Abstract

Organizations are under mounting pressure to adapt to and to adopt corporate sustainability (CS) practices. Notwithstanding the increasing research attention given to the subject and the meaningful theoretical contributions, it is claimed that a definition, and a commonly accepted understanding of the concept of corporate sustainability, is still missing. Alignment on the meaning of CS is of critical importance for enabling coherent and effective practices. The lack of a sound theoretical foundation and of conceptual clarity of corporate sustainability has been identified as an important cause of unsatisfactory and fruitless actions by organizations. To address the questions “What is Corporate Sustainability?” and “Is it true there is a lack of convergence and clarity of the concept?”, we perform an ontological analysis of the different and interrelated concepts, and a necessary condition analysis on the key constitutive features of corporate sustainability within the academic literature. We demonstrate that the concept of corporate sustainability is clearer than most authors claim and can be well defined around its environmental, social and economic constitutive pillars with the purpose to provide equal opportunities to future generations.

1. Introduction

Corporate sustainability (CS) is the new paradigm for global business models. In order to determine success, an organization needs to give careful consideration to changes in the environmental and societal trends. Current understanding of the concept of corporate sustainability is regarded as too fragmented and aleatory to advance towards a coherent and homogeneous implementation of corporate sustainability practices in business activities [1]. General agreement exists regarding the primary importance of clarifying the concept of corporate sustainability for guiding the audience and enabling effective practices [2].

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of studies around the subjects of sustainability, corporate sustainability, sustainable development, ESG, CSR and other associated terminologies [3]. Similarly, there has been a proliferation of initiatives to address the subject, both from a reporting and implementation standpoint. The Global Reporting Initiative, the SASB Sustainability Accounting Standard Board, the Sustainable Development Goals, the COP 21, and the Zero Emissions target are only a few examples.

It is important to acknowledge that the subject has a wide scope and is complex in nature [4]. Moreover, it is revolutionary in its mission, as it challenges some of the core foundations of the capitalist system on which much of the world economy has been based during the last two hundred years. This is perhaps one of the root causes for the perceived and lasting confusion as to what corporate sustainability is and what it entails.

The primary objective of this research is to build the concept of corporate sustainability with the aim to bring clarity to its meaning and convergence for its definition. This is important for two major reasons. First, the concept is of global relevance, spans across economies and sectors, and theoretical guidance is necessary for aligning the efforts. Second, the lack of clarity of the concept leads to a variety of interpretations and this has been identified in the literature as a cause for ineffective and arbitrary practices. We believe the efforts detailed herein represent a substantial contribution to increasing the understanding of corporate sustainability, and in therefore aligning the view various stakeholders have, in enabling effective action within the corporate world, and directing future research focus.

To build the concept of corporate sustainability we use the guiding principles set forth by Gary Goertz [5]. In his book, Social Science Concepts and Measurement, Gary Goertz [5] extensively elaborates on how to build concepts in social science. He asserts that concepts are fundamentally about meaning, semantics and ontology. “They are theories about the fundamental constitutive elements of a phenomenon”. Goertz’s analysis draws from John Stuart Mill’s System of Logic [6], according to which: “To define, is to select from among all the properties of a thing, those which shall be understood to be designated and declared by its name; and the properties must be well known to us before we can be competent to determine which of them are fittest to be chosen for this purpose”; as well as from Aristoteles’s perspective on definitions, which advocates that good definitions give the sets of necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for a concept.

Although not directly linked to the guiding principles set forth by Goertz [5], a recent study by Meuer et al. [2] stands out for following a similar approach to building the concept of CS by identifying its constitutive elements. Based on an Aristotelian perspective of definitions, which proposes to reduce concepts to their essential attributes, Meuer et al. [2] identified 33 new definitions, from a systematic literature review between 1983 and 2018, and deconstructed the concept into its essential components: the genus as the family of objects to which corporate sustainability belongs; and three differentiae: the specificity of sustainable development, the level of ambition, and the level of integration. Together, these essential attributes allowed the authors to develop a conceptual space labelled the “corporate sustainability cube”, in which all definitions of corporate sustainability can be allocated and systematically compared. The remarkable contribution of Meuer et al. [2] has encountered three relevant limitations. First, it did not focus on the question of “what is” corporate sustainability. Instead, it provided a framework for analyzing and comparing definitions of corporate sustainability. Simply, the difficulty would be on how to assess the level of ambition and integration when the object of that ambition and integration “corporate sustainability” has not been qualified in its meaning, constituents, and highest extension [5]. Second, based on Aristoteles’s teaching that “a definition is a phrase signifying a thing’s essence” [7], they restricted the analysis to definitions only. However, concepts are not the same as definitions, and studying concepts by analyzing definitions is not correct [5]. A definition is a set of terms employed to refer to an object. They do not inform on the use of the concept nor lead to reflection. In this context, the analysis of the definitions of corporate sustainability described in academic and scientific publications is incomplete to study the “meaning” of the concept “sustainability” [8]. Third, the word-by-word coding approach of the definition is subject to interpretation and could be misleading when analyzed in isolation.

To overcome these limitations, our research extends on the work of Meuer et al. [2], and is based on the guiding principle by Gary Goertz [5] on how to construct social science concepts. It:

- Broadens the analysis to the meanings of corporate sustainability alongside their definitions,

- Performs an ontological analysis through a historical excursion into the evolution of corporate sustainability and its associated concepts, and

- Performs a necessary condition analysis to identify the constitutive components of the concept of corporate sustainability.

The results are aimed at answering the questions: “What is Corporate Sustainability?” and “Is it indeed true there is a lack of convergence and clarity over its concept?”. The objective is not to develop a novel concept of corporate sustainability, which would increase the multitude of interpretations and reinforce the existing issues, but to align the different perspectives to a commonly accepted understanding of the concept through the scientific rigor of the necessary condition analysis and the guiding principles of Gary Goertz, which are specifically tailored for building concepts in social science. Given the significance, the broadness and the transformational nature of the subject, both in businesses and societies, providing a unified theoretical underpinning is critical for enabling consistent practices within practitioners and for leading future research focus towards the areas of implementations and measurability of corporate sustainability. Concepts need to be clearly developed and properly defined to be able to be applied, implemented and measured.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the existing literature on the interpretations of the concept of CS and of the claimed lack of conceptual clarity, and associated consequences. Within this session, we provide an ontological analysis of corporate sustainability by means of an historical excursion as well as a review of the main identified themes around the conceptualization and evolution of CS. Section 3 explains the methodology for finding the constitutive features of CS through the necessary condition analysis outlined by Jan Dul [9]. Section 4 presents the results and discusses the findings; and Section 5 provides the conclusions.

2. Literature Review

In a study published by Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos [1], it was observed that a standardized definition of corporate sustainability does not exist. The study analyzed a variety of studies published on the subject, from 1995 to 2013, and concluded that the field of corporate sustainability is still evolving, and different approaches to define, theorize and measure it have been used. Similarly, Hahn et al. [10], highlighted the diversity of scholarly enquiry on corporate sustainability and concluded that given the complexity and diverse nature of corporate sustainability conceptual and definitional convergence is unlikely to happen. Confirming the variety of definitions and different understandings of corporate sustainability, Bergman et al. [11] identified three conceptual types of CS and nine sub-types. There is corporate sustainability in relation to corporate responsibility; meaning either identification, or distinction of the two concepts, or their causal interdependence. There are also mono-focal definitions of corporate sustainability; CS as moral leadership, or as corporate strategy. Finally, inclusive approaches to corporate sustainability: CS as a holistic concept, as part of the renowned Triple Bottom Line, as a financial incentive, or as an indexing exercise. In 2018, Frecè and Harder [12] analyzed that “Although a plethora of alternatives exists, companies often base their sustainability efforts more or less explicitly on the definition of the Brundtland Commission”. According to the Brundtland report—the first document that introduced the “sustainable development” concept [12]—businesses are said to have a crucial role in managing the impact of population in ecosystems, resources, food security, and sustainable economies in order to decrease the pressure society places on the environment (WCED), 1987. As reported by many authors [1,13,14,15,16], the origin of the corporate sustainability concept is often linked to the Brundtland report’s definition of “sustainable development” as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability for future generations to meet their own needs”. Despite the popularity of the Brundtland’s definition, its efficacy in giving practical guidance to organizations has often been questioned. Marshall and Brown [17] explained that even though it is the definition par excellence, it fails to provide any guidance for action. Banerjee et al. [18] asserted that it is rather a slogan that emphasizes development via a capitalist notion instead of undertaking a real eco-centric approach. Frecè and Harder [12] identified the inappropriateness of transposing the definition from a socio-political context to a corporate context, highlighting how this resulted in the lack of a sound theoretical foundation, which made the concept of corporate sustainability arbitrary. In 2022, Costa et al. conducted a literature review to integrate the different perspectives in order to broaden the understanding of the concept, on the premise that the diversity of research from the different fields has created confusion surrounding sustainability, corporate sustainability and corporate social responsibility [19].

The lack of a sound theoretical foundation and of conceptual clarity for corporate sustainability has been identified as the most important cause of unsatisfactory or ineffective actions by organizations for the betterment of society and the environment. Christen and Schmidt [20] have suggested that disagreement about the idea of sustainability results in the unsatisfactory situation that the sustainability idea is limited by arbitrariness and therefore loses its action guiding power. Through a meta-analysis of the different conceptions of sustainability, they concluded that arbitrariness is encountered on three different levels: in the designation of the subject field, in the characterization of sustainability science and consequently in providing a basis to assess policies. They provided a framework to structure an inclusive discourse on sustainability. Landrum [21] observed how everything business had done to this point would be classified as reducing unsustainability instead of creating sustainability. This inadequate approach, he argued, is primarily due to a restricted understanding of the meaning of corporate sustainability. Swarnapali [16] highlighted anecdotal evidence on how the lack of clarity over the meaning of corporate sustainability to researchers led to ambiguity in the CS field. On the same note, Salas-Zapata and Ortiz-Muñoz [8], indicated that lack of clarity entails problems for researchers since it can generate contradictory discourses which hinder operationalization and affect validity of the studies undertaken. Lack of clarity would also make it difficult to turn the discourse into decision-making actions, as well as interventions to reduce “unsustainability” [22]. Lankoski [23] identified business sustainability as an “essentially contested concept”, which hinders the achievement of a transition towards sustainability. He demonstrated how different conceptions resulted in different, at times incompatible, and yet legitimate interpretations of sustainability with significant consequences for management and outcomes. Meuer et al. [2] argued that the ambiguous impact of corporate sustainability relates to lack of clarity around the essence of CS. The lack of definitional clarity and the conflation of sustainability, corporate social responsibility, and similar terms give companies significant freedom to choose the sustainability items that best fit their corporate interests [13]. Until researchers can clearly differentiate between corporate sustainability from noncorporate sustainability practices, it will be difficult to evaluate whether firms are seriously embracing corporate sustainability objectives or simply engaging in greenwashing practices [24].

The consequences over the absence of conceptual clarity are well documented [2,8,13,16,22,23,24] and were made explicit at least ten years ago by Smith and Sharicz [25]: “The lack of clear definition means that there are no clear and unanimous guidelines of how companies should adopt sustainability”. Subsequently, there has been an effort in the research focus to clarify the different interpretations of corporate sustainability and to integrate the various viewpoints. However, given the complexity surrounding corporate sustainability, a variety of different approaches have been adopted. Some authors focused on defining corporate sustainability in the realm of strong sustainability versus weak sustainability (see page 10 for definitions of weak and strong sustainability), highlighting how economic activity should be bounded within environmental limits [21,26,27] or on grounding corporate sustainability in the different organizational theoretical foundations such as stakeholder theory (corporate players must look beyond profit making goals and seek positive results for all stakeholders), institutional theory (corporate players must incorporate the latest practices to increase legitimacy and survival prospects), or resource-based theory (corporate players must use resources in a way that improves effectiveness of achieving superior competitive advantage) [10]. Other authors focused on defining sustainability through an in-depth semantic and historical analysis of the different terminologies related to sustainability [28,29,30,31] or through the identification of the key elements necessary for integrating it into corporate practices [3,4,15,32,33].

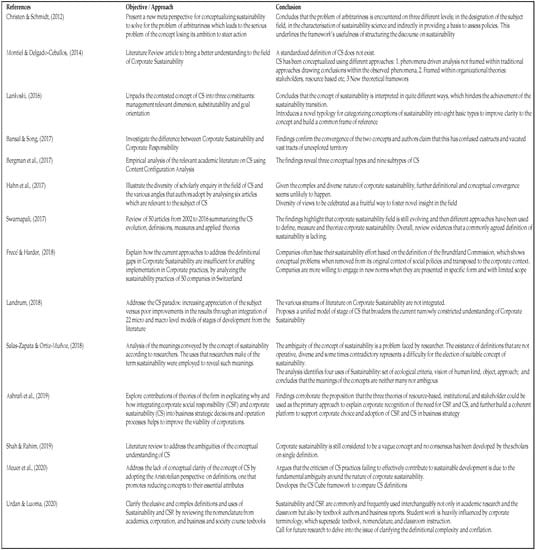

It is critical to observe that despite the proliferation of remarkable studies on the concept of corporate sustainability, conclusions remain that the concept is elusive and unclear. Jeremy Caradonna, the most read author on sustainability [14], sees this broadness as enriching the debate and offering different perspectives. However, trying to solve the conceptual issue by joining increasingly different debates and by creating own unique definitions unquestionably increases confusion [34]. There is rising clamor for bringing clarity to the concept of corporate sustainability to enable better understanding and consequently more reliable implementation [2,4,13]. See Figure 1 for different approaches for analyzing CS and conclusions.

Figure 1.

Overview of approaches for analyzing CS and conclusions.

2.1. Ontological Analysis of Corporate Sustainability

2.1.1. Sustainability, Sustainable Development and Corporate Sustainability

The literature on the conceptual history of “sustainability” is relatively small, but it shows a general agreement regarding its roots [14]. The origin of the sustainability discourse can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe, when economists started to write about the risks of forest depletion and the impact of population growth [35]. At the start of the 19th century, the protectionist and conservationist movement born in the United States, began to pay heed to the preservation of nature, as a result of the raise of romanticism, which brought attention to the appreciation of natural beauty [14]. It was only after the second world war that environmental considerations were regarded as necessary for the survival of society [36]. The book Silent Spring by Rachel Carson [37], documenting the damage of pesticides on the environment, is said to have kickstarted the post war environmentalist movement [14]. The new generation of environmental activists no longer viewed the world as divided into the two distinct domains of human and nature, but rather as deeply interconnected [38]. The report The Limits to Growth [39] issued by the Club of Rome—a elitist club made of leading global representatives—was acclaimed for its daring conclusions that if growth trends continued at the same pace, the limits to growth on the planet would be reached within one hundred years. The report analyzed the possibility to alter the growth trend and to establish conditions for ecological and economic stability that were “sustainable” further into the future and called for immediate action. The world “sustainability” was first used in 1972 in the context of man’s future in the British book Blueprint for Survival, and later used by the United Nations in 1978 in the context of “eco-development” [40]. It was the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED)’s Brundtland report titled Our Common Future, in 1987, which introduced the popularized term “sustainable development”. The WCED argued that economic development was necessary for improving human life and prosperity, but taxing on natural systems. The erosion of natural systems would ultimately undermine future economic and social development, as well as compromise opportunities for future generations [30].

The Brundtland report was cathartic in two ways. First, for the introduction of the concept of “sustainable development”; and second, for the introduction of social considerations in the concept of sustainability. The concept sustainable development was derived from different approaches. Some argued environmental responsibility was operationalized within companies to avoid sanctions related to environmental laws, and others argued the environmental responsibility responded to moral obligations [41]. The fundamental assumption of growth underlying economic development is challenged by sustainability scholars, who highlighted the natural limits. These scholars took issue with the predominance of financial performance and asked to consider the impact on the broader system [30]. The variety of interpretations of the concept is so wide that there were at least seventy different definitions of sustainable development by 1992 [42], which increased to over three hundred by 2007 [43]. This is perhaps due to the complexity of integrating social and environmental dimensions while still promoting economic development [14,31]. Tøllefsen et al. [14] analyzed how the concept of sustainable development has become a magic concept. Magic concepts outline common characteristics of certain buzzwords within public management and they all have four characteristics in common:

- Broadness: they have a large scope with multiple, overlapping and sometimes conflicting definitions;

- Normative Attractiveness: they have an overwhelmingly positive connotation—it is hard to be against them;

- Implication of Consensus: they deny or downplay the existence of conflicting interests; and

- Global Marketability: they are known and used by practitioners and academics [44].

Tøllefsen [14] argued that the Brundtland’s report was what made sustainability into a magic concept. While since its origin, the meaning of sustainability was monothematically associated with the environment, the Brundtland definitions included additional constituents such as social considerations and conflicting objectives such as “sustainable” and “development”. According to Rist [45], “The height of absurdity was reached when the Brundtland Commission tried to reconcile the contradictory requirements to be met in order to protect the environment and, at the same time, to ensure the pursuit of economic growth that was still considered a condition for general happiness” (p. 21). An overarching definition of sustainability remains elusive and context dependent [13]. One of the most commonly reported contradictions is the understanding of sustainability and sustainable development. Many authors [22,46,47,48] claim that the term is an oxymoron, since sustainable development is unsustainable from the perspective of economic growth [49]. An important contribution from Salas-Zapata and Ortiz-Muñoz [8] revealed, however, that when looking at the concept of sustainability from the perspective of its meaning, rather than uniquely from its definitions, the concept is less ambiguous and can be employed to refer to four aspects: a set of social and ecological guiding criteria for human action, a goal of human kind, an object—meaning referents or entity that exist and can be represented—and an approach of study. “Notwithstanding the many definitions of sustainable development and the ongoing discourse, the Brundtland Report has contributed to conceptualizing the concept and forcing it to the top of the agenda of the UN and other multilayer organizations” [31]. The second groundbreaking contribution was the inclusion of social considerations into the sustainability concept, which was previously exclusively associated with environmental connotations. The concept of social responsibility had been up to that point a distinct concept from sustainability, with different roots and interpretations.

An important extension of the concept of sustainable development is the concept of corporate sustainability. Corporate sustainability is understood as the transfer of the concept of sustainable development to the corporate level [50]. Many authors documented how the definition of corporate sustainability is adopted from the concept of sustainable development as the application of sustainable development at the corporate level, including the short-term and long-term economic, environmental, and social aspect [10,16,29,31,33,50,51,52]. In fact, one of the most cited definitions of corporate sustainability is from Dyllick and Hockerts [53], who transposed the definition of sustainable development from the Brundtland’s report to corporate and defined corporate sustainability as “meeting the need of a firm’s direct and indirect stakeholders, without compromising its ability to meet the needs of future stakeholders as well”. In this definition, the target audience changed from “future generations” to “stakeholders” to adapt to the corporate dimension. The importance of corporate sustainability has been underscored by the United Nations’ establishment of a global association of companies and NGOs that follow the universal principles of the UN Global Compact in their activities and strategic orientations (UN 2013: 4). These defined corporate sustainability as a concept that gives a company long-term value in financial, social, environmental, and ethical terms [31].

2.1.2. Corporate Social Responsibility

The origins of corporate social responsibility (CSR) are traced to the Great Depression, embedded in the concepts of philanthropy, social give back, code of conduct, community service, and corporate managers as public trustees [54]. In a series of articles published by Yale Law Review, Berle [55] stated that responsibility could be understood as “Corporate powers equals powers in trust” for shareholders. Dodd [56] replied by asking “for whom are corporate managers trustees”, and argued that managers were statesmen to use their power for the betterment of society [29]. Due to the difficulties of the Great Depression, CSR failed to gain traction until the fifties [57]. In 1953, with his book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, Howard Bowen marked the modern era of CSR [31]. By enquiring on how CSR can help business to reach the goal of social justice and economic prosperity beyond the benefits to shareholders, Bowen asserted the essential role of corporate world in the economy and in society. He highlighted how the decisions of businessmen have direct bearing on the quality of our lives. However, as individual businessmen represent only a small fraction of the economy, they fail to see how their actions relate to the broader economy. Nonetheless, if added together, the decisions of a businessman determine important matters such as the amount of employment and prosperity, the rate of economic progress, the distribution of income and the organization of industry and trade. Therefore, a businessman, by virtue of his strategic position and considerable decision-making power, is obligated to consider social consequences when making private decisions. They have social responsibilities that go beyond obligations to owners and shareholders [24]. A list of responsibilities of the businessman was proposed based on the need to take the social context into consideration at that time, and it included aspects such as: high standard of living, economic progress and stability, personal security, order and justice, freedom, development of the individual person, community improvement, national security and personal integrity. Some goals were found to be mutually conflicting, and this was addressed within the principle that businessmen should not disregard socially accepted values or place their own values above those of society [24]. In 1960, Davis developed the “Iron Law of Responsibility”, which held that the social responsibility of businessmen needs to be commensurate with their social power. As the concept continued to develop, it was also losing any clear meaning. Votaw [58] observed how the concept could convey different ideas of legal responsibility or liability, infer socially responsible behavior in an ethical sense, imply charitable contribution, or essentially be a synonym of legitimacy. In the late fifties, the concept started to attract criticism. Theodore Levitt stressed the risk of pursuing ambiguous corporate objectives and openly raised concern [31]. This criticism was later formalized by Milton Friedman in 1970. Friedman took the opposite view of Bowen [24], did not recognize the critical role of corporates in society and affirmed that the only responsibility of a corporate is to its shareholders. He highlighted the danger of distracting managers from profit making goals and of inappropriate potential misappropriation of shareholder’s money by executive managers in the name of CSR to advance their own social and political careers [31]. However, his mostly overlooked position is that ‘increasing profit’ may only be achieved by confirming to the basic rules of society, embodied in law and ethics [29]. As a counterargument, Edward Freeman stated that a corporate main responsibility is to its stakeholders, articulating how the inclusion of stakeholders, defined as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives”, in strategic management can mitigate corporate risk [59]. The eighties and nineties experienced a continued shift within the CSR literature, from a focus on ethics to a performance orientation and from a macro to a micro level application, such as at the corporate level [57]. The argument of positive linkage between stakeholder interests and CSR gained ground [60,61,62,63]; and most of the research that followed supported that CSR is in a business’s long-term self-interest: the so called “enlightened self-interest” to be socially responsible [64]. The concept of corporate social performance was introduced by Ackerman [31] to refer to the capacity of a corporate to respond to social pressure. Carroll [58] articulated “the pyramid of CSR” constituted by three components: an economic one, a legal one, and an ethical-philanthropic one. The economic component indicates that society expects corporations to make a profit and in the process of pursuing profit they are expected to abide by laws established by the society’s legal system. Ethical and discretionary philanthropic components suggest a responsibility that extends beyond meeting minimum legal requirements. As an extension of the pyramid of CSR, Wood [65] explained the dimensions of the CSP model and clearly included the environmental assessments in the company’s responsiveness to society. By the end of the nineties the inclusion of environmental aspects into CSR gained widespread recognition [31]. After the articulation of the concept sustainable development by the WCED’s report, sustainable development was explicitly linked to CSR with the introduction of the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), in 1998 by John Elkington. The TBL directed corporate responsibility put emphasis on the simultaneous pursuit of economic prosperity, environmental quality, and social equity. Consequently, CSR started more actively to embrace environmental aspects [31]. In the definition of CSR provided by the European Commission, CSR was seen as covering wider responsibilities beyond solely economic aims and business obligations, and these responsibilities were summarized as social and environmental obligations [66].

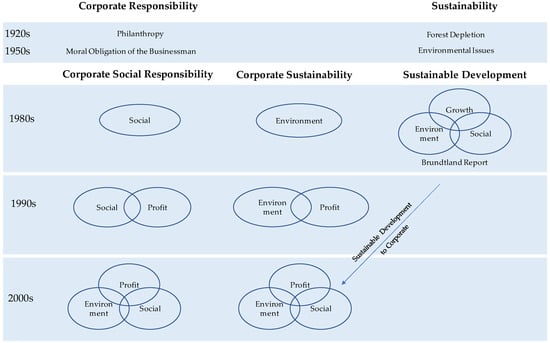

Although the concepts of responsibility and sustainability have different roots, responded to different needs and emerged at different times, they both shared a common interest in the relationship between business and society and spoke to the same audience [30]. See Figure 2 for evolution of the main concepts.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the main concepts.

2.1.3. Identified Themes around the Evolution of the Concept Corporate Sustainability

Through a critical reading of the recent literature on corporate sustainability, we observe the evolution of three major themes. First, proponents of convergence in the concept corporate sustainability to include multiple components, versus skeptical authors who argue convergence is not possible. Second, a divergent view of the role of corporates in the achievement of sustainable development as a primary actor versus that of an indirect contributor. Third, there is a continued debate over the sustainability dilemma.

On the topic of the convergence versus divergence of the different dimensions of corporate sustainability, two opposite views were taken by scholars. As the issues surrounding the concept of corporate sustainability are complex and far reaching, Amini and Bienstock [4] called for an integration of the variety of different perspectives in a multidimensional and comprehensive definition of corporate sustainability. Adopting a similar view, Christen and Schmidt [20] proposed an approach that sought to integrate the various viewpoints into an inclusive definition and explanatory framework of corporate sustainability. Costa et al. created a simplified framework that sought to integrate the different perspectives in order the broaden the understanding of Corporate Sustainability [19]. At the opposite end, based on a historical perspective, philosophical analysis and on the impact of changing context and values systems, according to Marrewijk, a one-solution fits all concept of corporate sustainability is not reasonable [67,68]. On the same note, Hahn et al. [10] analyzed six papers related to corporate sustainability and observed that the different angles that the authors adopted promised important contributions. However, they concluded that given the complexity and diverse nature of the concept of CS, further definitional and conceptual convergence seemed unlikely to happen. On the integration of the different elements of sustainability and responsibility in the concept of corporate sustainability Bansal and Song [30] offered a peculiar perspective. They took the position that convergence should not be celebrated as the blurring between responsibility and sustainability has “caused confusion and stunted growth in the field”. Nonetheless, their analysis showed conceptual converge of the two concepts in four dimensions: construct definition, ontological assumptions, nomological networks, and construct measurement. It seems that regardless of the philosophical discourse, actual convergence towards the integration of the different viewpoints and elements is already happening.

With reference to the second theme, in the same study of Bansal and Song [30], by answering the questions “what is a firm, how does it operate and who it responds to”, they observed how early responsibility researchers viewed a firm as a social actor among the various stakeholders, while early sustainability researchers saw firms as a system nested within other systems. The ontological position converged towards the end of the nineties so that both responsibility and sustainability researchers saw the firm as responsible to a broad range of demands and constituencies. Despite the claimed convergence, recent literature interprets the role of firms differently. Starting from the assumption that organizations cannot become sustainable, Frecè and Harder [12] argued that organizations simply contribute to the large system in which sustainability may or may not be achieved [69]. They propose a value-based definition of corporate sustainability that can act as a provider of guiding principles for sustainability policies to define activities that aim to “restitute and compensate”. Sheehy and Farneti [29] described how CSR refers exclusively to activities conducted by business organizations and the results from their operations, while sustainability may operate solely as a description without imposing any obligation on organizations. The extent of collaboration among social, political, and economic actors, together with the ambition of the vision and approach to integration, are said to differentiate between the weak and strong sustainability concept. O’Riordan [70] identified four worldviews of on environmentalism: Gaianism, Communalism, Accommodation, and Intervention. In the first two, humans are regarded as part of nature. In the second two, humans are in control of nature. Pearce [71] notes that these four worldviews correspond to the sustainable development literature positions known as weak and strong sustainability [72]. Weak sustainability requires production to remain intact so as to satisfy human wants [46]. In weak sustainability, humans control nature and have the ability to develop technological solutions to substitute natural capital by human made capital [73]. This a safe position that accommodates the environmental issues without renouncing economic growth and giving away power and control [70]. Strong sustainability instead, implies that economic activity is bound by environmental limits [74]. Within this view, human made capital cannot substitute natural resources, which must therefore be preserved and not utilized at a greater pace than they can be replaced [71]. The position of strong sustainability is more ambitious, values cooperation and views economic and social aspects strongly connected [70]. Strong and weak sustainability are criticized for failing to achieve sustainable development, as weak sustainability fails to conserve nature and strong sustainability fails to promote development [75]. Current corporate sustainability developments are framed around weak sustainability. This explains the lack of environmental progress despite the increasing focus on CS [21]. Corporate sustainability is focused on the business case and ignores larger global concerns, because business, not societal or ecological interests, define the parameters of sustainability [21]. This view reaffirms the critical role of corporate players in achieving sustainability. Even by adopting the best existing practices of the leading companies, the world would still be moving towards degradation [76]. This is due to a constricted view of corporate sustainability that focused on weak sustainability [75,77]. The debate over weak versus strong sustainability frames the premises over the theme of the sustainability dilemma. Many forms of development erode the environmental resources upon which they are based [20]. The dominant capitalist system has enabled humans to become somehow dominant over nature, while the future of humankind depends on preserving nature. The goals of continually maximizing profits and stimulating economic growth and consumption as a measure of prosperity and wellbeing implicitly declares human need and human created needs superior to all other things in the environment. Even intuitively, the opposite is true. The economic activity is intrinsically bound within the environmental limits. A livable planet is a precondition for humankind to continue to thrive. Within the environmental boundaries, we need a cohesive and inclusive society to organize production and consumption in order to ensure prosperity for the current and future generations [78]. The WCDE stated that the “environment does not exist as a separate sphere from human action, ambitions, and needs. The developmental and environmental crisis are apprehended as interlocking crises”. This view takes the social and the natural realm to be two interrelated systems [20]. The sustainability problem is well documented in the literature, but no attempts have been made yet to resolve them. If concepts and constructs are not defined clearly, scholars fail to build theory, communicate effectively and think creatively [79]. Further conceptual clarity is required.

3. Methodology

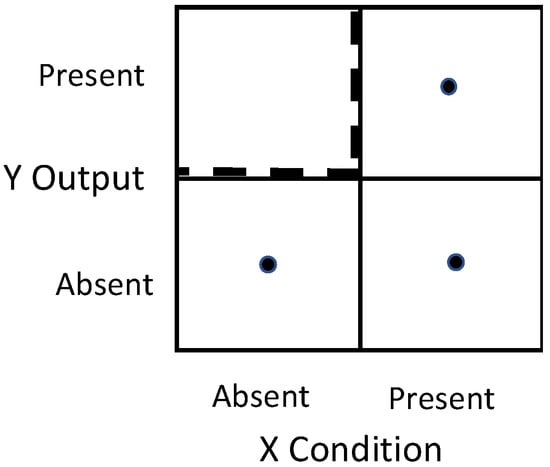

Concepts are an answer to the “what is” question and they are about meaning, semantic and ontology [5]. Developing valid concepts for social science involves analyzing descriptive, normative, and causal aspects, concurrently. To answer the “what is” question, one must identify the necessary and jointly sufficient conditions which constitute the defining features of the concept [5]. To look for the constitutive elements of the concept of corporate sustainability, we use the Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) methodology brought forward by Jan Dul [9], according to which, a condition is necessary when its absence results in the absence of the phenomenon. Therefore, the condition is necessary for the presence of the phenomenon. Such hypotheses are rarely formulated and tested in organizational sciences, and are different from conventional analysis where the complex interrelation of all factors attempts to explain the presence of the outcome in a probabilistic relationship. NCA ignores the causality that predicts the presence of the outcome with a large number of factors and only makes simple theoretical statements to predict the guaranteed absence of the outcome when the condition is absent [9]. The method is intuitive and straightforward, it triggers a new way of theoretical thinking that is based on necessity logic and it works in isolation from the rest of the causal structure, that is why it is necessary [9]. When searching the constitutive features, we are not concerned with the level of presence of the condition, but with whether the condition is present or not. Therefore, in the dichotomous interpretation of Dul’s [9] framework, the condition [X] and the outcome [Y] can assume only two values: absent or present. The contingency matrix, represented below, is a common way to present dichotomous necessary conditions [9]. The dashed lines are the ‘ceiling lines’ that separate the area with observations from the area without observations. For a condition to be necessary, the top left square requires to be empty, meaning there are no observations where the condition [X] is absent and the outcome [Y] is present, therefore the condition is necessary. Necessity does not equal sufficiency: the condition can be present, yet the outcome can be absent—bottom right square. The set of all necessary and jointly sufficient conditions constitute the concept [5]. See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Contingency Matrix.

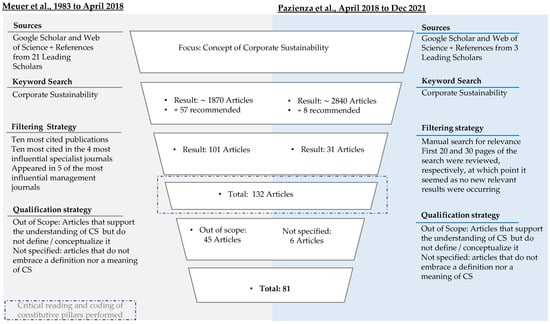

To build the hypothesis over the potential necessary conditions, we draw the data from the extensive systematic literature review performed by Meuer et al. [2] on corporate sustainability between 1983 and April 2018, which provides 101 articles. We extend the review until December 2021, with additional 31 articles for a total of 132 articles. See Figure 4. We adopted Meuer et al.’s [2] literature review, as they engaged in a similar mission of identifying the essential attributes of corporate sustainability with the aim to provide conceptual clarity. The purpose and the selection criteria of their articles are therefore pertinent and adherent to ours.

Figure 4.

Data search strategy and qualification criteria.

To identify the necessary conditions of the concept of Corporate Sustainability, we focused on the ‘What’ question [9], and prescind from the ‘How’ and ‘Why’ questions. In addition, as definitions, which in the context of CS can also be contested and conflicting, transcend the required analysis over meaning and context [5,73,80,81,82] to build complete concepts we analyze all 132 papers, even if they do not provide a definition. To this point, for example, one of the most cited definitions of corporate sustainability is from Dyllick and Hockerts [53]: “Corporate sustainability can be defined as meeting the needs of a firm’s direct and indirect stakeholders such as shareholders, employee, clients, pressure groups, communities, etc. without compromising its ability to meet the needs of future stakeholders as well” (p. 131). When reading the full article, the authors performed a considerable amount of analysis on the natural and social capital elements of corporate sustainability, which are not mentioned in the definition. Other examples include Sterman [83]: ‘Sustainability initiatives that are framed as also helping to heal the world’ (p.3), which does not provide any indication of what it takes to heal the world

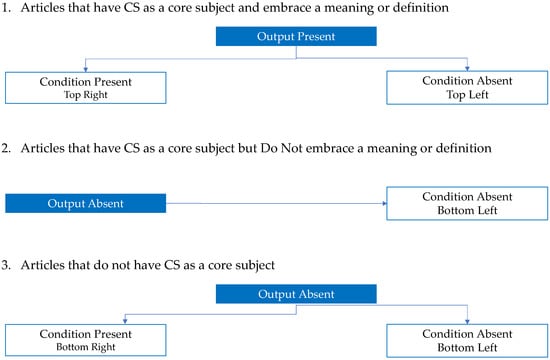

Dul [9] suggests two ways for testing or inducing necessary conditions with the data sets of observation. Either only successful cases—where the output is present—are purposely sampled and the omni-presence of the condition is an indication of necessity, or only cases with the absence of the condition are selected and the absence of the outcome is an indication of the necessity. Given the complexity and magnitude of the concept, we adopted the first approach, and built the following framework for guiding the allocation of papers into the contingency matrix—See Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Framework for allocating the articles in the contingency matrix.

Principle 1: Based on lessons drawn from the ontological analysis, we classified a paper as ‘present output’ when CSR, business sustainability, and other similar terminologies were used as to relate to the concept of the sustainability of a corporate, and treated it as ‘absent output’ when they meant to talk about some specific without a link to the concept of corporate sustainability. For example, Dahlsrud [84], Kleine [85], and Cheng [86], use CSR as the broader terminology for corporate sustainability, and they are treated as output present. Articles such as Delmas [87], Herva [88], and Ehrenfeld [89] that meant to talk specifically about the environmental aspects of a corporate with no reference to corporate sustainability are treated as output absent. Articles that are not specifically aimed at clarifying the concept of corporate sustainability are included as ‘present output’ when they clearly embrace a definition or a specific meaning of CS for their analysis.

Principle 2: Articles that have corporate sustainability in their discussion, but do not espouse any of the existing definition or meaning of CS are treated as ‘outcome absent’ and ‘condition absent’. This last point is necessary to allow for the reconciliation of the full number of the analyzed papers. We assume that something does not exist if its meaning is not defined or spelled out. For example, to explain corporate sustainability, Ahi [27,90], Urdan [13], and Swarnapali [16] mention a few definitions, but do not clarify which one of those will be used for their analysis, and they are therefore treated as output absent. Conversely, papers of Boiral [90] that speak of auditing practices in sustainability, or Figge [91] that talk about sustainability value added measurement, embrace a specific meaning of CS, and are treated as output present.

Principle 3: Articles that do not have CS as a core subject but are rather useful for its understanding are treated as output absent. See Figure 4 for qualification criteria.

When looking for the constitutive features, words with similar meaning are coded within their macro, most used, terminology. For example, ecology and nature are coded within environment, profit and organizational objectives are coded within economic, and organizational culture is coded within governance.

We performed three rounds of reviews and coding, through repeated critical reading, to confirm the findings and to ensure consistency with the guidelines. The third round was performed after confirming the validity of the scoping and allocation with Professor Jan Dul.

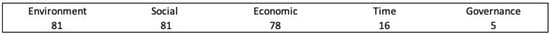

Based on the ontological analysis of the concepts of CS as well as on the frequency of the constitutive features cited in the literature, we formulate the hypothesis as follows: Constitutive features of CS may have Environmental, Social, Economic, Governance and Time dimensions.

The environmental dimension refers to the preservation of natural resources: when the production system utilizes more energy and materials that can be reproduced and when more emissions are emitted that can be absorbed, the industrial system becomes ecologically unsustainable [92]. The social dimension refers to the corporate responsibility to achieve a balance between a firm’s economic operations and the society’s aspiration and requirements for community welfare: social responsibility occurs when business firms, through the decisions and policies of its executive leaders, consciously and deliberately act to enhance the social well-being of those whose lives are affected by the firm’s economic operations [54]. The Economic dimension refers to the viability of a company from profitability standpoint: “Economically sustainable companies guarantee at any time cashflow sufficient to ensure liquidity while producing a persistent above average return to their shareholders” [53]. The Governance dimension refers to the arrangements a company needs to establish in order to guarantee the integrity of the organization as well as the integrity of internal management processes [93]. The Time dimension refers to the ability of firms to respond to short-term financial needs without compromising theirs, or others, ability to meet their future needs [94].

4. Results & Discussion

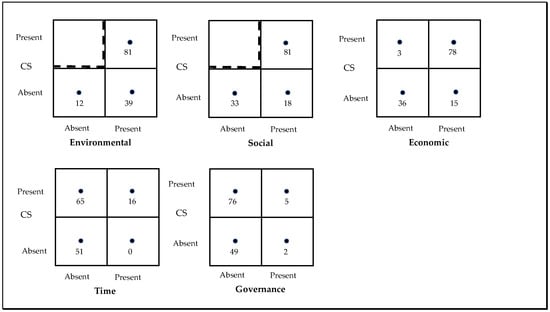

Based on the pre-established guidelines, 81 papers qualify as output present for espousing a definition or embracing a meaning of corporate sustainability. See Figure 4 and Figure 5. This is explained by the fact that the selected 132 papers also included articles there were simply instrumental for understanding the concept of corporate sustainability and did not necessarily express a definition or interpretation of corporate sustainability. Within these 81 papers, the dimensions of Environmental and Social are always present. This makes Environment and Social considerations necessary conditions, and therefore constitutive features of the concept of corporate sustainability. There are three papers where the outcome of CS is present and the aspect of ‘Economic’ was not explicitly mentioned as a constitutive feature. Additionally, the findings show that Time and Governance are not necessary conditions of the concept of CS, as, respectively, 65 and 76 papers define corporate sustainability without consideration to the Time and Governance dimensions. See Figure 6 for results.

Figure 6.

Number of articles that mention a specific pillar as constitutive to the concept of CS.

Contingency matrixes are presented in Figure 7. Since we adopted the approach of selecting and analyzing cases with positive outputs, the bottom part of the contingency matrix is theoretically not relevant. Nonetheless, we report the findings for completeness of information. The list of the 132 papers with reference to the identified constitutive features can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 7.

Contingency matrixes outputs.

That the environmental dimension of the concept of corporate sustainability is a necessary condition is perhaps of no surprise. As observed in the historical evolution, the concept was clearly born out of environmental considerations, and consistently carries this dimension through until today. It is of interest, however, to observe how the social dimension, which is typical of the concept corporate social responsibility, has become a necessary condition of corporate sustainability, cementing the convergence of the concepts of responsibility and sustainability. Based on the findings, to be sustainable, corporates need to jointly consider environmental and social issues. The results over the Economic dimension need deeper consideration. It cannot be disregarded that 78 out of 81 papers regard Economic as a necessary condition. The famous three pillars of the Triple Bottom Line are very well known to include the Economic dimension. The Brundtland report, which launched the concept of sustainable development, put economic development at the core of the concept. The absence of Economics in a limited number of articles can be explained by a few factors. With the foundation of the Global Reporting Index, an international organization that promotes standardization of sustainability reporting, the ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) approach was developed. The GRI took it as a given that companies need to be financially viable if they want to survive, and for this reason replaced the Economic dimension with the Governance dimension [93]. Since then, it has become popular within some corporates to report corporate sustainability in terms of ESG, especially after the support received by the UN “Principles for Responsible Investment”, whose members voluntarily commit to consider ESG criteria in their investment decision and to align the reporting practice accordingly. Nonetheless, the GRI themselves include Economic guidelines in their universal standard for reporting corporate sustainability (GRI 201 to GRI 207), confirming the centrality of this dimension in the concept of corporate sustainability. Furthermore, we argue that some authors focused on defining the ‘sustainability’ aspect of CS taking the Economic one as a given attribute of the definition of corporate operations. Specifically, the papers that do not mention Economic as a constitutive features of CS are: Kim and Lyon [95] who used ESG; Griffiths and Petrick [96], who investigated which organizational architectures can best facilitate the implementation of ecological and human sustainability, concerning with the new aspects of sustainability; and Cheng [86], who reported the definition of the European Commission, (2001) in the Green Report: “voluntary integration of social and environmental concerns in the companies’ operations and in the interaction with stakeholders” (p. 2). The same report, however, clearly cites in multiple parts of the document the centrality of the Economic dimension. The same definition is, in fact, reported by Van Marrewijk [68] with extensive analysis and inclusion of the Economic dimension.

In the literature, the Economic dimension has been defined/treated within three connotations: 1. The need to be profitable, 2. The need to reduce short term maximization of profits for the benefit of longer-term benefits, and 3. The impact of the Economic dimension on the Environmental and Social ones. The need to be profitable is intrinsic in the concept of a corporate entity—without sustained profits—a company ceases to exist. If a company ceases to exist, there are no longer Environmental and Social considerations associated to a corporate. The need to reduce short term profit maximization for longer term benefits and durability is at the very core of the Brundtland definition that started the concept of sustainable development, where environmental and social needs were counterposed to the need of guaranteeing human wellbeing through economic growth, both for the current and future generations. This states the centrality of the Economic dimension. On this note, it is important to clarify that within the concept of Corporate Sustainability, the Economic dimension is not and should not be associated with the traditional connotation of profit maximization, but with the notion of sustained profitability, which enables organizations to survive in the future. The third understanding relates to the sustainability dilemma, which indicates the unfound equilibrium between conflicting goals of economic growth with environmental and social preservation. Without the goal of profitability, environmental and social preservation become easier tasks. However, if without profitability the company ceases to exist and there is no longer damage done to the environment and society, therefore the Environmental and Social dimensions from a corporate standpoint are no longer applicable. In addition, equally to traditional statistical analysis where there is a tolerance for a 5% deviation, NCA allows for explainable outliers. Our deviation falls within the usual 5% level. In view of the explainable outliers and based on the normative analysis of the Economic dimension, we judiciously include the Economic dimension within the set of necessary conditions.

The dimension of Governance and Time clearly do not appear as a constitutive feature of corporate sustainability, and the respective hypothesis are therefore rejected. In fact, we argue that, although some authors specifically indicated them as foundational to the concept, Governance pertains to the realm of ‘How’ to implement corporate sustainability and Time pertains to the realm of ‘Why’ it is convenient or necessary to implement CS practices. Governance is a set of rules, practices, and processes, used to direct and manage a company. Governance is one of the organizational tools that can be used for enabling the implementation of CS practices, and it is an enabler rather than an end goal. The Time dimension explains the need to sustain the economic results, environmental protection, and social responsibility, as further as possible in the future. It responds to the question ‘why’ by clearly spelling out the importance of retaining the capability of satisfying the needs of the future generation: we need to implement CS practices to give future generations access to the same benefits as ours. It has been referenced in some of the articles as “leading a desirable future state for all stakeholders” [97], “intergenerational fairness” [75], “protecting, sustaining, and enhancing the human and natural resources that will be needed in the future” [52], and “resources must be distributed at macro levels across time” [94]. The Time dimension offers the purpose of corporate sustainability. Arguably the generally limited emphasis in the literature on the Time dimension, not necessarily as a constitutive feature, can be interpreted as one of the root causes of the CS business paradigm not living up to its promises. Losing sight of the purpose and therefore of the reasons whereby transformation is needed can cause delays and complacency with the status-quo.

What Is Corporate Sustainability?

Based on the ontological and NCA analysis, it is acceptable to conclude that the concept of corporate sustainability is made of the Environmental, Social and Economic pillars and that corporate sustainability is a new business paradigm that requires attention to Environmental, Social and Economic dimensions to be able to provide for current and future generations. We claim, the presence of the identified constitutive pillars are not only necessary but also jointly sufficient on the basis that no other constitutive pillars were found in the analysis of the academic literature of the last 30+ years. Furthermore, the necessity of the identified conditions implies no substitutability between them. This means that, greater attention to one dimension cannot compensate for the absence another. Each one of the three determinants must be in place, as there is no additive causality that can compensate for the absence of a necessary cause. Necessary causality is expressed as a multiplicative phenomenon [5]. CS = Environment × Social × Economic. If one dimension goes to zero, CS becomes zero, and it is therefore absent.

Based on this finding, we can observe that when we look at the defining feature of corporate sustainability: the ‘What’; and transcend from the ‘How’ and ‘Why’, the concept of corporate sustainability is not controversial, nor unclear, but rather well defined over the three pillars of Economic, Environmental and Social dimensions. Establishing this clarity over the concept of corporate sustainability is extremely important as the alleged absence of common understanding of what CS is, has been indicated as hindering its implementation and its measurability. Although the results may seem trivial, they address the continued claim of lack of clarity over the concept of corporate sustainability and call for researchers to find alignment towards what has already been achieved: convergence on ‘What’ is corporate sustainability and focus future research on what it still is a source of confusion and contention which is ‘How’ to integrate corporate sustainability and perhaps ‘Why’. The “How” is particularly problematic, as it requires a paradigm shift of the way managers conduct and conceive business, of the way corporate players are organized and perform, of the way results are understood and reported, as well as analysis is conducted over the unresolved issues regarding trade-offs between its elements. Starting from the now clearly defined concept of corporate sustainability research should focus on ‘How’ to implement and how to measure it to facilitate its integration into business practices. Possible observation over the lack of novelty of the results, in fact, reinforces the argument that the convergence of the concept over its constitutive pillars is established.

5. Conclusions

Literature on corporate sustainability has increased considerably in the last two decades, confirming the importance of the concept as a paradigm shift in the way we conduct business and understand the relations between production, society and the environment. Despite the increasing contribution toward clarifying the concept of corporate sustainability, conclusions continue to be drawn that the concept is still elusive and unclear, and therefore open to interpretation in its applicability. We conducted an ontological analysis of the concepts of sustainability, corporate social responsibilities and corporate sustainability and showed how the concepts have converged to include the Environmental, Social and Economic dimensions. Furthermore, to look for the constitutive pillars of corporate sustainability, we performed a Necessary Condition Analysis, which looks at the constant presence of the condition (the constitutive element) in the presence of output (the concept). We built the hypothesis around the Environmental, Social, Economic, Governance and Time dimensions and demonstrated that the concept of corporate sustainability is clearly constructed around the Environmental, Social and Economic dimensions. We explained how the lack of clarity is rather related to the methodologies for integrating CS into company’s operations, of which Governance is an important enabler. We highlighted how the literature has lost sight of the Time dimension, which provides the purpose of CS and explains the reason and the urgency for systematically applying CS practices in the business world. To make corporate sustainability effective we do need to look at ‘Why CS is important’. This is not always been clearly or sufficiently specified in the literature and it is critical to achieve a system wide sustainability. We, therefore, defined corporate sustainability as the new business paradigm that requires attention to Environmental, Social and Economic dimensions to be able to provide for current and future generations. The utilization of the NCA methodology is new and brings a new theoretical foundation to the concept as well as scientific evidence over its constitutive features. We call for researchers to refrain from further developing novel interpretations of corporate sustainability, which would continue to increase confusion over the concept, and to focus on the area that require attention and additional contribution, which is how to implement corporate sustainability. The performed analysis is simple, the results straightforward, and the observed conclusions important. To further validate the findings, we suggest performing the analysis to include empirical practices along with the theoretical underpinning. Future research focus can also be on the meaning and definition of the environmental, social and economic pillars, as they are pluriform and multidimensional; as well as their measurability, which is a key enabler for integration and accountability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14137838/s1, Table S1: List of 132 articles with coding of corporate sustainability.

Author Contributions

M.P. developed the theoretical framework, proposed the methodology, gathered the data, conducted the analysis and wrote the original draft. M.d.J. helped to conceive the study, provided academic guidance and practical support, and helped with review and editing. D.S. provided strong and in-depth supervision from the inception of the research proposal to the submission of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data which have been utized are in the Supplemental Material. There are no additional data to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Montiel, I.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability: Are We There Yet? Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuer, J.; Koelbel, J.; Hoffmann, V.H. On the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Planelles, J.; Segarra-Oña, M.; Peiro-Signes, A. Building a Theoretical Framework for Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Bienstock, C.C. Corporate Sustainability: An Integrative Definition and Framework to Evaluate Corporate Practice and Guide Academic Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, G. Social Science Concepts and Measurement. Available online: https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691205465/social-science-concepts-and-measurement (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Mill, J.S. A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and Inductive; Originally Published in 1843; University Press of the Pacific: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2002; p. 622. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.; Nagel, E. An Introduction to Logic and Scientific Method. Nature 1935, 135, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Zapata, W.A.; Ortiz-Muñoz, S.M. Analysis of Meanings of the Concept of Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jan Dul—Necessary Condition Analysis—Erasmus Research Institute of Management—ERIM. Available online: https://www.erim.eur.nl/necessary-condition-analysis/personal-pages/jan-dul/ (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Editorial, G.; Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Alberto Aragón-Correa, J.; Sharma, S. Advancing Research on Corporate Sustainability: Off to Pastures New or Back to the Roots? Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.M.; Bergman, Z.; Berger, L. An Empirical Exploration, Typology, and Definition of Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frecè, J.T.; Harder, D.L. Organisations beyond Brundtland: A Definition of Corporate Sustainability Based on Corporate Values. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urdan, M.S.; Luoma, P. Designing Effective Sustainability Assignments: How and Why Definitions of Sustainability Impact Assignments and Learning Outcomes. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 44, 794–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tøllefsen, T. Sustainability as a “Magic Concept”. Available online: https://web.p.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=11308354&AN=150379838&h=7IRq6kCmpF%2fv8SOKgj5At%2f6SR1mu%2be4UPCLL6jTUoCsMZoj%2fBOfM3EerTJWIBIYjLhZsdKVAPYIez49hV5xj5A%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d11308354%26AN%3d150379838 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Kantabutra, S.; Ketprapakorn, N. Toward a Theory of Corporate Sustainability: A Theoretical Integration and Exploration. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnapali, R. Corporate Sustainability: A Literature Review. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317428267_Corporate_sustainability_A_Literature_review (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Pdxscholar, P.; Marshall, S.; Brown, D.; Marshall, R.; Brown, D. The Strategy of Sustainability: A Systems Perspective on Environmental Initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 46, 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.B. Who Sustains Whose Development? Sustainable Development and the Reinvention of Nature. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.J.; Curi, D.; Bandeira, A.M.; Ferreira, A.; Tomé, B.; Joaquim, C.; Santos, C.; Góis, C.; Meira, D.; Azevedo, G.; et al. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework of the Evolution and Interconnectedness of Corporate Sustainability Constructs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, M.; Schmidt, S. A Formal Framework for Conceptions of Sustainability—A Theoretical Contribution to the Discourse in Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, N.E. Stages of Corporate Sustainability: Integrating the Strong Sustainability Worldview. Organ. Environ. 2018, 31, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I.; Morioka, S.N.; Sznelwar, L.I. When Sustainable Development Risks Losing Its Meaning. Delimiting the Concept with a Comprehensive Literature Review and a Conceptual Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoski, L. Alternative Conceptions of Sustainability in a Business Context. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, 1st ed.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.A.C.; Sharicz, C. The Shift Needed for Sustainability. Learn. Organ. 2011, 18, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsalis, T.A.; Evangelinos, K.I. A Framework To Measure Corporate Sustainability Performance A Strong Sustainability-Based View of Firm. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C.; Jaber, M.Y. A Quantitative Approach for Assessing Sustainability Performance of Corporations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo Silvestre, W.; Antunes, P.; Leal Filho, W. The Corporate Sustainability Typology: Analysing Sustainability Drivers and Fostering Sustainability at Enterprises. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2018, 24, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheehy, B.; Farneti, F. Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability, Sustainable Development and Corporate Sustainability: What Is the Difference, and Does It Matter? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.C. Similar But Not the Same: Differentiating Corporate Sustainability from Corporate Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Magnan, G.M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Understanding the Conceptual Evolutionary Path and Theoretical Underpinnings of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schrippe, P.; Ribeiro, J.L.D. Preponderant Criteria for the Definition of Corporate Sustainability Based on Brazilian Sustainable Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Addressing Stakeholders and Better Contributing to Sustainability through Game Theory. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1514216/Addressing_Stakeholders_and_Better_Contributing_to_Sustainability_through_Game_Theory (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Farley, H.M.; Smith, Z.A. Sustainability: If It’s Everything, Is It Nothing? 2nd ed.; Series: Critical Issues in Global Politics; Abingdon; Oxon: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781351124928. [Google Scholar]

- Grober, U. Sustainability: A Cultural History; UIT Cambridge Ltd.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780857840462. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Squaring the Circle? Some Thoughts on the Idea of Sustainable Development. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Proposing a Definition and a Framework of Organisational Sustainability: A Review of Efforts and a Survey of Approaches to Change. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, E.W.; Greenberg, P. The US Environmental Movement of the 1960s and 1970s: Building Frameworks of Sustainability. In Routledge Handbook of the History of Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.; Club of Rome; Potomac Associates. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Potomac Associates: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; ISBN 0876639015. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, C.V. The Evolution of Sustainability. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 1992, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrushkiv, B.; Melnyk, L.; Palianytsia, V.; Sorokivska, O.; Sherstiuk, R. Prospects for Implementation of Corporate Environmental Responsibility Concept: The Eu Experience for Ukraine. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2020, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R. Silent Spring; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, P.; Everard, M.; Santillo, D.; Robèrt, K.H. Reclaiming the Definition of Sustainability (7 Pp). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2007, 14, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitt, C.; Hupe, P. Talking About Government. Publ. Cover. Public Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rist, G.D. As a buzzword. In Deconstructing Development Discourse Buzzwords and Fuzzwords, 21st ed.; Cornwall, A., Eade, D., Eds.; Oxfam GB: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E. Steady-State Economics versus Growthmania: A Critique of the Orthodox Conceptions of Growth, Wants, Scarcity, and Efficiency. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4603736 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Mebratu, D. Sustainability and Sustainable Development: Historical and Conceptual Review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1998, 18, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redclift, M. Sustainable Development (1987-2005): An Oxymoron Comes of Age. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarkar, S.; Searcy, C. Zeitgeist or Chameleon? A Quantitative Analysis of CSR Definitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblek, V.; Bach, M.P.; Meško, M.; Kresal, F. Corporate Social Responsibility and Challenges for Corporate Sustainability in First Part of the 21st Century. Cambio. Riv. Sulle Trasformazioni Soc. 2020, 10, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business: Introducing a Typology From Business-as-Usual to True Business Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steurer, R.; Langer, M.E.; Konrad, A.; Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, Stakeholders and Sustainable Development I: A Theoretical Exploration of Business–Society Relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. Corporation, Be Good!: The Story of Corporate Social Responsibility; Dog Ear Publishing: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2006; ISBN 1598581031. [Google Scholar]

- Berle, A.A. Corporate Powers as Powers in Trust. Harv. Law Rev. 1931, 44, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodd, E.M. For Whom Are Corporate Managers Trustees? Harv. Law Rev. 1932, 45, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, J.J.; Mahon, J.F. The Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Financial Performance Debate: Twenty-Five Years of Incomparable Research. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The Corporate Social Performance-Financial Performance Link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.R.; Adler, P.; Aldrich, H.; Andreasen, A.; Austin, J.; Behling, C.; Cohen, M.; Dolan, B.; Gentile, M.; et al. Misery Loves Companies: Rethinking Social Initiatives by Business. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. Enlightened Self-Interest and Corporate Philanthropy. In A New Rationale for Corporate Social Policy; Committee for Economic Development: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate Social Performance Revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Corporate Social Responsibility Main Issues; Oce for Ocial Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2002; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/committees/deve/20020122/com(2001)366_en.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.D.; Zandbergen, P.A. Ecologically Sustainable Organizations: An Institutional Approach. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 1015–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, T. The Challenge for Environmentalism. In New Models in Geography, 1st ed.; Peet, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Unwin Hyman: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.; Turner, R.K.; Riordan, T.O.; Atkinson, G. Blueprint 3: Measuring Sustainable Development; Earthscan: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 9781853831836. [Google Scholar]

- Roome, N.J. Looking Back, Thinking Forward: Distinguishing between Weak and Strong Sustainability. Oxf. Handb. Bus. Nat. Environ. 2012, 620–629. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, K.; Muraca, B.; Baatz, C. Strong Sustainability as a Frame for Sustainability Communication. In Sustainability Communication; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, W. Reconciling “Weak” and “Strong” Sustainability. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 1999, 26, 1120–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]