L. and F.X.; resources, H.W.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W., S.L. and F.X.; writing—review and editing, H.W., S.L. and P.Q.; visualization, S.L. and P.Q.; project administration, F.X.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, funding number 7217020877, and Beijing Institute of Technology, funding number 2021ZXJG013.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Slotten, H.R. Humane chemistry or scientific barbarism? American responses to World War I poison gas, 1915–1930. J. Am. Hist. 1990, 77, 476–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Ling, C.; Xiuhai, D.; Tongyu, Y.; Bendong, W. Building a world-class university: The reference provided by AAU. Educ. Res. Tsinghua Univ. 2003, 24, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Sergi, B.J.; Tran, E.D.; Nek, R.; Howieson, S.V. Research Collaborations between Universities and Department of Defense Laboratories; IDA Science and Technology Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://military.cnr.cn/sdpl/201407/t20140716_515872753.html (accessed on 20 June 2014).

- Beale, M.; Street, T.; Wittams, J. Study War No More: Military Involvement in UK Universities. London: Campaign against Arms Trade, 2007. Available online: http://www.studywarnomore.org.uk/documents/studywarnomore.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2015).

- Bogart B Unwarranted Influence: Chronicling the Rise of US Government Dependence on Conflict, 2007. Available online: http://www.nwopc.org/files/PentaVersitiesByState.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2015).

- Schwager, M.; Rahn, L. An informal guide to key United States defence research agency funding for Australian researchers. In Education & Science Branch; Embassy of Australia: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Ministry of Defense. Defense programs and budget of Japan: Overview of FY2022 budget. In Defense; Japan Ministry of Defense: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.sciping.com/33068.html (accessed on 21 November 2019).

- Available online: http://www.81.cn/2017zt/2017-12/06/content_7857435.htm (accessed on 6 December 2017).

- Jianwei, Z.; Xingyu, X.; Haihong, L.; Yufan, Z. Developing Logic and Future Trend of National Defense Science & Technology Talents Cultivation System in Chinese Universities during the Past 70 Years of the Founding of the PR. China High. Educ. Res. 2019, 11, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Huimin, S. The State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense and the Ministry of Education Jointly Build 16 Colleges and Universities and 25 Local Colleges and Universities. Available online: http://www.sohu.com/a/101352629_232611 (accessed on 5 July 2016).

- Xiangqian, L.; De, Z.; Lin, L.; Lin, H. Research on the Training Mode of Collaborative Innovation of National Defense Technology Industry. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2018, 35, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, L.; Yong, L.; Haiyan, W. On Exploration and Practice of Training Mode Reform for Professional Degree Postgraduates in National Defence Industry—Based on Case Study of Personnel “Two-Way Extending” Training Patten in Northwest Polytechnical University. J. Grad. Educ. 2017, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gazier, B. Observations and recommendations. In Employability—Concepts and Policies; Gazier, B., Ed.; European Employment Observatory: Berlin, Germany, 1998; pp. 298–315. [Google Scholar]

- Gazier, B. Employability—Definitions and trends. In Employability: Concepts and Policies; Gazier, B., Ed.; European Employment Observatory: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gazier, B. Employability: The complexity of a policy notion. In Employability: From Theory to Practice; Weinert, P., Baukens, M., Bollerot, P., Eds.; Transaction Books: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hillage, J.; Pollard, E. Employability: Developing a framework for policy analysis. Labour Mark. Trends 1998, 107, 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, A.; Ferguson, J.; Gilmore, K. Issues concerning the employment and employability of disabled people in UK accounting firms: An analysis of the views of human resource managers as employment gatekeepers. Br. Account. Rev. 2007, 39, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department For Work and Pensions. The UK Employment Action Plan 2002; DWP (Department for Work and Pensions): London, UK, 2002.

- Department for Education and Employment. The Design of the New Deal for Long-term Unemployed People; Department for Education and Employment: London, UK, 1998.

- Department for Education and Employment. The UK Employment Action Plan; Department for Education and Employment: London, UK, 2001.

- International Labour Organization. Training for Employment: Social Inclusion, Productivity Report V; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Recommendations of the High Level Panel of the Youth Employment Network; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; McMahan, G.C.; McWilliams, A. Human resources and sustained competitive advantage: A resource-based perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1994, 5, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijde, C.M.V.D.; Van Der Heijden, B.I. A competence-based and multidimensional operationalization and measurement of employability. Hum. Resour. Manag. Publ. Coop. Sch. Bus. Adm. Univ. Mich. Alliance Soc. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 45, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dam, K. Antecedents and consequences of employability orientation. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 13, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, A.; Van Vianen, A.; Van der Heijden, B.; Van Dam, K.; Wellemsen, M. Understanding the factors that promote employability orientation: The impact of employability culture, career satisfaction, and role breadth self-efficacy. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuaid, R.W.; Lindsay, C. The Concept of Employability. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, G. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, 2nd ed.; National Bureau for Economic Research: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M. A theoretical model of on-the-job training with imperfect competition. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 1994, 46, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H.E. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century; Hachette UK: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson, E.; Marklund, S. The relationship between perceived employability and subsequent health. Work. Stress 2007, 21, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, A.; Herbert, I.; Rothwell, F. Self-perceived employability: Construction and initial validation of a scale for university students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J. A dispositional approach to employability: Development of a measure and test of implications for employee reactions to organizational change. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, S.; Waters, L.; Briscoe, J.P.; Hall, D.T.T. Employability during unemployment: Adaptability, career identity and human and social capital. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in human capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling, “Quarterly Journal of Economics. Consumer Misperceptions, Product Failure and Producer Liability.” Rev. Econonzic Stud. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The theory of screening, education, and the distribution of income. Am. Econ. Rev. 1975, 65, 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K.J. Higher education as a filter. J. Public Econ. 1973, 2, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, P. Universities and the knowledge economy. Minerva 2005, 43, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassard, J.; McCann, L.; Morris, J. Managing in the New Economy: Restructuring White-Collar Work in the USA, UK and Japan. In 21st Century Management: A Reference Handbook; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, P.T. Employability and quality. Qual. High. Educ. 2001, 7, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, M. Employability in Higher Education: What It Is-What It Is Not; Higher Education Academy York: York, UK, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pool, L.D.; Sewell, P. The key to employability: Developing a practical model of graduate employability. Educ. Train. 2007, 49, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knight, P.; Yorke, M. Learning, Curriculum and Employability in Higher Education; Routledgefalmer: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg, H.; Teichler, U. Higher Education and Graduate Employment in Europe: Results from Graduates Surveys from Twelve Countries; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Teichler, U. Higher Education and the World of Work: Conceptual Frameworks, Comparative Perspectives, Empirical Findings (Global Perspectives on Higher Education); Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y. Graduate employability: A conceptual framework for understanding employers’ perceptions. High. Educ. 2013, 65, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Working with Emotional Intelligence; Bantam Books: Nueva York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. Emotional Intelligence: Theory, Findings, and Implications. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, A.J. Job competencies and the curriculum: An inquiry into emotional intelligence in graduate professional education. Res. High. Educ. 2003, 44, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, P.T.; Yorke, M. Employability through the curriculum. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2002, 8, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R. Applying Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace. Train. Dev. 1997, 51, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Johnes, G. Career Interruptions and Labour Market Outcomes; Equal Opportunities Commission: Manchester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, N.; Dunne, E.; Carré, C. Patterns of core and generic skill provision in higher education. High. Educ. 1999, 37, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deist, F.D.L.; Winterton, J. What is competence? Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2005, 8, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasz, C. Do Employers Need the Skills They Want? Evidence from technical work. J. Educ. Work. 1997, 10, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Maxfield, T.; Gbadamosi, G. Using Part-time Working to Support Graduate Employment: Needs and Perceptions of Employers. Ind. High. Educ. 2015, 29, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisey, C.; Paisey, N.J. Developing skills via work placements in accounting: Student and employer views. Account. Forum 2010, 34, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juznic, P.; Pymm, B. Students on placement: A comparative study. New Libr. World 2011, 112, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hodges, D.; Burchell, N. Business Graduate Competencies: Employers’ Views on Importance and Performance. Asia-Pac. J. Coop. Educ. 2003, 4, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sear, L.; Scurry, T.; Swail, J.; Down, S. Graduate Recruitment to SMEs; Department for Business, Innovation and Skills: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fliers, H. The Graduate Market in 2014: Annual Review of Graduate Vacancies and Starting Salaries at Britain’s Leading Employers; High Fliers Research: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liston, C.B. Graduate Attributes Survey (GAS): Results of a pilot study. J. Inst. Res. Australas. 1998, 7, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Meade, P.; Andrews, R. Measuring employer satisfaction in higher education. Qual. Mag. 1995, 4, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, M. The Added Value of Undertaking Cooperative Education Year: The Measurement of Student Attributes; Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology: Melbourne, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, W.; Davison, J. Graduate Employability; The Council for Industry and Higher Education: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, D. Graduate Employability-Literature Review; LTSN Generic Centre: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, S.M. Competence at Work; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bremer, L. The Value of International Study Experience on the Labour Market the Case of Hungary: A Study on the Impact of Tempus on Hungarian Students and their Transition to Work. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 1998, 2, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.W. An exploration of the demand for study overseas from american students and employers. In A Report Prepared for the Institute of International Education; The German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD): Bonn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman, J.E.; Clarke, M. International experience and graduate employability: Stakeholder perceptions on the connection. High. Educ. 2010, 59, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, G.W.; Jolly, A. Graduate identity and employability. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 37, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomlinson, M. Graduate Employability: A Review of Conceptual and Empirical Themes. High. Educ. Policy 2012, 25, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, P.A.; Biron, M.; Meshoulam, I. Human Resource Strategy: Formulation, Implementation, and Impact; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N.; Chan, D.; Chan, E. Personnel Selection: A Theoretical Approach; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. The challenge of staffing a postindustrial workplace. In The Changing Nature of Performance: Implications for Staffing, Motivation, and Development; Ilgen, D.R., Pulakos, E.D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 295–324. [Google Scholar]

- Collings, D.G.; Mellahi, K. Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingyan, D.; Xiaozeng, W.; Suping, C. Influence of College Students’ Career Planning Education on Employment Stability: Taking the Survey Data of Mycos Graduates of a School as an Example. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 34, 134. [Google Scholar]

- Pool, L.D.; Qualter, P.; Sewell, P.J. Exploring the factor structure of the CareerEDGE employability development profile. Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaatstra, R.; Vries, R.D. The effect of the learning environment on competences and training for the workplace according to graduates. High. Educ. 2007, 53, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, P.J.P.; Lladosa, L.E.V. The Contribution of Higher Education to the Development of Innovation-Related Competences: A Graduates’ View//La Adquisición de Competencias para la Innovación Productiva en la Universidad Española; Ministerio de Educación: Córdoba, Spain, 2013.

- Gómez, M.; Aranda, E.; Santos, J. A competency model for higher education: An assessment based on placements. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 2195–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, J.; Semeijn, J. Defining and measuring competences: An application to graduate surveys. Qual. Quant. 2004, 38, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qenani, E.; Macdougall, N.; Sexton, C. An empirical study of self-perceived employability: Improving the prospects for student employment success in an uncertain environment. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricolfe, J.; Escriba-Perez, C. Analysis of the Perception of Generic Skills Acquired at University//Análisis de la Percepción de las Competencias Genéricas Adquiridas en la Universidad; Revista de Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 362, pp. 535–561.

- Schulz, M.; Roßnagel, C.S. Informal workplace learning: An exploration of age differences in learning competence. Learn. Instr. 2010, 20, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villardón-Gallego, L.; Yániz, C.; Achurra, C.; Iraurgi, I.; Aguilar, M.D.C. Learning Competence in University: Development and Structural Validation of a Scale to Measure//La competencia para aprender en la universidad: Desarrollo y validación de un instrumento de medida. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2013, 18, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Houghton, J.D.; Wu, J.; Godwin, J.L.; Neck, C.P.; Manz, C.C. Effective stress management: A model of emotional intelligence, self-leadership, and student stress coping. J. Manag. Educ. 2012, 36, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, A.M. Reconsidering the workplace: Faculty perceptions of their work and working environments. Stud. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucel, A.; Vilalta-Bufí, M. Why do tertiary education graduates regret their study program? A comparison between Spain and the Netherlands. High. Educ. 2013, 65, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.-G.; Garcia-Montalvo, J.; Garcia-Aracil, A. Higher education and graduate employment in Spain. Eur. J. Educ. 2000, 35, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.P.; Leathwood, C. Graduates’ employment and the discourse of employability: A critical analysis. J. Educ. Work. 2006, 19, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Graduate employability and student attitudes and orientations to the labour market. J. Educ. Work. 2007, 20, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scotter, J.R.; Motowidlo, S.J. Interpersonal facilitation and job dedication as separate facets of contextual performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoogah, D.B.; Abbey, A. Cross-cultural experience, strategic motivation and employer hiring preference: An exploratory study in an emerging economy. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2010, 10, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H.; Berge, J.M.F. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- MingLong, W. SPSS Statistical Application Practice: Questionnaire Analysis and Applied Statistics; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.S.; Dailey, R.; Lemus, D. The Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis and Principal Components Analysis in Communication Research. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjun, X.; Sen, L.; Xuanwei, Z. A study of the investor motivation of equity crowdfunding. Sci. Res. Manag. 2017, 38, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).